2014-10-02 Thu

■ #1984. 会話的含意と意味変化 [semantic_change][pragmatics][implicature][polysemy][cooperative_principle][metonymy][metaphor]

「#1976. 会話的含意とその他の様々な含意」 ([2014-09-24-1]) で,異なる種類の含意 (implicature) を整理した.このなかでも特に相互の区別が問題となるのは,Grice の particularized conversational implicature, generalized conversational implicature, conventional implicature の3種である.これらの含意は,この順序で形態との結びつきが強くなり,慣習化あるいはコード化の度合いが高くなる.

ところで,これらの語用論的な含意と意味変化や多義化とは密接に結びついている.意味変化や多義化は,ある形態(ここでは語を例にとる)と結びつけられている既存の語義に,新しい語義が付け加わったり,古い語義が消失していく過程である.意味変化を構成する基本的な過程には2つある (Kearns 123) .

(1) Fa > Fab: Form F with sense a acquires an additional sense b

(2) Fab > Fb: Form F with senses a and b loses sense a

(1) はある形態 F に結びつけられた語義 a に,新語義 b が加えられる過程,(2) はある形態 F に結びつけられた語義 a と b から語義 a が失われる過程だ.(1) と (2) が継起すれば,結果として Fa から Fb へと語義が推移したことになる.特に重要なのは,新らしい語義が加わる (1) の過程である.いかにして,F と関連づけられた a の上に b が加わるのだろうか.

ここで上記の種々の含意に参加してもらおう.particularized conversational implicature では,文字通りの意味 a をもとに,推論・計算によって含意,すなわち a とは異なる意味 b が導き出される.しかし,それは会話における単発の含意にすぎず,形態との結びつきは弱いため,定式化すれば F を伴わない「a > ab」という過程だろう.一方,conventional implicature は,形態と強く結びついた含意,もっといえば語にコード化された意味であるから,意味変化の観点からは,変化が完了した後の安定した状態,ここでは Fab という状態に対応する.では,この2つの間を取り持ち,意味変化の動的な過程,すなわち (1) で定式化された「Fa > Fab」の過程に対応するものは何だろうか.それは generalized conversational implicature である.generalized conversational implicature は,意味変化の過程の第1段階に関わる重要な種類の含意ということになる.

会話的含意と意味変化の接点はほかにもある.例えば,意味変化の典型的なパターンである一般化 (generalisation) と特殊化 (specialisation) (cf. 「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1])) は,協調の原則 (cooperative principle) に基づく含意という観点から論じることができる.Grice を受けて協調の原則を発展させた新 Grice 派 (neo-Gricean) の Horn は,一般化は例外なく,そして特殊化も主として R[elation]-principle ("Make your contribution necessary.") によって説明されるという (Kearns 129--31) .

Kearns は,implicature と metonymy や metaphor との関係についても論じている.そして,意味変化における implicature の役割の普遍性について,次のように締めくくっている.

. . . if implicature is construed broadly to subsume all the inferential processes available in language use, then most, perhaps all of the major types of semantic change can be attributed to implicature. Differentiating more finely, metaphor and metonymy (which are themselves not always readily distinguishable) produce the ambiguity or polysemy pattern of added meaning, in contrast to the merger pattern, which is commonly attributed to information-strengthening generalized conversational implicature . . . . On an alternative view, implicature (narrowly construed) and metonymy are grouped together in contrast to metaphor, on the grounds that the two former mechanisms are based on sense contiguity, while metaphor is based on sense comparison or analogy. (139)

・ Kearns, Kate. "Implicature and Language Change" Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 123--40.

2014-09-29 Mon

■ #1981. 間主観化 [subjectification][intersubjectification][semantic_change][unidirectionality][face][t/v_distinction][terminology][discourse_marker][onomasiology]

今日は,昨日の記事「#1980. 主観化」 ([2014-09-28-1]) を発展させた話題として間主観化 (intersubjectification) について取り上げる.Traugott は,"nonsubjective > subjective" という意味変化の延長線上に "subjective > intersubjective" というもう1つの段階があり得ることを提案している.まず,間主観化 (intersubjectification) の行き着く先である間主観性 (intersubjectivity) について,Traugott (128) の説明をみてみよう.

[I]ntersubjectivity is the explicit expression of the SP/W's attention to the 'self' of addressee/reader in both an epistemic sense (paying attention to their presumed attitudes to the content of what is said), and in a more social sense (paying attention to their 'face' or 'image needs' associated with social stance and identity). (128)

そして,間主観化 (intersubjectification) とは,"the development of meanings that encode speaker/writers' attention to the cognitive stances and social identities of addressees" (124) と説明される.

英語から間主観的な表現の例を挙げよう.Actually, I will drive you to the dentist. の "Actually" が間主観的な役割を果たしているという.この "Actually" は,「あなたはこの提案を断るかもしれないことを承知であえて言いますが」ほどの意味を含んでおり,聞き手の face に対してある種の配慮を表わす話し手の態度を表わしている.また,かつての英語における2人称代名詞 you と thou の使い分け (cf. t/v_distinction) も,典型的な間主観的表現である.

間主観化を示す例を挙げると,Let's take our pills now, Roger. における let's がある.本来 let's は,let us (allow us) という命令文からの発達であり,let's へ短縮しながら "I propose" ほどの奨励・勧告の意を表わすようになった.これが,さらに親が子になだめるように動作を促す "care-giver register" での用法へと発展したのである.奨励・勧告の発達は主観化とみてよいだろうが,その次の発展段階は,話し手(親)の聞き手(子)への「なだめて促す」思いやりの態度をコード化しているという点で間主観化ととらえることができる.命令文に先行する please や pray などの用法の発達も,同様に間主観化の例とみることができる.さらに,「まあ,そういうことであれば同意します」ほどを意味する談話標識 well の発達ももう1つの例とみてよい.

聞き手の face を重んじる話し手の態度を埋め込むのが間主観性あるいは間主観化だとすれば,英語というよりはむしろ日本語の出番だろう.実際,間主観性や間主観化の研究では,日本語は引っ張りだこである.各種の敬譲表現に始まり,終助詞,談話標識としての「さて」など,多くの表現に間主観性がみられる.Traugott の "nonsubjective > subjective > intersubjective" という変化の方向性を仮定するのであれば,日本語は,そのどん詰まりにまで行き切った表現が数多く存在する,比較的珍しい言語ということになる.では,どん詰まりにまで行き切った表現のその後はどうなるのか.次の発展段階がないということになれば,どん詰まりには次々と表現が蓄積されることになりそうだが,一方で廃用となっていく表現も多いだろう.Traugott (136) は,次のように想像している.

. . . by hypothesis, intersubjectification is a semasiological end-point for a particular form-meaning pair; onomasiologically, however, an intersubjective category will over time come to have more or fewer members, depending on cultural preference, register, etc.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "From Subjectification to Intersubjectification." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 124--39.

2014-09-28 Sun

■ #1980. 主観化 [subjectification][grammaticalisation][semantic_change][unidirectionality][adjective][intensifier][terminology][discourse_marker]

語用論 (pragmatics) や文法化 (grammaticalisation) や意味変化 (semantic_change) の研究では,主観化 (subjectification) ということがしばしば話題にされる.一言でいえば,「指示的,命題的意味からテキスト的,感情表出的,あるいは,対人的 (interpersonal) への意味変化」(秋元,p. 11)である.命題の意味が話者の主観的態度に重きをおく意味へと変化する過程であり,文法化において典型的にみられる方向性であるといわれる.図式的にいえば,"propositional > textual > expressive/interpersonal" という方向だ.

秋元 (11--13) に従って英語史からの例を挙げると,運動から未来の意志・推論を表わす be going to の発達,法助動詞 must, may などの義務的用法 (deontic) から認識的用法 (epistemic) への発達,談話標識の発達,強調副詞の発達などがある.より具体的に,動詞 promise の経た主観化をみてみよう.中英語にフランス語から借用された 動詞 promise は,本来は有生の主語をとり,約束という発話内行為を行うことを意味した.16世紀には名詞目的語を従えて「予告する,予言する」の意味を獲得し,無声の主語をも許容するようになる.18世紀には,非定形補文をとって統語的繰り上げの用法を発達させ,非意志的・認識的な意味を獲得するに至る.結果,The conflict may promise to escalate into war. のような文が可能になった.動詞 promise が経てきた主観化のプロセスは,"full thematic predicates > raising predicates > quasi-modals > modal operator" と図式化できるだろう.

もう1つ,形容詞 lovely の主観化についても触れておこう.本来この形容詞は人間の属性を意味したが,18世紀頃から身体の特性を表わすようになり,次いで価値を表わすようになった.19世紀中頃からは強意語 (intensifier) としても用いられるようになり,ついにはさらに「素晴らしい!」ほどを意味する反応詞 (response particle) としての用法も発達させた.過程を図式化すれば "descriptive adjective > affective adjective > intensifier/pragmatic particle" といったところか.関連して,形容詞が評価的な意味を獲得する事例については「#1099. 記述の形容詞と評価の形容詞」 ([2012-04-30-1]),「#1100. Farsi の形容詞区分の通時的な意味合い」 ([2012-05-01-1]),「#1400. relational adjective から qualitative adjective への意味変化の原動力」 ([2013-02-25-1]) で取り上げたので,参照されたい.強意語の発達については,「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1]),「#1220. 初期近代英語における強意副詞の拡大」 ([2012-08-29-1]) を参照.

ほかにも,Traugott (126--27) によれば,after all, in fact, however などの談話標識としての発達,even の尺度詞としての発達,only の焦点詞としての発達などが挙げられるし,日本語からの例として,文頭の「でも」の談話標識としての発達や,文末の「わけ」の主観的な態度を含んだ理由説明の用法の発達なども指摘される.

この種の意味変化の方向性という話題になると,必ず反例らしきものが指摘される.実際に,反主観化 (de-subjectification) と目される例もある.例えば,criminal law の criminal は客観的で記述的な意味をもっているが,歴史的にはこの形容詞では a criminal tyrant におけるような主観的で評価的な意味が先行していたという.また,英語では歴史的に受動態が発達してきたが,受動態は典型的に動作主を明示しない点で反主観的な表現といえる.

・ 秋元 実治 『増補 文法化とイディオム化』 ひつじ書房,2014年.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "From Subjectification to Intersubjectification." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 124--39.

2014-09-21 Sun

■ #1973. Meillet の意味変化の3つの原因 [semantic_change][semantics][register]

昨日の記事「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1]) で引用した Meillet は,文法化のみならず語の意味変化についても重要な考察を加えている.「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]) で部分的に触れたように,特に意味変化の原因について,まとまった記述を残している.

Meillet によれば,意味変化の一般的原因には,言語的原因,歴史的原因,社会的原因の3種が区別される.これらは互いにほとんど関連するところがないため,明確に区別すべきだと論じている.まずは,適用範囲の狭いといわれる言語的原因から.

Quelques changements, en nombre assez restreint du reste, procèdent de conditions proprement linguistiques : ils proviennent de la structure de certaines phrases, où tel mot paraît jouer un rôle spécial. (239)

ここに属するのは,いわゆる文法化の事例などである.フランス語の homme, chose, pas, rien, personne などにおいて,具体的な意味が抽象的・文法的な意味へと変化した例が挙げられている.2つめは,歴史的原因である.

Un second type de changements de sens est celui où les choses exprimées par les mots viennent à changer. (241)

これは指示対象あるいはモノの歴史的変化に依存する語の意味変化である.「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) でいえば,最初に挙げられている代用 (substitution) に相当する.フランス語の plume (ペン)は,かつては鉄筆を指示したが,後に鵞ペンを指示するようになったという例が挙げられている.名前は変わらないが,技術の発展などによりそれが指すモノが変わった場合に典型的にみられる意味変化である.3つめは社会的原因である.

... la répartition des hommes de même langue en groupes distincts: c'est de cette hétérogénéité des hommes de même langue que procèdent le plus grand nombre des changements de sens, et sans doute tous ceux qui ne s'expliquent pas par les causes précitées. (243--44)

Meillet はこの社会的な原因を最も重要な要因であると考えており,紙幅を割いて論じている.1つの言語の異なる変種においては,それぞれの話者集団に特有の register に彩られた言語使用が発達する.一般的な変種においてある意味をもって用いられている語が,特殊化した変種において別の意味をもって用いられることは,ごく普通に見られる.犯罪者集団の隠語,職業集団の俗語,専門集団の術語などである.各変種で発生した新しい語義が変種間の境を越えて往来すれば,結果としてその語の意味は変化(あるいは多義化)したことになる.

意味変化の3種類の原因と多くの例を挙げたうえで,Meillet は次のように締めくくっている.

Ces exemples, où l'on a remarqué seulement les plus gros faits et les plus généraux, permettent de se faire une idée de la manière dont les faits linguistiques, les faits historiques et les faits sociaux s'unissent, agissent et réagissent pour transformer le sens des mots; on voit que, partout, le moment essentiel est le passage d'un mot de la langue générale à une langue particulière, ou le fait inverse, ou tous les deux, et que, par suite, les changements de sens doivent être considérés comme ayant pour condition principale la différenciation des éléments qui constituent les sociétés. (271)

この碩学のすぐれて社会言語学的な立場が表明されている結論といえるだろう.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). Rpt. in Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1958. 230--71.

2014-09-12 Fri

■ #1964. プロトタイプ [prototype][phonology][phoneme][phonetics][syllable][prosody][terminology][semantic_change][family_resemblance][philosophy_of_language][onomasiology]

認知言語学では,プロトタイプ (prototype) の考え方が重視される.アリストテレス的なデジタルなカテゴリー観に疑問を呈した Wittgenstein (1889--1951) が,ファジーでアナログな家族的類似 (family resemblance) に基づいたカテゴリー観を示したのを1つの源流として,プロトタイプは認知言語学において重要なキーワードとして発展してきた.プロトタイプ理論によると,カテゴリーは素性 (feature) の有無の組み合わせによって表現されるものではなく,特性 (attribute) の程度の組み合わせによって表現されるものである.程度問題であるから,そのカテゴリーの中心に位置づけられるような最もふさわしい典型的な成員もあれば,周辺に位置づけられるあまり典型的でない成員もあると考える.例えば,「鳥」というカテゴリーにおいて,スズメやツバメは中心的(プロトタイプ的)な成員とみなせるが,ペンギンやダチョウは周辺的(非プロトタイプ的)な成員である.コウモリは科学的知識により哺乳動物と知られており,古典的なカテゴリー観によれば「鳥」ではないとされるが,プロトタイプ理論のカテゴリー観によれば,限りなく周辺的な「鳥」であるとみなすこともできる.このように,「○○らしさ」の程度が100%から0%までの連続体をなしており,どこからが○○であり,どこからが○○でないかの明確な線引きはできないとみる.

考えてみれば,人間は日常的に事物をプロトタイプの観点からみている.赤でもなく黄色でもない色を目にしてどちらかと悩むのは,プロトタイプ的な赤と黄色を知っており,いずれからも遠い周辺的な色だからだ.逆に,赤いモノを挙げなさいと言われれば,日本語母語話者であれば,典型的に郵便ポスト,リンゴ,トマト,血などの答えが返される.同様に,「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) で話題にした FURNITURE, FRUIT, VEHICLE, WEAPON, VEGETABLE, TOOL, BIRD, SPORT, TOY, CLOTHING それぞれの典型的な成員を挙げなさいといわれると,多くの英語話者の答えがおよそ一致する.

英語の FURNITURE での実験例をみてみよう.E. Rosch は,約200人のアメリカ人学生に,60個の家具の名前を与え,それぞれがどのくらい「家具らしい」かを1から7までの7段階評価(1が最も家具らしい)で示させた.それを集計すると,家具の典型性の感覚が驚くほど共有されていることが明らかになった.Rosch ("Cognitive Representations of Semantic Categories." Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 104 (1975): 192--233. p. 229) の調査報告を要約した Taylor (46) の表を再現しよう.

| Member | Rank | Specific score |

|---|---|---|

| chair | 1.5 | 1.04 |

| sofa | 1.5 | 1.04 |

| couch | 3.5 | 1.10 |

| table | 3.5 | 1.10 |

| easy chair | 5 | 1.33 |

| dresser | 6.5 | 1.37 |

| rocking chair | 6.5 | 1.37 |

| coffee table | 8 | 1.38 |

| rocker | 9 | 1.42 |

| love seat | 10 | 1.44 |

| chest of drawers | 11 | 1.48 |

| desk | 12 | 1.54 |

| bed | 13 | 1.58 |

| bureau | 14 | 1.59 |

| davenport | 15.5 | 1.61 |

| end table | 15.5 | 1.61 |

| divan | 17 | 1.70 |

| night table | 18 | 1.83 |

| chest | 19 | 1.98 |

| cedar chest | 20 | 2.11 |

| vanity | 21 | 2.13 |

| bookcase | 22 | 2.15 |

| lounge | 23 | 2.17 |

| chaise longue | 24 | 2.26 |

| ottoman | 25 | 2.43 |

| footstool | 26 | 2.45 |

| cabinet | 27 | 2.49 |

| china closet | 28 | 2.59 |

| bench | 29 | 2.77 |

| buffet | 30 | 2.89 |

| lamp | 31 | 2.94 |

| stool | 32 | 3.13 |

| hassock | 33 | 3.43 |

| drawers | 34 | 3.63 |

| piano | 35 | 3.64 |

| cushion | 36 | 3.70 |

| magazine rack | 37 | 4.14 |

| hi-fi | 38 | 4.25 |

| cupboard | 39 | 4.27 |

| stereo | 40 | 4.32 |

| mirror | 41 | 4.39 |

| television | 42 | 4.41 |

| bar | 43 | 4.46 |

| shelf | 44 | 4.52 |

| rug | 45 | 5.00 |

| pillow | 46 | 5.03 |

| wastebasket | 47 | 5.34 |

| radio | 48 | 5.37 |

| sewing machine | 49 | 5.39 |

| stove | 50 | 5.40 |

| counter | 51 | 5.44 |

| clock | 52 | 5.48 |

| drapes | 53 | 5.67 |

| refrigerator | 54 | 5.70 |

| picture | 55 | 5.75 |

| closet | 56 | 5.95 |

| vase | 57 | 6.23 |

| ashtray | 58 | 6.35 |

| fan | 59 | 6.49 |

| telephone | 60 | 6.68 |

プロトタイプ理論は,言語変化の記述や説明にも効果を発揮する.例えば,ある種の語の意味変化は,かつて周辺的だった語義が今や中心的な語義として用いられるようになったものとして説明できる.この場合,語の意味のプロトタイプがAからBへ移ったと表現できるだろう.構文や音韻など他部門の変化についても同様にプロトタイプの観点から迫ることができる.

また,プロトタイプは「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) と補完的な関係にあることも指摘しておこう.プロトタイプは,ある語が与えられたとき,対応する典型的な意味や指示対象を思い浮かべることのできる能力や作用に関係する.一方,基本レベル範疇は,ある意味や指示対象が与えられたとき,対応する典型的な語を思い浮かべることのできる能力や作用に関係する.前者は semasiological,後者は onomasiological な視点である.

・ Taylor, John R. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

2014-09-03 Wed

■ #1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性 [semantic_change][semantics][synaesthesia][rhetoric][grammaticalisation][prediction_of_language_change][speed_of_change][function_of_language][subjectification]

語の意味変化が予測不可能であることは,他の言語変化と同様である.すでに起こった意味変化を研究することは重要だが,そこからわかることは意味変化の一般的な傾向であり,将来の意味変化を予測させるほどの決定力はない.「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]) で「法則」の名に値するかもしれない意味変化の例を見たが,もしそれが真実だとしても例外中の例外といえるだろう.ほとんどは,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]),「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]),「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で示唆されるような意味変化の一般的な傾向である.

Brinton and Arnovick (87) は,次のような傾向を指摘している.

・ 素早く起こる.そのために辞書への登録が追いつかないこともある.ex. desultory (slow, aimlessly, despondently), peruse (to skim or read casually)

・ 具体的な意味から抽象的な意味へ.ex. understand

・ 中立的な意味から非中立的な意味へ.ex. esteem (cf. 「#1099. 記述の形容詞と評価の形容詞」 ([2012-04-30-1]),「#1100. Farsi の形容詞区分の通時的な意味合い」 ([2012-05-01-1]),「#1400. relational adjective から qualitative adjective への意味変化の原動力」 ([2013-02-25-1]))

・ 強い感情的な意味が弱まる傾向.ex. awful

・ 侮辱的な語は動物や下級の人々を表わす表現から.ex. rat, villain

・ 比喩的な表現は日常的な経験に基づく.ex. mouth of a river

・ 文法化 (grammaticalisation) の一方向性

・ 不規則変化は,言語外的な要因にさらされやすい名詞にとりわけ顕著である

もう1つ,意味変化の一般的な傾向というよりは,それ自体の特質と呼ぶべきだが,言語において意味変化が何らかの形でとかく頻繁に生じるということは明言してよい事実だろう.上で参照した Brinton and Arnovick も,"Of all the components of language, lexical meaning is most susceptible to change. Semantics is not rule-governed in the same way that grammar is because the connection between sound and meaning is arbitrary and conventional." (76) と述べている.また,意味変化の日常性について,前田 (106) は以下のように述べている.

とかく口語・俗語では意味の変化が活発である.これに比べると,文法の変化はかなりまれで,おそらく一生のうちでそれと気づくものはわずかだろう.音の変化は,日本語の「ら抜きことば」のように,もう少し気づかれやすいが,それでも意味変化の豊富さに比べれば目立たない.では,なぜ意味変化 (semantic change) はこれほど頻繁に起こるのだろうか.その答えは,おそらく意味変化がディスコース (discourse) における日常的営みから直接生ずるものだからである.

最後の文を言い換えて,前田 (130) は「意味の伝達が日常の言語活動の舞台であるディスコースにおけるコミュニケーション活動の目的と直接結びついているからである」と結論している.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

2014-09-02 Tue

■ #1954. 意味変化によって意味不明となった英文 [semantic_change]

Brinton and Arnovick (87) に,語の意味変化の例を示すおもしろい英文が載っていた.語形は変わっていないが,語の意味が変化してしまったことにより,一見普通の英文に見えるものの実際に読むと意味不明,あるいは矛盾を来たすという文章だ.

He was a happy and sad girl who lived in a town forty miles from the closest neighbor. His unmarried sister, a wife who was a vegetarian teetotaler, ate meat and drank liquor three times a day. She was so fond of oatmeal bread made from the corn her brother grew that she starved from overeating. He fed nuts to the deer that lived in the branches of an apple tree which bore pears. A silly and wise boor everyone liked, he was a lewd man whom the general censure held to be a model of chastity. (adapted from John Algeo and Carmen Acevedo Butcher. 2005. Problems in the Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th edn. Boston: Thomson-Wadsworth, pp. 224--5.)

赤字で示した語が意味変化を経た語である.現行の語義ではなく,今は失われたかつての語義を前提とすると,この文章はすっと意味が通るようになる.以下,各語について,古い語義と経験した意味変化のタイプをまとめる(cf. 「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1])).

| Word | Old meaning | Type of semantic change | See also: |

|---|---|---|---|

| sad | sober | metonymy | |

| girl | youth | specialisation | |

| town | small enclosure | cultural change | 「#1395. up and down」 ([2013-02-20-1]) |

| wife | woman | specialisation | 「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]) |

| meat | food | specialisation | 「#780. ベジタリアンの meat」 ([2011-06-16-1]) |

| liquor | liquid | specialisation | |

| corn | grain | specialisation | |

| starve | die | specialisation, weakening | 「#596. die の謎」 ([2010-12-14-1]) |

| deer | animal | specialisation | 「#127. deer, beast, and animal」 ([2009-09-01-1]) 「#128. deer の「動物」の意味はいつまで残っていたか」 ([2009-09-02-1]) |

| apple | fruit | specialisation | |

| silly | blessed | pejoration | 「#505. silly の意味変化」 ([2010-09-14-1]) |

| boor | farmer | pejoration | |

| lewd | lay | pejoration | |

| censure | opinion | pejoration, metonymy |

Shakespeare などとりわけ初期近代英語で書かれた英文を読むときに,上のような体験が頻発する.見た目は現代英語風なのだが,ここ数世紀の間で生じた意味変化により,一見理解できそうで理解できない文章が多い.この落とし穴には,母語話者もしばしば陥る.実際,現代日本語母語話者が日本語の古文を読むときにも経験することなので,想像しやすいだろう.

私のお気に入りの英語史からの例は,ちょっとできすぎているのだが,「#742. amusing, awful, and artificial」 ([2011-05-09-1]) である.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

2014-09-01 Mon

■ #1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2) [semantic_change][semantics][history_of_linguistics]

「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) と同じものだが,Stern の著書の解題を執筆した山中 (10) に,意味変化の7分類がずっとわかりやすくまとめられていた.

A 紊????荀????

i 代用 (substitution)

(a) 指示対象の物的変化: house, ship, telephone

(b) 指示対象に関する知識の変化: atom, electricity

(c) 指示対象に対する態度の変化: scholasticism, Home Rule

B 言語的要因

I 表現関係の推移

ii 蕁??ィ (analogy)

(a) 結合上の類推: reversion [reversal とすべきところに]

(b) 相関的類推: red letter day → black letter day

(c) 音韻的類推: bless ? bliss, start naked ? stark naked

iii 縮約 (shortening)

(a) 短縮: pop < popular concert, props < properties

(b) ??????: fall (of the leaf), (sewing) machine

II 指示関係の推移

iv 命名 (nomination)

(a) 命名: Kodak, Tono-Bungay ─┐

(b) 転移: labyrinth [of the ear], crane ├ 意図的

(c) 隠喩: the herring-pond (= the Atlantic) ─┘

v 荵∝Щ (transfer)

(a) 類似性に基づくもの: pyramid, saddle ('鞍部') ─┐

(b) その他の関係に基づくもの: pigtails (= China men) │

III 主観的関係の推移 │

vi 代換 (permutation) ├ 非意図的

(a) 材料から産物へ: copper, nickel │

(b) 容器から内容へ: tub, wardrobe │

(c) 部分から全体へ: bureau, dungeon etc. │

vii 適用 (adequation): horn ('角' → '角製の笛' → 'ホルン') ─┘

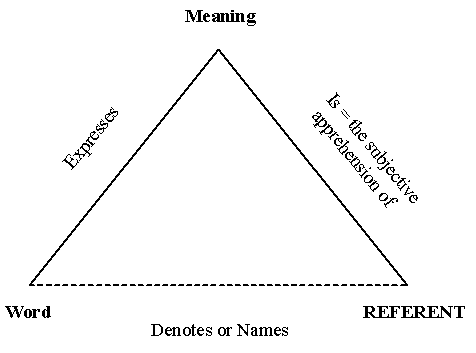

補足までに,Stern の意味論は基本的に Ogden and Richards の意味の三角形 (semiotic triangle; cf. 「#1769. Ogden and Richards の semiotic triangle」 ([2014-03-01-1])) に基づいたものだが,用語を少し改変して次のようにしている(山中,p. 10).

さて,山中 (10) は解題のなかで Stern の通時的意味論をむしろ共時的意味論に多大な貢献をしたものとして評価している.

iv (b)--(c) と,Stern 自身が揺れ (fluctuation) という総称を与えた v--vii は意図的/非意図的という基準一つによって区別され,現象的には同種・同範囲である.別の角度からいえば,彼が「本来の意味変化」とみている「揺れ」は,伝達の場面場面で起こる共時的な転義と本質的に変わりがないということになる.通時的意味論は当初から修辞学への傾斜をみせていたが,Stern の徹底した心理学主義によってその深い理由が明らかになったとみることができる.すべての言語変化は日常の言語活動に根ざしている,別のことばでいえば共時的原理によって説明可能であるという Paul (1880) のことばを,通時的意味論はこの段階ではっきり追認したことになる.

これは,Stern にとっても通時的意味論にとっても皮肉なことに,通時的意味論は共時的な意味の原理に包摂され,それに吸い込まれるようにして自らの意義を消滅させていったという評だ.さらに Stern にとって皮肉なことに,意味の原理を論じている著書の前半部分には,共時的意味論において考慮すべき数々の二項対立が列挙されており,その重要性が今でも色あせていないことだ.そこでは,知的意味/主情的意味,語義/実際的意味,内在的意味/偶有的意味,意味/適用範囲,基本的意味/関係的意味,イメージ/思考,自義/共義などの区別が論じられている.

しかし,Stern に通時的ではなく共時的な貢献を認めて終えるという評価は,やや酷かもしれない.というのは,「#1686. 言語学的意味論の略史」 ([2013-12-08-1]) でみたように,共時的な意味論ですら言語学において独自の領域をもっているかどうかと問われれば,答えは怪しいからだ.意味にせよ意味の変化にせよ,学際的なアプローチで研究されるのが普通になってきた.つまり,言語そのものが学際的なアプローチなしでは研究できなくなってきている.いずれにしても,意味論史における Stern の古典としての価値は否定できない.

・ 山中 桂一,原口 庄輔,今西 典子 (編) 『意味論』 研究社英語学文献解題 第7巻.研究社.2005年.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-08-25 Mon

■ #1946. 機能的な観点からみる短化 [shortening][clipping][word_formation][morphology][function_of_language][style][semantics][semantic_change][euphemism][language_change][slang]

shortening (短化)という過程は,言語において重要かつ頻繁にみられる語形成法の1つである.英語史でみても,とりわけ現代英語で shortening が盛んになってきていることは,「#875. Bauer による現代英語の新語のソースのまとめ」 ([2011-09-19-1]) で確認した.関連して,「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]),「#894. shortening の分類 (2)」 ([2011-10-08-1]) では短化にも様々な種類があることを確認し,「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]),「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]),「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1]) では情報伝達の効率という観点から短化を考察した.

上記のように,短化は主として形態論の話題として,あるいは情報理論との関連で語られるのが普通だが,Stern は機能的・意味的な観点から短化の過程に注目している.Stern は,「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) で示したように,短化を意味変化の分類のなかに含めている.すべての短化が意味の変化を伴うわけではないかもしれないが,例えば private soldier (兵卒)が private と短化したとき,既存の語(形容詞)である private は新たな(名詞の)語義を獲得したことになり,その観点からみれば意味変化が生じたことになる.

しかし,private soldier のように,短化した結果の語形が既存の語と同一となるために意味変化が生じるというケースとは別に,rhinoceros → rhino, advertisement → ad などの clipping (切株)の例のように,結果の語形が新語彙項目となるケースがある.ここでは先の意味での「意味変化」はなく意味論的に語るべきものはないようにも思われるが,rhinoceros と rhino の意味の差,advertisement と ad の意味の差がもしあるとすれば,これらの短化は意味論的な含意をもつ話題ということになる.

Stern (256) は,短化を形態的な過程であるとともに,機能的な観点から重要な過程であるとみている.実際,短化の原因のなかで最重要のものは,機能的な要因であるとまで述べている.Stern (256) の主張を引用する.

Starting with the communicative and symbolic functions, I have already pointed out above . . . that brevity may conduce to a better understanding, and too many words confuse the point at issue; the picking out of a few salient items may give a better idea of the topic than prolonged wallowing in details; the hearer may understand the shortened expression quicker and better.

The expressive function is partly covered by signals, but a shortened expression by itself may, owing to its unusual and perhaps ungrammatical, form, reflect better the speaker's emotional state and make the hearer aware of it. Clippings are very often intended to make the words express sympathy or endearment towards the persons addressed; nursery speech abounds in nighties, tootsies, etc., and clippings of proper names, transforming them into pet names, are often due to a similar desire for emotive effects . . . . The numerous shortenings (clippings) in slang and cant often aim at a humourous effect.

Conciseness and brevity increase vivacity, and thus also the effectiveness of speech; brevity is the soul of wit; the purposive function may consequently be better served by shortened phrases.

形態論や情報理論のいわば機械的な観点から短化をみるにとどまらず,言語使用の目的,表現力,文体といった機能的な側面から短化をとらえる洞察は,Stern の面目躍如たるところである.形態を短化することでむしろ新機能が付加される逆説が興味深い.

引用の文章で言及されている婉曲表現 nighties と関連して,「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) 及び「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-08-02 Sat

■ #1923. only の意味の but [adverb][shortening][negative][negative_cycle][semantic_change][reanalysis][metanalysis][terminology][clipping][but]

現代英語で but は多義語の1つである.用法が非常に多く,品詞だけみても接続詞,前置詞,代名詞,副詞,名詞,動詞までと範囲が広い.このなかで副詞としての用法に注目したい.文語において only の意味で用いられる but がある.例文を挙げよう.

・ He is but a child.

・ There is but one answer to your question.

・ There were a lot of famous people there: Tom Hanks and Julia Roberts, to name but two.

・ I heard it but now.

・ I don't think we'll manage it. Still, we can but try.

but のこの意味・用法は歴史的にはどこから来たのだろうか.考えてみれば,He is but a child. という文は He is nothing but a child. とも言い換えられる.後者では but は「?を除いて」の意の前置詞と分析され全体としては否定構造となるが,前者の肯定構造と事実上同義となるのは一見すると不思議である.しかし,歴史的には only の意味の but は,まさに nothing but のような否定構造から否定辞が脱落することによって生じたのである.短縮あるいは省略の事例である.Stern (264) は次のように述べている.

In English, an original ne--butan has been shortened to but: we nabbað her buton fif hlafas and twegen fiscas > we have here but five loafs and two fishes (Horn, Sprachkörper 90), he nis but a child > he is but a child (NED but 6). The immediate cause of the omission of the negation is not quite certain. It is not impossible that influence from other uses of but may have intervened.

OED の but, prep., adv., conj., n.3, adj., and pron. の語義6aにも同趣旨の記述が見られる.

By the omission of the negative accompanying the preceding verb . . ., but passes into the adverbial sense of: Nought but, no more than, only, merely. (Thus the earlier 'he nis but a child' is now 'he is but a child'; here north. dialects use nobbut prep., conj., and adv. = nought but, not but, 'he is nobbut a child'.)

なお,OED ではLangland (1393) がこの用法の初例となっているが,MED の but (conj. (also quasi adj., adv., and prep.)) 2a によれば,13世紀の The Owl and the Nightingale より例が見られる.

短縮・省略現象としては,ne butan > but の変化は,"negative cycle" として有名なフランス語の ne . . . pas > pas の変化とも類似する.pas は本来「一歩」 (pace) ほどの意味で,直接に否定の意味を担当していた ne と共起して否定を強める働きをしていたが,ne が弱まって失われた結果,pas それ自体が否定の意味を獲得してしまったものである(口語における Ce n'est pas possible. > C'est pas possible. の変化を参照).この pas の経た変化は,本来の意味を失い,否定の意味を獲得したという変化であるから,「#1586. 再分析の下位区分」 ([2013-08-30-1]) で示した Croft の術語でいえば "metanalysis" の例といえそうだ.

確かに,いずれももともと共起していた否定辞が脱落する過程で,否定の意味を獲得したという点では共通しており,統語的な短縮・省略の例であると当時に,意味の観点からは意味の転送 (meaning transfer) とか感染 (contagion) の例とも呼ぶことができそうだ.しかし,but と pas のケースでは,細部において違いがある.前田 (115) から引用しよう(原文の圏点は,ここでは太字にしてある).

ne + pas では,否定辞 ne の意味が pas の本来の意味〈一歩〉と完全に置き換えられたのに対して,この but の発達では,butan の意味はそのまま保持され,そのうえに ne の意味が重畳されている.この例に関して興味深いのは,否定辞 ne は音声的に消えてしまったのに,意味だけがなおも亡霊のように残っている点である.つまり,この but の用法では,省略された要素の意味が重畳されているぶん,but の他の用法に比べて意味が複雑になっている.

したがって,but の経た変化は,Croft のいう "metanalysis" には厳密に当てはまらないように見える.前田は,but の経た変化を,感染 (contagion) ではなく短縮的感染 (contractive contagion) と表現し,pas の変化とは区別している.なお,Stern はいずれのケースも意味変化の類型のなかの Shortening (より細かくは Clipping)の例として挙げている(「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]) を参照).

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

2014-07-28 Mon

■ #1918. sharp と flat [adjective][adverb][antonymy][synaesthesia][semantic_change]

sharp と flat と聞けば,音楽における半音高い嬰記号(♯)と半音低い変記号(♭)が思い浮かぶ.音楽では互いに反意語ともいえる関係だが,おもしろいことに英語では「きっかり,正確に」という意味を共有している.日本語でも flat は「10秒フラットで走る」などという言い方をするが,英語では sharp も「きっかり,正確に」を意味する副詞として用いられる.以下に,両語をこの意味での副詞として用いた例文を挙げよう.

・ We're meeting at one thirty sharp.

・ Please be here at seven o'clock sharp.

・ She planned to unlock the store at 8.00 sharp this morning.

・ He ran 100 yards in 10 seconds flat!

・ You're sitting behind an engine that'll move you from 0 to 60mph in six seconds flat.

・ I fell asleep in five seconds flat!

sharp は時刻を表わすのに,flat は時間計測に用いられるという違いはあるが,「きっかり,正確に」という意味の一致は興味深い.これはどのような理由によるのだろうか.

sharp は「鋭い」の原義から,「(時間に)厳しい,厳格な」を経由して,「きっかり,正確に」へと意味変化した.punctual (時間厳守の)の語幹がラテン語 punctum,すなわち鋭い切っ先をもつ point であることも比較されたい.

flat は原義「平ら」が,おそらく計量における「すりきり」を経由して,「きっかり,正確に」へと意味変化したものではないかと考えられる,ここから,もっぱら計測に用いられる理由がわかる.

つまり,「きっかり,正確に」の語義の獲得に関しては,sharp と flat の間には直接にも間接にも関係がないと考えてよい.それぞれ独自のルートを経て,たまたま似たような語義が発達したと考えられる.

一方,音楽用語としての両語の対立は,また別の話しである.sharp は,声音の甲高さを声音の鋭さとしてとらえた共感覚 (synaesthesia) の産物であり,そこから「(キーについて)半音高い」の語義が生まれた.対する flat は,Shakespeare の The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1. 2. 90) において初出し,「きつい,厳しい」の語義で用いられた sharp ("No, madam, 'tis too sharp.") への皮肉的な返答として,「平凡な,つまらない」を意味する反意語として flat ("Nay, you are too flat.") が用いられたことに由来する.この掛け合いから生じた反意関係が音色の記述としても応用され,「半音高い」のsharp との対比で「半音低い」の flat が生まれた.このように間接的ではあるが,flat のほうも共感覚に訴えかけた成果としての新語義獲得ということになろう.別の言い方をすれば,"correlative analogy" (Stern 218--20) による反意語の形成といえる.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-07-19 Sat

■ #1909. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (2) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics][euphemism][taboo][sapir-whorf_hypothesis]

昨日の記事「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]) で,英語史を通じて見られる semantic pejoration の一大語群を見た.英語史的には,女性を表わす語の意味の悪化は明らかな傾向であり,その背後には何らかの動機づけがあると考えられる.では,どのような動機づけがあるのだろうか.

1つは,とりわけ「売春婦」を指示する婉曲的な語句 (euphemism) の需要が常に存在したという事情がある.売春婦を意味する語は一種の taboo であり,間接的にやんわりとその指示対象を指示することのできる別の語を常に要求する.ある語に一度ネガティヴな含意がまとわりついてしまうと,それを取り払うのは難しいため,話者は手垢のついていない別の語を用いて指示することを選ぶのである.その方法は,「#469. euphemism の作り方」 ([2010-08-09-1]) でみたように様々あるが,既存の語を取り上げて,その意味を転換(下落)させてしまうというのが簡便なやり方の1つである.日本語の「風俗」「夜鷹」もこの類いである.関連して,女性の下着を表わす語の euphemism について「#908. bra, panties, nightie」 ([2011-10-22-1]) を参照されたい.

しかし,Schulz の主張によれば,最大の動機づけは,男性による女性への偏見,要するに女性蔑視の観念であるという.では,なぜ男性が女性を蔑視するかというと,それは男性が女性を恐れているからだという.恐怖の対象である女性の価値を社会的に(そして言語的にも)下げることによって,男性は恐怖から逃れようとしているのだ,と.さらに,なぜ男性は女性を恐れているのかといえば,根源は男性の "fear of sexual inadequacy" にある,と続く.Schulz (89) は複数の論者に依拠しながら,次のように述べる.

A woman knows the truth about his potency; he cannot lie to her. Yet her own performance remains a secret, a mystery to him. Thus, man's fear of woman is basically sexual, which is perhaps the reason why so many of the derogatory terms for women take on sexual connotations.

うーむ,これは恐ろしい.純粋に歴史言語学的な関心からこの意味変化の話題を取り上げたのだが,こんな議論になってくるとは.最初に予想していたよりもずっと学際的なトピックになり得るらしい.認識の言語への反映という観点からは,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) にも関わってきそうだ.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-07-18 Fri

■ #1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1) [semantic_change][gender][lexicology][semantics]

「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) の (3) で示した意味の悪化 (pejoration) は,英語史において例が多い.良い意味,あるいは少なくとも中立的な意味だった語にネガティヴな価値が付される現象である.これまでの記事としては,「#505. silly の意味変化」 ([2010-09-14-1]),「#683. semantic prosody と性悪説」 ([2011-03-11-1] ),「#742. amusing, awful, and artificial」 ([2011-05-09-1]) などで具体例を見てきた.

しかし,英語史における意味の悪化の例としてとりわけよく知られているのは,女性を表わす語彙だろう.英語史を通じて,「女性」を意味する語群は,軒並み侮蔑的な含蓄的意味 (connotation) を獲得していく傾向を示す.「女性」→「性的にだらしない女性」→「娼婦」というのが典型的なパターンである.この話題を正面から扱った Schulz の論文 "The Semantic Derogation of Woman" によると,「女性を表わす語の堕落」がいかに一般的な現象であるかが,これでもかと言わんばかりに示される.3箇所から引用しよう.

Again and again in the history of the language, one finds that a perfectly innocent term designating a girl or woman may begin with totally neutral or even positive connotations, but that gradually it acquires negative implications, at first perhaps only slightly disparaging, but after a period of time becoming abusive and ending as a sexual slur. (82--83)

. . . virtually every originally neutral word for women has at some point in its existence acquired debased connotations or obscene reference, or both. (83)

I have located roughly a thousand words and phrases describing women in sexually derogatory ways. There is nothing approaching this multitude for describing men. Farmer and Henley (1965), for example, have over five hundred terms (in English alone) which are synonyms for prostitute. They have only sixty-five synonyms for whoremonger. (89)

Schulz の論文内には,数多くの例が列挙されている.論文内に現われる99語をアルファベット順に並べてみた.すべてが「性的に堕落した女」「娼婦」にまで意味が悪化したわけではないが,英語史のなかで少なくともある時期に侮蔑的な含意をもって女性を指示し得た単語群である.

abbess, academician, aunt, bag, bat, bawd, beldam, biddy, Biddy, bitch, broad, broadtail, carrion, cat, cleaver, cocktail, courtesan, cousin, cow, crone, dame, daughter, doll, Dolly, dolly, dowager, drab, drap, female, flagger, floozie, frump, game, Gill, girl, governess, guttersnipe, hack, hackney, hag, harlot, harridan, heifer, hussy, jade, jay, Jill, Jude, Jug, Kitty, kitty, lady, laundress, Madam, minx, Miss, Mistress, moonlighter, Mopsy, mother, mutton, natural, needlewoman, niece, nun, nymph, nymphet, omnibus, peach, pig, pinchprick, pirate, plover, Polly, princess, professional, Pug, quean, sister, slattern, slut, sow, spinster, squaw, sweetheart, tail trader, Tart, tickletail, tit, tramp, trollop, trot, twofer, underwear, warhorse, wench, whore, wife, witch

重要なのは,これらに対応する男性を表わす語群は必ずしも意味の悪化を被っていないことだ.spinster (独身女性)に対する bachelor (独身男性),witch (魔女)に対する warlock (男の魔法使い)はネガティヴな含意はないし,どちらかというとポジティヴな評価を付されている.老女性を表わす trot, heifer などは侮蔑的だが,老男性を表わす geezer, codger は少々侮蔑的だとしてもその度合いは小さい.queen (女王)は quean (あばずれ女)と通じ,Byron は "the Queen of queans" などと言葉遊びをしているが,対する king (王)には侮蔑の含意はない.princess と prince も同様に対照的だ.mother, sister, aunt, niece の意味は堕落したことがあったが,対応する father, brother, uncle, nephew にはその気味はない.男性の職業・役割を表わす footman, yeoman, squire は意味の下落を免れるが,abbess, hussy, needlewoman など女性の職業・役割の多くは professional その語が示しているように,容易に「夜の職業」へと転化してゆく.若い男性を表わす語は boy, youth, stripling, lad, fellow, puppy, whelp など中立的だが,doll, girl, nymph は侮蔑的となる.

女性を表わす固有名詞も,しばしば意味の悪化の対象となる.また,男性と女性の両者を指示することができる dog, pig, pirate などの語でも,女性を指示する場合には,ネガティヴな意味が付されるものも少なくない.いやはや,随分と類義語を生み出してきたものである.

・ Schulz, Muriel. "The Semantic Derogation of Woman." Language and Sex: Difference and Dominance. Ed. Barrie Thorne and Nancy Henley. Rowley, MA: Newbury House, 1975. 64--75.

2014-06-14 Sat

■ #1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性 [semantics][semantic_change][frequency][speed_of_change]

高頻度語は形態的に保守的だということは,よくいわれる.頻度と変化しやすさとの間に相関関係があるらしいことは,最近でも「#1864. ら抜き言葉と頻度効果」 ([2014-06-04-1]) で取り上げ,その記事の冒頭にもいくつかの記事へのリンクを張った (##694,1091,1239,1242,1243,1265,1286,1287,1864) .高頻度語はたいてい日常的な基礎語でもあることから,この問題は基礎語彙の保守性という問題にも通じる.実際,「#1128. glottochronology」 ([2012-05-29-1]) は,基礎語彙の保守性を前提とした仮説だった.

語という記号 (sign) や形態という記号表現 (signifiant) について頻度と保守性の関係が指摘されるのならば,記号のもう1つの側面である記号内容 (signifié),すなわち意味についても同様の関係が指摘されてもよいはずだ.高頻度の意味であれば,変化しにくいといえるのではないか.Stern (185) は,高頻度語の語義の保守性に触れている.

It is well known that the most common words of a language retain most tenaciously old and otherwise discarded forms and inflections. It is reasonable to assume that a strong tradition has similar effects on meanings. Note, however, that the retention of one or more old meanings is no obstacle to the acquisition of new ones: frequency is only a conservative factor for already established meanings.

高頻度の語義をもつ語はそれ自体が高頻度であり,日常的な基礎語である確率が高く,全体として保守的だろうとは予想される.しかし,なるほど Stern の述べる通り,その高頻度の語義は保守的だとしても,その語に比喩的・派生的な語義が新たに付加されることが妨げられるわけではない.むしろ,多くの場合,基礎語は多義である.

Stern の言うように,形態についても意味についても,高頻度と保守性との相関関係は等しく認められるように思われる.しかし,1つ大きな違いがある.形態の変化を論じる場合には,新形が旧形に取って代わる過程,あるいは少なくとも両形が variants として並び立つ状況が前提とされる.一応のところ 各々の variant は明確に区別される.しかし,意味の変化を論じる場合には,新しい語義が古い語義を必ずしも置き換えるのではなく,その上に累積されてゆくことが多い.新旧 variants の置換や並立というよりは,それらが多義として積み重なっていく過程である.形態の保守性と意味の保守性は,この違いを意識しながら理解しておく必要があるだろう.関連して,「#1692. 意味と形態の関係」 ([2013-12-14-1]) の第3引用を参照されたい.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-06-13 Fri

■ #1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類 [semantics][semantic_change][causation]

「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]),「#1863. Stern による語の意味を決定づける3要素」 ([2014-06-03-1]),「#1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能」 ([2014-06-02-1]) で,意味と意味変化について考察した Stern の見解を紹介してきた.Stern (165--76) は意味変化の分類をも手がけ,7種類の分類を提案した.

A. External Causes Class I. Substitution.

B. Linguistic Causes

I. Shift of Verbal Relation

a. Class II. Analogy.

b. Class III. Shortening.

II. Shift of Referential Relation

a. Class IV. Nomination.

b. Class V. (Regular) Transfer.

III. Shift of Subjective Relation

a. Class VI. Permutation.

b. Class VII. Adequation.

Class I (Substitution) は,外部的,非言語的な要因による意味変化である.しばしば技術や文化の発展が関わっており,例えば ship や to travel は,近代的な乗り物が発明される前と後とでは,指示対象 (referent) が異なっている.意味変化そのものとみなすよりは,指示対象の変化に伴う意味の変更といったほうが適切かもしれない.

Class II (Analogy) は,例えば副詞 fast が「しっかりと」から「速く」へとたどった意味変化が,類推により対応する形容詞 fast へも影響し,形容詞 fast も「速い」の語義を獲得したという事例が挙げられる.意図的,非意図的の両方があり得る.話者主体.

Class III (Shortening) は,private soldier の省略形として private が用いれるようなケースで,結果として private の意味や機能が変化したことになる.意図的,非意図的の両方があり得る.話者主体.

Class IV (Nomination) は,いわゆる暗喩,換喩,提喩などを含む転義だが,とりわけ詩人などが意図的(ときに恣意的)に行う臨時的な転義を指す.話者主体.

Class V ((Regular) Transfer) は,意図的な転義を表わす Nomination に対して,非意図的な転義を指す.しかし,意図の有無が判然としないケースもある.話者主体.

Class VI (Permutation) は,count one's beads という「句」において,元来 beads は祈りを意味したが,祈りの回数を数えるのにロザリオの数珠玉をもってしたことから,beads が数珠玉そのものを意味するようになった.count one's beads は,両義に解釈できるという点で曖昧ではあるが,祈りながら数珠玉を数えている状況全体を指示対象としているという特徴がある.非意図的.聞き手も多く関与する.

Class VII (Adequation) は,元来動物の角を表わす horn という「語」が,(材質を問わない)角笛を意味するようになった例が挙げられる.指示対象自体は変化していないので Substitution ではなく,指示対象の使用目的に関する話者の理解が変化した点が特徴的である.非意図的.聞き手も多く関与する.

Stern の7分類は,(1) 言語外的か内的か,(2) 言語手段,指示対象,主観のいずれに関わるか,(3) 意図的か非意図的か,(4) 主たる参与者か話者のみか聞き手も含むか,といった複数の基準を重ね合わせたものである.1つのモデルとしてとらえておきたい.

関連して,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]) も参照.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-06-02 Mon

■ #1862. Stern による言語の4つの機能 [function_of_language][semantic_change]

Stern (21) は「#1776. Ogden and Richards による言語の5つの機能」 ([2014-03-08-1]) を部分的に批判しながらも,彼らの全体的な主張には同調しつつ,言語の最も重要な機能は,ある目的・効果を達成することであると考えている.Stern は,言語の諸機能間の相互関係については未詳としながらも,この "effective function" に特別な地位を与えている.

The effective function must, I think, be the most important of the primary functions, for if, for instance, the words I am writing here are to have the intended effect on the readers, they must (1) symbolize certain referents, i. e., the topic which I am discussing; (2) express my views of it, and (3) communicate this to the readers; only if these three functions are filled, can speech (4) perform its effective function, which is thus founded on the others. (Stern 20--21)

[2014-03-08-1]の記事に示した Ogden and Richards の諸機能の分類でいえば,およそ (i) が Stern の (1) に相当し,(ii), (iii) が (2) に相当し,(iv) が (3), (4) に相当するということになろう.いずれにせよ,指示対象 (referent),話し手 (addresser),聞き手 (addressee) の言語行動に関わる3者それぞれに働きかける3機能とまとめてよいだろう.関連して,「#1070. Jakobson による言語行動に不可欠な6つの構成要素」 ([2012-04-01-1]) および「#1071. Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」 ([2012-04-02-1]) の記事を参照されたい.

3者3機能ということでいえば,Stern (21) が脚注で参照している心理学者 Karl Bühler も,上記におよそ対応する言語の3機能を唱えている.Bühler によれば,その3つとは Kundgabe "expression", Auslösung (release), Darstellung (description) である.それぞれ,Stern の "expressive", "purposive", "symbolic" 機能に相当する.

Stern にせよ Ogden and Richards にせよ Bühler にせよ,言語とは「指示対象に相当する語を複数並べ,そこに自らの思いを託しながら相手に伝え,相手を動かす」ための道具ということになる.どんな言語分析もある種の言語観に基づいているとするならば,言語の機能をどう考えるかという問題は,すべての言語分析者にとって最重要の課題といえるだろう.

より一般的に知られている言語の諸機能については「#1071. Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」 ([2012-04-02-1]) や「#523. 言語の機能と言語の変化」 ([2010-10-02-1]) を参照されたい.また,Jakobson への批判および言語の諸機能の分類への一般的な反論としては,「#1259. 「Jakobson による言語の6つの機能」への批判」 ([2012-10-07-1]) をどうぞ.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-04-02 Wed

■ #1801. homonymy と polysemy の境 [semantics][homonymy][polysemy][semantic_change][lexeme][componential_analysis]

homonymy (同義)と polysemy (多義)の区別が難しいことについては,「#286. homonymy, homophony, homography, polysemy」 ([2010-02-07-1]) や「#815. polysemic clash?」 ([2011-07-21-1]) の記事で話題にした.同形態の2つの語彙素が2つの同義語であるのか,あるいは1つの多義語であるのかは,一方は通時的な意味の変遷を参考にして,他方では話者の共時的な直感を参考にして判断するというのが通常の態度だろう.しかし,2つの視点が食い違うこともある.

例えば,(トランプの)組札,(衣服の)スーツ,訴訟の3つの語義をもつ suit という語を考えよう.3者は語源的には関連があり,核となる意味として "a following or natural sequence of things or events" ほどをもつ.「組札」と「スーツ」は一組・一続きという共通項でくくられそうだが,「訴訟」は原義からが逸脱しているように思われる.「訴訟」は「不正をただす目的で自然な流れとして法廷に訴える」に由来し,本来的には原義とつながりは保っているのだが,共時的な感覚としては逸脱としているといってよいだろう.Voyles (121--22) は,生成意味論の立場から,3つの語義が1つの語として共存しえた段階の意味規則を (1) として,2つの語に分かれたというに近い現代の段階の意味規則を (2) として定式化した.

(1) が polysemous,(2) が homonymous ということになるが,(2) も全体をひとくくりにしているという点では,必ずしも2つの別の語とみなしているわけではないのかもしれない.ポイントは,homonymy か polysemy かの区別は程度の問題ということである.Voyles (122) 曰く,

We are suggesting that for most contemporary speakers the meaning of suit as a set of cards or a set of clothes is an instance of polysemy: these two meanings share certain semantic markers in common. The other meaning of 'legal action' has become completely divorced from the meaning of 'collection' in that it has virtually no features in common with this meaning. This is then an instance of homonymy. The question of whether two or more different sense of a word should be considered the same or separate lexical items is, we believe, a function of the number of semantic features shared by the two (or more) senses. Often such a question does not admit of a simple yes or no; rather, the answer is one of degree.

生成意味論での意味変化の考え方について,一言述べておこう.Voyles によれば,意味素性の束から成る語の意味表示に対して,ある意味素性を加えたり,脱落させたりする規則を適用することによって,その語の意味が変化すると考えた.生成文法が意味を扱う際に常にアキレス腱となるのは,どの意味素性を普遍的な意味素性として設定するかという問題である.Voyles (122) も,結局,同じ問題にぶつかっているようだ.Williams (462) による Voyles の論文に対する評は,否定的だ.

A formal system for representing semantic structure is no less a prerequisite to describing most patterns in change of meaning. Voyles 1973 has attempted to represent change of meaning, building on the formal semantic theory of features and markers first proposed by Katz & Fodor 1963. He tries to demonstrate that semantic change can be systematically explained by changes in rules that generate semantic representations, much as phonological change can be represented as rule change. But a great deal of investigation is still necessary before we understand what should go into a semantic representation, much less what one should look like and how it might change.

生成意味論は理論的には過去のものといってよいだろう.しかし,homonymy と polysemy のような個別の問題については,どんな理論も何らかのヒントは与えてくれるものである.

・ Voyles, Joseph. "Accounting for Semantic Change." Lingua 31 (1973): 95--124.

・ Williams, Joseph M. "Synaesthetic Adjectives: A Possible Law of Semantic Change." Language 52 (1976): 461--78.

2014-02-27 Thu

■ #1767. 固有名詞→普通名詞→人称代名詞の一部と変化してきた guy [etymology][history][personal_pronoun][semantic_change]

先日の記事「#1750. bonfire」 ([2014-02-10-1]) で触れたが,イギリスでは11月5日は Bonfire Night あるいは Guy Fawkes Night と呼ばれ,花火や爆竹を打ち鳴らすお祭りが催される.

James I の統治下の1605年同日,プロテスタントによる迫害に不満を抱くカトリックの分子が,議会の爆破と James I 暗殺をもくろんだ.世に言う火薬陰謀事件 (Gunpowder Plot) である.主導者 Robert Catesby が募った工作員 (gunpowder plotters) のなかで,議会爆破の実行係として選ばれたのが,有能な闘志 Guy Fawkes だった.11月4日の夜から5日の未明にかけて,Guy Fawkes は1トンほどの爆薬とともに議会の地下室に潜み,実行のときを待っていた.しかし,その陰謀は未然に発覚するに至った.5日には,James I が,ある種の神託を受けたかのように,未遂事件の後始末としてロンドン市民に焚き火を燃やすよう,お触れを出した.なお,gunpowder plotters はすぐに捕えられ,翌年の1月末までに Guy Fawkes を含め,みな処刑されることとなった.

事件以降,この日に焚き火の祭りを催す風習が定着していった.17世紀半ばには,花火を打ち上げたり,Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形を燃やす風習も確認される.本来の趣旨としては,あのテロ未遂の日を忘れるなということなのだが,趣旨が歴史のなかでおぼろげとなり,現在の風習に至った.Oxford Dictionary of National Biography の "Gunpowder plotters" の項によれば,次のように評されている. * * * *

. . . the memory of the Gunpowder Plot, or rather the frustration of the plot, has offered a half-understood excuse for grand, organized spectacle on autumnal nights. Even today, though, the underlying message of deliverance and the excitement of fireworks and bonfires sit alongside the tantalizing what-ifs, and a sneaking respect for Guy Fawkes and his now largely forgotten coconspirators.

さて,Guy という人名はフランス語由来 (cf. Guy de Maupassant) だが,イタリア語 Guido などとも同根で,究極的にはゲルマン系のようだ.語源的には guide や guy (ロープ)とも関連する.この固有名詞は,19世紀に,「Guy Fawkes をかたどった人形」の意で用いられるようになり,さらにこの人形は奇妙な衣装を着せられることが多かったために,「奇妙な衣装をまとった人」ほどの意が発展した.さらに,より一般化して「人,やつ」ほどの意味が生じ,19世紀末にはとりわけアメリカで広く使われるようになった.固有名詞から普通名詞へと意味・用法が一般化した例の1つである.この意味変化を Barnhart の語源辞書の記述により,再度,追っておこう.

guy2 n. Informal. man, fellow. 1847, from earlier guy a grotesquely or poorly dressed person (1836); originally, a grotesquely dressed effigy of Guy Fawkes (1806; Fawkes, 1570--1606, was leader of the Gunpowder Plot to blow up the British king and Parliament in 1605). The meaning of man or fellow originated in Great Britain but became popular in the United States in the late 1800's; it was first recorded in American English in George Ade's Artie (1896).

口語的な "fellow" ほどの意味で用いられる guy は,20世紀には you guys の形で広く用いられるようになってきた.you guys という表現は,「#529. 現代非標準変種の2人称複数代名詞」 ([2010-10-08-1]) やその他の記事 (you guys) で取り上げてきたように,すでに口語的な2人称複数代名詞と呼んで差し支えないほどに一般化している.ここでの guy は,人称代名詞の形態の一部として機能しているにすぎない.

あの歴史的事件から400年余が経った.Guy Fawkes の名前は,意味変化の気まぐれにより,現代英語の根幹にその痕跡を残している.

・ Barnhart, Robert K. and Sol Steimetz, eds. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. Bronxville, NY: The H. W. Wilson, 1988.

2014-02-19 Wed

■ #1759. synaesthesia の方向性 [synaesthesia][semantic_change][semantics]

この2日間の記事 ([2014-02-17-1], [2014-02-18-1]) で,18世紀後半から19世紀にかけてのロマン派と synaesthesia 表現の関係について見てきた.言語学的あるいは意味論的にいえば,synaesthesia 表現のもつ最大の魅力は,「下位感覚から上位感覚への意味転用」という方向性,あるいは,背伸びした表現でいえば,法則性にある.

この方向性についての仮説を,英語の共感覚表現によって精緻に実証し,論考したのが,Williams である.Williams は,100を超える感覚を表わす英語の形容詞について,関連する語義の初出年代を OED や MED で確かめながら,意味の転用の通時的傾向を明らかにした.さらに,英語に限っていえば,単に下位から上位への転用という一般論を述べるだけではなく,特定の感覚間での転用が目立つという点をも明らかにした.Williams (463) の結論は明快である.

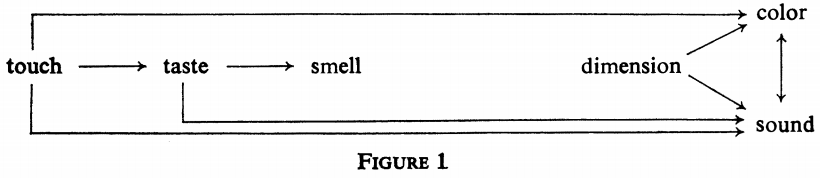

THE MAJOR GENERALIZATION is this: if a lexeme metaphorically transfers from its earliest sensory meaning to another sensory modality, it will transfer according to the schedule shown in Figure 1.

この方向性を,生理学的な観点から表現すれば,"Sensory words in English have systematically transferred from the physiologically least differentiating, most evolutionary primitive sensory modalities to the most differentiating, most advanced, but not vice versa." (Williams 464--65) となる.Williams (464) より,具体的な形容詞を挙げる.

TOUCH TO TASTE: aspre, bitter, bland, cloying, coarse, cold, cool, dry, hard, harsh, keen, mild, piquant, poignant, sharp, smooth.

TOUCH TO COLOR: dull, light, warm.

TOUCH TO SOUND: grave, heavy, rough, smart, soft.

TASTE TO SMELL: acrid, sour, sweet.

TASTE TO SOUND: brisk, dulcet.

DIMENSION TO COLOR: full.

DIMENSION TO SOUND: acute, big, deep, empty, even, fat, flat, high, hollow, level, little, low, shallow, thick.

COLOR TO SOUND: bright, brilliant, clear, dark, dim, faint, light, vivid.

SOUND TO COLOR: quiet, strident.

もちろん,Ullmann のロマン派詩人の調査にも見られたように,この方向性に例外がないわけではない.Williams (464) は,以下の例外リストを挙げている.

TOUCH TO DIMENSION: crisp.

TOUCH TO SMELL: hot, pungent.

TASTE TO TOUCH: eager, tart.

TASTE TO COLOR: austere, mellow.

DIMENSION TO TASTE: thin.

DIMENSION TO TOUCH: small.

SOUND TO TASTE: loud.

SOUND TO TOUCH: shrill.

Williams は,この仮説に沿う共感覚表現は,数え方にもよるが,全体の83--99%であると述べている.しかし,ここまで高い率であれば,少なくとも傾向とは呼べるし,さらには一種の法則に近いものとみなしても差し支えないだろう.

Williams (470--72) は,この仮説の大筋は他言語にも当てはまるはずだと見込んでおり,実際に日本語の共感覚表現について『広辞苑』と日本語母語話者インフォーマントを用いて,同じ方向性を91%という整合率を挙げながら確認している.

この意味転用の方向性の仮説が興味を引く1つの点は,嗅覚 (smell) がどん詰まりであるということだ.嗅覚からの転用はないということになるが,これは印欧語にも日本語にも言えることである.また,touch -> taste -> smell の方向性についていえば,アリストテレスが味覚 (taste) は特殊な触覚 (touch) であると考えたことと響き合い,一方,味覚 (taste) は嗅覚 (smell) と近いために前者が後者に用語を貸し出していると解釈することができるかもしれない (Williams 472) .言語的な共感覚表現と,人類進化論や生理学との平行性に注目しながら,Williams (473) はこう述べている.

Though I do not suggest that Fig. 1 represents more than chronological sequence, the 'dead-end' appearance of the olfactory sense is a striking visual metaphor for the evolutionary history of man's sensory development.

論文の最後で,Williams (473--74) は「意味法則」([2014-02-16-1]の記事「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」を参照)への自信を覗かせている.

. . . what is offered here constitutes not only a description of a rule-governed semantic change through the last 1200 years of English---a regularity that qualifies for lawhood, as the term LAW has ordinarily been used in historical linguistics---but also as a testable hypothesis in regard to past or future changes in any language.

・ Williams, Joseph M. "Synaethetic Adjectives: A Possible Law of Semantic Change." Language 52 (1976): 461--78.

2014-02-18 Tue

■ #1758. synaesthesia とロマン派詩人 (2) [synaesthesia][semantic_change][semantics][rhetoric][literature]

昨日の記事「#1757. synaesthesia とロマン派詩人 (1)」 ([2014-02-17-1]) に引き続き,共感覚表現とロマン派詩人について.

Ullmann (281) に,2人のロマン派詩人 Keats と Gautier の作品をコーパスとした synaesthesia の調査結果が掲載されている.収集した共感覚表現において,6つの感覚のいずれからいずれへの意味の転用がそれぞれ何例あるかを集計したものである.表の見方は,最初の Keats の表でいえば,Touch -> Sound の転用が39例あるという読みになる.

| Keats | Touch | Heat | Taste | Scent | Sound | Sight | Total |

| Touch | - | 1 | - | 2 | 39 | 14 | 56 |

| Heat | 2 | - | - | 1 | 5 | 11 | 19 |

| Taste | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 17 | 16 | 36 |

| Scent | 2 | - | 1 | - | 2 | 5 | 10 |

| Sound | - | - | - | - | - | 12 | 12 |

| Sight | 6 | 2 | 1 | - | 31 | - | 40 |

| Total | 11 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 94 | 58 | 173 |

| Gautier | Touch | Heat | Taste | Scent | Sound | Sight | Total |

| Touch | - | 5 | - | 5 | 70 | 55 | 135 |

| Heat | - | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | 15 |

| Taste | - | - | - | 4 | 11 | 7 | 22 |

| Scent | - | - | - | - | 5 | 1 | 6 |

| Sound | 2 | 1 | - | 1 | - | 13 | 17 |

| Sight | 3 | - | - | 1 | 34 | - | 38 |

| Total | 5 | 6 | - | 11 | 124 | 87 | 233 |

多少のむらがあるとは言え,表の左上から右下に引いた対角線の右上部に数が集まっているということがわかるだろう.とりわけ Touch -> Sound や Touch -> Sight が多い.これは,共感覚表現を生み出す意味の転用は,主として下位感覚から上位感覚の方向に生じることが多いことを示す.生理学的には最高次の感覚は Sound ではなく Sight と考えられるので,Touch -> Sound のほうが多いのは,この傾向に反するようにもみえるが,Ullmann (283) はこの理由について以下のように述べている.

Visual terminology is incomparably richer than its auditional counterpart, and has also far more similes and images at its command. Of the two sensory domains at the top end of the scale, sound stands more in need of external support than light, form, or colour; hence the greater frequency of the intrusion of outside elements into the description of acoustic phenomena.

さらに,Ullmann (282) は,他の作家も含めた以下の調査結果を提示している.下位感覚から上位感覚への転用を Upward,その逆を Downward として例数を数え,上述の傾向を補強している.

| Author | Upward | Downward | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Byron | 175 | 33 | 208 |

| Keats | 126 | 47 | 173 |

| Morris | 279 | 23 | 302 |

| Wilde | 337 | 77 | 414 |

| 'Decadents' | 335 | 75 | 410 |

| Longfellow | 78 | 26 | 104 |

| Leconte de Lisle | 143 | 22 | 165 |

| Gautier | 192 | 41 | 233 |

| Total | 1,665 | 344 | 2,009 |

synaesthesia の言語的研究は,この Ullmann (266--89) の調査とそこから導き出された傾向が契機となって,研究者の関心を集めるようになった.下位感覚から上位感覚への意味の転用という仮説は,通時的にも通言語的に概ね当てはまるとされ,一種の「意味変化の法則」([2014-02-16-1]の記事「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」を参照)をなすものとして注目されている.心理学,認知科学,生理学,進化論などの立場からの知見と合わせて,学際的に扱われるべき研究領域といえよう.

関連して,音を色や形として認識することのできる能力をもつ話者に関する研究として,Jakobson, R., G. A. Reichard, and E. Werth の論文を挙げておく.

・ Ullmann, Stephen. The Principles of Semantics. 2nd ed. Glasgow: Jackson, 1957.

・ Jakobson, R., G. A. Reichard, and E. Werth. "Language and Synaesthesia." Word 5 (1949): 224--33.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow