2015-12-13 Sun

■ #2421. 現在分詞と動名詞の協働的発達 [gerund][participle][syntax][suffix]

現代英語では,現在分詞 (present participle) と動名詞 (gerund) は同じ -ing 語尾をとるが,その機能は画然と分かれている.この2つの準動詞を一括して「-ing 形」と呼ぶ文法家もいるが,伝統的に呼び分けてきたのには歴史的な事情がある.古くは現在分詞と動名詞は,機能の差違はさることながら,形態的にも明確に異なっていた.つまり,この2種類の準動詞は,当初は完全に独立していたが,後の歴史で互いに歩み寄ってきたという経緯がある.以下,中尾・児馬 (118--20, 187--91) を参照して,教科書的な説明を与えよう.

古英語では,現在動名詞と呼ぶところの機能は,to 付きの不定詞によって表わされていた.動詞に接尾辞 -ing を付加した形態はあるにはあったが,この接尾辞は純粋に名詞を作る語尾であり,作られた名詞は,現在の動名詞と異なり,動詞としての性質をほとんどもたない純然たる名詞だった.この状態は,ほぼ中英語期のあいだ続く.中英語後期から近代英語期にかけて,ようやく -ing 形は (1) 目的語を従え,(2) 副詞と共起し,(3) 完了形や受動態も可能となり,(4) 通格の主語を取るなど,動詞的な性格を帯びるようになった.このように,動名詞は派生名詞として出発したが,時とともに少しずつ動詞としての性格を獲得していった文法項目とみることができる.

一方,現在分詞は,古英語から中英語を通じて,-inde, -ende, -ande などの語尾を伴って存在した(語尾の変異については中英語の方言差を扱った「#790. 中英語方言における動詞屈折語尾の分布」 ([2011-06-26-1]) と,そこに挙げた地図を参照).変異形のなかでも -inde は,末尾が弱まれば容易に /in/ となっただろう.一方,動名詞語尾の -ing も末尾が弱まれば同様に /in/ となるから,動名詞と現在分詞は音韻形態的に融合する可能性を秘めていたと考えることができる.

音韻形態的な融合の可能性を受け入れるとして,では両者の機能上の接点はどこにあるだろうか.標準的な説によれば,橋渡しをしたのは「be + (on) + -ing」という構文であると考えられている.古英語より「bēon + -inde」などの統語構造が行なわれていたが,13世紀以降,上記の音韻形態上の融合により「be + -ing」が現われてくる.一方,古英語では,前置詞と -ing 名詞を用いた「bēon + on + -ing」の構文も行なわれていた.ここから前置詞 on が音韻的に弱化し,[on] > [ən] > [ə] > [ø] と最終的に消失してしまうと,結果的にこの構文は先の構文と同型の「be + -ing」へ収斂した.この段階において,後に動名詞および現在分詞と呼ばれることになる2つの準動詞が,音韻・形態・統語的に結びつけられることになったのである.

上記の発展の過程を,現代英語の文により比喩的に示せば,以下の通りになる.3文の表わす意味の近似に注意されたい.

(a) The king is on hunting.

(b) The king is a-hunting.

(c) The king is hunting.

まとめれば,現在分詞と動名詞は,音韻・形態・統語の各側面において相互に作用しながら,協働的に発達してきたということができる.元来現在分詞を表わす -inde は動名詞に動詞的な性格を与え,元来名詞を表わす -ing は現在分詞にその音韻形態を貸し出したのである.

・ 中尾 俊夫・児馬 修(編著) 『歴史的にさぐる現代の英文法』 大修館,1990年.

2015-09-25 Fri

■ #2342. 学問名につく -ic と -ics [plural][greek][latin][french][loan_word][suffix][renaissance]

学問名には,acoustics, aesthetics, bionomics, conics, dynamics, economics, electronics, ethics, genetics, linguistics, mathematics, metaphysics, optics, phonetics, physics, politics, statics, statistics, tectonics のように接尾辞 -ics のつくものが圧倒的に多いが,-ic で終わる arithmetic, logic, magic, music, rhetoric のような例も少数ある.近年,dialectic(s), dogmatic(s), ethic(s), metaphysic(s), physic(s), static(s) など,従来の -ics に対して,ドイツ語やフランス語の用法に影響されて -ic を用いる書き手も出てきており,ややこしい.

-ic と -ics の違いは,端的にいえば形容詞から転換した名詞の単数形と複数形の違いである.「?に関する」を意味する形容詞を名詞化して「?に関すること」とし,場合によってはさらに複数形にして「?に関する事々」として,全体として当該の知識や学問を表わすという語源だ.しかし,実際上,単数と複数のあいだに意味的な区別がつけられているわけでもないので,混乱を招きやすい.

-ic と -ics のいずれかを取るかという問題は,意味というよりは,形態の歴史に照らして考える必要がある.その淵源であるギリシア語まで遡ってみよう.ギリシア語では,学問名は technē, theōria, philosophia など女性名詞で表わされるのが普通であり,形容詞接尾辞 -ikos に由来する学問名もその女性形 -ikē を伴って表わされた.ēthikē, mousikē, optikē, rētorikē の如くである.

一方,-ikos の中性複数形 -ika は「?に関する事々」ほどの原義をもち,冠詞を伴って論文の題名として用いられることがあった (ex. ta politikē) .論文の題名は,そのまま学問名へと意味的な発展を遂げることがあったため,この中性複数形の -ika と先の女性単数形 -ikē はときに学問名を表わす同義となった (ex. physikē / physika, taktikē / taktika) .

これらの語がラテン語へ借用されたとき,さらなる混同が生じた.ギリシア語の -ika と -ikē は,ラテン語では同形の -ica として借用されたのである.中世ラテン語では,本来的にこれらの語が単数形に由来するのか複数形に由来するのか,区別がつかなくなった.後のロマンス諸語やドイツ語では,これらは一貫して単数(女性)形に由来するものと解釈され,現在に至る.

英語では,1500年以前の借用語に関しては,単数形と解釈され,フランス語に倣う形で arsmetike, economique, ethyque, logike, magike, mathematique, mechanique, musike, retorique などと綴られた.しかし,15世紀から,ギリシア語の中性複数形に遡るという解釈に基づき,その英語のなぞりとして etiques などの形が現われる.16世紀後半からは,ギリシア語でもたどった過程,すなわち論文名を経由して学問名へと発展する過程が,英語でも繰り返され,1600年以降は,-ics が学問名を表わす一般的な接尾辞として定着していく.-ics の学問名は,形態上は複数形をとるが,現代英語では統語・意味上では単数扱いとなっている.

大雑把にいえば,英語にとって古い学問は -ic,新しい学問は -ics という分布を示すことになるが,その境目が16世紀辺りという点が興味深い.これも,古典語への憧憬に特徴づけられた英国ルネサンスの言語的反映かもしれない.

2015-08-01 Sat

■ #2287. chicken, kitten, maiden [suffix][norman_french][etymology][i-mutation][germanic]

表記の3語は,いずれも -en という指小辞 (diminutive) を示す.この指小辞は,ゲルマン祖語の中性接尾辞 *-īnam (neut.) に遡る.したがって,古英語の文証される cicen と mægden は中性名詞である.

chicken の音韻形態の発達は完全には明らかにされていないが,ゲルマン祖語 *kiukīno に遡るとされる.語幹の *kiuk- は,*kuk- が,接尾辞に生じる前舌高母音の影響下で i-mutation を経たもので,この語根からは cock も生じた.古英語では cicen などとして文証される (cf. Du. kuiken, G Küken, ON kjúklingr) .問題の接尾辞が脱落した chike (> PDE chick) は「ひよこ;ひな」の意味で,後期中英語に初出する.

kitten は,古フランス語 chitoun, cheton (cf. 現代フランス語 chaton) のアングロ・ノルマン形 *kitoun, *ketun を後期中英語期に借用したものとされる.本来的には -o(u)n という語尾を示し,今回話題にしている接尾辞とは無関係だったが,17世紀頃に形態的にも機能的にも指小辞 -en と同化した.

maiden (乙女)は,古英語で mægden などとして文証される.mægden が初期中英語までに語尾を脱落させて生じたのが mæide であり,これが現代の maid に連なる.つまり,古英語に先立つ時代において maid への接辞添加により maiden が生じたと考えられるが,実際に英語史上の文証される順序は,maiden が先であり,そこから語尾消失で maid が生じたということである.両形は現在に至るまで「少女,乙女」の意味をもって共存している.いずれもゲルマン祖語 *maȝaðiz (少女,乙女)に遡り,ここからは関連する古英語 magð (少女,女性)も生じている.さらに,「少女,乙女」を表わす現代英語 may (< OE mǣġ (kinswoman)) も同根と考えられ,関連語の形態と意味を巡る状況は複雑である.なお,maid は中英語では「未婚の男子」を表わすこともあった.

接尾辞 -en には他にも起源を異にする様々なタイプがある.「#1471. golden を生み出した音韻・形態変化」 ([2013-05-07-1]),「#1877. 動詞を作る接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en」 ([2014-06-17-1]),「#2221. vixen の女性語尾」 ([2015-05-27-1]) を参照.

2015-05-27 Wed

■ #2221. vixen の女性語尾 [suffix][gender][i-mutation][germanic][etymology]

「#2219. vane, vat, vixen」 ([2015-05-25-1]) と「#2220. 中英語の中部・北部方言で語頭摩擦音有声化が起こらなかった理由」 ([2015-05-26-1]) で,vixen (雌ギツネ)という語に触れた.現代標準英語の語彙のなかで,語頭の有声摩擦音が歴史的に特異であると述べてきたが,この語にはもう1つ歴史的に特異な点がある.それは,古いゲルマン語の女性名詞語尾に由来する -en をとどめている点だ.

現在,男性名詞から対応する女性名詞を作る主たる接尾辞として -ess がある.これは,ギリシア語 -issa を後期ラテン語が借用した -issa が,フランス語経由で -esse として英語に入ってきたものであり,外来である.ゲルマン系のものとしては「#2188. spinster, youngster などにみられる接尾辞 -ster」 ([2015-04-24-1]) で触れた西ゲルマン語群にみられる -estre があるが,純粋に女性を表わすものとして現代に伝わるのは spinster のみである.今回問題にしている -en もゲルマン語派にみられる女性接尾辞であり,ゲルマン祖語の *-inī, *-injō が古英語の -en, -in へ発展したものである.古英語の類例としては,god (god) に対する gyden (goddess),munuc (monk) に対する mynecen (nun), wulf (wolf) に対する wylfen (she-wolf) がある(いずれも接尾辞に歴史的に含まれていた i による i-mutation の効果に注意).

vixen に関していえば,雌ギツネを意味する名詞としては,古英語には斜格としての fyxan が1例のみ文証されるにすぎない.MED の fixen (n.) によると,初期中英語では fixen が現われるが,fixen hyd (fox hide) として用いられていることから,この形態は古英語の女性形名詞ではなく形容詞 fyxen (of the fox) に由来するとも考えられるかもしれない.しかし,後期中英語では名詞としての ffixen が確かに文証され,『英語語源辞典』によれば,さらに16世紀末以降には語頭の有声摩擦音を示す現在の vyxen に連なる形態が現われるようになる(OED によれば15世紀にも).

現代ドイツ語では女性語尾としての -in は現役であり,Fuchs vs Füchsin のみならず,Student vs Studentin, Sänger vs Sängerin など一般的に用いられる.英語では女性語尾の痕跡は vixen に残るのみとなってしまったが,ゲルマン語の語形成の伝統をかろうじて伝える語として,英語史に話題を提供してくれる貴重な例である.語頭の v と合わせて,英語史的に堪能したい.

2015-05-09 Sat

■ #2203. twentieth の綴字と発音 [suffix][numeral][shakespeare]

序数詞を作る接尾辞に -th がある.最初の3つの序数詞 first, second, third は「#67. 序数詞における補充法」 ([2009-07-04-1]) でみたように語尾が特殊であり,fifth, twelfth も「#1080. なぜ five の序数詞は fifth なのか?」 ([2012-04-11-1]) でみたように基数詞の語幹末子音が無声化している点で例外的にみえるが,その他は基本的には基数詞に -th をつければよい.fourth, tenth, hundredth, millionth のごとく規則的である.

しかし,規則のなかの不規則と呼びうるものに,twentieth から ninetieth までの8つの -ieth 語尾がある.twentieth でいえば,発音は */ˈtwentiθ/ ならぬ /ˈtwentiəθ/ であり,序数詞語尾の e が発音されるために,全体として3音節となることに注意したい.なぜ素直に twenty + th の綴字および発音にならないのだろうか.

古英語では,20, 30, 40 . . . の基数詞は twēntiġ, þrītiġ, fēowertiġ のように,半子音 ġ で終わっていた.これらの基数詞を序数詞にするには,つなぎ母音を頭にもつ接尾辞の異形態 -oða, -oðe を付加し,twēntiġoða, þrītiġoða, fēowertiġoða のようにした.基数詞においては,後にこの半子音は先行する母音 /i/ に吸収されて消失したが,序数詞においては,この半子音と接尾辞のつなぎ母音の連鎖が曖昧母音 /ə/ として生き残ったものと考えられる.つまり,twentieth のやや不規則な綴字と発音は,歴史的には,10の倍数を表わす基数詞が,語尾にある種の子音的な ġ を保持していたことに部分的に起因するといえる.

しかし,実際の歴史的発展は,古英語から現代英語にかけて上の説明にあるように直線的だったわけではないようだ.というのは,古英語でもつなぎ母音のない twentigþa のような綴字はあったし,中英語では twentiþe, twentythe などの素直な綴字も普通にみられたからだ (cf. MED twentīeth (num.)) .むしろ,現在の形態は,16世紀になってから顕著になってきた.例えば,Shakespeare では,Quarto 版では twentith,1st Folio 版では twentieth (MV 4.1.329, Ham 3.4.97) と綴られており,通時的変化を示唆している.おそらくは,時代によって,方言によって,つなぎ母音の有無はしばしば交替したと思われ,初期近代英語期における語形の標準化の流れのなかで,つなぎ母音のある形態が選択されたということなのではないか.

以下,参考までに OED による序数詞接尾辞 -th, suffix2 の解説を貼りつけておく.

Forming ordinal numbers; in modern literary English used with all simple numbers from fourth onward; representing Old English -þa, -þe, or -oða, -oðe, used with all ordinals except fífta, sixta, ellefta, twelfta, which had the ending -ta, -te; in Sc., north. English, and many midland dialects the latter, in form -t, is used with all simple numerals after third (fourt, fift, sixt, sevent, tent, hundert, etc.). In Kentish and Old Northumbrian those from seventh to tenth had formerly the ending -da, -de. All these variations, -th, -t, -d, represent an original Indo-European -tos (cf. Greek πέμπ-τος, Latin quin-tus), understood to be identical with one of the suffixes of the superlative degree. In Old English fífta, sixta, the original t was retained, being protected by the preceding consonant; the -þa and -da were due to the position of the stress accent, according to Verner's Law. The ordinals from twentieth to ninetieth have -eth, Old English -oða, -oðe. In compound numerals -th is added only to the last, as 1/1345, the one thousand three hundred and forty-fifth part; in his one-and-twentieth year.[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2015-05-06 Wed

■ #2200. なぜ *haves, *haved ではなく has, had なのか [phonetics][consonant][assimilation][conjugation][inflection][3sp][verb][paradigm][oe][suffix][sobokunagimon][have][v]

標記のように,現代英語の have は不規則変化動詞である.しかし,has に -s があるし, had に -d もあるから,完全に不規則というよりは若干不規則という程度だ.だが,なぜ *haves や *haved ではないのだろうか.

歴史的にみれば,現在では許容されない形態 haves や haved は存在した.古英語形態論に照らしてみると,この動詞は純粋に規則的な屈折をする動詞ではなかったが,相当程度に規則的であり,当面は事実上の規則変化動詞と考えておいて差し支えない.古英語や,とりわけ中英語では,haves や haved に相当する「規則的」な諸形態が確かに行われていたのである.

古英語 habban (have) の屈折表は,「#74. /b/ と /v/ も間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-11-1]) で掲げたが,以下に異形態を含めた表を改めて掲げよう.

| habban (have) | Present Indicative | Present Subjunctive | Preterite Indicative | Preterite Subjunctive | Imperative |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st sg. | hæbbe | hæbbe | hæfde | hæfde | |

| 2nd sg. | hæfst, hafast | hafa | |||

| 3rd sg. | hæfþ, hafaþ | ||||

| pl. | habbaþ | hæbben | hæfdon | hæfden | habbaþ |

Pres. Ind. 3rd Sg. の箇所をみると,古英語で has に相当する形態として,hæfþ, hafaþ の2系列があったことがわかる.fþ のように2子音が隣接する前者の系列では,中英語期に最初の子音 f が脱落し,hath などの形態を生んだ.この hath は近代英語期まで続いた.

3単現の語尾が -(e)th から -(e)s へ変化した経緯について「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) を始め,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化」 ([2015-03-23-1]) などの記事で取り上げてきたが,目下の関心である現代英語の has という形態の直接の起源は,hath の屈折語尾の置換に求めるよりは,古英語の Northumbria 方言に確認される hæfis, haefes などに求めるべきだろう.この -s 語尾をもつ古英語の諸形態は,中英語期にはさらに多くの形態を発達させたが,f が母音に挟まれた環境で脱落したり,fs のように2子音が隣接する環境で脱落するなどして,結果的に has のような形態が出力された.hath と has から唇歯音が脱落した過程は,このようにほぼ平行的に説明できる.関連して,have と of について,後続語が子音で始まるときに唇歯音が脱落することが後期中英語においてみられた.ye ha seyn (you have seen) や o þat light (of that light) などの例を参照されたい (中尾,p. 411).

なお,過去形 had についてだが,こちらは「#1348. 13世紀以降に生じた v 削除」 ([2013-01-04-1]) で取り上げたように,多くの語に生じた v 削除の出力として説明できる.「#23. "Good evening, ladies and gentlemen!"は間違い?」 ([2009-05-21-1]) も合わせて参照されたい.

MED の hāven (v.) の壮観な異綴字リストで,has や had に相当する諸形態を確かめてもらいたい.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2015-04-24 Fri

■ #2188. spinster, youngster などにみられる接尾辞 -ster [suffix][affixation][word_formation][oe][etymology][gender]

古英語の -estre, -istre (< Gmc *-strjōn) は女性の行為者名詞を作る接尾辞 (agentive suffix) で,男性の行為者名詞を作る -ere に対立していた.西ゲルマン語群に散発的に見られる接尾辞で,MLG -(e)ster, (M)D and ModFrisian -ster が同根だが,HG, OS, OFrisian には文証されない.古英語からの語例としては hlēapestre (female dancer), hoppestre (female dancer), lǣrestre (female teacher), lybbestre (female poisoner, witch), miltestre (harlot), sangestre (songstress), sēamstre (seamstress, sempstress), webbestre (female weaver) などがある.この造語法にのっとり,中英語期にも spinnestre (spinster) などが作られている.しかし,中英語以降,まず北部方言で,さらに16世紀までには南部方言でも,女性に限らず一般的に行為者名詞を作る接尾辞として発達した.例えば,1300年以前に北部方言で書かれた Cursor Mundi では,demere ではなく demestre が性別に関係なく判事 (judge) の意味で用いられた.近代期には seamster や songster 単独では男女の区別がつかなくなり,区別をつけるべく新しく女性接尾辞 -ess を加えた seamstress や songstress が作られた.

-ster は,単なる動作主名詞を作る -er に対して,軽蔑的な含意をもって職業や習性を表わす傾向がある (ex. fraudster, gamester, gangster, jokester, mobster, punster, rhymester, speedster, slickster, tapster, teamster, tipster, trickster) .この軽蔑的な響きは,ラテン語由来ではあるが形態的に類似した行為者名詞を作る接尾辞 -aster のネガティヴな含意からの影響が考えられる (cf. criticaster, poetaster) .-ster を形容詞に付加した例としては,oldster, youngster がある.職業名であるから固有名詞となったものもあり,上記 Webster のほか,Baxter (baker) などもみられる.

ほかにも多くの -ster 語があるが,女性名詞を作るという古英語の伝統を今に伝えるのは,spinster のみとなってしまった.この語については,別の観点から「#1908. 女性を表わす語の意味の悪化 (1)」 ([2014-07-18-1]),「#1968. 語の意味の成分分析」 ([2014-09-16-1]) で触れたので,そちらも参照されたい.

2015-03-23 Mon

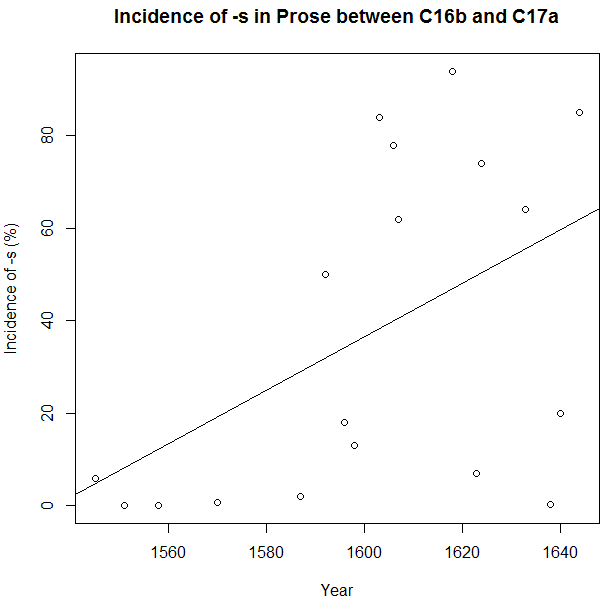

■ #2156. C16b--C17a の3単現の -th → -s の変化 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][lexical_diffusion][schedule_of_language_change][speed_of_change][bible]

初期近代英語における動詞現在人称語尾 -th → -s の変化については,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]),「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]),「#2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要」 ([2015-03-08-1]) などで取り上げてきた.今回,この問題に関連して Bambas の論文を読んだ.現在の最新の研究成果を反映しているわけではないかもしれないが,要点が非常によくまとまっている.

英語史では,1600年辺りの状況として The Authorised Version で不自然にも3単現の -s が皆無であることがしばしば話題にされる.Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) にも -s が見当たらないことが知られている.ここから,当時,文学的散文では -s は口語的にすぎるとして避けられるのが普通だったのではないかという推測が立つ.現に Jespersen (19) はそのような意見である.

Contemporary prose, at any rate in its higher forms, has generally -th'; the s-ending is not at all found in the A[uthorized] V[ersion], nor in Bacon A[tlantis] (though in Bacon E[ssays] there are some s'es). The conclusion with regard to Elizabethan usage as a whole seems to be that the form in s was a colloquialism and as such was allowed in poetry and especially in the drama. This s must, however, be considered a licence wherever it occurs in the higher literature of that period. (qtd in Bambas, p. 183)

しかし,Bambas (183) によれば,エリザベス朝の散文作家のテキストを広く調査してみると,実際には1590年代までには文学的散文においても -s は容認されており,忌避されている様子はない.その後も,個人によって程度の違いは大きいものの,-s が避けられたと考える理由はないという.Jespersen の見解は,-s の過小評価であると.

The fact seems to be that by the 1590's the -s-form was fully acceptable in literary prose usage, and the varying frequency of the occurrence of the new form was thereafter a matter of the individual writer's whim or habit rather than of deliberate selection.

さて,17世紀に入ると -th は -s に取って代わられて稀になっていったと言われる.Wyld (333--34) 曰く,

From the beginning of the seventeenth century the 3rd Singular Present nearly always ends in -s in all kinds of prose writing except in the stateliest and most lofty. Evidently the translators of the Authorized Version of the Bible regarded -s as belonging only to familiar speech, but the exclusive use of -eth here, and in every edition of the Prayer Book, may be partly due to the tradition set by the earlier biblical translations and the early editions of the Prayer Book respectively. Except in liturgical prose, then, -eth becomes more and more uncommon after the beginning of the seventeenth century; it is the survival of this and not the recurrence of -s which is henceforth noteworthy. (qtd in Bambas, p. 185)

だが,Bambas はこれにも異議を唱える.Wyld の見解は,-eth の過小評価であると.つまるところ Bambas は,1600年を挟んだ数十年の間,-s と -th は全般的には前者が後者を置換するという流れではあるが,両者並存の時代とみるのが適切であるという意見だ.この意見を支えるのは,Bambas 自身が行った16世紀半ばから17世紀半ばにかけての散文による調査結果である.Bambas (186) の表を再現しよう.

| Author | Title | Date | Incidence of -s |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ascham, Roger | Toxophilus | 1545 | 6% |

| Robynson, Ralph | More's Utopia | 1551 | 0% |

| Knox, John | The First Blast of the Trumpet | 1558 | 0% |

| Ascham, Roger | The Scholmaster | 1570 | 0.7% |

| Underdowne, Thomas | Heriodorus's Anaethiopean Historie | 1587 | 2% |

| Greene, Robert | Groats-Worth of Witte; Repentance of Robert Greene; Blacke Bookes Messenger | 1592 | 50% |

| Nashe, Thomas | Pierce Penilesse | 1592 | 50% |

| Spenser, Edmund | A Veue of the Present State of Ireland | 1596 | 18% |

| Meres, Francis | Poetric | 1598 | 13% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Wonderfull Yeare 1603 | 1603 | 84% |

| Dekker, Thomas | The Seuen Deadlie Sinns of London | 1606 | 78% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Defence of Ryme | 1607 | 62% |

| Daniel, Samuel | The Collection of the History of England | 1612--18 | 94% |

| Drummond of Hawlhornden, W. | A Cypress Grove | 1623 | 7% |

| Donne, John | Devotions | 1624 | 74% |

| Donne, John | Ivvenilia | 1633 | 64% |

| Fuller, Thomas | A Historie of the Holy Warre | 1638 | 0.4% |

| Jonson, Ben | The English Grammar | 1640 | 20% |

| Milton, John | Areopagitica | 1644 | 85% |

これをプロットすると,以下の通りになる.

この期間では年間0.5789%の率で上昇していることになる.相関係数は0.49である.全体としては右肩上がりに違いないが,個々のばらつきは相当にある.このことを過小評価も過大評価もすべきではない,というのが Bambas の結論だろう.

・ Bambas, Rudolph C. "Verb Forms in -s and -th in Early Modern English Prose". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46 (1947): 183--87.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

・ Wyld, Henry Cecil. A History of Modern Colloquial English. 2nd ed. London: Fisher Unwin, 1921.

2015-03-08 Sun

■ #2141. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の概要 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][suffix][inflection][3sp][bible][shakespeare][schedule_of_language_change]

「#1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力」 ([2014-05-28-1]) でみたように,17世紀中に3単現の屈折語尾が -th から -s へと置き換わっていった.今回は,その前の時代から進行していた置換の経緯を少し紹介しよう.

古英語後期より北部方言で行なわれていた3単現の -s を別にすれば,中英語の南部で -s が初めて現われたのは14世紀のロンドンのテキストにおいてである.しかし,当時はまだ稀だった.15世紀中に徐々に頻度を増したが,爆発的に増えたのは16--17世紀にかけてである.とりわけ口語を反映しているようなテキストにおいて,生起頻度が高まっていったようだ.-s は,およそ1600年までに標準となっていたと思われるが,16世紀のテキストには相当の揺れがみられるのも事実である.古い -th は母音を伴って -eth として音節を構成したが,-s は音節を構成しなかったため,両者は韻律上の目的で使い分けられた形跡がある (ex. that hateth thee and hates us all) .例えば,Shakespeare では散文ではほとんど -s が用いられているが,韻文では -th も生起する.とはいえ,両形の相対頻度は,韻律的要因や文体的要因以上に個人または作品の性格に依存することも多く,一概に論じることはできない.ただし,doth や hath など頻度の非常に高い語について,古形がしばらく優勢であり続け,-s 化が大幅に遅れたということは,全体的な特徴の1つとして銘記したい.

Lass (162--65) は,置換のスケジュールについて次のように要約している.

In the earlier sixteenth century {-s} was probably informal, and {-th} neutral and/or elevated; by the 1580s {-s} was most likely the spoken norm, with {-eth} a metrical variant.

宇賀治 (217--18) により作家や作品別に見てみると,The Authorised Version (1611) や Bacon の The New Atlantis (1627) には -s が見当たらないが,反対に Milton (1608--74) では doth と hath を別にすれば -th が見当たらない.Shakespeare では,Julius Caesar (1599) の分布に限ってみると,-s の生起比率が do と have ではそれぞれ 11.76%, 8.11% だが,それ以外の一般の動詞では 95.65% と圧倒している.

とりわけ16--17世紀の証拠に基づいた議論において注意すべきは,「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) で見たように,表記上 -th とあったとしても,それがすでに [s] と発音されていた可能性があるということである.

置換のスケジュールについては,「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 3. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

・ 宇賀治 正朋 『英語史』 開拓社,2000年.

2015-02-12 Thu

■ #2117. playwright [etymology][metathesis][verb][suffix]

英語の姓に Wright さんは普通にみられるが,これは「職人」の意味である.普通名詞として単体で wright (職人)として用いられることは今はほとんどないが,様々な種類の職人を表すのに複合語の一部として用いられることはある.比較的よくみるのは playwright (劇作家)である.これは戯曲を書く (write) 人ではなく,職人的に作り出す人 (wright) である.もし write (書く)に関係しているのであれば,行為者を表す接尾辞 (agentive suffix) をつけて writer (書き手)となるはずだろう.ほかにも arkwright, boatwright, cartwright, comedywright, housewright, millwright, novelwright, ploughwright, shipwright, timberwright, waggonwright, wainwright, wheelwright, woodwright などがある.

この wright は起源を遡ると,動詞 work に関係する.この動詞の古英語形 wyrcan は「行う;作る;生み出す」など広い意味で用いられ,その語幹に語尾が付加された wyrhta (< wyrcta) が「職人」として使われた.この語形成は他のゲルマン諸語にも見られ,起源は相応して古いものと思われる.wyrhta からは,第1母音と r とが音位転換 (metathesis) した wryhta が異形として生まれ,後に <a> で表される語末母音が水平化・消失するに及んで,現代につらなる wright の母型ができあがった.音位転換は,work の古い過去・過去分詞形 wrought にも見られる.

MED の wrigt(e (n.(1)) によると,中英語で,この語が以下のようなあまたの綴字(そしておそらくは発音)で実現されていたことがうかがえる.

wright(e (n.(1)) Also wrigt(e, wrigth(e, wrigh, wriȝt(e, wriȝth(e, wriht(e, writ(e, writh(e, writht, wreth(e, (N) wreght, (SWM) wrouhte, whrouhte & (chiefly early) wricht(e, (early) wirhte, (chiefly SW or SWM) wruhte, wruchte, wurhte, wurhta, wurhtæ, wuruhte & (in names) wrightte, wrighthe, wrig, wri(h)tte, wrihgte, wrichgte, wrich(e, wrict(e, wricth(e, wrick, wristh, wrieth, wreghte, wreȝte, wrehte, wrechte, wrecthe, wreit, wreitche, wreut(t)e, wroghte, wrozte, wrouȝte, wrughte, wrushte, wrh(i)te, wirgh, wirchte, wiche, wergh(t)e, werhte, wereste, worght(t)e, worichte, worithte, wort, worth, whrighte, whrit, whreihte, whergte, right, rith; pl. wrightes, etc. & wriȝttis, writtis, (NEM) whrightes & (early) wrihten, wirhten, (SWM) wrohtes, wurhten, (early gen.) wurhtena, (early dat.) wurhtan & (gen. in place names) wrightin(g)-, wri(c)tin-, wrichting-, wrstinc-, uritting-.

また,中英語では castlewright, feltwright, glasswright などに相当する現代には見られない職人名や,battlewright (戦士),Latinwright (ラテン語学者)などに相当する変わり種も見られた.複合語の人名も,現代まで伝わっているものもいくつかあるが, Basketwricte, Bordwricht, Bowwrighth, Briggwricht, Cartewrychgte, Chesewricte, Waynwryche, Wycchewrichte など幅広く存在した.

中英語までは wright は複合語要素として生産性を保っていたようだが,その後は次第に衰えていき,現在では数えるほどしか残っていない.この衰退の原因として,中英語以降にフランス語やラテン語から新たな職業・職人名詞が流入してきたこと,-er や -ist を含む種々の行為者接尾辞による語形成が活発化してきたことが疑われるが,未調査である.

2015-01-04 Sun

■ #2078. young + -th = youth? [suffix][phonetics][cognate][consonant]

抽象名詞を作る接尾辞 -th については「#14. 抽象名詞の接尾辞-th」 ([2009-05-12-1]),「#16. 接尾辞-th をもつ抽象名詞のもとになった動詞・形容詞は?」 ([2009-05-14-1]),「#595. death and dead」 ([2010-12-13-1]),「#1787. coolth」 ([2014-03-19-1]) で取り上げてきた.音韻変化や類推などの複雑な経緯により,基体と -th を付した派生語との関係が発音や綴字の上では見えにくくなっているものも多いが,そのような例の1つに young -- youth のペアがある.long -- length, strong -- strength では,語幹末の ng が保たれているのに,young の名詞形では鼻音が落ちて youth となるのは何故か.

古英語では基体となる形容詞は geong,派生名詞は geoguþ であり,後者ではすでに鼻音が脱落している.ゲルマン諸語での同根語をみてみると,Old Saxon juguð, Dutch jeugd, Old High German jugund, German jugend と鼻音の有無で揺れているが,低地ゲルマン諸語で名詞形の鼻音が落ちているようだ.西ゲルマン祖語では *jugunþi と n が再建されている(ラテン語 juvenis (adj.), juventa (n.) も参照).Partridge によると,"OE geong has derivative geoguth or geogoth---a collective n---prob an easing of *geonth" とあり,発音の便のために問題の鼻音が落ちたということらしい.詳しくは未調査だが,印欧祖語の段階より young の語幹末の振る舞いは long や strong のそれとは異なるものだったようだ.なお,14世紀初頭には形容詞 young からの素直な類推による youngth に相当する形態も行われている.

ちなみに OED によると,古英語 geoguþ は,動詞 dugan (to be good or worth) の名詞形 duguþ (worth, virtue, excellence, nobility, manhood, force, a force, an army, people) とゲルマン語の段階で類推関係にあった可能性があるという.古英語 duguþ は中英語へは douth として伝わったが,1400年頃を最終例として廃用となった.

・ Partridge, Eric Honeywood. Origins: A Short Etymological Dictionary of Modern English. 4th ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966. 1st ed. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; New York: Macmillan, 1958.

2014-11-19 Wed

■ #2032. 形容詞語尾 -ive [etymology][suffix][french][loan_word][spelling][pronunciation][verners_law][consonant][stress][gsr][adjective]

フランス語を学習中の学生から,こんな質問を受けた.フランス語では actif, effectif など語尾に -if をもつ語(本来的に形容詞)が数多くあり,男性形では見出し語のとおり -if を示すが,女性形では -ive を示す.しかし,これらの語をフランス語から借用した英語では -ive が原則である.なぜ英語はフランス語からこれらの語を女性形で借用したのだろうか.

結論からいえば,この -ive はフランス語の対応する女性形語尾 -ive を直接に反映したものではない.英語は主として中英語期にフランス語からあくまで見出し語形(男性形)の -if の形で借用したのであり,後に英語内部での音声変化により無声の [f] が [v] へ有声化し,その発音に合わせて -<ive> という綴字が一般化したということである.

中英語ではこれらのフランス借用語に対する優勢な綴字は -<if> である.すでに有声化した -<ive> も決して少なくなく,個々の単語によって両者の間での揺れ方も異なると思われるが,基本的には -<if> が主流であると考えられる.試しに「#1178. MED Spelling Search」 ([2012-07-18-1]) で,"if\b.*adj\." そして "ive\b.*adj\." などと見出し語検索をかけてみると,数としては -<if> が勝っている.現代英語で頻度の高い effective, positive, active, extensive, attractive, relative, massive, negative, alternative, conservative で調べてみると,MED では -<if> が見出し語として最初に挙がっている.

しかし,すでに後期中英語にはこの綴字で表わされる接尾辞の発音 [ɪf] において,子音 [f] は [v] へ有声化しつつあった.ここには強勢位置の問題が関与する.まずフランス語では問題の接尾辞そのもに強勢が落ちており,英語でも借用当初は同様に接尾辞に強勢があった.ところが,英語では強勢位置が語幹へ移動する傾向があった (cf. 「#200. アクセントの位置の戦い --- ゲルマン系かロマンス系か」 ([2009-11-13-1]),「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1]),「#861. 現代英語の語強勢の位置に関する3種類の類推基盤」 ([2011-09-05-1]),「#1473. Germanic Stress Rule」 ([2013-05-09-1])) .接尾辞に強勢が落ちなくなると,末尾の [f] は Verner's Law (の一般化ヴァージョン)に従い,有声化して [v] となった.verners_law と子音の有声化については,特に「#104. hundred とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2009-08-09-1]) と「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) を参照されたい.

上記の音韻環境において [f] を含む摩擦音に有声化が生じたのは,中尾 (378) によれば,「14世紀後半から(Nではこれよりやや早く)」とある.およそ同時期に,[s] > [z], [θ] > [ð] の有声化も起こった (ex. is, was, has, washes; with) .

上に述べた経緯で,フランス借用語の -if は後に軒並み -ive へと変化したのだが,一部例外的に -if にとどまったものがある.bailiff (執行吏), caitiff (卑怯者), mastiff (マスチフ), plaintiff (原告)などだ.これらは,古くは [f] と [v] の間で揺れを示していたが,最終的に [f] の音形で標準化した少数の例である.

以上を,Jespersen (200--01) に要約してもらおう.

The F ending -if was in ME -if, but is in Mod -ive: active, captive, etc. Caxton still has pensyf, etc. The sound-change was here aided by the F fem. in -ive and by the Latin form, but these could not prevail after a strong vowel: brief. The law-term plaintiff has kept /f/, while the ordinary adj. has become plaintive. The earlier forms in -ive of bailiff, caitif, and mastiff, have now disappeared.

冒頭の質問に改めて答えれば,英語 -ive は直接フランス語の(あるいはラテン語に由来する)女性形接尾辞 -ive を借りたものではなく,フランス語から借用した男性形接尾辞 -if の子音が英語内部の音韻変化により有声化したものを表わす.当時の英語話者がフランス語の女性形接尾辞 -ive にある程度見慣れていたことの影響も幾分かはあるかもしれないが,あくまでその関与は間接的とみなしておくのが妥当だろう.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

2014-10-08 Wed

■ #1990. 様々な種類の意味 [semantics][pragmatics][derivation][inflection][word_formation][idiom][suffix]

「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で触れたが,Stern は様々な種類の意味を区別している.いずれも2項対立でわかりやすく,後の意味論に基礎的な視点を提供したものとして評価できる.そのなかでも論理的な基準によるとされる種々の意味の区別を下に要約しよう (Stern 68--87) .

(1) actual vs lexical meaning. 前者は実際の発話のなかに生じる語の意味を,後者は語(や句)が文脈から独立した状態で単体としてもつ意味をさす.後者は辞書的な意味ともいえるだろう.文法書に例文としてあげられる文の意味も,文脈から独立しているという点で,lexical meaning に類する.通常,意味は実際の発話のなかにおいて現われるものであり,単体で現われるのは上記のように辞書や文法書など語学に関する場面をおいてほかにない.actual meaning は定性 (definiteness) をもつが,lexical meaning は不定 (indefinite) である.

(2) general vs particular meaning. 例えば The dog is a domestic animal. の主語は集合的・総称的な意味をもつが,That dog is mad. の主語は個別の意味をもつ.すべての名前は,このように種を表わす総称的な用法と個体を表わす個別的な用法をもつ.名詞とは若干性質は異なるが,形容詞や動詞にも同種の区別がある.

(3) specialised vs referential meaning. ある語の指示対象がいくつかの性質を有するとき,話者はそれらの性質の1つあるいはいくつかに焦点を当てながらその語を用いることがある.例えば He was a man, take him for all in all. という文において man は,ある種の道徳的な性質をもっているものとして理解されている.このような指示の仕方がなされるとき,用いられている語は specialised meaning を有しているとみなされる.一方,He had an army of ten thousand men. というときの men は,各々の個性がかき消されており,あくまで指示的な意味 (referential meaning) を有するにすぎない.厳密には,referential meaning は specialised meaning と対立するというよりは,その特殊な現われ方の1つととらえるべきだろう.前項の particular meaning と 本項の specialised meaning は混同しやすいが,particular meaning は語の指示対象の範囲の限定として,specialised meaning は語の意味範囲の限定としてとらえることができる.

(4) tied vs contingent meaning. 前者は語と言語的文脈により指示対象が決定する場合の意味であり,後者はそれだけでは指示対象が決定せず話者やその他の状況をも考慮に入れなければならない場合の意味である.前者は意味論的な意味,後者は語用論的な意味といってもよい.

(5) basic vs relational meaning. 語が「語幹+接尾辞」から成っている場合,語幹の意味は basic,接尾辞の意味は relational といわれる.例えば,ラテン語 lupi は,狼という基本的意味を有する語幹 lup- と単数属格という統語関係的意味 (syntactical relational meaning) を有する接尾辞 -i からなる.統語関係的意味は接尾辞によって表わされるとは限らず,語幹の母音交替 ( Ablaut or gradation ) によって表わされたり (ex. ring -- rang -- rung) ,語順によって表わされたり (ex. Jack beats Jill. vs Jill beats Jack.) もすれば,何によっても表わされないこともある.一方,派生関係的意味 (derivational relational meaning) は,例えば like -- liken -- likeness のシリーズにみられるような -en や -ness 接尾辞によって表わされている.大雑把にいって,統語関係的意味と派生関係的意味は,それぞれ屈折接辞と派生接辞に対応すると考えることができる.

(6) word- vs phrase-meaning. あらゆる種類の慣用句 (idiom) や慣用的な文 (ex. How do you do?) を思い浮かべればわかるように,句の意味は,しばしばそれを構成する複数の単語の意味の和にはならない.

(7) autosemantic vs synsemantic meaning. 聞き手にイメージを喚起させる意図で発せられる表現(典型的には文や名前)は,autosemantic meaning をもつといわれる.一方,前置詞,接続詞,形容詞,ある種の動詞の形態 (ex. goes, stands, be, doing) ,従属節,斜格の名詞,複合語の各要素は synsemantic meaning をもつといわれる.

・ Stern, Gustaf. Meaning and Change of Meaning. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 1931.

2014-10-01 Wed

■ #1983. -ick or -ic (3) [suffix][corpus][spelling][emode][eebo][johnson]

昨日の記事「#1982. -ick or -ic (2)」 ([2014-09-30-1]) に引き続き,初期近代英語での -ic(k) 語の異綴りの分布(推移)を調査する.使用するコーパスは市販のものではなく,個人的に EEBO (Early English Books Online) からダウンロードして蓄積した巨大テキスト集である.まだコーパス風に整備しておらず,代表性も均衡も保たれていない単なるテキストの集合という体なので,調査結果は仮のものとして解釈しておきたい.時代区分は16世紀と17世紀に大雑把に分け,それぞれコーパスサイズは923,115語,9,637,954語である(コーパスサイズに10倍以上の開きがある不均衡な実態に注意).以下では,100万語当たりの頻度 (wpm) で示してある.

| Spelling pair | Period 1 (1501--1600) (in wpm) | Period 2 (1601--1700) (in wpm) |

|---|---|---|

| angelick / angelic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.21 |

| antick / antic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.49 / 0.10 |

| apoplectick / apoplectic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| aquatick / aquatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arabick / arabic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| archbishoprick / archbishopric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| arctick / arctic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| arithmetick / arithmetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.22 / 0.31 |

| aromatick / aromatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| asiatick / asiatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| attick / attic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.21 |

| authentick / authentic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.42 |

| balsamick / balsamic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| baltick / baltic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| bishoprick / bishopric | 1.08 / 0.00 | 4.25 / 0.00 |

| bombastick / bombastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| catholick / catholic | 5.42 / 0.00 | 38.39 / 1.97 |

| caustick / caustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| characteristick / characteristic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| cholick / cholic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| comick / comic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| critick / critic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.76 / 1.87 |

| despotick / despotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.21 |

| domestick / domestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.09 / 0.21 |

| dominick / dominic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 0.62 / 0.42 |

| dramatick / dramatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.10 |

| emetick / emetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| epick / epic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.10 |

| ethick / ethic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.10 |

| exotick / exotic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.73 / 0.10 |

| fabrick / fabric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 8.72 / 0.31 |

| fantastick / fantastic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.42 / 0.10 |

| frantick / frantic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.94 / 0.00 |

| frolick / frolic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.00 |

| gallick / gallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.52 |

| garlick / garlic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 2.28 / 0.00 |

| heretick / heretic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 6.02 / 0.00 |

| heroick / heroic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 16.91 / 1.35 |

| hieroglyphick / hieroglyphic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.00 |

| lethargick / lethargic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.10 |

| logick / logic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 7.06 / 1.04 |

| lunatick / lunatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| lyrick / lyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.10 |

| magick / magic | 2.17 / 0.00 | 3.32 / 0.10 |

| majestick / majestic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.88 / 0.42 |

| mechanick / mechanic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.15 / 0.00 |

| metallick / metallic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| metaphysick / metaphysic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.21 |

| mimick / mimic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.42 / 0.00 |

| musick / music | 7.58 / 627.22 | 40.98 / 251.40 |

| mystick / mystic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.10 |

| panegyrick / panegyric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 4.46 / 0.10 |

| panick / panic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.35 / 0.10 |

| paralytick / paralytic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.00 |

| pedantick / pedantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| philosophick / philosophic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.00 / 0.21 |

| physick / physic | 1.08 / 0.00 | 27.39 / 1.56 |

| plastick / plastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| platonick / platonic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| politick / politic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 15.98 / 1.14 |

| prognostick / prognostic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| publick / public | 5.42 / 3.25 | 237.39 / 5.71 |

| relick / relic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.52 / 0.00 |

| republick / republic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 3.01 / 0.31 |

| rhetorick / rhetoric | 0.00 / 0.00 | 5.71 / 0.21 |

| rheumatick / rheumatic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| romantick / romantic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.83 / 0.00 |

| rustick / rustic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.66 / 0.00 |

| sceptick / sceptic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.10 / 0.10 |

| scholastick / scholastic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.31 / 0.42 |

| stoick / stoic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.93 / 0.00 |

| sympathetick / sympathetic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 0.21 / 0.00 |

| topick / topic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.45 / 0.00 |

| traffick / traffic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 8.61 / 0.42 |

| tragick / tragic | 3.25 / 0.00 | 2.91 / 0.00 |

| tropick / tropic | 0.00 / 0.00 | 1.04 / 0.00 |

全体として眺めると,初期近代英語では -ick のほうが -ic よりも優勢である.-ic が例外的に優勢なのは,16世紀からの music と,17世紀の critic, scholastic くらいである.昨日の結果と合わせて推測すると,1700年以降,おそらく18世紀前半の間に,-ick から -ic への形勢の逆転が比較的急速に進行していたのではないか.個々の語において逆転のスピードは多少異なるようだが,一般的な傾向はつかむことができた.18世紀半ばに -ick を選んだ Johnson は,やはり保守的だったようだ.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2014-09-30 Tue

■ #1982. -ick or -ic (2) [suffix][johnson][webster][corpus][spelling][clmet][lmode]

「#872. -ick or -ic」 ([2011-09-16-1]) の記事で,<public> と <publick> の綴字の分布の通時的変化について,Google Books Ngram Viewer と Google Books: American English を用いて簡易調査した.-ic と -ick の歴史上の変異については,Johnson の A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) では前者が好まれていたが,Webster の The American Dictionary of the English Language (1828) では後者へと舵を切っていたと一般論を述べた.しかし,この一般論は少々訂正が必要のようだ.

「#1637. CLMET3.0 で between と betwixt の分布を調査」 ([2013-10-20-1]) で紹介した CLMET3.0 を用いて,後期近代英語の主たる -ic(k) 語の綴字を調査してみた.1710--1920年の期間を3期に分けて,それぞれの綴字で頻度をとっただけだが,結果を以下に掲げよう.

| Spelling pair | Period 1 (1710--1780) | Period 2 (1780--1850) | Period 3 (1850--1920) |

|---|---|---|---|

| angelick / angelic | 6 / 50 | 0 / 68 | 0 / 50 |

| antick / antic | 4 / 10 | 1 / 6 | 0 / 3 |

| apoplectick / apoplectic | 0 / 10 | 1 / 19 | 0 / 14 |

| aquatick / aquatic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 35 | 0 / 56 |

| arabick / arabic | 2 / 101 | 0 / 45 | 0 / 115 |

| archbishoprick / archbishopric | 4 / 7 | 2 / 2 | 0 / 8 |

| arctick / arctic | 1 / 5 | 0 / 20 | 0 / 93 |

| arithmetick / arithmetic | 9 / 32 | 0 / 77 | 0 / 98 |

| aromatick / aromatic | 4 / 14 | 0 / 29 | 0 / 36 |

| asiatick / asiatic | 1 / 101 | 0 / 48 | 0 / 76 |

| attick / attic | 1 / 32 | 0 / 34 | 0 / 71 |

| authentick / authentic | 4 / 160 | 0 / 79 | 0 / 68 |

| balsamick / balsamic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 5 | 0 / 1 |

| baltick / baltic | 4 / 50 | 0 / 33 | 0 / 43 |

| bishoprick / bishopric | 3 / 28 | 2 / 9 | 0 / 19 |

| bombastick / bombastic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 4 |

| cathartick / cathartic | 0 / 1 | 1 / 0 | 0 / 0 |

| catholick / catholic | 7 / 291 | 0 / 342 | 0 / 296 |

| caustick / caustic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 20 |

| characteristick / characteristic | 8 / 92 | 0 / 354 | 0 / 687 |

| cholick / cholic | 1 / 13 | 0 / 2 | 0 / 1 |

| comick / comic | 1 / 68 | 0 / 67 | 0 / 165 |

| coptick / coptic | 1 / 11 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 35 |

| critick / critic | 12 / 153 | 0 / 168 | 0 / 155 |

| despotick / despotic | 9 / 66 | 0 / 51 | 0 / 65 |

| dialectick / dialectic | 1 / 0 | 0 / 0 | 0 / 6 |

| didactick / didactic | 0 / 10 | 1 / 20 | 0 / 23 |

| domestick / domestic | 46 / 733 | 0 / 736 | 0 / 488 |

| dominick / dominic | 4 / 11 | 0 / 14 | 1 / 3 |

| dramatick / dramatic | 8 / 214 | 0 / 206 | 0 / 216 |

| elliptick / elliptic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 8 | 0 / 2 |

| emetick / emetic | 4 / 5 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 5 |

| epick / epic | 1 / 68 | 0 / 83 | 1 / 38 |

| ethick / ethic | 1 / 6 | 0 / 0 | 0 / 3 |

| exotick / exotic | 2 / 7 | 0 / 20 | 0 / 38 |

| fabrick / fabric | 15 / 116 | 1 / 84 | 0 / 111 |

| fantastick / fantastic | 9 / 45 | 0 / 157 | 0 / 198 |

| frantick / frantic | 5 / 88 | 2 / 163 | 0 / 124 |

| frolick / frolic | 19 / 44 | 0 / 46 | 0 / 32 |

| gaelick / gaelic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 30 | 0 / 64 |

| gallick / gallic | 1 / 75 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 10 |

| gothick / gothic | 2 / 498 | 0 / 131 | 0 / 66 |

| heretick / heretic | 2 / 31 | 0 / 37 | 0 / 24 |

| heroick / heroic | 17 / 201 | 2 / 224 | 0 / 211 |

| hieroglyphick / hieroglyphic | 2 / 4 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 8 |

| hysterick / hysteric | 1 / 9 | 0 / 10 | 0 / 6 |

| laconick / laconic | 2 / 13 | 0 / 14 | 0 / 7 |

| lethargick / lethargic | 1 / 12 | 0 / 8 | 0 / 14 |

| logick / logic | 4 / 62 | 0 / 361 | 0 / 367 |

| lunatick / lunatic | 2 / 32 | 0 / 34 | 0 / 77 |

| lyrick / lyric | 3 / 15 | 0 / 26 | 0 / 37 |

| magick / magic | 9 / 110 | 0 / 296 | 0 / 292 |

| majestick / majestic | 4 / 73 | 0 / 149 | 1 / 115 |

| mechanick / mechanic | 6 / 79 | 0 / 47 | 0 / 58 |

| metallick / metallic | 1 / 9 | 0 / 79 | 0 / 137 |

| metaphysick / metaphysic | 1 / 2 | 0 / 11 | 0 / 9 |

| mimick / mimic | 2 / 25 | 1 / 46 | 0 / 23 |

| musick / music | 87 / 549 | 3 / 1220 | 3 / 1684 |

| mystick / mystic | 1 / 39 | 0 / 92 | 0 / 167 |

| obstetrick / obstetric | 1 / 2 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 0 |

| panegyrick / panegyric | 19 / 121 | 0 / 43 | 0 / 16 |

| panick / panic | 14 / 58 | 1 / 90 | 0 / 314 |

| paralytick / paralytic | 1 / 15 | 0 / 41 | 0 / 14 |

| pedantick / pedantic | 3 / 31 | 0 / 28 | 0 / 29 |

| philippick / philippic | 2 / 2 | 0 / 3 | 0 / 2 |

| philosophick / philosophic | 1 / 140 | 0 / 80 | 0 / 155 |

| physick / physic | 35 / 157 | 4 / 51 | 3 / 38 |

| plastick / plastic | 1 / 4 | 0 / 19 | 0 / 32 |

| platonick / platonic | 5 / 48 | 0 / 30 | 0 / 22 |

| politick / politic | 8 / 40 | 2 / 37 | 0 / 51 |

| prognostick / prognostic | 2 / 18 | 0 / 5 | 0 / 1 |

| publick / public | 767 / 3350 | 1 / 3171 | 2 / 2606 |

| relick / relic | 1 / 26 | 4 / 56 | 0 / 65 |

| republick / republic | 12 / 515 | 0 / 185 | 0 / 171 |

| rhetorick / rhetoric | 26 / 109 | 2 / 40 | 0 / 65 |

| rheumatick / rheumatic | 1 / 7 | 0 / 33 | 0 / 30 |

| romantick / romantic | 32 / 191 | 0 / 346 | 0 / 322 |

| rustick / rustic | 3 / 102 | 0 / 157 | 0 / 80 |

| sarcastick / sarcastic | 1 / 37 | 0 / 66 | 0 / 60 |

| sceptick / sceptic | 3 / 26 | 0 / 19 | 0 / 26 |

| scholastick / scholastic | 2 / 24 | 0 / 42 | 0 / 46 |

| sciatick / sciatic | 1 / 1 | 0 / 1 | 0 / 3 |

| scientifick / scientific | 2 / 16 | 0 / 451 | 0 / 814 |

| stoick / stoic | 5 / 34 | 1 / 15 | 0 / 26 |

| sympathetick / sympathetic | 3 / 26 | 0 / 70 | 0 / 248 |

| systematick / systematic | 1 / 13 | 0 / 64 | 0 / 104 |

| topick / topic | 12 / 128 | 0 / 177 | 0 / 176 |

| traffick / traffic | 80 / 67 | 1 / 164 | 0 / 203 |

| tragick / tragic | 4 / 65 | 0 / 65 | 0 / 209 |

| tropick / tropic | 12 / 37 | 0 / 7 | 0 / 23 |

第2期以降 (1780--1920) は,すべての語において事実上 -ic のみとなったとみてよいが,18世紀の大半を含む第1期 (1710--1780) については,ここかしこに保守的な -ick が散見される.語によっては <critick>, <frolick>, <heroick>, <musick>, <panegyrick>, <panick>, <physick>, <publick>, <rhetorick>, <romantick>, <tropick> など そこそこの頻度を示すものもあるし,<traffick> ではむしろ -ic 形よりも優勢だ(なお,屈折語尾としての -ic(k) ではないが,garlick/garlic は,第1期 17 / 7, 第2期 1 / 8, 第3期 0 / 11 を数え,最初期に -ick が優勢だったもう1つの例である).しかし,全体として -ick 形は散見されるにすぎず,すでに18世紀より -ic 形が幅を利かせていたことがわかる.つまり,18世紀半ばの Johnson の辞書では,すでに影の薄くなっていた保守的な -ic が,半ば意識的に採用されたという解釈が成り立ちそうだ.Webster の時代ではなく,Johnson の時代にすでに -ic 形は事実上の市民権を得ていたと考えられる.

しかし,CLMET で得られた後期近代英語の趨勢を歴史の中に適切に位置づけて解釈するためには,先行する初期近代英語における異綴字の分布(変化)も押えておく必要があるだろう.それについては明日の記事で.

2014-08-30 Sat

■ #1951. 英語の愛称 [shortening][personal_name][suffix][onomastics][metanalysis][term_of_endearment][hypocorism]

愛称 (pet name) や新愛語 (term of endearment) は,専門的には hypocorism と呼ばれる.ギリシア語 hupo- "hypo-" + kórisma (cf. kóros (child))) から来ており,子供をあやす表現,小児語ということである.英語の hypocorism の作り方にはいくつかあるが,典型的なものは Robert → Rob のように語形を短くするものである.昨日の記事「#1950. なぜ Bill が William の愛称になるのか?」 ([2014-08-29-1]) でみたように,語頭に音の変異を伴うものもあり,Edward → Ned (cf. mine Ed), Edward → Ted (cf. that Ed?), Ann → Nan (cf. mine Ann) のように前接要素との異分析として説明されることがある.

ほかに,愛称接尾辞 (hypocoristic suffix) -y や -ie を付加する Georgie, Charlie, Johnnie などの例があり,とりわけ女性名に好まれる.また,短縮し,かつ接尾辞をつける Elizabeth → Betty, William → Billy, Richard → Ritchie なども数多い.接尾辞の異形として -sy, -sie もあり,Elizabeth → Betsy/Bessy, Anne → Nancy, Patricia → Patsy などにみられる.

『新英語学辞典』 (542) によれば,歴史的には,接尾辞付加の慣習は15世紀中頃に Charlie などがスコットランドで始まり,それが16世紀以降に各地に広まったものとされる.また,『現代英文法辞典』 (670) によれば,本来は愛称であるから当初は正式名ではなかったが,18世紀から正式名としても公に認められるようになった.

OALD8 の巻末に "Common first names" という補遺があり,省略名や愛称があるものについては,それも掲載されている.以下,そこから取り出したものを一覧にした(括弧を付したものは,別の参考図書から補足したもの).

1. Female names

| Abigail | Abbie |

| Alexandra | Alex, Sandy |

| Amanda | Mandy |

| Catherine, Katherine, Katharine, Kathryn | Cathy, Kathy, Kate, Katie, Katy |

| Christina | Chrissie, Tina |

| Christine | Chris |

| Deborah | Debbie, Deb |

| Diana, Diane | Di |

| (Dorothy) | (Dol) |

| Eleanor | Ellie |

| Eliza | Liza |

| Elizabeth, Elizabeth | Beth, Betsy, Betty, Liz, Lizzie |

| Ellen, Helen | Nell |

| Frances | Fran |

| Georgina | Georgie |

| Gillian | Jill, Gill, Jilly |

| Gwendoline | Gwen |

| Jacqueline | Jackie |

| Janet | Jan |

| Janice, Janis | Jan |

| Jennifer | Jenny, Jen |

| Jessica | Jess |

| Josephine | Jo, Josie |

| Judith | Judy |

| Kristen | Kirsty |

| Margaret | Maggie, (Meg, Peg) |

| (Mary) | (Moll, Poll) |

| Nicola | Nicky |

| Pamela | Pam |

| Patricia | Pat, Patty |

| Penelope | Penny |

| Philippa | Pippa |

| Rebecca | Becky |

| Rosalind, Rosalyn | Ros |

| Samantha | Sam |

| Sandra | Sandy |

| Susan | Sue, Susie, Suzy |

| Susanna(h), Suzanne | Susie, Suzy |

| Teresa, Theresa | Tessa, Tess |

| Valerie | Val |

| Victoria | Vicki, Vickie, Vicky, Vikki |

| Winifred | Winnie |

2. Male names

| Albert | Al, Bert |

| Alexander | Alex, Sandy |

| Alfred | Alfie |

| Andrew | Andy |

| (Anthony) | (Tony) |

| Benjamin | Ben |

| Bernard | Bernie |

| (Boswell) | (Boz) |

| Bradford | Brad |

| Charles | Charlie, Chuck |

| Christopher | Chris |

| Clifford | Cliff |

| Daniel | Dan, Danny |

| David | Dave |

| Douglas | Doug |

| Edward | Ed, Eddie, Eddy, (Ned), Ted |

| Eugene | Gene |

| Francis | Frank |

| Frederick | Fred, Freddie, Freddy |

| Geoffrey, Jeffrey | Geoff, Jeff |

| Gerald | Gerry, Jerry |

| Gregory | Greg |

| Henry | Hank, Harry |

| Herbert | Bert, Herb |

| Jacob | Jake |

| James | Jim, Jimmy, Jamie |

| Jeremy | Jerry |

| John | |

| Johnny | |

| Jonathan | Jon |

| Joseph | Joe |

| Kenneth | Ken, Kenny |

| Laurence, Lawrence | Larry, Laurie |

| Leonard | Len, Lenny |

| Leslie | Les |

| Lewis | Lew |

| Louis | Lou |

| (Macaulay) | (Mac) |

| Matthew | Matt |

| Michael | Mike, Mick, Micky, Mickey |

| Nathan | Nat |

| Nathaniel | Nat |

| Nicholas | Nick, Nicky |

| Patrick | Pat, Paddy |

| (Pendennis) | (Pen) |

| Peter, Pete | |

| Philip | Phil |

| Randolph, Randolf | Randy |

| Raymond | Ray |

| Richard | Rick, Ricky, Ritchie, Dick |

| Robert | Rob, Robbie, Bob, Bobby |

| Ronald | Ron, Ronnie |

| Samuel | Sam, Sammy |

| Sebastian | Seb |

| Sidney, Sydney | Sid |

| Stanley | Stan |

| Stephen, Steven | Steve |

| Terence | Terry |

| Theodore | Theo |

| Thomas | Tom, Tommy |

| Timothy | Tim |

| Victor | Vic |

| Vincent | Vince |

| William | Bill, Billy, Will, Willy |

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

・ 荒木 一雄,安井 稔 編 『現代英文法辞典』 三省堂,1992年.

2014-06-21 Sat

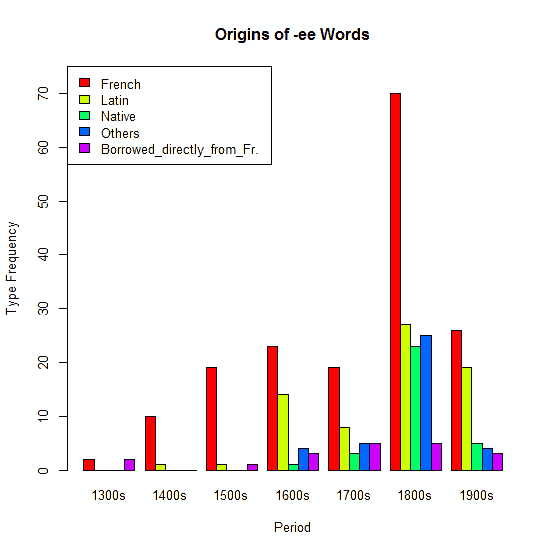

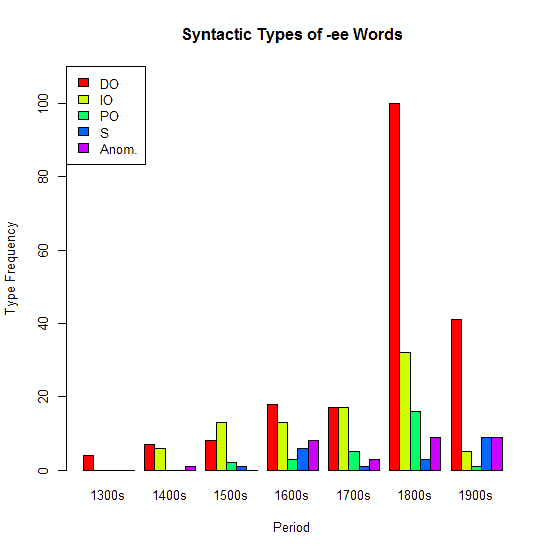

■ #1881. 接尾辞 -ee の起源と発展 (2) [suffix][pde_language_change][lexicology][statistics][oed][productivity][agentive_suffix]

昨日の記事「#1880. 接尾辞 -ee の起源と発展 (1)」 ([2014-06-20-1]) に続き,当該接尾辞の現代英語にかけての質的な変化および量的な発展について,Isozaki に拠りながら考える.

Isozaki は,OED ほかの参考資料に当たり,現代英語から500を超える -ee 語を収集した.そして,これらを初出年代,統語・意味の種別,語幹の語源により分析し,後期近代英語から現代英語にかけての潮流を2点突き止めた.昨日の記事の終わりで述べた,(1) ロマンス系語幹ではなく本来語幹に接続する傾向が生じてきていること,および (2) standee のような動作主(主語)タイプが増えてきていること,の2つである.

(1) については,OED を用いた調査結果をグラフ化すると以下のようになる (Isozaki 7) .

フランス語幹に接続する傾向が一貫して強いことは明らかである.しかし,本来語幹に接続する語例が後期近代より現われてきたことは注目に値する.なお,19世紀の爆発期の後で20世紀が地味に見えるのは,OED の語彙収録の特徴によるところが大きいかもしれない.

次に (2) についてだが,同じく OED を用いて,統語(意味)的な観点から分類した結果は以下の通りである (Isozaki 6) .グラフのなかで,DO は動詞の直接目的語,IO は間接目的語,PO は前置詞目的語,S は主語,Anom. は動詞とは直接に関係しない変則的なものである.

従来型の DO タイプが常に優勢であり続けていることが顕著であり,S タイプの拡張は特に目立たないようにみえる.しかし,OED を離れて,1900--2005年の種々の本や参考図書での出現を考慮に入れると,DO が117例,IO が23例,PO が4例,S が32例,Anom. が18例と,S (主語タイプ)の伸張が示唆される (Isozaki 6) .

-ee 語は臨時語的な使われ方が多いと想像され,使用域の一般化も進んでいるように思われる.今後は語用論的な調査も必要となってくるかもしれない.接辞の生産性 (productivity) という観点からも,アンテナを張っておきたい話題である.

・ Isozaki, Satoko. "520 -ee Words in English." Lexicon 36 (2006): 3--23.

2014-06-20 Fri

■ #1880. 接尾辞 -ee の起源と発展 (1) [suffix][loan_word][french][register][anglo-norman][law_french][etymology][-ate][agentive_suffix][french_influence_on_grammar]

emplóyer (雇い主)に対して employée (雇われている人)というペアはよく知られている.appóinter/appointée, exáminer/examinée, páyer/payée, tráiner/trainée などのペアも同様で,それぞれの組で -er をもつ前者が能動的に動作主を,-ee をもつ後者が受動的に被動作主を表わす.

しかし,absentee (欠席者), escapee (脱走者), patentee (特許権所有者), refugee (避難民), standee (立見客)など,意味的に受け身とは解釈できない例も存在する.実際,standee と stander は同義ではないとしても,少なくとも類義ではある.-ee という接頭辞の働きはどのようなものだろうか.

-er は本来的な接尾辞(古英語 -ere)だが,-ee はフランス語から借用した接尾辞である.フランス語 -é(e) は動詞の過去分詞接尾辞であり,他動詞に接続すれば受け身の意味となった.これ自体はラテン語の第1活用の動詞の過去分詞接辞 -ātus に遡るので,communicatee, dedicatee, educatee, legatee, relocatee などでは同根の2つの接尾辞が付加されていることになる(-ate 接尾辞については,「#1242. -ate 動詞の強勢移行」 ([2012-09-20-1]) や「#1748. -er or -or」 ([2014-02-08-1]) を参照).

接尾辞 -ee の基本的な機能は,動詞語幹から人や有生物を表わす被動作主名詞を作ることである.他の特徴としては,接尾辞 -ee /ˈiː/ に強勢が落ちること,意志性の欠如という意味上の制約があること,法律用語として用いられる傾向が強いこと,などが挙げられる.法律という使用域 (register) についていえば,Anglo-Norman の法律用語 apelour/apelé から英語に入った appellor/appellee (上訴人/被上訴人)などのペアが嚆矢となり,後期中英語以降,基体の語源にかかわらず -or (or -er) と -ee による法律用語ペアが続々と生まれた.

被動作主とひとくくりにいっても,統語的には基体の動詞の直接目的語,間接目的語,前置詞目的語に相当するもの,さらに主語に相当するものや,動詞とは直接に関連しないものを含めて,様々な種類がある (Isozaki 5--6).examinee は "someone who one examines" で直接目的語に相当,payee は "someone to whom one pays something" で間接目的語に相当,laughee は "someone who one laughs at" で前置詞目的語に相当, standee と attendee は "someone who stands" と "someone who attends something" で主語に相当する.その他,変則的な種類として,amputee は "someone whose limb was amputated" と複雑な統語関係を示し,patentee, redundantee, biographee は名詞や形容詞を基体としてもつ.

この接尾辞について後期近代英語から現代英語へかけての通時的推移をみると,ロマンス系語幹ではなく本来語幹に接続する傾向が生じてきていること,standee のような動作主(主語)タイプが増えてきていることが指摘される.この潮流については,明日の記事で.

・ Isozaki, Satoko. "520 -ee Words in English." Lexicon 36 (2006): 3--23.

2014-06-17 Tue

■ #1877. 動詞を作る接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en [prefix][suffix][morphology]

enlighten 「啓蒙する」という動詞では,基体の light に接頭辞の en- と接尾辞の -en が付加されている.名詞が動詞化している例だが,同じような機能の接辞が2つ付いているのが妙といえば妙である.いずれかのみでも良さそうなものだし,実際に接尾辞 -en のみを付加した lighten という動詞が存在する.これらの接辞はどのように使い分けられているのだろうか.

実は,接頭辞 en- と接尾辞 -en の語源はまったく異なっており,接点がない.接頭辞のほうは,ラテン語の接頭辞 in- に由来し,古フランス語を経由して英語に入った借用接辞である.英語の前置詞 in と究極的には同根で「中へ」を原義とし,「中へ入る」「中へ入れる」という運動が感じられるので,動詞を作る接頭辞として機能し始めたのだろう.名詞の基体につくのが基本だが,形容詞やすでに動詞である基体につくこともある (ex. encase, enchain, encradle, enthrone, enverdure; embus, emtram, enplane; engulf, enmesh; empower, encollar, encourage, enfranchise; embitter, enable, endear, englad, enrich, enslave; enfold, enkindle, enshroud, entame, entangle, entwine, enwrap) .基体が動詞の場合,先に話題にした通り接尾辞 -en をともなっているものがあり,embolden, enfasten, engladden, enlighten のような形態が生じている(廃語になったものとして,encolden, enlengthen, enlessen, enmilden, enquicken, enwiden, enwisen もあり).enclose/inclose, encumber/incumber, enquire/inquire, ensure/ensure など en- と in- の交替する例もあるが,語源的には前者はフランス語形,後者はラテン語形である.

一方,接尾辞 -en は,他動詞を作る古英語の接尾辞 -nian に遡る(例えば,古英語の形容詞 fæst (fast) に対する動詞 fæstnian (fasten)).現在の鼻音は,接尾辞 -nian の最後の -n ではなく最初の -n が残ったものである.末尾の形容詞や名詞の基体につき,「?にする」「?になる」の意を表わす.例として,darken, deepen, harden, sharpen, sicken, soften, sweeten; heighten, lengthen, strengthen; steepen など.接尾辞そのものは上記のように古英語に遡るが,上に挙げた派生語の多くは後期中英語や初期近代英語での類推に基づく語形成の結果である.

2014-05-28 Wed

■ #1857. 3単現の -th → -s の変化の原動力 [verb][conjugation][emode][language_change][causation][suffix][inflection][phonotactics][3sp]

「#1855. アメリカ英語で先に進んでいた3単現の -th → -s」 ([2014-05-26-1]),「#1856. 動詞の直説法現在形語尾 -eth は17世紀前半には -s と発音されていた」 ([2014-05-27-1]) と続けて3単現の -th → -s の変化について取り上げてきた.この変化をもたらした要因については諸説が唱えられている.また,「#1413. 初期近代英語の3複現の -s」 ([2013-03-10-1]) で触れた通り,3複現においても平行的に -th → -s の変化が起こっていたらしい証拠があり,2つの問題は絡み合っているといえる.

北部方言では,古英語より直説法現在の人称語尾として -es が用いられており,中部・南部の -eþ とは一線を画していた.したがって,中英語以降,とりわけ初期近代英語での -th → -s の変化は北部方言からの影響だとする説が古くからある.一方で,いずれに方言においても確認された2単現の -es(t) の /s/ が3単現の語尾にも及んだのではないかとする,パラダイム内での類推説もある.その他,be 動詞の is の影響とする説,音韻変化説などもあるが,いずれも決定力を欠く.

諸説紛々とするなかで,Jespersen (17--18) は音韻論の観点から「効率」説を展開する.音素配列における「最小努力の法則」 ('law of least effort') の説と言い換えてもよいだろう.

In my view we have here an instance of 'Efficiency': s was in these frequent forms substituted for þ because it was more easily articulated in all kinds of combinations. If we look through the consonants found as the most important elements of flexions in a great many languages we shall see that t, d, n, s, r occur much more frequently than any other consonant: they have been instinctively preferred for that use on account of the ease with which they are joined to other sounds; now, as a matter of fact, þ represents, even to those familiar with the sound from their childhood, greater difficulty in immediate close connexion with other consonants than s. In ON, too, þ was discarded in the personal endings of the verb. If this is the reason we understand how s came to be in these forms substituted for th more or less sporadically and spontaneously in various parts of England in the ME period; it must have originated in colloquial speech, whence it was used here and there by some poets, while other writers in their style stuck to the traditional th (-eth, -ith, -yth), thus Caxton and prose writers until the 16th century.

言語の "Efficiency" とは言語の進歩 (progress) にも通じる.(妙な言い方だが)Jespersen だけに,実に Jespersen 的な説と言えるだろう.Jespersen 的とは何かについては,「#1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観」 ([2014-01-19-1]) を参照されたい.[s] と [θ] については,「#842. th-sound はまれな発音か」 ([2011-08-17-1]) と「#1248. s と th の調音・音響の差」 ([2012-09-26-1]) もどうぞ.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part VI. Copenhagen: Ejnar Munksgaard, 1942.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow