2015-09-18 Fri

■ #2335. parliament [parliament][etymology][etymological_respelling][history][med][spelling]

英国は,議会の国である.イングランド政治史は,国王と議会の勢力争いの歴史という見方が可能であり,parliament という単語のもつ意義は大きい.英語史においてもイングランド議会史は重要であり,このことは昨日の記事「#2334. 英語の復権と議会の発展」 ([2015-09-17-1]) で触れた通りである.また,「#880. いかにもイギリス英語,いかにもアメリカ英語の単語」 ([2011-09-24-1]) でみたように,parliament は,アメリカ英語に対してイギリス英語を特徴づけるキーワードの1つともなっている.

parliament という語は,Anglo-Norman の parlement, parliment, parliament や Old French, Middle French の parlement が,13世紀に英語へ借用されたものであり,原義は「話し合い,会議」である (cf. ModF parler (to speak); PDE parley) .これらの源となるラテン語では parlamentum という形が用いられたが,イギリスの文献のラテン語においては,しばしば parliamentum の綴字が行われていた.ただし,英語では借用当初は -e- などの綴字が一般的であり,-ia- の綴字が用いられるようになるのは15世紀である.MED の parlement(e (n.) により,多様な綴字を確認されたい.

-ia- 形の発展については,確かなことはわかっていないが,ラテン語の動詞語尾 -iare や,それに対応するフランス語の -ier の影響があったともされる (cf. post-classical L maniamentum (manyment), merciamentum (merciament)) .現代英語では,-ia- は発音上 /ə/ に対応することに注意.

parliament という語とその指示対象が歴史的役割を担い始めたのは,Henry III (在位 1216--72) の治世においてである.OALD8 の parliament の項の文化欄に以下の記述があった.この1語に,いかに英国史のエッセンスが詰まっていることか.

The word 'parliament' was first used in the 13th century, when Henry III held meetings with his noblemen to raise money from them for government and wars. Several kings found that they did not have enough money, and so they called together representatives from counties and towns in England to ask them to approve taxes. Over time, the noblemen became the House of Lords and the representatives became the House of Commons. The rise of political parties in the 18th century led to less control and involvement of the sovereign, leaving government in the hands of the cabinet led by the prime minister. Although the UK is still officially governed by Her Majesty's Government, the Queen does not have any real control over what happens in Parliament. Both the House of Lords and the House of Commons meet in the Palace of Westminster, also called the Houses of Parliament, in chambers with several rows of seats facing each other where members of the government sit on one side and members of the Opposition sit on the other. Each period of government, also called a parliament, lasts a maximum of five years and is divided into one-year periods called sessions.

2015-09-04 Fri

■ #2321. 綴字標準化の緩慢な潮流 [emode][spelling][standardisation][printing]

英語の綴字の標準化の潮流は,その端緒が見られる後期中英語から,初期近代英語を経て,1755年の Johnson の Dictionary 出版に至るまで,長々と続いた.中英語におけるフランス語使用の衰退という現象も同様だが,このように数世紀にわたって緩慢と続く歴史的過程というのは,どうも理解しにくい.15世紀ではどの段階なのか,17世紀ではどの辺りかなど,直感的にとらえることが難しいからだ.

私の理解は次の通りだ.14世紀後半,Chaucer の時代辺りに書き言葉標準の芽生えがみられた.15世紀に標準化の流れが緩やかに進んだが,世紀後半の印刷術の導入は,必ずしも一般に信じられているほど劇的に綴字の標準化を推進したわけではない.続く16世紀にかけても,標準化への潮流は緩やかにみられたが,それほど著しい「もがき」は感じられない.しかし,17世紀に入ると,印刷業者というよりはむしろ正音学者や教師の働きにより,標準的綴字が広範囲に展開することになった.1650年頃には事実上の標準化が達せられていたが,より意識的な「理性化」の段階に進んだのは理性の時代たる18世紀のことである.そして,Johnson の Dictionary (1755) が,これにだめ押しを加えた.それぞれ詳しくは,本記事末尾に付したリンク先や cat:spelling standardisation を参照されたい.

この緩慢とした綴字標準化の潮流を理解すべく,安井・久保田 (73) は幅広く先行研究に目を配った.16世紀以降のつづり字改革,印刷の普及,つづり字指南書の出版の歴史などを概観しながら,「?世紀半ば」というチェックポイントを設けつつ,以下のように分かりやすく要約している.

つづり字安定への地盤はすでに16世紀半ばころから見えはじめ,17世紀半ばごろには,確たる標準はなくとも,何か中心的な,つづり字統一への核ともいうべきものが生じはじめており,これが17世紀の末ごろまでにはしだいに純化され固定されて単一化の傾向をたどり,すでに Johnson's Dictionary におけるのとあまり違わないつづり字習慣が行われていたといえるだろう.

この問題を真に理解したと言うためには,チェックポイントとなる各時代の文献に読み慣れ,共時的感覚として標準化の程度を把握できるようでなければならないのだろう.

・ 「#193. 15世紀 Chancery Standard の through の異綴りは14通り」 ([2009-11-06-1])

・ 「#297. 印刷術の導入は英語の標準化を推進したか否か」 ([2010-02-18-1])

・ 「#871. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由」 ([2011-09-15-1])

・ 「#1312. 印刷術の発明がすぐには綴字の固定化に結びつかなかった理由 (2)」 ([2012-11-29-1])

・ 「#1384. 綴字の標準化に貢献したのは17世紀の理論言語学者と教師」 ([2013-02-09-1])

・ 「#1385. Caxton が綴字標準化に貢献しなかったと考えられる根拠」 ([2013-02-10-1])

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-08-26 Wed

■ #2312. 音素的表記を目指す綴字改革は正しいか? [spelling_reform][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][grapheme][grammatology][alphabet][writing][medium]

Roman alphabet という表音文字を用いる英語にあって,連綿と続いてきた綴字改革の歴史は,時間とともに乖離してきた綴字と発音の関係を,より緊密な関係へと回復しようとする試みだったと言い換えることができる.標題のように,より厳密な音素的表記への接近,と表現してもよい.

綴字改革は英語で "spelling_reform" と呼ばれるが,reform とは定義によれば "change that is made to a social system, an organization, etc. in order to improve or correct it" (OALD8) であるから「誤ったものを正す」という含意が強い.つまり,綴字改革を話題にする時点で,すでに既存の綴字体系が「誤っている」ことが,少なくとも何ほどか含意されていることになる.では,いかなる点で誤っているのか.ほとんど常に槍玉にあげられるのは,綴字に表音性が確保されていないという点だろう.実際のところ,現代英語の綴字は,以下の記事でも見てきたとおり,表語的(表形態素的)な性格が強いと議論することができるのであり,相対的に表音的な性格は弱い.

・ 「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1])

・ 「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1])

・ 「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1])

・ 「#2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1)」 ([2014-12-15-1])

・ 「#2059. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (2)」 ([2014-12-16-1])

・ 「#2097. 表語文字,同音異綴,綴字発音」 ([2015-01-23-1])

しかし,表音素的表記がより正しいという前提は,そもそも妥当なのだろうか.(漢字がその典型とされる)表形態素的表記は,それほど悪なのだろうか.この点について,安井・久保田 (92) の指摘は的確である.

つづり字改良という仕事は,要するに,「もっと音素的表記への改良」ということに,ほかならない.が,最も純粋に音素的である書記法が,あらゆる点で最良のものであるかというと,この場合も,それが一概によいともいえないのである.特に,書記言語を音声言語と対等な一次的言語の一つと考える立場からすれば,書記言語は言語音声をよく表していなければならなないということさえいえなくなってくる〔中略〕.英語にせよ,日本語にせよ,音素的表記でさえあれば,ただちに最良の表記法であるという考えは修正されるべきである.

引用で触れられているように,書記言語の独立性というより一般的な問題も,合わせて考慮されるべきだろう.writing という medium の独立性については,「#1665. 話しことばと書きことば (4)」 ([2013-11-17-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]) などの記事を参照されたい.

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

2015-08-21 Fri

■ #2307. 綴字の余剰性 (2) [spelling][redundancy][statistics][information_theory][alphabet][final_e][silent_letter]

「#2249. 綴字の余剰性」 ([2015-06-24-1]) で取り上げた話題.別の観点から英語綴字の余剰性を考えてみよう.

Roman alphabet のような単音文字体系にあっては,1文字と1音素が対応するのが原理的に望ましい.しかし,言語的,歴史的,その他の事情で,この理想はまず実現されないといってよい.現実は理想の1対1から逸脱しているのだが,では,具体的にはどの程度逸脱しているのだろうか.

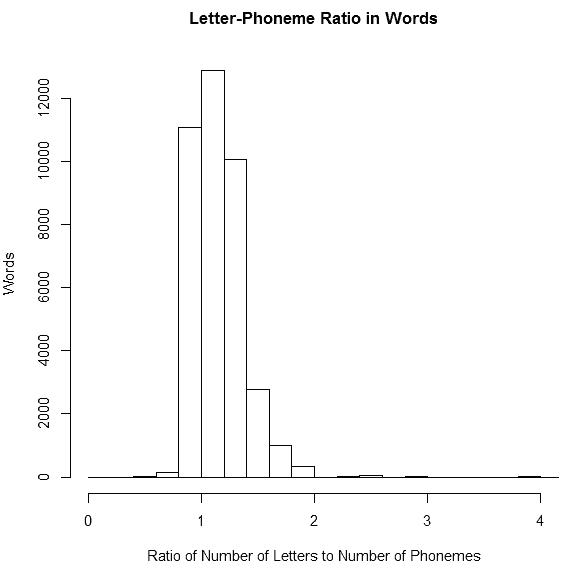

ここで,「#1159. MRC Psycholinguistic Database Search」 ([2012-06-29-1]) を利用して,文字と音素の対応の度合いをおよそ計測してみることができる.もし理想通りの単音文字体系であれば,単語の綴字を構成する文字数と,その発音を構成する音素数は一致するだろう.英語語彙を構成する各単語について,文字数と音素数の比を求め,その全体の平均値などの統計値を出せば,具体的な指標が得られるはずだ.綴字が余剰的 (redundancy) であるということはこれまでの議論からも予想されるところではあるが,具体的に,文字数対音素数の比は,2:1 程度なのか 3:1 程度なのか,どうなのだろうか.

まずは,MRC Psycholinguistic Database Search を以下のように検索して,単語ごとの,文字数,音素数,両者の比(=余剰性の指標)の一覧を得る(SQL文の where 以下は,雑音を排除するための条件指定).

select WORD, NLET, NPHON, NLET/NPHON as REDUNDANCY, PHON from mrc2 where NPHON != "00" and WORD != "" and PHON != "";

この一覧をもとに,各種の統計値を計算すればよい.文字数と音素数の比の平均値は,1.192025 だった.比を0.2刻みにとった度数分布図を示そう.

文字数別に比の平均値をとってみると,興味深いことに3文字以下の単語では余剰性は 1.166174 にとどまり,全体の平均値より小さくなる.一方,4文字から7文字までの単語では平均より高い 1.231737 という値を示す.8文字以上になると再び余剰性は小さくなり,1.157689 となる.文字数で数えて中間程度の長さの単語で余剰性が高く,短い単語と長い単語ではむしろ相対的に余剰性が低いようだ.この理由については詳しく分析していないが,「#1160. MRC Psychological Database より各種統計を視覚化」 ([2012-06-30-1]) でみたように,英単語で最も多い構成が8文字,6音素であるということや,final_e をはじめとする黙字 (silent_letter) の分布と何らかの関係があるかもしれない.

さて,全体の平均値 1.192025 で示される余剰性の程度がどれくらいのものなのか,ほかに比較対象がないので評価にしにくいが,主観的にいえば理想の値 1.0 から案外と隔たっていないなという印象である.英単語における文字と音素の関係は,「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1]) の比喩でいえば,そこそこよく張られた短めのロープで結ばれた関係ともいえるのではないか.

ただし,今回の数値について注意すべきは,英単語における文字と音素の対応を一つひとつ照らし合わせてはじき出したものではなく,本来はもっと複雑に対応するはずの両者の関係を,それぞれの長さという数値に落とし込んで比を取ったものにすぎないということだ.最終的に求めたい綴字の余剰性そのものではなく,それをある観点から示唆する指標といったほうがよいだろう.それでも,目安となるには違いない.

2015-08-06 Thu

■ #2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][medium][writing][spelling_reform][spelling_pronunciation]

英語の綴字と発音の関係,ひいては言語における書き言葉と話し言葉の関係について長らく考察しているうちに,頭のなかで標題のイメージが固まったきた.

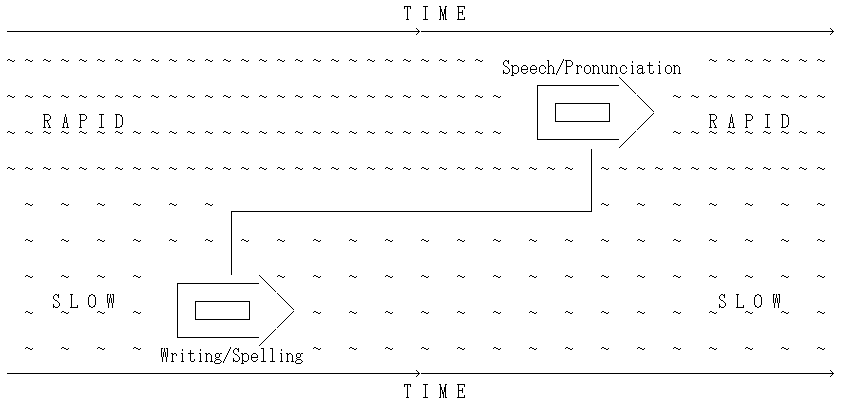

まず,大前提として発音(話し言葉)と綴字(書き言葉)が,原則としてそれぞれ独立した媒体であり,体系であるということだ.これについては,「#1928. Smith による言語レベルの階層モデルと動的モデル」 ([2014-08-07-1]) における Transmission や,「#1665. 話しことばと書きことば (4)」 ([2013-11-17-1]) も参照されたい.それぞれの媒体を,時間という川を流れる独立したボートに喩えよう.

さて,発音と綴字は確かに原則として独立してはいるが,一方で互いに依存し合う部分も少なくないのは事実である.この緩い関係を,2艘のボートをつなぐロープで表現する.かなりの程度に伸縮自在な,ゴムでできたロープに喩えるのがよいのではないかと思っている.

両媒体が互いに依存し合うとはいえ,圧倒的に多いのは,発音が綴字を先導するという関係である.発音は放っておいても,時間とともに変化していくのが常である.発音のボートは,常に早瀬側にあるものと理解することができる.一方,綴字は流れの緩やかな淵にあって,止まったり揺れ動いたりする程度の,比較的おとなしいボートである.したがって,時間が経てば経つほど,両ボートの距離は開いていく可能性が高い.しかし,2艘はロープでつながっている以上,完全に離れきってしまうわけではない.つかず離れずという距離感で,同じ川を流れていく.

稀な機会に,綴字のボートが発音のボートと横並びになる,あるいは追い越すことすらあるかもしれない.そのような事態は自然の川ではほとんどありえないが,言葉の世界では,人間が意図的にロープを短くしてやったり,綴字のボートを曳航してやるなどすれば可能である.これは,綴字改革 (spelling_reform) や綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) のようなケースに相当する.

この "Two-Boat Model" は,表音文字体系をもつ言語においてはおそらく一般的に当てはまるだろう.話し言葉と書き言葉の媒体は,半ば独立しながらも半ば依存し合っており,互いに干渉しすぎることなく,つかず離れずで共存しているのである.

2015-08-04 Tue

■ #2290. 形容詞屈折と長母音の短化 [final_e][ilame][inflection][vowel][phonetics][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][adjective][afrikaans][syntagma_marking]

<look>, <blood>, <dead>, <heaven>, などの母音部分は,2つの母音字で綴られるが,発音としてはそれぞれ短母音である.これは,近代英語以前には予想される通り2拍だったものが,その後,短化して1拍となったからである.<oo> の綴字と発音の関係,およびその背景については,「#547. <oo> の綴字に対応する3種類の発音」 ([2010-10-26-1]),「#1353. 後舌高母音の長短」 ([2013-01-09-1]),「#1297. does, done の母音」 ([2012-11-14-1]),「#1866. put と but の母音」 ([2014-06-06-1]) で触れた.<ea> については,「#1345. read -- read -- read の活用」 ([2013-01-01-1]) で簡単に触れたにすぎないので,今回の話題として取り上げたい.

上述の通り,<ea> は本来長い母音を表わした.しかし,すでに中英語にかけての時期に3子音前位置で短化が起こっており,dream / dreamt, leap / leapt, read / read, speed / sped のような母音量の対立が生じた (cf. 「#1854. 無変化活用の動詞 set -- set -- set, etc.」 ([2014-05-25-1])) .また,単子音前位置においても,初期近代英語までにいくつかの単語において短化が生じていた (ex. breath, dead, dread, heaven, blood, good, cloth) .これらの異なる時代に生じた短化の過程については「#2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化」 ([2014-12-09-1]) や「#2063. 長母音に対する制限強化の歴史」 ([2014-12-20-1]) で見たとおりであり,純粋に音韻史的な観点から論じることもできるかもしれないが,特に初期近代英語における短化は一部の語彙に限られていたという事情があり,問題を含んでいる.

Görlach (71) は,この議論に,間接的ではあるが(統語)形態的な観点を持ち込んでいる.

Such short vowels reflecting ME long vowel quantities are most frequent where ME has /ɛː, oː/ before /d, t, θ, v, f/ in monosyllabic words, but even here they occur only in a minority of possible words. It is likely that the short vowel was introduced on the pattern of words in which the occurrence of a short or a long vowel was determined by the type of syllable the vowel appeared in (glad vs. glade). When these words became monosyllabic in all their forms, the conditioning factor was lost and the apparently free variation of short/long spread to cases like (dead). That such processes must have continued for some time is shown by words ending in -ood: early shortened forms (flood) are found side by side with later short forms (good) and those with the long vowel preserved (mood).

子音で終わる単音節語幹の形容詞は,後期中英語まで,統語形態的な条件に応じて,かろうじて屈折語尾 e を保つことがあった (cf. 「#532. Chaucer の形容詞の屈折」 ([2010-10-11-1])) .屈折語尾 e の有無は音節構造を変化させ,語幹母音の長短を決定した.1つの形容詞におけるこの長短の変異がモデルとなって,音節構造の類似したその他の環境においても長短の変異(そして後の短音形の定着)が見られるようになったのではないかという.ここで Görlach が glad vs. glade の例を挙げながら述べているのは,本来は(統語)形態的な機能を有していた屈折語尾の -e が,音韻的に消失していく過程で,その機能を失い,語幹母音の長短の違いにその痕跡を残すのみとなっていったという経緯である (cf. 「#295. black と Blake」 ([2010-02-16-1])) .関連して,「#977. 形容詞の屈折語尾の衰退と syntagma marking」 ([2011-12-30-1]) で触れたアフリカーンス語における形容詞屈折語尾の「非文法化」の事例が思い出される.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2015-08-02 Sun

■ #2288. ショッピングサイトでのスペリングミスは致命的となりうる [sociolinguistics][spelling]

社会言語学に,言語市場 (linguistic marketplace) という概念がある.社会において,言語は文字通りにカネの回る市場であるという考え方だ.言語と経済の関係が密接であることは,私たちもよく知っている.世界経済の「通貨」は英語を筆頭とするリンガ・フランカ (lingua_franca) であるし,多言語を使いこなせる人は市場価値が高いとも言われる.営業マンは言葉遣いが巧みであれば業績が上がるだろうし,通訳や翻訳などは直接に言語で稼ぐ業種である.ほかにも,セネガルにおいて,言葉による挨拶の仕方とその人の経済力が結びついていることは,「#1623. セネガルの多言語市場 --- マクロとミクロの社会言語学」 ([2013-10-06-1]) で見たとおりである.このように,言語,言語能力,言語使用には,市場価値がある.

言語の市場価値という観点から,興味深い指摘がある.ウェブ上のショッピングサイトでは,スペリングの正確さが売上に直結する重要な要素であるということだ.だましサイトには間違えたスペリングやいかがわしい表記が溢れていることはよく知られており,買い物客はサイトにおける綴字ミスには敏感なのである.買い物客は,売り手がいかに「きちんと」商売しているかを,部分的に綴字の正確さで測っているという.Horobin (4--5) が次のように述べている.

. . . there is an economic argument for the importance of correct spelling. Charles Duncombe, an entrepreneur with various online business interests, has suggested that spelling errors on a website can lead directly to a loss of custom, potentially causing online businesses huge losses in revenue (BBC News, 11 July 2011). This is because spelling mistakes are seen by consumers as a warning sign that a website might be fraudulent, leading shoppers to switch to a rival website in preference. Duncombe measured the revenue per visitor to one of his websites, discovering that it doubled once a spelling mistake had been corrected. . . . So the message is clear: good spelling is vital if you want to run a profitable online retail company, or be a successful email spammer.

言語と経済の関係については様々な論考があるが,「#2163. 言語イデオロギー」 ([2015-03-30-1]),「#2166. argot (隠語)の他律性」 ([2015-04-02-1]) で取り上げたものとして Irvine の論文を挙げておこう.

・ Irvine, Judith T. "When Talk Isn't Cheap: Language and Political Economy." American Ethnologist 16 (1989): 248--67.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2015-07-29 Wed

■ #2284. eye の発音の歴史 [pronunciation][oe][phonetics][vowel][spelling][gvs][palatalisation][diphthong][three-letter_rule]

eye について,その複数形の歴史的多様性を「#219. eyes を表す172通りの綴字」 ([2009-12-02-1]) で示した.この語は,発音に関しても歴史的に複雑な過程を経てきている.今回は,eye の音変化の歴史を略述しよう.

古英語の後期ウェストサクソン方言では,この語は <eage> と綴られた.発音としては,[æːɑɣe] のように,長2重母音に [g] の摩擦音化した音が続き,語尾に短母音が続く音形だった.まず,古英語期中に語頭の2重母音が滑化して [æːɣe] となった.さらにこの母音は上げの過程を経て,中英語期にかけて [eːɣe] という音形へと発達した.

一方,有声軟口蓋摩擦音は前に寄り,摩擦も弱まり,さらに語尾母音は曖昧化して /eːjə/ が出力された.語中の子音は半母音化し,最終的には高母音 [ɪ] となった.次いで,先行する母音 [e] はこの [ɪ] と融合して,さらなる上げを経て,[iː] となるに至る.語末の曖昧母音も消失し,結果として後期中英語には語全体として [iː] として発音されるようになった.

ここからは,後期中英語の I [iː] などの語とともに残りの歴史を歩む.高い長母音 [iː] は,大母音推移 (gvs) を経て2重母音化し,まず [əɪ] へ,次いで [aɪ] へと発達した.標準変種以外では,途中段階で発達が止まったり,異なった発達を遂げたものもあるだろうが,標準変種では以上の長い過程を経てきた.以下に発達の歴史をまとめて示そう.

| /æːɑɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /æːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːɣe/ |

| ↓ |

| /eːjə/ |

| ↓ |

| /eɪə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iːə/ |

| ↓ |

| /iː/ |

| ↓ |

| /əɪ/ |

| ↓ |

| /aɪ/ |

なお,現在の標準的な綴字 <eye> は古英語 <eage> の面影を伝えるが,共時的には「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]) を遵守しているかのような綴字となっている.場合によっては *<ey> あるいは *<y> のみでも用を足しうるが,ダミーの <e> を活用して3文字に届かせている.

2015-07-25 Sat

■ #2280. <x> の話 [alphabet][grapheme][x][pronunciation][spelling][verners_law]

英語アルファベットの24文字目の <x> には,日陰者のイメージがつきまとう.まず,1文字なのに2つの子音結合 /ks/ に対応するというのが怪しい.頻度の点からも,「#308. 現代英語の最頻英単語リスト」 ([2010-03-01-1]) で示した通り,<z>, <q>, <j> に次いで稀な文字である.無ければ無いで済ませられそうな文字だ.

英語史における <x> の役割を簡単に振り返ってみよう.この文字素は,確かに /ks/ あるいは /hs/ に対応する文字として古英語から見られた.しかし,eax (axe), fleax (flax), fox, oxa (ox), siex (six), wæx (wax) などの一握りの単語に現われるのみで,当初から目立った文字ではなかった (Upward and Davidson 62) .これらの単語は,現代英語へも <x> を保ったまま伝わっている.その後,中英語期に入ると,方言によっては <x> を多用するものもあったが (cf. 「#663. 中英語方言学における綴字と発音の関係」 ([2011-02-19-1])) ,やはり概して頻度の高い文字ではなかった.

しかし,初期近代英語期になると,<x> はラテン語やギリシア語からの借用語に多く含まれていたために,これまでの時代に比べて出現頻度が増した.接頭辞 ex- をもつ多数の語に加え,語中で anxious, approximate, auxiliary, axis, maximum, nexus, noxious, toxic などに現われたし,語末でも apex, appendix, crux, index などが入った.ほかにも complexion, crucifixion, connexion, inflexion などの -xion 語尾や,近代フランス語からの faux pas, grand prix,さらにフランス語の複数形を表わす bureaux, chateaux, jeux など,<x> の生じる機会が目に見えて増した.

<x> はとりわけ専門的な借用語語彙に多く現われる.語頭,語中,語末それぞれの環境に現われる <x> の例をもう少し見てみよう (Upward and Davidson 213--14) .

[語頭]: xenophobia, Xerox, xylophone

[語中]: anorexia, apoplexy, asphyxia, axiom, axis, dyslexia, galaxy, lexical, hexagon, oxygen, paroxysm, taxonomy

[語末]: anthrax, calx, calyx, climax, coccyx, helix, larynx, onyx, paradox, phalanx, pharynx, phlox, phoenix, sphinx, syntax, thorax

このようにラテン語やギリシア語を中心とした借用語彙の貢献が大きいが,そのほかにも古英語から続く前述の語群が <x> を保持したばかりでなく,cox (< cockswain) や smallpox (< pl. of small pock) などの短縮によって作られた語に <x> が見られるようになったことが注目される.20世紀には,同様の短縮の過程を経て sox (< socks), fax (< facsimile), proxy (< proc'cy < procuracy) が生まれている.

The X of cox 'boatman' arose from cockswain, while pox (as in smallpox) was respelt from the plural of pock (as in pockmarked). These replacements of CC or CKS by X are first attested in EModE; other examples are 20th-century: sox for socks, fax from facsimile. Proxy < proc'cy < procuracy. (Upward and Davidson 168)

さて,現代英語における <x> の発音への対応を,Carney (377--78) に拠って見てみよう.語頭では,上記の第1群の語にみられる通り /z/ が基本である.ただし,例外として Xhosa /ˈkoʊsə/ や Xmas /ˈkrɪsməs, ˈɛksməs/ には注意 (<Xmas> は Christ の語頭子音に対応するギリシア語文字 <Χ> に由来).語頭以外では,続く母音に強勢があれば /gz/ がルールだ (ex. exact, exaggerate, exalt, examine, executive, exempt, exert, exhibit, exhort, exist, exonerate, exotic, exult) .それ以外は,/ks/ が基本である (ex. axe, boxing, extra, fox, mixture, orthodox, praxis, texture, vixen, wax) . 派生語間での /ks/ と /gs/ の交替については,「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) と「#2230. 英語の摩擦音の有声・無声と文字の問題」 ([2015-06-05-1]) を参照されたい.ほかには,<i> や <u> の前位置で,/kʃ/ となることがある (ex. anxious, connexion, flexure, luxury) .

<z> が歴史的に日陰者だったことは「#446. しぶとく生き残ってきた <z>」 ([2010-07-17-1]) でも確認したとおりだが,<x> も負けていない.未知の人物や数を表わすのに x をもってする慣習があるが,この由来は不詳である.もしかすると,原因なのか結果なのか,ここには <x> の日陰者としての歩みが関与しているのではないかとも疑われる・・・.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2015-07-19 Sun

■ #2274. heart の綴字と発音 [spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][pronunciation][vowel]

強勢音節における <ear> の綴字で表わされる発音には,3種類がある.hear や beard のような /ɪər/,learn や dearth のような /ər/,heart や hearth のような /ɑr/ である.とりわけ子音が後続する場合には,2つめの learn のように /ər/ の発音となるのが普通で,beard や heart のタイプは珍しい.ここでは特に heart や hearth の不規則性について考えたい.

この問題を考察するにあたっては,中英語期の音変化について知る必要がある.中英語の /er/ に対応する綴字には,典型的なものとして <er> と <ear> があった.後者の母音は2文字で綴られることからわかるとおり元来は二重母音あるいは長母音を表わしたが,後ろに子音が続く環境では往々にして短化したために,<er> と等価になった.14世紀末,おそらく Chaucer の時代あたりに,非常に多くの単語において,この <er> あるいは <ear> で表わされた /er/ の母音が下げの過程を経て,/ar/ へと変化した.この音変化に伴って,綴字も <ar> と書き換えられる例が多かった.例えば,dark (< derk), darling (< derling), far (< fer), star (< ster), starve (< sterve), yard (< yerde) である.しかし,変化前後の両音がしばらく揺れを示していたことを反映し,綴字でも <ar> へ変更されず,<er> や <ear> を保ったものもあった.17世紀頃には発音は /ar/ が普通となっていたが,18世紀には綴字発音の影響で /er/ に戻ったものもあり,関与する単語群において,この発音と綴字の関係は安定感を欠くことになった.結果として,発音は /ar/ へ変化したものが標準化したけれど,綴字は <er> や <ear> で据え置かれるという例が生じてしまった.

<er> の例には,sergeant やイギリス発音としての clerk, Derby などがある(cf. 「#211. spelling pronunciation」 ([2009-11-24-1]), 「#1343. 英語の英米差を整理(主として発音と語彙)」 ([2012-12-30-1])) .また,<ear> の例としては heart, hearth のほか,hearken (おそらく hear の綴字に影響を受けたもの.<harken> の綴字もあり)や固有名詞 Liskeard などがある.Kearney などでは,発音としては /ər/ と /ɑr/ の両方の可能性がある(以上,Carney (311),Jespersen (197--99), 中尾 (207--08), Scragg (49) などを参照した).

beard の示す不規則性については,現在同じ母音をもつ fierce, Pierce にもかつて /ər/ という変異発音が存在したことを述べておこう.逆に,現在は /ər/ をもつ vers に /ɪər/ の変異発音が聞かれたこともあった (Jespersen 365) .

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2015-06-25 Thu

■ #2250. English の語頭母音(字) [pronunciation][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][i-mutation][haplology]

現代英語で強勢音節における <en> という綴字の最初の母音が /ˈɪŋ/ に対応するのは,English と England という単語においてのみである.あまりに見慣れているので違和感を覚えることすらないが,この2語はきわめて不規則な綴字と発音の関係を示している.歴史的背景を追ってみよう.

「#1145. English と England の名称」 ([2012-06-15-1]) で説明したように,English と England は,それぞれ古英語における派生語,複合語である.前者は基体の Engle (or Angle)(アングル人)に形容詞を作る接尾辞 -isc を付した形態であり,後者は同じ基体の複数属格形に land を付した Englaland から la の haplography (重字脱落)を経た形態である.古英語の基体 Engle は,ゲルマン祖語 *anȝli- に遡り,釣針 (angle) の形をした Schleswig の一地方名と関連づけられるが,これがラテン語に借用されて Anglus (nom. sg.) や Angli (nom. pl.) として用いられたものが,古英語へ入ったものである.

ゲルマン祖語の語頭に示される [ɑ] の母音は,次の音節の i による i-mutation を経て前寄りの [æ] となったが,鼻音の前ではさらに上げを経て [ɛ] に至った.この2つめの上げは,第2の i-mutation ともいうべきもので,Campbell (75) によると後期古英語のテキストにはよく反映されている(ただし,中英語の South-East Midland に相当する地域では生じなかった).同変化を経た語としては,menn (< *manni), ende (< *andja) などがある(中尾,p. 222--24).一方,この一連の音変化を反映せずに現代において定着した語としては,(East) Anglia や Anglo-Saxon などがある.

さて,14世紀になると /eŋ/ > /iŋ/ の変化が例証されるようになる.senge > singe, henge > hinge, streng > string, weng > wing, þenken > þinken, enke > inke などである(中尾,p. 169).音としては,ゲルマン祖語のもともとの低母音 [ɑ] が,上げの過程を何度も経てついに高母音 [ɪ] になってしまったわけである.

さて,上に挙げた単語群では,この母音の上げに伴い,後の標準的な綴字でも <eng> から <ing> と書き改められて現代に至るが,English, England については,一時期は行なわれていた <Inglish>, <Ingland> などの綴字が標準化することはなく,<Eng>- が存続することになった (cf. 「#1436. English と England の名称 (2)」 ([2013-04-02-1])) .その理由はよくわからないが,いずれにせよ,この2語については不規則な綴字と発音の関係が定着してしまったという顛末だ.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2015-06-24 Wed

■ #2249. 綴字の余剰性 [spelling][orthography][cgi][web_service][redundancy][information_theory][punctuation][shortening][alphabet][q]

言語の余剰性 (redundancy) や費用の問題について,「#1089. 情報理論と言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-20-1]),「#1090. 言語の余剰性」 ([2012-04-21-1]),「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1098. 情報理論が言語学に与えてくれる示唆を2点」 ([2012-04-29-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) などで議論してきた.言語体系を全体としてみた場合の余剰性のほかに,例えば英語の綴字という局所的な体系における余剰性を考えることもできる.「#1599. Qantas の発音」 ([2013-09-12-1]) で少しく論じた通り,例えば <q> の後には <u> が現われることが非常に高い確立で期待されるため,<qu> は余剰性の極めて高い文字連鎖ということができる.

英語の綴字体系は全体としてみても余剰性が高い.そのため,英語の語彙,形態,統語,語用などに関する理論上,運用上の知識が豊富であれば,必ずしも正書法通りに綴られていなくとも,十分に文章を読解することができる.個々の単語の綴字の規範からの逸脱はもとより,大文字・小文字の区別をなくしたり,分かち書きその他の句読法を省略しても,可読性は多少落ちるものの,およそ解読することは可能だろう.一般に言語の変化や変異において形式上の短縮 (shortening) が日常茶飯事であることを考えれば,非標準的な書き言葉においても,綴字における短縮が頻繁に生じるだろうことは容易に想像される.情報理論の観点からは,可読性の確保と費用の最小化は常に対立しあう関係にあり,両者の力がいずれかに偏りすぎないような形で,綴字体系もバランスを維持しているものと考えられる.

いずれか一方に力が偏りすぎると体系として機能しなくなるものの,多少の偏りにとどまる限りは,なんとか用を足すものである.主として携帯機器用に提供されている最近の Short Messages Service (SMS) では,使用者は,字数の制約をクリアするために,メッセージを解読可能な範囲内でなるべく圧縮する必要に迫られる.英語のメッセージについていえば,綴字の余剰性を最小にするような文字列処理プログラムにかけることによって,実際に相当の圧縮率を得ることができる.電信文体の現代版といったところか.

実際に,それを体験してみよう.以下の "Text Squeezer" は,母音削除を主たる方針とするメッセージ圧縮プログラムの1つである(Perl モジュール Lingua::EN::Squeeze を使用).入力するテキストにもよるが,10%以上の圧縮率を得られる.出力テキストは,確かに可読性は落ちるが,慣れてくるとそれなりの用を足すことがわかる.適当な量の正書法で書かれた英文を放り込んで,英語正書法がいかに余剰であるかを確かめてもらいたい.

2015-06-10 Wed

■ #2235. 3文字規則 [spelling][orthography][final_e][personal_pronoun][three-letter_rule]

現代英語の正書法には,「3文字規則」と呼ばれるルールがある.超高頻度の機能語を除き,単語は3文字以上で綴らなければならないというものだ.英語では "the three letter rule" あるいは "the short word rule" といわれる.Jespersen (149) の記述から始めよう.

4.96. Another orthographic rule was the tendency to avoid too short words. Words of one or two letters were not allowed, except a few constantly recurring (chiefly grammatical) words: a . I . am . an . on . at . it . us . is . or . up . if . of . be . he . me . we . ye . do . go . lo . no . so . to . (wo or woe) . by . my.

To all other words that would regularly have been written with two letters, a third was added, either a consonant, as in ebb, add, egg, Ann, inn, err---the only instances of final bb, dd, gg, nn and rr in the language, if we except the echoisms burr, purr, and whirr---or else an e . . .: see . doe . foe . roe . toe . die . lie . tie . vie . rye, (bye, eye) . cue, due, rue, sue.

4.97 In some cases double-writing is used to differentiate words: too to (originally the same word) . bee be . butt but . nett net . buss 'kiss' bus 'omnibus' . inn in.

In the 17th c. a distinction was sometimes made (Milton) between emphatic hee, mee, wee, and unemphatic he, me, we.

2文字となりうるのは機能語がほとんどであるため,この規則を動機づけている要因として,内容語と機能語という語彙の下位区分が関与していることは間違いなさそうだ.

しかし,上の引用の最後で Milton が hee と he を区別していたという事実は,もう1つの動機づけの可能性を示唆する.すなわち,機能語のみが2文字で綴られうるというのは,機能語がたいてい強勢を受けず,発音としても短いということの綴字上の反映ではないかと.これと関連して,off と of が,起源としては同じ語の強形と弱形に由来することも思い出される (cf. 「#55. through の語源」 ([2009-06-22-1]),「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]),「#1775. rob A of B」 ([2014-03-07-1])) .Milton と John Donne から,人称代名詞の強形と弱形が綴字に反映されている例を見てみよう (Carney 132 より引用).

so besides

Mine own that bide upon me, all from mee

Shall with a fierce reflux on mee redound,

On mee as on thir natural center light . . .

Did I request thee, Maker, from my Clay

To mould me Man, did I sollicite thee

From darkness to promote me, or here place

In this delicious Garden?

(Milton Paradise Lost X, 737ff.)

For every man alone thinkes he hath got

To be a Phoenix, and that then can bee

None of that kinde, of which he is, but hee.

(Donne An Anatomie of the World: 216ff.)

Carney (133) は,3文字規則の際だった例外として <ox> を挙げ (cf. <ax> or <axe>),完全無欠の規則ではないことは認めながらも,同規則を次のように公式化している.

Lexical monosyllables are usually spelt with a minimum of three letters by exploiting <e>-marking or vowel digraphs or <C>-doubling where appropriate.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2015-06-09 Tue

■ #2234. <you> の綴字 [personal_pronoun][spelling][orthography][pronunciation]

「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]) では,きわめて例外的な綴字としての <you> について触れた.原則として <u> で終わる語はないのだが,この最重要語は特別のようである.だが,非常に関連の深いもう1つの語も,同じ例外を示す.古い2人称単数代名詞 <thou> である.俄然この問題がおもしろくなってきた.関係する記述を探してみると,Upward and Davidson (188) が,これについて簡単に触れている.

OU and OW have become fixed in spellings mainly according to their position in the word, with OU in initial or medial positions before consonants . . . .

・ OU is nevertheless found word-finally in you and thou, and in some borrowings from or via Fr: chou, bayou, bijou, caribou, etc.

・ The pronunciation of thou arises from a stressed form of the word; hence OE /uː/ has developed to /aʊ/ in the GVS. The pronunciation of you, on the other hand, derives from an unstressed form /jʊ/, from which a stressed form /juː/ later developed.

Upward and Davidson にはこれ以上の記述は特になかったので,さらに詳しく調査する必要がある.共時的にみれば,*<yow> と綴る方法もあるかもしれないが,これは綴字規則に照らすと /jaʊ/ に対応してしまい都合が悪い.<ewe> や <yew> の綴字は,すでに「雌山羊」「イチイ」を意味する語として使われている.ほかに,*<yue> のような綴字はどうなのだろうか,などといろいろ考えてみる.所有格の <your> は語中の <ou> として綴字規則的に許容されるが,綴字規則に則っているのであれば,対応する発音は */jaʊə/ となるはずであり,ここでも問題が生じる.謎は深まるばかりだ.

上の引用でも触れられている you の発音について,より詳しくは「#2077. you の発音の歴史」([2015-01-03-1]) を参照.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-06-05 Fri

■ #2230. 英語の摩擦音の有声・無声と文字の問題 [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][consonant][phoneme][grapheme][degemination][x][phonemicisation]

5月16日付の「素朴な疑問」に,<s> と <x> の綴字がときに無声子音 /s, ks/ で,ときに有声子音 /z, gz/ で発音される件について質問が寄せられた.語頭の <s> は必ず /s/ に対応する,強勢のある母音に先行されない <x> は /gz/ に対応する傾向があるなど,実用的に参考となる規則もあるにはあるが,最終的には単語ごとに決まっているケースも多く,絶対的なルールは設けられないのが現状である.このような問題には,歴史的に迫るよりほかない.

英語史的には,/(k)s, (g)z/ にとどまらず,摩擦音系列がいかに綴られてきたかを比較検討する必要がある.というのは,伝統的に,古英語では摩擦音の声の対立はなかったと考えられているからである.古英語には摩擦音系列として /s/, /θ/, /f/ ほかの音素があったが,対応する有声摩擦音 [z], [ð], [v] は有声音に挟まれた環境における異音として現われたにすぎず,音素として独立していなかった (cf. 「#1365. 古英語における自鳴音にはさまれた無声摩擦音の有声化」 ([2013-01-21-1]),「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1])).文字は音素単位で対応するのが通常であるから,相補分布をなす摩擦音の有声・無声の各ペアに対して1つの文字素が対応していれば十分であり,<s>, <þ> (or <ð>), <f> がある以上,<z> や <v> などの文字は不要だった.

しかし,これらの有声摩擦音は,中英語にかけて音素化 (phonemicisation) した.その原因については諸説が提案されているが,主要なものを挙げると,声という弁別素性のより一般的な応用,脱重子音化 (degemination),南部方言における語頭摩擦音の有声化 (cf. 「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]),「#2226. 中英語の南部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こった理由」 ([2015-06-01-1])),有声摩擦音をもつフランス語彙の借用などである(この問題に関する最新の論文として,Hickey を参照されたい).以下ではとりわけフランス語彙の借用という要因を念頭において議論を進める.

有声摩擦音が音素の地位を獲得すると,対応する独立した文字素があれば都合がよい./v/ については,それを持ち込んだ一員とも考えられるフランス語が <v> の文字をもっていたために,英語へ <v> を導入することもたやすかった.しかも,フランス語では /f/ = <f>, /v/ = <v> (実際には <<v>> と並んで <<u>> も用いられたが)の関係が安定していたため,同じ安定感が英語にも移植され,早い段階で定着し,現在に至る.現代英語で /f/ = <f>, /v/ = <v> の例外がきわめて少ない理由である (cf. of) .

/z/ については事情が異なっていた.古英語でも古フランス語でも <z> の文字はあったが,/s, z/ のいずれの音に対しても <s> が用いられるのが普通だった.フランス語ですら /s/ = <s>, /z/ = <z> の安定した関係は築かれていなかったのであり,中英語で /z/ が音素化した後でも,/z/ = <z> の関係を作りあげる動機づけは /v/ = <v> の場合よりも弱かったと思われる.結果として,<s> で有声音と無声音のいずれをも表わすという古英語からの習慣は中英語期にも改められず,その「不備」が現在にまで続いている.

/ð/ については,さらに事情が異なる.古英語より <þ> と <ð> は交換可能で,いずれも音素 /θ/ の異音 [θ] と [ð] を表わすことができたが,中英語期に入り,有声音と無声音がそれぞれ独立した音素になってからも,それぞれに独立した文字素を与えようという機運は生じなかった.その理由の一部は,消極的ではあるが,フランス語にいずれの音も存在しなかったことがあるだろう.

/v/, /z/, /θ/ が独立した文字素を与えられたかどうかという点で異なる振る舞いを示したのは,フランス語に対応する音素と文字素の関係があったかどうかよるところが大きいと論じてきたが,ほかには各々の音素化が互いに異なるタイミングで,異なる要因により引き起こされたらしいことも関与しているだろう.音素化の早さと,新音素と新文字素との関係の安定性とは連動しているようにも見える.現代英語における摩擦音系列の発音と綴字の関係を論じるにあたっては,歴史的に考察することが肝要だろう.

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Middle English Voiced Fricatives and the Argument from Borrowing." Approaches to Middle English: Variation, Contact and Change. Ed. Juan Camilo Conde-Silvestre and Javier Calle-Martín. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 2015. 83--96.

2015-06-02 Tue

■ #2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか [spelling][final_e][orthography][silent_letter][grapheme][sobokunagimon]

現代英語には,原則として <u> の文字で終わる単語がない.実際には借用語など周辺的な単語ではありうるが,通常用いられる語彙にはみられない.これはなぜだろうか.

重要な背景の1つとして,英語史において長らく <u> と <v> が同一の文字として扱われてきた事実がある.この2つの文字は中英語以降用いられてきたし,単語内での位置によって使い分けがあったことは事実である.しかし,「#373. <u> と <v> の分化 (1)」 ([2010-05-05-1]),「#374. <u> と <v> の分化 (2)」 ([2010-05-06-1]) でみてきたように,分化した異なる文字としてとらえられるようになったのは近代英語期であり,辞書などでは19世紀に入ってまでも同じ文字素として扱われていたほどだった.<u> と <v> は,長い間ともに母音も子音も表わし得たのである.

この状況においては,例えば中英語で <lou> という綴字をみたときに,現代の low に相当するのか,あるいは love のことなのか曖昧となる.このような問題に対して,中英語での解決法は2種類あったと思われる.1つは,「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1]) で触れたように,<u> 単独ではなく <ue> と綴ることによって /v/ を明示的に表わすという方法である.<e> を発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) 的に用いるという処方箋だ.これにより,love は <loue> と綴られることになり,low と区別しやすくなる.この -<ue> の綴字習慣は,後に最初の文字が <v> に置き換えられ,-<ve> として現在に至る.

上の方法が明示的に子音 /v/ を表わそうとする努力だとすれば,もう1つの方法は明示的に母音 /u/ を表わそうとする努力である.それは,特に語末において母音字としての <u> を避け,曖昧性を排除する <w> を採用することだったのではないか.かくして <ou> に限らず <au>, <eu> などの二重母音字は語末において <ow>, <aw>, <ew> と綴られるようになった.<u> と <v> が分化していたならば,上の問題は生じず,素直に <lov> "love" と <lou> "low" という対になっていたかもしれないが,分化してなかったために,それぞれについて独自の解決法が模索され,結果として <loue> と <low> という綴字対が生じることになったのだろう.このようにして,語末に <u> の生じる機会が減ることになった.

今ひとつ考えられるのは,語末における <i> の一般的な不使用との平行性だ.通常,語末には <i> は生じず,代わりに <y> や <ie> が用いられる.これは,語末に <u> が生じず,代わりに <w> や <ue> が用いられるのと比較される.<i> と <u> の文字に共通するのは,中世の書体ではいずれも縦棒 (minim) で構成されることだ.先行する文字にも縦棒が含まれる場合には,縦棒が連続して現われることになり判別しにくい.そこで,<y> や <w> とすれば判別しやすくなるし,語末では装飾的ともなり,都合がよい(cf. 「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]),「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]),「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1])).また,別の母音に続けて用いると,<ay>, <ey>, <oy>, <aw>, <ew>, <ow> などのように2重母音字であることを一貫して標示することもでき,メリットがある.

以上のような状況が相まって,結果として <u> が語末に現われにくくなったものと推測される.ただし,重要な例外が1つあるので,大名 (45) から取り上げておきたい.

外来語などは別として,英語本来の語は基本的に u で終わることはありません.語末では代わりに w を使うか (au, ou, eu → aw, ow,ew), blue, sue のように,e を付けて,u で終わらないようにします.you は英語を勉強し始めてすぐに学ぶ単語ですが,実は u で終わる珍しい綴りの単語ということになります.

・ 大名 力 『英語の文字・綴り・発音のしくみ』 研究社,2014年.

2015-05-11 Mon

■ #2205. proceed vs recede [spelling][latin][french][spelling_pronunciation_gap][orthography]

標題の語は,語源的には共通の語幹をもち,接頭辞が異なるだけなのだが,現代英語ではそれぞれ <proceed>, <recede> と異なる綴字を用いる.これは一体なぜなのかと,学生からの鋭い質問が寄せられた.

なるほど語幹はラテン語 -cedere (go, proceed) あるいはそのフランス語形 -céder に由来するので,語源的には <cede> の綴字がふさわしいところだろうが,語によって <ceed> か <cede> かが決まっている.Upward and Davidson (103) は,次の10語を挙げている.

・ -<ceed>: exceed, proceed, succeed

・ -<cede>: cede, accede, concede, intercede, precede, recede, secede

いずれの語も,中英語期や初期近代英語に最初に現われたときの綴字は -<cede> だったのだが,混乱期を経て,上の状況に収まったという.初期近代英語では interceed, preceed, recead/receed なども行われていたが,標準的にはならなかった.振り返ってみると -<cede> が優勢だったように見えるが,類推と逆類推の繰り返しにより,各々がほとんどランダムに決まったといってよいのではないか.綴字と発音の一対多の関係をよく表わす例だろう.

このような混乱に乗じて,同一単語が2語に分かれた例がある.discrete と discreet だ.いずれもラテン語 discretus に遡るが,綴字の混乱を逆手に取るかのようにして,2つの異なる語へ分裂した.しかし,だからといって何かが分かりやすくなったわけでもないが・・・.

近代英語では <e>, <ee>, <ea> の三つ巴の混乱も珍しくなく,complete, compleat, compleet などと目まぐるしく代わった.この混乱の落とし子ともいうべきものが,speak vs speech のような対立に残存している (Upward and Davidson 104; cf. 「#49. /k/ の口蓋化で生じたペア」 ([2009-06-16-1])) .関連して,「#436. <ea> の綴りの起源」 ([2010-07-07-1]) も要参照.

-<cede> vs -<ceed> の例に限らず,長母音 /iː/ に対応する綴字の選択肢の多さは目を見張る.いくつか挙げてみよう.

・ <ae>: Caeser, mediaeval

・ <ay>: quay

・ <e>: be, he, mete

・ <ea>: lead, meat, sea

・ <ee>: feet, meet, see

・ <ei>: either, receive, seize,

・ <eigh>: Leigh

・ <eip>: receipt

・ <eo>: feoff, people

・ <ey>: key

・ <i>: chic, machine, Philippines

・ <ie>: believe, chief, piece

・ <oe>: amoeba, Oedipus

探せば,ほかにもあると思われる.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-02-24 Tue

■ #2129. ドイツ語史における final e の問題 [final_e][ilame][orthography][spelling][prescriptive_grammar][german][hypercorrection]

英語史における final_e の問題は,発音においても綴字においても重要な問題である.後期古英語から初期中英語にかけて著しく進行した屈折語尾の水平化 (levelling of inflection) の諸症状のうち,final e の消失は後の英語の歴史に最も広範な影響を及ぼしたといってよいだろう.これにより,古英語からの名詞,形容詞,動詞などの屈折体系は大打撃を受け,英語は統語論を巻き込む形で形態論を再編成することとなった.特に形容詞の -e 語尾の問題については,ilame の各記事で扱ってきた.

後期中英語までには,概ね final e は音声的に無音となっていたと考えられるが,綴字上は保持されたり復活したりすることも多く,規範的な機能を獲得しつつあった.Chaucer の諸写本では,格式が高いものほど final e がよく保たれているなどの事実が確認されており,当時 final e のもつ保守性と規範性が意識されていたことがうかがえる.初期中英語までは屈折語尾として言語的機能を有していた final e が,後期中英語以降になるに及んで社会言語学的・文体的機能を担うようになってきたのである.さらに近代英語期に入ると正書法への関心が高まり,綴字上の final e の保存の規則についての議論もかまびすしくなった.

final e の社会化とも呼べそうな上記の英語史上の現象は,興味深いことに,近代ドイツ語にも類例がみられる.高田 (113) によれば,ドイツ語における final e の音声上の消失は,15世紀末に拡大し,16世紀前半に普及したという (ex. im Lande > im Land) .これは,英語よりも数世紀ほど遅い.また,17世紀に e が綴字の上で意図的に復活した様子が,ルター聖書諸版や印刷物の言語的修正から,また文法書にみられる規範的なコメントからも知られる.17世紀中葉までには,e の付加が規範的となっていたようだ.

おもしろいのは,テキストによるが,男性・中世名詞の単数与格の e が aus dem winde や in ihrem hause などのように復活したばかりではなく,人称代名詞や指示代名詞の与格の e が zu ihme や sieder deme のように復活していたり,-ung, -in, -nis の女性接尾辞にも e が付加されて Zuredunge, nachbarinne, gefengnisse のように現われることだ.これらの e は16世紀以降に一般には復活せず,17世紀の文法書でも誤りとされていたのである(高田,p. 114).一種の過剰修正 (hypercorrection) の例といえる.

英語史で final e が問題となるのは,方言にもよるが初期中英語から初期近代英語といってよく,英語史研究者にとっては長々と頭痛の種であり続けてきた.ドイツ語史では問題の開始も遅く,それほど長く続いたものではなかったようだが,正書法などの言語的規範を巻き込んでの問題となった点で,両現象は比較される.屈折語尾の水平化というゲルマン諸語の宿命的な現象に起因する final e の問題は,歴史時代の話題ではあるが,ある意味で比較言語学のテーマとなり得るのではないだろうか

・ 高田 博行 「ドイツの魔女裁判尋問調書(1649年)に記されたことば」『歴史語用論の世界 文法化・待遇表現・発話行為』(金水 敏・高田 博行・椎名 美智(編)),ひつじ書房,2014年.105--32頁.

2015-02-03 Tue

■ #2108. <oa> の綴りの起源 (2) [spelling][orthography][pronunciation][diphthong][gvs]

「#435. <oa> の綴りの起源」 ([2010-07-06-1]) で述べたのとは異なる <oa> の綴字の起源説を紹介する.boat, foam, goal などに現われる2重母音に対応する綴字 <oa> の習慣は,出現したのも定着したのも歴史的には比較的遅く,初期近代英語のことである.近代英語期以降の綴字標準化の歴史は,ほとんどの場合非難の対象にこそなれ,賞賛されることは滅多にないものだが,この <oa> に関しては少し褒めてもよい事情がある.

現代英語において,例えば boot と boat は母音部の発音が異なり,したがって対応する綴字も異なるというのは当たり前のように思われるが,この当たり前が実現されたのは,初期近代英語期に後者の単語を綴るのに <oa> が採用されたそのときだった.というのは,それより前の中英語では,両単語の母音は同様に異なっていたものの,その差異は綴字上反映されていなかったからだ.具体的にいえば,boot, boat に対応する中英語の形態では,発音はそれぞれ [boːt], [bɔːt] であり,長母音が異なっていた.2つの長母音は音韻レベルでも異なっていたので,綴り分けられることがあってもよさそうなものだが,実際にはいずれも <bote> などと綴られるのが普通であり,綴字上の区別は特に一貫していなかった.この語に限らず,中英語の [oː], [ɔː] の2つの長母音は,いずれも <o>, <oo>, <o .. e> などと表記することができ,いわば異音同綴となっていた.

中英語の間は,それでも大きな問題は生じなかった.だが,中英語末期から初期近代英語期にかけて大母音推移 (gvs) が始まると,[oː], [ɔː] の差異は [uː], [oː] (> [oʊ]) の差異へとシフトした.大母音推移の後では音質の差が広がったといってよく,綴字上の区別もつけられるのが望ましいという意識が芽生えたのだろう,狭いほうの母音には <oo> をあてがい,広いほうの母音には <oa> (あるいは <o .. e>)をあてがうという慣習が生まれ,定着した.異なる語であり異なる発音なのだから異なる綴字で表記するという当たり前の状況が,ここでようやく生まれたことになる.

ブルシェ (74) によれば,「<oa> という結合は恐らく <ea> にならって作られ,12?13世紀に出現した」が,「その後 <oa> は消滅し」た.それが,上記のように大母音推移が始まる15世紀に復活し,その後定着することになった.現われては消え,そして再び現われるという <oa> の奇妙な振る舞いは,対応する前舌母音を表記する <ea> の歴史とも,確かに無関係ではないのかもしれない.<ea> については「#436. <ea> の綴りの起源」 ([2010-07-07-1]) も参照.

・ ジョルジュ・ブルシェ(著),米倉 綽・内田 茂・高岡 優希(訳) 『英語の正書法――その歴史と現状』 荒竹出版,1999年.

2015-01-26 Mon

■ #2100. 近代フランス語に基づく「語源的綴字」 [french][spelling][etymological_respelling][lmode]

初期近代英語の語源的綴字に関する話題は,通常,ルネサンス期のラテン語熱の所産であるとして語られる.仰ぎ見るべきお手本は,優に千年以上踏み固められてきたラテン語の綴字であり,英語もフランス語から譲り受けた「崩れた」形ではなく,少しでもラテン語本家の形に近づくべきだ,と.そうしてみると,近代英語は,直前数世紀のあいだ一目おいていたフランス語に追いつき,さらに追い越さんという勢いのなかで,さらなる高みにあるラテン語の威光を目指していたということになる.では,フランス語はもはや英語の綴字に模範を与えるような存在ではなくなっていたということだろうか.例えば,フランス借用語などにおいてフランス語の綴字に基づいた綴りなおしという現象はなかったのだろうか.

ラテン語に基づいた語源的綴字の影で目立たないが,そのような例は後期近代英語期に見られる.「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]) 及び「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]) の記事でみたように,17世紀後半から18世紀にかけては,フランス様式やフランス文化が大流行した時期である.この頃英語へ借用されたフランス単語は,フランス語の綴字と発音のままで受け入れられ現在に至っているものが多いという特徴をもつが,より早い段階に英語へ借用されていたフランス単語が,改めて近代フランス語風に綴りなおされるという例もあった.

例えば,Horobin (134) は,bisket が biscuit へ,blew が blue へ綴りなおされたのは,当時のフランス語綴字が参照されたためとしている.実際には,biscuit は19世紀の綴りなおし,blue は18世紀からの綴じなおしである.ここで起こったことは同時代のフランス語の綴字を参照して綴りなおしたにすぎず,ラテン語の事例にならって「語源的綴字」と呼ぶのは必ずしも正確ではなく,むしろフランス語からの再借用と称しておくべきものかもしれないが,表面的には「語源的綴字」と似た側面があり興味深い.最終的にフランス語式の綴字が採られて定着した例として「#299. explain になぜ <i> があるのか」 ([2010-02-20-1]),「#300. explain になぜ <i> があるのか (2)」 ([2010-02-21-1]) で取り上げた <explain> もあるので,参照されたい.

だが,いかんせん例は少ないように思われる.ほかの手段で調べれば類例がもっと出てくるかもしれないが,そのために調査すべき期間は17世紀後半から19世紀前半くらいまでの間というところか.というのは,近代英語期のフランス語借用の流行期は18世紀がピークであり,世紀末のフランス革命以後は,貴族の威信が下落し,中流階級が台頭してくるにしたがってフランス様式の流行は下火になったからだ.

語源的綴字という実践の背後にある原動力の1つは,流行と威信の言語に,せめて綴定上だけでもあやかりたいと思う憧れの気持ちである.その点においては,初期近代英語のラテン語ベースの語源的綴字も後期近代英語のフランス語ベースの「語源的綴字」も共通している.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow