2015-04-21 Tue

■ #2185. 再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現の衰退 [reflexive_pronoun][verb][personal_pronoun][voice][middle_voice]

フランス語学習者から質問を受けた.フランス語には代名動詞というカテゴリーがあるが,英語にはないのはなぜかという疑問である.具体的には,Ma mere se lève tôt. (私の母は早く起きる)のような文における,se leve の部分が代名動詞といわれ,「再帰代名詞+動詞」という構造をなしている.英語風になおせば,My mother raises herself early. という表現である.普通の英語では rise や get up などの動詞を用いるところで,フランス語では代名動詞を使うことが確かに多い.また,ドイツ語でも Du hast dich gar nicht verändert. (You haven't changed at all) のように「再帰代名詞+動詞」をよく使用し,代名動詞的な表現が発達しているといえる.

このような表現は起源的には印欧祖語の中間態 (middle_voice) の用法に遡り,したがって印欧諸語には多かれ少なかれ対応物が存在する.実際,英語にも help oneself, behave oneself, pride oneself on など再帰代名詞と動詞が構造をなす慣用表現は多数ある.しかし,英語ではフランス語の代名動詞のように動詞の1カテゴリーとして設けるほどには発達していないというのは事実だろう.ここにあるのは,質の問題というよりも量の問題ということになる.英語で再帰代名詞を用いた動詞表現が目立たないのはなぜだろうか.

この疑問に正確に回答しようとすれば細かく調査する必要があるが,大雑把にいえば,英語でも古くは再帰代名詞を伴う動詞表現がもっと豊富にあったということである.「他動詞+再帰代名詞」のみならず「自動詞+再帰代名詞」の構造も古くはずっと多く,後者の例は「#578. go him」 ([2010-11-26-1]) や「#1392. 与格の再帰代名詞」 ([2013-02-17-1]) で見たとおりである.このような構造をなす動詞群には現代仏独語とも比較されるものが多く,運動や姿勢を表わす動詞 (ex. go, return, run, sit, stand, turn) ,心的状態を表わす動詞 (ex. doubt, dread, fear, remember) ,獲得を表わす動詞 (buy, choose, get, make, procure, seek, seize, steal) ,その他 (bear, bethink, rest, revenge, sport, stay) があった.ところが,このような表現は近代英語期以降に徐々に廃れ,再帰代名詞を脱落させるに至った.

現代英語でも再帰代名詞の脱落の潮流は着々と続いている.例えば,adjust (oneself) to, behave (oneself), dress (oneself), hide (oneself), identify (oneself) with, prepare (oneself) for, prove (oneself) (to be), wash (oneself), worry (oneself) などでは,再帰代名詞のない単純な構造が好まれる傾向がある.Quirk et al. (358) は,このような動詞を "semi-reflexive verb" と呼んでいる.

以上をまとめれば,英語も近代期までは印欧祖語に由来する中間態的な形態をある程度まで保持し,発展させてきたが,以降は非再帰的な形態に置換されてきたといえるだろう.英語においてこの衰退がなぜ生じたのか,とりわけなぜ近代英語期というタイミングで生じたのかについては,さらなる調査が必要である.再帰代名詞の形態が -self を常に要求するようになり,音韻形態的に重くなったということもあるかもしれない(英語史において再帰代名詞が -self を含む固有の形態を生み出したのは中英語以降であり,それ以前もそれ以後の近代英語期でも,-self を含まない一般の人称代名詞をもって再帰代名詞の代わりに用いてきたことに注意.「#1851. 再帰代名詞 oneself の由来についての諸説」 ([2014-05-22-1]) を参照).あるいは,単体の動詞に対する統語意味論的な再分析が生じたということもあろう.複合的な視点から迫るべき問題のように思われる.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-03-25 Wed

■ #2158. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle." (2) [syntax][word_order][verb][agreement][register]

標題のように said John など伝達動詞が主語の前に置かれる語順について,[2015-02-25-1]の記事の続編を送る.現代英語のこの語順について,Biber et al. (922) は,Quirk et al. の記述と多く重なるが,次のような統語的条件を与えている.

Subject-verb order is virtually the rule where one or more of the following three conditions apply:

The subject is an unstressed pronoun:

"The safety record at Stansted is first class," he said. (NEWS)

The verb phrase is complex (containing auxiliary plus main verb):

"Konrad Schneider is the only one who matters," Reinhold had answered. (FICT)

The verb is followed by a specification of the addressee:

There's so much to living that I did not know before, Jackie had told her happily. (FICT)

LGSWE Corpus での調査によると,被引用文句の後位置では SV も VS も全体的におよそ同じくらいの頻度だというが,FICTIONでは SV がやや多く,NEWSでは VS が強く好まれるなど,傾向が分かれるという.ジャンルとの関係でいえば,前回の記事で触れたように,journalistic writing やおどけた場面では被引用文句の前でも VS が起こることがあるという.この問題は使用域や文体との関連が強そうだ.

伝達動詞であるという語彙・意味的制限,上掲の統語的条件,使用域や文体の関与,これらの要因が複雑に絡み合って said John か John said が決定されるとすれば,この問題は多面的に検討しなければならないことになる.ほかにも語用論的な要因が関与している可能性もありそうだし,他の引用文句を導入する表現や手段との比較も必要だろう.通時的な観点からは,諸条件の絡み合いがいかにして生じてきたのか,また書き言葉における引用符の発達などとの関係があるかどうかなど,興味が尽きない.(後者については,「#2004. ICEHL18 に参加して気づいた学界の潮流など」 ([2014-10-22-1]) で紹介した ICEHL18 の学会で,引用符の発達と quoth の衰退とが関与している可能性があるという趣旨の Colette Moore の口頭発表を聴いたことがある.The ICEHL18 Book of Abstracts (PDF) の pp. 170--71 を参照.)

・ Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad, and Edward Finegan. Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English. Harlow: Pearson Education, 1999.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-03-23 Mon

■ #2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change][bible]

初期近代英語における動詞現在人称語尾 -th → -s の変化については,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回,この問題に関連して Bambas の論文を読んだ.現在の最新の研究成果を反映しているわけではないかもしれないが,要点が非常によくまとまっている.

英語史では,1600年辺りの状況として The Authorised Version で不自然にも3単現の -s が皆無であることがしばしば話題にされる.Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) にも -s が見当たらないことが知られている.ここから,当時,文学的散文では -s は口語的にすぎるとして避けられるのが普通だったのではないかという推測が立つ.現に Jespersen (19) はそのような意見である.

Contemporary prose, at any rate in its higher forms, has generally -th'; the s-ending is not at all found in the A[uthorized] V[ersion], nor in Bacon A[tlantis] (though in Bacon E[ssays] there are some s'es). The conclusion with regard to Elizabethan usage as a whole seems to be that the form in s was a colloquialism and as such was allowed in poetry and especially in the drama. This s must, however, be considered a licence wherever it occurs in the higher literature of that period. (qtd in Bambas, p. 183)

しかし,Bambas (183) によれば,エリザベス朝の散文作家のテキストを広く調査してみると,実際には1590年代までには文学的散文においても -s は容認されており,忌避されている様子はない.その後も,個人によって程度の違いは大きいものの,-s が避けられたと考える理由はないという.Jespersen の見解は,-s の過小評価であると.

The fact seems to be that by the 1590's the -s-form was fully acceptable in literary prose usage, and the varying frequency of the occurrence of the new form was thereafter a matter of the individual writer's whim or habit rather than of deliberate selection.

さて,17世紀に入ると -th は -s に取って代わられて稀になっていったと言われる.Wyld (333--34) 曰く,

From the beginning of the seventeenth century the 3rd Singular Present nearly always ends in -s in all kinds of prose writing except in the stateliest and most lofty. Evidently the translators of the Authorized Version of the Bible regarded -s as belonging only to familiar speech, but the exclusive use of -eth here, and in every edition of the Prayer Book, may be partly due to the tradition set by the earlier biblical translations and the early editions of the Prayer Book respectively. Except in liturgical prose, then, -eth becomes more and more uncommon after the beginning of the seventeenth century; it is the survival of this and not the recurrence of -s which is henceforth noteworthy. (qtd in Bambas, p. 185)

だが,Bambas はこれにも異議を唱える.Wyld の見解は,-eth の過小評価であると.つまるところ Bambas は,1600年を挟んだ数十年の間,-s と -th は全般的には前者が後者を置換するという流れではあるが,両者並存の時代とみるのが適切であるという意見だ.この意見を支えるのは,Bambas 自身が行った16世紀半ばから17世紀半ばにかけての散文による調査結果である.Bambas (186) の表を再現しよう.

| Author | Title | Date | Incidence of -s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascham, Roger | Toxophilus | 1545 | 6% |

| Robynson, Ralph | More's Utopia | 1551 | 0% |

| Knox, John | The First Blast of the Trumpet | 1558 | 0% |

| Ascham, Roger | The Scholmaster | 1570 | 0.7% |

| Underdowne, Thomas | Heriodorus's Anaethiopean Historie | 1587 | 2% |

| Greene, Robert | Groats-Worth of Witte; Repentance of Robert Greene; Blacke Bookes Messenger | 1592 | 50% |

| Nashe, Thomas | Pierce Penilesse | 1592 | 50% |

| Spenser, Edmund | A Veue of the Present State of Ireland | 1596 | 18% |

| Meres, Francis | Poetric | 1598 | 13% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Wonderfull Yeare 1603 | 1603 | 84% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Seuen Deadlie Sinns of London | 1606 | 78% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Defence of Ryme | 1607 | 62% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Collection of the History of England | 1612--18 | 94% |

| Drummond of Hawlhornden, W. | A Cypress Grove | 1623 | 7% |

| Donne, John | Devotions | 1624 | 74% |

| Donne, John | Ivvenilia | 1633 | 64% |

| Fuller, Thomas | A Historie of the Holy Warre | 1638 | 0.4% |

| Jonson, Ben | The English Grammar | 1640 | 20% |

| Milton, John | Areopagitica | 1644 | 85% |

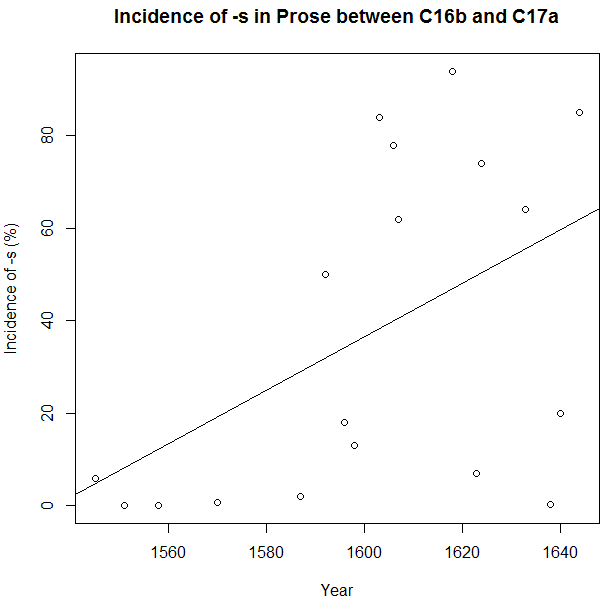

これをプロットすると,以下の通りになる.

この期間では年間0.5789%の率で上昇していることになる.相関係数は0.49である.全体としては右肩上がりに違いないが,個々のばらつきは相当にある.このことを過小評価も過大評価もすべきではない,というのが Bambas の結論だろう.

・ Bambas, Rudolph C. "Verb Forms in -s and -th in Early Modern English Prose". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46 (1947): 183--87.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2015-03-20 Fri

■ #2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え [exaptation][tense][aspect][category][language_change][verb][conjugation][inflection]

昨日の記事「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]) で取り上げた,印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語にかけて生じた時制と相の組み替えについて,より詳しく説明する.印欧祖語で相のカテゴリーを構成していた Present, Perfect, Aorist の区別は,ゲルマン祖語にかけて時制と数のカテゴリーの構成要因としての Present, Preterite 1, Preterite 2 の区別へと移行した.形態的な区別は保持したままに,外適応が起こったことになる.まず対応の概略を図式的に示すと,次のようになる.

(Indo-European) (Germanic) PRESENT ──────── PRESENT PERFECT ──────── PRETERITE 1 AORIST ──────── PRETERITE 2

ゲルマン諸語の弱変化動詞については,印欧祖語時代の PERFECT と AORIST は形態的に完全に融合したので,上図の示すような PRETERITE 1 と 2 の区別はつけられていない.しかし,強変化動詞はもっと保守的であり,かつての PERFECT と AORIST の形態的痕跡を残しながら,2種類の PRETERITE へと機能をシフトさせた(つまり外適応した).(2種類の PRETERITE については,「#42. 古英語には過去形の語幹が二種類あった」 ([2009-06-09-1]) を参照.)

ところで,印欧祖語では動詞の相のカテゴリーは母音階梯 (ablaut) によって標示された.e-grade は PRESENT を,o-grade は PERFECT を,zero-grade あるいは ē-grade は AORIST を表した.一方,古英語のいくつかの強変化動詞の PRESENT, PRETERITE 1, PRETERITE 2 の形態をみると,bīt-an -- bāt -- bit-on, bēod-an -- bēad -- budon, help-an -- healp -- hulpon などとなっている.印欧祖語以降の母音変化により直接は見えにくくなっているが,古英語の3種の屈折変化に見られるそれぞれの母音の違いは,印欧祖語時代の e-grade, o-grade, zero-grade の差に対応する.つまり,3種の屈折変化は音韻形態的には地続きである.したがって,ゲルマン祖語時代にかけて本質的に変化していったのは形態ではなく機能ということになる.おそらくは印欧祖語の相の区別が不明瞭になるに及び,保持された形態的な対立が別のカテゴリー,すなわち時制と数の区別に新たに応用されたということだろう.

Lass (87) によると,この外適応は以下の一連の過程を経て生じたと想定されている.

(i) loss of the (semantic) opposition perfect/aorist; (ii) retention of the diluted semantic content 'past' shared by both (in other words, loss of aspect but retention of distal time-deixis); (iii) retention of the morpho(phono)logical exponents of the old categories perfect and aorist, but divested of their oppositional meaning; (iv) redeployment of the now semantically evacuated exponents as markers of a secondary (concordial) category; in effect re-use of the now 'meaningless' old material to bolster an already existing concordial system, but in quite a new way.

印欧祖語には存在しなかったカテゴリーがゲルマン祖語において新たに創発されたという意味で,この外適応はまさに "conceptual novelty" の事例といえる.

・ Lass, Roger. "How to Do Things with Junk: Exaptation in Language Evolution." Journal of Linguistics 26 (1990): 79--102.

2015-03-12 Thu

■ #2145. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (6) [verb][conjugation][emode][number][agreement][3pp][nptr]

標題については 3pp の各記事で取り上げてきたが,関連する記述をもう1つ見つけたので,以下に記しておきたい.「#1301. Gramley の英語史概説書のコンパニオンサイト」 ([2012-11-18-1]) と「#2007. Gramley の英語史概説書の目次」 ([2014-10-25-1]) で紹介した Gramley (136--37) からの引用である.

Third person {-s} vs. {-(e)th} is a further inflectional point. This distinction is one of the most noticeable in this period [EModE], and it may be used as evidence of the influence of Northern on Southern English. In ME Northerners used the ending {-s} where Southerners used {-(e)th}. In each case the respective inflection could be used in both the third person singular present tense as well as in the whole of the plural . . . . While zero became normal in the plural, in the third person singular present tense there was no such move, and the two forms were in competition with each other both in colloquial London speech and in the written language.

同英語史書のコンパニオンサイトより,6章のための補足資料 (p. 8) に,さらに詳しい解説が載っており有用である.また,そこでは Northern Subject Rule (= Northern Present Tense Rule; cf. nptr, 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1])) にも触れられており,その関連で Lass (166, 185) と Nevalainen and Raumolin-Brunberg (283, 312) への言及もある.

NPTR が南部において適用された結果と思われる複現の -s の例を挙げておこう.

・ they laugh that wins (F1--3, Q1--3; win F4) (Shakespeare, Othello 4.1.121)

・ whereby they make their pottage fat, and therewith driues out the rest with more content. (Deloney, Jack of Newbury 72)

・ For if neither they can doo that they promise & wantes greatest good (Elizabeth, Boethius 48.11)

・ Well know they what they speak that speaks (F1; speak Q) so wisely (Shakespeare, Troilus 3.2.145)

・ when sorrows comes (F1), they come not single spies. (Shakespeare, Hamlet 4.5.73)

・ As surely as your feet hits (F1) the ground they step on (Shakespeare, Twelfth Night 3.4.265)

Shakespeare では版によって複現の -s が現われたり消えたりする例が見られることから,そこには文体的あるいは通時的な含意がありそうである.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ Nevalainen, T. and H. Raumolin-Brunberg. "The Changing Role of London on the Linguistic Map of Tudor and Stuart England." The History of English in a Social Context: A Contribution to Historical Sociolinguistics. Ed. D. Kastovsky and A. Mettinger. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2000. 279--337.

2015-03-09 Mon

■ #2142. 中英語における3単現および複現の語尾の方言分布 [map][laeme][lalme][me_dialect][me][3sp][3pp][verb][conjugation][nptr]

標題の問いに手っ取り早く答えるには,次の表で事足りる(Görlach (68) による表の一部より).

| South | Midland | North | ||

| Present Indicative | 3sg. | -(e)þ | -(e)þ | -(e)s |

| pl. | -(e)þ | -(e)n | -(e)s | |

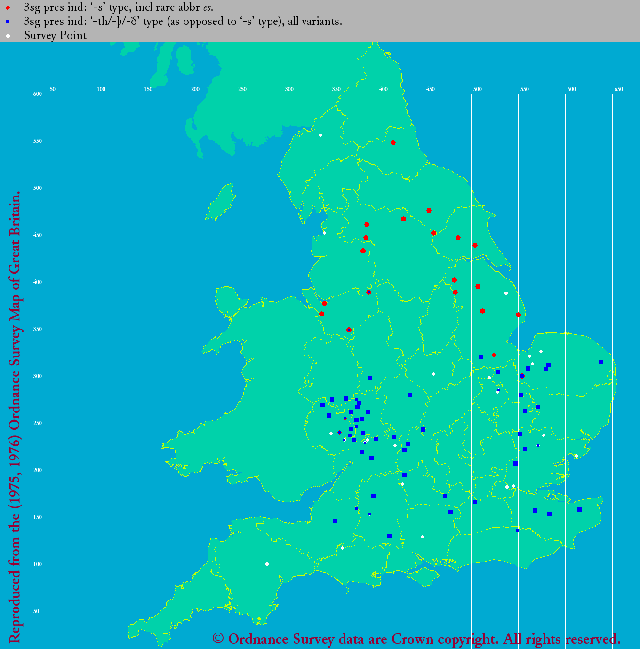

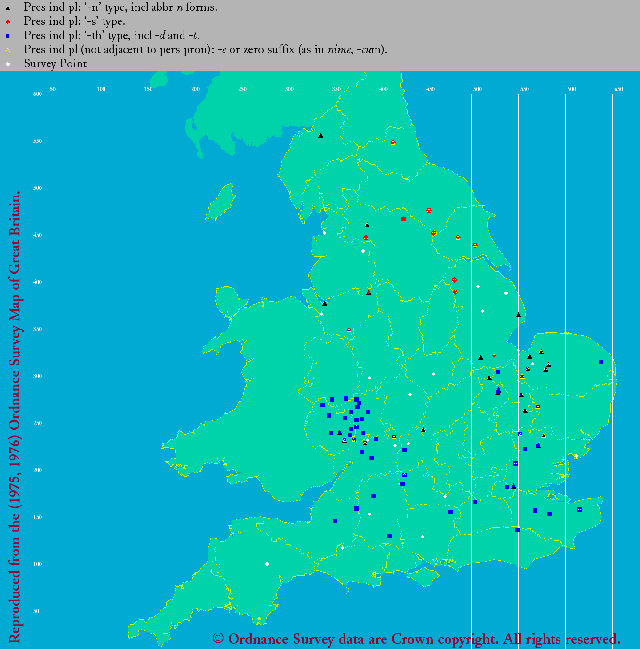

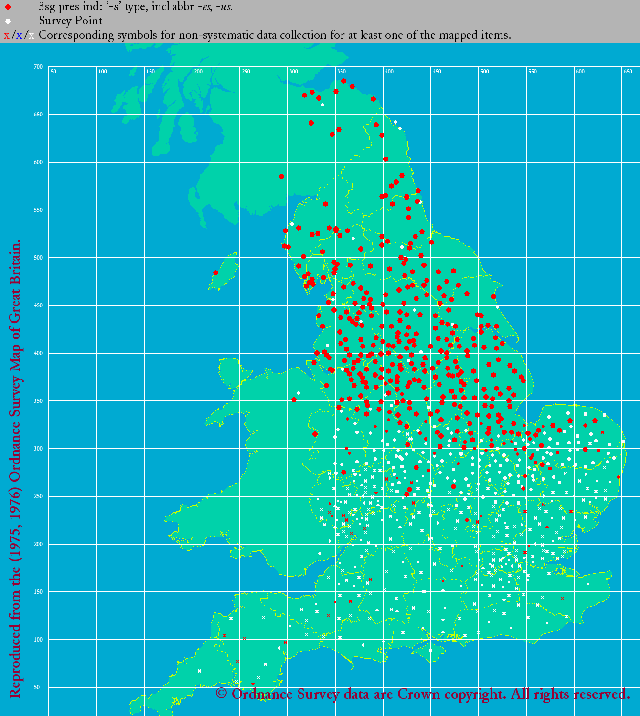

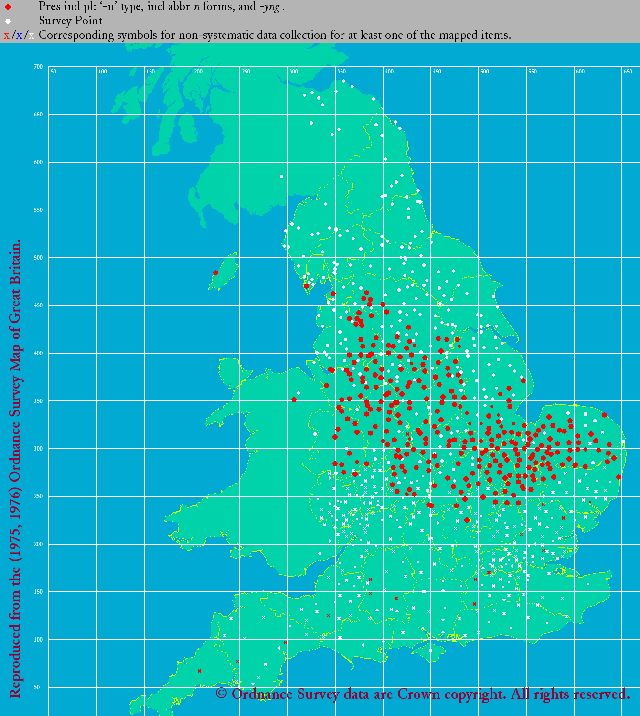

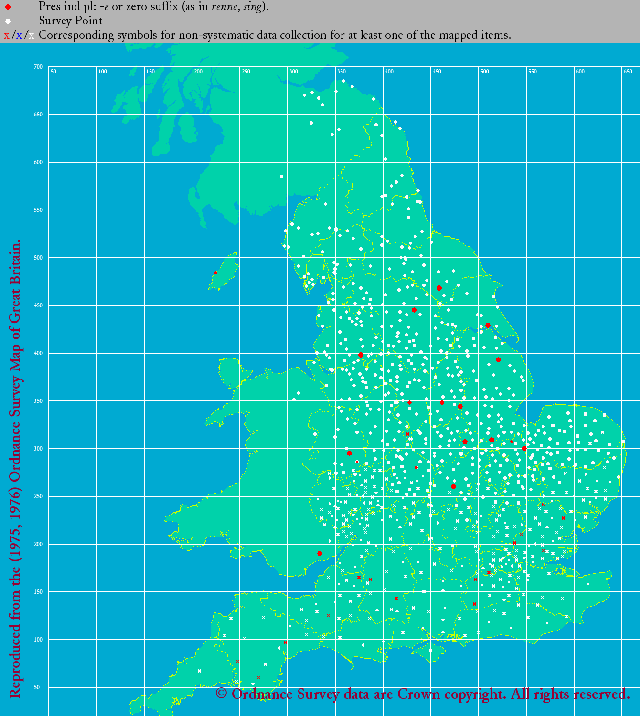

これを地図上に示すと「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) の通りとなるが,より詳しい分布を得たいときには LAEME (初期中英語)と eLALME (後期中英語)を参照するのが便利である (cf. 「#1622. eLALME」 ([2013-10-05-1])) .以下では,両アトラスより得られた地図の画像を貼り付けよう(クリックするとより大きく綺麗な画像が得られる).まずは,1150--1325年をカバーする LAEME より,3単現(左)と複現(右)の語尾の分布をそれぞれ示す.

|

|

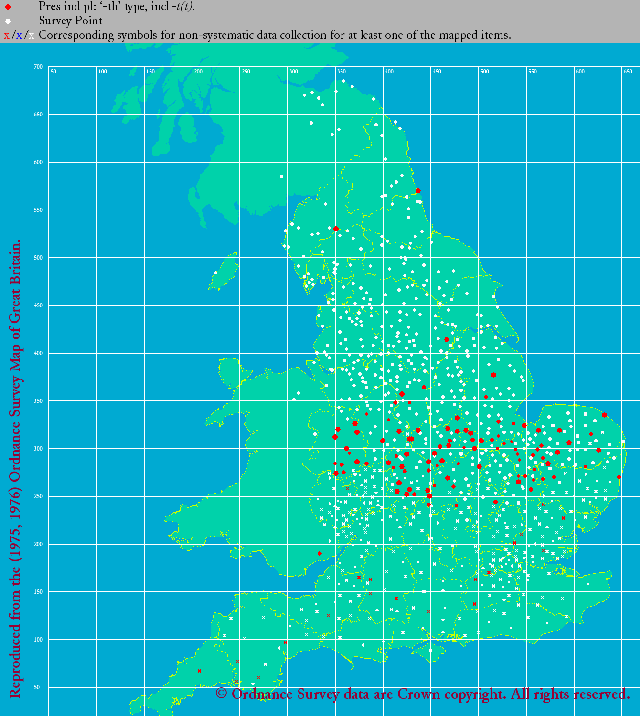

| LAEME: 3sp 's' and 'th' | LAEME: pp 's', 'th', 'n', 'e', and zero |

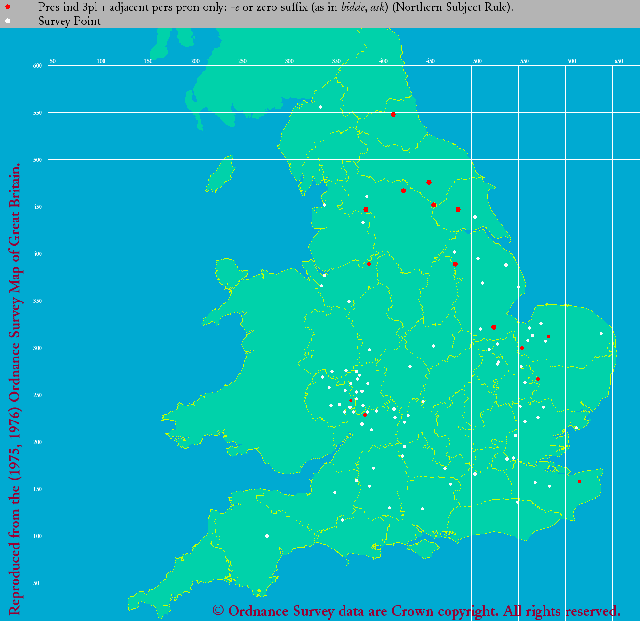

両地図で北部に集まる赤丸が -s を,南部に集まる青四角が -th を表す.右の複現の語尾では東中部その他に黒三角が散在しているが,これは -n 語尾を表す.次に,複数代名詞と接する動詞の現在形が -e またはゼロの語尾をとる "Northern Present Tense Rule" (NPTR; cf. 「#689. Northern Personal Pronoun Rule と英文法におけるケルト語の影響」 ([2011-03-17-1]),nptr) の分布図を見よう.

|

| LAEME: NPTR pp 'e' and zero |

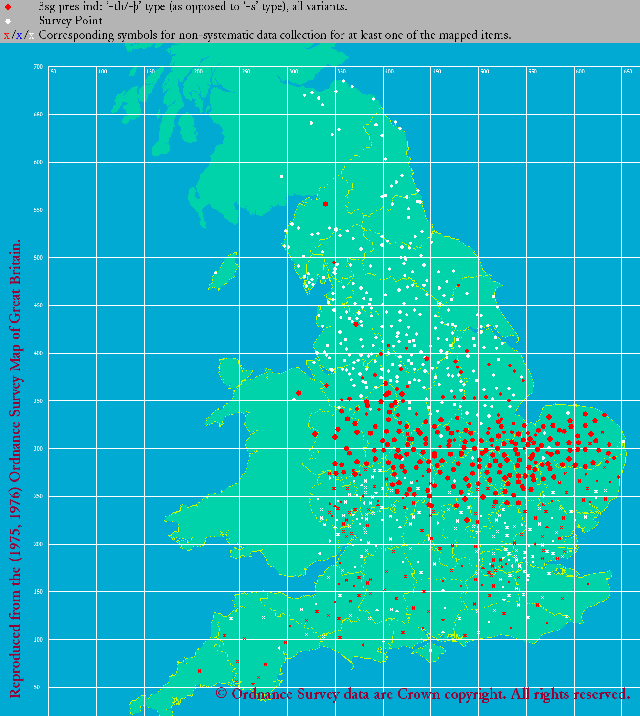

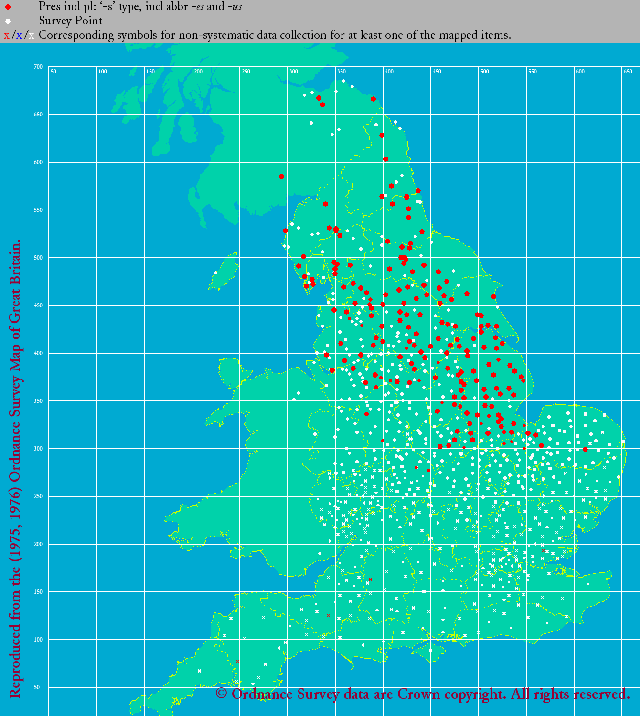

では次に後期中英語の分布に移る.eLALME では,語尾の種類ごとに別々の地図を作成した.まずは3単現から.

|

|

| eLALME: 3sp 's' | eLALME: 3sp 'th' |

前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,左図の通り -s が北部に,右図の通り -th が中部以南に分布しているのがわかる.複現については,-s, -th, -n, -e (or zero) の4種類について各々の地図を見てみよう.

|

|

| eLALME: pp 's' | eLALME: pp 'th' |

|

|

| eLALME: pp 'n' | eLALME: pp 'e' or zero |

こちらも前時代の分布をよく受け継いでおり,北部で -s (左上図),中部以南で -th (右上図)が優勢だが,中部で -n (左下図)が前時代よりも著しく拡張していることが見て取れる.全体的に,初期中英語と後期中英語の分布間で量的な差は見られるが,質的には大きな変化はないといってよいだろう. *

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-03-08 Sun

■ #2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][bible][shakespeare][schedule_of_language_change]

「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]) でみたように,17世紀中に3単現の屈折語尾が -th から -s へと置き換わっていった.今回は,その前の時代から進行していた置換の経緯を少し紹介しよう.

古英語後期より北部方言で行なわれていた3単現の -s を別にすれば,中英語の南部で -s が初めて現われたのは14世紀のロンドンのテキストにおいてである.しかし,当時はまだ稀だった.15世紀中に徐々に頻度を増したが,爆発的に増えたのは16--17世紀にかけてである.とりわけ口語を反映しているようなテキストにおいて,生起頻度が高まっていったようだ.-s は,およそ1600年までに標準となっていたと思われるが,16世紀のテキストには相当の揺れがみられるのも事実である.古い -th は母音を伴って -eth として音節を構成したが,-s は音節を構成しなかったため,両者は韻律上の目的で使い分けられた形跡がある (ex. that hateth thee and hates us all) .例えば,Shakespeare では散文ではほとんど -s が用いられているが,韻文では -th も生起する.とはいえ,両形の相対頻度は,韻律的要因や文体的要因以上に個人または作品の性格に依存することも多く,一概に論じることはできない.ただし,doth や hath など頻度の非常に高い語について,古形がしばらく優勢であり続け,-s 化が大幅に遅れたということは,全体的な特徴の1つとして銘記したい.

Lass (162--65) は,置換のスケジュールについて次のように要約している.

In the earlier sixteenth century {-s} was probably informal, and {-th} neutral and/or elevated; by the 1580s {-s} was most likely the spoken norm, with {-eth} a metrical variant.

宇賀治 (217--18) により作家や作品別に見てみると,The Authorised Version (1611) や Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) には -s が見当たらないが,反対に Milton (1608--74) では doth と hath を別にすれば -th が見当たらない.Shakespeare では,Julius Caesar (1599) の分布に限ってみると,-s の生起比率が do と have ではそれぞれ 11.76%, 8.11% だが,それ以外の一般の動詞では 95.65% と圧倒している.

とりわけ16--17世紀の証拠に基づいた議論において注意すべきは,「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) で見たように,表記上 -th とあったとしても,それがすでに [s] と発音されていた可能性があるということである.

置換のスケジュールについては,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2015-03-03 Tue

■ #2136. 3単現の -s の生成文法による分析 [generative_grammar][syntax][agreement][3sp][verb][inflection][agreement][conjugation]

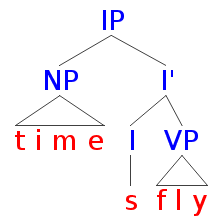

「#2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか?」 ([2015-02-07-1]) で,生成文法による分析を批判的に取り上げた.だが,それはなぜという問いには答えられていないという批判であり,共時的な分析として批判しているわけではない.むしろ,それは主語と動詞の一致 (agreement) を動詞の屈折によって標示する言語に一般的に適用できる,共時的にすぐれた分析だろう.Time flies. という単純な文に生成文法の統語分析を加えると,以下の構文木が得られる(ただし,生成文法でも立場によって機能範疇のラベルや細部の処理が異なる可能性はある).

最上部は文全体に相当する IP (=Inflectional Phrase) であり,主要部に I (=Inflection),指定部に主語となる NP (=Noun Phrase),補部に述語動詞となる VP (=Verb Phrase) をもつ.NP の time と I の s は統率 (government) し合う関係にあるといわれ,この統率関係が上述の一致と深く関連している.NP の time には,[+ 3RD PERSON] と [+ SINGULAR] という素性が付与されており,I に内包される [+ PRESENT] と共鳴して,s という屈折辞が選ばれる.

上の図ではそこまでしか描かれていないが,このあと接辞移動 (affix-hopping) という規則が適用されて,s が VP の fly の末尾に移動し,最後に音韻部門で音形が調えられて time flies という実現形が得られるとされる.要するに,統率関係にある NP と I のもとで,人称・数・時制の各素性の値が照合され,すべて一致すると屈折辞 s が選択されるというルールだ(実際には,3・単・現のほか,直説法であることも必須条件だが,ここでは省略する).このルールを1つ決めておくと,既存の他の統語規則も活用して,関連する応用的な文である否定文 "Time doesn't fly." や疑問文 "Does time fly?" なども正しく生成することができるようになる.

この分析は標準現代英語の3単現の -s にまつわる統語と形態を一貫したやりかたで説明できるという利点はあるが,なぜそのような現象があるのかということは説明しない.生成文法は「何」や「どのように」の問いに答えるのは得意だが,「なぜ」の問いに答えるには,やはり歴史的な視点を採用するほかないだろう.

2015-02-27 Fri

■ #2132. ら抜き言葉,ar 抜き言葉,eru 付け言葉 [japanese][lexical_diffusion][language_change][verb][conjugation][ranuki]

現代日本語に生じている言語変化のなかで,メディアなどでも大きく取り上げられて最もよく知られているものに「ら抜き言葉」がある.ら抜き言葉について本ブログでは「#1864. ら抜き言葉と頻度効果」 ([2014-06-04-1]) で取り上げた程度だが,研究も盛んで,変化の起源や過程について多くのことが分かってきている.この問題について重要な洞察を与えてくれる読みやすい議論としては,井上に勝るものはない.

ら抜き言葉とは,一段動詞の可能形について,伝統的な標準形である「見られる」「起きられる」から「ら」が抜け落ちて「見れる」「起きれる」となってきている現象を指す.確かに「ら」が抜けているように見えるが,そうではないという考え方もある.この変化を音素表記で記すと mirareru → mireru,okirareru → okireru となり,脱落しているのは mi(ra)reru, oki(ra)reru のように ra であるとともみなすことも確かにできるが,一方 mir(ar)eru, okir(ar)eru のように ar が脱落しているとみることもできる.実際,「ar 抜き言葉」という見方は,一段動詞以外の可能形も含めて説明するのに都合がよい.五段動詞の「読む」の標準的な可能形は,古い「読まれる」 (yomareru) に対して「読める」 (yomeru) だが,ここでは「ら」が脱落しているとは言えないものの,yom(ar)eru のように ar 抜きが起こっているとは言える.厳密な意味で可能形から「ら」が抜けるのは,一段動詞,ラ行五段動詞,カ行変格動詞のみであり,その他についてはら抜き言葉という呼称は適切ではないのである.つまり,ar 抜き言葉と呼んでおけば,一段動詞であろうが五段動詞であろうが,動詞の活用型にかかわらず,伝統的な可能形に対して現在広く使われるようになっている新しい可能形の音形を,一貫して正しく記述できることになる.

このように,ar 抜きという分析は発展途上にある可能動詞の形態を一貫して記述することができるが,さらに単純な記述法がある.可能動詞の終止形は,もととなる動詞の語幹への eru 付けであると表現すればよい.動詞の活用型に限らず,「見る」 (mir-u) から「見れる」 (mir-eru),「起きる」 (okir-u) から「起きれる」 (okir-eru),「読む」 (yom-u) から「読める」 (yom-eru),「取る」 (tor-u) から「取れる」 (tor-eru) を一貫して導き出せる(ただし変格動詞は「来る」 (kur-u) に対して「来れる」 (kor-eru) のように語幹が交替することに注意).aru 抜きの分析は,「見られる」「起きられる」「読まれる」「取られる」「来られる」など伝統的な可能形を経由しないと新しい可能形を導き出せないが,eru 付けの分析は,非可能形のもとの動詞の終止形を基点として新しい可能形を導き出せるという利点がある(井上,pp. 22--23).

現在進行中の言語変化にはよくあることだが,ら抜き言葉も起源は案外と古い.東京では昭和初期から記録があり,おそらく変化が開始したのは大正期だろう.東京以外に目を移せば,東海地方では明治期から用いられていた.ら抜き言葉の方言分布から伝播の経路を読み解くと,中部地方や中国地方などの周辺部で早く始まり,それが各々関東地方や近畿地方などの中心部へ流れ込んできたもののようだ.さらに長いスパンで考えると,ら抜き言葉化は一段動詞のラ行五段動詞化という潮流の一翼を担っており,それ自体は千年も続いている動詞の活用型の簡略化のなかに位置づけられる.

・ 井上 史雄 『日本語ウォッチング』 岩波書店〈岩波新書〉,1999年.

2015-02-25 Wed

■ #2130. "I wonder," said John, "whether I can borrow your bicycle." [syntax][word_order][verb][agreement]

主語と動詞が倒置される例に,標題のような直接引用を導く said John などの表現がある.引用される文句の後または中間に来るときに,現在形あるいは過去形の伝達動詞が主語に前置される場合である.このような位置で I said, I replied, I thought などの通常の語順を取る場合もあるが,quoth の場合には倒置されるのが規則である.細江 (163--64) から例を挙げよう.

・ "Can I have a light, sir?" said I.---Stevenson.

・ "My very dog," sighed poor Rip, "has forgotten me!"---Irving.

・ But where, thought I, is the crew?---Irving.

・ There was no getting away from these verities, thought Constance.---Bennett.

・ "The swine turned Normans to my comfort!" quoth Gurth.---Scott.

・ Quoth I: "But have you no prison at all now?"---William Morris.

・ "Well," quoth I, "I have always been told that a woman is as old as she looks."---ibid.

引用される文句の後または中間の位置では quoth を除き,SVもVSもいずれも可能ということだが,主語が代名詞か名詞によっても分布は異なる.Quirk et al. (1022) によると,主語が名詞の場合の John said や said John はいずれも普通だが,主語が代名詞の場合は he said が普通で,said he は珍しいか古風だという.古い英語では said he などもごく普通に見られたが,現代までに分布を狭めたらしい.

一方,引用される文句の前に置かれるときに通常倒置は起こらない.しかし,特殊な環境においては起こりうる.細江 (165fn) によると,

もっともややこっけい味を帯びた文または人の発言によって事件の推移の急であるときには,Said she, "Tom, it was middling warm in school, warn't it?"---Mark Twain; Said I: "How do you manage with politics?"---William Morris のようなものもある.すべて,上記の場合にも後に来るものに重点がある.したがって主語が名詞である場合に転置が多く,代名詞のときには常位置が多い.ゆえに代名詞の主語が動詞よりも後に来たときには,特にそれが強く示されているものと見てよい.反対に主語が名詞で,それが動詞より前にあったら,動詞に重点がおかれているものと解すべきである.Cp. "Mr. Sherlock Holms, I believe," said she.---Doyle (これはよもや知るまいと思っていた女が,ちゃんと知っていたから,she が強調された場合); Barbara looked enchanting to-day, Basil thought.---Alfred Noyes (これは Basil の思いに注意が向けられている場合).

また,journalistic writing でも,引用文句の前でときにVSとなる場合がある (ex. "Declared tall, nineteen-year-old Napier: 'The show will go on'." (Quirk et al. 1024fn)) .

ほかに変わったところでは,くだけた会話において行儀の悪い言い返しとして,-s 語尾をつけた says you や says he などが聞かれることがある.A: I'm going to win this game., B: Says you! の如くであり,ここでBが意味しているのは "That's what you say." ほどである.

通時的な関心としては,被引用文句の後や中間において said he のタイプが減少してきた経緯と理由が気になる.歴史統語論や歴史語用論の観点からある程度研究されているのではないかと思われるが,今後調べてみたい.

以下に,直接引用を導く典型的な伝達動詞を一覧していおこう (Quirk et al. 1024)

add, admit, announce, answer, argue, assert, ask, beg, boast, claim, comment, conclude, confess, cry (out), declare, exclaim, explain, insist, maintain, note, object, observe, order, promise, protest, recall, remark, repeat, reply, report, say, shout (out), state, tell, think, urge, warn, whisper, wonder, write

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2015-02-12 Thu

■ #2117. playwright [etymology][metathesis][verb][suffix]

英語の姓に Wright さんは普通にみられるが,これは「職人」の意味である.普通名詞として単体で wright (職人)として用いられることは今はほとんどないが,様々な種類の職人を表すのに複合語の一部として用いられることはある.比較的よくみるのは playwright (劇作家)である.これは戯曲を書く (write) 人ではなく,職人的に作り出す人 (wright) である.もし write (書く)に関係しているのであれば,行為者を表す接尾辞 (agentive suffix) をつけて writer (書き手)となるはずだろう.ほかにも arkwright, boatwright, cartwright, comedywright, housewright, millwright, novelwright, ploughwright, shipwright, timberwright, waggonwright, wainwright, wheelwright, woodwright などがある.

この wright は起源を遡ると,動詞 work に関係する.この動詞の古英語形 wyrcan は「行う;作る;生み出す」など広い意味で用いられ,その語幹に語尾が付加された wyrhta (< wyrcta) が「職人」として使われた.この語形成は他のゲルマン諸語にも見られ,起源は相応して古いものと思われる.wyrhta からは,第1母音と r とが音位転換 (metathesis) した wryhta が異形として生まれ,後に <a> で表される語末母音が水平化・消失するに及んで,現代につらなる wright の母型ができあがった.音位転換は,work の古い過去・過去分詞形 wrought にも見られる.

MED の wrigt(e (n.(1)) によると,中英語で,この語が以下のようなあまたの綴字(そしておそらくは発音)で実現されていたことがうかがえる.

wright(e (n.(1)) Also wrigt(e, wrigth(e, wrigh, wriȝt(e, wriȝth(e, wriht(e, writ(e, writh(e, writht, wreth(e, (N) wreght, (SWM) wrouhte, whrouhte & (chiefly early) wricht(e, (early) wirhte, (chiefly SW or SWM) wruhte, wruchte, wurhte, wurhta, wurhtæ, wuruhte & (in names) wrightte, wrighthe, wrig, wri(h)tte, wrihgte, wrichgte, wrich(e, wrict(e, wricth(e, wrick, wristh, wrieth, wreghte, wreȝte, wrehte, wrechte, wrecthe, wreit, wreitche, wreut(t)e, wroghte, wrozte, wrouȝte, wrughte, wrushte, wrh(i)te, wirgh, wirchte, wiche, wergh(t)e, werhte, wereste, worght(t)e, worichte, worithte, wort, worth, whrighte, whrit, whreihte, whergte, right, rith; pl. wrightes, etc. & wriȝttis, writtis, (NEM) whrightes & (early) wrihten, wirhten, (SWM) wrohtes, wurhten, (early gen.) wurhtena, (early dat.) wurhtan & (gen. in place names) wrightin(g)-, wri(c)tin-, wrichting-, wrstinc-, uritting-.

また,中英語では castlewright, feltwright, glasswright などに相当する現代には見られない職人名や,battlewright (戦士),Latinwright (ラテン語学者)などに相当する変わり種も見られた.複合語の人名も,現代まで伝わっているものもいくつかあるが, Basketwricte, Bordwricht, Bowwrighth, Briggwricht, Cartewrychgte, Chesewricte, Waynwryche, Wycchewrichte など幅広く存在した.

中英語までは wright は複合語要素として生産性を保っていたようだが,その後は次第に衰えていき,現在では数えるほどしか残っていない.この衰退の原因として,中英語以降にフランス語やラテン語から新たな職業・職人名詞が流入してきたこと,-er や -ist を含む種々の行為者接尾辞による語形成が活発化してきたことが疑われるが,未調査である.

2015-02-07 Sat

■ #2112. なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか? [verb][inflection][agreement][conjugation][paradigm][morphology][3sp][3pp][sobokunagimon]

標題は,英語学習者が一度は抱くはずの素朴な疑問の代表格である.現代英語では動詞の3人称単数現在形として語幹に接尾辞 -(e)s を付すのが規則となっている.(1) 主語が3人称であり,(2) 主語が単数であり,(3) 時制が現在であるという3つの条件がすべて揃ったときにのみ接尾辞を付加するという厳しい規則なので,英語学習者にとって習得しにくい(厳密には (4) 直説法であるという条件も必要).私自身も,英語で話したり書いたりする際には,とりわけ主語と動詞が離れた場合などに,規則で要求される一致をうっかり忘れてしまう.3単現の -s とは何なのか,何のために存在するのか,と学習者が不思議に思うのは極めて自然である.

現代英語における3単現の -s の問題は奥の深い問題だと思っている.共時的な観点からは,動詞の一致という広範な現象の一種として,種々の議論や分析がなされうる.形式主義の立場からは,例えば生成文法では InflP という機能範疇のもとで主語に相当する名詞句の素性と屈折辞との関係を記述することで,どのような場合に動詞に -s が付加されるかを形式化できる.しかし,これは条件を形式化したにすぎず,なぜ3単現のときに -s が付くのか,その理由を説明することはできない.

一方,機能主義の立場からは,-s の有無により,(1) 主語が3人称か1・2人称かの区別,(2) 主語が単数か複数かの区別,(3) 時制が現在か非現在かの区別を形態的に明示することができる,と論じられる.例えば,主語が John 1人を he で指すか,あるいは John and Mary 2人を they で指すかのいずれかであると予想される文脈において,主語代名詞部分が聞き取れなかったとしても,(現在時制という仮定で)動詞の語尾を注意深く聞き取ることができれば,正しい主語を「復元」できる.このような復元可能性がある限りにおいて,-s の有無は機能的ということができ,したがって3単現の -s という規則も機能的であると論じることができる.

しかし,ここでも3単現の -s の「なぜ」には答えられていない.復元可能性という機能を確保したいのであれば,特に3単現に -s をつけるという方法ではなく,他にも様々な方法が考えられるはずだ.なぜ3単現の -p とか -g ではないのか,なぜ3複現の -s ではないのか,なぜ3単過の -s ではないのか,等々.あるいは,これらの可能性をすべて組み合わせた適当な動詞のパラダイムでも,同じように用を足せそうだ.つまり,上記の機能主義的な説明は,3単現の -s をもつ現代英語のパラダイムに限らず,同じように用を足せる他のパラダイムにも通用してしまうということである.結局,機能主義的な説明は,なぜ英語がよりによって3単現の -s をもつパラダイムを有しているのかを説明しない.

形式的であれ機能的であれ,共時的な観点からの議論は,3単現の -s に関する説明を与えようとはしているが,せいぜい説明の一部をなしているにすぎず,本質的な問いには答えられてない.だが,通時的な観点からみれば,「なぜ」への答えはずっと明瞭である.

通時的な解説に入る前に,標題の発問の前提をもう一度整理しよう.「なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか」という疑問の前提には,「なぜ3単現というポジションでのみ余計な語尾がつかなければならないのか」という意識がある.他のポジションでは裸のままでよいのに,なぜ3単現に限って面倒なことをしなければならないのか,と.ところが,通時的な視点からの問題意識は正反対である.通時的には,3単現で -s がつくことは,ほとんど説明を要さない.コメントすべきことは多くないのである.むしろ,問うべきは「なぜ3単現以外では何もつかなくなってしまったのか」である.

では,謎解きのとっかかりとして,古英語の動詞 lufian (to love) の直説法現在の屈折表を掲げよう.

| lufian (to love) | Singular | Plural |

|---|---|---|

| 1st person | lufie | lufiaþ |

| 2nd person | lufast | lufiaþ |

| 3rd person | lufaþ | lufiaþ |

この屈折表から分かるように,古英語では3単現に限らず,1単現,2単現,1複現,2複現,3複現でも何らかの語尾が付いていた.現代英語の観点からは,3単現のみに語尾が付くために3単現という条件を特別視してしまうが,古英語では(それ以前の時代もそうだし,中英語にも初期近代英語にも部分的にそう言えるが)それぞれの人称・数・時制の組み合わせが同程度に「特別」であり,いずれにも決められた語尾が付かなければならなかった.言い換えれば,3単現だけが現在のように浮いたポジションだったわけではない.

しかし,古英語の「すべてのポジションが特別」ともいえるこのパラダイムは,中英語から近代英語にかけて大きく変容する.古英語末期以降,屈折語尾が置かれるような無強勢音節において,音が弱化し,ついには消失するという大きな音変化の潮流が進行した.上記の lufian の例でいえば,1単現の lufie の語尾は弱化の餌食となり,中英語では明確な語末母音をもたない love となった.不定詞 lufian 自体も,同じく語末の子音と母音が弱化・消失し,結局「原形」 love へと発展した.一方,いずれの人称でも共通の古英語の複数形 lufiaþ は,屈折語尾における母音の弱化・消失の結果,3単現 lufaþ と形態的に融合してしまったことも関係してか,とりわけ中英語の中部方言で,接続法現在のパラダイムに由来する語尾に n をとる loven という形態を採用した.ところが,この n 語尾自体が弱化・消失しやすかったため,中英語末期までにはおよそ消滅し,結局 love へと落ち着いた.2単現の lufast については,屈折語尾として消失に抵抗力のある子音を2つもっており,本来であればほぼそのままの形で現代英語まで生き残るはずだった.ところが,2単現に対応する主語代名詞 thou が,おそらく社会語用論的な要因で存在意義を失い,その立場を you へと明け渡していくに及んで,-ast の屈折語尾自体も生じる機会を失い,廃用となった.2単現の屈折語尾は,2複現に対応する you と同じ振る舞いをすることになったため,このポジションへも love が侵入した.

残るは3単現の lufaþ である.語尾に消失しにくい子音をもっていたために,中英語まではほぼそのままに保たれた.中英語期に北部方言に由来する -s が勢力を拡げ,元来の -þ を置き換えるという変化があったものの,結果としての -s も消失しにくい安定した子音だったため,これが現代英語まで生き残った.他のポジションの屈折語尾が音声的な弱化・消失の餌食となったり,他の主要な語尾に置換されていくなどして,ついには消え去ったのに対し,3単現の -s は音声的に強固で安定していたという理由で,運良く(?)たまたま今まで生き残ったのである.3単現の -s は直説法現在の屈折パラダイムにおける最後の生き残りといえる.

改めて述べるが,通時的な視点からの問題意識は「なぜ3単現の -s がつくのか」ではなく「なぜ3単現以外では何もつかなくなってしまったのか」である.この「なぜ」の答えの概略は上で述べてきたが,実際には個々のポジションについてもっと複雑な経緯がある.英語史では,屈折語尾の水平化 (levelling of inflection) として知られる大規模な過程の一端として,重要かつ複雑な問題である.

3単現の -s 関連の諸問題については 3sp の各記事を,関連する3複現の -s という英語史上の問題については 3pp の各記事を参照されたい.

(後記 2017/03/15(Wed):関連して,研究社のウェブサイト上の記事として「なぜ3単現に -s を付けるのか? ――変種という視点から」を書いていますので,ご参照ください.)

2015-01-10 Sat

■ #2084. drink--drank--drunk と win--won--won [verb][conjugation][inflection][vowel][oe][homorganic_lengthening][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の不規則活用を示す動詞,特に語幹の母音交替 ( Ablaut or gradation ) により過去・過去分詞形を作る動詞の多くは,歴史的な強変化動詞に由来する.古英語では現代英語よりも多くの動詞が強変化動詞に属しており,その大半が現代までに弱変化(規則活用)へ移行するか,あるいは廃語となった.動詞のいわゆる強弱移行の歴史については,「#178. 動詞の規則活用化の略歴」 ([2009-10-22-1]) ,「#527. 不規則変化動詞の規則化の速度は頻度指標の2乗に反比例する?」 ([2010-10-06-1]) ,「#528. 次に規則化する動詞は wed !?」 ([2010-10-07-1]),「#764. 現代英語動詞活用の3つの分類法」 ([2011-05-31-1]),「#1287. 動詞の強弱移行と頻度」 ([2012-11-04-1]) などの記事を参照されたい.

さて,現代英語にまで生きながらえた強変化動詞は,活用の仕方によって標記の drink--drank--drunk のようなABC型や win--won--won のようなABB型など,いくつかの種類に区分されるが,これらは近代英語期以後の標準英語において確立したものと考えてよい.「#492. 近代英語期の強変化動詞過去形の揺れ」 ([2010-09-01-1]) でみたように,近代ではまだ過去形や過去分詞形の母音が揺れを示すものが少なくなかったし,現在でも方言を含む非標準変種では異なる母音が用いられたりする.

drink と win の活用タイプの違いや近代英語期に見られる揺れの起源は,古英語の強変化動詞には第1過去(「単数過去」とも)と第2過去(「複数過去」とも)の2種類が区別されていた事実にある.「#42. 古英語には過去形の語幹が二種類あった」 ([2009-06-09-1]) で述べたように,各動詞は主語の数と人称に応じて2つの異なる過去形をもっていた.drink でいえば,不定形 -- 第1過去形 -- 第2過去形 -- 過去分詞形の順に,drincan -- dranc -- druncon -- druncen のように活用し,win については winnan -- wann -- wunnon -- wunnen と活用した(これを活用主要形 (principal parts) と呼ぶ).ところが,中英語以後,屈折体系全体の簡略化の潮流に伴い,これらの動詞の過去形は2種類の形態を区別する機会を減らしていった.かつての第1過去形か第2過去形のうちいずれかが優勢となり徐々に唯一の過去形として機能していくことになったが,この過程は想像される以上に複雑であり,近代英語期までに形態が定着せず,激しい揺れを示したり方言差や個人差の著しい動詞も多かった.drink はたまたま第1過去 dranc に由来する形態が標準英語の過去形として定着することになり,win についてはたまたま第2過去 wunnan の形態(後に won と綴られ /wʌn/ と発音される)に由来する形態が採用されたということである.

第1過去形か第2過去形のいずれが採用されることになるかを決定づける要因は特定できない.drincan と winnan の属する強変化第3類の他の動詞について調べてみると,drinkcan のように後に第1過去形が採用されたものには hringan, scrincan, sincan, singan, springan, swimman があり,winnan のように第2過去形が採られたものには clingan, spinnan, stingan, wringan がある.しかし,非標準変種では過去形に別の母音をもつ形態が用いられるケースも少なくない.例えば,sing の過去形は標準変種では sang だが,非標準変種で sung が用いられることもある.また,spin の過去形も標準変種では spun だが,それ以外の変種では span もありうる,等々(岩崎,p. 76).

なお,bindan, findan, grindan, windan も強変化第3類の動詞で,いずれも後に第2過去形が採用されたタイプである (ex. bound, found, ground, wound) .この母音は,初期中英語で生じた同器性長化 (homorganic_lengthening) により長くなり,さらに後に大母音推移 (gvs) により2重母音化した /aʊ/ をもつに至っている点で,winnan のタイプとは少々異なる音韻的経緯を辿った.

・ 岩崎 春雄 『英語史』第3版,慶應義塾大学通信教育部,2013年.

2015-01-09 Fri

■ #2083. She'll make a good wife. の構文 [syntax][verb]

現代英語で半ば化石化した構文として知られているものに,標記の構文がある.この make の意味・機能は become に近く,学校文法でいえば主格補語を要求する不完全自動詞であるといわれ,その構文は5文型の枠組みいえば SVC とされる.一方,「彼にとって」の意味を加えて She'll make him a good wife. と表現することもでき,him ≠ a good wife であるから,この構文は SVOO と解釈できる.ここで両構文が関係しているものと解するならば,もとの She'll make a good wife. はむしろ SVO 構文と分析したくなる.このような事情で,標記の構文は SVC とも SVO ともつかない,両方の特性を兼ね備えた不思議な構文ということになる.解釈の仕方は,統語理論によってもまちまちである.

この構文はときに再帰代名詞の省略と説明されることがあるが,その説明には,共時的にも通時的にも確たる裏付けがない.共時的には,She'll make herself a good wife. は文法上もちろん可能だが,標記の構文の代用として現われることはあまりない.また,通時的にも,代名詞を含む構文が原型としてあり,そこから再帰代名詞が省略されてこの構文ができたという歴史的過程を確認することはできない.むしろ,歴史的には make の「作る」という原義と目的語を要求する原用法から発展してきた構文の1つにすぎない.OED (語義24)によると,この構文で用いられる make の語義は,"Of a person: to become by development or training. Also, with object a noun modified by good, bad, or other adjective of praise or the contrary: to perform well (ill, etc.) the part or function of." と記述される.主語の表わす人が発展や訓練を経てあるものへと化ける,というほどの意味を表わし,前者に後者となるための素質が備わっていることが含意されている点で become とは異なる.素材と産物の関係とでもいおうか.この用法が,素材と産物の関係を示す make の他の用法からの派生物であることは,現代英語の次のような例から分かる.

・ Northern Spies make the best apple pie.

・ The platycodon makes a fine pot plant for a cool greenhouse.

・ The Morello Cherry, and other deepe coloured pleasant Cherries, no doubt would make a speciall good wine.

・ Hydrogen and oxygen make water.

・ The clothes don't make the gentleman.

このような素材と産物を表現する make の用法は,OED の例文をみる限りおよそ中英語に起源をもつようだ.もっとも語義は連続体なので,ものによっては古英語に遡るともいえる.OED の語義24に関する限り,その初出例文は中英語末期の "a1470 Malory Morte Darthur (Winch. Coll. 13) (1990) I. 295, I undirtake he is a vylayne borne, and never woll make man." であり,案外と新しい.近現代英語からの例文をいくつか挙げておこう.

・ 1572 H. Middlemore in H. Ellis Orig. Lett. Eng. Hist. (1827) 2nd Ser. III. 8, I think he [sc. the Duke of Anjou] will make as rare a prince as any is in Christendome.[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

・ a1616 Shakespeare Henry VI, Pt. 1 (1623) iv. vii. 44 Doubtlesse he would haue made a noble Knight.

・ 1741 Pope Thoughts on Var. Subj. in Wks. II. 311 For a King to make an amiable character, he needs only to be a man of common honesty, well advised.

・ 1870 E. Peacock Ralf Skirlaugh III. 25 As the times then went, Mr. Earl made a very fair pastor.

・ 1934 H. Roth Call it Sleep i. ix. 63 My, what a tyrant you'll make when you're married!

2014-07-27 Sun

■ #1917. numb [etymology][participle][silent_letter][verb][old_norse][loan_word][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

古ノルド語によって置き換えられた幾多の古英語の単語のうち,とりわけ重要なものの1つに動詞 niman (to take) がある.古英語から中英語にかけて最も卑近な動詞の1つだったが,古英語後期に古ノルド語から入った同義語 taka (後の take)に置き換えられることになった.現代英語では「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]) の各種の語彙頻度表で見る限り,take は上位60位以内に入る超高頻度語である.このように日常的な意味を担当する語において本来語から借用語への移行が生じるほどの言語接触とはいかなる状況だったかについては様々な考察がなされてきたが,有力な見解によれば,古英語と古ノルド語が社会言語学的な上下関係にはなく,横並びの adstrata (傍層)をなしていたからだろうとされている.実際,中英語でも nimen と tāken は互いに長い競合・併存関係を経験しており,決して短期間で前者が後者に置換されたわけではない.niman は16世紀に一時衰退したが,1600年以降再び復活するなどの振る舞いを示し,17世紀を通じて一般的に用いられた.しかし,結果としては niman 系統は現在までに,方言を除いて事実上廃用となり,take が niman のほぼすべての用法を置換して,現在に至っている.両語の競合関係については,Rynell に詳しく記述されている.

古英語 niman は,ゲルマン祖語の *neman に遡り,同根語としてはオランダ語 nemen, ドイツ語 nehmen, ゴート語 niman のほか,古ノルド語そのものにも nema がある.さらに遡れば,印欧祖語 *nem- (to distribute) にたどりつき,ここからギリシア語 némein (to distribute) を経た nemesis (ネメシス;ギリシア神話の応報天罰の女神)が英語に入っている.

古英語 niman は強変化4類の動詞で,niman -- nam -- nōmon -- numen のように活用した.方言によって,またパラダイム内の類推により,各スロットに異なる母音が現われたが,いずれも初期近代英語期までには弱変化化した.

このように,niman は現代標準英語では痕跡をほぼ残していないといってよいが,1つだけ重要な生きた化石がある.過去分詞 numen に由来する形容詞 numb (かじかんだ;無感覚になった;しびれた) /nʌm/ である."taken, seized, overcome" ほどの意味から「感覚を失った」の語義を獲得したものと考えられる.初出は,a1400の Cursor Mundi (Frf 14) の13821行に nomin の異形として現われる ("xxviij 3ere in bande I lay nomme baþ fote & hande.") .非語源的な語末の <b> の挿入は16世紀からで,crumb, limb, thumb などと比較される.無音の <b> の挿入については,「#34. thumb の綴りと発音」 ([2009-06-01-1]), 「#724. thumb の綴りと発音 (2)」 ([2011-04-21-1]), 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Rynell, Alarik. The Rivalry of Scandinavian and Native Synonyms in Middle English Especially taken and nimen. Lund: Håkan Ohlssons, 1948.

2014-06-29 Sun

■ #1889. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s (2) [verb][inflection][aave][nptr][3pp][3sp]

「#1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s」 ([2014-05-21-1]) に引き続いての話題.AAVE で3単現の -s が脱落する傾向について「#1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題」 ([2014-06-25-1]) でも述べたが,この脱落傾向を記述することはまったく単純ではない.AAVE といっても一枚岩ではなく,地域によって異なるし,何よりも個人差が大きいといわれる.脱落するかしないかのパラメータは複数存在し,それぞれの効き具合も変異する.

例えば,Schneider (100) は,いくつかの先行研究を参照して3単現の -s の脱落のパーセンテージをまとめている.Harlem の青年集団の調査で42--100% (平均すると 63%),Detroit の下流労働者階級の調査で71.4%,5歳児の調査で72.5%,Oakland の下流階級の女性の調査で57.7%,Washington, D. C. の子供の調査で84%,Washington, D. C. の下流階級の調査で65.3%,下流階級の説教師の調査で17--78%,Maryland の学生の調査で83.3%などである.-s の脱落が支配的であることは確かだが,一方で,大雑把にいって3回に1回は -s が現われているということでもあり,脱落が規則的であるということはできない.

AAVE における(3単現の -s のみならず)動詞現在形の -s に関する従来の研究では,様々な(社会)言語学的なパラメータが提起されてきた.標準英語に見られるような数・人称の条件はもとより,be 動詞の is が複数に用いられる現象との関与,標準英語の規範への遵守の程度,dialect mixture (「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) を参照),イギリス諸方言の歴史的な影響など,様々である.

様々なパラメータのなかで Bailey et al. がとりわけ目を付けたのが,主語が代名詞 (PRO) か名詞句 (NP) かの区別である.先行研究では,Appalachian English, Alabama White English, Samaná, Scotch-Irish English, black and white folk speech in Texas など,AAVE に限らず南部の白人変種やイギリス変種でも,この基準が作用していること,すなわち現在形で NP 主語が PRO 主語よりも -s を好んで選択することが指摘されていた.この傾向は,「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) で触れた,いわゆる "Northern Personal Pronoun Rule" ("Northern Present Tense Rule") の効果と類似している.Bailey et al. は,この "NP/PRO constraint" が 1472--88年にロンドンの羊毛商一家が残した書簡集 the Cely Letters や17--18世紀のイギリス人航海士たちの用いた "Ship English" にみられることを指摘したうえで,量的な比較調査を通じて,同じ効果が現代の AAVE の諸変種にも受け継がれていることを示唆している.Bailey et al. (298) は,"NP/PRO constraint" だけできれいに記述できるほど単純な問題ではないと強調しながらも,望みをもって次のように締めくくっている.

By examining data from EME and looking at parallels in present-day black and white vernaculars, we have shown that the NP/PRO constraint is a powerful one that has affected English for quite some time and that currently affects a wide range of processes. Although it is important to stress that this constraint does not account for all of the variation in the present tense verb paradigms of the black and white vernaculars in the South (for instance, -s used to mark historical present), it does play a major role in a number of previously unconnected phenomena.

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "The Origin of the Verbal -s in Black English." American Speech 58 (1983): 99--113.

・ Bailey, Guy, Natalie Maynor, and Patricia Cukor-Avila. "Variation in Subject-Verb Concord in Early Modern English." Language Variation and Change 1 (1989): 285--300.

2014-05-31 Sat

■ #1860. 原形と同じ形の過去分詞 [conversion][adjective][participle][verb]

現代英語には affect, attract, celebrate, dedicate, indicate, relate などロマンス系の動詞が多く存在する.語幹末尾に /t/ をもつこれらの語形はラテン語の過去分詞形(典型的な語尾は -ātus)に由来するが,英語へ取り込まれる際には /t/ を含めた全体が動詞語幹と解釈された.この背景には,形容詞から動詞への品詞転換 (conversion) が英語において広く生産的であったことが関与していると言われる.この経緯については,「#438. 形容詞の比較級から動詞への転換」 ([2010-07-09-1]) や「#1383. ラテン単語を英語化する形態規則」 ([2013-02-08-1]) の記事で簡単に触れた通りである.

さて,このような語群の一部には,現代英語において古風な用法ではあるが,原形がそのまま過去分詞として用いられるものがある.例えば,create, dedicate, frustrate は,このままの形態で,規則的な過去分詞形 created, dedicated, frustrated と同等の過去分詞として用いられることがある.現代の用法としては限定的だが,中英語や初期近代英語では,これらの動詞において原形と同形の過去分詞形が,規則的な -ed 形と並んで広く行われていた.荒木・宇賀治 (206--08) は,中英語における -ed 形とゼロ形の相対頻度を示した Reuter (45, 89) による以下のデータを掲載しながら,語幹が /t/ で終わる動詞についてはむしろゼロ形のほうが好まれたことを指摘している.

| /t/ で終わるもの | /t/ で終わらないもの | ||||

| {-ed} | {-ø} | {-ed} | {-ø} | ||

| 13--14世紀 | Chaucer | 55 | 58 | 19 | 9 |

| Wyclif | 17 | 26 | 3 | 0 | |

| Trevisa | 15 | 62 | 2 | 1 | |

| Gower | 3 | 29 | 2 | 9 | |

| 15世紀 | Lydgate | 13 | 116 | 7 | 1 |

| Tr. Palladius | 5 | 70 | 3 | 7 | |

| Tr. Higden | 極く少数 | ほとんど | すべて | 0 | |

| Tr. Delm | 1 | 44 | 4 | 0 | |

| Capgrave | 9 | 54 | 2 | 0 | |

| Ripley | 0 | 48 | 0 | 0 | |

| Henryson | 3 | 48 | 0 | 0 | |

| Monk of Evesh | 5 | 29 | 1 | 0 | |

| Bk. St. Albans | 11 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

| Caxton | 165 | 118 | すべて | 0 | |

中英語において /t/ で終わるゼロ形の過去分詞が好まれた理由として,荒木・宇賀治 (207) は「英語本来の弱屈折動詞で,語幹が /t/ (および /d/)で終り,不定詞にゆるみ母音をもつものは,ME期に過去・過去分詞形と同形になったことの影響によるものであろう」と述べている.関連して,「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1]) と「#1858. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc. (2)」 ([2014-05-29-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

中英語でゼロ形が好まれた上述の傾向は,しかし,15世紀末には退潮を示していた.その頃までには,/t/ で終わる語についても規則的な -ed 形が一般的になっており,ゼロ形は衰えていた.その後もゼロ形の衰退はゆっくりではあるが着実に進行し,18世紀にはほとんどの動詞において廃用に帰した.現在まで残存した少数のゼロ形についても,過去分詞の異形というよりは純粋な形容詞として意識されている.残存した例としては上述の3語のほか,confiscate, consecrate, distract, elect, infatuate, sophisticate などが含まれる.

・ 荒木 一雄,宇賀治 正朋 『英語史IIIA』 英語学大系第10巻,大修館書店,1984年.

・ Reuter, O. On the Development of English Verbs from Latin and French Past Participles. Commentationes Humanarum Literarum, VI. 6. Helsingfors: Centraltryckeriet, 1934.

2014-05-30 Fri

■ #1859. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s (5) [verb][conjugation][emode][paradigm][analogy][3pp][shakespeare][nptr][causation]

今回は,これまでにも 3pp の各記事で何度か扱ってきた話題の続き.すでに論じてきたように,動詞の直説法における3複現の -s の起源については,言語外的な北部方言影響説と,言語内的な3単現の -s からの類推説とが対立している.言語内的な類推説を唱えた初期の論者として,Smith がいる.Smith は Shakespeare の First Folio を対象として,3複現の -s の例を約100個みつけた.Smith は,その分布を示しながら北部からの影響説を強く否定し,内的な要因のみで十分に説明できると論断した.その趣旨は論文の結論部よくまとまっている (375--76) .

I. That, as an historical explanation of the construction discussed, the recourse to the theory of Northumbrian borrowing is both insufficient and unnecessary.

II. That these s-predicates are nothing more than the ordinary third singulars of the present indicative, which, by preponderance of usage, have caused a partial displacement of the distinctively plural forms, the same operation of analogy finding abundant illustrations in the popular speech of to-day.

III. That, in Shakespeare's time, the number and corresponding influence of the third singulars were far greater than now, inasmuch as compound subjects could be followed by singular predicates.

IV. That other apparent anomalies of concord to be found in Shakespeare's syntax,---anomalies that elude the reach of any theory that postulates borrowing,---may also be adequately explained on the principle of the DOMINANT THIRD SINGULAR.

要するに,Smith は,当時にも現在にも見られる3単現の -s の共時的な偏在性・優位性に訴えかけ,それが3複現の領域へ侵入したことは自然であると説いている.

しかし,Smith の議論には問題が多い.第1に,Shakespeare のみをもって初期近代英語を代表させることはできないということ.第2に,北部影響説において NPTR (Northern Present Tense Rule; 「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) を参照) がもっている重要性に十分な注意を払わずに,同説を排除していること(ただし,NPTR に関連する言及自体は p. 366 の脚注にあり).第3に,Smith に限らないが,北部影響説と類推説とを完全に対立させており,両者をともに有効とする見解の可能性を排除していること.

第1と第2の問題点については,Smith が100年以上前の古い研究であることも関係している.このような問題点を指摘できるのは,その後研究が進んできた証拠ともいえる.しかし,第3の点については,今なお顧慮されていない.北部影響説と類推説にはそれぞれの強みと弱みがあるが,両者が融和できないという理由はないように思われる.

「#1852. 中英語の方言における直説法現在形動詞の語尾と NPTR」 ([2014-05-23-1]) の記事でみたように McIntosh の研究は NPTR の地理的波及を示唆するし,一方で Smith の指摘する共時的で言語内的な要因もそれとして説得力がある.いずれの要因がより強く作用しているかという効き目の強さの問題はあるだろうが,いずれかの説明のみが正しいと前提することはできないのではないか.私の立場としては,「#1584. 言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因はどちらが重要か? (3)」 ([2013-08-28-1]) で論じたように,3複現の -s の問題についても言語変化の "multiple causation" を前提としたい.

・ Smith, C. Alphonso. "Shakespeare's Present Indicative S-Endings with Plural Subjects: A Study in the Grammar of the First Folio." Publications of the Modern Language Association 11 (1896): 363--76.

・ McIntosh, Angus. "Present Indicative Plural Forms in the Later Middle English of the North Midlands." Middle English Studies Presented to Norman Davis. Ed. Douglas Gray and E. G. Stanley. Oxford: OUP, 1983. 235--44.

2014-05-29 Thu

■ #1858. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc. (2) [verb][conjugation][degemination][inflection][phonetics][analogy][sobokunagimon]

「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1]) の記事に補足を加えたい.先の記事では,弱変化動詞の語幹の rhyme の構成が「緩み母音(短母音)+歯茎破裂音 /d, t/ 」である場合に {-ed} 接尾辞を付すと,古英語から中英語にかけて生じた音韻過程の結果,現在形,過去形,過去分詞形がすべて同形となってしまったと説明した.

しかし,実際のところ,上記の音韻過程による説明には若干の心許なさが残る.想定されている音韻過程のうち,脱重子音化 (degemination) は中英語での過程ととらえるにしても,それに先立つ連結母音の脱落や重子音化という過程は古英語の段階で生じたものと考えなければならない.ところが,先の記事で列挙した現代英語における無変化活用の動詞群のすべてがその起源を古英語にまで遡れるわけではない.例えば hit (< OE hyttan), knit (< OE cnyttan), shut (< OE scyttan), set (< OE settan), wed (< OE weddian) などは古英語に遡ることができても,cast, cost, cut, fit, hurt, put, split, spread などは初出が中英語以降の借用語あるいは造語である.また,元来 bid, burst, let, shed, slit などは強変化動詞であり後に弱変化化したものだが,そのタイミングと上記の想定される音韻過程のタイミングとがどのように関わり合っているかが分からない.古英語の弱変化動詞に確実には遡ることのできないこれらの動詞についても,set や shut の場合と同様に,音韻過程による説明を適用することはできるのだろうか.

むしろ,そのような動詞は,語幹の rhyme 構成が共通しているという点で,音韻史的に「正統な」無変化活用の動詞 set や shut と共時的に関連づけられ,類推作用 (analogy) によって無変化活用を採用するようになったのではないか.英語史において強変化動詞 → 弱変化動詞という流れ(強弱移行)は一般的であり,類推作用の最たる例としてしばしば言及されるが,一般の弱変化動詞 → 無変化活用動詞という類推作用の流れも,周辺的ではあれ,このように存在したと考えられるのではないか.無変化活用の動詞の少なくとも一部は,純粋な音韻変化の結果としてではなく,音韻形態論的な類推作用の結果として捉える必要があるように思われる.そのように考えていたところに,Jespersen (28) に同趣旨の記述を見つけ,勢いを得た.引用中の "this group" とは古英語に起源をもつ無変化活用の動詞群を指す.

Even verbs originally strong or reduplicative, or of foreign origin, have been drawn into this group: bid, burst, slit; let, shed; cost.

動詞の強弱移行については,「#178. 動詞の規則活用化の略歴」 ([2009-10-22-1]) ,「#527. 不規則変化動詞の規則化の速度は頻度指標の2乗に反比例する?」 ([2010-10-06-1]) ,「#528. 次に規則化する動詞は wed !?」 ([2010-10-07-1]),「#764. 現代英語動詞活用の3つの分類法」 ([2011-05-31-1]),「#1287. 動詞の強弱移行と頻度」 ([2012-11-04-1]) の各記事を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

2014-05-28 Wed

■ #1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][causation][suffix][inflection][phonotactics][3sp]

「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) と続けて3単現の -th → -s の変化について取り上げてきた.この変化をもたらした要因については諸説が唱えられている.また,「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]) で触れた通り,3複現においても平行的に -th → -s の変化が起こっていたらしい証拠があり,2つの問題は絡み合っているといえる.

北部方言では,古英語より直説法現在の人称語尾として -es が用いられており,中部・南部の -eþ とは一線を画していた.したがって,中英語以降,とりわけ初期近代英語での -th → -s の変化は北部方言からの影響だとする説が古くからある.一方で,いずれに方言においても確認された2単現の -es(t) の /s/ が3単現の語尾にも及んだのではないかとする,パラダイム内での類推説もある.その他,be 動詞の is の影響とする説,音韻変化説などもあるが,いずれも決定力を欠く.

諸説紛々とするなかで,Jespersen (17--18) は音韻論の観点から「効率」説を展開する.音素配列における「最小努力の法則」 ('law of least effort') の説と言い換えてもよいだろう.

In my view we have here an instance of 'Efficiency': s was in these frequent forms substituted for þ because it was more easily articulated in all kinds of combinations. If we look through the consonants found as the most important elements of flexions in a great many languages we shall see that t, d, n, s, r occur much more frequently than any other consonant: they have been instinctively preferred for that use on account of the ease with which they are joined to other sounds; now, as a matter of fact, þ represents, even to those familiar with the sound from their childhood, greater difficulty in immediate close connexion with other consonants than s. In ON, too, þ was discarded in the personal endings of the verb. If this is the reason we understand how s came to be in these forms substituted for th more or less sporadically and spontaneously in various parts of England in the ME period; it must have originated in colloquial speech, whence it was used here and there by some poets, while other writers in their style stuck to the traditional th (-eth, -ith, -yth), thus Caxton and prose writers until the 16th century.

言語の "Efficiency" とは言語の進歩 (progress) にも通じる.(妙な言い方だが)Jespersen だけに,実に Jespersen 的な説と言えるだろう.Jespersen 的とは何かについては,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を参照されたい.[s] と [θ] については,「#842. th-sound はまれな発音か」 ([2011-08-17-1]) と「#1248. s と th の調音・音響の差」 ([2012-09-26-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow