2021-05-25 Tue

■ #4411. German と Germanic の違い --- ややこしすぎる言語名の問題 [onomastics][khelf_hel_intro_2021][sobokunagimon][german][germanic][comparative_linguistics][terminology][language_myth]

英語にはややこしい民族名,国民名,言語名が多々あります.民族も国民も言語もたいてい複雑な固有の歴史を背負ってきているので,それを表わす語もややこしくなってしまうのは致し方のないことかもしれません.しかし,標題の2語はそれにしても誤解を招きやすい点では最右翼に位置づけられるペアといってよいでしょう.「#4380. 英語のルーツはラテン語でもドイツ語でもない」 ([2021-04-24-1]) で触れたような誤解が生まれるのも無理からぬことです.

言語の呼称としての German は「ドイツ語」を指します.一方,Germanic は比較言語学的に再建された「ゲルマン(祖)語」 (= Proto-Germanic) を指します.形容詞としては,後者は「ゲルマン(祖)語の」あるいは,このゲルマン(祖)語から派生した一群の言語を指して「ゲルマン語派の」ほどを意味します.

「英語史導入企画2021」より今日紹介するコンテンツは,まさにこの2語のややこしさに焦点を当てた,院生による「A Succinct Account of German and Germanic」です.英語による音声コンテンツとなっています.

英和辞典によると German は「ドイツ人,ドイツ語;ドイツの」ほど,Germanic は「ゲルマン(祖)語;ゲルマン系の,ドイツ的な」ほどとなりますが,すでにこの時点で分かりにくいですね.学習者用英英辞典 OALD8 によると,各々およそ次の通りでした.

German

adjective:

from or connected with Germany

noun:

1 [countable] a person from Germany

2 [uncountable] the language of Germany, Austria and parts of Switzerland

Germanic

adjective:

1 connected with or considered typical of Germany or its people

2 connected with the language family that includes German, English, Dutch and Swedish among others

形容詞としては,"connected with Germany" が共通項となっていますし,やはり分かったような分からないような区別です.

両語の区別を理解する上で参考になるのは各語の初出年です.German の初出は,名詞としては1387年より前,形容詞としては1536年で,そこそこ古いといえますが,Germanic はまず形容詞として1539年に初出し,「ゲルマン(祖)語」を意味する名詞としてはさらに遅く1718年のことです.つまり「ゲルマン(祖)語」の語義は,言語学用語としての後付けの語義だと分かります.

後付けであればこそ,後発の強みを活かして誤解を招かない別の用語を選んでもらいたかったところです.いや,実のところ,比較言語学では「ゲルマン祖語」を指すのに Teutonic (cf. 英語 Dutch, ドイツ語 Deutsch) という別の用語を用いる慣習も古くはあったのです.それだけに,紛らわしい Germanic が結局のところ勝利し定着してしまったことは皮肉と言わざるを得ません.

関連して「#3744. German の指示対象の歴史的変化と語源」 ([2019-07-28-1]) と「#864. 再建された言語の名前の問題」 ([2011-09-08-1]) もご一読ください.

(後記 2021/05/26(Wed):今回紹介した音声コンテンツの文章版が「'German' と 'Germanic' についての覚書」として後日公表されましたので,こちらも案内しておきます.)

2021-05-08 Sat

■ #4394. 「疑いの2」の英語史 [khelf_hel_intro_2021][etymology][comparative_linguistics][indo-european][oe][lexicology][loan_word][germanic][italic][latin][french][edd][grimms_law][etymological_respelling][lexicology][semantic_field]

印欧語族では「疑い」と「2」は密接な関係にあります.日本語でも「二心をいだく」(=不忠な心,疑心をもつ)というように,真偽2つの間で揺れ動く心理を表現する際に「2」が関わってくるというのは理解できる気がします.しかし,印欧諸語では両者の関係ははるかに濃密で,語形成・語彙のレベルで体系的に顕在化されているのです.

昨日「英語史導入企画2021」のために大学院生より公開された「疑いはいつも 2 つ!」は,この事実について比較言語学の観点から詳細に解説したコンテンツです.印欧語比較言語学や語源の話題に関心のある読者にとって,おおいに楽しめる内容となっています.

上記コンテンツを読めば,印欧諸語の語彙のなかに「疑い」と「2」の濃密な関係を見出すことができます.しかし,ここで疑問が湧きます.なぜ印欧語族の一員である英語の語彙には,このような関係がほとんど見られないのでしょうか.コンテンツの注1に,次のようにありました.

現代の標準的な英語にはゲルマン語の「2」由来の「疑い」を意味する単語は残っていないが,English Dialect Dictionary Online によればイングランド中西部のスタッフォードシャーや西隣のシュロップシャーの方言で tweag/tweagle 「疑い・当惑」という単語が生き残っている.

最後の「生き残っている」にヒントがあります.コンテンツ内でも触れられているとおり,古くは英語にもドイツ語や他のゲルマン語のように "two" にもとづく「疑い」の関連語が普通に存在したのです.古英語辞書を開くと,ざっと次のような見出し語を見つけることができました.

・ twēo "doubt, ambiguity"

・ twēogende "doubting"

・ twēogendlic "doubtful, uncertain"

・ twēolic "doubtful, ambiguous, equivocal"

・ twēon "to doubt, hesitate"

・ twēonian "to doubt, be uncertain, hesitate"

・ twēonigend, twēoniendlic "doubtful, expressing doubt"

・ twēonigendlīce "perhaps"

・ twēonol "doubtful"

・ twīendlīce "doubtingly"

これらのいくつかは初期中英語期まで用いられていましたが,その後,すべて事実上廃用となっていきました.その理由は,1066年のノルマン征服の余波で,これらと究極的には同根語であるラテン語やフランス語からの借用語に,すっかり置き換えられてしまったからです.ゲルマン的な "two" 系列からイタリック的な "duo" 系列へ,きれいさっぱり引っ越ししたというわけです(/t/ と /d/ の関係についてはグリムの法則 (grimms_law) を参照).現代英語で「疑いの2」を示す語例を挙げてみると,

doubt, doubtable, doubtful, doubting, doubtingly, dubiety, dubious, dubitate, dubitation, dubitative, indubitably

など,見事にすべて /d/ で始まるイタリック系借用語です.このなかに dubious のように綴字 <b> を普通に /b/ と発音するケースと,doubt のように <b> を発音しないケース(いわゆる語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling))が混在しているのも英語史的にはおもしろい話題です (cf. 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])).

このようにゲルマン系の古英語単語が中英語期以降にイタリック系の借用語に置き換えられたというのは,英語史上はありふれた現象です.しかし,今回のケースがおもしろいのは,単発での置き換えではなく,関連語がこぞって置き換えられたという点です.語彙論的にはたいへん興味深い現象だと考えています (cf. 「#648. 古英語の語彙と廃語」 ([2011-02-04-1])).

こうして現代英語では "two" 系列で「疑いの2」を表わす語はほとんど見られなくなったのですが,最後に1つだけ,その心を受け継ぐ表現として be in/of two minds about sb/sth (= to be unable to decide what you think about sb/sth, or whether to do sth or not) を紹介しておきましょう.例文として I was in two minds about the book. (= I didn't know if I liked it or not) など.

2021-04-24 Sat

■ #4380. 英語のルーツはラテン語でもドイツ語でもない [indo-european][language_family][language_myth][latin][german][germanic][comparative_linguistics][khelf_hel_intro_2021]

新年度初めのイベントとして立ち上げた「英語史導入企画2021」では,日々学生から英語史に関するコンテンツがアップされてくる.昨日は院生による「英語 --- English --- とは」が公表された.英語のルーツが印欧祖語にさかのぼることを紹介する,まさに英語史導入コンテンツである.

本ブログを訪れている読者の多くにとっては当前のことと思われるが,英語はゲルマン語派に属する1言語である.しかし,一般には英語がラテン語(イタリック語派の1言語)から生まれたとする誤った理解が蔓延しているのも事実である.ラテン語は近代以降すっかり衰退してきたとはいえ,一種の歴史用語として抜群の知名度を誇っており,同じ西洋の言語として英語と関連があるにちがいないと思われているからだろう.

一方,少し英語史をかじると,英語にはラテン語からの借用語がやたら多いということも聞かされるので,両言語の語彙には共通のものが多い,すなわち共通のルーツをもつのだろう,という実はまったく論理的でない推論が幅を利かせることにもなりやすい.

英語はゲルマン系の言語であるということを聞いたことがあると,もう1つ別の誤解も生じやすい.英語はドイツ語から生まれたという誤解だ.英語でドイツ語を表わす German とゲルマン語を表わす Germanic が同根であることも,この誤解に拍車をかける.

本ブログの読者の多くにとって,上記のような誤解が蔓延していることは信じられないことにちがいない.では,そのような誤解を抱いている人を見つけたら,どのようにその誤解を解いてあげればよいのか.簡単なのは,上記コンテンツでも示してくれたように印欧語系統図を提示して説明することだ.

しかし,誤解の持ち主から,そのような系統図は誰が何の根拠に基づいて作ったものなのかと逆質問されたら,どう答えればよいだろうか.これは実のところ学術的に相当な難問なのである.19世紀の比較言語学者たちが再建 (reconstruction) という手段に訴えて作ったものだ,と仮に答えることはできるだろう.しかし,再建形が正しいという根拠はどこにあるかという理論上の真剣な議論となると,もう普通の研究者の手には負えない.一種の学術上の信念に近いものでもあるからだ.であるならば,「英語のルーツは○○語でなくて△△語だ」という主張そのものも,存立基盤が危ういということにならないだろうか.突き詰めると,けっこう恐い問いなのだ.

「英語史導入企画2021」のキャンペーン中だというのに,小難しい話しをしてしまった.むしろこちらの方に興味が湧いたという方は,以下の記事などをどうぞ.

・ 「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1])

・ 「#371. 系統と影響は必ずしも峻別できない」 ([2010-05-03-1])

・ 「#862. 再建形は実在したか否か (1)」 ([2011-09-06-1])

・ 「#863. 再建形は実在したか否か (2)」 ([2011-09-07-1])

・ 「#2308. 再建形は実在したか否か (3)」 ([2015-08-22-1])

・ 「#864. 再建された言語の名前の問題」 ([2011-09-08-1])

・ 「#2120. 再建形は虚数である」 ([2015-02-15-1])

・ 「#3146. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (1)」 ([2017-12-07-1])

・ 「#3147. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (2)」 ([2017-12-08-1])

・ 「#3148. 言語における「遺伝的関係」の基本単位は個体か種か?」 ([2017-12-09-1])

・ 「#3149. なぜ言語を遺伝的に分類するのか?」 ([2017-12-10-1])

・ 「#3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1)」 ([2017-08-03-1])

・ 「#3021. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (2)」 ([2017-08-04-1])

2021-03-20 Sat

■ #4345. 古英語期までの現在分詞語尾の発達 [oe][germanic][indo-european][etymology][suffix][participle][i-mutaton][grimms_law][verners_law][verb][sound_change]

昨日の記事「#4344. -in' は -ing の省略形ではない」 ([2021-03-19-1]) で現在分詞語尾の話題を取り上げた.そこで簡単に歴史を振り返ったが,あくまで古英語期より後の発達に触れた程度だった.今回は Lass (163) に依拠して,印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語を経て古英語に至るまでの形態音韻上の発達を紹介しよう.

The present participle is morphologically the same in both strong and weak verbs in OE: present stem (if different from the preterite) + -ende (ber-ende, luf-i-ende. etc.). All Gmc dialects have related forms: Go -and-s, OIc -andi, OHG -anti. The source is an IE o-stem verbal adjective, of the type seen in Gr phér-o-nt- 'bearing', with a following accented */-í/, probably an original feminine ending. This provides the environment for Verner's Law, hence the sequence */-o-nt-í/ > */-ɑ-nθ-í/ > */-ɑ-nð-í/, with accent shift and later hardening */-ɑ-nd-í/, then IU to /-æ-nd-i/, and finally /-e-nd-e/ with lowering. The /-i/ remains in the earliest OE forms, with are -ændi, -endi.

様々な音変化 (sound_change) を経て古英語の -ende にたどりついたことが分かる.現在分詞語尾は,このように音形としては目まぐるしく変化してきたようだが,基体への付加の仕方や機能に関していえば,むしろ安定していたようにみえる.この安定性と,同根語が印欧諸語に広くみられることも連動しているように思われる.

また,音形の変化にしても,確かに目まぐるしくはあるものの,おしなべて -nd- という子音連鎖を保持してきたことは注目に値する.これはもともと強勢をもつ */-í/ が後続したために,音声的摩耗を免れやすかったからではないかと睨んでいる.また,この語尾自体が語幹の音形に影響を与えることがなかった点にも注意したい.同じ分詞語尾でも,過去分詞語尾とはかなり事情が異なるのだ.

古英語以降も中英語期に至るまで,この -nd- の子音連鎖は原則として保持された.やがて現在分詞語尾が -ing に置換されるようになったが,この新しい -ing とて,もともとは /ɪŋɡ/ のように子音連鎖をもっていたことは興味深い.しかし,/ŋɡ/ の子音連鎖も,後期中英語以降は /ŋ/ へと徐々に単純化していき,今では印欧祖語の音形にみられた子音連鎖は(連鎖の組み合わせ方がいかようであれ)標準的には保持されていない(cf. 「#1508. 英語における軟口蓋鼻音の音素化」 ([2013-06-13-1]),「#3482. 語頭・語末の子音連鎖が単純化してきた歴史」 ([2018-11-08-1])).

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-08-08 Sat

■ #4121. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版 [hellog-radio][sobokunagimon][hel_education][personal_pronoun][case][germanic]

hellog ラジオ版の第14回は,英語初学者から寄せられた素朴な疑問です.人称代名詞において所有格と目的格はおよそ異なる形態をとりますが,女性単数の she に関してのみ her という同一形態が用いられます.これでは学ぶのに混乱するのではないか,という疑問かと思います.

同一形態でありながら2つ異なる機能を担うというのは,一見すると確かに混乱しそうですが,実際上,それで問題となることはほとんどありません.主格と目的格の形態で考えてみれば,you と it は同一形態をとっていますが,それで混乱したということは聞きません.

しかも,英語の歴史を振り返ってみれば,異なる機能にもかかわらず同一形態をとるようになったという変化は日常茶飯でした.例えば現代の人称代名詞の「目的格」は,もともとは対格と与格という別々の形態・機能を示していたものが,歴史の過程で同一形態に収斂してしまった結果の姿です.また,古い英語では2人称代名詞は単数と複数とで形態が区別されていましたが,近代英語以降に you に合一してしまったという経緯があります(cf. 「#3099. 連載第10回「なぜ you は「あなた」でもあり「あなたがた」でもあるのか?」」 ([2017-10-21-1])).もしこのような変化が本当に深刻な問題だったならば,現代英語は問題だらけの言語ということになってしまいますが,現代英語は目下世界中でまともに運用されているようです.

さらに標準英語から離れて英語の方言に目を移せば,主格 she の代わりに所有格・目的格の形態に対応する er を使用する方言も確認されます(cf. 「#793. she --- 現代イングランド方言における異形の分布」 ([2011-06-29-1]),「#3502. pronoun exchange」 ([2018-11-28-1])).日々そのような方言を用いて何ら問題なく生活している話者が当たり前のようにいるわけです.

物事を構造的にとらえる習慣のついている現代人にとって,言語も体系である以上,機能が異なれば形態も異なるはずだし,形態が異なれば機能も異なるはずだと考えるのは自然です.しかし,言語も歴史のなかで複雑な変化に揉まれつつ現在の姿になっているわけですので,必ずしも表面的にきれいな構造を示していないことも多いのです.

今回の疑問は,実に素朴でありながらも,実は2000年という長い時間軸を念頭にアプローチすべき問題であることを教えてくれる貴重な問いだと思います.

この問題とその周辺については,##4080,3099,793,3502の記事セットをご覧ください.

2020-06-28 Sun

■ #4080. なぜ she の所有格と目的格は her で同じ形になるのですか? [sobokunagimon][personal_pronoun][case][germanic]

英語教育現場より寄せてもらった素朴な疑問です.確かに他の人称代名詞を考えると,すべて所有格と目的格の形態が異なっています.my/me, your/you, his/him, its/it, our/us, their/them のとおりです.名詞についても所有格と目的格(=通格)は boy's/boy, Mary's/Mary のように原則として異なります.つまり,3人称女性単数代名詞 she は,所有格と目的格の形態が同形となる点で,名詞類という広いくくりのなかでみてもユニークな存在なのです.標題の素朴な疑問は,きわめて自然な問いということになります.

この問いに一言で答えるならば,もともとは異なった形態をとっていたものが,後の音変化の結果,たまたま同形に合一してしまった,ということになります.古い時代の音変化のなせるわざということです.

千年以上前に話されていた古英語にさかのぼってみましょう.her は,すでに当時より,所有格(当時の「属格」)と目的格(当時の「与格」)は hi(e)re という同じ形態を示していました.ということは,この素朴な疑問は英語史の枠内にとどまっていては解決できないことになります.

そこで,古英語よりも古い段階の言語の状態を反映しているとされる英語の仲間言語,すなわちゲルマン語派の諸言語の様子を覗いてみましょう.古サクソン語や古高地ドイツ語では,3人称女性単数代名詞の属格は ira,与格は iru であり,微妙ながらも形態が区別されていました.古ノルド語でも属格は hennar, 与格は henne と異なっていましたし,ゴート語でも同様で属格は izōs, 与格は izai でした.

つまり,古英語よりも古い段階では,3人称女性単数代名詞の属格と与格は,他の代名詞の場合と同様に,区別された形態をとっていたと考えられます.しかし,区別されていたとはいえ語尾の僅かな違いによって区別されていたにすぎず,その部分が弱く発音されてしまえば,区別がすぐにでも失われてしまう可能性をはらんでいました.そして,実際にそれが古英語までに起こってしまっていたのです.

このようにみてくると,現代英語の my/me や your/you 辺りも互いに似通っているので,危ういといえば危ういのかもしれません.実際,速い発音では合一していることも多いでしょう.her に関しては,その危険の可能性が他よりも早い段階で現実化してしまったにすぎません.名詞類全体のなかでも特異な,仲間はずれ的な存在となってしまいましたが,歴史の偶然のたまものですから,彼女のことを優しく見守ってあげましょう.

2020-06-02 Tue

■ #4054. 与作は木を切る hew, hay, hoe?♪ [etymology][youtube][germanic][indo-european][cognate]

昨日の記事「#4053. 花粉症,熱はないのに hay fever?」 ([2020-06-01-1]) で hay fever の疑問を取り上げました.なぜ花粉症に「熱」が関係するのかは未解決のままですが,調べる過程で素晴らしい副産物を獲得しました.標題の3語のみごとな語源的共通性です.

hay (干し草)は古英語にも hēġ, hīeġ として現われる古い語で「切られた/刈られた草」を意味しました.「(斧・剣などで)切る」という動詞は hēawan としてあり,これが現代英語の hew (たたき切る,切り倒す)に連なっています.一方,切る道具としての hoe 「根掘り,つるはし,くわ」は,古英語にこそ現われませんが,古高地ドイツ語から古仏語に入った houe が中英語期に借用されたもので,やはりゲルマン祖語の語根に遡ります.ゲルマン祖語の動詞として *χawwan が再建されています.ゲルマン語根からさらに遡れば,印欧祖語の語根 *kau- (to hew, strike) にたどり着きます.上記の3語は母音こそ変異・変化してきましたが,源は1つということになります.

to hew hay (干し草を刈る)という表現もあるので,to hew hay with a hoe という表現も夢ではありません.となれば,思い出さずにいられないのがサブちゃんの名曲です.北島三郎「与作」に合わせて「ひゅーへいホウ」と歌ってみましょう.

それにしても,語源的にうまくできた歌詞ですね.

2020-04-13 Mon

■ #4004. 古英語の3人称代名詞の語頭の h [h][oe][personal_pronoun][indo-european][germanic][etymology][paradigm][number][gender]

古英語の3人称代名詞の屈折表について「#155. 古英語の人称代名詞の屈折」 ([2009-09-29-1]) でみたとおりだが,単数でも複数でも,そして男性・女性・中性をも問わず,いずれの形態も h- で始まる.共時的にみれば,古英語の h- は3人称代名詞マーカーの機能を果たしていたといってよいだろう.ちょうど現代英語で th- が定的・指示的な語類のマーカーであり,wh- が疑問を表わす語類のマーカーであるのと同じような役割だ.

非常に分かりやすい特徴ではあるが,皮肉なことに,この特徴こそが中英語にかけて3人称代名詞の屈折体系の崩壊と再編成をもたらした元凶なのである.古英語では,h- に続く部分の母音等の違いにより性・数・格をある程度区別していたが,やがて屈折語尾の水平化が生じると,性・数・格の区別が薄れてしまった.たとえば古英語の hē (he), hēo (she), hīe (they) が,中英語では(方言にもよるが)いずれも hi などの形態に収斂してしまった.h- そのものは変化しなかったために,かえって混乱を来たすことになったわけだ.かつては「非常に分かりやすい特徴」だった h- が,むしろ逆効果となってしまったことになる.

そこで,この問題を解決すべく再編成のメカニズムが始動した.h- ではない別の子音を語頭にもつ she が女性単数主格に,やはり異なる子音を語頭にもつ they が複数主格に進出し,後期中英語までに古形を置き換えたのである(これらに関する個別の問題については「#713. "though" と "they" の同音異義衝突」 ([2011-04-10-1]),「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1]),「#974. 3人称代名詞の主格形に作用した異化」 ([2011-12-27-1]),「#975. 3人称代名詞の斜格形ではあまり作用しなかった異化」 ([2011-12-28-1]),「#1843. conservative radicalism」 ([2014-05-14-1]),「#2331. 後期中英語における3人称複数代名詞の段階的な th- 化」 ([2015-09-14-1]) を参照).

さて,古英語における h- は共時的には3人称代名詞マーカーだったと述べたが,通時的にみると,どうやら単数系列の h- と複数系列の h- は起源が異なるようだ.つまり,h- は古英語期までに結果的に「非常に分かりやすい特徴」となったにすぎず,それ以前には両系列は縁がなかったのだという.Lass (141) を参照した Marsh (15) は,単数系列の h- は印欧祖語の直示詞 *k- にさかのぼり,複数系列の h- は印欧祖語の指示代名詞 *ei- ? -i- にさかのぼるという.後者は前者に基づく類推 (analogy) により,後から h- を付け足したということらしい.長期的にみれば,この類推作用は古英語にかけてこそ有用なマーカーとして恩恵をもたらしたが,中英語にかけてはむしろ迷惑な副作用を生じさせた,と解釈できるかもしれない.

なお,上で述べてきたことと矛盾するが「#467. 人称代名詞 it の語頭に /h/ があったか否か」 ([2010-08-07-1]) という議論もあるのでそちらも参照.

・ Marsh, Jeannette K. "Periods: Pre-Old English." Chapter 1 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1--18.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2020-04-12 Sun

■ #4003. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化 (2) [adjective][inflection][oe][germanic][indo-european][comparative_linguistics][grammaticalisation][paradigm]

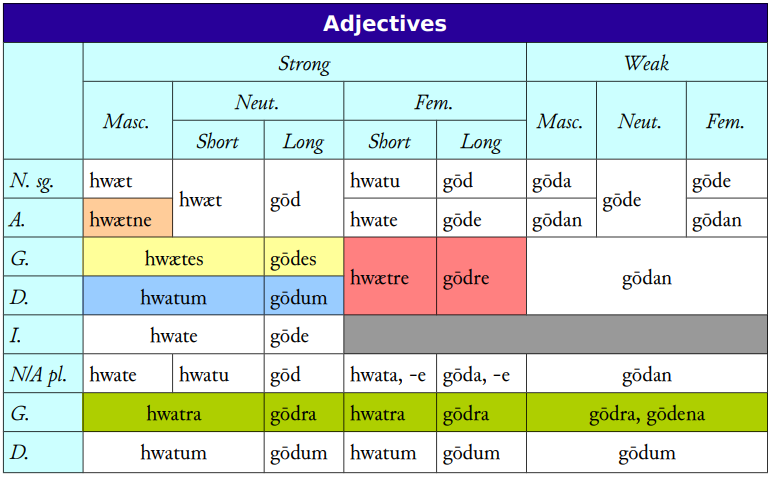

現代英語にはみられないが,印欧語族の多くの言語では形容詞 (adjective) に屈折 (inflection) がみられる.さらにゲルマン語派の諸言語においては,形容詞屈折に関して,統語意味論的な観点から強変化 (strong declension) と弱変化 (weak declension) の2種の区別がみられる(各々の条件については「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) を参照).このような強弱の区別は,ゲルマン語派の著しい特徴の1つとされており,比較言語学的に興味深い(cf. 「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1])).

英語では,古英語期にはこの区別が明確にみられたが,中英語期にかけて屈折語尾の水平化が進行すると,同区別はその後期にかけて失われていった(cf. 「#688. 中英語の形容詞屈折体系の水平化」 ([2011-03-16-1]),「#2436. 形容詞複数屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由」 ([2015-12-28-1]) ).現代英語は,形容詞の強弱屈折の区別はおろか,屈折そのものを失っており,その分だけゲルマン語的でも印欧語的でもなくなっているといえる.

古英語における形容詞の強変化と弱変化の屈折を,「#250. 古英語の屈折表のアンチョコ」 ([2010-01-02-1]) より抜き出しておこう.

では,なぜ古英語やその他のゲルマン諸語には形容詞の屈折に強弱の区別があるのだろうか.これは難しい問題だが,屈折形の違いに注目することにより,ある種の洞察を得ることができる.強変化屈折パターンを眺めてみると,名詞強変化屈折と指示代名詞屈折の両パターンが混在していることに気付く.これは,形容詞がもともと名詞の仲間として(強変化)名詞的な屈折を示していたところに,指示代名詞の屈折パターンが部分的に侵入してきたものと考えられる(もう少し詳しくは「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) を参照).

一方,弱変化の屈折パターンは,特徴的な n を含む点で弱変化名詞の屈折パターンにそっくりである.やはり形容詞と名詞は密接な関係にあったのだ.弱変化名詞の屈折に典型的にみられる n の起源は印欧祖語の *-en-/-on- にあるとされ,これはラテン語やギリシア語の渾名にしばしば現われる (ex. Cato(nis) "smart/shrewd (one)", Strabōn "squint-eyed (one)") .このような固有名に用いられることから,どうやら弱変化屈折は個別化の機能を果たしたようである.とすると,古英語の形容詞弱変化屈折を伴う se blinda mann "the blind man" という句は,もともと "the blind one, a man" ほどの同格的な句だったと考えられる.それがやがて文法化 (grammaticalisation) し,屈折という文法範疇に組み込まれていくことになったのだろう.

以上,Marsh (13--14) を参照して,なぜゲルマン語派の形容詞に強弱2種類の屈折があるのかに関する1つの説を紹介した.

・ Marsh, Jeannette K. "Periods: Pre-Old English." Chapter 1 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1--18.

2020-04-04 Sat

■ #3995. Ruthwell Cross の "on rodi" [ruthwell_cross][oe][dative][case][syncretism][germanic][inscription][manuscript]

Dumfriesshire の Ruthwell Cross は,古英詩 The Dream of the Rood の断片がルーン文字で刻まれた有名な石碑である.8世紀初頭のものと考えられている.そこに古英語アルファベットで転字すると "kristwæsonrodi" と読める文字列がある.分かち書きをすれば "krist wæs on rodi" (Crist was on the rood) となる.古英語の文法によれば,最後の名詞は前置詞 on に支配されており,本来であれば与格形 rode となるはずだが,実際には不明の形態 rodi が用いられているので,文献学上の問題とされてきた.10世紀の Vercelli Book に収められている同作品の対応箇所では,期待通りに on rode とあるだけに,なおさら rodi の形態が問題となってくる.

原文の書き間違い(彫り間違いというべきか)ではないかという意見もあれば,他の名詞クラスの形態からの類推ではないかという説を含めて積極的に原因を探ろうとする試みもあった.しかし,改めてこの問題を取り上げた Lass は,別の角度から rodi が十分にあり得る形態であることを力説した.昨日の記事「#3994. 古英語の与格形の起源」 ([2020-04-03-1]) でも引用したように,Lass はゲルマン諸語の格の融合 (syncretism) の過程は著しく複雑だったと考えている.とりわけ Ruthwell Cross にみられるような最初期の古英語文献において,後代の古典的古英語文法からは予測できない形態が現われるということは十分にあり得るし,むしろないほうがおかしいと主張する.現代の研究者は,そこから少しでも逸脱した形態はエラーと考えてしまうまでに正典化された古英語文法の虜になっており,現実の言語の変異や多様性に思いを馳せることを忘れてしまっているのではないかと厳しい口調で論じている(Lass (400) はこの姿勢を "classicism" と呼んでいる).この問題に関する Lass (401) の結論は次の通り.

A final verdict then on rodi: not only does it not stand in need of special 'explanation', we ought to be very surprised if it or something like it didn't turn up in the early materials, and probably assume that the paucity of such remains is a function of the paucity of data. The fact that a given declension will show perhaps both -i and -æ datives (or even -i and -æ and -e) in very early inscriptions and glosses is a matter of profound historical interest. We have as it were caught a practicing bricoleur in the act, experimenting with different ways of cobbling together a noun paradigm out of the materials at hand. Morphological change is not neogrammarian, declensions are not stable or water-tight (they leak, as Sapir said of grammars), and --- most important --- the reconstruction of a new system out of the disjecta membra of an old and more complex one is bound to be marked by false starts and afterthoughts, and therefore a certain amount of 'irregularity'. It is also bound to take time, and the shape we encounter will depend on where in its trajectory of change we happen to catch it. Systems in process of reformation will be messy until a final mopping-up can be effected.

昨日の記事の締めの言葉を繰り返せば,言語は pure でも purist でもない.

・ Lass, Roger. "On Data and 'Datives': Ruthwell Cross rodi Again." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 92 (1991): 395--403.

2020-04-03 Fri

■ #3994. 古英語の与格形の起源 [oe][dative][germanic][indo-european][case][syncretism][instrumental][suppletion][exaptation]

昨日の記事「#3993. 印欧語では動詞カテゴリーの再編成は名詞よりも起こりやすかった」 ([2020-04-02-1]) で,古英語の名詞の与格 (dative) の起源に触れた.前代の与格,奪格,具格,位格という,緩くいえば場所に関わる4つの格が融合 (syncretism) して,新たな「与格」として生まれ変わったということだった.これについて,Lass (Old English 128--29) による解説を聞いてみよう.

The transition from late IE to PGmc involved a collapse and reformation of the case system; nominative, genitive and accusative remained more or less intact, but all the locational/movement cases merged into a single 'fourth case', which is conventionally called 'dative', but in fact often represents an IE locative or instrumental. This codes pretty much all the functions of the original dative, locative, ablative and instrumental. A few WGmc dialects do still have a distinct instrumental sg for some noun classes, e.g. OS dag-u, OHG tag-u for 'day' vs. dat sg dag-e, tag-e; OE has collapsed both into dative (along with locative, instrumental and ablative), though some traces of an instrumental remain in the pronouns . . .

格の融合の話しがややこしくなりがちなのは,融合する前に区別されていた複数の格のうちの1つの名前が選ばれて,融合後に1つとなったものに割り当てられる傾向があるからだ.古英語の場合にも,前代の与格,奪格,具格,位格が融合して1つになったというのは分かるが,なぜ新たな格は「与格」と名付けられることになったのだろうか.形態的にいえば,新たな与格形は古い与格形を部分的には受け継いでいるが,むしろ具格形の痕跡が色濃い.

具体的にいえば,与格複数の典型的な屈折語尾 -um は前代の具格複数形に由来する.与格単数については,ゲルマン諸語を眺めてみると,名詞のクラスによって起源問題は複雑な様相を呈していが,確かに前代の与格形にさかのぼるものもあれば,具格形や位格形にさかのぼるものもある.古英語の与格単数についていえば,およそ前代の与格形にさかのぼると考えてよさそうだが,それにしても起源問題は非常に込み入っている.

Lass は別の論考で新しい与格は "local" ("Data" 398) とでも呼んだほうがよいと提起しつつ,ゲルマン祖語以後の複雑な経緯をざっと説明してくれている ("Data" 399).

. . . all the dialects have generalized an old instrumental in */-m-/ for 'dative' plural (Gothic -am/-om/-im, OE -um, etc. . . ). But the 'dative' singular is a different matter: traces of dative, locative and instrumental morphology remain scattered throughout the existing materials.

要するに,古英語やゲルマン諸語の与格は,形態の出身を探るならば「寄せ集め所帯」といってもよい代物である.寄せ集め所帯ということであれば「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]) で解説した be 動詞の状況と異ならない.be 動詞の様々な形態も,4つの異なる語根から取られたものだからだ.また,各種の補充法 (suppletion) の例も同様である.言語は pure でも purist でもない.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

・ Lass, Roger. "On Data and 'Datives': Ruthwell Cross rodi Again." Neuphilologische Mitteilungen 92 (1991): 395--403.

2020-03-18 Wed

■ #3978. 区別しておくべき2つの "Old Norse" [old_norse][terminology][germanic][variety]

英語史において「古ノルド語」あるいは "Old Norse" (old_norse) という言語名を使うときに注意しなければならないのは,この名前が2つの異なる指示対象をもち得るということだ.

1つは,北ゲルマン語群のうち現存する最古の資料としての古アイスランド語(12世紀以降)を,同語群の代表として指し示す用法.もう1つは,とりわけ英語史研究の文脈において,8世紀半ばから11世紀にかけて英語を母語とするアングロサクソン人が,主に北東イングランドで接触したヴァイキングたちの母語を指す用法である.

この2つの指示対象は,まずもって時期が少なくとも1世紀以上異なる.また,空間的にも前者はアイスランド,後者は北ゲルマン語群のなかで西と東の両グループにまたがるものの,原則としてスカンジナビア半島である.OED の新版ではこの用語上の混乱を避けるために,前者を(文献があるという点で)具体的に "Old Icelandic" と,後者を(文献がないという点で)やや抽象的に "early Scandinavian" と呼び分けているようだ.この厳密な使い分けは確かに正確で便利だが,要は用語上の問題にすぎないので,文脈さえ明確であれば,いずれもこれまで通り "Old Norse" と呼んでおいても差し支えはない.ただし,区別を意識しておく必要はあるだろう.

Durkin (175) がこの問題を明示的に指摘していた.私自身はこれまで2つの "Old Norse" を一応のところ区別していたと思うが,明示的に区別すべしという議論を聞いてハッとした.

One important, albeit slightly arcane, initial question concerns terminology. Traditionally, the term 'Old Norse' has been used to denote two different things: (i) the language of the earliest substantial documents in any Scandinavian language, namely the rich literature largely preserved in Icelandic manuscripts dating from the twelfth century and (mostly) later; and (ii) the language that was in contact with English in the British Isles. In fact this is somewhat misleading, since English was in contact with the ancestor varieties of both West Norse (Norwegian and Icelandic) and East Norse (Danish and Swedish), but at a time earlier than our earliest substantial surviving documents for any of the Scandinavian languages, and at a time when the differences between West and East Norse were still very slight. Thus it is only rarely that English words can be attributed to either West or East Norse influence with any confidence. In this book I follow the terminology used in the new edition of the OED, using 'early Scandinavian' as a catch-all for the early West Norse and East Norse varieties which were in contact with English, and distinguishing this from 'Old Icelandic' denoting the language of the early Icelandic texts, and from 'Old Norwegian', 'Old Danish', 'Old Swedish' denoting the oldest literary records of each of these languages.

言語名というのはときにトリッキーで,注意しておかなければならないケースがある.関連して「#3558. 言語と言語名の記号論」 ([2019-01-23-1]),「#864. 再建された言語の名前の問題」 ([2011-09-08-1]) なども参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2020-02-12 Wed

■ #3943. 強勢のある語末音節の rhyme は少なくとも -VC か -VV で構成されていなければならない [phonology][syllable][germanic]

英単語の音節構造には厳しい制約がある.a, the などの弱形をもつ機能語を除き,強勢のある語末音節の rhyme が少なくとも2モーラで構成されていなければならないというものだ.ここでいう rhyme とは音節構造の単位のことで,「#1563. 音節構造」 ([2013-08-07-1]),「#3715. 音節構造に Rhyme という単位を認める根拠」 ([2019-06-29-1]) で説明した,音節末の「母音(+子音)」の部分を指す.

この部分が2モーラなければならないということは,要するに最低条件として「短母音+1子音」 (VC) か「長母音/2重母音」 (VV) のいずれかでなければならないということだ.音節の頭 (onset) に子音があるかどうかは問わないが,問題の部分が「短母音」のみで終わるような単語は許されないということになる.つまり「短母音」だけの強勢をもつ語末音節はあり得ないし,「子音+短母音」もダメである.確かに機能語の弱形を除けば /ɪ/, /ɛ/, /æ/, /ɑ/, /ɒ/, /ɔ/, /ʊ/, /ʌ/, /ə/ のような語はないし,これらに何らかの頭子音を加えただけの語も存在しない.英語において,この音節構造上の制約は非常に強い(例外については「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1]),「#3776. 機能語の強音と弱音 (2)」 ([2019-08-29-1]) を参照).

実はこの性質は北西ゲルマン語群に共通のものである.ゲルマン語派の発達の North-West Germanic と呼ばれる段階で,この音節構造の型が獲得された.獲得の理由は明らかではないが,いずれにせよ短母音のみで終わる強勢をもつ語末音節は御法度となった.歴史的に短母音で終わっていた場合には,原則として長母音化するという形でルールに合わせることになったのである.関連して Minkova (70) を引用する.

. . . we noted the absence of word-final stressed short, lax, non-peripheral vowels [ɪ ɛ æ ʊ ʌ] in PDE; words such as *se with [-ɛ], *decrí with [-ɪ], *bru with [-ʊ] are ill-formed. This constraint on the shape of the final stressed syllable in English can be traced back to OE and even earlier. In all North-West Germanic languages the final vowels of lexical monosyllables became uniformly long, that is, they were lengthened if the original vowel was short. In some instances the long vowel appears to be a compensation for the loss of PrG final /-z/: PrG */hwaz/ > OE hwā 'who', PrG /wiz/, OE wē 'we'. Lengthening without loss of a syllable coda is attested in OE nū 'now', Goth. nu, OE swā 'so', Goth. swa; in this second set the process is evidently driven by the preference for co-occurrence of stress and syllable weight.

この制約は,1音節語に関する正書法上の「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]) にも,間接的ながら一定の影を落としているにちがいない.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

2020-02-11 Tue

■ #3942. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への主要な母音変化 [vowel][indo-european][germanic][sound_change][centralisation]

標題は,印欧祖語の形態から英単語の語源を導こうとする上で重要な知識である.上級者は,語源辞書や OED の語源欄を読む上で,これを知っているだけでも有用.Minkova (68--69) より.

| a | ──┐ | PIE *al- 'grow', Lat. aliment, Gmc *alda 'old' | |

| ├── | a | ||

| o | ──┘ | PIE *ghos-ti- 'guest', Lat. hostis, Goth. gasts | |

| ā | ──┐ | PIE *māter, Lat. māter, OE mōder 'mother' | |

| ├── | ō | ||

| ō | ──┘ | PIE *plōrare 'weep', OE flōd 'flood' | |

| i | ──┐ | PIE *tit/kit 'tickle', Lat. titillate, ME kittle | |

| ├── | i | ||

| e | ──┘ | Lat. ventus, OE wind 'wind', Lat. sedeo, Gmc *sitjan 'sit' |

たとえば,印欧祖語で *māter "mother" は ā の長母音をもっていたが,これがゲルマン祖語までに ō に化けていることに注意.実際,古英語でも mōdor として現われている.この長母音が後に o へと短化し,さらに一段上がって u となり,最終的に中舌化するに至って現代の /ʌ/ にたどりついた.英語の母音は,5,6千年の昔から,概ね規則正しく変化し続けて現行のものになっているのである.

・ Minkova, Donka. A Historical Phonology of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2014.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-10-13 Sun

■ #3821. Old Saxon からの借用語 [loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][old_saxon][germanic][dutch][flemish][german][oe][germanic]

英語史において,英語と同じ西ゲルマン語群の姉妹言語である Old Saxon の存在感は薄い.しかし,ゼロではない.昨日の記事「#3819. アルフレッド大王によるイングランドの学問衰退の嘆き」 ([2019-10-11-1]) で触れた,アルフレッド大王の教育改革に際して,John という名の古サクソン人が補佐を務めていたという記録がある.また,Genesis B として知られる古英詩には,9世紀の Old Saxon から翻訳された1節が含まれていることも知られている.

Genesis B には,hearra (lord), sima (chain), landscipe (region), heodæg (today) を含む少数の Old Saxon に由来するとおぼしき語が確認される.いずれも後代に受け継がれなかったという点では,英語史上の意義は小さいといわざるを得ない.しかし,必要とあらばありとあらゆる単語を多言語から借りるという,後に発達する英語の雑食的な特徴が,古英語期にすでに現われていたということは銘記しておいてよい (Crystal 27) .

一般に,英語史において「遺伝的」関係が近い西ゲルマン語群からの借用語は多くはない.遺伝的関係が近いのであれば,現実の言語接触も多かったはずではないかと想像されるが,そうでもない.たとえば,(高地)ドイツ語からの借用語は「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]),「#2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から」 ([2016-06-30-1]) でみたように,全体としては目立たない.それなりの規模で英語に影響を与えたといえるのは,オランダ語やフラマン語くらいだろう.これらの低地諸語からの語彙的影響については,「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]),「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]),「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1]),「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]),「#3436. イングランドと低地帯との接触の歴史」 ([2018-09-23-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2019.

2019-10-13 Sun

■ #3821. Old Saxon からの借用語 [loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][old_saxon][germanic][dutch][flemish][german][oe][germanic]

英語史において,英語と同じ西ゲルマン語群の姉妹言語である Old Saxon の存在感は薄い.しかし,ゼロではない.昨日の記事「#3819. アルフレッド大王によるイングランドの学問衰退の嘆き」 ([2019-10-11-1]) で触れた,アルフレッド大王の教育改革に際して,John という名の古サクソン人が補佐を務めていたという記録がある.また,Genesis B として知られる古英詩には,9世紀の Old Saxon から翻訳された1節が含まれていることも知られている.

Genesis B には,hearra (lord), sima (chain), landscipe (region), heodæg (today) を含む少数の Old Saxon に由来するとおぼしき語が確認される.いずれも後代に受け継がれなかったという点では,英語史上の意義は小さいといわざるを得ない.しかし,必要とあらばありとあらゆる単語を多言語から借りるという,後に発達する英語の雑食的な特徴が,古英語期にすでに現われていたということは銘記しておいてよい (Crystal 27) .

一般に,英語史において「遺伝的」関係が近い西ゲルマン語群からの借用語は多くはない.遺伝的関係が近いのであれば,現実の言語接触も多かったはずではないかと想像されるが,そうでもない.たとえば,(高地)ドイツ語からの借用語は「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]),「#2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から」 ([2016-06-30-1]) でみたように,全体としては目立たない.それなりの規模で英語に影響を与えたといえるのは,オランダ語やフラマン語くらいだろう.これらの低地諸語からの語彙的影響については,「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]),「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]),「#2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計」 ([2016-07-25-1]),「#3435. 英語史において低地諸語からの影響は過小評価されてきた」 ([2018-09-22-1]),「#3436. イングランドと低地帯との接触の歴史」 ([2018-09-23-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2019.

2019-09-05 Thu

■ #3783. 大陸時代のラテン借用語 pound, kettle, cheap [latin][loan_word][germanic][etymology][history]

英語(およびゲルマン諸語)が大陸時代にラテン語から借用したとされる単語がいくつかあることは,「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]) などで紹介してきた.ローマ時代後期の借用語とされる pound, kettle, cheap; street, wine, pit, copper, pin, tile, post (wooden shaft), cup (Durkin 55) などの例が挙げられるが,そのうち pound, kettle, cheap について Durkin (72--75) に詳しい解説があるので,それを要約したい.

古英語 pund は,Old Frisian pund, Old High German phunt, Old Icelandic pund, Old Swedish pund, Gothic pund などと広くゲルマン諸語に文証される.しかし諸言語に共有されているというだけでは,早期の借用であることの確証にはならない.ここでのポイントは,これらの諸言語に意味変化が共有されていることだ.つまり,いずれも重さの単位としての「ポンド」の意味を共有している.これはラテン語の lībra pondō (a pound by weight) という句に由来し,句の意味は保存しつつ,形態的には第2要素のみを取ったことによるだろう.交易において正確な重量測定が重要であることを物語る早期借用といえる.

次に古英語 ċ(i)etel もゲルマン諸語に同根語が確認される (ex. Old Saxon ketel, Old High German kezzil, Old Icelandic ketill, Gothic katils) .古英語形は子音が口蓋化を,母音が i-mutation を示していることから,早期の借用とみてよい.ラテン語 catīnus は「食器」を意味したが,ゲルマン諸語ではそこから発達した「やかん」の意味が共有されていることも,早期の借用を示唆する.ただし,現代英語の kettle という形態は,ċ(i)etel からは直接導くことができない.後の時代に,語頭子音に k をもつ古ノルド語の同根語からの影響があったのだろう.

ラテン語 caupō (small tradesman, innkeeper) に由来するとされる古英語 ċēap (purchase or sale, bargain, business, transaction, market, possessions, livestock) とその関連語も,しばしば大陸時代の借用とみられている.現代の形容詞 cheap は "good cheap" (good bargain) という句の短縮形が起源とされる.ゲルマン諸語の同根語は,Old Frisian kāp, Middle Dutch coop, Old Saxon kōp, Old High German chouf, Old Icelandic kaup など.動詞化した ċēapian (to buy and sell, to make a bargain, to trade) や ċȳpan (to sell) もゲルマン諸語に同根語がある.ほかに ċȳpa, ċēap (merchant, trader) を始めとして,ċēapung, ċȳping (trade, buying and selling, market, market place) や ċȳpman, ċȳpeman (merchant, trader) などの派生語・複合語も多数みつかる.この語については「#1460. cheap の語源」 ([2013-04-26-1]) も参照.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2019-08-12 Mon

■ #3759. 周縁部から始まった俗語書記文化 [celtic][anglo-saxon][germanic][latin][literature][writing][geography][geolinguistics]

中世前期のヨーロッパにおける俗語書記文化の発達は,周縁部から順に始まったようにみえる.ラテン語ではなく俗語 (vernacular) で書かれた文学が現われるのは,フランス語では1098年頃の『ローランの歌』,ドイツ語では13世紀の『ニーベルンゲンの歌』というタイミングだが,英語ではずっと早く700年頃とされる『ベオウルフ』が最初である.

地理的にさらに周縁に位置するアイルランド語については,現存する最古の文書は1106年頃の『ナ・ヌイドレ書』や1160年頃の『ラグネッヘ書』とされるが,その起源は6世紀にまでさかのぼるという.6世紀のダラーン・フォルギルによる「コルムキル(聖コルンバ)頌歌」が最もよく知られている.同じくウェールズ語についても現存する最古の文書は13世紀以降だが,「アネイリン」「タリエシン」などの詩歌の起源は6世紀にさかのぼるらしい.周縁部において俗語書記文化の発達がこれほど早かったのはなぜだろうか.原 (213) が次のように解説している.

この答えはまさにその文化的周縁性にあるといっていいだろう.フランスの社会言語学者バッジオーニの提唱していることだが,ローマ帝国の周縁部(リメース)とその隣接地帯,すなわちブリタニア諸島,ドイツ北東部,スカンジナビア,ボヘミアなどでは,ラテン語は教養人にとっても外国語でしかなく,その使われ方も古風なままであった.権威ある言語が自由に日常的に用いられないというなかで,地元のことばをそれに代用するという考え方が生まれ,ラテン語に似せた書きことばでの使用がはじまったというわけである.

したがって,ヨーロッパでは,ローマ帝国の周縁部,その内外で最初に,日常的に用いられる俗語による書きことばが誕生した.こうした俗語が現代の国語・民族語のはっきりとした外部であるヒベルニアでは,六世紀には詩歌ばかりでなく,年代記や法的文書までゲール語で書かれるようになった.カムリー語の法的文書は一〇世紀,聖人伝はラテン語からの翻訳で一一世紀末になって登場するので,ゲール語と比べるとその使用度は低い.ワリアが一部はローマ帝国領内だったということも関係しているだろう.

周縁部ではラテン語の権威が適度に弱かったという点が重要である.ラテン語と距離を置く姿勢が俗語の使用を促したのである.別の観点からみれば,周縁部の社会は,ラテン語から刺激こそ受けたが,ラテン語をそのまま使用するほどにはラテン語かぶれしなかったし,母語との言語差もあって語学上のハンディを感じていたということではないか.

そして,そのような語学上の困難を少しでも楽に乗り越えるために,学習の種々のテクニックがよく発達したのも周縁部の特徴である.「#1903. 分かち書きの歴史」 ([2014-07-13-1]) の記事で,分かち書きは「外国語学習者がその言語の読み書きを容易にするために編み出した語学学習のテクニックに由来する」と述べたが,この書記上の革新をもたらしたのは,ほかならぬイギリス諸島という周縁に住む修道僧たちだったのである.

・ 原 聖 『ケルトの水脈』 講談社,2007年.

2019-07-28 Sun

■ #3744. German の指示対象の歴史的変化と語源 [german][germanic][etymology][ethnic_group]

昨日の記事「#3743. Celt の指示対象の歴史的変化」 ([2019-07-27-1]) に続き,今回は German という語の指示対象の変遷について.

古代ローマ人は,中欧から北欧にかけて居住していたゲルマン系諸語を話す民族を Germānī (ゲルマニア人)と呼んでいた.そして,その対応する地域名が,現代の Germany (ドイツ)に連なる Germānia (ゲルマニア)だった.基本的には他称であり,自称として用いられたことはないようだ.

英語でも後期中英語期に German がゲルマニア人を指す語としてフランス語を介して入ってきたが,近代の16世紀に入ると現代風にドイツ人を指すようになった.それ以前には,英語でドイツ人を指す名称としては Almain や Dutch が一般的だった.

German の語源については諸説ある.1つは,ゴール人が東方のゲルマニア人をケルト語で「隣人」と呼んだのではないかという説だ(cf. 古アイルランド語の gair (隣人)).もう1つは,同じくケルト語 gairm (叫び)に由来するという説もある.つまり「騒々しい民」ほどの蔑称だ.また,ゲルマン語で「貪欲な民」を意味する *Geramanniz (cf. OHG ger "greedy" + MAN) がラテン語へ借用されたものとする説もある.

しかし,いずれの語源説も音韻上その他の難点があり,未詳といってよいだろう.

2019-06-25 Tue

■ #3711. 印欧祖語とゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる基本英単語のサンプル [indo-european][germanic][lexicology][etymology]

『英語語源辞典』によると,印欧語比較言語学の成果により,1,000から2,000ほどの印欧語根が想定されている.そのおよそ半数が現代英語の語彙にも反映されているといわれるが,主に基本語彙として受け継がれているものを列挙しよう(寺澤,p. 1656;カッコは借用語を表わす).

| 身体 | arm, brow, ear, eye, foot, heart, knee, lip, nail, navel, tooth |

| 家族 | father, mother, brother, sister, son, daughter, nephew, widow |

| ?????? | beaver, cow, ewe, goat, goose, hare, hart, hound, mouse, sow, wolf; bee, wasp; louse, nit; crane, ern(e), raven, starling; fish, (lax) |

| 罎???? | alder, ash, asp(en), beech, birch, fir, hazel, tree, withy |

| 飲食物 | bean, mead, salt, water, (wine) |

| 天体・自然現象 | moon, star, sun; snow |

| 数詞 | one, two, ..., ten, hundred |

| 代名詞 | I, me, thou, ye, it, that, who, what |

| 動詞 | be, bear, come, do, eat, know, lie, murmur, ride, seek, sew, sing, stand, weave |

| 形容詞 | full, light, middle, naked, new, sweet, young |

| その他 | acre, ax(e), furrow, month, name, night, summer, wheel, word, work, year, yoke |

一方,ゲルマン祖語にさかのぼる,ゲルマン語に特有の基本英単語を挙げてみよう(寺澤,p. 1657).眺めてみると,印欧祖語の時代に比べ「社会生活の進歩,環境の変化がうかがわれ」「とくに,農耕・牧畜関係の語の充実とともに,航海・漁業関係の語が豊富であり,戦争・宗教関係の語も目立つ」(寺澤,p. 1657)ことが確認できる.

| 身体 | bone, hand, toe |

| 穀物・食物 | berry, broth, knead, loaf, wheat |

| 動物 | bear, lamb, sheep, †hengest (G Hangst), roe, seal, weasel |

| 鳥類 | dove, hawk, hen, rave, stork |

| 海洋 | cliff, east, west, north, south, ebb, sail, sea, ship, steer, keel, haven, sound, strand, swim, net, tackle, stem |

| 戦争 | bow, helm, shield, sword, weapon |

| 絎???? | god, ghost, heaven, hell, holy, soul, weird, werewolf |

| 住居 | bed, bench, hall |

| 社会 | atheling, earl, king, knight, lord, lady, knave, wife, borough |

| 経済 | buy, ware, worth |

| その他 | winter, rain, ground steel, tin |

「基本語彙」を巡る議論については,(基本語彙) の各記事を参照.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow