2018-05-23 Wed

■ #3313. 言語変化の速度について再再考 [speed_of_change][prescriptivism][causation][sociolinguistics][japanese][link][monitoring]

昨日の記事「#3312. 言語における基層と表層」 ([2018-05-22-1]) で,言語の「基層」を構成する要素として,文法,音声・音韻,基礎語彙を挙げた.言語変化の速度を考察する際に,考察対象を基層における言語変化に限定するならば,一般に時代がくだるほど速度が鈍くなるということはあるかもしれない.日本語史の事情から敷衍して,野村 (14--15) が次のように述べている.

一般に近代化の進んだ社会では,特別な外部的要因がない限り,言語の変化は,近代やそれに近い時代において鈍いと筆者は考えている.なぜか.近代では書き言葉の(文字の)普及が進んでいるからである.

すでに述べたように,話し言葉は話した瞬間に消えてしまう.言葉をとどめる手段がない.話し言葉だけの社会では,歌謡などの暗誦でもない限り,過去の言葉は全く残らない.言葉を振り返ることは不可能なのである.これに対して,書き言葉は長期にわたって残存する.それを真似し続けることによって次第に文語体が生じるのだが,口語体であっても繰り返し筆記が行なわれれば,それは話し言葉の変化をおしとどめる方向の力として働くだろう.日本社会でも,古代よりは中世,中世よりは近世,近世よりは近代の方が読み書き能力が広く普及しているに違いない.そこで,より近代に近い社会の方が言語の基層における変化は乏しいのである.もちろん細かな言語変化はより近代に近い時代においてもたくさん生じているし,また,方言はふつう書きとどめられない.だから,地域地域で大きな変異が生ずるということも,大いにありうる.

時代が下るにつれて,基層における言語変化が乏しくなるという説は,間に2段階くらいの論理のクッションを入れるとわかりやすいだろう.つまり,一般に時代が下るにつれて識字率が上がる,識字率が上がるにつれて言語の規範意識が育つ,言語の規範意識が育つにつれて話し言葉の変化も抑制される,ということだ.これは妥当といえば妥当な見解だが,引用でも示唆されているとおり,主に標準変種についての説である.非標準変種において同じ議論が成り立つのかはわからないし,考察対象を基層でなく表層まで広げるとどうなるのかも検討してみる必要がある.

言語変化の速度 (speed_of_change) の問題や規範主義 (prescriptivism) が言語変化を遅らせるという議論については,以下を含む多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,ご参照ください.monitoring の各記事も参照.

・ 「#386. 現代英語に起こっている変化は大きいか小さいか」 ([2010-05-18-1])

・ 「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1])

・ 「#622. 現代英語の文法変化は統計的・文体的な問題」 ([2011-01-09-1])

・ 「#753. なぜ宗教の言語は古めかしいか」 ([2011-05-20-1])

・ 「#795. インターネット時代は言語変化の回転率の最も速い時代」 ([2011-07-01-1])

・ 「#1430. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (2)」 ([2013-03-27-1])

・ 「#1874. 高頻度語の語義の保守性」 ([2014-06-14-1])

・ 「#2417. 文字の保守性と秘匿性」 ([2015-12-09-1])

・ 「#2631. Curzan 曰く「言語は川であり,規範主義は堤防である」」 ([2016-07-10-1])

・ 「#2641. 言語変化の速度について再考」 ([2016-07-20-1])

・ 「#2670. 書き言葉の保守性について」 ([2016-08-18-1])

・ 「#2756. 読み書き能力は言語変化の速度を緩めるか?」 ([2016-11-12-1])

・ 「#3002. 英語史が近代英語期で止まってしまったかのように見える理由 (3)」 ([2017-07-16-1])

・ 野村 剛史 『話し言葉の日本史』 吉川弘文館,2011年.

2018-05-14 Mon

■ #3304. 規範主義が18世紀に成長した背景,2点 [language_myth][prescriptive_grammar][sociolinguistics][johnson][latin]

18世紀のイギリスに規範主義が急成長した背景について,「#1244. なぜ規範主義が18世紀に急成長したか」 ([2012-09-22-1]) をはじめとして prescriptive_grammar の記事で取り上げてきた. Aitchison は,2つの強力な社会的要因が背景にあり,規範主義がある種の宗教的な教義にまで持ち上げられたのだと考えている.その2つとは,"The first was a long-standing admiration for Latin, and the second was powerful class snobbery" (10) である.

まず,ラテン語への憧憬について.西洋においてラテン語の威信がすこぶる高かったのは,中世においてキリスト教会の言語であったこと,そして近代のルネサンス以降に学問の言語となったことによる.すでにラテン語は誰の母語でもなかったにもかかわらず,キケロのように正しく書くことが理想とされ,ラテン語教育が盛んに行なわれてきた.Ben Jonson をして "queen of tongues" と言わしめたほどであり,実際,俗語の文法が記述される際には,常にラテン語文法がモデルとされた.

このラテン語の圧倒的な威信ゆえに,俗語に対して3つの態度が生じることになった.1つは,言語には固定された正しい語法があるものだという考え方である.もう1つには,ラテン語が専ら書き言葉だったために,話し言葉に対する書き言葉の優越という見方が生じた.最後に,ラテン語が豊富な屈折を示す言語であるために,屈折を大幅に失った英語のような言語は堕落した言語であるという神話が生まれた.

規範主義が18世紀に成長した2点目の要因は,上流崇拝である.Samuel Johnson がその典型である.Johnson は Dictionary を編纂する際に,上流階級や最良の著者が書き言葉で用いる語(法)を選んで採用し,逆に下層の人々の話し言葉についてはこき下ろした.

このような時代背景のなかで発展した規範主義と規範文法は,その後の19世紀,20世紀,21世紀にも受け継がれ,いまなお健在である.一つの神話の誕生と成長といってよいだろう.

・ Aitchison, Jean. Language Change: Progress or Decay. 4th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2018-04-20 Fri

■ #3280. アメリカにおける民族・言語的不寛容さの歴史的背景 [sociolinguistics][aave][ame_bre][ame][linguistic_ideology][ethnic_group]

英語を主たる言語としてもつ英米両国では,言語における標準 (standard) のあり方,捉え方が異なる.イギリスでは標準的な発音である RP が存在するが,アメリカでは RP に相当する威信をもった唯一の発音は存在しない.また,標準と非標準を区別する軸は,イギリスでは階級 (class) といえるが,アメリカでは民族 (ethnic group) にあるというべきだろう.この違いは両国の歴史と社会を反映している.以下,18世紀以降のアメリカの状況を Milroy and Milroy (157--58) に従って略述しよう.

アメリカが民族という観点から,例えば AAVE のような英語変種に対する寛容さを欠いているのには歴史的な背景がある.18世紀までは,アメリカにも言語的寛容さが相当に存在した.国家としても話者個人としても多言語使用は日常の事実だったのだ.まず第1に,18世紀のアメリカには,植民地支配の伝統を有する支配的な言語として,英語のほかにスペイン語やフランス語も存在していた.南西部やフロリダでは,むしろ英語よりもスペイン語を使用する伝統のほうが長かったし,フランス語の伝統を受け継ぐ地域もあった.第2に,初期の植民者たちはアメリカ先住民の諸言語に触れてきた経緯があり,ほかにドイツ人植民者のコミュニティなどもあった.アメリカにおける全体的な英語の優勢は疑い得なかったとしても,多言語使用は社会的に忌避される対象などではなかった.

ところが,19世紀が進むにつれ多言語使用に対する寛容さが失われ,英語偏重思想が表出してきた.これには,世紀半ばのゴールド・ラッシュが1つの契機となっている.中国人移民が金を求めて西部に大量に入ったことにより,強烈な排外思想が生まれた.1848年のアメリカによる南西部メキシコ領の併合も,スペイン語話者に対する英語話者の優勢思想を惹起し,民族・言語的不寛容を増長させるのに一役買った.そして,1878年にはカリフォルニアが初の「英語オンリー」の州となった.このような不寛容な社会風潮のなかで,先住民の諸言語も軽視されるようになった.最後に,奴隷貿易や南北戦争の歴史も,当然ながらこの民族・言語的不寛容の重要な背景をなしている.その後,この風潮は,20世紀,そして21世紀にも受け継がれている.

Milroy and Milroy (160) のまとめに耳を傾けよう.

In the US, bitter divisions created by slavery and the Civil War shaped a language ideology focused on racial discrimination rather than on the class distinctions characteristic of an older monarchical society like Britain which continue to shape language attitudes. Also salient in the US was perceived pressure from large numbers of non-English speakers, from both long-established communities (such as Spanish speakers in the South-West) and successive waves of immigrants. This gave rise in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries to policies and attitudes which promoted Anglo-conformity. To this day these are embodied in a version of the standard language ideology which has the effect of discriminating against speakers of languages other than English --- again an ideology quite different from that characteristic of Britain.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 4th ed. London and New York: Routledge, 2012.

2018-04-08 Sun

■ #3268. 談話標識のライフサイクルは短い [discourse_marker][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][language_change][intensifier][euphemism][sociolinguistics][speed_of_change]

言語には変化の回転が速い領域というものがある.「#992. 強意語と「限界効用逓減の法則」」 ([2012-01-14-1]) や「#1219. 強意語はなぜ種類が豊富か」 ([2012-08-28-1]) で述べたように,強意語 (intensifier) や,タブー表現 (taboo) の響きをやわらげる婉曲表現 (euphemism) が次々と生まれては消えることは,よく知られている.視点を変えれば,これらの表現はライフサイクルが短いということになろう.

同様に,昨日の記事「#3267. 談話標識とその形成経路」 ([2018-04-07-1]) で取り上げた談話標識も,比較的ライフサイクルが短いとされている.実際,談話標識は歴史的に新しい表現が生まれては消える過程を繰り返してきた.昨日の記事でも示したように,談話標識は特に話し言葉において頻度が高いこと,そして種々の源から形成されうることが,背景にあるのだろう.この点について Lewis (909) が次のように述べている.

Discourse markers are known for their frequent renewal. Particularly subject to sociolinguistic factors and fashion, they tend to be "caught" easily, spreading quickly among social networks. Choice of markers therefore can reflect age, social position, and so on. Discourse markers date quickly: many of the most frequent discourse markers and connectives of the 20th century arose only in the 18th or 19th century, including of course, after all, still, I say.

ライフサイクルが速いといっても数世代以上の時間がかかるようであり,強意語や婉曲語法に見られるライフサイクルほど速いわけではなさそうだ.しかし,そのうちにきっと変わるにちがいないと言わしめるほどには「規則的な」言語変化の一種とみなせそうだ.また,引用の最初にあるように,談話標識に話者の世代を特徴づける性質があるというのも興味深い.歴史社会言語学的な観察対象になり得ることを意味するからだ.談話標識の流行としての側面は,もっと注目してもよいだろう.

・ Lewis, Diana M. "Late Modern English: Pragmatics and Discourse" Chapter 56 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 901--15.

2018-04-04 Wed

■ #3264. Saussurian Paradox [saussure][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][idiolect][methodology]

標題の「ソシュールのパラドックス」について,「#3245. idiolect」 ([2018-03-16-1]) で触れた通りだが,改めて『新英語学辞典』の "sociolinguistics" の項 (1124) の記述を読んでみよう,

構造言語学では,言語単位の対立関係に基づいて成立している構造を明らかにすることが中心的な課題であり,そのために言語を共時的な静態においてとらえ,資料はできるだけ等質的であることが必要であると考えた.その裏にある言語観は,言語はその理想的な姿においては単一の構造体である (monolithic) とするものである.その単一体を求めるために,個人的なゆれ,場面ごとに変容する部分は自由変異,あるいは乱れ・逸脱として切り捨てた.目標はある言語社会に共通の構造体(=ラング)を求めることでありながら,資料の等質性を求めて,ついには個人言語 (idiolect) を対象とするという状態に至った.Labov (1972a) はこれを 'Saussurian Paradox' と呼ぶ.構造の単一性を求めて言語は実際の使用場面から切り離され,単一の 'ideal speaker-hearer' の言語能力を求めるのだとして,資料は高度に理想化され,現実から遊離した形に整えられた.

言語学史的には,ソシュールの創始した構造言語学は,言語構造が等質的であり単一的であることを意識的に前提とすることで,揺れを考慮しなくてよいという方法論上の正当性を確保したのだろうと考えている.実際には等質的でもなければ単一的でもないし,揺れも存在する.しかし,あえて切り捨てて前進するという行き方もあるだろうと.その行き方は確かに方法論としては悪いことではないだろう.しかし,言語の variation や variability は,あくまで脇に置いたのであって,存在しないわけではない.

理論的理想と実践的現実は常に背反する.理論を扱っている場合には,現実から遊離しすぎていないだろうかという問いかけを,実践的に研究している場合には,あまりに小さな揺れにこだわってはいないかという自問が必要だろう.

関連して「#2202. langue と parole の対比」 ([2015-05-08-1]) を参照.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄 監修 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1987年.

2018-04-01 Sun

■ #3261. ドイツ国歌の「父なる祖国」を巡るジェンダー問題 [gender][sociolinguistics][political_correctness][grimms_law][verners_law]

ドイツ国歌の歌詞にある Vaterland (父なる祖国)が男性バイアスの用語なので,Heimatland (故郷の国)に変更しようという political_correctness の提案がドイツ国内でなされている.ドイツ政府による男女共同参画の推進を担当する女性の政治活動家が提案したもので,目下,物議を醸している.ジェンダーについて中立な言葉遣いが時勢に合っているからという理由での提案だが,保守系の政治家は「やりすぎだ」「これを変えるなら『母語』という言葉も使えない」などと反発している.メルケル首相も変更は不要という立場のようだ.

ドイツ国歌は,オーストリアの作曲家ハイドンの曲に対して1841年に歌詞づけしたもので,国歌としては旧西ドイツから東西統一後のドイツへの引き継がれた.国歌の歌詞におけるジェンダーの問題は最近オーストリアやカナダでも起こっており,そこでは中立的な表現に置き換えられたという経緯がある.これらの先例を受けての,ドイツでの論争という次第である.

英語でも「祖国,故国」を表わす語として fatherland という言い方がある.motherland という言い方もあるが,PC の観点からはジェンダーについて中立な homeland, native country, home が用いられることが多くなっているという.しかし,借用語の patriot (愛国者),patriotism (愛国心)などでは語幹にラテン語で「父」を意味する pater が含まれており,発想としては fatherland と酷似するのだが,これについては特にジェンダー論争が起こっているという話しは聞かない.借用語では,語幹の「父」の意味が直接には感じ取られにくいからだろうか.

ラテン語 pater と英語 father は語源的には同根だが,その関係を詳しく理解しようと思えば「グリムの法則」 (grimms_law) や「ヴェルネルの法則」 (verners_law) の知識が必要となる.それには,「#2277. 「行く」の意味の repair」 ([2015-07-22-1]),「#102. hundred とグリムの法則」 ([2009-08-07-1]),「#480. father とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2010-08-20-1]),「#2297. 英語 flow とラテン語 fluere」 ([2015-08-11-1]) 辺りの記事をどうぞ.

2018-03-21 Wed

■ #3250. 現代ロシアの諸民族が抱える「ロシアのくびき」問題 [language_planning][linguistic_right][sociolinguistics][altaic][map][russian]

ロシアではプーチン大統領の4期目が決まり,引き続き強権政治が展開されることが見込まれている.2月28日の読売新聞朝刊の8面に「多民族ロシアのくびき」という見出しの記事が掲載されていた.プーチンは100以上の民族を抱える大国を運営するにあたり「国家の安定」と「社会の団結」を強調しているが,その主張を言語的に反映させる政策として,国家,民族の共通の言語としてのロシア語を推進する方針を打ち出している.裏返していえば,少数民族の言語を軽視する政策である.

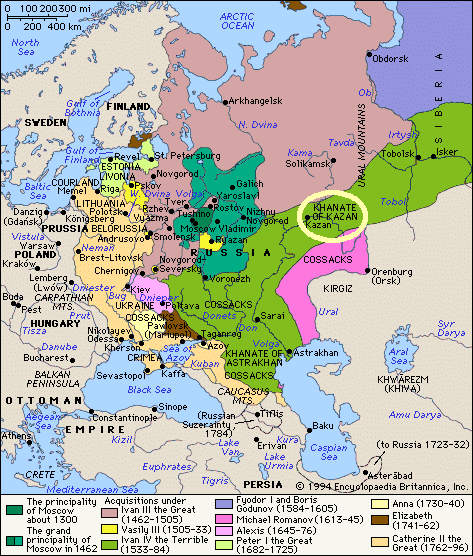

新聞記事で取り上げられていたのは,モスクワの東方約800キロほど,ウラル山脈の西のボルガ川中流域に位置するタタルスタン共和国におけるタタール語 (TaTar, Tartar) を巡る問題である.タタール語は,アルタイ語族の西チュルク語派に属する言語で,中世以来,この地域に根付いてきた(「#1548. アルタイ語族」 ([2013-07-23-1]) を参照).歴史的には,モンゴル帝国の流れを汲むキプチャク・ハン国の後裔となったカザン・ハン国が15--16世紀に栄え,首都のカザニを中心にイスラム文化が花咲いた.ロシア人の立場から見れば,1237--1480年まで「タタールのくびき」のもとで苛烈な支配を受け,その後1552年にイワン雷帝が現われてこの地を征服したということになる.ソ連時代にはタタール自治共和国として存在し,現在はロシア連邦に属する民族共和国の1つとして存在する.タタルスタン共和国の現在の人口は約388万人で,そのうちタタール語を話すタタール人が53%,ロシア人が40%を占める(ロシア全体としてもタタール人はロシア人に次いで多い民族である).共和国ではロシア語とタタール語が公用語となっている.

義務教育学校では,タタール語も必修科目とされているが,近年は当局が脱必修化の圧力をかけてきているという.これに反発する保護者や住民も多く,当局のタタール語軽視はタタール人の尊厳を傷つけていると非難している.言語教育問題が社会問題となっている事例である.

タタール語については,Ethnologue よりこちらの説明やこちらの地図も参照.

2018-03-17 Sat

■ #3246. 制限コードと精密コード [sociolinguistics][terminology][context][style]

標題は,現在でも社会言語学においてたまに出会う用語・概念である.制限コード (restricted code) と洗練コード (elaborated code) は,対立する2つの言語使用形態を表わす.制限コードは,比較的少ない語彙や単純な文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の高い言葉遣いである.一方,精密コードは,豊富な語彙と洗練された文法構造を用いた,文脈依存性の低い言葉遣いである.極端ではあるが,子供の用いるインフォーマルな話し言葉と,大人の用いるフォーマルな書き言葉の対立をイメージすればよい.

この用語がある種の問題を帯びたのは,用語の導入者であるイギリスの社会言語学者 Basil Bernstein が,異なる階級の子供たちの言葉遣いを区別するのにそれを用いたからである.中流階級の子供は両コードを使えるが,労働者階級の子供は制限コードしか使えないという点を巡って,それが各階級の言語習慣の問題なのか,あるいは知性そのものの問題なのかという議論が持ち上がり,教育上の論争に発展した.現在では知性とは関係ないとされているものの,用語のインパクトは強く,いまなお健在である.

Crystal の用語集より,"restricted" と "elaborated" の説明をみておこう.

restricted (adj.) A term used by British sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social roles, the other being elaborated. Restricted code was thought to be used in relatively informal situations, stressing the speaker's membership of a group, was very reliant on context for its meaningfulness (e.g. there would be several shared expectations and assumptions between the speakers), and lacked stylistic range. Linguistically, it was highly predictable, with a relatively high proportion of such features as pronouns, tag questions, and use of gestures and intonation to convey meaning. Elaborated code, by contrast, was thought to lack these features. The correlation of restricted code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to this code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

elaborated (adj.) A term used by the sociologist Basil Bernstein (1924--2000) to refer to one of two varieties (or codes) of language use, introduced as part of a general theory of the nature of social systems and social rules, the other being restricted. Elaborated code was said to be used in relatively formal, educated situations; not to be reliant for its meaningfulness on extralinguistic context (such as gestures or shared beliefs); and to permit speakers to be individually creative in their expression, and to use a range of linguistic alternatives. It was said to be characterized linguistically by a relatively high proportion of such features as subordinate clauses, adjectives, the pronoun I and passives. Restricted code, by contrast, was said to lack these features. The correlation of elaborated code with certain types of social-class background, and its role in educational settings (e.g. whether children used to a restricted code will succeed in schools where elaborated code is the norm --- and what should be done in such cases), brought this theory considerable publicity and controversy, and the distinction has since been reinterpreted in various ways.

英語史上,制限コードに関連して取り上げられ得る話題は,「#3043. 後期近代英語期の識字率」 ([2017-08-26-1]) で見たような識字率の問題だろう.両コードの区別を念頭に,書き言葉というメディアと識字教育の歴史を再検討してみるとおもしろいかもしれない.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-09 Fri

■ #3238. 言語交替 [language_shift][language_death][bilingualism][diglossia][terminology][sociolinguistics][irish][terminology]

本ブログでは,言語交替 (language_shift) の話題を何度か取り上げてきたが,今回は原点に戻って定義を考えてみよう.Trudgill と Crystal の用語集によれば,それぞれ次のようにある.

language shift The opposite of language maintenance. The process whereby a community (often a linguistic minority) gradually abandons its original language and, via a (sometimes lengthy) stage of bilingualism, shifts to another language. For example, between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, Ireland shifted from being almost entirely Irish-speaking to being almost entirely English-speaking. Shift most often takes place gradually, and domain by domain, with the original language being retained longest in informal family-type contexts. The ultimate end-point of language shift is language death. The process of language shift may be accompanied by certain interesting linguistic developments such as reduction and simplification. (Trudgill)

language shift A term used in sociolinguistics to refer to the gradual or sudden move from the use of one language to another, either by an individual or by a group. It is particularly found among second- and third-generation immigrants, who often lose their attachment to their ancestral language, faced with the pressure to communicate in the language of the host country. Language shift may also be actively encouraged by the government policy of the host country. (Crystal)

言語交替は個人や集団に突然起こることもあるが,近代アイルランドの例で示されているとおり,数世代をかけて,ある程度ゆっくりと進むことが多い.関連して,言語交替はしばしば bilingualism の段階を経由するともあるが,ときにそれが制度化して diglossia の状態を生み出す場合もあることに触れておこう.

また,言語交替は移民の間で生じやすいことも触れられているが,敷衍して言えば,人々が移動するところに言語交替は起こりやすいということだろう(「#3065. 都市化,疫病,言語交替」 ([2017-09-17-1])).

アイルランドで歴史的に起こった(あるいは今も続いている)言語交替については,「#2798. 嶋田 珠巳 『英語という選択 アイルランドの今』 岩波書店,2016年.」 ([2016-12-24-1]),「#1715. Ireland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-06-1]),「#2803. アイルランド語の話者人口と使用地域」 ([2016-12-29-1]),「#2804. アイルランドにみえる母語と母国語のねじれ現象」 ([2016-12-30-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

・ Crystal, David, ed. A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2008. 295--96.

2018-03-05 Mon

■ #3234. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) の春期セミナーで標準英語の発達について話しました [notice][academic_conference][standardisation][slide][ame_bre][etymological_respelling][3sp][sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][link]

[2018-02-12-1]の記事で通知したように,昨日3月4日に桜美林大学四谷キャンパスにて「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC)の春期セミナーの一環として,「『良い英語』としての標準英語の発達―語彙,綴字,文法を通時的・複線的に追う―」と題するお話しをさせていただきました.足を運んでくださった方々,主催者の方々に,御礼申し上げます.私にとっても英語の標準化について考え直すよい機会となりました.

スライド資料を用いて話し,その資料は上記の研究会ホームページ上に置かせてもらいましたが,資料へのリンクをこちらからも張っておきます.スライド内からは本ブログ内外へ多数のリンクを張り巡らせていますので,リンク集としてもどうぞ.

1. 「言語と人間」研究会 (HLC) 第43回春季セミナー 「ことばにとって『良さ』とは何か」「良い英語」としての標準英語の発達--- 語彙,綴字,文法を通時的・複線的に追う---

2. 序論:標準英語を相対化する視点

3. 標準英語 (Standard English) とは?

4. 標準英語=「良い英語」

5. 標準英語を相対化する視点の出現

6. 言語学の様々な分野と方法論の発達

7. 20世紀後半?21世紀初頭の言語学の関心の推移

8. 標準英語の形成の歴史

9. 標準語に軸足をおいた Blake の英語史時代区分

10. 英語の標準化サイクル

11. 部門別の標準形成の概要

12. Milroy and Milroy による標準化の7段階

13. Haugen による標準化の4段階

14. ケース・スタディ (1) 語彙 -- autumn vs fall

15. 両語の歴史

16. ケース・スタディ (2) 綴字 -- 語源的綴字 (etymological spelling)

17. debt の場合

18. 語源的綴字の例

19. フランス語でも語源的スペリングが・・・

20. その後の発音の「追随」:fault の場合

21. 語源的綴字が出現した歴史的背景

22. EEBO Corpus で目下調査中

23. ケース・スタディ (3) 文法 -- 3単現の -s

24. 古英語の動詞の屈折:lufian (to love) の場合

25. 中英語の屈折

26. 中英語から初期近代英語にかけての諸問題

27. 諸問題の意義

28. 標準化と3単現の -s

29. 3つのケーススタディを振り返って

30. 結論

31. 主要参考文献

2018-03-03 Sat

■ #3232. 理想化された抽象的な変種としての標準○○語 [standardisation][linguistic_ideology][sociolinguistics]

標準英語の歴史に焦点を当てた論文集の巻頭で,Milroy (11) が非常にうまい言い方で標準○○語というものの抽象性について述べている.

It has been observed (Coulmas 1992: 175) that 'traditionally most languages have been studied and described as if they were standard languages'. This is largely true of historical descriptions of English, and I am concerned in this paper with the effects of the ideology of standardisation (Milroy and Milroy 1991: 22--3) on scholars who have worked on the history of English. It seems to me that these effects have been so powerful in the past that the picture of language history that has been handed down to us is a partly false picture --- one in which the history of the language as a whole is very largely the story of the development of modern Standard English and not of its manifold varieties. This tendency has been so strong that traditional histories of English can themselves be seen as constituting part of the standard ideology --- that part of the ideology that confers legitimacy and historical depth on a language, or --- more precisely --- on what is held at some particular time to be the most important variety of a language.

In the present account, the standard language will not be treated as a definable variety of a language on a par with other varieties. The standard is not seen as part of the speech community in precisely the same sense that vernaculars can be said to exist in communities. Following Haugen (1966), standardisation is viewed as a process that is in some sense always in progress.

標準○○語とは静的な存在物ではなく,動的で流体のようなものである.標準化という動的な過程を,静的なものへとマッピングした架空の抽象的な言語変種に近いということだ.もちろん,標準○○語に限らず,あらゆる言語変種がフィクションであるとはいえる(cf. 「#1373. variety とは何か」 ([2013-01-29-1]),「#415. All linguistic varieties are fictions」 ([2010-06-16-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]),「#2265. 言語変種とは言語変化の経路をも決定しうるフィクションである」 ([2015-07-10-1])).しかし,標準○○語は,標準を神聖視するイデオロギーに支えられて,重層的なフィクション――フィクションのフィクション――になりやすい代物であるのかもしれない.「#1396. "Standard English" とは何か」 ([2013-02-21-1]) という問題に迫るにも,幾重もの表皮をはぎ取らなければならないのだろう.

・ Milroy, Jim. "Historical Description and the Ideology of the Standard Language." The Development of Standard English, 1300--1800. Ed. Laura Wright. Cambridge: CUP, 2000. 11--28.

・ Coulmas, F. Language and Economy. Oxford: Blackwell, 1992.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

・ Haugen, Einar. "Dialect, Language, Nation." American Anthropologist. 68 (1966): 922--35.

2018-02-21 Wed

■ #3222. 第2回 HiSoPra* 研究会で英語史における標準化について話します [notice][academic_conference][historical_pragmatics][sociolinguistics][standardisation][hisopra]

昨年の3月14日に立ち上げられ,学習院大学で開催された歴史社会言語学・歴史語用論の研究会 HiSoPra* (= HIstorical SOciolinguistics and PRAgmatics) の第2回が,来る3月13日に同じく学習院大学にて開かれる予定です.プログラム等の詳細はこちらの案内 (PDF)をご覧ください.

昨年の第1回研究会については,私も討論に参加させていただいた経緯から,本ブログ上で「#2883. HiSoPra* に参加して (1)」 ([2017-03-19-1]),「#2884. HiSoPra* に参加して (2)」 ([2017-03-20-1]) にて会の様子を報告しました.今度の第2回でも,「スタンダードの形成 ―個別言語の歴史を対照して見えてくるもの☆」と題するシンポジウムで,英語の標準化の過程に関して少しお話しさせていただくことになりました.諸言語のスタンダード形成の歴史を比較対照して,フロアの方々と議論しながら知見を深め合うという趣旨です.議論に先立って,日本語について東京大学名誉教授の野村剛史先生に講演していただき,その後を受ける形で堀田が英語について,そして学習院大学の高田博行先生がドイツ語について,話題を提供するという構成になっています.3言語(プラスα)における標準化の過程を,いわば歴史対照言語学的にみるという試みですが,企画の話し合いの段階から,実に興味深い言語間の異同ポイントが複数あると判明し,本番が楽しみです.その他,研究発表や研究報告も予定されています.

英語の標準化に関する話題は,本ブログでも standardisation の諸記事で書きためてきました.今回の企画を契機に,改めて考えて行く予定です.

2018-02-08 Thu

■ #3209. 言語標準化の7つの側面 [standardisation][sociolinguistics][terminology][language_planning][reestablishment_of_english][spelling_reform][genbunicchi]

言語の標準化の問題を考えるに当たって,1つ枠組みを紹介しておきたい.Milroy and Milroy (27) にとって,standardisation とは言語において任意の変異可能性が抑制されることにほかならず,その過程には7つの段階が認められるという.selection, acceptance, diffusion, maintenance, elaboration of function, codification, prescription である.これは古典的な「#2745. Haugen の言語標準化の4段階 (2)」 ([2016-11-01-1]) に基づいて,さらに精密化したものとみることができる.Haugen は,selection, codification, elaboration, acceptance の4段階を区別していた.

Milroy and Milroy の7段階という枠組みを用いて標準英語の形成を歴史的に分析・解説したものとしては,Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade の論考が優れている.そこではもっぱら現代標準英語の発達の歴史が扱われているが,同じ方法で英語史における大小様々な「標準化」を切ることができるだろうと述べている.かぎ括弧つきの「標準化」は,何らかの意味で個人や集団による人為的な要素が認められる言語改革風の営みを指している.具体的には,10世紀のアルフレッド大王による土着語たる古英語の公的な採用(ラテン語に代わって)や,Chaucer 以降の書き言葉としての英語の採用(フランス語やラテン語に代わって)や,12世紀末の Orm の綴字改革や,19世紀の William Barnes による母方言たる Dorset dialect を重用する試みや,アメリカ独立革命期以降の Noah Webster による「アメリカ語」普及の努力などを含む (Nevalainen and Tieken-Boon van Ostade 273) .互いに質や規模は異なるものの,これらのちょっとした言語計画 (language_planning) というべきものを,「標準化」の試みの事例として Milroy and Milroy 流の枠組みで切ってしまおうという発想は,斬新である.

日本語史でいえば,現代標準語の形成という中心的な話題のみならず,仮名遣いの変遷,言文一致運動,常用漢字問題,ローマ字問題などの様々な事例も,広い意味での標準化の問題としてカテゴライズされ得るということになろう.

・ Milroy, Lesley and James Milroy. Authority in Language: Investigating Language Prescription and Standardisation. 2nd ed. London and New York: Routledge, 1991.

・ Nevalainen, Terttu and Ingrid Tieken-Boon van Ostade. "Standardisation." Chapter 5 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 271--311.

2018-02-06 Tue

■ #3207. 標準英語と言語の標準化に関するいくつかの術語 [terminology][sociolinguistics][standardisation][koine][dialect_levelling][language_planning][variety]

このところ,英語の標準化 (standardisation) の歴史のみならず,言語の標準化について一般的に考える機会を多くもっている.この問題に関連する術語と概念を整理しようと,社会言語学の用語集 (Trudgill) を開いてみた.そこから集めたいくつかの術語とその定義・説明を,備忘のために記しておきたい.

まずは,英語に関してずばり "Standard English" という用語から(「#1396. "Standard English" とは何か」 ([2013-02-21-1]),「#2116. 「英語」の虚構性と曖昧性」 ([2015-02-11-1]) も参照).

Standard English The dialect of English which is normally used in writing, is spoken by educated native speakers, and is taught to non-native speakers studying the language. There is no single accent associated with this dialect, but the lexicon and grammar of the dialect have been subject to codification in numerous dictionaries and grammars of the English language. Standard English is a polycentric standard variety, with English, Scottish, American, Australian and other standard varieties differing somewhat from one another. All other dialects can be referred to collectively as nonstandard English.

ここで使われている "polycentric" という用語については,「#2384. polycentric language」 ([2015-11-06-1]) と「#2402. polycentric language (2)」 ([2015-11-24-1]) も参照.

次に,"standardisation" という用語から芋づる式にいくつかの用語をたどってみた.

standardisation The process by which a particular variety of a language is subject to language determination, codification and stabilisation. These processes, which lead to the development of a standard language, may be the result of deliberate language planning activities, as with the standardisation of Indonesia, or not, as with the standardisation of English.

status planning [≒language determination] In language planning, status planning refers to decisions which have to be taken concerning the selection of particular languages or varieties of language for particular purposes in the society or nation in question. Decisions about which language or languages are to be the national or official languages of particular nation-states are among the more important of status planning issues. Status planning is often contrasted with corpus planning or language development. In the use of most writers, status planning is not significantly different from language determination.

codification The process whereby a variety of a language, often as part of a standardisation process, acquires a publicly recognised and fixed form in which norms are laid down for 'correct' usage as far as grammar, vocabulary, spelling and perhaps pronunciation are concerned. This codification can take place over time without involvement of official bodies, as happened with Standard English, or it can take place quite rapidly, as a result of conscious decisions by governmental or other official planning agencies, as happened with Swahili in Tanzania. The results of codification are usually enshrined in dictionaries and grammar books, as well as, sometimes, in government publications.

stabilisation A process whereby a formerly diffuse language variety that has been in a state of flux undergoes focusing . . . and takes on a more fixed and stable form that is shared by all its speakers. Pidginised jargons become pidgins through the process of stabilisation. Dialect mixtures may become koinés as a result of stabilisation. Stabilisation is also a component of language standardisation.

focused According to a typology of language varieties developed by the British sociolinguist Robert B. LePage, some language communities and thus language varieties are relatively more diffuse, while others are relatively more focused. Any speech act performed by an individual constitutes an act of identity. If only a narrow range of identities is available for enactment in a speech community, that community can be regarded as focused. Focused linguistic communities tend to be those where considerable standardisation and codification have taken place, where there is a high degree of agreement about norms of usage, where speakers tend to show concern for 'purity' and marking their language variety off from other varieties, and where everyone agrees about what the language is called. European language communities tend to be heavily focused. LePage points out that notions such as admixture, code-mixing, code-switching, semilingualism and multilingualism depend on a focused-language-centred point of view of the separate status of language varieties.

diffuse According to a typology of language varieties developed by the British sociolinguist Robert B. LePage, a characteristic of certain language communities, and thus language varieties. Some communities are relatively more diffuse, while others are relatively more focused. Any speech act performed by an individual constitutes an act of identity. If a wide range of identities is available for enactment in a speech community, that community can be regarded as diffuse. Diffuse linguistic communities tend to be those where little standardisation or codification have taken place, where there is relatively little agreement about norms of usage, where speakers show little concern for marking off their language variety from other varieties, and where they may accord relatively little importance even to what their language is called.

最後に挙げた2つ "focused" と "diffuse" は言語共同体や言語変種について用いられる対義の形容詞で,実に便利な概念だと感心した.光の反射の比喩だろうか,集中と散乱という直感的な表現で,標準化の程度の高低を指している.英語史の文脈でいえば,中英語は a diffuse variety であり,(近)現代英語や後期古英語は focused varieties であると概ね表現できる."focused" のなかでも程度があり,程度の高いものを "fixed",低いものを狭い意味での "focused" とするならば,(近)現代英語は前者,後期古英語は後者と表現できるだろう.fixed と focused の区別については,「#929. 中英語後期,イングランド中部方言が標準語の基盤となった理由」 ([2011-11-12-1]) も参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

2018-02-03 Sat

■ #3204. 歴史社会言語学と歴史語用論の合流 [sociolinguistics][history_of_linguistics][historical_pragmatics][history_of_linguistics][hisopra]

「#3198. 語用論の2潮流としての Anglo-American 対 European Continental」 ([2018-01-28-1]),「#3203. 文献学と歴史語用論は何が異なるか?」 ([2018-02-02-1]) の記事で,言語学史的な観点から,近年発展の著しい歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) について考えた.関連の深い学問分野として歴史社会言語学 (historical sociolinguistics) も同様に成長してきており,扱う問題の種類によっては,事実上,2つの分野は合流しているといってよい.名前はその分長くなるが,歴史社会語用論 (historical sociopragmatics) という分野が育ってきているということだ.略して "HiSoPra" ということで,1年ほど前に日本でもこの名前の研究会が開かれた(「#2883. HiSoPra* に参加して (1)」 ([2017-03-19-1]),「#2884. HiSoPra* に参加して (2)」 ([2017-03-20-1]) を参照).

この20--30年ほどの間の「歴史社会言語学+歴史語用論=歴史社会語用論」という学問領域の進展について,Taavitsainen (1469) が鮮やかに記述している1節があるので,引用しよう.

Historical sociolinguistics was launched more than a decade earlier than historical pragmatics . . . . The focus is on the extent to which change in language is conditioned by the social factors identified as characterizing the dataset. In recent years, historical pragmatics and historical sociolinguistics have converged. If for example a recent definition of pragmatics by Mey . . . is taken as the point of departure, "[p]ragmatics studies the use of language in human communication as determined by the conditions of society", the difference between historical sociolinguistics and pragmatics disappears altogether, and pragmatics is always "socio-" in the European broad view of pragmatics. This reflects the European tradition; in the Anglo-American the difference is still valid. The convergence is also acknowledged by the other side as "sociolinguistics has also been enriched by developments in discourse analysis, pragmatics and ethnography" . . . . The overlap is clear and some subfields of pragmatics, such as politeness and power, are also counted as subfields of sociolinguistics. A recent trend is to deal with politeness (and impoliteness) through speech acts in the history of English . . ., but it is equally possible to take a more sociolinguistic view . . . . The two disciplines have very similar topics, and titles of talks in conference programs are often very close. Further evidence of the tendency to converge is the emerging new field of historical sociopragmatics, which deals with interaction between specific aspects of social context and particular historical language use that leads to pragmatic meanings in understanding the rich dynamics of particular situations, often combining both macro- and microlevel analysis.

英語学の文脈でいえば,歴史語用論は1980年代にその兆しを見せつつ,Jucker 編の Historical Pragmatics (1995) で本格的に旗揚げされたといってよい.それから20年余の間に,著しく活発な分野へと成長してきた.結果的には,独立して発生してきた歴史社会言語学との二人三脚が成立し,融合分野としての歴史社会語用論が注目を浴びつつある.そんな状況に,いま私たちはいる.

・ Taavitsainen, Irma. "New Perspectives, Theories and Methods: Historical Pragmatics." Chapter 93 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1457--74.

・ Jucker, Andreas H., ed. Historical Pragmatics: Pragmatic Developments in the History of English. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: Benjamins, 1995.

2018-01-08 Mon

■ #3178. 産業革命期,伝統方言から都市変種へ [lmode][industrial_revolution][history][sociolinguistics][dialect][dialectology][variety][koine][dialect_levelling][bre]

18--19世紀の Industrial Revolution (産業革命)は,英国社会の構造を大きく変えた.その社会言語学的な帰結は,端的にいえば伝統方言 (traditional dialects) から都市変種 (urban varieties) への移行といってよい.交通・輸送手段の発達により,人々の行動様式や社会的ネットワークが様変わりし,各地域の内部における伝統的な人間関係が前の時代よりも弱まり,伝統方言の水平化 (dialect_levelling) と共通語化 (koinéization) が進行した.一方で,各地に現われた近代型の都市が地域社会の求心力となり,新しい方言,すなわち都市変種が生まれてきた.都市変種は地域性よりも所属する社会階級をより強く反映する傾向がある点で,伝統方言とは異なる存在である.

Gramley (181) が,この辺りの事情を以下のように説明している.

[The Industrial Revolution and the transportation revolution] were among the most significant social changes of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Partly as a prerequisite for and partly as an effect of industrialization there were fundamental changes in transportation. First, in the period after 1750 there was the establishment of turnpikes, then canals, and finally railroads. Among their consequences was the development of regional and supra-regional markets and, concomitant with this, greater labor force mobility in a money rather than barter economy with the potential for consumption. It hardly seems necessary to point out that this led to a weakening of the rural traditional dialects and an upsurge of new urban varieties in the process of dialect leveling or koinéization.

As industrialization continued, new centers in the Northeast (mining) and in the Western Midlands (textiles in Manchester and Birmingham and commerce in Liverpool) began to emerge. Immigration of labor from "abroad" also ensured further language and dialect contact as Irish workers found jobs in the major projects of canal building in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and then in the building of the railways. Enclaves of Irish came into being, especially in Liverpool. Despite linguistic leveling the general distinctions were retained between the North (now divided more clearly than ever between the English North and Scotland), the East Midlands and the now industrializing West Midlands, and the South. The emergence of a new, mostly working-class, urban population in the North in the nineteenth century was accompanied by a literature of its own. Pamphlets, broadsides, and almanacs showed local consciousness and pride in vernacular culture and language. As the novels of Elizabeth Gaskel demonstrate, language --- be it traditional dialect or working-class koiné --- was a marker of class solidarity.

このように,英国の近現代的な社会言語学的変種のあり方は,主として産業革命期の産物といってよい.

関連する話題として,「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]),「#2028. 日本とイングランドにおける方言の将来」 ([2014-11-15-1]),「#2023. England の現代英語方言区分 (3) --- Modern Dialects」 ([2014-11-10-1]) も参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2017-12-22 Fri

■ #3161. 大阪が国家として独立したら大阪語が公用語となるかも [sociolinguistics][official_language][language_planning][dialect][language_or_dialect]

未来の if シリーズ(仮称)の話題.社会言語学では "Language is a dialect with an army and a navy." が金言とされているように,言語と方言の区別はしばしばバックに国家がついているか否かで決まることが多い.古今東西,地方の1方言にすぎなかった変種が,その地方の政治的独立によって1言語へと「昇格」するということがあったし,その逆もまたあった (cf. 「#2006. 近現代ヨーロッパで自律化してきた言語」 ([2014-10-24-1])) .大阪もいつか日本国から独立して大阪国となることがあるとすれば,大阪方言あらため大阪語がその公用語となるだろう.

このネタは私も社会言語学の講義などでよく取り上げるのだが,大阪国が独立に際して採用すると見込まれる言語計画 (language_planning) や言語政策について,具体的に想像を膨らませたことはなかった.先日,図書館でブラウジングしていたら『大阪がもし日本から独立したら』という本をみつけた.その p. 58 に,大阪国民の誇りを表現する「大阪語」の公用語制定を含む言語政策のシミュレーションが解説されていた.おもしろいので引用しよう.

大阪国オリジナルの施策として,第一公用語を「大阪語」とする旨が発布されました.しかし大阪語は地域によってはまったく異なる言語となることから,かつての「船場コトバ」を基礎にした(大阪)標準語の制定作業が進められています.天下の台所と称えられた時代から,日本列島の富を左右していた商業エリアで,鎬(しのぎ)を削る商取引を正確かつ円滑に進めながら,「和」を損なうことのないコミュニケーションツールとして機能し続けてきた船場コトバの特徴を大阪国民が受け継ぐことも狙いです.

第二公用語には日本国標準語を採用.独立前後の社会活動をスムーズに継続させる実利面への配慮も怠りません.一方,国内各州の地元で親しまれてきた,河内語・摂津語・和泉語などは,各州間のコミュニケーションで誤解を招きかねないデメリットを考慮して,公用語に準ずる扱いを容認するレベルにとどめることにしました.

ちなみに「大阪語」「船場コトバ」「日本国標準語」には注が付されている.

大阪語 日本語族は従来日本語派と琉球語派の2分派に分けられていたが,大阪国内の研究者の多くは,東日本に分布する東国語派,西日本に分布する大和語派,九州に分布する西国語派と沖縄地方の琉球語派の4分派に分ける立場をとっている.「大阪語」は大和語派のなにわ語群諸語を総称していう名称.船場コトバ,泉州語,河内語などがある. (58)

船場コトバ 江戸時代の船場は堺,近江,京の商人たちが集まった日本最大の商都.そこで円滑に商いを行うために,丁寧かつ曖昧な言語として発達したのが「船場コトバ」といわれている.山崎豊子の名作『ぼんち』の題名となった,商売も遊びにも長けたデキる大阪商人を表す「ぼんち」などで知られる.(58)

日本国標準語 日本国標準語は,東京地方の方言と阪神地方の方言が混ざって生まれた東京山手地域の方言が基礎になっている.主にNHK放送により普及した.(59)

なお,大阪国を構成する7つの州をまとめる初代大統領はハシモト氏ということになっている(2010年の出版という点がポイント).

・ 大阪国独立を考える会(編) 『大阪がもし日本から独立したら』 マガジンハウス,2010年.

2017-12-15 Fri

■ #3154. 英語史上,色彩語が増加してきた理由 [bct][borrowing][lexicology][french][loan_word][sociolinguistics]

「#2103. Basic Color Terms」 ([2015-01-29-1]) および昨日の記事「#3153. 英語史における基本色彩語の発展」 ([2017-12-14-1]) で,基本色彩語 (Basic Colour Terms) の普遍的発展経路の話題に触れた.英語史においても,BCTs の種類は,普遍的発展経路から予想される通りの順序で,古英語から中英語へ,そして中英語から近代英語へと着実に増加してきた.そして,BCTs のみならず non-BCTs も時代とともにその種類を増してきた.これらの色彩語の増加は何がきっかけだったのだろうか.

Biggam (123--24) によれば,古英語から中英語にかけての増加は,ノルマン征服後のフランス借用語に帰せられるという.BCTs に関していえば,中英語で加えられたbleu は確かにフランス語由来だし,brun は古英語期から使われていたものの Anglo-French の brun により使用が強化されたという事情もあったろう.また,色合,濃淡 ,彩度,明度を混合させた古英語の BCCs 基準と異なり,中英語期にとりわけ色合を重視する BCCs 基準が現われてきたのは,ある産業技術上の進歩に起因するのではないかという指摘もある.

The dominance of hue in certain ME terms, especially in BCTs, was at least encouraged by certain cultural innovations of the later Middle Ages such as banners, livery, and the display of heraldry on coats-of-arms, all of which encouraged the development and use of strong dyes and paints. (125)

近代英語期になると,PURPLE, ORANGE, PINK が BCCs に加わり,近現代的な11種類が出そろうことになったが,この時期にはそれ以外にもおびただしい non-BCTs が出現することになった.これも,近代期の社会や文化の変化と連動しているという.

From EModE onwards, the colour vocabulary of English increased enormously, as a glance at the HTOED colour categories reveals. Travellers to the New World discovered dyes such as logwood and some types of cochineal, while Renaissance artists experimented with pigments to introduce new effects to their paintings. Much later, synthetic dyes were introduced, beginning with so-called 'mauveine', a purple shade, in 1856. In the same century, the development of industrial processes capable of producing identical items which could only be distinguished by their colours encouraged the proliferation of colour terms to identify and market such products. The twentieth century saw the rise of the mass fashion industry with its regular announcements of 'this year's colours'. In periods like the 1960s, colour, especially vivid hues, seemed to dominate the cultural scene. All of these factors motivated the coining of new colour terms. The burgeoning of the interior décor industry, which has a never-ending supply of subtle mixes of hues and tones, also brought colour to the forefront of modern minds, resulting in a torrent of new colour words and phrases. It has been estimated that Modern British English has at least 8,000 colour terms . . . . (126)

英語の色彩語の歴史を通じて,ちょっとした英語外面史が描けそうである.

・ Kay, Christian and Kathryn Allan. English Historical Semantics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

・ Biggam, C. P. "English Colour Terms: A Case Study." Chapter 7 of English Historical Semantics. Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015. 113--31.

2017-12-12 Tue

■ #3151. 言語接触により言語が単純化する機会は先史時代にはあまりなかった [contact][history][anthropology][sociolinguistics][simplification]

昨日の記事「#3150. 言語接触は言語を単純にするか複雑にするか?」 ([2017-12-11-1]) で,言語接触の結果,言語は単純化するのか複雑化するのかという問題を取り上げた.Trudgill の結論としては,単純化に至るのは "high-contact, short-term post-critical threshold contact situations" の場合に多いということだが,このような状況は,人類史上あまりなかったことであり,新石器時代以降の比較的新しい出来事ではないかという.つまり,異なる言語の成人話者どうしが短期間の濃密な接触を経験するという事態は,先史時代には決して普通のことではなかったのではないか.Trudgill (313) 曰く,

I have argued . . . that we have become so familiar with this type of simplification in linguistic change --- in Germanic, Romance, Semitic --- that we may have been tempted to regard it as normal --- as a diachronic universal. However, it is probable that

widespread adult-only language contact is a mainly a post-neolithic and indeed a mainly modern phenomenon associated with the last 2,000 years, and if the development of large, fluid communities is also a post-neolithic and indeed mainly modern phenomenon, then according to this thesis the dominant standard modern languages in the world today are likely to be seriously atypical of how languages have been for nearly all of human history. (Trudgill 2000)

逆に言えば,おそらく先史時代の言語接触に関する常態は,昨日示した類型でいえば 1 か 3 のタイプだったということになるだろう.すなわち,言語接触は互いの言語の複雑性を保持し,助長することが多かったのではないかと.何やら先史時代の平和的共存と歴史時代の戦闘的融和とおぼしき対立を感じさせる仮説である.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "Contact and Sociolinguistic Typology." The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. 2010. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2013. 299--319.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2017-11-05 Sun

■ #3114. 文化的優劣,政治的優劣,語彙借用 [sociolinguistics][contact][borrowing]

昨日の記事「#3113. アングロサクソン人は本当にイングランドを素早く征服したのか?」 ([2017-11-04-1]) で,接触言語どうしの社会言語学的な関係を記述する場合に,文化軸と政治軸を分けて考えるやり方があり得ると言及した.早速,これを英語史上の主要な言語接触に当てはめてみると,およそ次のような図式が得られる.

政治的優劣 文化・政治的同列 文化・政治的優劣 文化的優劣 ┌─────┐ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ │ │ │ │ │ ラテン語 │ │ 英 語 │ ┌───────┬───────┐ │ フランス語 │ │ or │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ ギリシア語 │ ├─────┤ │ 英 語 │ 古ノルド語 │ ├───────┤ ├───────┤ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ ケルト │ └───────┴───────┘ │ 英 語 │ │ 英 語 │ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─────┘ └───────┘ └───────┘

まず,5世紀半ばの英語とケルト語の関係でいえば,英語はケルト語に対して政治的(軍事的)には優位に立っていたが,昨日の記事でも触れたように,文化的には必ずしも優位に立っていたわけではない.この言語接触については,あくまで「政治的優劣」の関係にとどまっていたとみなすことができる.

次に,後期古英語からの英語と古ノルド語の関係についていえば,両言語の話者集団は文化的にも政治的にもおよそ同列であり,いずれかが著しく勝っていたというわけではない.確かに言語接触の背景にはヴァイキングの軍事的な成功があったが,彼我の力関係は歴然としたものではなかった.

続いて,中英語期の英語とフランス語の接触についていえば,ノルマン征服による明確な政治的・軍事的な優劣を背景として,その後,文化的な優劣の関係も生じることになった.

最後に,初期近代英語期の英語とラテン語・ギリシア語の接触に関しては,政治的な含みはないといってよく,関与するのはもっぱら文化軸においてである.

このように見てくると,英語はその歴史のなかで,文化軸と政治軸の様々な組み合わせで,接触言語と関係してきたことがわかる.ある意味で,豊富な言語接触のパターンを試してきたともいえる.

このパターンと語彙借用との相関関係について何か指摘できることがあるとすれば,文化軸が関与している言語接触(古ノルド語,フランス語,ラテン語・ギリシア語)においては英語に関して語彙借用が生じているが,政治軸のみが関与している言語接触(ケルト語)では,上位の英語のみならず下位のケルト語においても,ほとんど語彙借用が生じていないのではないか,ということだ.優劣関係それ自体よりも,文化の政治のいずれの軸での優劣関係が問題となっているのかにより,語彙借用の多寡の傾向が決まるということかもしれない.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow