2016-04-13 Wed

■ #2543. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方 (2) [language_change][evolution][language_myth]

人々が言語変化をどう理解してきたか,その3種類の立場について「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) で紹介した.そこでも参照した Brinton and Arnovick より,"Attitudes Toward Linguistic Change" と題する節の一部を引用したい (20--21) .くだんの3つの立場が読みやすくまとめられている.

Attitudes Toward Linguistic Change

Jean Aitchison (2001) describes three typical views of language change: as slow deterioration from some perfect state: as slow evolution toward a more efficient state; or as neither progress nor decay. While all three views have at times been held, certainly the most prevalent perception among the general population is that change means deterioration.

Linguistic Corruption

To judge from many schoolteachers, authors of letters to editors, and lay writers on language (such as Edwin Newman or William Safire), language change is always bad. It is a matter of linguistic corruption: a language, as it changes, loses its beauty, its expressiveness, its fineness of distinction, even its grammar. According to this view, English has decayed from some state of purity, its golden age, such as the time when Shakespeare was writing, or Milton, or Pope. People may interpret change in the language as the result of ignorance, laziness, sloppiness, insensitivity, weakness, or perhaps willful rebellion on the part of speakers. Their criticism is couched in moralistic and often emotionally laden terms. For example, Jonathan Swift in 1712 asserted that 'our Language is extremely imperfect; that its daily Improvements are by no Means in Proportion to its daily Corruptions; that the Pretenders to polish and refine it, have chiefly multiplied Abuses and Absurdities; and that in many Instances, it offends against every Part of Grammar' (1957: 6). Such views have prompted critics to try to prevent the decline of the language, to defend it against change, and to admonish speakers to be more careful and vigilant.

Given the inevitability of linguistic change, attested to by the records of all known languages, why is this concept of deterioration so prevalent? One reason is our sense of nostalgia: we resist change of every kind, especially in a world that seems out of our control. As speakers of our language, we feel that we are the best judges of it, and furthermore that it is something that we, in a sense, possess and can control.

A second reason is a concern for linguistic purity. Language may be the most overt indicator of our ethnic and national identity; when we feel that these are threatened, often by external forces, we seek to defend them by protecting our language. Tenets of linguistic purity have not been influential in the history of the English language, which has quite freely accepted foreign elements into it and is now spoken by many different peoples throughout the world. But these feelings are never entirely absent. We see them, for example, in concerns about the Americanization of Canadian or of British English.

A third reason is social class prejudice. Standard English is the social dialect of the educated middle and upper-middle classes. To belong to these classes and to advance socially, one must speak this dialect. The standard is a means of excluding people from these classes and preserving social barriers. Deviations from the standard (which are non-standard or substandard) threaten the social structure. Fourth is a belief in the superiority of highly inflected languages such as Latin and Greek. The loss of inflections, which has characterized change in the English language, is therefore considered bad. A final reason for the belief that change equals deterioration stems from an admiration for the written form. Because written language is more fixed and unchanging than speech, we conclude that the spoken form in use today is fundamentally inferior.

Of the other typical views towards language change, the view that it represents a slow evolution toward some higher state finds expression in the work of nineteenth-century philologists, who saw language as an evolving organism. The Danish linguist Otto Jespersen, in his book Growth and Structure of the English Language (1982 [1905]), suggested that the increasingly analytic nature of English resulted in 'simplification' and hence 'improvement' to the language. Leith (1997: 260) also argues that the historical study of English was motivated by a desire to demonstrate a literary continuity from Old English to the present, resulting in the misleading impression that the language has steadily evolved and improved toward a standard variety worthy of literary expression. The third view, that language change represents the status quo, neither progress nor decay, where every simplification is balanced by some new complexity, underlies the work of historical linguistics in the twentieth century and forms the basis of our text.

第1の堕落観と第2の進歩観については,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]),「#1839. 言語の単純化とは何か」 ([2014-05-10-1]),「#2527. evolution の evolution (1)」 ([2016-03-28-1]) を参照.第3の科学的な立場については「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]),「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]),「#2525. 「言語は変化する,ただそれだけ」」 ([2016-03-26-1]),「#2513. Samuels の "linguistic evolution"」 ([2016-03-14-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

2016-04-03 Sun

■ #2533. 言語変化の "spaghetti junction" (2) [terminology][pidgin][creole][language_change][terminology][tok_pisin][cognitive_linguistics][communication][teleology][causation][origin_of_language][evolution][prediction_of_language_change][invisible_hand]

一昨日の記事 ([2016-04-01-1]) に引き続き,"spaghetti junction" について.今回は,この現象に関する Aitchison の1989年の論文を読んだので,要点をレポートする.

Aitchison は,パプアニューギニアで広く話される Tok Pisin の時制・相・法の体系が,当初は様々な手段の混成からなっていたが,時とともに一貫したものになってきた様子を観察し,これを "spaghetti junction" の効果によるものと論じた.Tok Pisin に見られるこのような体系の変化は,関連しない他のピジン語やクレオール語でも観察されており,この類似性を説明するのに2つの対立する考え方が提起されているという.1つは Bickerton などの理論言語学者が主張するように,文法に共時的な制約が働いており,言語変化は必然的にある種の体系に終結する,というものだ.この立場は,言語的制約がヒトの遺伝子に組み込まれていると想定するため,"bioprogram" 説と呼ばれる.もう1つの考え方は,言語,認知,コミュニケーションに関する様々な異なる過程が相互に作用した結果,最終的に似たような解決策が選ばれるというものだ.この立場が "spaghetti junction" である.Aitchison (152) は,この2つ目の見方を以下のように説明し,支持している.

This second approach regards a language at any particular point in time as if it were a spaghetti junction which allows a number of possible exit routes. Given certain recurring communicative requirements, and some fairly general assumptions about language, one can sometimes see why particular options are preferred, and others passed over. In this way, one can not only map out a number of preferred pathways for language, but might also find out that some apparent 'constraints' are simply low probability outcomes. 'No way out' signs on a spaghetti junction may be rare, but only a small proportion of possible exit routes might be selected.

Aitchison (169) は,この2つの立場の違いを様々な言い方で表現している."innate programming" に対する "probable rediscovery" であるとか,言語の変化の "prophylaxis" (予防)に対する "therapy" (治療)である等々(「予防」と「治療」については,「#1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考」 ([2014-09-27-1]) を参照).ただし,Aitchison は,両立場は相反するものというよりは,相補的かもしれないと考えているようだ.

"spaghetti junction" 説に立つのであれば,今後の言語変化研究の課題は,「選ばれやすい道筋」をいかに予測し,説明するかということになるだろう.Aitchison (170) は,論文を次のように締めくくっている.

A number of principles combined to account for the pathways taken, principles based jointly on general linguistic capabilities, cognitive abilities, and communicative needs. The route taken is therefore the result of the rediscovery of viable options, rather than the effect of an inevitable bioprogram. At the spaghetti junctions of language, few exits are truly closed. However, a number of converging factors lead speakers to take certain recurrent routes. An overall aim in future research, then, must be to predict and explain the preferred pathways of language evolution.

このような研究の成果は言語の発生と初期の発達にも新たな光を当ててくれるかもしれない.当初は様々な選択肢があったが,後に諸要因により「選ばれやすい道筋」が採用され,現代につながる言語の型ができたのではないかと.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Spaghetti Junctions and Recurrent Routes: Some Preferred Pathways in Language Evolution." Lingua 77 (1989): 151--71.

2016-03-31 Thu

■ #2530. evolution の evolution (4) [evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_change][language_myth][neogrammarian][saussure][chomsky][diachrony][generative_grammar][terminology]

過去3日間の記事 ([2016-03-28-1], [2016-03-29-1], [2016-03-30-1]) で,言語変化を扱う分野において "evolution" という用語がいかにとらえられてきたかを考えた.とりわけ,近年の言語学における "evolution" は,一度その用語に手垢がつき,半ば地下に潜ったあとに再び浮上してきた概念であることを確認した.この沈潜は1世紀以上続いていたといってよく,ここから1つの疑問が生じる.言語学者がダーウィンの革命的な思想の影響を受けたのは19世紀後半だが,なぜそのときに言語学は生物学の大変革に見合う規模の変革を経なかったのだろうか.なぜその100年以上も後の20世紀後半になってようやく "linguistic evolution" が提起され,評価されるようになったのだろうか.この間に言語学(者)には何が起こっていたのだろうか.

この問題について,Nerlich の論文をみつけて読んでみた.Nerlich はこの空白の時間の理由を,(1) 19世紀後半に Schleicher が進化論を誤解したこと,(2) 20世紀前半に Saussure の分析的,経験主義的な方針に立った共時的言語学が言語学の主流となったこと,(3) 20世紀半ばにかけて Bloomfield や Chomsky を始めとするアメリカ言語学が意味,多様性,話者を軽視してきたこと,の3点に帰している.

(1) について Nerlich (104) は, Schleicher はダーウィンの進化論を,持論である「言語の進歩と堕落」の理論的サポートとして利用としたために,本来の進化論の主要概念である "variation, selection and adaptation" を言語に適用せずに終えてしまったことが問題だったとしている.ダーウィン主義を標榜しながら,その実,ダーウィン以前の考え方から離れられていなかったのである.例えば,ダーウィンにとって生物の種の分類はあくまで2次的なものであり,主たる関心は変形の過程だったが,Schleicher は言語の分類にこだわっていたのだ.ダーウィン以前の個体発生の考え方とダーウィンの種の進化論とが混同されていたといってよいだろう.Schleicher は,ダーウィンを真に理解していなかったといえる.

(2) の段階は Saussure に代表される共時的言語学者が活躍するが,その時代に至るまでにも,Schleicher の言語有機体説は青年文法学派 (neogrammarian) 等により,おおいに批判されていた.しかし,その批判は,言語変化の研究への関心のために建設的に利用されることはなく,皮肉なことに,言語変化を扱う通時態という観点自体を脇に置いておき,共時態に関心を集中させる結果となった.また,langue への関心がもてはやされるようになると,parole に属する言語使用や話者の話題は取り上げられることがなくなった.言語は一様であるとの過程のもとで,言語変化とその前提となる多様性や変異の問題も等閑視された.

このような共時態重視の勢いは,(3) に至って絶頂を迎えた.分布主義の言語学や生成文法は意味という不安定な部門の研究を脇に置き,言語の一様性を前提とすることで成果を上げていった.

この (3) の時代を抜け出して,ようやく言語学者たちは使用,話者,意味,多様性,変異,そして変化という世界が,従来の枠の外側に広がっていることに気づいた.この「気づき」について,Nerlich (106--07) は次の一節でやや熱く紹介している.

Thus meaning, language change and language use became problems and were mainly discarded from the science of language for reasons of theoretical tidiness: meaning and change are rather messy phenomena. Hence autonomy, synchrony and homogeneity finally enclosed language in a kind of magic triangle that defended it against any sort of indeterminacy, fluctuation or change. But outside the static triangle, that ideal domain of structural and generative linguistics, lies the terra incognita of linguistic dynamics, where one can discover the main sources of linguistic change, contextuality, history and heterogeneity, fields of study that are slowly being rediscovered by post-Chomskyan and post-Saussurean linguists. This terra incognita is populated by a curious species, also recently discovered: the language user! S/he acts linguistically and non-linguistically in a heterogenous and ever-changing world, constantly trying to adapt the available linguistic means to her/his ever changing ends and communicative needs. In acting and interacting the speakers are the real vectors of linguistic evolution, and their choices must be studied if we are to understand the nature of language. It is not enough to stop at a static analysis of language as a product, organism or system. The study of evolutionary processes and procedures should help to overcome the sterility of the old dichotomies, such as those between langue/parole, competence/performance and even synchrony/diachrony.

このようにして20世紀後半から通時態への関心が戻り,変化といえばダーウィンの進化論だ,というわけで,進化論の言語への応用が再開したのである.いや,最初の Schleicher の試みが失敗だったとすれば,今初めて応用が始まったところといえるかもしれない.

・ Nerlich, Brigitte. "The Evolution of the Concept of 'Linguistic Evolution' in the 19th and 20th Century." Lingua 77 (1989): 101--12.

2016-03-30 Wed

■ #2529. evolution の evolution (3) [evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_change][teleology][invisible_hand][causation][language_myth][drift][exaptation][terminology]

2日間にわたる標題の記事 ([2016-03-28-1], [2016-03-29-1]) についての第3弾.今回は,evolution の第3の語義,現在の生物学で受け入れられている語義が,いかに言語変化論に応用されうるかについて考える.McMahon (334) より,改めて第3の語義を確認しておこう.

the development of a race, species or other group ...: the process by which through a series of changes or steps any living organism or group of organisms has acquired the morphological and physiological characters which distinguish it: the theory that the various types of animals and plants have their origin in other preexisting types, the distinguishable differences being due to modifications in successive generations.

現在盛んになってきている言語における evolution の議論の最先端は,まさにこの語義での evolution を前提としている.これまでの2回の記事で見てきたように,19世紀から20世紀の後半にかけて,言語学における evolution という用語には手垢がついてしまった.言語学において,この用語はダーウィン以来の科学的な装いを示しながらも,特殊な価値観を帯びていることから否定的なレッテルを貼られてきた.しかし,それは生物(学)と言語(学)を安易に比較してきたがゆえであり,丁寧に両者の平行性と非平行性を整理すれば,有用な比喩であり続ける可能性は残る.その比較の際に拠って立つべき evolution とは,上記の語義の evolution である.定義には含まれていないが,生物進化の分野で広く受け入れられている mutation, variation, natural selection, adaptation などの用語・概念を,いかに言語変化に応用できるかが鍵である.

McMahon (334--40) は,生物(学)と言語(学)の(非)平行性についての考察を要領よくまとめている.互いの異同をよく理解した上であれば,(歴史)言語学が(歴史)生物学から学ぶべきことは非常に多く,むしろ今後期待のもてる領域であると主張している.McMahon (340) の締めくくりは次の通りだ.

[T]he Darwinian theory of biological evolution, with its interplay of mutation, variation and natural selection, has clear parallels in historical linguistics, and may be used to provide enlightening accounts of linguistic change. Having borrowed the core elements of evolutionary theory, we may then also explore novel concepts from biology, such as exaptation, and assess their relevance for linguistic change. Indeed, the establishment of parallels with historical biology may provide one of the most profitable future directions for historical linguistics.

生物(学)と言語(学)の(非)平行性の問題については「#807. 言語系統図と生物系統図の類似点と相違点」 ([2011-07-13-1]) も参照されたい.

2016-03-29 Tue

■ #2528. evolution の evolution (2) [evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_change][teleology][invisible_hand][causation][language_myth][drift][terminology]

昨日の記事 ([2016-03-28-1]) に引き続き,言語変化論における evolution の解釈について.今回は evolution の目的論 (teleology) 的な含意をもつ第2の語義,"A series of related changes in a certain direction" に注目したい.昨日扱った語義 (1) と今回の語義 (2) は言語変化の方向性を前提とする点において共通しているが,(1) が人類史レベルの壮大にして長期的な価値観を伴った方向性に関係するのに対して,(2) は価値観は廃するものの,言語変化には中期的には運命づけられた方向づけがあると主張する.

端的にいえば,目的論とは "effects precede (in time) their final causes" という発想である (qtd. in McMahon 325 from p. 312 of Lass, Roger. "Linguistic Orthogenesis? Scots Vowel Length and the English Length Conspiracy." Historical Linguistics. Volume 1: Syntax, Morphology, Internal and Comparative Reconstruction. Ed. John M. Anderson and Charles Jones. Amsterdam: North Holland, 1974. 311--43.) .通常,時間的に先立つ X が生じたから続いて Y が生じた,という因果関係で物事の説明をするが,目的論においては,後に Y が生じることができるよう先に X が生じる,と論じる.この2種類の説明は向きこそ正反対だが,いずれも1つの言語変化に対する説明として使えてしまうという点が重要である.例えば,ある言語のある段階で [mb], [md], [mg], [nb], [nd], [ng], [ŋb], [ŋd], [ŋg] の子音連続が許容されていたものが,後の段階では [mb], [nd], [ŋg] の3種しか許容されなくなったとする.通常の音声学的説明によれば「同器官性同化 (homorganic assimilation) が生じた」となるが,目的論的な説明を採用すると,「調音しやすくするために同器官性の子音連続となった」となる.

言語学史においては,様々な論者が目的論をとってきたし,それに反駁する論者も同じくらい現われてきた.例えば Jakobson は目的論者だったし,生成音韻論の言語観も目的論の色が濃い.一方,Bloomfield や Lass は,目的論の立場に公然と反対している.McMahon (330--31) も,目的論を「目的の目的論」 (teleology of purpose) と「機能の目的論」 (teleology of function) に分け,いずれにも問題点があることを論じ,目的論的な説明が施されてきた各々のケースについて非目的論的な説明も同時に可能であると反論した.McMahon の結論を引用して,この第2の意味の evolution の妥当性を再考する材料としたい.

There is a useful verdict of Not Proven in the Scottish courts, and this seems the best judgement on teleology. We cannot prove teleological explanations wrong (although this in itself may be an indictment, in a discipline where many regard potentially falsifiable hypotheses as the only valid ones), but nor can we prove them right; they rest on faith in predestination and the omniscient guiding hand. More pragmatically, alleged cases of teleology tend to have equally plausible alternative explanations, and there are valid arguments against the teleological position. Even the weaker teleology of function is flawed because of the numerous cases where it simply does not seem to be applicable. However, this rejection does not make the concept of conspiracy, synchronic or diachronic, any less intriguing, or the perception of directionality . . . any less real.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2016-03-28 Mon

■ #2527. evolution の evolution (1) [evolution][history_of_linguistics][language_change][teleology][language_myth][terminology]

生物学における用語 evolution の理解と同時に,言語学で使われてきた evolution という術語の意味がいかにして「進化」してきたかを把握することが肝心である.McMahon の第12章 "Linguistic evolution?" が,この問題を要領よく紹介している(この章については,「#2260. 言語進化論の課題」 ([2015-07-05-1]) でも触れているので参照).

McMahon は evolution には3つの語義が認められると述べている.以下はいずれも Web3 から取ってきた語義だが,1つ目は19世紀的なダーウィン以前の (pre-Darwinian) 語義,2つ目は目的論的な (teleological) 含意をもった語義,3つ目は現在の生物学上の語義を表す.

(1) Evolution 1 (McMahon 315)

a process of continuous change from a lower, simpler, or worse condition to a higher, more complex, or better state: progressive development.

(2) Evolution 2 (McMahon 325)

A series of related changes in a certain direction.

(3) Evolution 3 (McMahon 334)

the development of a race, species or other group ...: the process by which through a series of changes or steps any living organism or group of organisms has acquired the morphological and physiological characters which distinguish it: the theory that the various types of animals and plants have their origin in other preexisting types, the distinguishable differences being due to modifications in successive generations.

今回は,最も古い語義 (1) について考えてみたい.この意味での "evolution" は,ダーウィン以前の発想を含む前科学的な概念を表す.生物のそれぞれの種は,神による創造 (creation) ではなく,形質転換 (transformation) を経て発現してきたという近代的な考え方こそ採用しているが,その形質転換の向かう方向については,「進歩」や「堕落」といった人間社会の価値観を反映させたものを前提としている.これは19世紀の言語学界では普通だった考え方だが,ダーウィン自身は生物進化論においてそのような価値観を含めていない.つまり,当時の言語学者たち(のすべてではないが)はダーウィンの進化論を標榜しながらも,その言語への応用に際しては,進歩史観や堕落史観を色濃く反映させたのであり,その点ではダーウィン以前の言語変化観といってよい.

この意味での evolution を奉じた言語学者の代表選手といえば,August Schleicher (1821--68) である.Schleicher は Hegel (1770--1831) の影響を受け,人類は以下の順に発達してきたと考えた (McMahon 320) .

a. The physical evolution of man.

b. The evolution of language.

c. History.

人類は a → b → c と「進歩」してきたが,c の歴史時代に入ってしまうと,どん詰まりの段階であるから,新しいものは生み出されない.したがって,あとは「堕落」しかない,という考え方である.言語も含めて,現在はすべてが堕落の一途をたどっているというのが,Schleicher の思想だった.

価値の方向こそ180度異なるが,同じように価値観をこめて言語変化をみたのは Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) である.Jespersen は印欧語にべったり貼りついた立場から,屈折の単純化を人類言語の「進歩」と見た (see 「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]), 「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1])) .

「#2525. 「言語は変化する,ただそれだけ」」 ([2016-03-26-1]) で McMahon から引用した文章でも指摘されているとおり,現在,多くの歴史言語学者は,この第1の意味での evolution を前提としていない.この意味は,すでに言語学史的なものとなっている.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2016-03-26 Sat

■ #2525. 「言語は変化する,ただそれだけ」 [language_change][evolution][teleology][language_myth][unidirectionality][history_of_linguistics]

言語学者でない一般の多くの人々には,言語変化を進歩ととらえたり,逆に堕落とみなす傾向がみられる.言語進化を価値観をもって解釈する慣行だ.この見方については「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) や「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) で話題にした.

しかし,現代の言語学者,特に歴史言語学者は,言語はそのような価値観とは無関係に,ただただ変化するものとして理解しており,それ以上でも以下でもないと主張する.この立場については「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) や「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) で紹介した.この現代的な立場をずばり要約している1節を McMahon (324) に見つけたので,引用しておきたい.

The modern view, at least of historical linguists if not the general public, is simply that languages change; we may try to describe and explain the processes of change, and we may set up a complementary typology which will include a classification of languages as isolating, agglutinating or inflecting; but this morphological typology has no special status and certainly does not represent an evolutionary scale. In general, we have no right to attack change as decay or to exalt it as progress. It is true . . . that individual changes may aid or impair communication to a limited extent, but there is no justification for seeing change as cumulative progress or decline: modern languages, attested extinct ones, and even reconstructed ones are all at much the same level of structural complexity or communicative efficiency. We cannot argue that some languages, or stages of languages, are better than others . . . .

ここでは,言語変化は全体として特に進歩や堕落というような価値観を伴った一定の方向を目指しているわけではないが,個々の変化については,限られた程度においてコミュニケーションの助けになったり妨げになったりすることもあると述べられている点が注目に値する.これは,「#2513. Samuels の "linguistic evolution"」 ([2016-03-14-1]) で引用した Samuels (1) の "every language is of approximately equal value for the purposes for which it has evolved" の「およそ等価」という表現と呼応しているように思われる.

言語(変化)論と言語変化観とは切っても切り離せない.言語変化(論)には,時代の思潮の移り変わりを意識した言語学史的な観点をもって接近していかなければならないだろう.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2016-03-25 Fri

■ #2524. Samuels の "linguistic evolution" (2) [terminology][evolution][language_change]

標題は「#2513. Samuels の "linguistic evolution"」 ([2016-03-14-1]) で一度取り上げた話題だが,再考してみたい.なぜ Samuels は本の題名に "linguistic change" ではなく "linguistic evolution" を用いたのか.Samuels にとって,両者の違いは何なのか.20世紀後半から,一度は地下に潜っていた言語の進化という見方が復権してきた感があるが,Samuels の用語使いを理解することは,現在の言語変化理論を考える上で役に立つだろう.先日,勉強会でこの問題について議論する機会を得て,少し理解が進んだように思うので,以下で Samuels が抱いていると思われる "linguistic evolution" のイメージをスケッチしたい.

前の記事では,私は Samuels にとっての "linguistic evolution" を「継承形態と現在の表現上の要求という相反するものの均衡を保とうとする融通性の高い装置」であり,「言語変化に関する普遍的な方向性を示すというよりは,言語変化に働く潜在的な力学を指していう用語」とみなした.基本的なとらえ方は変わっていないが,理解しやすくするために以下のような図を描いてみた.

language-internal and external factors

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

│ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │

↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓ ↓

conservatism or 'inertia' the pressures that work

│ towards clearer communication

│ │

│ │

↓ ↓

┌──────────────────┐ ┌──────────────────┐

│ the inherited forms │ │the expressive needs of the present │

│ (= the old) │== equilibrium == │ (= the new) │

└────────┬─────────┘ └────────┬─────────┘

│ │

│ │

│ a considerable margin of tolerance │

└──────────────▲─────────────┘

│

│

□

これは,言語の上皿てんびんと,そこに働く様々な力と機構を図示したものである.言語のてんびんの片方の皿には,古いものをそのまま残そうとする「惰性」の力の働きにより,過去から継承されたものが載せられている.もう一方の皿には,現在の環境に即応しようとする圧力の働きにより,新しく生み出されたものが載せられている.古い惰性にせよ新しい圧力にせよ,その力はより外部に位置する言語内的・外的な様々な要因から発しており,その時々によって左の皿に余計に重みをかけることになったり,逆に右の皿にかけることになったりする.てんびんは常に左に右にガタガタしており(場合によっては水平方向へも回転?),その揺れの速度も幅もその時々で異なるほど十分に,遊び,許容,選択の度合いは大きい.しかし,ある程度の時間幅を与えて全体として見れば,てんびんは常にほぼ釣り合っていると言ってよい.

Samuels にとって重要な問題は,上の図のなかで起きる個々の出来事,個々の言語変化というよりも,それらの舞台となる上の図全体を前提とすることなのではないか.言語変化を取り巻く環境や装置,もっといえば言語変化のエコロジーのようなものを提案しているのだろうと思う.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-03-14 Mon

■ #2513. Samuels の "linguistic evolution" [terminology][evolution][language_change]

言語進化論は,近年盛んに唱えられるようになってきた言語(変化)観であり,歴史言語学において1つの潮流となっている.本ブログでは「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]),「#519. 言語の起源と進化を探る研究分野」 ([2010-09-28-1]),「#520. 歴史言語学は言語の起源と進化の研究とどのような関係にあるか」 ([2010-09-29-1]),「#2260. 言語進化論の課題」 ([2015-07-05-1]) ほか evolution の各記事で関連する話題を取り上げてきた.

Samuels (1) は早くから "linguistic evolution" を論じて言語変化を研究した論者の1人だが,その古典的著作の冒頭で "linguistic change" ではなくあえて "linguistic evolution" という用語をタイトルに用いた理由について述べている.

The title of this book ('Linguistic Evolution') was chosen in preference to 'Linguistic Change' although it is about linguistic change. This is because its purpose is to attempt an examination of the large complex of different factors involved, and the title 'Linguistic Change' might have entailed an oversimplification.

言語変化には複数の要因が複雑に関与しており (multiple causation of language change),その複雑さをあまりに単純化してただ "change" として扱うことに抵抗があるということのようだ.上の引用に続けて,Samuels (1) は "linguistic evolution" という用語が誤解を招きやすいことをも認めており,注意を促している."evolution" が「進歩,前進」という道徳的な含意をもつことがあるからだろう.

Nevertheless 'evolution' is itself open to the misunderstanding that some sort of progress is implied, that a clearer or more effective means of communication has been achieved as a result of it. That meaning of 'evolution' is not intended here. We are not concerned here with the prehistoric origins of human language, and, as has often been pointed out, there is today no such thing as a 'primitive' language, every language is of approximately equal value for the purposes for which it has evolved, whether it belongs to an advanced or a primitive culture.

では,Samuels のいう "linguistic evolution" とはいかなるものか.それは,継承形態と現在の表現上の要求という相反するものの均衡を保とうとする融通性の高い装置ということのようだ.

. . . it would appear, on the one hand, that both externally and internally in language development an equilibrium must be maintained between the old and the new, between the inherited forms and the expressive needs of the present; but at the same time, that the margin of tolerance and choice in the maintenance of that equilibrium is probably fairly wide, except, that is, for certain especial points of pressure that vary in each era. It is in that sense that 'evolution' is intended here.

Samuels にとって(そして,現在の多くの言語進化論者にとって),"linguistic evolution" とは,言語変化に関する普遍的な方向性を示すというよりは,言語変化に働く潜在的な力学を指していう用語である.

・ Samuels, M. L. Linguistic Evolution with Special Reference to English. London: CUP, 1972.

2015-11-03 Tue

■ #2381. Gould and Vrba の外適応 (2) [exaptation][terminology][evolution][causation][language_change]

昨日に続いて,Gould and Vrba の外適応 (exaptation) の話題.Gould and Vrba (11--13) は,進化論における外適応という用語と概念の重要性を4点ほど指摘している.

(1) 外適応は,従来の "preadaptation" に付随する目的論 (teleology) 的な含意を払拭してくれる.従来の "preadaptation" は,新しい用語体系においては "preaptation" と呼ぶべきものであり,その事実の前において考えられた "exaptation" の一種,すなわち "potential, but unrealized, exaptations" (11) とみなすことができる.

(2) 第1に外適応,第2に適用という順序."Feathers, in their basic design, are exaptations for flight, but once this new effect was added to the function of thermoregulation as an important source of fitness, feathers underwent a suite of secondary adaptations (sometimes called post-adaptations) to enhance their utility in flight" (11). 外適応によって生まれた性質が,その後,適用の過程を経てさらに機能的になってゆくということは,ごく普通のことである.

(3) 外適応の資源は無限であり,柔軟性に富む."[T]he enormous pool of nonaptations must be the wellspring and reservoir of most evolutionary flexibility. We need to recognize the central role of 'cooptability for fitness' as the primary evolutionary significance of ubiquitous nonaptation in organisms" (12). 関連して,"[A]ll exaptations originate randomly with respect to their effects" (12) である.

(4) 外適応をもたらした資源は,nonaptation だったかもしれないし adaptation だったかもしれない."Exaptations . . . are not fashioned for their current role and reflect no attendant process beyond cooptation . . .; they were built in the past either as nonaptive by-products or as adaptations for different roles."

Gould and Vrba (13) は,結論として次のように述べている.

We suspect . . . that the subjects of nonaptation and cooptability are of paramount importance in evolution. . . . The flexibility of evolution lies in the range of raw material presented to processes of selection.

これは,「#2155. 言語変化と「無為の喜び」」 ([2015-03-22-1]) で引用した Lass の言語変化における "The joys of idleness" に直接通じる考え方である.

・ Gould, Stephen Jay and Elizabeth S. Vrba. "Exaptation --- A Missing Term in the Science of Form." Paleobiology 8.1 (1982): 4--15.

2015-11-02 Mon

■ #2380. Gould and Vrba の外適応 (1) [exaptation][terminology][evolution][diachrony][teleology]

昨日の記事「#2379. 再帰代名詞の外適応」 ([2015-11-01-1]) でも取り上げた外適応 (exaptation) は,本来,生物進化の用語である.「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]) で触れたように,Gould and Vrba による生物進化論の外適応を,生物学にもよく通じた言語学者 Lass が,言語変化に当てはめたのだった.

Gould and Vrba の論文は,それほど長い論文ではないが,啓発的である.生物学の門外漢でも読めるほどの一般性を備えており,だからこそ言語学へも適用する余地があったのだろう.進化論における術語の整理を通じて,対応する概念の相互関係を明らかにしようとした論文であり,それらの術語や概念は,確かに工夫すれば言語変化にも当てはめることができるように思われる.論文冒頭の要旨 (4) が,素晴らしく的を射ているので,そのまま引用したい.

Adaptation has been defined and recognized by two different criteria: historical genesis (features built by natural selection for their present role) and current utility (features now enhancing fitness no matter how they arose). Biologists have often failed to recognize the potential confusion between these different definitions because we have tended to view natural selection as so dominant among evolutionary mechanisms that historical process and current product become one. Yet if many features of organisms are non-adapted, but available for useful cooptation in descendants, then an important concept has no name in our lexicon (and unnamed ideas generally remain unconsidered): features that now enhance fitness but were not built by natural selection for their current role. We propose that such features be called exaptations and that adaptation be restricted, as Darwin suggested, to features built by selection for their current role. We present several examples of exaptation, indicating where a failure to conceptualize such an idea limited the range of hypotheses previously available. We explore several consequences of exaptation and propose a terminological solution to the problem of preadaptation.

通時的な発生と共時的な有用性の混同という問題,そしてそれを是正するための新用語としての exaptation は,言語論においても役立つはずである.コミュニケーションに役に立つべく通時的に発生してきた言語項 (adaptation) と,偶然に発達して結果的に役立つ機能を得た言語項 (exaptation) を区別しておくことは,確かに必要だろう.また,exaptation は,目的論 (teleology) 的な言語変化観に対抗する用語と概念を与えてくれるようにも思える.

Gould and Vrba (5) は,"A taxonomy of fitness" と題する表で,以下のように関連する術語を整理している.

| Process | Character | Usage | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural selection shapes the character for a current use --- adaptation | adaptation | aptation | function |

| A character, previously shaped by natural selection for a particular function (an adaptation), is coopted for a new use --- cooptation | exaptation | effect | |

| A character whose origin cannot be ascribed to the direct action of natural selection (a nonaptation), is coopted for a current use --- cooptation | |||

これらの術語群を言語変化に(部分的にであれ)適用するには試行錯誤が必要なことはいうまでもないが,この方向には多くの可能性が開かれているように直感される.

・ Gould, Stephen Jay and Elizabeth S. Vrba. "Exaptation --- A Missing Term in the Science of Form." Paleobiology 8.1 (1982): 4--15.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-07-05 Sun

■ #2260. 言語進化論の課題 [evolution][language_change][linguistics]

近年,evolution, mutation, chance, natural selection, variation, exaptation など,進化生物学の用語を借りた言語進化論 (linguistic evolution) が盛んになってきている.言語における「進化」の考え方については様々な議論があり,本ブログでも「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]),「#519. 言語の起源と進化を探る研究分野」 ([2010-09-28-1]),「#520. 歴史言語学は言語の起源と進化の研究とどのような関係にあるか」 ([2010-09-29-1]) ほか evolution の各記事でも関連する話題を取り上げてきた.言語における「進化」を巡る議論を要領よくまとめたものとしては,McMahon の12章 (314--40) を薦めたい.McMahon (337) は,今後この方向での言語変化の研究が有望とみているが,一方で取り組まなければならない問題は少なくないとも述べている.

. . . many questions remain if we are to make full use of our evolutionary terminology in historical linguistics. We do not know which units selection might operate on in language history; are they words, rules, speakers, or languages themselves? We do not know whether linguistic evolution is governed only by general, universal tendencies, or whether these can be overridden by language-specific factors. And we have yet to formulate the conditions under which variation and selection might conspire to produce regularity.

選択 (selection) が作用する単位は何かという問題は本質的である.音素,形態素,語,句,節,文,韻律,規則,話者,話者集団,言語そのもの等々,種々の言語理論が設定するありとあらゆる単位が候補となりうる.このことは,ある単位に着目して言語の進化や変化を記述するということが,ある仮説に基づく行為であるということを思い起こさせる.

ちなみに,上の McMahon の文章は,先日参加してきた SHEL-9/DSNA-20 Conference (The 9th Studies in the History of the English Language Conference) で,独自の言語変化論を展開する Nikolaus Ritt が基調講演にて部分的に引用・参照していたものでもある.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2015-03-13 Fri

■ #2146. 英語史の統語変化は,語彙投射構造の機能投射構造への外適応である [exaptation][grammaticalisation][syntax][generative_grammar][unidirectionality][drift][reanalysis][evolution][systemic_regulation][teleology][language_change][invisible_hand][functionalism]

「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) でみたように,英語史で生じてきた主要な統語変化はいずれも「機能範疇の創発」として捉えることができるが,これは「機能投射構造の外適応」と換言することもできる.古英語以来,屈折語尾の衰退に伴って語彙投射構造 (Lexical Projection) が機能投射構造 (Functional Projection) へと再分析されるにしたがい,語彙範疇を中心とする構造が機能範疇を中心とする構造へと外適応されていった,というものだ.

文法化の議論では,生物進化の分野で専門的に用いられる外適応 (exaptation) という概念が応用されるようになってきた.保坂 (151) のわかりやすい説明を引こう.

外適応とは,たとえば,生物進化の側面では,もともと体温保持のために存在していた羽毛が滑空の役に立ち,それが生存の適応価を上げる効果となり,鳥類への進化につながったという考え方です〔中略〕.Lass (1990) はこの概念を言語変化に応用し,助動詞 DO の発達も一種の外適応(もともと使役の動詞だったものが,意味を無くした存在となり,別の用途に活用された)と説明しています.本書では,その考えを一歩進め,構造もまた外適応したと主張したいと思います.〔中略〕機能範疇はもともと一つの FP (Functional Projection) と考えられ,外適応の結果,さまざまな構造として具現化するというわけです.英語はその通時的変化の過程の中で,名詞や動詞の屈折形態の消失と共に,語彙範疇中心の構造から機能範疇中心の構造へと移行してきたと考えられ,その結果,冠詞,助動詞,受動態,完了形,進行形等の多様な分布を獲得したと言えるわけです.

このような言語変化観は,畢竟,言語の進化という考え方につながる.ヒトに特有の言語の発生と進化を「言語の大進化」と呼ぶとすれば,上記のような言語の変化は「言語の小進化」とみることができ,ともに歩調を合わせながら「進化」の枠組みで研究がなされている.

保坂 (158) は,言語の自己組織化の作用に触れながら,著書の最後を次のように締めくくっている.

こうした言語自体が生き残る道を探る姿は,いわゆる自己組織化(自発的秩序形成とも言われます)と見なすことが可能です.自己組織化とは雪の結晶やシマウマのゼブラ模様等が有名ですが,物理的および生物的側面ばかりでなく,たとえば,渡り鳥が作り出す飛行形態(一定の間隔で飛ぶ姿),気象現象,経済システムや社会秩序の成立などにも及びます.言語の小進化もまさにこの一例として考えられ,言語を常に動的に適応変化するメカニズムを内在する存在として説明でき,それこそ,ことばの進化を導く「見えざる手」と言えるのではないでしょうか.英語における文法化の現象はまさにその好例であり,言語変化の研究がそうした複雑な体系を科学する一つの手段になり得ることを示してくれているのです.

言語変化の大きな1つの仮説である.

・ 保坂 道雄 『文法化する英語』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-02-04 Wed

■ #2109. 鳥の歌とヒトの言語の類似性 [homo_sapiens][anthropology][linguistics][double_articulation][acquisition][origin_of_language][speech_organ][evolution]

ヒトの言語の特徴について,「#1327. ヒトの言語に共通する7つの性質」 ([2012-12-14-1]) や「#1281. 口笛言語」 ([2012-10-29-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきた.そのような議論では,当然ながらヒトの言語が他の動物のもつコミュニケーション手段とは異なる特徴を有することが強調されるのだが,別の観点からみるとむしろ共通する特徴が浮き彫りになることがある.Aitchison (7--9) によれば,ヒトの言語と鳥の歌 (bird-song) には類似点があるという.

(1) まず,すぐに思い浮かぶのはオウムによる口まねだろう.オウムはヒトと同じような意味で「しゃべっている」あるいは「言語を用いている」わけではないし,調音の方法もまるで異なる.しかし,動物界には希少な分節音を発する能力をもっている点では,オウムはヒトと同類だ.

(2) 鳥は先天的な呼び声 (call) と後天的な歌 (song) の2種類の鳴き声をもっている.ヒトにも本能的な叫び声などと後に習得される言語の2種類の発声がある.つまり,鳥の歌とヒトの言語には,後天的に習得されるという共通点がある.

(3) 鳥の歌では,歌を構成する個々の音は単独では意味をなさず,音の連続性が重要である.同様に,ヒトの言語でも,個々の分節音は意味をもたず,通常それが複数組み合わさってできる形態素以上の単位になったときに始めて意味をもつ.この性質は,ヒトの言語の最たる特徴としてしばしば指摘される二重分節 (double_articulation) にほかならないが,鳥の歌にも類似した特徴がみられるということになる.

(4) さらに,同じ種の鳥でも,関連はするが若干異なる種類の歌をさえずることがある.これは,ヒトの言語でいうところの方言にほかならない.California の「みやましとど」 (white-crowned sparrow) というホオジロ科の鳥は,州内や,場合によっては San Francisco 市内ですら,種々の区別される「方言」を示し,熟練した観察者であれば個体の住処がわかるとまで言われる(関連して,東京と京都の鶯のさえずりが方言のように異なるという話も聞いたことがある).

(5) 興味深いことに,作用している機構はまるで異なるだろうが,ヒトの言語も鳥の歌も,通常左脳で制御されているという共通点がある.

(6) 鳥のひなによる歌の習得とヒトの子供の言語習得に似ている点がある.ひなは一人前の鳥としての歌を習得する前に,半人前のさえずりの段階を経る.しかも,早い段階において歌の発達に重要な臨界期があることも知られている.これは,ヒトの言語でいうところの喃語 (babbling) や言語習得の臨界期に対応するようにみえる.

Aichison (8) は,以上の類似点を次のようにまとめている.

In short, both birds and humans produce fluent complex sounds, they both have a double-barrel led, double-layered system involving tunes and dialects, which is controlled by the left half of the brain. Youngsters have a type of sub-language en route to the full thing, and are especially good at acquiring the system in the early years of their lives.

だが,もちろん相違点も大きいという点は見逃してはならない.例えば,鳥でさえずりをするのは,雄のみである.また,鳥の歌は,ヒトの言語と比べて,個体差が大きいという.場合によっては数キロの距離を経てコミュニケーションを取れるというのも,鳥の歌の顕著な特徴だろう.鳥の歌の主たる目的が求愛であるのに対して,ヒトの言語の目的はずっと広範である.

鳥の歌とヒトの言語の類似性(と異質性)を比較してわかることは,異なる種にも似たような特徴が独立して生じうるということである.両者の接点を手がかりにヒトの言語の起源を求めようとしても,おそらくうまくいかないのではないか.

・ Aitchison, Jean. The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2014-10-07 Tue

■ #1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度 [borrowing][contact][pragmatics][discourse_marker][subjectification][intersubjectification][evolution]

言語接触の分野では,借用されやすい言語項はあるかという問題,すなわち借用尺度 (scale of adoptability, or borrowability scale) の問題を巡って議論が繰り広げられてきた.Thomason and Kaufman は借用され得ない言語項はないと明言しているが,そうだとしても借用されやすい項目とそうでない項目があることは認めている.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) などで議論の一端をみてきたが,いずれも形式的な基準による尺度だった.およそ,語を代表とする自立性の高い形態が最も借用されやすく,次に派生形態素,屈折形態素などの拘束された形態が続くといった順序だ.そのなかに音韻,統語,意味などの借用も混じってくるが,これらは順序としては比較的後のほうである.

自立語が最も借用されやすく統語的な文法項目が最も借用されにくいという形式的な尺度は,直感的にも受け入れやすく,個々の例外的な事例はあるにせよ,およそ同意されているといってよいだろう.ところで,形式的な基準ではなく機能的な基準による借用尺度というものはあり得るだろうか.この点について Matras (209--10) が興味深い指摘をしている.

. . . it was proposed that borrowing hierarchies are sensitive to functional properties of discourse organization and speaker-hearer interaction. Items expressing contrast and change are more likely to be borrowed than items expressing addition and continuation. Discourse markers such as tags and interjections are on the whole more likely to be borrowed than conjunctions, and categories expressing attitudes to propositions (such as focus particles, phrasal adverbs like still or already, or modals) are more likely to be borrowed than categories that are part of the propositional content itself (such as prepositions, or adverbs of time and place). Contact susceptibility is thus stronger in categories that convey a stronger link to hearer expectations, indicating that contact-related change is initiated through the convergence of communication patterns . . . . In the domain of phonology and phonetics, sentence melody, intonation and tones appear more susceptible to borrowing than segmental features. One might take this a step further and suggest that contact first affects those functions of language that are primary or, in evolutionary perspective, primitive. Reacting to external stimuli, seeking attention, and seeking common ground with a counterpart or interlocutor. Contact-induced language change thus has the potential to help illuminate the internal composition of the grammatical apparatus, and indeed even its evolution.

付加詞や間投詞をはじめとする談話標識 (discourse_marker) や態度を表わす小辞など,聞き手を意識したコミュニケーション上の機能をもつ表現のほうが,命題的・指示的な機能をもつ表現よりも借用されやすいという指摘である.だが,談話標識はたいてい文の他の要素から独立している,あるいは完全に独立してはいなくとも,ある程度の分離可能性は保持している.つまり,この機能的な基準による尺度は,統語形態的な独立性や自由度と関連している限りにおいて,従来の形式的な基準による尺度とは矛盾しない.むしろ,従来の形式的な基準のなかに取り込まれる格好になるのではないか.

と,そこまで考察したところで,しかし,上の引用の後半で述べられている言語音に関する借用尺度のくだりでは,分節音よりも「かぶさり音韻」である種々の韻律的要素のほうが借用されやすいとある.従来の形式的な基準では,分節音や音素の借用への言及はあったが,韻律的要素の借用はほとんど話題にされたことがないのではないか(昨日の記事「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]) の (6) を参照).韻律的要素が相対的に借用されやすいという指摘と合わせて,引用の前半部分の内容を評価すると,機能的な借用尺度の提案に一貫性が感じられる.話し手と聞き手のコミュニケーションに直接関与する言語項,言い換えれば(間)主観性を含む言語項が,そうでないものよりも借用されやすいというのは,言語の機能という観点からみて,確かに合理的だ.言語の進化 (evolution) への洞察にも及んでおり,刺激的な説である.

このように一見なるほどと思わせる説ではあるが,借用された項目の数という点からみると,discourse marker 等の借用は,それ以外の命題的・指示的な機能をもつ表現(典型的には名詞や動詞)と比べて,圧倒的に少ないことは疑いようがない.形式的な基準と機能的な基準が相互にどのような関係で作用し,借用尺度を構成しているのか.多くの事例研究が必要になってくるだろう.

・ Matras, Yaron. "Language Contact." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 203--14.

2014-06-11 Wed

■ #1871. 言語と人種 [race][language_myth][indo-european][comparative_linguistics][evolution][origin_of_language][ethnic_group]

言語に関する根強い俗説の1つに,「言語=人種」というものがある.この俗説を葬り去るには,一言で足りる.すなわち,言語は後天的であり,人種は先天的である,と言えば済む(なお,ここでの「言語」とは,ヒトの言語能力という意味での「言語」ではなく,母語として習得される個別の「言語」である).しかし,人々の意識のなかでは,しばしばこの2つは分かち難く結びつけられており,それほど簡単には葬り去ることはできない.

過去には,言語と人種の同一視により,関連する多くの誤解が生まれてきた.例えば,19世紀にはインド・ヨーロッパ語 (the Indo-European) という言語学上の用語が,人種的な含意をもって用いられた.インド・ヨーロッパ語とは(比較)言語学上の構築物にすぎないにもかかわらず,数千年前にその祖語を話していた人間集団が,すなわちインド・ヨーロッパ人(種)であるという神話が生み出され,言語と人種とが結びつけられた.祖語の故地を探る試みが,すなわちその話者集団の起源を探る試みであると解釈され,彼らの最も正統な後継者がドイツ民族であるとか,何々人であるとかいう議論が起こった.20世紀ドイツのナチズムにおいても,ゲルマン語こそインド・ヨーロッパ語族の首長であり,ゲルマン民族こそインド・ヨーロッパ人種の代表者であるとして,言語と人種の強烈な同一視がみられた.

しかし,この俗説の誤っていることは,様々な形で確認できる.インド・ヨーロッパ語族で考えれば,西ヨーロッパのドイツ人と東インドのベンガル人は,それぞれ親戚関係にあるドイツ語とベンガル語を話しているとはいえ,人種として近いはずだと信じる者はいないだろう.また,一般論で考えても,どんな人種であれヒトとして生まれたのであれば,生まれ落ちた環境にしたがって,どんな言語でも習得することができるということを疑う者はいないだろう.

このように少し考えれば分かることなのだが,だからといって簡単には崩壊しないのが俗説というものである.例えば,ルーマニア人はルーマニア語というロマンス系の言語を話すので,ラテン系の人種に違いないというような考え方が根強く抱かれている.実際にDNAを調査したらどのような結果が出るかはわからないが,ルーマニア人は人種的には少なくともスペイン人やポルトガル人などと関係づけられるのと同程度,あるいはそれ以上に,近隣のスラヴ人などとも関係づけられるのではないだろうか.何世紀もの間,近隣の人々と混交してきたはずなので,このように予想したとしてもまったく驚くべきことではないのだが,根強い俗説が邪魔をする.

言語学の専門的な領域ですら,この根強い信念は影を落とす.現在,言語の起源を巡る主流派の意見では,言語の起源は,約数十万年前のホモ・サピエンスの出現とホモ・サピエンスその後の発達・展開と関連づけられて論じられることが多い.人種がいまだそれほど拡散していないと時代という前提での議論であるとはしても,はたしてこれは件の俗説に陥っていないと言い切れるだろうか.

関連して,Trudgill (43--44) の議論も参照されたい.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2014-02-15 Sat

■ #1755. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード (2) [evolution][origin_of_language][timeline][homo_sapiens][anthropology][punctuated_equilibrium]

「#1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード」 ([2014-02-09-1]) で,言語の発現・進化・伝播について Aitchison の "language bonfire" 仮説を紹介した.言語学の「入門への入門書」とうたわれている,加藤重広著『学びのエクササイズ ことばの科学』を読んでいたところ,この仮説がわかりやすく紹介されていた.

加藤 (23--24) によると,現在の人類学の研究成果が明らかするところによれば,他の原人の祖先から,現生人類およびネアンデルタール人の共通の祖先が分岐したのは約100万年前のことである.そして,後者2つの祖先が互いに分岐したのは約50万年前.2万5千年前くらいにネアンデルタール人が滅びるまでは,現生人類と共存していたことがわかっている.一方,現生人類がアフリカに誕生したのは約20万年前のことである.この現生人類は7--6万年前にアフリカから世界へ拡散し,1万5千年前くらいに北米に達した.

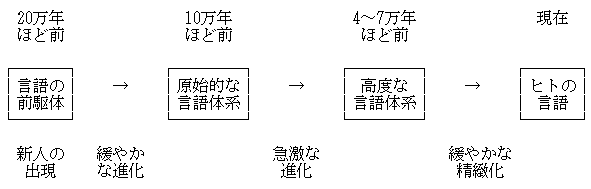

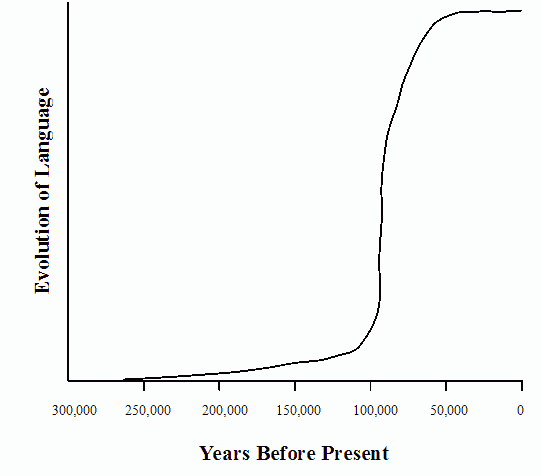

上記の現生人類の歴史のなかで,その誕生期前後に言語の前駆体なるものも同時に発現したと考えられる(前駆体については,「#544. ヒトの発音器官の進化と前適応理論」 ([2010-10-23-1]) を参照).その後しばらくは,言語の前駆体は緩やかな進化を示すにすぎず,10万年ほど前にようやく原始的な言語の水準に達しつつあったとされる.ところが,10万年ほど前の時期に,急激な言語の進化が生じる.そして,出アフリカの時期を中心に,歴史時代の言語体系にほぼ匹敵する高度な言語体系が発達した.その後は,長い尾を引く緩やかな精緻化の時期に入り,現在に至る.これが,"language bonfire" 仮説である.加藤 (24) から図示すると,以下のようになる.

関連して,「#41. 言語と文字の歴史は浅い」 ([2009-06-08-1]),「#751. 地球46億年のあゆみのなかでの人類と言語」 ([2011-05-18-1]),「#1544. 言語の起源と進化の年表」 ([2013-07-19-1]) も参照.

・ 加藤 重広 『学びのエクササイズ ことばの科学』 ひつじ書房,2007年.

2014-02-09 Sun

■ #1749. 初期言語の進化と伝播のスピード [evolution][origin_of_language][punctuated_equilibrium][speed_of_change]

言語の起源,初期言語の進化と伝播については様々な節が唱えられており,本ブログでも origin_of_language や evolution の記事で関連する話題を取り上げてきた.比喩に定評のある Aitchison によれば,言語の発現と初期の進化には,3つの仮説がある.

1つ目は,Aitchison が "rabbit-out-of-a-hat" と呼んでいるもので,言語は手品師が帽子からウサギを取り出すかのように突如として生じたのだとする説だ.「#544. ヒトの発音器官の進化と前適応理論」 ([2010-10-23-1]) の記事で紹介したスパンドレル理論に相当するもので,Chomsky などが主唱者である."What use is half a wing for flying?" という進化観を背景に,言語が中途半端に発達した段階というものは想像できないとする.この説によると,発現した直後の言語には,現代の言語にみられる複雑な機構がすでに備わっていたということになる.

2つ目は,"snail-up-a-wall" とでも呼ぶべき仮説で,言語は前段階から連続的に発生し,その後も何千年,何万年という期間にわたってゆっくりと一定速度で進化していったとするものである.壁をノロノロと這うカタツムリの比喩である.しかし,生物進化において,この仮説に合致するような型がないことから,言語の進化にも当てはまらないのではないかとされる.

3つ目は,上記2つを組み合わせたような仮説で,Aitchison は "fits-and-starts" と呼んでいる.この説によると,言語の発現と進化は,停滞期と著しい成長期とが交互に繰り返される様式に特徴づけられるとする.「#1397. 断続平衡モデル」 ([2013-02-22-1]) で紹介した punctuated_equilibrium にも連なる考え方だ.

しかし,Aitchison はいずれの説も採らず,第4の仮説として,すべてを組み合わせたような折衷案を出す.本人は,これを "language bonfire" と呼んでいる.

Probably, some sparks of language had been flickering for a very long time, like a bonfire in which just a few twigs catch alight at first. Suddenly, a flame leaps between the twigs, and ignites the whole mass of heaped-up wood. Then the fire slows down and stabilizes, and glows red-hot and powerful. . . . Probably, a simplified type of language began to emerge at least as early as 250,000 BP. Piece by piece, the foundations were slowly put in place. Somewhere between 100,000 and 75,000 BP perhaps, language reached a critical stage of sophistication. Ignition point arrived, and there was a massive blaze, during which language developed fast and dramatically. By around 50,000 BP it was slowing down and stabilizing as a steady long-term glow. (60--61)

これは,S字曲線モデルと言い換えてもよいだろう.引用内に示されているタイムスパンでグラフを描くと,次のようになる.

初期言語の進化についての仮説は上記の通りだが,初期言語が人々の間に伝播していった様式についてはどうだろうか.この2つは区別すべき異なる問題である.Aitchison は,伝播については一気に広まる "language bushfire" の見解を採用している.グラフに描くならば,急な傾きをもつ直線あるいは曲線ということになろうか.

. . . there's a distinction between language emergence (the bonfire) and its diffusion---the spread to other humans (a bush fire). . . . Once evolved, language could have swept through the hominid world like a bush fire. It would have given its speakers an enormous advantage, and they would have been able to impose their will on others, who might then learn the language. (61--62)

・ Aitchison, Jean. The Seeds of Speech: Language Origin and Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2014-01-19 Sun

■ #1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観 [language_change][teleology][evolution][unidirectionality][drift][history_of_linguistics][artificial_language][language_myth]

英語史の授業で英語が経てきた言語変化を概説すると,「言語はどんどん便利な方向へ変化してきている」という反応を示す学生がことのほか多い.これは,「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) の (2) に挙げた「言語変化はより効率的な状態への緩慢な進歩である」と同じものであり,言語進歩観とでも呼ぶべきものかもしれない.しかし,その記事でも述べたとおり,言語変化は進歩でも堕落でもないというのが現代の言語学者の大方の見解である.ところが,かつては,著名な言語学者のなかにも,言語進歩観を公然と唱える者がいた.デンマークの英語学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) もその1人である.

. . . in all those instances in which we are able to examine the history of any language for a sufficient length of time, we find that languages have a progressive tendency. But if languages progress towards greater perfection, it is not in a bee-line, nor are all the changes we witness to be considered steps in the right direction. The only thing I maintain is that the sum total of these changes, when we compare a remote period with the present time, shows a surplus of progressive over retrogressive or indifferent changes, so that the structure of modern languages is nearer perfection than that of ancient languages, if we take them as wholes instead of picking out at random some one or other more or less significant detail. And of course it must not be imagined that progress has been achieved through deliberate acts of men conscious that they were improving their mother-tongue. On the contrary, many a step in advance has at first been a slip or even a blunder, and, as in other fields of human activity, good results have only been won after a good deal of bungling and 'muddling along.' (326)

. . . we cannot be blind to the fact that modern languages as wholes are more practical than ancient ones, and that the latter present so many more anomalies and irregularities than our present-day languages that we may feel inclined, if not to apply to them Shakespeare's line, "Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms," yet to think that the development has been from something nearer chaos to something nearer kosmos. (366)

Jespersen がどのようにして言語進歩観をもつに至ったのか.ムーナン (84--85) は,Jespersen が1928年に Novial という補助言語を作り出した背景を分析し,次のように評している(Novial については「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]) を参照).

彼がそこへたどり着いたのはほかの人の場合よりもいっそう,彼の論理好みのせいであり,また,彼のなかにもっとも古くから,もっとも深く根をおろしていた理論の一つのせいであった.その理論というのは,相互理解の効率を形態の経済性と比較してみればよい,という考えかたである.それにつづくのは,平均的には,任意の一言語についてみてもありとあらゆる言語についてみても,この点から見ると,正の向きの変化の総和が不の向きの総和より勝っているものだ,という考えかたである――そして彼は,もっとも普遍的に確認されていると称するそのような「進歩」の例として次のようなものを列挙している.すなわち,音楽的アクセントが次第に単純化すること,記号表現部〔能記〕の短縮,分析的つまり非屈折的構造の発達,統辞の自由化,アナロジーによる形態の規則化,語の具体的な色彩感を犠牲にした正確性と抽象性の増大である.(『言語の進歩,特に英語を照合して』) マルティネがみごとに見てとったことだが,今日のわれわれにはこの著者のなかにあるユートピア志向のしるしとも見えそうなこの特徴が,実は反対に,ドイツの比較文法によって広められていた神話に対する当時としては力いっぱいの戦いだったのだと考えて見ると,実に具体的に納得がいく.戦いの相手というのは,諸言語の完全な黄金時期はきまってそれらの前史時代の頂点に位置しており,それらの歴史はつねに形態と構造の頽廃史である,という神話だ.(「語の研究」)

つまり,Jespersen は,当時(そして少なからず現在も)はやっていた「言語変化は完全な状態からの緩慢な堕落である」とする言語堕落観に対抗して,言語進歩観を打ち出したということになる.言語学史的にも非常に明快な Jespersen 評ではないだろうか.

先にも述べたように,Jespersen 流の言語進歩観は,現在の言語学では一般的に受け入れられていない.これについて,「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) 及び「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ ジョルジュ・ムーナン著,佐藤 信夫訳 『二十世紀の言語学』 白水社,2001年.

2013-07-19 Fri

■ #1544. 言語の起源と進化の年表 [origin_of_language][evolution][timeline][homo_sapiens][anthropology][language_family]

「#41. 言語と文字の歴史は浅い」 ([2009-06-08-1]),「#751. 地球46億年のあゆみのなかでの人類と言語」 ([2011-05-18-1]) の記事で言語の起源と進化の年表を示したが,コムリー他編の『新訂世界言語文化図鑑 世界の言語の起源と伝播』 (17) より,もう1つの言語年表を示す.

| 50,000 BC | アフリカからの人類の出現(最新の推定年代) | |

| 45,000 BC | ||

| オーストラリアへの移動 | ||

| 40,000 BC | ホモ・サピエンス:言語形態の存在を示唆する複雑な行動様式(物的証拠の存在) | |

| 35,000 BC | ||

| 30,000 BC | ネアンデルタール人の死滅:最も原始的な言語形態 | |

| 25,000 BC | ||

| 20,000 BC | ||

| 15,000 BC | 言語の多様性のピーク(推定):10,000?15,000言語 | |

| 最終氷河期の終わり;ユーラシア語族の拡大 | ||

| 新世界への移動第一波:アメリンド語族 | ||

| 10,000 BC | ||

| 新世界への移動第二波:ナ・デネ語族 | ||

| 5,000 BC | オーストロネシア語族の拡大;台湾への移動 | |

| インド・ヨーロッパ祖語 | ||

| インド・ヨーロッパ語族の最古の記録:ヒッタイト語,サンスクリット語 | ||

| 0 | 古典言語:古代ギリシャ語,ラテン語 | |

| 500 | ロマンス語派,ゲルマン語派の発生;古英語 | |

| 1000 | ||

| 1500 | 植民地時代;ピジンとクレオールの発生;標準言語の拡がり;言語消滅の加速化 | |

| 2000 |

年表で言及されているネアンデルタール人は,ホモ・サピエンスが10万年前に考古学の記録に登場する以前の23万年前から3万年前にかけて生きていた.ネアンデルタール人は喉頭がいまだ高い位置にとどまっており,舌の動きが制限されていたため,発することのできる音域が限られていたと考えられている.しかし,老人や虚弱者の世話,死者の埋葬などの複雑な社会行動を示す考古学的な証拠があることから,そのような社会を成立させる必須要素として初歩的な言語形式が存在したことが示唆される.

以下は,上と同じ年表だが,時間感覚を得られるようスケールを等間隔にとったバージョンである.

| 50,000 BC | アフリカからの人類の出現(最新の推定年代) | |

| 45,000 BC | ||

| オーストラリアへの移動 | ||

| 40,000 BC | ホモ・サピエンス:言語形態の存在を示唆する複雑な行動様式(物的証拠の存在) | |

| 35,000 BC | ||

| 30,000 BC | ネアンデルタール人の死滅:最も原始的な言語形態 | |

| 25,000 BC | ||

| 20,000 BC | ||

| 15,000 BC | 言語の多様性のピーク(推定):10,000?15,000言語 | |

| 最終氷河期の終わり;ユーラシア語族の拡大 | ||

| 新世界への移動第一波:アメリンド語族 | ||

| 10,000 BC | ||

| 新世界への移動第二波:ナ・デネ語族 | ||

| 5,000 BC | オーストロネシア語族の拡大;台湾への移動 | |

| インド・ヨーロッパ祖語 | ||

| インド・ヨーロッパ語族の最古の記録:ヒッタイト語,サンスクリット語 | ||

| 0 | 古典言語:古代ギリシャ語,ラテン語 | |

| 500 | ロマンス語派,ゲルマン語派の発生;古英語 | |

| 1000 | ||

| 1500 | 植民地時代;ピジンとクレオールの発生;標準言語の拡がり;言語消滅の加速化 | |

| 2000 |

・ バーナード・コムリー,スティーヴン・マシューズ,マリア・ポリンスキー 編,片田 房 訳 『新訂世界言語文化図鑑 世界の言語の起源と伝播』 東洋書林,2005年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow