2015-07-28 Tue

■ #2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率 [shakespeare][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

初期近代英語期のラテン語やギリシア語からの語彙借用は,現代から振り返ってみると,ある種の実験だった.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) で見た通り,16世紀に限っても13000語ほどが借用され,その半分以上の約7000語がラテン語からである.この時期の語彙借用については,以下の記事やインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) に関連するその他の記事でも再三取り上げてきた.

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

16世紀後半を代表する劇作家といえば Shakespeare だが,Shakespeare の語彙借用は,上記の初期近代英語期の語彙借用の全体的な事情に照らしてどのように位置づけられるだろうか.Crystal (63) は,Shakespeare において初出する語彙について,次のように述べている.

LEXICAL FIRSTS

・ There are many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have survived into Modern English. Some examples:

accommodation, assassination, barefaced, countless, courtship, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, fancy-free, lack-lustre, laughable, premeditated, submerged

・ There are also many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have not survived. About a third of all his Latinate neologisms fall into this category. Some examples:

abruption, appertainments, cadent, exsufflicate, persistive, protractive, questrist, soilure, tortive, ungenitured, unplausive, vastidity

特に上の引用の第2項が注目に値する.Shakespeare の初出ラテン借用語彙に関して,その3分の1が現代英語へ受け継がれなかったという事実が指摘されている.[2010-08-18-1]の記事で触れたように,この時期のラテン借用語彙の半分ほどしか後世に伝わらなかったということが一方で言われているので,対応する Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙が3分の2の確率で残存したということであれば,Shakespeare は時代の平均値よりも高く現代語彙に貢献していることになる.

しかし,この Shakespeare に関する残存率の相対的な高さは,いったい何を意味するのだろうか.それは,Shakespeare の語彙選択眼について何かを示唆するものなのか.あるいは,時代の平均値との差は,誤差の範囲内なのだろうか.ここには語彙の数え方という方法論上の問題も関わってくるだろうし,作家別,作品別の統計値などと比較する必要もあるだろう.このような統計値は興味深いが,それが何を意味するか慎重に評価しなければならない.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2014-12-16 Tue

■ #2059. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (2) [etymological_respelling][latin][grammatology][manuscript][silent_reading][standardisation][renaissance]

昨日の記事「#2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1)」 ([2014-12-15-1]) に引き続いての話題.

昨日引用した Perret がフランス語史において指摘したのと同趣旨で,Scragg (56) は,英語史における黙字習慣の発展と表語文字への転換とが密接に関わっていることを指摘している.

. . . an important change overtook the written language towards the end of the fourteenth century: suddenly literacy became more widespread with the advent of cheaper writing materials. In earlier centuries, while parchment was expensive and wax tablets were cumbersome, the church easily retained control of education and writing, but with the introduction of paper, mass literacy became both feasible and desirable. In the fifteenth century, private reading began to replace public recitation, and the resultant demand for books led, during that century, to the development of the printing press. As medieval man ceased pointing to the words with his bookmark as he pronounced them aloud, and turned to silent reading for personal edification and satisfaction, so his attention was concentrated more on the written word as a unit than on the speech sounds represented by its constituent letters. The connotations of the written as opposed to the spoken word grew, and given the emphasis on the classics early in the Renaissance, it was inevitable that writers should try to extend the associations of English words by giving them visual connection with related Latin ones. They may have been influences too by the fact that Classical Latin spelling was fixed, whereas that of English was still relatively unstable, and the Latinate spellings gave the vernacular an impression of durability. Though the etymologising movement lasted from the fifteenth century to the seventeenth, it was at its height in the first half of the sixteenth.

黙字習慣が確立してくると,読者は一連の文字のつながりを,その発音を介在させずに,直接に語という単位へ結びつけることを覚えた.もちろん綴字を構成する個々の文字は相変わらず表音主義を標榜するアルファベットであり,表音主義から表語主義へ180度転身したということにはならない.だが,表語主義の極へとこれまでより一歩近づいたことは確かだろう.

さらに重要と思われるのは,引用の後半で Scragg も指摘しているように,ラテン語綴字の採用が表語主義への流れに貢献し,さらに綴字の標準化の流れにも貢献したことだ.ルネサンス期のラテン語熱,綴字標準化の潮流,語源的綴字,表語文字化,黙読習慣といった諸要因は,すべて有機的に関わり合っているのである.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2014-12-15 Mon

■ #2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1) [french][etymological_respelling][latin][grammatology][manuscript][scribe][silent_reading][renaissance][hfl]

一昨日の記事「#2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1)」 ([2014-12-13-1]) で,フランス語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) が同音異義語どうしを区別するのに役だったという点に触れた.フランス語において語源的綴字がそのような機能を得たということは,別の観点から言えば,フランス語の書記体系が表音 (phonographic) から表語 (logographic) へと一歩近づいたとも表現できる.このような表語文字体系への接近が,英語では中英語から近代英語にかけて生じていたのと同様に,フランス語では古仏語から中仏語にかけて生じていた.むしろフランス語での状況の方が,英語より一歩も二歩も先に進んでいただろう.(cf. 「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1]).)

フランス語の状況に関しては,当然ながら英語史ではなくフランス語史の領域なので,フランス語史概説書に当たってみた.以下,Perret (138) を引用しよう.まずは,古仏語の書記体系は表音的であるというくだりから.

L'ancien français : une écriture phonétique

. . . . dans la mesure où l'on disposait de graphèmes pour rendre les son que l'on entendait, l'écriture était simplement phonétique (feré pour fairé, souvent kí pour quí) . . . .

Perret (138--39) は続けて,中仏語の書記体系の表語性について次のように概説している.

Le moyen français : une écriture idéographique

À partir du XIIIe siècle, la transmission des textes cesse d'être uniquement orale, la prose commence à prendre de l'importance : on écrit aussi des textes juridiques et administratifs en français. Avec la prose apparaît une ponctuation très différente de celle que nous connaissons : les textes sont scandés par des lettrines de couleur, alternativement rouges et bleues, qui marquent le plus souvent des débuts de paragraphes, mais pas toujours, et des points qui correspondent à des pauses, généralement en fin de syntagme, mais pas forcément en fin de phrase. Les manuscrits deviennent moins rares et font l'objet d'un commerce, ils ne sont plus recopiés par des moines, mais des scribes séculiers qui utilisent une écriture rapide avec de nombreuses abréviations. On change d'écriture : à l'écriture caroline succèdent les écritures gothique et bâtarde dans lesquelles certains graphèmes (les u, n et m en particulier) sont réduits à des jambages. C'est à partir de ce moment qu'apparaissent les premières transformations de l'orthographe, les ajouts de lettres plus ou moins étymologiques qui ont parfois une fonction discriminante. C'est entre le XIVe et le XVIe siècle que s'imposent les orthographes hiver, pied, febve (où le b empêche la lecture ‘feue’), mais (qui se dintingue ainsi de mes); c'est alors aussi que se développent le y, le x et le z à la finale des mots. Mais si certains choix étymologiques ont une fonction discrminante réelle, beaucoup semblent n'avoir été ajoutés, pour le plaisir des savants, qu'afin de rapprocher le mot français de son étymon latin réel ou supposé (savoir s'est alors écrit sçavoir, parce qu'on le croyait issu de scire, alors que ce mot vient de sapere). C'est à ce moment que l'orthographe française devient de type idéographique, c'est-à-dire que chaque mot commence à avoir une physionomie particulière qui permet de l'identifier par appréhension globale. La lecture à haute voix n'est plus nécessaire pour déchiffrer un texte, les mots peuvent être reconnus en silence par la méthode globale.

引用の最後にあるように,表語文字体系の発達を黙読習慣の発達と関連づけているところが実に鋭い洞察である.声に出して読み上げる際には,発音に素直に結びつく表音文字体系のほうがふさわしいだろう.しかし,音読の機会が減り,黙読が通常の読み方になってくると,内容理解に直結しやすいと考えられる表語(表意)文字体系がふさわしいともいえる (cf. 「#1655. 耳で読むのか目で読むのか」 ([2013-11-07-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1])) .音読から黙読への転換が,表音文字から表語文字への転換と時期的におよそ一致するということになれば,両者の関係を疑わざるを得ない.

フランス語にせよ英語にせよ,語源的綴字はルネサンス期のラテン語熱との関連で論じられるのが常だが,文字論の観点からみれば,表音から表語への書記体系のタイポロジー上の転換という問題ともなるし,書物文化史の観点からみれば,音読から黙読への転換という問題ともなる.<doubt> の <b> の背後には,実に学際的な世界が広がっているのである.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2014-12-14 Sun

■ #2057. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (2) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][scribe][anglo-norman][renaissance]

昨日の記事に引き続き,英仏両言語における語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の関係について.Scragg (52--53) は,次のように述べている.

Throughout the Middle Ages, French scribes were very much aware of the derivation of their language from Latin, and there were successive movements in France for the remodelling of spelling on etymological lines. A simple example is pauvre, which was written for earlier povre in imitation of Latin pauper. Such spellings were particularly favoured in legal language, because lawyers' clerks were paid for writing by the inch and superfluous letters provided a useful source of income. Since in France, as in England, conventional spelling grew out of the orthography of the chancery, at the heart of the legal system, many etymological spellings became permanently established. Latin was known and used in England throughout the Middle Ages, and there was a considerable amount of word-borrowing from it into English, particularly in certain registers such as that of theology, but since the greater part of English vocabulary was Germanic, and not Latin-derived, it is not surprising that English scribes were less affected by the etymologising movements than their French counterparts. Anglo-Norman, the dialect from which English derived much of its French vocabulary, was divorced from the mainstream of continental French orthographic developments, and any alteration in the spelling of Romance elements in the vocabulary which occurred in English in the fourteenth century was more likely to spring from attempts to associate Anglo-Norman borrowings with Parisian French words than from a concern with their Latin etymology. Etymologising by reference to Latin affected English only marginally until the Renaissance thrust the classical language much more positively into the centre of the linguistic arena.

重要なポイントをまとめると,

(1) 中世フランス語におけるラテン語源を参照しての文字の挿入は,写字生の小金稼ぎのためだった.

(2) フランス語に比べれば英語にはロマンス系の語彙が少なく(相対的にいえば確かにその通り!),ラテン語源形へ近づけるべき矯正対象となる語もそれだけ少なかったため,語源的綴字の過程を経にくかった,あるいは経るのが遅れた (cf. 「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1])) .

(3) 14世紀の英語の語源的綴字は,直接ラテン語を参照した結果ではなく,Anglo-Norman から離れて Parisian French を志向した結果である.

(4) ラテン語の直接の影響は,本格的にはルネサンスを待たなければならなかった.

では,なぜルネサンス期,より具体的には16世紀に,ラテン語源形を直接参照した語源的綴字が英語で増えたかという問いに対して,Scragg (53--54) はラテン語彙の借用がその時期に著しかったからである,と端的に答えている.

As a result both of the increase of Latinate vocabulary in English (and of Greek vocabulary transcribed in Latin orthography) and of the familiarity of all literate men with Latin, English spelling became as affected by the etymologising process as French had earlier been.

確かにラテン語彙の大量の流入は,ラテン語源を意識させる契機となったろうし,語源的綴字への影響もあっただろうとは想像される.しかし,語源的綴字の潮流は前時代より歴然と存在していたのであり,単に16世紀のラテン語借用の規模の増大(とラテン語への親しみ)のみに言及して,説明を片付けてしまうのは安易ではないか.英語における語源的綴字の問題は,より大きな歴史的文脈に置いて理解することが肝心なように思われる.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2014-12-13 Sat

■ #2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][hypercorrection][renaissance][hfl]

中英語期から近代英語期にかけての英語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の発生と拡大の背後には,対応するフランス語での語源的綴字の実践があった.このことについては,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]),「#1156. admiral の <d>」 ([2012-06-26-1]),「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]),「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]) などの記事で触れてきたとおりである.

したがって,英語におけるこの問題を突き詰めようとすれば,フランス語史を参照せざるをえない.14--16世紀の中世フランス語の語源的綴字の実践について,Zink (24--25) を引用しよう.

Latinisation et surcharge graphique. --- L'idée de rapprocher les mots français de leurs étymons latins ne date pas de la Renaissance. Le mouvement de latinisation a pris naissance à la fin du XIIIe siécle avec les emprunts opérés par la langue juridique au droit romain sous forme de calques à peine francisés.... Parti du vocabulaire savant, il a gagné progressivement les mots courants de l'ancien fonds. Il ne pouvait s'agir dans ce dernier cas que de réfections purement graphiques, sans incidence sur la prononciation ; aussi est-ce moins le vocalisme qui a été retouché que le consonantisme par l'insertion de graphèmes dans les positions où on ne les prononçait plus : finale et surtout intérieure implosive.

Ainsi s'introduisent avec le flot des emprunts savants : adjuger, exception (XIIIe s.) ; abstraire, adjonction, adopter, exemption, subjectif, subséquent. . . (mfr., la prononciation actuelle datant le plus souvent du XVIe s.) et l'on rhabille à l'antique une foule de mots tels que conoistre, destre, doter, escrit, fait, nuit, oscur, saint, semaine, soissante, soz, tens en : cognoistre, dextre, doubter, escript, faict, nuict, obscur, sainct, sepmaine, soixante, soubz, temps d'après cognoscere, dextra, dubitare, scriptum, factum, noctem, obscurum, sanctum, septimana, sexaginta, subtus, tempus.

Le souci de différencier les homonymes, nombreux en ancien français, entre aussi dans les motivations et la langue a ratifié des graphies comme compter (qui prend le sens arithmétique au XVe s.), mets, sceau, sept, vingt, bien démarqués de conter, mais/mes, seau/sot, sait, vint.

Toutefois, ces correspondances supposent une connaissance étendue et précise de la filiation des mot qui manque encore aux clercs du Moyen Age, d'où des tâtonnements et des erreurs. Les rapprochements fautifs de abandon, abondant, oster, savoir (a + bandon, abundans, obstare, sapere) avec habere, hospitem (!), scire répandent les graphies habandon, habondant, hoster, sçavoir (à toutes les formes). . . .

要点としては,(1) フランス語ではルネサンスに先立つ13世紀末からラテン語借用が盛んであり,それに伴ってラテン語に基づく語源的綴字も現われだしていたこと,(2) 語末と語中の子音が脱落していたところに語源的な子音字を復活させたこと,(3) 語源的綴字を示すいくつかの単語が英仏両言語において共通すること,(4) フランス語の場合には語源的綴字は同音異義語どうしを区別する役割があったこと,(5) フランス語でも語源的綴字に基づき,それを延長させた過剰修正がみられたこと,が挙げられる.これらの要点はおよそ英語の語源的綴字を巡る状況にもあてはまり,英仏両言語の類似現象が関与していること,もっと言えばフランス語が英語へ影響を及ぼしたことが示唆される.(5) に挙げた過剰修正 (hypercorrection) の英語版については,「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3)」 ([2014-07-09-1]),「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) も参照されたい.

語源的綴字を巡る状況に関して英仏語で異なると思われるのは,上記 (4) だろう.フランス語では,語源的綴字の導入は,同音異義語 (homonymy) を区別するのに役だったという.換言すれば,書記において同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) を避けるために,語源的原則に基づいて互いに異なる綴字を導入したということである.ラテン語からロマンス諸語へ至る過程で生じた数々の音韻変化の結果,フランス語では単音節の同音異義語が大量に生じるに至った.この問題を書記において解決する策として,語源的綴字が利用されたのである.日本語のひらがなで「こうし」と書いてもどの「こうし」か区別が付かないので,漢字で「講師」「公私」「嚆矢」などと書き分ける状況と似ている.ここにおいてフランス語の書記体系は,従来の表音的なものから,表語的なものへと一歩近づいたといえるだろう.

英語では同音異義衝突を避けるために語源的綴字を導入するという状況はなかったように思われるが,機能主義的な語源的綴字の動機付けという点については,もう少し注意深く考察する価値がありそうだ.

・ Zink, Gaston. ''Le moyen françis (XIVe et XV e siècles)''. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1990.[sic]

2013-10-21 Mon

■ #1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点 [french][latin][renaissance][lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][reestablishment_of_english][language_shift]

フランス語借用の爆発期は「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たように14世紀である.このタイミングについては,「#1205. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか」 ([2012-08-14-1]) や「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1]) の記事で話題にしたように,イングランドにおいて英語が復権してきた時期と重なる.それまでフランス語が担ってきた社会的な機能を英語が肩代わりすることになり,突如として大量の語彙が必要となったからとされる.フランス語を話していたイングランドの王侯貴族にとっては,英語への言語交替 (language shift) が起こっていた時期ともいえる(「#1540. 中英語期における言語交替」 ([2013-07-15-1]) を参照).

一方,ラテン語借用の爆発期は,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) や「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) で見たように,16世紀後半を中心とする時期である.このタイミングは,それまでラテン語が担ってきた社会的な機能,とりわけ高尚な書き物の言語にふさわしいとされてきた地位を,英語が徐々に肩代わりし始めた時期と重なる.ルネサンスによる新知識の爆発のために突如として大量の語彙が必要になり,英語は追いつけ,追い越せの目標であるラテン語からそのまま語彙を借用したのだった.このようにラテン語熱がいやましに高まったが,裏を返せば,そのときまでに人々の一般的なラテン語使用が相当落ち込んでいたことを示唆する.イングランド知識人の間に,ある意味でラテン語から英語への言語交替が起こっていたとも考えられる.

つまり,フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用の最盛期は異なってはいるものの,共通項として「英語への言語交替」がくくりだせるように思える.ここでの「言語交替」は文字通りの母語の乗り換えではなく,それまで相手言語がもっていた社会言語学的な機能を,英語が肩代わりするようになったというほどの意味で用いている.この点を指摘した Fennell (148) の洞察の鋭さを評価したい.

As is often the case when use of a language ceases (as French did at the end of the Middle English period), the demise of Latin coincides with the borrowing of huge numbers of Latin words into English in order to fill perceived gaps in the language.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

2013-07-05 Fri

■ #1530. イングランド紙幣に表記されている Compa [abbreviation][italian][renaissance][etymology]

これはイングランドの50ポンド札の写しである.上方から左中程にかけて,"I PROMISE TO PAY THE BEARER ON DEMAND THE SUM OF FIFTY POUNDS For the Gov:r and Comp:a of the BANK of ENGLAND" という文が読める."Gov:r" は governor,"Comp:a" は company の略だが,このような略記は一般にはお目にかからない.特に company は co と省略されるのが普通であり,compa は珍しいだろう.実際に,OED (compa | Compa, n.) を参照すると,現在では紙幣における表記としての使用がほぼ唯一の使用例であるという.

1940 G. Crowther Outl. Money i. 25 Every Bank of England note..bears the legend, 'I Promise to pay the Bearer on Demand the sum of One Pound' ..signed, 'For the Govr'. and Compa. of the Bank of England' by the Chief Cashier.

これを Company (< ME compaignie < AF compainie = OF compa(i)gnie) の略記であると解釈することに異論はないが,歴史的にはイングランドに銀行業をもたらしたイタリアとの関連で,イタリア語の同根語 compagnia の影響を認めてもよいかもしれない.Praz (35) は,次のように述べている.

Banking, as is well known, was first introduced into England by Italians; first by Sienese, then, after the middle of the thirteenth century, by Florentine merchants; Venice appeared on the scene at the beginning of the fourteenth century. Italian merchants were protected by Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell; they began to lose ground only during the age of Elizabeth. . . . The abbreviation Comp:a on the Bank of England notes is nothing else but a faint echo of the vanished glory of many an Italian Compagnia or firm.

「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) の最後に触れた通り,ロマンス諸語からの借用の多くは,フランス語を経由するなどしてフランス語化した形態で英語に入ってくることが多かった.語の借用過程は主として形態を参照しながら探るのが歴史言語学の定石だが,語源学や語誌研究においては形態以外の項目にも注意を払うと,新たな洞察が得られて実り豊かである.

・ Praz, Mario. "The Italian Element in English." Essays and Studies 15 (1929): 20--66.

2013-05-08 Wed

■ #1472. ルネサンス期の聖書翻訳の言語的争点 [bible][renaissance][emode][methodology][reformation]

「#1427. 主要な英訳聖書に関する年表」 ([2013-03-24-1]) から明らかなように,16世紀は様々な聖書が爆発的に出版された時代だった(もう1つの爆発期は20世紀).当時は宗教改革の時代であり,様々なキリスト教派の存在,古典語からの翻訳の長い伝統,出版の公式・非公式の差など諸要素が絡み合い,異なる版の出現を促した.当然ながら,各版は独自の目的や問題意識をもっており,言語的な点においても独自のこだわりをもっていた.では,この時代の聖書翻訳家たちが関心を寄せていた言語的争点とは,具体的にどのようなものだったのだろうか.Görlach (5) によれば,以下の4点である.

1. Should a translator use the Latin or Greek/Hebrew sources?

2. Should translational equivalents be fixed, or varying renderings be permitted according to context? (cf. penitentia = penance, penitence, amendment)

3. To what extent should foreign words be permitted or English equivalents be used, whether existing lexemes or new coinages (cf. Cheke's practice)?

4. How popular should the translator's language be? There was a notable contrast between the Protestant tradition (demanding that the Bible should be accessible to all) and the Catholic (claiming that even translated Bibles needed authentic interpretation by the priest). Note also that dependence on earlier versions increased the conservative, or even archaic character of biblical diction from the sixteenth century on

それぞれの問いへの答えは,翻訳家によって異なっており,これが異なる聖書翻訳の出版を助長した.まったく同じ形ではないにせよ,20--21世紀にかけての2度目の聖書出版の爆発期においても,これらの争点は当てはまるのではないか.

さて,英語史の研究では,異なる時代の英訳聖書を比較するという手法がしばしば用いられてきたが,各版のテキストの異同の背景に上のような問題点が関与していたことは気に留めておくべきである.複数の版のあいだの単純比較が有効ではない可能性があるからだ.Görlach (6) によれば,より一般的な観点から,聖書間の単純比較が成立しない原因として次の4点を挙げている.

1. the translators used different sources;

2. older translations were used for comparison;

3. the source was misunderstood or interpreted differently;

4. concepts and contexts were absent from the translator's language and culture.

様々な英訳聖書の存在が英語史研究に貴重な資料を提供してくれたことは間違いない.だが,英語史研究の方法論という点からみると,相当に複雑な問題を提示してくれていることも確かである.

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

2013-04-29 Mon

■ #1463. euphuism [style][literature][inkhorn_term][johnson][emode][renaissance][alliteration][rhetoric]

「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) で,15世紀に発生したラテン借用語を駆使する華麗語法について見た.続く16世紀には,inkhorn_term と呼ばれるほどのラテン語かぶれした語彙が押し寄せた.これに伴い,エリザベス朝の文体はラテン作家を範とした技巧的なものとなった.この技巧は John Lyly (1554--1606) によって最高潮に達した.Lyly は,Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit (1578) および Euphues and His England (1580) において,後に標題にちなんで呼ばれることになった euphuism (誇飾体)という華麗な文体を用い,初期の Shakespeare など当時の文芸に大きな影響を与えた.

euphuism の特徴としては,頭韻 (alliteration),対照法 (antithesis),奇抜な比喩 (conceit),掛けことば (paronomasia),故事来歴への言及などが挙げられる.これらの修辞法をふんだんに用いた文章は,不自然でこそあれ,人々に芸術としての散文の魅力をおおいに知らしめた.例えば,Lyly の次の文を見てみよう.

If thou perceive thyself to be enticed with their wanton glances or allured with their wicket guiles, either enchanted with their beauty or enamoured with their bravery, enter with thyself into this meditation.

ここでは,enticed -- enchanted -- enamoured -- enter という語頭韻が用いられているが,その間に wanton glances と wicket guiles の2重頭韻が含まれており,さらに enchanted . . . beauty と enamoured . . . bravery の組み合わせ頭韻もある.

euphuism は17世紀まで見られたが,17世紀には Sir Thomas Browne (1605--82), John Donne (1572--1631), Jeremy Taylor (1613--67), John Milton (1608--74) などの堂々たる散文が現われ,世紀半ばからの革命期以降には John Dryden (1631--1700) に代表される気取りのない平明な文体が優勢となった.平明路線は18世紀へも受け継がれ,Joseph Addison (1672--1719), Sir Richard Steele (1672--1729), Chesterfield (1694--1773),また Daniel Defoe (1660--1731), Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が続いた.だが,この平明路線は,世紀半ば,Samuel Johnson (1709--84) の荘重で威厳のある独特な文体により中断した.

初期近代英語期の散文文体は,このように華美と平明とが繰り返されたが,その原動力がルネサンスの熱狂とそれへの反発であることは間違いない.ほぼ同時期に,大陸諸国でも euphuism に相当する誇飾体が流行したことを付け加えておこう.フランスでは préciosité,スペインでは Gongorism,イタリアでは Marinism などと呼ばれた(ホームズ,p. 118).

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ 石橋 幸太郎 編 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

・ U. T. ホームズ,A. H. シュッツ 著,松原 秀一 訳 『フランス語の歴史』 大修館,1974年.

2013-03-09 Sat

■ #1412. 16世紀前半に語彙的貢献をした2人の Thomas [emode][renaissance][lexicology][loan_word][shakespeare][bible]

英語史では,特定の作家や作品がその後の英語の発展において大きな役割を果たしたと明言できる例は多くないということが言われる.そのなかで,初期近代英語を代表する Shakespeare や The King James Bible は例外だと言われることもある.そこに現われる多くの語彙や表現が,現代英語に伝わっており,広く用いられているからだ.確かに,質においても量においても,この両者の影響は他の作家や作品を圧倒している.

ここから連想されるのは,後期中英語の Chaucer の英語史上,特に英語語彙史上の意義を巡る議論である.「#257. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは?」 ([2010-01-09-1]), 「#298. Chaucer が英語史上に果たした役割とは? (2) 」 ([2010-02-19-1]), 「#524. Chaucer の用いた英語本来語 --- stevene」 ([2010-10-03-1]) で見たとおり,最近の議論では,中英語におけるフランス語借用の重要な部分を Chaucer に帰する従来の見解に対する慎重論が出されている.借用語を英語文献に初出させるのはほぼ常に個人だが,そうだからといってその個人が英語語彙史上の栄光を独り占めにしてよいということにはならない.借用熱に浮かされた時代に生まれ,書く機会とある程度の文才があれば,ある借用語を初出させること自体は可能である.多くの場合,語彙の初出に関わる個人の貢献は,その個人そのものに帰せられるべきというよりは,そのような個人を輩出させた時代の潮流に帰せられるべきだろう.特に,そのような個人が複数現われる時代には,なおさらである.

Utopia (1516) を著わした Sir Thomas More (1478--1535) や The Boke named the Governour (1531) を著わした Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546) がその例として挙げるにふさわしいかもしれない.Baugh and Cable (229) によれば,More は次のような借用語(あるいはその特定の語義)を初出させた.

absurdity, acceptance, anticipate, combustible, compatible, comprehensible, concomitance, congratulatory, contradictory, damnability, denunciation, detector, dissipate, endurable, eruditely, exact, exaggerate, exasperate, explain, extenuate, fact, frivolous, impenitent, implacable, incorporeal, indifference, insinuate, inveigh, inviolable, irrefragable, monopoly, monosyllable, necessitate, obstruction, paradox, pretext

一方,Elyot は以下の語彙を導入した.

accommodate, adumbrate, adumbration, analogy, animate, applicate, beneficence, encyclopedia, exerp (excerpt), excogitate, excogitation, excrement, exhaust, exordium, experience (v.), exterminate, frugality, implacability, infrequent, inimitable, irritate, modesty, placability

赤字で示したものは,「#708. Frequency Sorter CGI」([2011-04-05-1]) にかけて,頻度にして800回以上現われる上位6318位までに入る語である.当時難語と言われた可能性があるというのが信じられないほどに,現在では普通の語だ.

Baugh and Cable (230) は,この2人の人文主義者の語彙的貢献を,上に述べた私の見解とは異なり,ともすると全面的に個人に帰しているように読める.

So far as we now know, these words had not been used in English previously. In addition both writers employ many words that are recorded from only a few years before. And so they either introduced or helped to establish many new words in the language. What More and Elyot were doing was being done by numerous others, and it is necessary to recognize the importance of individuals as "makers of English" in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century.

しかし,最後の "the importance of individuals as "makers of English" in the sixteenth and early seventeenth century" が意味しているのはある特定の時代に属する複数の個人の力のことであり,私の述べた「そのような個人を輩出させた時代の潮流に帰せられる」という見解とも矛盾しないようにも読める.

この問題は,時代が個人を作るのか,個人が時代を作るのかという問題なのだろうか.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-08 Fri

■ #1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language" [emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][lexicology][loan_word][french][italian][spanish][portuguese]

「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) の記事で,この時代の英語が抱えていた3つ目の問題として "the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" を挙げた.この3日間の記事 ([2013-03-05-1], [2013-03-06-1], [2013-03-07-1]) で,古典語からの大量の語彙借用という潮流によって反動的に引き起こされたインク壺語論争や純粋主義者による古語への回帰の運動について見てきた.異なる陣営から "inkhorn terms" や "Chaucerisms" への批判がなされたわけだが,もう1つ,あまり目立たないのだが,槍玉に挙げられた語彙がある."oversea language" と呼ばれる,ラテン語やギリシア語以外の言語からの借用語である.大量の古典語借用へと浴びせられた批判のかたわらで,いわばとばっちりを受ける形で,他言語からの借用語も非難の対象となった.

「#151. 現代英語の5特徴」 ([2009-09-25-1]) や「#110. 現代英語の借用語の起源と割合」で触れたように,現代英語は約350の言語から語彙を借用している.初期近代英語の段階でも英語はすでに50を超える言語から語彙を借用しており (Baugh and Cable, pp. 227--28) ,「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]) で見たように,ラテン語とギリシア語を除けば,フランス語,イタリア語,スペイン語が優勢だった.

以下,Baugh and Cable (228--29) よりロマンス諸語からの借用語を示そう.まずは,フランス語から入った借用語のサンプルから.

alloy, ambuscade, baluster, bigot, bizarre, bombast, chocolate, comrade, detail, duel, entrance, equip, equipage, essay, explore, genteel, mustache, naturalize, probability, progress, retrenchment, shock, surpass, talisman, ticket, tomato, vogue, volunteer

次に,イタリア語からは建築関係の語彙が多い.赤字のものはフランス語化して入ってきたイタリア語起源の語である.

algebra, argosy, balcony, battalion, bankrupt, bastion, brigade, brusque, cameo, capricio (caprice), carat, cavalcade, charlatan, cupola, design, frigate, gala, gazette, granite, grotesque, grotto, infantry, parakeet, piazza, portico, rebuff, stanza, stucco, trill, violin, volcano

スペイン語(およびポルトガル語)からは,海事やアメリカ植民地での活動を映し出す語彙が多い.赤字はフランス語化して入ったもの.

alligator, anchovy, apricot, armada, armadillo, banana, barricade, bastiment, bastinado, bilbo, bravado, brocade, cannibal, canoe, cavalier, cedilla, cocoa, corral, desperado, embargo, escalade, grenade, hammock, hurricane, maize, mosquito, mulatto, negro, palisade, peccadillo, potato, renegado, rusk, sarsaparilla, sombrero, tobacco, yam

上に赤字で示したように,フランス語経由あるいはフランス語化した形態で入ってきた語が少なからず確認される.これは,イタリア語やスペイン語から,同じような語彙が英語へもフランス語へも流入したからである.その結果として,異なるロマンス諸語の語形が融合したかのようにみえる例が散見される.例えば,英語 galleon は F. galion, Sp. galeon, Ital. galeone のどの語形とも一致しないし,gallery もソースは Fr. galerie, Sp., Port., Ital. galeria のいずれとも決めかねる.同様に,pistol は F. pistole, Sp., Ital. pistola のいずれなのか,cochineal は F. cochenille, Sp. cochinilla, Ital. cocciniglia のいずれなのか,等々.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-07 Thu

■ #1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰 [inkhorn_term][lexicology][emode][renaissance][chaucer][loan_translation][purism]

昨日の記事「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で,初期近代英語期あるいはルネサンス期のインク壺語批判を眺めてきた.ラテン語やギリシア語からの無差別な借用を批判する論者としては,「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) で触れたように,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Sir Thomas Chaloner, Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) などの名前が挙がるが,このなかでも Cheke のような論者はその反動で純粋主義に走り,本来語への回帰を主張した.新しい語彙が必要なのであれば,誰にでもわかる本来語要素を用いた造語を用いるのが得策であり,小難しい借用語など百害あって一利なしだという考えだ.同じ考えをもち,ともに古典語学者である Ascham とともに,Cheke はこの時期における簡潔にして明快な英語の書き手として評価されている.

例えば,Cheke はマタイ伝の翻訳にあたって,欽定訳聖書 (The King James Bible) では借用語が使われているところで,本来語に由来する語を用いた.lunatic に対して mooned,publican に対して toller,その他 hundreder (centurion), foresayer (prophet), byword (parable), freshman (proselyte), crossed (crucified), gainrising (resurrection) .まさに purist らしい,古色蒼然たるゲルマン語への回帰だ.

Cheke のような人物とはやや異なる動機づけで,詩人たちもまた古語への回帰を示す傾向が強かった.ラテン語彙があふれる時代にあって,Chaucer 時代への憧憬が止みがたかったのだろうか,Edmund Spenser (1552/53--99) は "Chaucerism" とも呼ばれる古語への依存を強めた詩人として知られる.Horace の翻訳者 Thomas Drant や,John Milton (1608--74) も古語回帰の気味があった.彼らの詩においては,astound, blameful, displeasance, enroot, forby (hard by, past), empight (fixed, implanted), natheless, nathemore, mickle, whilere (a while before) などの本来語が復活した.ほかにも,ゲルマン語要素を(少なくとも部分的に)もとにした(と想定される)語形成や古語としては以下のものがある.

askew, baneful, bellibone (a fair maid), belt, birthright, blandishment, blatant, braggadocio, briny, changeful, changeling, chirrup, cosset (lamb), craggy, dapper, delve (pit, den), dit (song), don, drear, drizzling, elfin, endear, enshrine, filch, fleecy, flout, forthright, freak, gaudy, glance, glee, glen, gloomy, grovel, hapless, merriment, oaten, rancorous, scruze (squeeze, crush), shady, squall (to cry), sunshiny, surly, wakeful, wary, witless, wolfish, wrizzled (wrinkled, shriveled)

これらの純粋主義者による反動的な運動は,それ自体も批判を浴びることがあったが,上記語彙のなかには,現在,一般的に用いられているものも含まれている.インク壺批判には,英語語彙史上,このように生産的な側面もあったことを見逃してはならない.以上,Baugh and Cable (230--31) を参照して記述した.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-06 Wed

■ #1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語 [inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

昨日の記事「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で,初期近代英語期に大量に流入した古典語由来の小難しい借用語の話題を扱ってきた.「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) で挙げたように,当時は「インク壺語」と揶揄されながらも,現代にまで生き残った有用な語も多い.一方で,現代にまで伝わらなかった語も少なくない.今回は,Baugh and Cable (223--24, 226) から,生き残った語彙とほぼ死に絶えた語彙の例をさらに追加したい.

まずは生き残った語彙のサンプルを,名詞,形容詞,動詞の順に挙げる.大半はラテン語由来だが,赤字で示したようにギリシア語由来のもの(ラテン語を経由したものを含む)も多い.

acme, allurement, allusion, anachronism, antipathy, antithesis, atmosphere, autograph, capsule, catastrophe, chaos, chronology, climax, crisis, criterion, democracy, denunciation, dexterity, disability, disrespect, dogma, emanation, emphasis, encyclopedia, enthusiasm, epitome, excrescence, excursion, expectation, halo, idiosyncrasy, inclemency, jurisprudence, lexicon, misanthrope, parasite, parenthesis, pathetic, pneumonia, scheme, skeleton, system, tactics, thermometer

abject, agile, anonymous, appropriate, caustic, conspicuous, critic, dexterous, ephemeral, expensive, external, habitual, hereditary, heterodox, impersonal, insane, jocular, malignant, polemic, tonic

adapt, alienate, assassinate, benefit, consolidate, disregard, emancipate, eradicate, erupt, excavate, exert, exhilarate, exist, extinguish, harass, meditate, ostrasize, tantalize

次に,死語あるいは事実上の廃用となったもののサンプルを,名詞,形容詞,動詞の順に,語義とともに挙げる.

adminiculation (aid), appendance (appendage), assation (roasting), discongruity (incongruity), mansuetude (mildness)

aspectable (visible), eximious (excellent, distinguished), exolete (faded), illecebrous (delicate, alluring), temulent (drunk)

approbate (to approve), assate (to roast), attemptate (to attempt), cautionate (to caution), cohibit (to restrain), consolate (to console), consternate (to dismay), demit (to send away), denunciate (to denounce), deruncinate (to weed), disaccustom (to render unaccustomed), disacquaint (to make acquainted), disadorn (to deprive of adornment), disquantity (to diminish), emacerate (to emaciate), exorbitate (to stray from the ordinary course), expede (to accomplish, expedite), exsiccate (to desiccate), suppeditate (to furnish, supply)

湯水の如き借用は実験的な借用ともいうことができる.実験的な性格は,現在も用いられている effective, effectual に加えて,effectful, effectuating, effectuous などがかつて使われていた事実からも知れるだろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-05 Tue

■ #1408. インク壺語論争 [popular_passage][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek][purism]

16世紀のインク壺語 (inkhorn term) を巡る問題の一端については,昨日の記事「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) 以前にも,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) ,「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で触れてきた.インク壺語批判の先鋒としては,[2010-11-24-1]で引用した The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) の著者 Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) が挙げられるが,もう1人挙げるとするならば Sir John Cheke (1514--57) がふさわしい.Cheke は自らがギリシア語学者でありながら,古典語からのむやみやたらな借用を強く非難した.同じくギリシア語学者である Roger Ascham (1515?--68) も似たような態度を示していた点が興味深い.Cheke は Sir Thomas Hoby に宛てた手紙 (1561) のなかで,純粋主義の主張を行なった(Baugh and Cable, pp. 217--18 より引用).

I am of this opinion that our own tung shold be written cleane and pure, unmixt and unmangeled with borowing of other tunges, wherin if we take not heed by tijm, ever borowing and never payeng, she shall be fain to keep her house as bankrupt. For then doth our tung naturallie and praisablie utter her meaning, when she bouroweth no counterfeitness of other tunges to attire her self withall, but useth plainlie her own, with such shift, as nature, craft, experiens and folowing of other excellent doth lead her unto, and if she want at ani tijm (as being unperfight she must) yet let her borow with suche bashfulnes, that it mai appeer, that if either the mould of our own tung could serve us to fascion a woord of our own, or if the old denisoned wordes could content and ease this neede, we wold not boldly venture of unknowen wordes.

Erasmus の Praise of Folly を1549年に英訳した Sir Thomas Chaloner も,インク壺語の衒学たることを揶揄した(Baugh and Cable, p. 218 より引用).

Such men therfore, that in deede are archdoltes, and woulde be taken yet for sages and philosophers, maie I not aptelie calle theim foolelosophers? For as in this behalfe I have thought good to borowe a littell of the Rethoriciens of these daies, who plainely thynke theim selfes demygods, if lyke horsleches thei can shew two tongues, I meane to mingle their writings with words sought out of strange langages, as if it were alonely thyng for theim to poudre theyr bokes with ynkehorne termes, although perchaunce as unaptly applied as a gold rynge in a sowes nose. That and if they want suche farre fetched vocables, than serche they out of some rotten Pamphlet foure or fyve disused woords of antiquitee, therewith to darken the sence unto the reader, to the ende that who so understandeth theim maie repute hym selfe for more cunnyng and litterate: and who so dooeth not, shall so muche the rather yet esteeme it to be some high mattier, because it passeth his learnyng.

"foolelosophers" とは厳しい.

このようにインク壺語批判はあったが,時代の趨勢が変わることはなかった.インク壺語を(擁護したとは言わずとも)穏健に容認した Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546) や Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) などの主たる人文主義者たちの示した態度こそが,時代の潮流にマッチしていたのである.

なお,OED によると,ink-horn term という表現の初出は1543年.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-04 Mon

■ #1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題 [emode][renaissance][popular_passage][orthoepy][orthography][spelling_reform][standardisation][mulcaster][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicology][hart]

初期近代英語期,特に16世紀には英語を巡る大きな問題が3つあった.Baugh and Cable (203) の表現を借りれば,"(1) recognition in the fields where Latin had for centuries been supreme, (2) the establishment of a more uniform orthography, and (3) the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" である.

(1) 16世紀は,vernacular である英語が,従来ラテン語の占めていた領分へと,その機能と価値を広げていった過程である.世紀半ばまでは,Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Thomas Wilson (1525?--81) , George Puttenham (1530?--90) に代表される英語の書き手たちは,英語で書くことについてやや "apologetic" だったが,世紀後半になるとそのような詫びも目立たなくなってくる.英語への信頼は,特に Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) の "I love Rome, but London better, I favor Italie, but England more, I honor the Latin, but I worship the English." に要約されている.

(2) 綴字標準化の動きは,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Sir Thomas Smith (1513--77; De Recta et Emendata Linguae Anglicae Scriptione Dialogus [1568]), John Hart (d. 1574; An Orthographie [1569]), William Bullokar (fl. 1586; Book at Large [1582], Bref Grammar for English [1586]) などによる急進的な表音主義的な諸提案を経由して,Richard Mulcaster (The First Part of the Elementarie [1582]), E. Coot (English Schoole-master [1596]), P. Gr. (Paulo Graves?; Grammatica Anglicana [1594]) などによる穏健な慣用路線へと向かい,これが主として次の世紀に印刷家の支持を受けて定着した.

(3) 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で繰り返し述べてきたように,16世紀は主としてラテン語からおびただしい数の借用語が流入した.ルネサンス期の文人たちの多くが,Sir Thomas Elyot のいうように "augment our Englysshe tongue" を目指したのである.

vernacular としての初期近代英語の抱えた上記3つの問題の背景には,中世から近代への急激な社会変化があった.再び Baugh and Cable (200) を参照すれば,その要因は5つあった.

1. the printing press

2. the rapid spread of popular education

3. the increased communication and means of communication

4. the growth of specialized knowledge

5. the emergence of various forms of self-consciousness about language

まさに,文明開化の音がするようだ.[2012-03-29-1]の記事「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-01-22 Tue

■ #1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 [lexicology][loan_word][french][latin][renaissance][history][register][sociolinguistics][lexical_stratification]

「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]) で英語(の歴史)の民主的な側面を垣間見たが,バランスのとれた視点を保つために,今回は,やはり歴史的な観点から,英語の非民主的な側面を紹介しよう.

英語は,近代英語初期(英国ルネサンス期)に夥しいラテン借用語の流入を経験した (##114,1067,1226).これによって,英語語彙における三層構造が完成されたが,これについては「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]) や「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) で見たとおりである.語彙に階層が設けられたということは,その使用者や使用域 (register) にも対応する階層がありうることを示唆する.もちろん,語彙の階層とその使用に関わる社会的階層のあいだに必然的な関係があるというわけではないが,歴史的に育まれてきたものとして,そのような相関が存在することは否定できない.上層の語彙は「レベル」の高い話者や使用域と結びつけられ,下層の語彙は「レベル」の低い話者や使用域と結びつけられる傾向ははっきりしている.

この状況について,渡部 (244) は,「英語の中の非民主的性格」と題する節で次のように述べている.

人文主義による語彙豊饒化の努力が産んだもう一つの結果は,英語が非民主的な性格を持つようになった,ということであろう.OE時代には王様の言葉も農民の言葉もたいして変りなかったと思われる.上流階級だからと言って特に難かしい単語を使うということは少なかったからである.その状態は Norman Conquest によって,上層はフランス語,下層は英語という社会的二重言語 (social bilingualism) に変ったが,英語が復権すると,英語それ自体の中に,一種の社会的二言語状況を持ち込んだ形になった.その傾向を助長したのは人文主義であって,その点,Purism をその批判勢力と見ることが可能である.事実,聖書をほとんど唯一の読書の対象とする層は,その後近代に至るまでイギリスの民衆的な諸運動とも結びついている.

英語(の歴史)は,ある側面では非民主的だが,別の側面では民主的である.だが,このことは多かれ少なかれどの言語にも言えることだろう.また,言語について言われる「民主性」というのは,「#1318. 言語において保守的とは何か?」 ([2012-12-05-1]) や「#1304. アメリカ英語の「保守性」」 ([2012-11-21-1]) で取り上げた「保守性」と同じように,解釈に注意が必要である.「民主性」も「保守性」も価値観を含んだ表現であり,それ自体の善し悪しのとらえ方は個人によって異なるだろうからだ.それでも,社会言語学的な観点からは,言語の民主性というのはおもしろいテーマだろう.

なお,英語における民主的な潮流といえば,「#625. 現代英語の文法変化に見られる傾向」 ([2011-01-12-1]) や「#1059. 権力重視から仲間意識重視へ推移してきた T/V distinction」 ([2012-03-21-1]) の話題が思い出される.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語の歴史』 大修館,1983年.

2012-09-04 Tue

■ #1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布 [loan_word][lexicology][statistics][emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][latin]

英語史における借用語の最たる話題として,中英語期におけるフランス語彙の著しい流入が挙げられる.この話題に関しては,語彙統計の観点からだけでも,「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) を始めとして,french loan_word statistics のいくつかの記事で取り上げてきた.しかし,語彙統計ということでいえば,近代英語期のラテン借用語を核とする語彙増加のほうが記録的である.

[2009-08-19-1]の記事「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」で言及したが,Görlach は初期近代英語の語彙の著しい増大を次のように評価し,説明している.

The EModE period (especially 1530--1660) exhibits the fastest growth of the vocabulary in the history of the English language, in absolute figures as well as in proportion to the total. (136)

. . . the general tendencies of development are quite obvious: an extremely rapid increase in new words especially between 1570 and 1630 was followed by a low during the Restoration and Augustan periods (in particular 1680--1780). The sixteenth-century increase was caused by two factors: the objective need to express new ideas in English (mainly in fields that had been reserved to, or dominated by, Latin) and, especially from 1570, the subjective desire to enrich the rhetorical potential of the vernacular. / Since there were no dictionaries or academics to curb the number of new words, an atmosphere favouring linguistic experiments led to redundant production, often on the basis of competing derivation patterns. This proliferation was not cut back until the late seventeenth/eighteenth centuries, as a consequence of natural selection or a s a result of grammarians' or lexicographers' prescriptivism. (137--38)

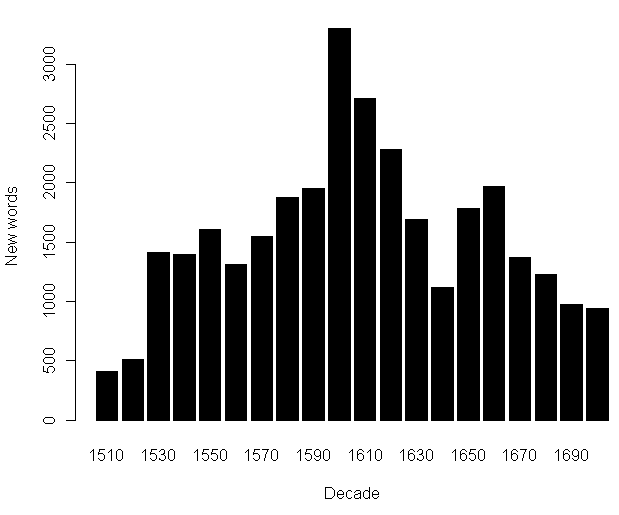

Görlach は,A Chronological English Dictionary に基づいて,次のような語彙統計も与えている (137) .これを図示してみよう.

| Decade | 1510 | 1520 | 1530 | 1540 | 1550 | 1560 | 1570 | 1580 | 1590 | 1600 | 1610 | 1620 | 1630 | 1640 | 1650 | 1660 | 1670 | 1680 | 1690 | 1700 |

| New words | 409 | 508 | 1415 | 1400 | 1609 | 1310 | 1548 | 1876 | 1951 | 3300 | 2710 | 2281 | 1688 | 1122 | 1786 | 1973 | 1370 | 1228 | 974 | 943 |

近代英語期のラテン借用について関連する話題は,「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1]) や emode loan_word lexicology の各記事を参照.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

・ Finkenstaedt, T., E. Leisi, and D. Wolff, eds. A Chronological English Dictionary. Heidelberg: Winter, 1970.

2012-03-29 Thu

■ #1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][emode][renaissance][latin][japanese][linguistic_imperialism][lexical_stratification]

英語と日本語の語彙史は,特に借用語の種類,規模,受容された時代という点でしばしば比較される.語彙借用の歴史に似ている点が多く,その顕著な現われとして両言語に共通する三層構造があることは [2010-03-27-1], [2010-03-28-1] の両記事で触れた.

英語語彙の最上層にあたるラテン語,ギリシア語がおびただしく英語に流入したのは,語初期近代英語の時代,英国ルネッサンス (Renaissance) 期のことである(「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]) , 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) を参照).思想や科学など文化の多くの側面において新しい知識が爆発的に増えるとともに,それを表現する新しい語彙が必要とされたことが,大量借用の直接の理由である.そこへ,ラテン語,ギリシア語の旺盛な造語力という言語的な特徴と,踏み固められた古典語への憧れという心理的な要素とが相俟って,かつての中英語期のフランス語借用を規模の点でしのぐほどの借用熱が生じた.

ひるがえって日本語における洋語の借用史を振り返ってみると,大きな波が3つあった.1つ目は16--17世紀のポルトガル語,スペイン語,オランダ語からの借用,2つ目は幕末から明治期の英独仏伊露の各言語からの借用,3つ目は戦後の主として英語からの借用である.いずれの借用も,当時の日本にとって刺激的だった文化接触の直接の結果である.

英国のルネッサンスと日本の文明開化とは,文化の革新と新知識の増大という点でよく似ており,文化史という観点からは,初期近代英語のラテン語,ギリシア語借用と明治日本の英語借用とを結びつけて考えることができそうだ.しかし,語彙借用の実際を比べてみると,初期近代英語の状況は,明治日本とではなく,むしろ戦後日本の状況に近い.明治期の英語語彙借用は,英語の語形を日本語風にして取り入れる通常の意味での借用もありはしたが,多くは漢熟語による翻訳語という形で受容したのが特徴的である.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) で示した借用のタイプでいえば,importation ではなく substitution が主であったといえるだろう(関連して,##902,903 も参照).また,翻訳語も含めた英語借用の規模はそれほど大きくもなかった.一方,戦後日本の英語借用の方法は,そのままカタカナ語として受容する importation が主であった.また,借用の規模も前時代に比べて著大である.したがって,借用の方法と規模という観点からは,英国ルネッサンスの状況は戦後日本の状況に近いといえる.

中村 (60--61) は,「文芸復興期に英語が社会的に優勢なロマンス語諸語と接触して,一時的にヌエ的な人間を生み出しながら,結局は,ロマンス語を英語の中に取り込んで英語の一部にし得た」と,初期近代英語の借用事情を価値観を込めて解釈しているが,これを戦後日本の借用事情へ読み替えると「戦後に日本語が社会的に優勢な英語と接触して,一時的にヌエ的な人間を生み出しながら,結局は,英語を日本語の中に取り込んで日本語の一部にし得た」ということになる.仮に文頭の「戦後」を「明治期」に書き換えると主張が弱まるように感じるが,そのように感じられるのは,両時代の借用の方法と規模が異なるからではないだろうか.あるいは,「ヌエ的」という価値のこもった表現に引きずられて,私がそのように感じているだけかもしれないが.

価値観ということでいえば,中村氏の著は,英語帝国主義に抗する立場から書かれた,価値観の強くこもった英語史である.主として近代の外面史を扱っており,言語記述重視の英語史とは一線を画している.反英語帝国主義の強い口調で語られており,上述の「ヌエ的」という表現も著者のお気に入りらしく,おもしろい.展開されている主張には賛否あるだろうが,非英語母語話者が英語史を綴ることの意味について深く考えさせられる一冊である.

・ 中村 敬 『英語はどんな言語か 英語の社会的特性』 三省堂,1989年.

2012-03-23 Fri

■ #1061. Coseriu の言語学史の振子 [linguistics][diachrony][history_of_linguistics][renaissance][philosophy_of_language]

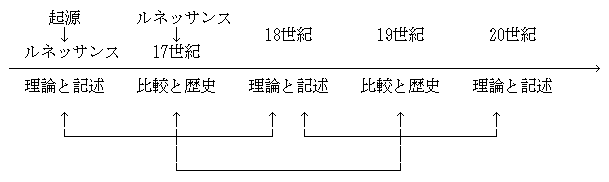

通常,近代言語学史は,Sir William Jones (1746--1794) の1786年の講演と,それに続く比較言語学の発展において始まったとされる([2010-02-03-1]の記事「#282. Sir William Jones,三点の鋭い指摘」を参照).しかし,この18世紀末の契機は,舞台を西洋に限るとしても,より広い歴史的な視野から評価する必要がある.確かに,18世紀末は,初めて継続的に科学的な態度で言語に注目し始めたという点で,言語学史に一線を画する時代だったことは認めてよい.しかし,それ以前にも常に人々は言語に関心を注いできたのである.1786年を境に以前と以後にわける言語学史のとらえ方を「断絶」と呼ぶのであれば,ルーマニア生まれでドイツの言語学者 Coseriu (1921--2002) の言語学史のとらえ方は「振子」,共時的関心と通時的関心のあいだに揺れる振子として表現できるだろう.加賀野井 (65) に紹介されている Coseriu の図式は以下の通り.

この図式によれば,ルネッサンスと19世紀が歴史主義の時代,その前後と狭間の時代が理論・記述主義の時代ということになる.ルネッサンス以前は,ギリシア語やラテン語を規範とする見方や言語哲学が盛んであり,視点は共時的だった.ルネッサンス期は言語どうしの比較や同一言語の異なる時代の比較へ関心が移り,通時的な傾向を示した.18世紀には,近代語の記述文法の研究が進み,ライプニッツの普遍文法などが出たことから,共時的な関心の時代だったといえる.19世紀には比較言語学によって通時的な側面に光が当てられた.そして,20世紀,特にソシュール以降は共時的な言語学が優勢となった.

この図から当然の如く湧き出てくるのは,21世紀は,通時的な関心へと振子が揺り戻すのではないかという予想だ.各時代の関心の交替は,何も言語学の分野だけに限ったことではなく,他の学問領域にも広く共通した思想上の傾向だった.そして,現代のように時代の転換期にあるといわれる時代には,歴史を顧みる傾向が強まるとも言われる.20世紀を駆け抜けた共時言語学の拡散と限界から,そろそろ一休みを入れたい気分にならないとも限らない.振子は,人間の退屈しやすい性質,気分転換を欲する性質を反映していると考えれば,そろそろ揺り戻しがあるかもしれないということも十分に考えられる.

もちろん,Coseriu の振子は,後代から観察した過去の記録にすぎず,未来を決定する力はない.歴史を作るのはそれぞれの時代の人間であり,ここでいえば言語観察者や言語学者である.しかし,20世紀の言語学の達成と発展性を考えると,振子が揺り戻すかもしれないと考えさせる根拠はある.1つは,20世紀の構造言語学や生成文法があまり手をつけずにおいた言語の変異と変化の重要性が,20世紀後半になって認識されてきたこと.2つは,20世紀の共時言語学が上げてきた種々の成果を,かつてソシュールが優先度低しとして棚上げしておいた通時態にも応用してみたくなるのが人情ではないかということ.

また,これは20世紀言語学の成果とは独立した要因ながら,筆者の日頃考えているところだが,英語などの有力言語の世界的な広がり,国際交流に伴う語学熱,情報化社会に裏打ちされた言語の重要性の喧伝などという現代の社会現象が,人々に言語疲れを引き起こす可能性があるのではないかということだ.言語は役に立つ,言語の力は偉大だなどとあまりに喧伝されると疲れてしまう.むしろ,なぜそうなのか,なぜそうなってきたのかという本質的な問題へ向かう傾向が生じるのではないか.

とここまで書きながら,上の議論は,英語史や歴史言語学に肩入れしている筆者の願いにすぎないのかもしれないな,と思ったりもする.21世紀の潮流を見極めたい.

・ 加賀野井 秀一 『20世紀言語学入門』 講談社〈講談社現代新書〉,1995年.

2009-08-19 Wed

■ #114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合 [loan_word][lexicology][statistics][emode][renaissance]

[2009-08-15-1]で現代英語の借用語彙の起源と割合をみたが,今回はその初期近代英語版を.といっても,もととなった数値データ(このページのHTMLソースを参照)はひ孫引き.ここまで他力本願だとせめて提示の仕方を工夫しなければと,Flash にしてみた.このグラフは,Wermser を参照した Görlach (167) を参照した Gelderen の表に基づいて作成したものである.

ここでカバーされている時代は,Görlach いわく,"exhibits the fastest growth of the vocabulary in the history of the English language" (136) であり,借用と造語を合わせて,語彙の成長速度がきわめて著しかった時代である.借用元言語としては,予想通りラテン語とフランス語が合計で8割以上となるが,注目したいのはこの時代を通じて着実に成長していたギリシャ語である.

ルネッサンス ( Renaissance ) のもたらした新しい思想や科学,そして古典の復活により,ギリシャ語やラテン語に由来する無数の専門用語が英語に流入したためである.まさに時代の勢いに比例するかのように,英語の語彙が増大していたのである.

・Wermser, Richard. Statistische Studien zur Entwicklung des englischen Wortschatzes. Bern: Francke Verlag, 1976.

・Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

・Gelderen, Elly van. A History of the English Language. Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 2006. 178.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow