2013-03-05 Tue

■ #1408. インク壺語論争 [popular_passage][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek][purism]

16世紀のインク壺語 (inkhorn term) を巡る問題の一端については,昨日の記事「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) 以前にも,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) ,「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で触れてきた.インク壺語批判の先鋒としては,[2010-11-24-1]で引用した The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) の著者 Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) が挙げられるが,もう1人挙げるとするならば Sir John Cheke (1514--57) がふさわしい.Cheke は自らがギリシア語学者でありながら,古典語からのむやみやたらな借用を強く非難した.同じくギリシア語学者である Roger Ascham (1515?--68) も似たような態度を示していた点が興味深い.Cheke は Sir Thomas Hoby に宛てた手紙 (1561) のなかで,純粋主義の主張を行なった(Baugh and Cable, pp. 217--18 より引用).

I am of this opinion that our own tung shold be written cleane and pure, unmixt and unmangeled with borowing of other tunges, wherin if we take not heed by tijm, ever borowing and never payeng, she shall be fain to keep her house as bankrupt. For then doth our tung naturallie and praisablie utter her meaning, when she bouroweth no counterfeitness of other tunges to attire her self withall, but useth plainlie her own, with such shift, as nature, craft, experiens and folowing of other excellent doth lead her unto, and if she want at ani tijm (as being unperfight she must) yet let her borow with suche bashfulnes, that it mai appeer, that if either the mould of our own tung could serve us to fascion a woord of our own, or if the old denisoned wordes could content and ease this neede, we wold not boldly venture of unknowen wordes.

Erasmus の Praise of Folly を1549年に英訳した Sir Thomas Chaloner も,インク壺語の衒学たることを揶揄した(Baugh and Cable, p. 218 より引用).

Such men therfore, that in deede are archdoltes, and woulde be taken yet for sages and philosophers, maie I not aptelie calle theim foolelosophers? For as in this behalfe I have thought good to borowe a littell of the Rethoriciens of these daies, who plainely thynke theim selfes demygods, if lyke horsleches thei can shew two tongues, I meane to mingle their writings with words sought out of strange langages, as if it were alonely thyng for theim to poudre theyr bokes with ynkehorne termes, although perchaunce as unaptly applied as a gold rynge in a sowes nose. That and if they want suche farre fetched vocables, than serche they out of some rotten Pamphlet foure or fyve disused woords of antiquitee, therewith to darken the sence unto the reader, to the ende that who so understandeth theim maie repute hym selfe for more cunnyng and litterate: and who so dooeth not, shall so muche the rather yet esteeme it to be some high mattier, because it passeth his learnyng.

"foolelosophers" とは厳しい.

このようにインク壺語批判はあったが,時代の趨勢が変わることはなかった.インク壺語を(擁護したとは言わずとも)穏健に容認した Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546) や Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) などの主たる人文主義者たちの示した態度こそが,時代の潮流にマッチしていたのである.

なお,OED によると,ink-horn term という表現の初出は1543年.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-04 Mon

■ #1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題 [emode][renaissance][popular_passage][orthoepy][orthography][spelling_reform][standardisation][mulcaster][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicology][hart]

初期近代英語期,特に16世紀には英語を巡る大きな問題が3つあった.Baugh and Cable (203) の表現を借りれば,"(1) recognition in the fields where Latin had for centuries been supreme, (2) the establishment of a more uniform orthography, and (3) the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" である.

(1) 16世紀は,vernacular である英語が,従来ラテン語の占めていた領分へと,その機能と価値を広げていった過程である.世紀半ばまでは,Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Thomas Wilson (1525?--81) , George Puttenham (1530?--90) に代表される英語の書き手たちは,英語で書くことについてやや "apologetic" だったが,世紀後半になるとそのような詫びも目立たなくなってくる.英語への信頼は,特に Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) の "I love Rome, but London better, I favor Italie, but England more, I honor the Latin, but I worship the English." に要約されている.

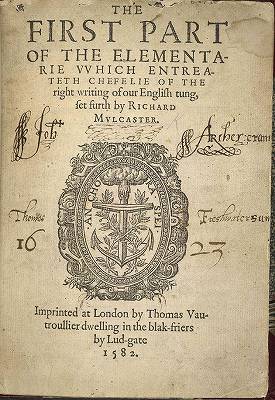

(2) 綴字標準化の動きは,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Sir Thomas Smith (1513--77; De Recta et Emendata Linguae Anglicae Scriptione Dialogus [1568]), John Hart (d. 1574; An Orthographie [1569]), William Bullokar (fl. 1586; Book at Large [1582], Bref Grammar for English [1586]) などによる急進的な表音主義的な諸提案を経由して,Richard Mulcaster (The First Part of the Elementarie [1582]), E. Coot (English Schoole-master [1596]), P. Gr. (Paulo Graves?; Grammatica Anglicana [1594]) などによる穏健な慣用路線へと向かい,これが主として次の世紀に印刷家の支持を受けて定着した.

(3) 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で繰り返し述べてきたように,16世紀は主としてラテン語からおびただしい数の借用語が流入した.ルネサンス期の文人たちの多くが,Sir Thomas Elyot のいうように "augment our Englysshe tongue" を目指したのである.

vernacular としての初期近代英語の抱えた上記3つの問題の背景には,中世から近代への急激な社会変化があった.再び Baugh and Cable (200) を参照すれば,その要因は5つあった.

1. the printing press

2. the rapid spread of popular education

3. the increased communication and means of communication

4. the growth of specialized knowledge

5. the emergence of various forms of self-consciousness about language

まさに,文明開化の音がするようだ.[2012-03-29-1]の記事「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2012-09-09 Sun

■ #1231. drift 言語変化観の引用を4点 [drift][causation][language_change][popular_passage]

言語変化の原動力として,drift を想定する言語論者は,今もって少なくない.drift の問題として,特に「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]) と「#686. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (2)」 ([2011-03-14-1]) の記事で議論したが,近年,新たな視点からこの問題に迫っているのがウィーン大学の Ritt である.Ritt の言語変化観は刺激的だと思っているが,彼の最近の論文 (p. 131) で,drift を支持する研究者からの重要な引用が4点ほどなされていたので,それを再現したい(便宜のため,引用元の典拠は展開しておく).

Languages . . . came into being, grew and developed according to definite laws, and now, in turn, age and die off . . . (Schleicher, August. Die Darwinsche Theorie und die Sprachwissenschaft: offenes Sendschreiben an Herrn Dr. Ernst Häckel. Weimar: H. Böhlau, 1873. Page 16.)

Language moves down time in a current of its own making. It has a drift. (Sapir, Edward. Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921. Page 151.)

A living language is not just a collection of autonomous parts, but, as Sapir (1921) stressed, a harmonious and self-contained whole, massively resistant to change from without, which evolves according to an enigmatic, but unmistakably real, inner plan. (Donegan, Patricia Jane and David Stampe. "Rhythm and the Holistic Organization of Language Structure." Papers from the Parasession on the Interplay of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. Eds. John F. Richardson, Mitchell Marks, and Amy Chukerman. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, 1983. 337--53. Page 1.)

languages . . . are objects whose primary mode of existence is in time . . . which ought to be viewed as potentially having extended (trans-individual, transgenerational) 'lives of their own'. (Lass, Roger. "Language, Speakers, History and Drift." Explanation and Linguistic Change. Eds. W. F. Koopman, Frederike van der Leek, Olga Fischer, and Roger Eaton. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1987. 151--76. Pages 156--57.).

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

2011-11-12 Sat

■ #929. 中英語後期,イングランド中部方言が標準語の基盤となった理由 [popular_passage][me_dialect][standardisation][chancery_standard]

中英語は「方言の時代」と呼ばれるほど,方言が花咲き,それが書き言葉にも如実に反映された時期である.それほど異なっていたのであれば,はたして当時のイングランド各地の人々は互いにコミュニケーションを取ることができたのだろうか,という素朴な疑問が持ち上がる.[2010-03-30-1]の記事「#337. egges or eyren」で紹介した Caxton の有名な逸話を読むと,少なくともイングランドの南北方言間では部分的な意志疎通の障害があったことが具体的に理解できる.日本語の方言事情を考えれば,逸話内の夫人の当惑も手に取るように分かるだろう.

中英語も後期になってくると,緩やかな書き言葉の標準というべきものが現われてくる.現在の書き言葉標準のような固定化した (fixed) 標準ではなく,むしろ現在の話し言葉標準のような中心を指向する (focused) 標準に近い.当時現われ始めた書き言葉標準は,諸方言の混じり合ったものではあったが,その中でも基盤となった方言は中部方言である.これはなぜだろうか.なぜ北部や南部の方言がベースとならなかったのだろうか.

1つには,政治や文化の中心地としてのロンドンで話され,書かれていた英語,特に公文書に用いられていた Chancery Standard の影響力がある.言語的標準を目指す上で,社会的権威を付されている首都の公式の語法を参照するというのは自然な発想である.ロンドンの方言は,方言学的には中部と南部の両方言の境目に当たるのだが,少なくとも北部方言に対する中部・南部方言の優位性はこれで確保される.

2つ目として,中部方言が,教養の香りを漂わせる London, Oxford, Cambridge の作る三角地帯で用いられていた方言と重なっていたという事情がある.これによって,中部方言は学問的,文化的な権威をも付されることとなった.

3つ目に,中部方言は地理的にも南北両方言の中間に位置しているため,両方言の要素を兼ね備えており,方言の花咲くイングランドにおいてリンガフランカとして機能し得たと考えられる.この点については,Ranulph Higden (c. 1280--1364) によるラテン語の歴史書 Polychronicon を1387年に英語へ翻訳した John of Trevisa (1326--1402) より,Mossé 版 (288--89) から次の箇所を引用しよう.

. . . for men of þe est wiþ men of þe west, as hyt were undur þe same party of hevene, acordeþ more in sounyng of speche þan men of þe north wiþ men of þe souþ; þerfore hyt ys þat Mercii, þat buþ men of myddel Engelond, as hyt were parteners of þe endes, undurstondeþ betre þe syde longages, Norþeron and Souþeron, þan Norþeron and Souþeron understondeþ eyþer oþer.

[2011-11-10-1]の記事「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」で北西ヨーロッパにおける地理と言語の間接的な結びつきを話題にしたが,イングランド国内というより小さなレベルでも地理が言語において間接的な意味をもつということを,この3つ目の事情は示しているのではないか.

・ Mossé, Fernand. A Handbook of Middle English. Trans. James A. Walker. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1952.

2011-05-14 Sat

■ #747. 記述と規範 [prescriptive_grammar][popular_passage]

英語を数年間学んで大学に入学してきた学生が,言語学の授業で最初に習うことの1つに記述 (description) と規範 (prescription) の違いがある.言語学において,記述文法 (descriptive grammar) と規範文法 (prescriptive grammar) の区別は最重要項目である.

記述とは言語のあるがままの姿を記録することであり,規範とは言語のあるべき姿を規定するものである.言語学は言語の現実を観察して記録することを使命とする科学なので,「かくあるべし」という規範的なフィルターを通して言語を扱うことをしない.文法や語法が「すぐれている」,「崩れている」,「誤っている」という価値判断はおよそ規範文法に属し,言語学の立場とは無縁である.確かに,規範文法そのものを論じる言語教育や応用言語学の領域はあるし,英語史でも英語規範文法の成立の過程は重要な話題である (prescriptive_grammar) .しかし,言語学は原則として記述と規範を峻別し,原則として前者に関心を寄せるということを理解しておく必要がある.

記述を規範に優先させる理由としては,以下の点を考えるとよい.

・ 一般に科学はあるべき姿を論じるのではなく,現実の姿を観察し,理論化し,解説(記述)しようとするものである.言語学も例外ではない.

・ いかなる言語社会も(いまだ記述されていないとしても)記述されるべき文法をもっているが,すべての言語社会が規範文法をもっているとは限らない,あるいは必要としているとは限らない.実際に,規範文法をもっていない言語社会は多く存在する.英語の規範文法も18世紀の産物にすぎない.

・ 規範は価値観を含む「道徳」に近いものであり,時代や地域によっても変動する.個人的,主観的な色彩も強い.「道徳」は科学になじまない.

大学生,とりわけ英語学を学ぶ英文科の学生は,記述と規範の区別を明確に理解していなければならない.というのは,「実践英文法」などの実用英語の授業(規範文法)があるかと思えば,次の時間に「英語学概論」などの英語学の授業(記述文法)が控えていたりするからだ.2つは英語に対するモードがまるで異なるので,頭を180度切り換えなければならない.

記述と規範の峻別についてはどの言語学入門書にも書かれていることだが,Martinet (31) による一般言語学の名著の冒頭から拙訳とともに引用しよう.

La linguistique est l'étude scientifique du langage humain. Une étude est dite scientifique lorsqu'elle se fonde sur l'observation des fait et s'abstient de proposer un choix parmi ces faits au nom de certains principes esthétiques ou moraux. «Scientifique» s'oppose donc à «prescriptif». Dans le cas de la linguistique, il est particulièrement important d'insister sur le caractère scientifique et non prescriptif de l'étude : l'objet de cette science étant une activité humaine, la tentation est grande de quitter le domaine de l'observation impartiale pour recommander un certain comportement, de ne plus noter ce qu'on dit réellement, mais d'édicter ce qu'il faut dire. La difficulté qu'il y a à dégager la linguistique scientifique de la grammaire normative rappelle celle qúil y a à dégager de la morale une véritable science des mœurs.

言語学は人間の言語の科学的研究である.

ある研究が科学的と言われるのは,それが事実の観察にもとづいており,ある審美的あるいは道徳的な規範の名のもとに事実の取捨選択を提案することを差し控えるときである.したがって,「科学的」は「規範的」に対立する.言語学においては,研究の科学的で非規範的な性質を強調することがとりわけ重要である.この科学の対象は人間活動であるため,公平無私な観察の領域を離れてある行動を推薦する方向に進み,実際に言われていることにもはや留意せず,かく言うべしと規定したいという気持ちになりがちである.科学的言語学から規範文法を取り除くことの難しさは,生活習慣に関する真の科学から道徳を取り除く難しさを想起させる.

・ Martinet, André. Éléments de linguistique générale. 5th ed. Armand Colin: Paris, 2008.

2011-01-17 Mon

■ #630. blend(ing) あるいは portmanteau word の呼称 [word_formation][morphology][popular_passage][terminology][blend][contamination]

blend 「混成語」は blending 「混成」という語形成によって作られる語である.最も有名な混成語の1つは brunch だろう.breakfast + lunch をつづめたもので,2語を1語に圧縮したものである.複数のものを1つの入れ物に詰め込むイメージで,かばん語 ( portmanteau word ) と呼ばれることも多い( portmanteau は OADL8 によると "consisting of a number of different items that are combined into a single thing" ).

portmanteau word という表現は,Lewis Carroll 著 Through the Looking-Glass (1872) の6章で Alice と Humpty Dumpty が交わしている会話から生まれた表現である.Alice は,鏡の国の不思議な詩 "JABBERWOCKY" の最初の1節を Humpty Dumpty に示した.

'Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

これに対して Humpty Dumpty が一語一語解説してゆくのだが,1行目の slithy について次のように述べている.

'Well, "slithy" means "lithe and slimy." "Lithe" is the same as "active." You see it's like a portmanteau --- there are two meanings packed up into one word.'

同様に3行目の mimsy についても,"flimsy and miserable" の portmanteau word として説明を加えている.

より術語らしい響きをもつ blending という呼称については,OED によると初例は Henry Sweet 著 "New English Grammar" (1892) に見いだされる.

Grammatical and logical anomalies often arise through the blending of two different constructions.

通常 blending とは2語を基にした意識的な造語過程を指すが,2語の意味の同時想起によって生じる無意識の混乱に基づいた needcessity ( need + necessity ) のような例も含みうる.ただし,後者は contamination 「混同」として区別されることもある.

blending は語形成の一種として広く知られているためにその陰であまり知られていないが,文法的な「混成」の現象もある."Why did you do that?" と "What did you do that for?" が混成して "Why did you do that for?" なる表現が表出したり,"different from" と "other than" から新しく "different than" が生じたりする例である.日本語の「火蓋を切る」と「幕を切って落とす」が混成して「火蓋を切って落とす」となるのも同様の例である.

2010-11-24 Wed

■ #576. inkhorn term と英語辞書 [emode][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicography][cawdrey][lexicology][popular_passage]

[2010-08-18-1]の記事で「インク壺語」( inkhorn term )について触れた.16世紀,ルネサンスの熱気にたきつけられた学者たちは,ギリシア語やラテン語から大量に語彙を英語へ借用した.衒学的な用語が多く,借用の速度もあまりに急だったため,これらの語は保守的な学者から inkhorn terms と揶揄されるようになった.その代表的な批判家の1人が Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) である.著書 The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) で次のように主張している.

Among all other lessons this should first be learned, that wee never affect any straunge ynkehorne termes, but to speake as is commonly received: neither seeking to be over fine nor yet living over-carelesse, using our speeche as most men doe, and ordering our wittes as the fewest have done. Some seeke so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mothers language.

Wilson が非難した "ynkehorne termes" の例としては次のような語句がある.ex. revolting, ingent affabilitie, ingenious capacity, magnifical dexteritie, dominicall superioritie, splendidious.このラテン語かぶれの華美は,[2010-02-13-1]の記事で触れた15世紀の aureate diction 「華麗語法」の拡大版といえるだろう.

inkhorn controversy は16世紀を通じて続くが,その副産物として英語史上,重要なものが生まれることになった.英語辞書である.inkhorn terms が増えると,必然的に難語辞書が求められるようになった.Robert Cawdrey (1580--1604) は,1604年に約3000語の難語を収録し,平易な定義を旨とした A Table Alphabeticall を出版した(表紙の画像はこちら.そして,これこそが後に続く1言語使用辞書 ( monolingual dictionary ) すなわち英英辞書の先駆けだったのである.現在,EFL 学習者は平易な定義が売りの各種英英辞書にお世話になっているが,その背景には16世紀の inkhorn terms と inkhorn controversy が隠れていたのである.

A Table Alphabeticall については,British Museum の解説が有用である.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2010-10-13 Wed

■ #534. The General Prologue の冒頭の現在形と完了形 [chaucer][tense][aspect][popular_passage][perfect][voicy]

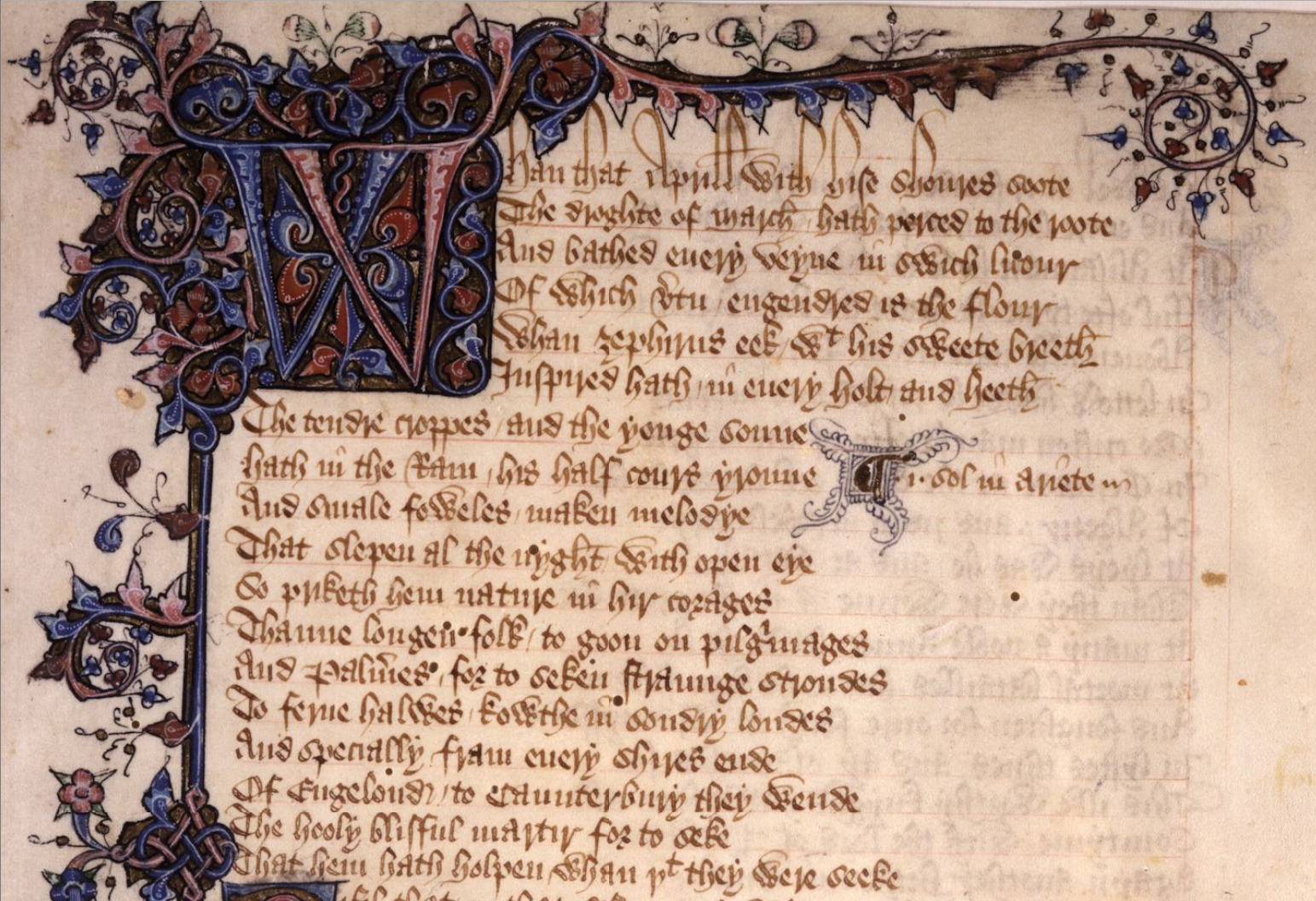

Chaucer の The Canterbury Tales の "The General Prologue" から,あまりにも有名な冒頭の1文を引く( ll. 1--18 from The Riverside Chaucer )

Whan that Aprill with his shoures soote

The droghte of March hath perced to the roote,

And bathed every veyne in swich licour

Of which vertu engendred is the flour;

Whan Zephirus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes, and the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his half cours yronne,

And smale foweles maken melodye,

That slepen al the nyght with open ye

(So priketh hem nature in hir corages),

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

To ferne halwes, kowthe in sondry londes;

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende,

The hooly blisful martir for to seke,

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

初めて読んだ中英語の文章がこの文だったという人も多いのではないだろうか.格調の高い長い書き出しだが,基本的な文の構造としては Whan . . . Thanne の相関構文であり明快だ.この文の味わい方は読者の数だけあるのかもしれないが,今回は Burnley (46--47) に従って時制 ( tense ) と相 ( aspect ) に注目した読み方を紹介したい.

まず,用いられている動詞の時制はほぼ現在で統一されている(唯一の例外は最後の行の were のみ).語りの前提のない書き出しでの現在形使用は,普遍性を感じさせる.4月が訪れ,自然が目覚め出すと同時に,人もやむにやまれずカンタベリーへの巡礼を思い立つ,ということが毎年のように繰り返されていることが暗示される.自然の循環,季節の回帰を想起させる,高らかな謳いだしである.

相 ( aspect ) に目を移すと,Whan 節の内部では主として完了形が用いられている.これは Whan 節とそれに続く Thanne 節の内容が時間的に間をおかずに継起していることを示すとともに,単に時間的継起のみならず因果関係をも示唆している.人々が巡礼を思い立つのは,他ならぬ4月の自然の引き金によるものなのだ.長い文でありながら,Whan 節と That 節の内容が緊密に結びついているのは,完了形の力ゆえである.

まとめれば,この冒頭の文では「自然の目覚め→人々の目覚め」という因果関係が毎年のように繰り返されるという普遍性を謳っていることになる.この文の後には "Bifil that in that seson on a day," と過去形での語りが始まるので,対照的に冒頭の現在時制とそれが含意する普遍性が際立つことになる.以上,有名な冒頭を時制と相によって読んでみた.

(後記 2022/05/03(Tue):Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて,この1節を中英語の発音で読み上げていますのでご参照ください.「中英語をちょっとだけ音読 チョーサーの『カンタベリ物語』の冒頭より」です.)

(後記 2023/10/10(Tue):Ellesmere MS の冒頭部分の画像は です.)

です.)

・ Burnley, David. The Language of Chaucer. Basingstoke: Macmillan Education, 1983. 13--15.

2010-08-08 Sun

■ #468. アメリカ語を作ろうとした Webster [popular_passage][ame][ame_bre][webster][spelling_reform][johnson]

英語の英米差については,これまでも様々に話題にしてきた ( see ame_bre ) .特に綴字の差については発音の差と同様に目につきやすいので話題として取り上げられることが多く,本ブログでも[2009-12-23-1]で話題にした.

ameba, center, color, defense, program, traveler など,イギリス綴りとは異なる独自のアメリカ綴字を提案したのは Noah Webster (1758--1843) である.Webster といえば,1828年に出版された The American Dictionary of the English Language があまりにも有名である.この辞書とその子孫は現在に至るまで質量ともにアメリカ英語辞書の最高峰といわれており,これだけでも Webster の圧倒的な影響力が知れよう.Webster の改革した綴字は当然この辞書にも反映されており,辞書とともにアメリカに広く知れ渡ることとなった.

では,Webster はなぜ綴字改革を始めようと思い立ったのだろうか.それを考える前に,イギリスでの綴字の状況を概観しておこう.中英語後期の Caxton による活版印刷術の導入や初期近代英語期の大母音推移 ( Great Vowel Shift ) など,言語内外の変化を経て,英語は綴字と発音の乖離という頭の痛い問題を抱えることとなった.イギリスでは16世紀から正音学者 ( orthoepist ) が現われ始め,数々の綴字改革案を提案したが,いずれも大きな成功を収めるにはいたらなかった( Mulcaster の改革については[2010-07-12-1]を参照).結局,イギリスでは1755年に Samuel Johnson が著した A Dictionary of the English Language をもって現代の綴字がほぼ固定したといってよい.

一方,大西洋を越えた先の植民地,アメリカでも綴字についてはイギリスと歩調を合わせていた.ところが,18世紀後半の独立前後からアメリカの態度が変わってくる.歴史の多くの例が示している通り,政治的な独立の志向と言語的な独立の志向は表裏一体である.アメリカの政治的な独立の前後の時代には,強烈な愛国心に裏打ちされたアメリカ英語信奉者が現われた.Webster もその1人であり,イギリス英語のアメリカ版ではない独立した「アメリカ語」( the American language ) を打ちたてようと考えていたのである.以下は Webster の言葉である.

The question now occurs; ought the Americans to retain these faults which produce innumerable inconveniences in the acquisition and use of the language, or ought they at once to reform these abuses, and introduce order and regularity into the orthography of the American tongue? . . . . a capital advantage of this reform . . . would be, that it would make a difference between the English orthography and the American. . . . a national language is a band of national union. . . . Let us seize the present moment, and establish a national language as well as a national government. (Webster, 1789 quoted in Graddol, p. 6)

表面的には,英語の綴字と発音の乖離の問題に合理的な解答を与えようという旗印を掲げながら,実のところは,アメリカの国家としての独立,イギリスに対する独自のアイデンティティといった政治的な意図が濃厚であった.過去との決別という非常に強い意志が Webster のみならず多くのアメリカの民衆に横溢していたからこそ,通常は成功する見込みのない綴字改革が功を奏したのだろう.

逆にいえば,この例は相当にポジティブな条件が揃わないと綴字改革は成功しにくいことをよく示している.というのは,Webster ですら,当初抱いていた急進的な綴字改革案を引っ込めなければならなかったからである.彼は当初の案が成功しなさそうであることを見て取り,上記の center や color などの軽微な綴字の変更のみを訴える穏健路線に切り替えたのだった.

現代の綴字における英米差が確立した経緯には,Webster とその同時代のアメリカ人が作り上げた「アメリカ語」への想いがあったのである.

・ Webster, Noah. "An Essay on the Necessity, Advantages and Practicability of Reforming the Mode of Spelling, and of Rendering the Orthography of Words Correspondent to the Pronunciation." Appendix to Dissertations on the English Language. 1789. Extracts reprinted in Proper English?: Readings in Language, History and Cultural Identity. Ed. Tony Crowley. London: Routledge, 1991.

・ Graddol, David. The Future of English? The British Council, 1997. Digital version available at http://www.britishcouncil.org/learning-research-futureofenglish.htm.

2010-07-12 Mon

■ #441. Richard Mulcaster [orthoepy][orthography][spelling_reform][spelling_pronunciation_gap][popular_passage][mulcaster][hart]

[2010-07-06-1]の記事で <oa> の綴字との関連で Richard Mulcaster という名に触れたが,今日は英語綴字改革史におけるこの重要人物を紹介したい.

Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) は,Merchant-Taylors' School の校長,そして後には St. Paul's School の校長を歴任した16世紀後半のイングランド教育界の重鎮である.かの Edmund Spenser の師でもあった.彼の教育論は驚くほど現代的で,教師を養成する大学の設立,教師の選定と給与の問題,よい教師に最低年次を担当させる方針,教師と親の関係,個性に基づいたカリキュラム作成など,250年後にようやく一般に受け入れられることになる数々の提言をした.彼はこうした教育的な動機から英語の綴字改革にも関心を寄せ始め,1582年に保守派を代表する書 The First Part of the Elementarie を世に送った(文法を扱うはずだった The Second Part は出版されなかった).

16世紀は大母音推移 ( Great Vowel Shift ) が進行中で,綴字と発音の乖離の問題が深刻化し始めていた.多数の正音学者 ( orthoepist ) が輩出し,この問題を論じたが,大きく分けて急進派と保守派に分かれていた.急進派は,一文字が一音に厳密に対応するような文字体系を目指す表音主義の名の下に,新しい文字や文字の使い方を提案した.John Cheke (1514--57),Thomas Smith (1513--77), John Hart (d. 1574), William Bullokar (1530?--1590?) などが急進派の代表的な論者である.

それに対して,伝統的・慣習的な綴字の中に固定化の基準を見つけ出そうとする現実即応主義をとるのが保守派で,Richard Mulcaster を筆頭に,1594年に Grammatica Anglicana を著した P. Gr. なる人物 ( Paulo Graves? ) や 1596年に English Schoole-Maister を著した E. Coote などがいた.急進的な表音主義路線はいかにも学者的であるが,それに対して保守的な現実路線をとる Mulcaster は綴字が発音をそのまま表すことはあり得ないという思想をもっていた.綴字と発音の関係の本質を見抜いていたのである.結果としては,この保守派の現実的な路線が世論と印刷業者に支持され,Coote の著書が広く普及したこともあって,後の綴字改革の方向が決せられた.17世紀後半までには綴字はおよそ現代のそれに固定化されていたと考えてよい.18世紀にも論争が再燃したが,保守派の Samuel Johnson による A Dictionary of the English Language (1755) により,綴字はほぼ現代の状態へ固定化した.現代英語の綴字体系の是非はともかくとして,そのレールを敷いた重要人物として Mulcaster の英語史上の役割は大きかったといえるだろう.

Mulcaster は,イングランドが力をつけはじめた Elizabeth 朝の時代に,英語の独立と卓越に確信をもった教育者だった.彼の英語に対する信頼と自信は,著書 The First Part of the Elementarie からの次の有名な文に表れている.

I loue Rome, but London better, I fauor Italie, but England more, I honor the Latin, but I worship the English.

・ Mulcaster, Richard. The First Part of the Elementarie. Menston: Scolar Reprint 219, 1582. (downloadable here from OTA)

2010-05-21 Fri

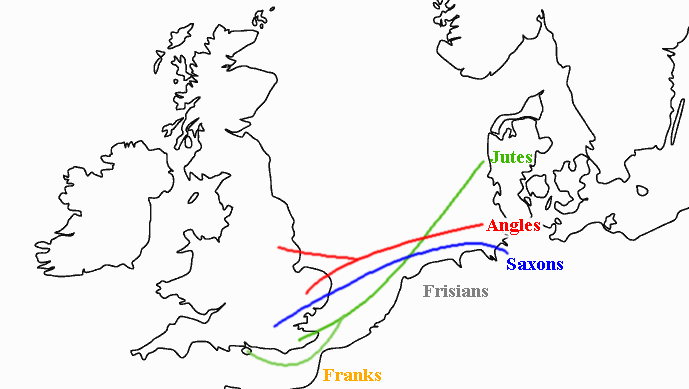

■ #389. Angles, Saxons, and Jutes の故地と移住先 [jute][history][germanic][popular_passage][dialect][kyng_alisaunder][map][anglo-saxon]

英語の歴史は,449年に北ドイツや南デンマークに分布していたアングル人 ( Angles ),サクソン人 ( Saxons ),ジュート人 ( Jutes ) の三民族が西ゲルマン語派の方言を携えてブリテン島に渡ってきたときに始まる ( see [2009-06-04-1] ).ケルトの王 Vortigern が,北方民族を撃退してくれることを期待して大陸の勇猛なゲルマン人を招き寄せたということが背景にある.その年を限定的に449年と言えるのは,古英語期の学者 Bede による The Ecclesiastical History of the English People という歴史書にその記述があるからである.この記述は後に The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle にも受け継がれ,ブリテン島における英語を含めた Anglo-Saxon の伝統の創始にまつわる神話として,現在に至るまで広く言及されてきた.The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle の北部系校訂本の代表である The Peterborough Chronicle の449年の記述から,有名な一節を古英語で引用しよう.現代英語訳とともに,Irvine (35) より抜き出したものである.

Ða comon þa men of þrim megðum Germanie: of Aldseaxum, of Anglum, of Iotum. Of Iotum comon Cantwara 7 Wihtwara, þet is seo megð þe nu eardaþ on Wiht, 7 þet cyn on Westsexum þe man nu git hæt Iutnacynn. Of Ealdseaxum coman Eastseaxa 7 Suðsexa 7 Westsexa. Of Angle comon, se a syððan stod westig betwix Iutum 7 Seaxum, Eastangla, Middelangla, Mearca and ealla Norþhymbra.

PDE translation: Those people came from three nations of Germany: from the Old Saxons, from the Angles, and from the Jutes. From the Jutes came the inhabitants of Kent and the Wihtwara, that is, the race which now dwells in the Isle of Wight, and that race in Wessex which is still called the race of the Jutes. From the Old Saxons came the East Saxons, the South Saxons, and the West Saxons. From the land of the Angles, which has lain waste between the Jutes and the Saxons ever since, came the East Anglians, the Middle Anglians, the Mercians, and all of the Northumbrians.

この一節に基づいて形成されてきた移住神話 ( migration myth ) は,いくつかの事実を覆い隠しているので注意が必要である.449年は移住の象徴の年として理解すべきで,実際にはそれ以前からゲルマン民族が大陸よりブリテン島に移住を開始していた形跡がある.また,449年に一度に移住が起こったわけではなく,5世紀から6世紀にかけて段階的に移住と定住が繰り返されたということもある.他には,アングル人,サクソン人,ジュート人の三民族の他にフランク人 ( Franks ) もこの移住に加わっていたとされる.同様に,現在では疑問視されてはいるが,フリジア人 ( Frisians ) の混在も議論されてきた.移住の詳細については,いまだ不明なことも多いようである ( Hoad 27 ).

上の一節にもあるとおり,主要三民族は大陸のそれぞれの故地からブリテン島のおよそ特定の地へと移住した.大雑把に言えば,ジュート人は Kent や the Isle of Wight,サクソン人はイングランド南部へ,アングル人はイングランド北部や東部へ移住・定住した(下の略地図参照).古英語の方言は英語がブリテン島に入ってから分化したのではなく,大陸時代にすでに分化していた三民族の方言に由来すると考えられる.

西ゲルマン諸民族のなかで,特に Jutes の果たした役割については[2009-05-31-1]を参照.また,上の一節については,オンラインからも古英語と現代英語訳で参照できる.

・ Irvin, Susan. "Beginnings and Transitions: Old English." The Oxford History of English. Ed. Lynda Mugglestone. Oxford: OUP, 2006. 32--60.

・ Hoad, Terry. "Preliminaries: Before English." The Oxford History of English. Ed. Lynda Mugglestone. Oxford: OUP, 2006. 7--31.

2010-04-02 Fri

■ #340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評 [old_norse][loan_word][popular_passage][etymology]

古ノルド語の英語への影響については,いくつか過去の記事で話題にした ( see old_norse ).今回は,日本の英語学にも多大な影響を与えたデンマークの学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) の評を紹介する.北欧語の英語への影響が端的かつ印象的に表現されている.

Just as it is impossible to speak or write in English about higher intellectual or emotional subjects or about fashionable mundane matters without drawing largely upon the French (and Latin) elements, in the same manner Scandinavian words will crop up together with the Anglo-Saxon ones in any conversation on the thousand nothings of daily life or on the five or six things of paramount importance to high and low alike. An Englishman cannot thrive or be ill or die without Scandinavian words; they are to the language what bread and eggs are to the daily fare. (74)

"popular passage" かどうかは微妙だが,複数の文献で引用されている記憶がある.実際,私も説明の際によく引き合いに出す.

Jespersen 自身が北欧人ということもあって,出典の Growth and Structure of the English Language では北欧語の扱いが手厚い.しかし,本書では北欧語だけでなく諸外国語が英語に与えた影響の全般について,説明が丁寧で詳しい.外面史と英語語彙という点に関心がある人には,まずはこの一冊と推薦できるほどにたいへん良質な英語史の古典である.

イギリス留学中は安くあがるトースト・エッグで朝食をすませていたこともあった.bread にせよ egg にせよ,語源は英語でなく古ノルド語にあったわけである.対応する本来語は,それぞれ古英語の形で hlāf ( > PDE loaf ) と ǣg だったが,ヴァイキングの襲来に伴う言語接触とそれ以降の長い歴史の果てに,現代標準語では古ノルド語の対応語 bread と egg が使われるようになっている.(だが,正確にいうと bread につらなる古英語の単語 brēad が「小片」の意で存在していた.「パン」の意味は対応する北欧語の brauð に由来するとされ,少なくとも意味の上での影響があったことは確からしい.)

bread については[2009-05-21-1]を,egg については[2010-03-30-1]を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2010-03-30 Tue

■ #337. egges or eyren [caxton][popular_passage][plural][me_dialect][inflection][spelling]

あまたある英語史の本のなかで繰り返し引用される,古い英語で書かれた一節というものがいくつか存在する.そういったパッセージを順次このブログに追加していき,いずれ popular_passage などというタグのもとで一覧できると,再利用のためにも便利かと思った.そこで,今日は「卵」を表す後期中英語の名詞の複数形の揺れについて Caxton が1490年に Eneydos の序文で挙げている逸話を紹介する.北部出身とおぼしき商人が,Zealand へ向かう海路の途中にケント海岸のとある農家に立ち寄り,夫人に卵を求めるという状況である.

And one of theym named Sheffelde, a mercer, cam in-to an hows and axed for mete; and specyally axed after eggys. And the goode wyf answerde, that she coude speke no frenshe. And the marchaunt was angry, for he also coude speke no frensche, but wolde have hadde egges, and she understode hym not. And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde have eyren. Then the gode wyf sayd that she understode hym wel. Loo, what sholde a man in thyse dayes wryte, egges or eyren?

[2009-11-06-1]などで触れたとおり,中英語期は方言の時代である.イングランド各地に方言が存在し,いずれの方言も(ロンドンの方言ですら!)標準語としての地位を確立していなかった.したがって,例えば北部出身の話者と南部出身の話者とが会話する場合には,それぞれが自分の方言を丸出しにして話したのであり,時にコミュニケーションが成り立たないこともありえた.上の逸話では「卵」に当たる語の複数形が南部方言では eyren,北部方言では egges だったために,当初,互いにわかり合えなかったくだりが描写されている.

英語本来の複数形を代表しているのは南部の eyren である.古英語では「卵」を表す名詞の単数主格は ǣg という形態だった.これは r-stem と呼ばれるマイナーな屈折タイプに属する中性名詞で,その複数主格形は ǣgru のように -r- が挿入されていた.この点,child / children と同じタイプである ( see [2009-09-19-1], [2009-09-20-1], [2009-12-01-1] ).

初期中英語までは,語尾に -(e)n が付加された異形態も含めて,古英語由来の r をもつ形態がおこなわれていた.しかし,14世紀頃から,古ノルド語由来の硬い <g> をもつ形態が北部・東中部方言に現れ始めた.現代の我々が知っているとおり,最終的に標準英語に生き残ったのは舶来の新参者 eggs のほうであるから歴史はおもしろい.

綴字についても一言.Caxton の生きた時代は,印刷技術が登場した影響で綴字の固定化の兆しの見られる最初期であるが([2010-02-18-1]),上の短い一節のなかでも eggys, egges と語尾に異綴りが見られる.綴字の標準化は,この先150年以上かけて,17世紀から18世紀まで,ゆっくりと進行し,完成してゆくことになる.

(以下,後記:2025/01/19(Sun))

・ heldio 「#183. egges/eyren:卵を巡るキャクストンの有名な逸話」

2010-03-24 Wed

■ #331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語 [french][lexicology][loan_word][etymology][popular_passage][lexical_stratification][animal]

中英語期を中心とするフランス語彙の借用を論じるときに,この話題は外せない.食用の肉のために動物を飼い育てるのはイギリスの一般庶民であるため,動物を表す語はアングロサクソン系の語を用いる.一方で,料理された肉を目にするのは,通常,上流階級のフランス貴族であるため,肉を表す語はフランス系の語を用いる.これに関しては,Sir Walter Scott の小説 Ivanhoe (38) の次の一節が有名である.

. . . when the brute lives, and is in the charge of a Saxon slave, she goes by her Saxon name; but becomes a Norman, and is called pork, when she is carried to the Castle-hall to feast among the nobles . . . .

具体的に例を示すと次のようになる.

| Animal in English | Meat in English | French |

|---|---|---|

| calf | veal | veau |

| deer | venison | venaison |

| fowl | poultry | poulet |

| sheep | mutton | mouton |

| swine ( pig ) | pork, bacon | porc, bacon |

| ox, cow | beef | boeuf |

「豚(肉)」について付け加えると,古英語では「豚」を表す語は swīn だった.pig は中英語で初めて現れた語源不詳の語である.また,後者が一般名称として広く使われるようになったのは19世紀以降である.bacon (豚肉の塩漬け燻製)は古仏語から来ているが,それ自身がゲルマン語からの借用であり,英語の back などと同根である.

・ Scott, Sir Walter. Ivanhoe. Copyright ed. Leipzig: Tauchnitz, 1845.

2010-02-03 Wed

■ #282. Sir William Jones,三点の鋭い指摘 [indo-european][family_tree][comparative_linguistics][popular_passage][sanskrit][history_of_linguistics][jones]

1786年,Sir William Jones (1746--1794) が,自ら設立した the Asiatic Society の設立3周年記念で "On the Hindu's" と題する講演を行った.これが比較言語学の嚆矢となった.Jones の以下の一節は,あまりにも有名である.

The Sanskrit language, whatever be its antiquity, is of a wonderful structure; more perfect than the Greek, more copious than the Latin, and more exquisitely refined than either, yet bearing to both of them a stronger affinity, both in the roots of verbs and the forms of grammar, than could possibly have been produced by accident; so strong indeed, that no philologer could examine them all three, without believing them to have sprung from some common source, which, perhaps, no longer exists. (emphasis added)

Jones の洞察の鋭さは,赤字にした三点に見いだすことができる.

(1) Greek,Latin,その他のヨーロッパ語が互いに言語的に関係しているという発想は当時でも珍しくなかった.ヨーロッパの複数の言語を習得している者であれば,その感覚はおぼろげであれ持ち合わせていただろう.だが,Latin, Greek, Hebrew, Arabic, Persian など東洋の言語を含めた多くの言語(生涯28言語を学習したという!)を修めた Jones は,ヨーロッパ語を飛び越えて Sanskrit までもが Latin, Greek などと言語的に関係しているということを見抜くことができた.現代でも,英語(母語人口で世界第二位)とヒンディー語(第三位)が言語的に関係していることを初めて聞かされれば度肝を抜かれるだろうが,Jones の指摘はそれに近い衝撃を後世に与えた.言語ネットワークの広がりがアジア方面にまで伸長したのである.

(2) Jones 以前にヨーロッパ語どうしの言語的類縁に気づいていた人は,主に語彙の類縁のことを話題にしていた.ところが,Jones は文法(特に形態論)どうしも似ているのだと主張した.言語ネットワークに深みという新たな次元が付け加えられたのである.

(3) Jones 以前には,関連する諸言語の生みの親は現存するいずれかの言語だろうと想像されていた.しかし,Jones は鋭い直感をもって,親言語はすでに死んで失われているだろうと踏んだ.この発想は,言語ネットワークが時間という次元を含む立体的なものであり,消える言語もあれば派生して生まれる言語もあるということを前提としていなければ生じ得ない.

Jones 自身はこの発見がそれほどの大発見だとは思っていなかったようで,その後,みずから実証しようと試みた形跡もない.Jones の頭の中に印欧語の系統図([2009-06-17-1])のひな形のようなものがあったとは考えにくいが,彼の広い見識に基づく直感は結果として正しかったことになる.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow