2015-03-16 Mon

■ #2149. 意味借用 [borrowing][loan_word][loan_translation][semantic_change][lexicology][old_norse][semantic_borrowing][christianity]

本ブログのいくつかの記事で 意味借用,semantic_borrowing, あるいは "semantic loan" という用語を使ってきたが,とりたてて話題にしたことはなかったので,今回いくつか例を挙げておきたい.意味借用はときに翻訳借用 (loan_translation) と混同して用いられることがあるが,2つは異なる過程である.翻訳借用においては新たな語彙項目が生み出されるが,意味借用においては既存の語彙項目に新たな語義が追加されるか,それが古い語義を置き換えるかするのみで,新たな語彙項目は生み出されない.ただし,いずれも借用元言語の形態は反映されないという点で共通点がある.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) で説明した Haugen の用語に従えば,いずれも importation ではなく substitution の例ということになる.

英語史における意味借用の典型例の1つに,dream がある.古英語 drēam は "joy, music" (喜び,音楽)の意で用いられたが,対応する古ノルド語の draumr が "vision" (夢)の意をもっていたことにより,その影響で中英語までに「夢」の語義を獲得した.もともとのゲルマン語の段階での原義「(叫び声などによる)惑わし」からの意味発展により「(歓楽による)叫び声,騒ぎ;歓楽;喜び」の系列と「幻影;夢」の系列とが共存していたと考えられるが,後者は古英語へは伝わらなかったようだ.だが実際には,古英語期にも,古ノルド語の影響の強い東中部や北部では「夢」の語義も行われていた形跡がある.

ほかによく知られているものとして,bloom がある.古英語 blōma は "ingot of iron" (塊鉄)を意味したが,古ノルド語 blóm "flower, blossom" (花)の影響で,中英語までに新しい語義を獲得した(ただし,これには異説もある).dwell に相当する古英語単語 dwellan, dwelian は "to lead astray" (迷わせる)で用いられたが,古ノルド語 dvelja (ぐずぐずする;とどまる)より発展的な語義「住む」を借用したとされる.また,「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1]) で触れたように,bread は古英語では brēad "morsel of food" ほどの意味だったが,古ノルド語 brauð "bread" より「パン」の語義を借りてきたようだ (Old Northumbrian に「パン」としての用例がみられる).

古ノルド語からの意味借用の例をいくつか挙げたが,ラテン語からの例としてラテン語 rēs が「集会;こと,もの」の語義をもっていたことから,本来「集会」のみを意味した古英語 þing が「こと,もの」の意味を得たとされる.同様に,古英語の Dryhten "lord" に "the Lord" の語義が追加されたのも,対応するラテン語の dominus の影響だろう(関連して「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]) を参照).古英語における本来語のキリスト教用語には,対応するラテン語の影響で新たに意味を獲得したものが多い (ex. wītega "prophet", þrōþung "suffering", getimbran "edify", cniht "pupil" 等々 (cf. Strang 368--69) .

ほかには,「新しいもの」の意味でフランス語から英語に入ってきたnovel が,その後スペイン語及びイタリア語の対応語から「物語;小説」の意味を取り入れた例などがある.

英語が意味を貸し出した側となっている例もある.フランス語の realizer (はっきり理解する)と introduir(紹介する)のそれぞれの語義は,英語の対応語からの借用である.また,アメリカで話されるポルトガル語の engenho は「技術」を意味したが,英語 engine から「機関車」の意味を借用した.さらに,日本語「触れる」「払う」はそれぞれ物理的な意味のほかに「(問題などに)言及する」「(注意・敬意などを)払う」の意味をもつが,これは対応する touch, pay が両義をもつことからの影響とされる.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2015-03-14 Sat

■ #2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判 [purism][loan_word][french][inkhorn_term][me][lexicology]

16世紀には,ラテン借用語をはじめとしてロマンス諸語などからの借用語がおびただしく英語へ流入した(「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) や「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照).日本語でも明治以降,大量の漢語が作られ,昭和以降は無数のカタカナ語が流入した(「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1]) 及び「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]) を参照).これらの時代の各々において,純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの借用語批判が聞かれた.借用語をむやみやたらに使用するのは控えて,本来語をもっと多く使うべし,という議論である.

英語史においてあまり聞かないのは,中英語期に怒濤のように押し寄せたフランス借用語に対する批判である.「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たとおり,英語はノルマン・コンクェスト後の数世紀間で,歴史上初めて数千語という規模での大量語彙借用を経験してきたが,そのフランス借用語への批判はなかったのだろうか.

確かにルネサンス期のインク壺語批判ほどは目立たないが,中英語におけるフランス借用語批判がまったくなかったわけではない.Ranulph Higden (c. 1280--1364) によるラテン語の Polychronicon を1387年に英訳した John of Trevisa (1326--1402) は,ある一節で,古ノルド語とともにフランス語からの借用語の無分別な使用について苦情を呈している.Crystal (186) からの引用を再現しよう.

by commyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys apeyred, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbittyng.

同様に,Richard Rolle of Hampole (1290?--1349.) による Psalter (a1350) でも,"seke no strange Inglis" (見知らぬ英語は使わない)とフランス借用語に対して暗に不快感を示しているし,15世紀に Polychronicon を英訳した Osbern Bokenham (1393?--1447?) も,フランス語が英語を野蛮にしたと非難している (Crystal 186) .しかし,彼らとて,自らの著書のなかで,洗練されたフランス借用語を用いていたことはいうまでもない.

このように中英語期のフランス借用語への純粋主義的な非難はいくつか確認されるが,後世の激しいインク壺語批判に比べれば単発的であり,特に大きな潮流を形成しなかったようだ.英語自体がまだ一国の言語としておぼつかない地位にあって,英語の本来語への思慕や借用語の嫌悪という純粋主義的な態度が世の注目を浴びるには,まだ時代が早かったものと思われる.それでも,この中英語期の早熟な純粋主義的批判は,後世の苛烈な批判の前段階として,確かに英語史上に位置づけられるものではあるだろう.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2015-01-05 Mon

■ #2079. fusion と mixture [contact][borrowing][loan_word][loan_translation][bilingualism][substratum_theory][typology][register][lexical_stratification]

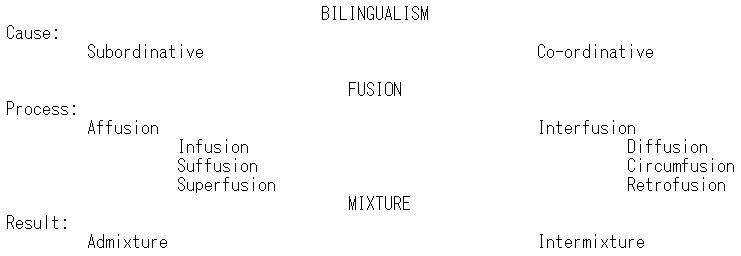

「#2061. 発話における干渉と言語における干渉」 ([2014-12-18-1]) で念を押したように,語の借用 (borrowing) は過程であり,借用語 (loanword) は結果である.Weinreich は明示的にこの区別をつける論者は少なかったと述べているが,Roberts という研究者がより早くこの区別について論じている.Roberts (31--32) は,言語接触の過程を "fusion" と呼び,結果としての状態を "mixture" と呼び分けた.また,Roberts は "fusion" と "mixture" をそれぞれ細分化するとともに,そのような過程や結果の前段階にある2言語使用状況のタイプを2つに分け,全体として言語接触の類型論というべきものを提起している.以下,Roberts (32) の図式を再現しよう.

だが,正直いうと論文を読みながら非常に理解しにくい図式だと感じた.多くの用語が立ち並んでいるが,それぞれの歴史的な事例とそれらの間の相互の関係がとらえにくいのだ.BILINGUALISM → FUSION → MIXTURE という時間的な相の提示と後者2過程の峻別は評価できるとしても,それ以外については用語が先走っている印象であり,内容どうしの関係が不明瞭だ.Roberts (31--32) にそのまま語ってもらおう.

When a bilingual situation ends, the surviving language (that is, the language whose grammar prevails) is colored in greater or less degree by the perishing language (that is, the language whose grammar succumbs). The extent of this coloring depends upon the relationship of the two languages during the antecedent bilingualism. Subordinative bilingualism results in admixture; a portion of the weaker language is added to the stronger, which still retains both its grammatical and its lexical integrity. Co-ordinative bilingualism results in intermixture; virtually the entire vocabulary of the weaker language is swallowed up by the stronger, which thereby loses its lexical, though not its grammatical, integrity.

The words admixture and intermixture, as here used, denote accomplished situations, the results of processes. To designate the generative processes, the terms affusion and interfusion, corresponding respectively to admixture and intermixture, are proposed. Affusion has three modalities: infusion, suffusion, and superfusion. Interfusion has three stages or temporalities: diffusion, circumfusion, and retrofusion.

Affusion から見ていくと,Infusion は通常の語の借用に相当する.Suffusion は,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) の唱える基層言語からの言語的影響に相当する.Superfusion は翻訳借用 (loan_translation) に相当する.importation と substitution という対立軸と,意識的な干渉と無意識的な干渉という対立軸がごたまぜになったような分類だ.

次に Interfusion に目を向けると,Diffusion は本来語彙と借用語彙が使用域に関して分化する過程を指している.英語語彙における語種別の三層構造などの生成にみられる過程を想像すればよいだろう.その Interfusion の段階からさらに進むと,Circumfusion の段階となる.ここでは例えば内容語はすべてフランス・ラテン借用語であっても,それらを取り巻く機能語は本来語となるような状況が生み出される.次に,Retrofusion はソース言語からの一種の「復讐」の過程であり,フランス語の語法の影響を受けて house beautiful, knights templars, sufficient likelihood, nocturnal darkness などの表現を生み出す過程に相当する.

Roberts は2言語使用 (bilingualism) の基礎理論を打ち立てようという目的でこの論文を書いたようだが,残念ながらうまくいっているようには思えない.より説得力のある言語接触の類型論としては,「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) と「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]) で紹介した Thomason and Kaufman によるモデルが近年ではよく知られている.

借用に関する過程と結果の区別については「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#904. 借用語を共時的に同定することはできるか」 ([2011-10-18-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1]) も参照.また,関連して「#2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因」 ([2014-12-24-1]) の記事とそこに張ったリンクも参照されたい.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

・ Roberts, Murat H. "The Problem of the Hybrid Language". Journal of English and Germanic Philology 38 (1939): 23--41.

2014-12-29 Mon

■ #2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非 [lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][register][synonym][romancisation][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙の三層構造について「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]),「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) など,多くの記事で言及してきた.「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]) でみたように,語彙の三層構造ゆえに英語は非民主的な言語であるとすら言われることがあるが,英語語彙のこの特徴は見方によっては是とも非となる類いのものである.

Jespersen (121--39) がその是と非の要点を列挙している.まず,長所から.

(1) 英仏羅語に由来する類義語が多いことにより,意味の "subtle shades" が表せるようになった.

(2) 文体的・修辞的な表現の選択が可能になった.

(3) 借用語には長い単語が多いので,それを使う話者は考慮のための時間を確保することができる.

(4) ラテン借用語により国際性が担保される.

まず (1) と (2) は関連しており,表現力の大きさという観点からは確かに是とすべき項目だろう.日本語語彙の三層構造と比較すれば,表現者にとってのメリットは実感されよう.しかし,聞き手や学習者にとっては厄介な特徴ともいえ,その是非はあくまで相対的なものであるということも忘れてはならない.(3) はおもしろい指摘である.非母語話者として英語を話す際には,ミリ秒単位(?)のごく僅かな時間稼ぎですら役に立つことがある.長い単語で時間稼ぎというのは,状況にもよるが,戦略としては確かにあるのではないか.(4) はラテン借用語だけではなくギリシア借用語についても言えるだろう.関連して「#512. 学名」 ([2010-09-21-1]) や「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1]) も参照されたい.

次に,Jespersen が挙げている短所を列挙する.

(5) 不必要,不適切なラテン借用語の使用により,意味の焦点がぼやけることがある.

(6) 発音,綴字,派生語などについて記憶の負担が増える.例えば,「#859. gaseous の発音」 ([2011-09-03-1]) の各種のヴァリエーションの問題や「#573. 名詞と形容詞の対応関係が複雑である3つの事情」 ([2010-11-21-1]) でみた labyrinth の派生形容詞の問題などは厄介である.

(7) 科学の日常化により,関連語彙には国際性よりも本来語要素による分かりやすさが求められるようになってきている.例えば insomnia よりも sleeplessness のほうが分かりやすく有用であるといえる.

(8) 非本来語由来の要素の導入により,派生語間の強勢位置の問題が生じた (ex. Cánada vs Canádian) .

(9) ラテン語の複数形 (ex. phenomena, nuclei) が英語へもそのまま持ち越されるなどし,形態論的な統一性が崩れた.

(10) 語彙が非民主的になった.

是と非とはコインの表裏の関係にあり,絶対的な判断は下しにくいことがわかるだろう.結局のところ,英語の語彙構造それ自体が問題というよりは,それを使用者がいかに使うかという問題なのだろう.現代英語の語彙構造は,各時代の言語接触などが生み出してきた様々な語彙資源の歴史的堆積物にすぎず,それ自体に良いも悪いもない.したがって,そこに民主的あるいは非民主的というような評価を加えるということは,評価者が英語語彙を見る自らの立ち位置を表明しているということである.Jespersen (139) は次の総評をくだしている.

While the composite character of the language gives variety and to some extent precision to the style of the greatest masters, on the other hand it encourages an inflated turgidity of style. . . . [W]e shall probably be near the truth if we recognize in the latest influence from the classical languages 'something between a hindrance and a help'.

日本語において明治期に大量に生産された(チンプン)漢語や20世紀にもたらされた夥しいカタカナ語にも,似たような評価を加えることができそうだ(「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先を参照).

英語という言語の民主性・非民主性という問題については「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で取り上げたので,そちらも参照されたい.また,英語語彙のロマンス化 (romancisation) に関する評価については「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1]) や「#395. 英語のロマンス語化についての評」 ([2010-05-27-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2014-12-26 Fri

■ #2069. 言語への忠誠,言語交替,借用方法 [loan_translation][purism][borrowing][contact][language_shift][loan_word]

他言語から語を借用する場合,形態をおよそそのまま借り入れる importation と,自言語へ翻訳して借り入れる substitution が区別される.一般に前者は借用語 (loanword) と呼ばれ,後者は翻訳借用(語) (loan_translation) と呼ばれる.細かい分類や用語は Haugen に依拠して書いた記事「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) に譲るが,この2種類の借用方法が記号論的に大いに相違していることは明らかである.

2つの借用方法を区別した上で問題となるのは,個別言語の語彙借用の個々の事例において,いずれの方法で借用するかを決定しているのはいかなる要因かということだ.言語によって,あるいは時代によって,いずれかが好まれるというのは英語史,日本語史,他の言語の歴史でも確認されており,個々の傾向があることは否定できない.だが,同言語の同時代の個々の借用の事例をみると,あるものについては importation だが,別のものについては substitution であるといったケースがある.これらについては個別に言語内的・外的な要因を探り,それぞれの要因の効き具合を確かめる必要があるのだろうが,実際上は確認しがたく,表面的には借用方法の選択はランダムであるかのようにみえる.また,importation と substitution を語のなかで半々に採用した「赤ワイン」のような loanblend の事例も見られ,借用方法の決定を巡る議論はさらに複雑になる.この辺りの問題については,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]),「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]),「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1]),「#2064. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (1)」 ([2014-12-21-1]) でも部分的に触れてきた通りだ.

importation ではなく substitution を選択する言語外的な要因として真っ先に思い浮かぶのは,受け入れ言語の話者(集団)が抱いているかもしれない母語への忠誠心や言語的純粋主義だろう (cf. 「#2068. 言語への忠誠」 ([2014-12-25-1])) .自言語への愛着が強ければ強いほど,他言語からの自言語への目に見える影響は排除したいと思うのが普通だろう.それを押してでも語彙を借用するということになれば,そのまま借用ではなく翻訳借用がより好まれるのも自然である.一方,そのような忠誠心が希薄であれば,そのまま借用への抵抗感も薄いだろう.

他に考えられるパラメータとしては,借用の背景にある言語接触が安定した2言語使用状況なのか,あるいは話者の言語交替を伴うものなのかという区別がある.前者では substitution が多く,後者では importation が多いという仮説だ.Weinreich (109) は ". . . language shifts are characterized by word transfers, while loan translations are the typical mark of stable bilingualism without a shift" という可能性に言及している.

この点で,「#1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点」 ([2013-10-21-1]) で示した観点を振り返ると興味深い.古英語のラテン語借用では substitution も多かったが,中英語のフランス語借用と初期近代英語のラテン語借用では importation が多かった.そして,後者の2つの語彙借用の波は,ある種の「安定的な2言語使用状況」が崩れ,ある種の「言語交替」が起こり始めたちょうどそのタイミングで観察されるのである.上の仮説では「安定的な2言語使用状況」と「言語交替」は対置されているものの,実際には連続体であり,明確な境を設けることは難しいという問題はある.しかし,この仮説のもつ含蓄は大きい.借用方法という記号論的・言語学的な問題と,言語への忠誠や言語交替のような社会言語学的な問題とをリンクさせる可能性があるからだ.今後もこの問題には関心を寄せていきたい.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-12-24 Wed

■ #2067. Weinreich による言語干渉の決定要因 [contact][borrowing][loan_word][causation]

言語干渉の要因や尺度について,これまで以下の記事で様々に考えてきた.

・ 「#430. 言語変化を阻害する要因」 ([2010-07-01-1])

・ 「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1])

・ 「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1])

・ 「#934. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語 (2)」 ([2011-11-17-1])

・ 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])

・ 「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1])

・ 「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1])

・ 「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1])

・ 「#2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約」 ([2014-10-29-1])

・ 「#2064. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (1)」 ([2014-12-21-1])

・ 「#2065. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (2)」 ([2014-12-22-1])

今回は,言語干渉を促進する・阻害する構造的・非構造的要因を一覧にしてまとめた Weinreich (64--65) による表を掲げよう.PDF版はこちら.これを眺めながら,言語変化一般と同様に言語干渉による変化も,言語内的・外的の両要因によって条件付けられている可能性が常にあることを再認識したい.関連して「#1986. 言語変化の multiple causation あるいは "synergy"」 ([2014-10-04-1]) 及び multiple causation の各記事も参照されたい.

| FORM OF INTERFERENCE | EXAMPLE | STRUCTURAL | NON-STRUCTURAL | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STIMULI | RESISTANCE FACTORS | STIMULI | RESISTANCE FACTORS | ||

| All interference | Any points of difference between two systems | Stability of systems; requirements of intelligibility | Social value of source (model, primary) language; bilingual interlocutors; affective speech; individual propensity for speech mixture; etc. | Social value of recipient language; intolerance of interference; puristic attitudes toward recipient (secondary) language; loyalty to mother-tongue; unilingual interlocutors; etc. | |

| Phonic | |||||

| Under-differentiation of phonemes | /d/ and /t/ not differentiated | Absence of corresponding distinctions in primary language | Functional yield of the distinction | --- | Loyalty to secondary language |

| Over-differentiation of phonemes | [k] and [kh] treated as separate phonemes | Presence of distinction (only) in primary language | --- | --- | --- |

| Reinterpretation of relevant features | Voiceless /p/ treated as phonemically tense and only concomitantly voiceless | Different phonemic systems | Existence of appropriate holes in the pattern | --- | --- |

| Phone substitution | [r] for [R] where there is only one trill phoneme | Different pronunciations equivalent phonemes | Danger of confusion with another phoneme | Social value of primary language | Loyalty to secondary language |

| Integration of loanwords | English /rajs/ into Hawaiian /lɑiki/ | Difference in phonemic systems; homogeneous but different type of word structure in recipient language | Potential homonymy (?) | Intolerance of recognizable loanwords; unilingualism of speaker | Social value of source language |

| Grammatical | |||||

| Transfer of morphemes | Slovak-German in Pressburg-u; Yiddish-English job-shmob | Congruent systems, much common vocabulary, relatively unbound morphemes, greater phonemic bulk | Non-congruent systems; complicated functions of morphemes | Affectiveness of categories | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Transfer of grammatical relations | German-English I come soon home | Different relation patterns | Conflict with existing relations | Affectiveness of categories | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Change in function of "indigenous" morpheme or category | German-English how long are you here? | Greater explicitness of model (usually) | --- | --- | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Abandonment of obligatory categories | Loss of old French tense system in Creole | Very different grammatical systems | --- | Makeshift language | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Integration of loanwords | English change into Amer. Portuguese chinjar | Homogeneous word structure in recipient language | --- | Intolerance of recognizable loanwords; unilingualism of speaker | Social value of source language |

| Lexical | |||||

| Lexical interference as such | --- | Structural weak points in recipient vocabulary, need to match differentiations in source language | Existence of adequate vocabulary | Lexical inadequacy in face of innovations; oblivion of infrequent words, need for synonyms, prestige of source language, stylistic effect of mixture | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Outright transfer of words (rather than semantic extension) | German Telephon rather than Fernsprecher | Congenial form of word; possibility of polysemy (?) | Potential homonymy (?); uncongenial word form | Bilingualism of interlocutors | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Phonic adjustment of cognates | Spanish /euˈropa/ into /juˈropa/ on English model | Economy of a single form | --- | --- | Loyalty to recipient language |

| Specialized retention of an "indigenous" word after borrowing of an equivalent | French chose, retained and distinguished from cause | No confusion in semantemes | Elimination of superfluous terms | --- | --- |

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-12-22 Mon

■ #2065. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (2) [contact][borrowing][loan_word][anthropology][sociolinguistics][speed_of_change][exaptation]

昨日の記事「#2064. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (1)」 ([2014-12-21-1]) に続き,言語項と文化項の借用にみられる共通点について.言語も文化の一部とすれば,借用に際しても両者の間に共通点があることは不思議ではないかもしれない.ただし,あまりこのような視点からの比較はされてこなかったと思われるので,この件についての言及をみつけると,なるほどと感心してしまう.

昨日と同様に,Weinreich は Linton (Linton, Ralph, ed. Acculturation in Seven American Indian Tribes. New York, 1940) に依拠しながら,さらなる共通点を2つほど指摘している.1つは,既存の語の同義語が他言語から借用される場合に関わる.すでに自言語に存在する語の同義語が他言語から借用される場合には,(1) 両語の意味に混同が生じる,(2) 借用語が本来語を置き換える,(2) 両方の語が意味を違えながら共存する,のいずれかが生じるとされる.(3) は道具などの文化的な項目の借用についても言えることではないか.Weinreich (55fn) 曰く,

Similarly in culture contact. "The substitution of a new culture element," Linton writes . . ., "by no means always results in the complete elimination of the old one. There are many cases of partial . . . replacement. . . . Stone knives may continue to be used for ritual purposes long after the metal ones have superseded them elsewhere."

既存の項が役割を特化させるなどしながらあくまで生き残るという過程は,文法化研究などで注目されている exaptation の例にも比較される (cf. 「#1586. 再分析の下位区分」 ([2013-08-30-1])) .

言語項と文化項の借用にみられる2つ目の共通点は,借用を促進する要因と阻害する要因に関するものである.言語の借用尺度の決定に関与する要因は,構造的(言語内的)なものと非構造的(言語外的)なものに2分される.前者は言語体系への統合の度合いに関わり,後者は例えば2言語使用者の習慣,発話の状況,言語接触の社会文化的環境などを含む(「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) も参照).Weinreich (66--67fn)は,文化人類学者の洞察に触れながら,文化項の借用にも同様に構造的・非構造的な要因が認められるとしている.

Distinctions parallel to those between stimuli and resistance, structural and non-structural factors, occur implicitly in studies of acculturation, too. Thus, Redfield, Linton, and Herskovits . . . distinguish culture traits "presented" (=stimuli) from those "selected" in acculturation situations, and stress the "significance of understanding the resistance to traits as well as the acceptance of them." They also name "congruity of existing culture-patterns" as a reason for a selection of traits; this corresponds to structural stimuli in language contact. When Linton observes . . . that "new things are borrowed on the basis of their utility, compatibility with preëxisting culture patterns, and prestige associations," his three factors are equivalent, roughly, to structural stimuli of interference, structural resistance, and nonstructural stimuli, respectively. Kroeber . . . devotes a special discussion to resistance against diffusion. Resistance to cultural borrowing is also the subject of a separate article by Devereux and Loeb . . ., who distinguish between "resistance to the cultural item"---corresponding roughly to structural resistance in language contact---and "resistance to the lender." These authors also discuss resistance ON THE PART OF the "lender," e.g. the attempts of the Dutch to prevent Malayans, by law, from learning the Dutch language. No equivalent lender's resistance seems to operate in language contact, unless the inconspicuousness of a strongly varying, phonemically slight morpheme with complicated grammatical functions be considered as a point of resistance to transfer within the source language . . . .

このような文化と言語における借用の比較は,言語学と文化人類学との学際的な研究課題,人類言語学の研究テーマになるだろう.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-12-21 Sun

■ #2064. 言語と文化の借用尺度 (1) [contact][borrowing][loan_word][anthropology][sociolinguistics][loan_translation]

言語項の借用尺度 (scale of adoptability) について,「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#934. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語 (2)」 ([2011-11-17-1]),「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1]),「#2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約」 ([2014-10-29-1]) などで取り上げてきた.理論的には,語彙でいえば機能語よりも内容語が,抽象的な意味をもつ語よりは具体的な意味をもつ語のほうが言語間での借用が容易である.このことは確かに直感にも合うし,ある程度は実証されてもいる.

Whitney, Haugen, Moravcsik, Thomason and Kaufman などと同じ借用への関心から Weinreich (35) も言語項の借用尺度について考究しているが,向き合い方はやや慎重である.

It may be possible to range the morpheme classes of a language in a continuous series from the most structurally and syntagmatically integrated inflectional ending, through such "grammatical words" as prepositions, articles, or auxiliary verbs, to full-fledged words like nouns, verbs, and adjectives, and on to independent adverbs and completely unintegrated interjections. Then this hypothesis might be set up: The fuller the integration of the morpheme, the less likelihood of its transfer. A scale of this type was envisaged by Whitney in 1881 . . . and by many linguistics since. Haugen . . . discusses it as the "scale of adoptability," without, perhaps, sufficiently emphasizing its still hypothetical nature as far as bilinguals' speech is concerned. It should be clear how much painstaking observation and analysis is necessary before this hypothesis can be put to the test.

しかし,Weinreich がこの問題に関して面目躍如たる貢献をしているのは,言語項の借用と文化項の借用 (acculturation) の間の類似性を指摘していることだ.上の引用と同ページの脚注に,次のようにある.

Students of acculturation face a similar problem---almost equally unexplored---of rating culture elements according to their transferability. "It seems," says Linton in a tentative remark . . ., "that, other things [e.g. prestige associations] being equal, certain sorts of culture elements are more easily transferable than others. Tangible objects such as tools, utensils, or ornaments are taken over with great ease, in fact they are usually the first things transferred in contact situations. . . . The transfer of elements which lack the concreteness and ready observability of objects is the most difficult of all. . . . In general, the more abstract the element, the more difficult the transfer."

言語項にせよ文化項にせよ,その具体性と借用可能性が関連していそうだというところまでは察しがついた.次なる問題は,このことと借用の方式(importation か substitution かという問題)との間にも何らかの相関関係がありうるだろうかということだ.例えば,具体的な言語項や文化項は,受け入れる際に「翻訳」せずにモデルのまま取り入れる傾向 (importation) があったり,逆に抽象的なものは「翻訳」して取り込む傾向 (substitution or loan_translation) があったりするだろうか.あるいは,むしろ逆の傾向を示すものだろうか,等々.

借用における importation と substitution については,「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]),「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]),「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]),「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1]) などで扱ってきたが,言語の問題にとどまらず,より大きな文化の問題にもなりうるということかもしれない.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-12-18 Thu

■ #2061. 発話における干渉と言語における干渉 [contact][borrowing][bilingualism][loan_word][lexical_diffusion][terminology][language_change]

語の借用 (borrowing) と借用語 (loanword) とは異なる.前者は過程であり,後者は結果である.両者を区別する必要について,「#900. 借用の定義」 ([2011-10-14-1]),「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]),「#904. 借用語を共時的に同定することはできるか」 ([2011-10-18-1]),「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1]) で扱ってきた通りである.

言語接触の分野で早くからこの区別をつけることを主張していた論者の1人に,Weinreich (11) がいる.

In speech, interference is like sand carried by a stream; in language, it is the sedimented sand deposited on the bottom of a lake. The two phases of interference should be distinguished. In speech, it occurs anew in the utterances of the bilingual speaker as a result of his personal knowledge of the other tongue. In language, we find interference phenomena which, having frequently occurred in the speech of bilinguals, have become habitualized and established. Their use is no longer dependent on bilingualism. When a speaker of language X uses a form of foreign origin not as an on-the-spot borrowing from language Y, but because he has heard it used by others in X-utterances, then this borrowed element can be considered, from the descriptive viewpoint, to have become a part of LANGUAGE X.

過程としての借用と結果としての借用語は言語干渉 (interference) の2つの異なる局面である.前者は parole に,後者は langue に属すると言い換えてもよいかもしれない.続けて Weinreich は同ページの脚注で,上の区別の重要性を認識している先行研究は少ないとしながら,以下の研究に触れている.

The only one to have drawn the theoretical distinction seems to be Roberts (450, 31f.), who arbitrarily calls the generative process "fusion" and the accomplished result "mixture." In anthropology, Linton (312, 474) distinguishes in the introduction of a new culture element "(1) its initial acceptance by innovators, (2) its dissemination to other members of the society, and (3) the modifications by which it is finally adjusted to the preexisting culture matrix."

特に人類学者 Linton からの引用部分に注目したい.(言語項を含むと考えられる)文化的要素の導入には3段階が区別されるという指摘があるが,これは「#1466. Smith による言語変化の3段階と3機構」 ([2013-05-02-1]) でみた (1) potential for change, (3) diffusion, (2) implementation に緩やかに対応しているように思われる.借用は,借用語の受容,拡大,定着という段階を経ながら進行していくという見方だ.言語項の借用については,このような複層的で動的なとらえ方が必要である."dissemination" や "diffusion" のステージと関連して,語彙拡散 (lexical_diffusion) の各記事,とりわけ「#855. lexical diffusion と critical mass」 ([2011-08-30-1]) を参照.

・ Weinreich, Uriel. Languages in Contact: Findings and Problems. New York: Publications of the Linguistic Circle of New York, 1953. The Hague: Mouton, 1968.

2014-11-19 Wed

■ #2032. 形容詞語尾 -ive [etymology][suffix][french][loan_word][spelling][pronunciation][verners_law][consonant][stress][gsr][adjective]

フランス語を学習中の学生から,こんな質問を受けた.フランス語では actif, effectif など語尾に -if をもつ語(本来的に形容詞)が数多くあり,男性形では見出し語のとおり -if を示すが,女性形では -ive を示す.しかし,これらの語をフランス語から借用した英語では -ive が原則である.なぜ英語はフランス語からこれらの語を女性形で借用したのだろうか.

結論からいえば,この -ive はフランス語の対応する女性形語尾 -ive を直接に反映したものではない.英語は主として中英語期にフランス語からあくまで見出し語形(男性形)の -if の形で借用したのであり,後に英語内部での音声変化により無声の [f] が [v] へ有声化し,その発音に合わせて -<ive> という綴字が一般化したということである.

中英語ではこれらのフランス借用語に対する優勢な綴字は -<if> である.すでに有声化した -<ive> も決して少なくなく,個々の単語によって両者の間での揺れ方も異なると思われるが,基本的には -<if> が主流であると考えられる.試しに「#1178. MED Spelling Search」 ([2012-07-18-1]) で,"if\b.*adj\." そして "ive\b.*adj\." などと見出し語検索をかけてみると,数としては -<if> が勝っている.現代英語で頻度の高い effective, positive, active, extensive, attractive, relative, massive, negative, alternative, conservative で調べてみると,MED では -<if> が見出し語として最初に挙がっている.

しかし,すでに後期中英語にはこの綴字で表わされる接尾辞の発音 [ɪf] において,子音 [f] は [v] へ有声化しつつあった.ここには強勢位置の問題が関与する.まずフランス語では問題の接尾辞そのもに強勢が落ちており,英語でも借用当初は同様に接尾辞に強勢があった.ところが,英語では強勢位置が語幹へ移動する傾向があった (cf. 「#200. アクセントの位置の戦い --- ゲルマン系かロマンス系か」 ([2009-11-13-1]),「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1]),「#861. 現代英語の語強勢の位置に関する3種類の類推基盤」 ([2011-09-05-1]),「#1473. Germanic Stress Rule」 ([2013-05-09-1])) .接尾辞に強勢が落ちなくなると,末尾の [f] は Verner's Law (の一般化ヴァージョン)に従い,有声化して [v] となった.verners_law と子音の有声化については,特に「#104. hundred とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2009-08-09-1]) と「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) を参照されたい.

上記の音韻環境において [f] を含む摩擦音に有声化が生じたのは,中尾 (378) によれば,「14世紀後半から(Nではこれよりやや早く)」とある.およそ同時期に,[s] > [z], [θ] > [ð] の有声化も起こった (ex. is, was, has, washes; with) .

上に述べた経緯で,フランス借用語の -if は後に軒並み -ive へと変化したのだが,一部例外的に -if にとどまったものがある.bailiff (執行吏), caitiff (卑怯者), mastiff (マスチフ), plaintiff (原告)などだ.これらは,古くは [f] と [v] の間で揺れを示していたが,最終的に [f] の音形で標準化した少数の例である.

以上を,Jespersen (200--01) に要約してもらおう.

The F ending -if was in ME -if, but is in Mod -ive: active, captive, etc. Caxton still has pensyf, etc. The sound-change was here aided by the F fem. in -ive and by the Latin form, but these could not prevail after a strong vowel: brief. The law-term plaintiff has kept /f/, while the ordinary adj. has become plaintive. The earlier forms in -ive of bailiff, caitif, and mastiff, have now disappeared.

冒頭の質問に改めて答えれば,英語 -ive は直接フランス語の(あるいはラテン語に由来する)女性形接尾辞 -ive を借りたものではなく,フランス語から借用した男性形接尾辞 -if の子音が英語内部の音韻変化により有声化したものを表わす.当時の英語話者がフランス語の女性形接尾辞 -ive にある程度見慣れていたことの影響も幾分かはあるかもしれないが,あくまでその関与は間接的とみなしておくのが妥当だろう.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

2014-10-29 Wed

■ #2011. Moravcsik による借用の制約 [contact][borrowing][loan_word][implicational_scale]

昨日の記事「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) で引用した Moravcsik は,どのような言語項が借用されやすいかなど,借用の制約について理論的な考察を加えている.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1]) でも取り上げた,いわゆる借用尺度 (scale of adoptability) の問題である.

Moravcsik (110--13) は,借用の制約の具体例として7項目を挙げている.以下,制約の項目の部分のみを箇条書きで抜き出そう.

(1) No non-lexical language property can be borrowed unless the borrowing language already includes borrowed lexical items from the same source language.

(2) No member of a constituent class whose members do not serve as domains of accentuation can be included in the class of properties borrowed from a particular source language unless some members of another constituent class are also so included which do serve as domains of accentuation and which properly include the same members of the former class.

(3) No lexical item that is not a noun can belong to the class of properties borrowed from a language unless this class also includes at least one noun.

(4) A lexical item whose meaning is verbal can never be included in the set of borrowed properties.

(5) No inflectional affixes can belong to the set of properties borrowed from a language unless at least one derivational affix also belongs to the set.

(6) A lexical item that is of the "grammatical" type (which type includes at least conjunctions and adpositions) cannot be included in the set of properties borrowed from a language unless the rule that determines its linear order with respect to its head is also so included.

(7) Given a particular language, and given a particular constituent class such that at least some members of that class are not inflected in that language, if the language has borrowed lexical items that belong to that constituent class, at least some of these must also be uninflected.

いずれの制約ももってまわった言い方であり,やけに複雑そうな印象を与えるが,それぞれ易しいことばで言い換えれば難しいことではない.直感的にさもありなんという制約であり,古くは Haugen が,新しくは Thomason and Kaufman が指摘している類いの含意尺度 (implicational_scale) への言及である.(1) は,語彙項目の借用がなく,非語彙項目(文法項目など)のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(2) は,拘束形態素が,それを含む自由形(典型的には語)から独立して借用されることはないという制約.(3) は,名詞の借用がなく,非名詞のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(4) は,動詞が音形と意味をそのまま保ったまま借用されることはないという制約(例えば,日本語の「ボイコットする」などはサ変動詞の支えで動詞化しているのであり,英語の動詞 boycott がそのまま動詞として用いられているわけではない).(5) は,派生形態素の借用がなく,屈折形態素のみが借用されることはありえないという制約.(6) は,例えば前置詞の音形と意味のみが借用され,前置という統語規則自体は借用されない,ということはありえないという制約(つまり,前置詞を借用しておきながら,後置詞として用いるというような例はないとされる).(7) は,自言語でも無屈折形が存在するにもかかわらず,他言語からの借用語は一切無屈折形ではありえない,という例はないという制約.

Moravcsik は以上の制約を経験的に導き出されたものとしているから,その後の研究で反例が見つかるならば変更や訂正が必要となるはずである.いずれにせよ Moravcsik の提案は極めて構造言語学的な,言語内的な発想に基づいた制約であり,現在の言語接触研究で重視されている借用者個人の心理やその集団の社会言語学的な特性などの観点はほぼ完全に捨象されている(cf. 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1])).時代といえば時代なのだろう.しかし,言語内的な制約への関心が薄れてきたとはいうものの,構造的な視点にも改善と進歩の余地は残されているのではないかとも思う.類型論の立場から,含意尺度の記述を精緻化していくこともできそうだ.

・ Moravcsik, Edith A. "Language Contact." Universals of Human Language. Ed. Joseph H. Greenberg. Vol. 1. Method & Theory. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1978. 93--122.

2014-10-17 Fri

■ #1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」 [japanese][katakana][kanji][lexicology][lexicography][inkhorn_term][loan_word][waseieigo][link]

ヨミウリ・オンライン(読売新聞)内に,中央大学が発信するニュースサイト Chuo Online がある.そのなかの 教育×Chuo Online へ寄稿した「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」と題する私の記事が,昨日(2014年10月16日)付で公開されたので,関心のある方はご参照ください.ちょうど今期の英語史概説の授業で,この問題の英語版ともいえる初期近代英語期のインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) を巡る論争について取り上げる矢先だったので,とてもタイムリー.数週間後に記事の英語版も公開される予定. *

上の投稿記事に関連する内容は本ブログでも何度か取り上げてきたものなので,関係する外部リンクと合わせて,この機会にリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 文化庁による平成25年度「国語に関する世論調査」

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合」 ([2011-08-20-1])

・ 「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1])

・ 「#1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)」 ([2012-08-11-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1])

・ 「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#1616. カタカナ語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-29-1])

・ 「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1])

・ 「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1])

・ 「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) とそこに張ったリンク集

・ 「#1869. 日本語における仏教語彙」 ([2014-06-09-1])

・ 「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1])

・ 「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1])

(後記 2014/10/30(Thu):英語版の記事はこちら. *)

2014-10-06 Mon

■ #1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2) [loan_word][borrowing][contact][pragmatics][methodology][bilingualism][code-switching][discourse_marker]

Treffers-Daller の借用に関する論文および Meeuwis and Östman の言語接触に関する論文を読み,「#1778. 借用語研究の to-do list」 ([2014-03-10-1]) に付け足すべき項目が多々あることを知った.以下に,いくつか整理してみる.

(1) 借用には言語変化の過程の1つとして考察すべき諸側面があるが,従来の研究では主として言語内的な側面が注目されてきた.言語接触の話題であるにもかかわらず,言語外的な側面の考察,社会言語学的な視点が足りなかったのではないか.具体的には,借用の契機,拡散,評価の研究が遅れている.Treffers-Dalle (17--18) の以下の指摘がわかりやすい.

. . . researchers have mainly focused on what Weinreich, Herzog and Labov (1968) have called the embedding problem and the constraints problem. . . . Other questions have received less systematic attention. The actuation problem and the transition problem (how and when do borrowed features enter the borrowing language and how do they spread through the system and among different groups of borrowing language speakers) have only recently been studied. The evaluation problem (the subjective evaluation of borrowing by different speaker groups) has not been investigated in much detail, even though many researchers report that borrowing is evaluated negatively.

(2) 借用研究のみならず言語接触のテーマ全体に関わるが,近年はインターネットをはじめとするメディアの発展により,借用の起こる物理的な場所の存在が前提とされなくなってきた.つまり,接触の質が変わってきたということであり,この変化は借用(語)の質と量にも影響を及ぼすだろう.

Due to modern advances in telecommunication and information technology and to more extensive traveling, members within such groupings, although not being physically adjacent, come into close contact with one another, and their language and communicative behaviors in general take on features from a joint pool . . . . (Meeuwis and Östman 38)

(3) 量的な研究.「#902. 借用されやすい言語項目」 ([2011-10-16-1]) で示した "scale of adoptability" (or "borrowability scale") の仮説について,2言語使用者の話し言葉コーパスを用いて検証することができるようになってきた.Ottawa-Hull のフランス語における英語借用や,フランス語とオランダ語の2言語コーパスにおける借用の傾向,スペイン語とケチュア語の2限後コーパスにおける分析などが現われ始めている.

(4) 語用論における借用という新たなジャンルが切り開かれつつある.いまだ研究の数は少ないが,2言語使用者による談話標識 (discourse marker) や談話機能の借用の事例が報告されている.

(5) 上記の (3) と (4) とも関係するが,2言語使用者の借用に際する心理言語学的なアプローチも比較的新しい分野である.「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]) で覗いたように,code-switching との関連が問題となる.

(6) イントネーションやリズムなど韻律的要素の借用全般.

総じて最新の借用研究は,言語体系との関連において見るというよりは,話者個人あるいは社会との関連において見る方向へ推移してきているようだ.また,結果としての借用語 (loanword) に注目するというよりは,過程としての借用 (borrowing) に注目するという関心の変化もあるようだ.

私個人としては,従来型の言語体系との関連においての借用の研究にしても,まだ足りないところはあると考えている.例えば,意味借用 (semantic loan) などは,多く開拓の余地が残されていると思っている.

・ Treffers-Daller, Jeanine. "Borrowing." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 17--35.

・ Meeuwis, Michael and Jan-Ola Östman. "Contact Linguistics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 36--45.

2014-10-03 Fri

■ #1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間 [contact][loan_word][borrowing][sociolinguistics][language_change][causation][substratum_theory][code-switching][pidgin][creole][koine][koineisation]

「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]) と「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1]) でそれぞれ見たように,言語接触の類別の1つとして contact-induced language change がある.これはさらに借用 (borrowing) と接触による干渉 (shift-induced interference) に分けられる.前者は L2 の言語的特性が L1 へ移動する現象,後者は L1 の言語的特性が L2 へ移動する現象である.shift-induced interference は,第2言語習得,World Englishes,基層言語影響説 (substratum_theory) などに関係する言語接触の過程といえば想像しやすいかもしれない.

この2つは方向性が異なるので概念上区別することは容易だが,現実の言語接触の事例においていずれの方向かを断定するのが難しいケースが多々あることは知っておく必要がある.Meeuwis and Östman (41) より,箇条書きで記そう.

(1) code-switching では,どちらの言語からどちらの言語へ言語項が移動しているとみなせばよいのか判然としないことが多い.「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]) で論じたように,borrowing と shift-induced interference の二分法の間にはグレーゾーンが拡がっている.

(2) 混成語 (mixed language) においては,関与する両方の言語がおよそ同じ程度に与える側でもあり,受ける側でもある.典型的には「#1717. dual-source の混成語」 ([2014-01-08-1]) で紹介した Russenorsk や Michif などの pidgin や creole/creoloid が該当する.ただし,Thomason は,この種の言語接触を contact-induced language change という項目ではなく,extreme language mixture という項目のもとで扱っており,特殊なものとして区別している (cf. [2014-03-13-1]) .

(3) 互いに理解し合えるほどに類似した言語や変種が接触するときにも,言語項の移動の方向を断定することは難しい.ここで典型的に生じるのは,方言どうしの混成,すなわち koineization である.「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) と「#1690. pidgin とその関連語を巡る定義の問題」 ([2013-12-12-1]) を参照.

(4) "false friends" (Fr. "faux amis") の問題.L2 で学んだ特徴を,L1 にではなく,別に習得しようとしている言語 L3 に応用してしまうことがある.例えば,日本語母語話者が L2 としての英語の magazine (雑誌)を習得した後に,L3 としてのフランス語の magasin (商店)を「雑誌」の意味で覚えてしまうような例だ.これは第3の方向性というべきであり,従来の二分法では扱うことができない.

(5) そもそも,個人にとって何が L1 で何が L2 かが判然としないケースがある.バイリンガルの個人によっては,2つの言語がほぼ同等に第1言語であるとみなせる場合がある.関連して,「#1537. 「母語」にまつわる3つの問題」 ([2013-07-12-1]) も参照.

borrowing と shift-induced interference の二分法は,理論上の区分であること,そしてあくまでその限りにおいて有効であることを押えておきたい.

・ Meeuwis, Michael and Jan-Ola Östman. "Contact Linguistics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 36--45.

2014-09-15 Mon

■ #1967. 料理に関するフランス借用語 [loan_word][french][lexicology][norman_conquest][semantic_field][recipe]

昨日の記事「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1]) で,英語の料理や飲食物に関する語彙には,歴史的にフランス借用語が幅を利かせてきたことを確認した.その背景にあるのは,疑いなく1066年のノルマン・コンクェエストである.それ以降,「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]) で典型的に知られているように,アングロサクソン系の大多数の庶民は家畜の世話に追われ,フランス系の上流階級はフランスの料理に舌鼓を打った.イングランドにおいてフランス料理は,単においしいだけでなく,権威や洗練の象徴として社会的な含意をもっていた.

動物とその肉料理に関する sheep / mutton; ox / beef; pig / pork, bacon, gammon; calf / veal; boar / brawn; fowl / poultry の英仏語彙の対立はよく知られているが,ほかにもフランス借用語が料理に関する意味場を広く占めている証拠はたくさんある.昨日の記事で引用した Hughes は,"The sociology of food" (117--20) と題する節で,興味深い事例を列挙している.

まず,動物の可食部位で上質な部位と下等な部位とで呼び名が異なるという事実がある.haunch, joint, cutlet はフランス語だが,brains, tongue, shank は英語だ.ある程度豪華な食事を表わす dinner, supper, banquet はフランス語だが,質素な breakfast は英語だ(なお,lunch は16世紀末に初出し,昼食の意では19世紀から).火を通す調理法は「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) の COOK の配下に挙げた boil, broil, roast, grill, fry など多くの動詞がフランス語だ.スープ,デザート,調味料など風味の素材も然り (ex. soup, potage, sauce, dessert, mustard, cream, ginger, liquorice, flan, pasty, claret, biscuit) .アングロ・サクソンの食文化のひもじさが悲しいほどだ.

中世のご馳走を用意する係の名前にもフランス語が目立つ.steward (給仕長)こそ英語だが(sty + ward で「豚小屋世話人」というのが皮肉),marshal (接待係),sewer (配膳方),pantler (食料貯蔵室管理人),butler (執事)はフランス語である.下働きの scullion (皿洗い男),blackguard (召使い),pot-boy (ボーイ)はいずれも英語である.

最後に,15世紀のレシピの英文を覗いてみよう.Hughes (118) からの再引用だが,イタリック体の語がフランス借用語である.いかに料理の意味場がフランス語かぶれしているかが分かるだろう.

Oystres in grauey

Take almondes, and blanche hem, and grinde hem and drawe þorgh a streynour with wyne, and with goode fressh broth into gode mylke, and sette hit on þe fire and lete boyle; and cast therto Maces, clowes, Sugur, pouder of Ginger, and faire parboyled oynons mynced; And þen take faire oystres, and parboile hem togidre in faire water; And then caste hem ther-to, And let hem boyle togidre til þey ben ynowe; and serve hem forth for gode potage.

いかにもフランス語かぶれしている.しかし,かぶれていなかったら,今でさえ評価されることの少ないイングランドの食事情は,さらに貧しいものとなったに違いない.人たるもの,食の分野において purism の議論はあり得ない.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-14 Sun

■ #1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー [loan_word][french][history][lexicology]

Hughes (119) に,眺めているだけでおいしくなってくる英語の "A historical menu" が掲載されている.古英語期から現代英語期までに次々と英語へ入ってきた飲食物を表わす借用語が,時代順に並んでいる.Hughes は現代から古英語へと遡るように一覧を提示しており,昔の食べ物は素朴だったなあという感慨を得るにはよいのだが,下から読んだほうが圧倒的に食欲が増すので,そのように読むことをお勧めしたい.

| Food | Drink | |

|---|---|---|

| pesto, salsa, sushi | ||

| tacos, quiche, schwarma | ||

| pizza, osso bucco | Chardonnay | |

| 1900 | paella, tuna, goulash | |

| hamburger, mousse, borscht | Coca Cola | |

| grapefruit, éclair, chips | soda water | |

| bouillabaisse, mayonnaise | ||

| ravioli, crêpes, consommé | riesling | |

| 1800 | spaghetti, soufflé, bechamel | tequila |

| ice cream | ||

| kipper, chowder | ||

| sandwich, jam | seltzer | |

| meringue, hors d'oeuvre, welsh rabbit | whisky | |

| 1700 | avocado, pâté | gin |

| muffin | port | |

| vanilla, mincemeat, pasta | champagne | |

| salmagundi | brandy | |

| yoghurt, kedgeree | sherbet | |

| 1600 | omelette, litchi, tomato, curry, chocolate | tea, sherry |

| banana, macaroni, caviar, pilav | coffee | |

| anchovy, maize | ||

| potato, turkey | ||

| artichoke, scone | sillabub | |

| 1500 | marchpane (marzipan) | |

| whiting, offal, melon | ||

| pineapple, mushroom | ||

| salmon, partridge | ||

| Middle English | venison, pheasant | muscatel |

| crisp, cream, bacon | rhenish (rhine wine) | |

| biscuit, oyster | claret | |

| toast, pastry, jelly | ||

| ham, veal, mustard | ||

| beef, mutton, brawn | ||

| sauce, potage | ||

| broth, herring | ||

| meat, cheese | ale | |

| Old English | cucumber, mussel | beer |

| butter, fish | wine | |

| bread | water |

予想通りフランス借用語が多いものの,全体的にはバラエティ豊かで多国籍風である.

料理の分野におけるフランス語については,ほかにも「#61. porridge は愛情をこめて煮込むべし」 ([2009-06-28-1]),「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]),「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]),「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1]),「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1]),「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]),「#1792. 18--20世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2014-03-24-1]),「#1667. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (1)」 ([2013-11-19-1]),「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]) を参照.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-08 Mon

■ #1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造 [register][lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][greek][semantics][polysemy][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙に特徴的な三層構造について,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) などの記事でみてきた.三層構造という表現が喚起するのは,上下関係と階層のあるビルのような建物のイメージかもしれないが,ビルというよりは,裾野が広く頂点が狭いピラミッドのような形を想像するほうが妥当である.つまり,下から,裾野の広い低階層の本来語彙,やや狭まった中階層のフランス語彙,そして著しく狭い高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙というイメージだ.

ピラミッドの比喩が適切なのは,1つには,高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙のもつ特権的な地位と威信がよく示されているからだ.社会言語学的,文体的に他を圧倒するポジションについていることは,ビル型よりもピラミッド型のほうがよく表現できる.

2つ目として,それぞれの語彙の頻度が,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積として表現できるからである.昨日の記事「#1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合」 ([2014-09-07-1]) でみたように,話し言葉のみならず書き言葉においても,本来語彙の頻度は他を圧倒している(なお,この分布は,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) でみたように,現代日本語においても同様だった).対照的に,高階層の語彙は頻度が低い.個々の語については反例もあるだろうが,全体的な傾向としては,各階層の頻度と面積とは対応する.もっとも,各階層の語彙量(異なり語数)ということでいえば,必ずしもそれがピラミッドの面積に対応するわけでない.最頻100語(cf. 「#309. 現代英語の基本語彙100語の起源と割合」 ([2010-03-02-1]) と最頻600語(cf. 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1]))で見る限り,語彙量と面積はおよそ対応しているが,10000語というレベルで調査すると,「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1]) でみたように,上で前提としてきた3階層の上下関係は崩れる.

ピラミッドの比喩が有効と考えられる3つ目の理由は,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積が,頻度のみならず,構成語のもつ意味と用法の広さにも対応しているからだ.本来語は相対的に卑近であり頻度も高いが,そればかりでなく,多義であり,用法が多岐にわたる.基本的な語義が同じ「与える」でも,本来語 give は派生的な語義も多く極めて多義だが,ラテン借用語 donate は語義が限定されている.また,give は文型として SVOiOd も SVOd to Oi も取ることができる(すなわち dative shift が可能だ)が,donate は後者の文型しか許容しない.ほかには「#112. フランス・ラテン借用語と仮定法現在」 ([2009-08-17-1]) で示唆したように,語彙階層が統語的な振る舞いに関与していると疑われるケースがある.

この第3の観点から,Hughes (43) は,次のようなピラミッド構造を描いた.

![]()

上記の3点のほかにも,各階層の面積と語の理解しやすさ (comprehensibility) が関係しているという見方もある.結局のところ,語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にあるということだろう.ピラミッドの比喩は巧みである.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-08-24 Sun

■ #1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類 [typology][loan_word][latin][oe][christianity][borrowing][statistics]

「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]),「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]) に続いて,古英語のラテン借用語の話題.古英語におけるラテン借用語の数は,数え方にもよるが,数百個あるといわれる.諸研究を参照した Miller (53) は,その数を600--700個ほどと見積もっている.

Old English had some 600--700 loanwords from Latin, about 500 of which are common to Northwest Germanic . . ., and 287 of which are ultimately from Greek, seventy-nine via Christianity . . . .

個数とともに確定しがたいのはそれぞれの借用語の借用年代である.[2013-04-03-1]の記事では,Serjeantson に従って借用年代を (i) 大陸時代,(ii) c. 450--c. 650, (iii) c. 650--c. 1100 と3分して示した.これは多くの論者によって採用されている伝統的な時代別分類である.これとほぼ重なるが,第4の借用の波を加えた以下の4分類も提案されている.

(1) continental borrowings

(2) insular borrowings during the settlement phase [c. 450--600]

(3) borrowings [600+] from christianization

(4) learned borrowings that accompanied and followed the Benedictine Reform [c10e]

この4分類をさらに細かくした Dennis H. Green (Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge: CUP, 1998.) による区分もあり,Miller (54) が紹介している.それぞれの特徴について Miller より引用し,さらに簡単に注を付す.

(1a) an early continental phase, when the Angles and Saxons were in Schleswig-Holstein (contact with merchants) and on the North Sea littoral as far as the mouth of the Ems (direct contact with the Romans)

数は少なく,主として商業語が多い.ローマからの商品,器,道具など.wine が典型例.

(1b) a later continental period, when the Angles and Saxons had penetrated to the litus Saxonicum (Flanders and Normandy)

ライン川河口以西でローマ人との直接接触して借用されたと思われる street, tile が典型例.

(2a) an early phase, featuring possible borrowing via Celtic

この時期に属すると思われる例は,ガリアで話されていた俗ラテン語と音声的に一致しており,ブリテン島での借用かどうかは疑わしいともいわれる.

(2b) a later phase, with loans from the continental Franks as part of their influence across the Channel, especially on Kent

(3) begins "with the coming of Augustine and his 40 companions in 597, and possibly even at an earlier date, with the arrival of Bishop Liudhard in the retinue of Queen Bertha of Kent in the 560s"

この時期の借用語は古英語期以前の音韻変化をほとんど示さない点で,他の時期のものと異なっている.多くは教会ラテン借用語である.

(4) of a learned nature, culled from classical Latin texts, and differ little from the classical written form

実際には,ここまで細かく枠を設定しても,ある借用語をいずれの枠にはめるべきかを確信をもって決することは難しい.continental か insular かという大雑把な分類ですら難しく,さらに曖昧に early か later くらいが精一杯ということも少なくない.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-09 Sat

■ #1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図 [indo-european][family_tree][contact][loan_word][borrowing][geolinguistics][linguistic_area][historiography][french][latin][greek][old_norse]

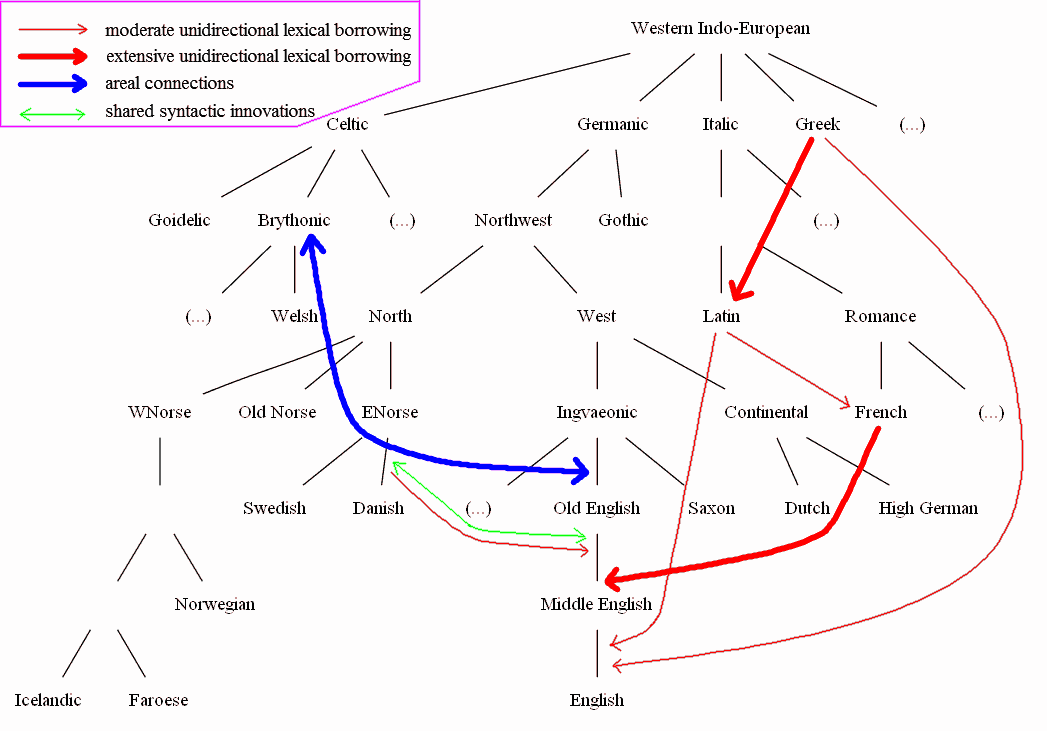

「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1925. 語派間の関係を示したインドヨーロッパ語族の系統図」 ([2014-08-04-1]) で触れてきたように,従来の言語系統図の弱点として,言語接触 (language contact) や地理的な隣接関係に基づく言語圏 (linguistic area; cf. 「#1314. 言語圏」 [2012-12-01-1])がうまく表現できないという問題があった.しかし,工夫次第で,系統図のなかに他言語からの影響に関する情報を盛り込むことは不可能ではない.Miller (3) がそのような試みを行っているので,見やすい形に作図したものを示そう.

この図では,英語が歴史的に経験してきた言語接触や地理言語学的な条件がうまく表現されている.特に,主要な言語との接触の性質,規模,時期がおよそわかるように描かれている.まず,ラテン語,フランス語,ギリシア語からの影響が程度の差はあれ一方的であり,語彙的なものに限られることが,赤線の矢印から見て取れる.古ノルド語 (ENorse) との言語接触についても同様に赤線の一方向の矢印が見られるが,緑線の双方向の矢印により,構造的な革新において共通項の少なくないことが示唆されている.ケルト語 (Brythonic) との関係については,近年議論が活発化してきているが,地域的な双方向性のコネクションが青線によって示されている.

もちろん,この図も英語と諸言語との影響の関係を完璧に示し得ているわけではない.例えば,矢印で図示されているのは主たる言語接触のみである(矢印の種類と数を増やして図を精緻化することはできる).また,フランス語との接触について,中英語以降の継続的な関与はうまく図示されていない.それでも,この図に相当量の情報が盛り込まれていることは確かであり,英語史の概観としても役に立つのではないか.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-06 Wed

■ #1927. 英製仏語 [waseieigo][french][loan_word]

和製英語について「#1492. 「ゴールデンウィーク」は和製英語か?」 ([2013-05-28-1]) や「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1]) で取り上げ,和製漢語について「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1]) で触れ,英製羅語について「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]) で言及してきた.関連して,今回は「英製仏語」の例を覗いてみよう.Jespersen (101--02) は,「英製仏語」に相当する呼称こそ使っていないが,まさにこの現象について議論している.

Fitzedward Hall in speaking about the recent word aggressive says, 'It is not at all certain whether the French agressif suggested aggressive, or was suggested by it. They may have appeared independently of each other'. The same remark applies to a great many other formations on a French or Latin basis; even if the several components of a word are Romanic, it by no means follows that the word was first used by a Frenchman. On the contrary, the greater facility and the greater boldness in forming new words and turns of expression which characterizes English generally in contradistinction to French, would in many cases speak in favour of the assumption that an innovation is due to an English mind. This I take to be true with regard to dalliance, which is so frequent in ME. (dalyaunce, etc.), while it has not been recorded in French at all. The wide chasm between the most typical English meaning of sensible (a sensible man, a sensible proposal) and those meanings which it shares with French sensible and Lat. sensibilis, probably shows that in the former meaning the word was an independent English formation. Duration as used by Chaucer may be a French word; it then went out of the language, and when it reappeared after the time of Shakespeare it may just as well have been reformed in England as borrowed; duratio does not seem to have existed in Latin. Intensitas is not a Latin word, and intensity is older than intensité.

この一節で Jespersen が「英製仏語」とみなしているものは,aggressive, dalliance, duration, intensity などである.対応する語がフランス語にあったとしても,英単語としてはおそらくイングランドで独立に発生したものだとみている.場合によっては,英製仏語がフランス語へ逆輸入された例もあっただろう.Jespersen は,上記の引用に続く節でも,mutinous, mutiny; cliquery; duty, duteous, dutiable などを英製仏語の候補として挙げている.この種の英製仏語は実際に調べ出せばいくつも出てくるのではないだろうか.

「○製△語」という現象を定義することの難しさについては「#1492. 「ゴールデンウィーク」は和製英語か?」 ([2013-05-28-1]) で見たとおりだが,そのような現象が生じる語史的な背景はおよそ指摘できる.「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1]) で論じたとおり,○言語が△言語からの語彙借用に十分になじんでくると,今度は△言語の語形成をモデルとして自家製の語彙を生み出そうとするのだ.より高次の借用段階に進むといえばよいだろうか.これは,英製仏語のみならず英製羅語,和製英語,和製漢語にも共通に見られる歴史的な過程である.「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]) や「#1878. 国訓,そして記号のリサイクル」 ([2014-06-18-1]) の記事の最後に述べた趣旨を改めて繰り返せば,「○製△語は,興味をそそるトピックとしてしばしば取り上げられるが,通言語的には決して特異な現象ではない」のである.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow