2020-10-09 Fri

■ #4183. 「記号のシニフィエ充填原理」 [semantics][semantic_change][bleaching][grammaticalisation][sign]

文法化 (grammaticalisation) の議論では,原義の強度が弱まる意味の漂白化 (bleaching) が話題になる.これ自体が意味変化 (semantic_change) の一種でもあるが,そのように意味が弱まって漂白化したスキをついて,その形式に対して新たな意味や機能が潜り込んでくるという点,つまり二次的な意味変化が続くという点がおもしろい.Meillet が意味変化の著名な論文 "Comment les mots changent de sens" (p. 7) で,この点に触れている.

En ce qui concerne spécialement le changement de sens, une circinstance importante est que le mot, soit prononcé, soit entendu, n'éveille presque jamais l'image de l'objet ou de l'acte dont il est le signe; comme l'a si justement dit M. Paulhan cité par M. Leroy, Le langage, p. 97: « comprendre un mot, une phrase, ce n'est pas avoir l'image des objets réels que représente ce mot ou cette phrase, mais bien sentir en soi un faible réveil des tendances de toute nature qu'éveillerait la perception des objets représentés par le mot ». Une image aussi peu évoquée, et aussi peu précisément, est par là même sujette à se modifier sans grande résistance.

ある記号 (sign) について,シニフィエが弱まると,スカスカになったその空隙を埋めるかのように,容易に別の意味や機能が入り込んでくるのだという.シニフィアンの立場からみると,常に確実で強固な相方(=シニフィエ)を欲するということになろうか.

この点と関連して想起されるのは,「#2212. 固有名詞はシニフィエなきシニフィアンである」 ([2015-05-18-1]) の最後に触れたことである.指示対象はもっているが,本来シニフィエをもたない固有名詞にすら,スカスカのシニフィエを埋めようとする作用が認められるということだ.これは「記号のシニフィエ充填原理」とでも呼びたくなる興味深い現象である.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "Comment les mots changent de sens." Année sociologique 9 (1906). 1921 ed. Rpt. Dodo P, 2009.

2020-04-12 Sun

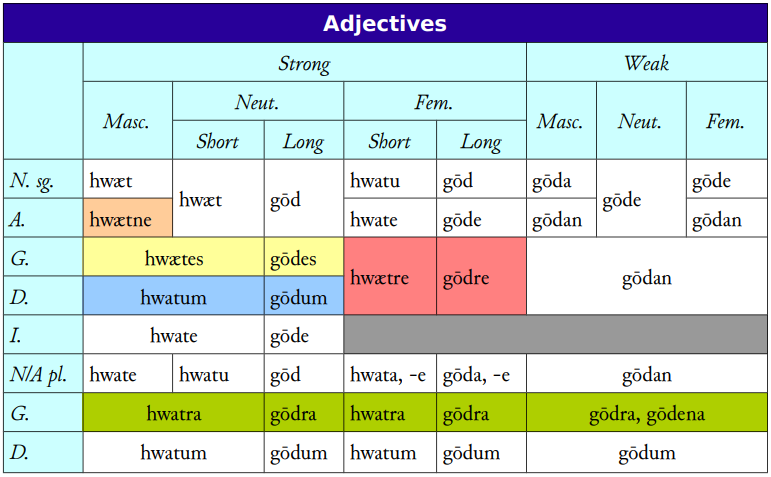

■ #4003. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化 (2) [adjective][inflection][oe][germanic][indo-european][comparative_linguistics][grammaticalisation][paradigm]

現代英語にはみられないが,印欧語族の多くの言語では形容詞 (adjective) に屈折 (inflection) がみられる.さらにゲルマン語派の諸言語においては,形容詞屈折に関して,統語意味論的な観点から強変化 (strong declension) と弱変化 (weak declension) の2種の区別がみられる(各々の条件については「#687. ゲルマン語派の形容詞の強変化と弱変化」 ([2011-03-15-1]) を参照).このような強弱の区別は,ゲルマン語派の著しい特徴の1つとされており,比較言語学的に興味深い(cf. 「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1])).

英語では,古英語期にはこの区別が明確にみられたが,中英語期にかけて屈折語尾の水平化が進行すると,同区別はその後期にかけて失われていった(cf. 「#688. 中英語の形容詞屈折体系の水平化」 ([2011-03-16-1]),「#2436. 形容詞複数屈折の -e が後期中英語まで残った理由」 ([2015-12-28-1]) ).現代英語は,形容詞の強弱屈折の区別はおろか,屈折そのものを失っており,その分だけゲルマン語的でも印欧語的でもなくなっているといえる.

古英語における形容詞の強変化と弱変化の屈折を,「#250. 古英語の屈折表のアンチョコ」 ([2010-01-02-1]) より抜き出しておこう.

では,なぜ古英語やその他のゲルマン諸語には形容詞の屈折に強弱の区別があるのだろうか.これは難しい問題だが,屈折形の違いに注目することにより,ある種の洞察を得ることができる.強変化屈折パターンを眺めてみると,名詞強変化屈折と指示代名詞屈折の両パターンが混在していることに気付く.これは,形容詞がもともと名詞の仲間として(強変化)名詞的な屈折を示していたところに,指示代名詞の屈折パターンが部分的に侵入してきたものと考えられる(もう少し詳しくは「#2560. 古英語の形容詞強変化屈折は名詞と代名詞の混合パラダイム」 ([2016-04-30-1]) を参照).

一方,弱変化の屈折パターンは,特徴的な n を含む点で弱変化名詞の屈折パターンにそっくりである.やはり形容詞と名詞は密接な関係にあったのだ.弱変化名詞の屈折に典型的にみられる n の起源は印欧祖語の *-en-/-on- にあるとされ,これはラテン語やギリシア語の渾名にしばしば現われる (ex. Cato(nis) "smart/shrewd (one)", Strabōn "squint-eyed (one)") .このような固有名に用いられることから,どうやら弱変化屈折は個別化の機能を果たしたようである.とすると,古英語の形容詞弱変化屈折を伴う se blinda mann "the blind man" という句は,もともと "the blind one, a man" ほどの同格的な句だったと考えられる.それがやがて文法化 (grammaticalisation) し,屈折という文法範疇に組み込まれていくことになったのだろう.

以上,Marsh (13--14) を参照して,なぜゲルマン語派の形容詞に強弱2種類の屈折があるのかに関する1つの説を紹介した.

・ Marsh, Jeannette K. "Periods: Pre-Old English." Chapter 1 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1--18.

2020-03-10 Tue

■ #3970. 言語学理論の2つの学派 --- 言語運用と言語能力のいずれを軸におくか [generative_grammar][cognitive_linguistics][grammaticalisation][construction_grammar][linguistics][language_change]

現代の言語学理論を大きく2つに分けるとすれば,言語運用 (linguistic performance) を重視する学派と言語能力 (linguistic competence) を重視する学派の2つとなろう.言語運用と言語能力の対立は,パロール (parole) とラング (langue) の対立といってもよいし,E-Language と I-Language の対立といってもよい.学派に応じて用語使いが異なるが,およそ似たようなものである.

言語運用を重視する学派は,文法化理論 (grammaticalisation theory) や構文文法 (construction_grammar) に代表される認知言語学 (cognitive_linguistics) である.一方,言語能力に重きをおく側の代表は生成文法 (generative_grammar) である.両学派の言語観は様々な側面で180度異なり,鋭く対立しているといってよい.Fischer et al. (32) の表を引用し,対立項を浮かび上がらせてみよう.

| EMPHASIS ON PERFORMANCE/LANGUAGE OUTPUT | EMPHASIS ON COMPETENCE/LANGUAGE SYSTEM | |

|---|---|---|

| (a) | product-oriented | process-oriented |

| (b) | emphasis on function (in CxG also form) | emphasis on form |

| (c) | locus of change: language use | locus of change: language acquisition |

| (d) | equality of levels | centrality (autonomy) of syntax |

| (e) | gradual change | radical change |

| (f) | heuristic tendencies | fixed principles |

| (g) | fuzzy categories/schemas | discrete categories/rules |

| (h) | contiguity with cognition | innateness of grammar |

言語変化 (language_change) に直接的に関わる側面 (c), (e) のみに注目しても,両学派の間に明確な対立があることがわかる.

印象的にいえば言語運用学派は動的,言語能力学派は静的ということになり,言語変化という動態を扱うには前者のほうが相性がよさそうにはみえる.

・ Fischer, Olga, Hendrik De Smet, and Wim van der Wurff. A Brief History of English Syntax. Cambridge: CUP, 2017.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2019-08-18 Sun

■ #3765.『英語教育』の連載第6回「なぜ一般動詞の疑問文・否定文には do が現われるのか」 [rensai][notice][word_order][syntax][syntax][do-periphrasis][grammaticalisation][interrogative][negative][auxiliary_verb][sociolinguistics][sobokunagimon]

8月14日に,『英語教育』(大修館書店)の9月号が発売されました.英語史連載「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ」の第6回となる今回の話題は,「なぜ一般動詞の疑問文・否定文には do が現われるのか」です.この do の使用は,英語統語論上の大いなる謎といってよいものですが,歴史的にみても,なぜこのような統語表現(do 迂言法と呼びます)が出現したのかについては様々な仮説があり,今なお熱い議論の対象になっています.

中英語期までは,疑問文や否定文を作る規則は単純でした.動詞の種類にかかわらず,疑問文では主語と動詞を倒置し,否定文では動詞のあとに否定辞を添えればよかったのです.現代英語の be 動詞や助動詞は,いまだにそのような統語規則を保ち続けていますので,中英語期までは一般動詞も同じ規則に従っていたと理解すればよいでしょう.しかし,16世紀以降,一般動詞の疑問文や否定文には,do 迂言法を用いるという新たな規則が発達し,確立していったのです.do の機能に注目すれば,do が「する,行なう」を意味する本動詞から,文法化 (grammaticalisation) という過程を経て助動詞へと発達した変化ともとらえられます.

記事ではなぜ do 迂言法が成立し拡大したのか,なぜ16世紀というタイミングだったのかなどの問題に触れましたが,よく分かっていないことも多いのが事実です.記事の最後では「もしエリザベス1世が結婚し継嗣を残していたならば」 do 迂言法はどのように発展していただろうかという,歴史の「もし」も想像してみました.どうぞご一読ください.

本ブログ内の関連する記事としては,「#486. 迂言的 do の発達」 ([2010-08-26-1]),「#491. Stuart 朝に衰退した肯定平叙文における迂言的 do」 ([2010-08-31-1]) を始めとして do-periphrasis の記事をご覧ください.

・ 堀田 隆一 「英語指導の引き出しを増やす 英語史のツボ 第6回 なぜ一般動詞の疑問文・否定文には do が現われるのか」『英語教育』2019年9月号,大修館書店,2019年8月14日.62--63頁.

2019-07-25 Thu

■ #3741. 中英語の不定詞マーカー forto [infinitive][preposition][grammaticalisation][pchron][caxton]

現代英語で不定詞マーカーといえば to である.別に原形不定詞というものもあるが,こちらはゼロのマーカーととらえられる.to 不定詞は原形不定詞と並んで古英語から用いられてはいたが,一気に拡大したのは後期古英語から初期中英語にかけての時期である (Mustanoja 514) .

中英語期までに to は完全に文法化 (grammaticalisation) を成し遂げ,形態・機能ともに弱化したこともあり,それを補強するかのように前置詞 for を前置した2音節の forto/for to が新たな不定詞マーカーとして用いられるようになった.MED の fortō adv. & particle (with infinitive) によると,初例は Peterborough Chronicle からであり,中英語の最初期から使用されていたことがわかる.

a1131 Peterb.Chron. (LdMisc 636) an.1127: Se kyng hit dide for to hauene sibbe of se earl of Angeow.

この新しい不定詞マーカー forto はかなりの頻度で用いらるようになったが,結局は to と同様に弱化の餌食となっていった.衰退の時期は14世紀から15世紀とみられ,Elizabeth 朝までにはほぼ廃用となった(非標準変種では現在も使われている).ただし,中英語期を通じて両者の揺れは観察され,Caxton の Morte Darthur では,時代錯誤的に forto のほうが優勢なくらいだった.

付け加えれば,中英語期には to や forto に比べてずっと稀ではあったが,単体の for,till, for till, at といった別の不定詞マーカーもあった (Mustanoja 515) .現代と異なり,不定詞の形は様々だったのである.

・ Mustanoja, T. F. A Middle English Syntax. Helsinki: Société Néophilologique, 1960.

2019-07-02 Tue

■ #3718. 英語に未来時制がないと考える理由 [future][tense][category][grammaticalisation][auxiliary_verb]

「#3692. 英語には過去時制と非過去時制の2つしかない!?」 ([2019-06-06-1]),「#3693. 言語における時制とは何か?」 ([2019-06-07-1]) で簡単に論じたように,英語における未来時制の存在は長らく議論の的になってきた.未来時制を認めるべきなのか,認めるとすればその根拠は何か.あるいは,認めるべきではないのか,そうだとすればその根拠は何か.『英語学要語辞典』の future tense の項 (269) で要約されている「英語に未来時制がない」とする説の根拠を示そう.

(1) 一般に「will/shall + 不定詞」という形式を「未来形」と称し,「未来時制」を表わすものと理解されているが,これはあくまで統語的な手段を利用しているにすぎないことに注意が必要である.一方,時制として確立されている「現在時制」と「過去時制」は,go と went のように動詞を屈折・変化させる形態的な手段により「現在形」と「過去形」を形成しており,will/shall go とはレベルが異なるように思われる.will/shall go が対立するのはむしろ would/should go であり,この対立自体が結局のところ「現在時制」対「過去時制」に還元されるというべきではないか.

(2) 上記のような手段の問題は別にしても,will/shall がどこまで文法化した形式的な語であるかという点についても疑義がある.各語は元来「意志」「負債,義務」を表わす本動詞であり,助動詞化したあとでもその原義はある程度残っている.他にも付随意味として「推量・習慣」「必然・強制」などの意味が残っており,純粋に「未来」の意味を担うものとはなっていない.一方 can, may, must, ought, be going to, be (about) to など他の(準)助動詞も,多かれ少なかれ「未来」の意味を担当しているため,もし will/shall を「未来」の助動詞と認めるのであれば,これらも同様に認めなければ一貫性が保てない.もっとも,法的な含意を伴わない純粋な「未来」を表わす用例が,will/shall に見られるというのも事実ではある.以下の事例を参照.

My babe-in-arms will be fifty-nine on my eighty-ninth birthday ... The year two thousand and fifteen when I shall be ninety. --- [F. R. Palmer]

英語に未来時制はあるのか,ないのかという問題は,一般に,所与の言語項がある文法範疇の成員であるとみなすためには,どのような条件が満たされていればよいのかという本質的な問いへとつながっていく.これは文法理論や言語観に関わるきわめて大きなトピックである.

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編)『英語学要語辞典』,研究社,2002年.298--99頁.

2018-12-24 Mon

■ #3528. 法助動詞を重ねられた時代 [auxiliary_verb][grammaticalisation][speed_of_change][syntax]

現代英語では,will, shall, can, may などの法助動詞を重ねて用いることはできない.法助動詞は1つのみで用いられ,その後に本動詞の原形が続くという形式しか許容されない.しかし,かつて法助動詞を2つ重ねることができた時代があった.

中尾 (350) を参照した縄田 (89--90) より,中英語からの例を示そう.

a. Shall 「未来」 + Will 「意志」

whase wilenn shall þiss boc efft oþerr sitþe written

'whoever shall wish to write this book afterwards another time' (?c1200 Orm D. 95)

b. Shall 「未来」 + Can 「能力」

I shal not konne answere.

'I shall not be able to answer.' (c1386 Chaucer, C. T. B 2902)

c. Shall 「未来」 + May 「能力」

Hu sal ani man ðe mugen deren?

'How shall any man be able to injure thee?' (c1250 Gen & Ex 1818)

d. May 「可能性」 + Can 「能力」

it may not kon worche þis work bot ȝif it be illuminid by grace

'it may not be able to do this work unless it be illumined by grace' (?a1400 Cloud 116, 14)

現在の法助動詞はもともとは一般動詞にすぎなかったが,歴史的に法助動詞へと文法化 (grammaticalisation) してきた経緯がある.しかし,一般動詞から法助動詞への範疇の移行は,一夜にして切り替えが生じたわけではなく,グラジュアルな過程だったために,その移行期においては上記のように両範疇の特性を合わせもったような「2つ重ね」が許容されたということだろう.しかし,近代英語以降,この構造は廃れていく.

縄田論文では,この2重法助動詞を巡る問題について,個々の助動詞間で法助動詞化の速度が異なっていたことが背景にあると議論されている.異なる立場からの関連する議論としては,「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]),「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1]) を参照.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『英語史 II』 英語学大系第9巻,大修館書店,1972年.

・ 縄田 裕幸 「第4章 分散形態論による文法化の分析 --- 法助動詞の発達を中心に ---」『文法化 --- 新たな展開 ---』秋元 実治・保坂 道雄(編) 英潮社,2005年.75--108頁.

2018-06-19 Tue

■ #3340. ゲルマン語における動詞の強弱変化と語頭アクセントの相互関係 [germanic][indo-european][stress][gradation][exaptation][aspect][tense][suffix][contact][stress][preterite][verb][conjugation][grammaticalisation][participle]

「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]) で6つの際立ったゲルマン語的な特徴を挙げた.Kastovsky (140) によると,そのうち以下の3つについては,ゲルマン祖語が発達する過程で互いに密接な関係があっただろうという.

(2) 動詞に現在と過去の2種類の時制がある

(3) 動詞に強変化 (strong conjugation) と弱変化 (weak conjugation) の2種類の活用がある

(4) 語幹の第1音節に強勢がおかれる

One major Germanic innovation was a shift from an aspectual to a tense system. This coincided with the shift to initial accent, and both may have been due to language contact, maybe with Finno-Ugric. Initial stress deprived ablaut of its phonological conditioning, and the shift from aspect to tense required a systematic marking of the new preterit tense. From this, two types of exponents emerged. One is connected to the secondary (weak) verbs, which only had present aspect/tense forms. They developed an affixal "dental preterit", together with an affix for the past participle. The source of the latter was the Indo-European participial -to-suffix; the source of the former is not clear . . . . The most popular theory is grammaticalization of a periphrastic construction with do (IE *dhe-), but there are a number of phonological problems with this. The second type was the functionalization of the originally non-functional ablaut alternations to express the new category, i.e. the making use of junk . . . . But this was somewhat unsystematic, because original perfect forms were mixed with aorist forms, resulting in a pattern with over- and under-differentiation. Thus, in class III (helpan : healp : hulpon : geholpen) the preterit is over-differentiated, because the different ablaut forms are non-functional, since the personal endings would be sufficient to signal the necessary distinctions. But in class I (wrītan : wrāt : writon : gewriten), there is under-differentiation, because some preterit forms and the past participle have the same vowel. (140)

Kastovsky によれば,ゲルマン祖語は,おそらく Finno-Ugric との言語接触の結果,(a) 印欧祖語的な相 (aspect) を重視する言語から時制 (tense) を重視する言語へと舵を切り,(b) 可変アクセントから固定的な語頭アクセントへと切り替わったという.新たに区別されるべきようになった過去時制の形態は,もともとは印欧祖語的なアクセント変異に依存していた母音変異 (gradation or ablaut) を(非機能的に)利用して作ったものと,歯音接尾辞 (dental suffix) を付すという新機軸に頼るものとがあった.これらの形態組織の複雑な組み替えにより,現代英語の動詞の非一環的な時制変化に連なる基盤が確立していったのである.一見すると互いに無関係に思われる現象が,音韻形態の機構において互いに関連していたという例の1つだろう.

上の引用で触れられている諸点と関連して,「#3135. -ed の起源」 ([2017-11-26-1]),「#2152. Lass による外適応」 ([2015-03-19-1]),「#2153. 外適応によるカテゴリーの組み替え」 ([2015-03-20-1]),「#3331. 印欧祖語からゲルマン祖語への動詞の文法範疇の再編成」 ([2018-06-10-1]) も参照.

・ Kastovsky, Dieter. "Linguistic Levels: Morphology." Chapter 9 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 129--47.

2018-04-21 Sat

■ #3281. Hopper and Traugott による文法化の定義と本質 [grammaticalisation][terminology][language_change]

Hopper and Traugott による文法化 (grammaticalisation) の定義および捉え方を紹介しておきたい.文法化というとき,それは言語変化のあるパターンを指すこともあれば,そのような言語変化を研究する枠組みのことを指すこともある.まずは,Hopper and Traugott (231) より,その辺りの定義から.

. . . we have considered grammaticalization as (i) a research framework for studying the relationships between lexical, constructional, and grammatical material in language, whether diachronically or synchronically, whether in particular languages or cross-linguistically, and (ii) a term referring to the change whereby lexical items and constructions come in certain linguistic contexts to serve grammatical functions and, once grammaticalized, continue to develop new grammatical functions.

(ii) の意味での文法化について,Hopper and Traugott (231) は,その本質は話し手と聞き手の間における意味の交渉であるとみている.文法化は,このようにコミュニケーションの基本的なポイントに立脚しているがゆえに,語用論的な観点や認知言語学的な観点も含み込むことになり,射程が広いフレームワークということになるのだろう.

We have argued that grammaticalization can be thought of as the result of the continual negotiation of meaning that speakers and hearers engage in in the context of discourse production and perception. The potential for grammaticalization lies in speakers attempting to be maximally informative, and in hearers attempting to be maximally cooperative, depending on the needs of the particular situation. Negotiating meaning may involve innovation, specifically, pragmatic, semantic, and ultimately grammatical enrichment. This means that grammaticalization is conceptualized as a type of change not limited to early child language acquisition or to perception (as is assumed in some models of language change), but due also to adult acquisition and to production.

この射程の広さが,文法化研究の魅力の1つといってよい.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-04-13 Fri

■ #3273. Lehman による文法化の尺度,6点 [grammaticalisation][category][tense][future][prototype]

通時的であれ共時的であれ文法化 (grammaticalisation) を問題にする場合,取りあげている事例がどの程度「文法化」らしいのか,「文法的」なのかを判断する基準が必要である.しかし,そのような基準を設定することは,言い換えれば文法化に定義を与えることにほかならず,自ずから困難な課題であることは論を俟たない.このような基準,ないしパラメータとしては,Lehmann の提案が古典的なものとされている.議論はあるものの,たたき台として重要である.Hopper and Traugott (31) に Lehmann のパラメータが要領よくまとまっているので,そちらを引用しよう.連合関係の軸 (paradigm) から3点,統合関係の軸 (syntagm) から3点である.

Of relevance on the paradigmatic axis are:

1. the "weight" or size of an element (Lehmann refers to "signs"); weight may be phonological (Lat. ille 'that' has more phonological weight than the French article le that derives from it) or semantic (the motion verb go is thought to be semantically weightier than the future marker go) --- "Grammaticalization rips off the lexical features until only the grammatical features are left" (1995: 129);

2. the degree to which an element enters into a cohesive set or paradigm; e.g., Latin tense is paradigmatically cohesive whereas English tense is not (contrast the Latin with its translation in amo 'I love,' amabo 'I will love,' amavi 'I have loved');

3. the freedom with which an element may be selected; in Swahili if a clause is transitive, an object marker must be obligatorily expressed in the verb (given certain semantic constraints), whereas none is required in English.

Of relevance on the syntagmatic axis are:

4. the scope or structural size of a construction; periphrasis, as in Lat. scribere habeo 'write:INF have:1stSg', is structurally longer and weightier and larger than inflection, as in Ital. scriverò, 'I shall write';

5. the degree of bonding between elements in a construction (there is a scale from clause to word to morpheme to affix boundary, 1995: 154); the degree of bonding is greater in the case of inflection than in that of periphrasis;

6. the degree to which elements of a construction may be moved around; in earlier Latin scribere habeo and habeo scribere could occur in either order, but in later Latin this order became fixed, which allowed the word boundaries to be erased.

これらを現代英語の文法事象に照らしてみよう.例えば,現代英語の法助動詞 will による「未来時制」の発達はどのくらい「文法化」的な問題だろうか.「#2317. 英語における未来時制の発達」 ([2015-08-31-1]),「#2208. 英語の動詞に未来形の屈折がないのはなぜか?」 ([2015-05-14-1]) で論じたように,法助動詞 will の発達は文法化の典型例の1つと考えられているが,上記の2から示唆される通り,現代英語の will による「未来時制」は連合関係の観点から,さほど cohesive とはいえないようにも思われ,どこまで時制という文法カテゴリーの成員として扱えるのか疑問が残る.もちろん,これは Yes/No の問題ではなく程度の問題であり,プロトタイプ的に理解する必要はあるだろう.6つのパラメータをすべて満たす完璧な事例だけを「文法化」としてしまうと,多くを見落としてしまうことになる.

・ Lehmann, Christian. Thoughts on Grammaticalization. Munich: Lincom Europa, 1995.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-04-12 Thu

■ #3272. 文法化の2つのメカニズム [metaphor][metonymy][analogy][reanalysis][syntax][grammaticalisation][language_change][auxiliary_verb][future][tense]

文法化 (grammaticalisation) の典型例として,未来を表わす助動詞 be going to の発達がある (cf. 「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1]),「#2106.「狭い」文法化と「広い」文法化」 ([2015-02-01-1]),「#2575. 言語変化の一方向性」 ([2016-05-15-1]) ) .この事例を用いて,文法化を含む統語意味論的な変化が,2つの軸に沿って,つまり2つのメカニズムによって発生し,進行することを示したのが,Hopper and Traugott (93) である.2つのメカニズムとは,syntagm, reanalysis, metonymy がタッグを組んで構成するメカニズムと,paradigm, analogy, metaphor からなるメカニズムである.以下の図を参照.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------- Syntagmatic axis

Mechanism: reanalysis

|

Stage I be going [to visit Bill] |

PROG Vdir [Purp. clause] |

|

Stage II [be going to] visit Bill |

TNS Vact |

(by syntactic reanalysis/metonymy) |

|

Stage III [be going to] like Bill |

TNS V |

(by analogy/metaphor) |

Paradigmatic axis

Mechanism: analogy

Stage I は文法化する前の状態で,be going はあくまで「行っている」という字義通りの意味をなし,それに目的用法の不定詞 to visit Bill が付加していると解釈される段階である.

Stage II にかけて,この表現が統合関係の軸 (syntagm) に沿って再分析 (reanalysis) される.隣接する語どうしの間での再分析なので,この過程にメトニミー (metonymy) の原理が働いていると考えられる.こうして,be going to は,今やこのまとまりによって未来という時制を標示する文法的要素と解釈されるに至る.

Stage II にかけては,それまで visit のような行為の意味特性をもった動詞群しか受け付けなかった be going to 構文が,その他の動詞群をも受け入れるように拡大・発展していく.言い換えれば,適用範囲が,動詞語彙という連合関係の軸 (paradigm) に沿った類推 (analogy) によって拡がっていく.この過程にメタファー (metaphor) が関与していることは理解しやすいだろう.文法化は,このように第1メカニズムにより開始され,第2メカニズムにより拡大しつつ進行するということがわかる.

文法化において2つのメカニズムが相補的に作用しているという上記の説明を,Hopper and Traugott (93) の記述により復習しておこう.

In summary, metonymic and metaphorical inferencing are comlementary, not mutually exclusive, processes at the pragmatic level that result from the dual mechanisms of reanalysis linked with the cognitive process of metonymy, and analogy linked with the cognitive process of metaphor. Being a widespread process, broad cross-domain metaphorical analogizing is one of the contexts within which grammaticalization operates, but many actual instances of grammaticalization show that conventionalizing of the conceptual metonymies that arise in the syntagmatic flow of speech is the prime motivation for reanalysis in the early stages.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-04-07 Sat

■ #3267. 談話標識とその形成経路 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][language_change][terminology][subjectification][intersubjectification][grammaticalisation][historical_pragmatics]

談話標識 (discourse marker, DM) について,「#2041. 談話標識,間投詞,挿入詞」 ([2014-11-28-1]) や discourse_marker の各記事で取り上げてきた.ここでは,種々の先行研究から要点をまとめた Archer に従って,談話標識の特徴と形成経路について紹介する.

まず,談話標識の特徴から.Archer (660) は次の4点を上げている.

- DMs are phonologically short items that normally occur sentence-initially (but can occur in medial or final position . . .);

- DMs are syntactically independent elements (often constituting separate intonation units) which occur with high frequency (in oral discourse in particular);

- DMs lack semantic content (i.e. they are non-referential/non-propositional in meaning)

- DMs are non-truth-conditional elements, and thus optional (i.e. they may be deleted).

たいていの談話標識は,歴史をたどれば,談話標識などではなかった.歴史の過程で,ある表現が談話標識らしくなってきたということである.では,どのような表現が談話標識へと発展しやすいのだろうか.典型的な談話標識の形成経路については,統語的な観点から記述したものと,意味論的な観点のものがある.まず,前者について (Archer 661) .

- adverb/preposition > conjunction > DM;

- predicate adverb > sentential adverb structure > parenthetical DM . . .;

- imperative matrix clause > indeterminate structure > parenthetical DM;

- relative/adverbial clause > parenthetical DM.

意味論的な観点からの経路は,次の通り (Archer 661) .

- truth-conditional > non-truth conditional . . .,

- content > procedural, and nonsubjective > subjective > intersubjective meaning,

- scope within the proposition > scope over the proposition > scope over discourse.

・ Archer, Dawn. "Early Modern English: Pragmatics and Discourse" Chapter 41 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 652--67.

2018-03-27 Tue

■ #3256. 偏流と文法化の一方向性 [grammaticalisation][drift][unidirectionality][language_change][inflection][synthesis_to_analysis][teleology]

言語の歴史における偏流 (drift) と,文法化 (grammaticalisation) が主張する言語変化の一方向性 (unidirectionality) は互いに関係の深い概念のように思われる.両者の関係について「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]),「#1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か?」 ([2014-09-19-1]) でも触れてきたが,今回は Hopper and Traugott の議論を通じてこの問題を考えてみたい.

Sapir が最初に偏流と呼んだとき,念頭にあったのは,英語における屈折の消失および迂言的表現の発達のことだった.いわゆる「総合から分析へ」という流れのことである (cf. synthesis_to_analysis) .後世の研究者は,これを類型論的な意味をもつ大規模な言語変化としてとらえた.つまり,ある言語の文法が全体としてたどる道筋としてである.

一方,文法化の文脈でしばしば用いられる一方向性とは,ある言語における全体的な変化について言われることはなく,特定の文法構造がたどるとされる道筋についての概念・用語であり,要するにもっと局所的な意味合いで使われるということだ.

Drift has to do with regularization of construction types within a language . . ., unidirectionality with changes affecting particular types of construction. (Hopper and Traugott 100)

偏流と一方向性は,全体的か局所的か,大規模か小規模か,構文タイプの規則化に関するものか個々の構文タイプの変化に関するものかという観点から,互いに異なるものとしてとらえるのがよさそうだ.「一方向性」という用語が用いられるときには,日常用語としてではなく,たいてい文法化という言語変化理論上の術語として用いられということを意識していないと,勘違いする可能性があるので要注意である.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-03-25 Sun

■ #3254. 高頻度がもたらす縮小効果と保存効果 [frequency][grammaticalisation][auxiliary_verb][suppletion][zipfs_law]

言語項目は,高頻度であればあるほど形態がすり減って縮小するということはよく知られている.一方,言語項目は高頻度であればあるほど,新たな形態に取って代わられることが少なく,古い形態を保持しやすいこともしられている.高頻度性がもたらすそれぞれの効果は,"Reduction Effect" (縮小効果),"Conservation Effect" (保存効果)と呼ばれている (Hopper and Traugott 127--28) .

縮小効果は,文法化 (grammaticalisation) と関連が深い.代表的な例は,「#64. 法助動詞の代用品が続々と」 ([2009-07-01-1]) で示したような新種の法助動詞群である.used to [ju:stə], have to [hæftə], have got to [hævgɑtə], (be) supposed to [spoʊstə], (be) going to [gɑnə] などの音形が,オリジナルの音形からすり減って縮小しているのが確認される.この効果は,「#1101. Zipf's law」 ([2012-05-02-1]) や「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1]) で取り上げた Zipf's law とも関係するだろう (cf. zipfs_law) .頻度と音形の長さには相関関係があるのだ(ただし,頻度と文法化の間には予想されるほどの関係はないと論じる,「#2176. 文法化・意味変化と頻度」 ([2015-04-12-1]) で紹介したような立場もあることを付け加えておこう).縮小効果の一般論としては,「#1091. 言語の余剰性,頻度,費用」 ([2012-04-22-1]) も参照されたい.

保存効果は,共時的には究極の不規則性を体現する形態,とりわけ補充法 (suppletion) の形態が,あちらこちらに残存していることから確認できる.人称代名詞の変化や be 動詞の活用など,超高頻度語においては古い形態がよく保持され,共時的にきわめて予測不可能な形態を示す.この点については,「#43. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか」 ([2009-06-10-1]),「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1]),「#2090. 補充法だらけの人称代名詞体系」 ([2015-01-16-1]),「#2600. 古英語の be 動詞の屈折」 ([2016-06-09-1]),「#694. 高頻度語と不規則複数」 ([2011-03-22-1]) を参照.もちろん保存効果は形態のみならず語順などの統語現象にも見られるので,言語について一般にいえることだろう.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2018-03-24 Sat

■ #3253. 語順の固定化は文法化の事例か否か [word_order][grammaticalisation]

Meillet が語順の固定化を文法化 (grammaticalisation) の事例とみなしたことは,「#1972. Meillet の文法化」([2014-09-20-1]) で触れた.通常,文法化とは語彙的な意味をもった具体的な語(句)が文法的な機能を帯びるようになる変化を指すが,抽象的な語順というものが文法化すると言う場合,それはいかなる点においてそうだと言えるのだろうか.Hopper and Traugott は,Meillet の1912年の記念すべき論文に言及しつつ,この点について解説している (23) .

At the end of the article he opens up the possibility that the domain of grammaticalization might be extended to the word order of sentences (1912: 147--8). In Latin, he notes, the role of word order was "expressive," not grammatical. (By "expressive," Meillet means something like "semantic" or "pragmatic.") The sentence 'Peter slays Paul' could be rendered Petrus Paulum caedit, Paulum Petrus caedit, caedit Paulum Petrus, and so on. In modern French and English, which lack case morphemes, word order has primarily a grammatical value. The change has marks of grammaticalization: (i) it involves change from expressive to grammatical meaning; (ii) it creates new grammatical tools for the language, rather than merely modifying already existent ones. The grammatical fixing of word order, then, is a phenomenon "of the same order" as the grammaticalization of individual words: "The expressive value of word order which we see in Latin was replaced by a grammatical value. The phenomenon is of the same order as the 'grammaticalization' of this or that word; instead of a single word, used with others in a group and taking on the character of a 'morpheme' by the effect of usage, we have rather a way of grouping words" (1912: 148).

引用中の (i) に示唆されているように,語用的・談話的な意味を担っていた語順の役割がより文法的になったと解釈できる点をとらえて,語順の固定化を文法化と呼んでいることがわかる.また,(ii) にあるように,当該言語が新たな「文法的な道具」を獲得したのだという主張も,なるほどと理解できる.

しかし,Hopper and Traugott は,語順の固定化が文法化と浅からぬ関係にあることは認めつつも,それ自体を文法化の事例とみなすのは妥当でないと考えている.その理由の1つは,語順の変化に必ずしも一方向性 (unidirectionality) が認められないことだ (60) .また,語順変化は他の文法化現象を引き起こす力をもっているという,語順変化の文法化に果たす間接的な役割についても,Hopper and Traugott は慎重な立場を取っている (61) .総じて,語順変化を文法化の話題として持ち出すのは控えておきたいというスタンスである.

・ Hopper, Paul J. and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. Grammaticalization. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "L'évolution des formes grammaticales." Scientia 12 (1912). Rpt. in Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1958. 130--48.

2018-02-18 Sun

■ #3219. 中英語に関する歴史語用論の話題 [me][pragmatics][historical_pragmatics][syntax][passive][grammaticalisation][invited_inference][implicature][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][standardisation]

古英語に関する歴史語用論の話題として,最近の2つの記事で触れた(cf. 「#3208. ポライトネスが稀薄だった古英語」 ([2018-02-07-1]),「#3211. 統語と談話構造」 ([2018-02-10-1])).およそ speech_act, politeness, discourse_analysis, information_structure に関する問題だった.今回は Traugott の概説にしたがって,中英語に関する歴史語用論の話題として,どのようなものがあるかを覗いてみたい.

Traugott は,ハンドブックの冒頭で3つを指摘している (466) .

(1) "the shift from information-structure-oriented word order in Old English to 'syntacticized' order in Middle English; this in tern led, at the end of the period, to new strategies for marking topic and focus in special ways."

(2) "the development of auxiliary verbs in contexts where implied abstract temporal, modal, or aspectual meanings of certain concrete verbs became salient"

(3) "the appearance of a large set of new discourse types, from romances to drama, scientific writings, and letters"

(1) は語用論と統語論のインターフェースに関わる精緻な問題といってよい.古英語から中英語にかけて屈折が衰退し,語順が固定化していったことにより,以前は比較的自由な語順を利用して情報構造を整えるという方略をもっていたものが,今や語順に頼ることができなくなったために,別の手段に訴えかけなければならなくなったということである.例えば,後期中英語に,行為者を標示する by 句を伴う受動態の構文が発達してきたことは,このような情報構造上の要請に起因する部分があるかもしれない.もしこの仮説が受け入れられるのであれば,語用論的な要因こそがくだんの統語変化の引き金となったと言えることになろう.

(2) も統語的な含みをもち,(1) と間接的に関連すると思われるが,主に本動詞から助動詞への発達(いわゆる典型的な文法化 (grammaticalisation) の事例)を説明するのに,文脈に助けられた含意 (implicature) や誘導推論 (invited_inference) などの道具立てをもってする研究を指す.中英語期には屈折の衰退による接続法・仮定法の衰退により,統語的な代替手段として法助動詞が発達するが,この発達にも語用論的なメカニズムが関与している可能性がある.

(3) は新種の談話の出現である.時代が下るにつれ,以前の時代にはなかったジャンルやテキスト・タイプが現われてくることは中英語期に限った現象ではないが,中英語でも確かに新種が生み出された.Traugott はロマンス,演劇,科学的文章,手紙といったジャンルを指摘しているが,その他にもフランス語(およびラテン語)の影響を受けた,あるいは混合した多言語使用の散文や韻文なども挙げられるだろう.

ほかに中英語後期には英語の書き言葉の標準化 (standardisation) も起こり始めており,誰がいつどこで標準変種を用いたのか,用いなかったのかといった社会語用論的な問題も議論の対象となるだろう.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "Middle English: Pragmatics and Discourse" Chapter 30 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 466--80.

2017-11-26 Sun

■ #3135. -ed の起源 [suffix][preterite][participle][germanic][indo-european][verb][inflection][etymology][reduplication][gothic][grammaticalisation][preterite-present_verb][degemination][sobokunagimon]

現代英語における動詞の過去(分詞)形を作る接尾辞 -ed は "dental suffix" とも呼ばれ,その付加はゲルマン語に特有の形態過程である(「#182. ゲルマン語派の特徴」 ([2009-10-26-1]) を参照).これによってゲルマン諸語は,語幹母音を変化させて過去時制を作る印欧語型の強変化動詞(不規則変化動詞)と,件の dental suffix を付加する弱変化動詞(規則変化動詞)とに2分されることになった.後者は「規則的」なために後に多くの動詞へ広がっていき,現代英語の動詞形態論にも大きな影響を及ぼしてきた(「#178. 動詞の規則活用化の略歴」 ([2009-10-22-1]),「#764. 現代英語動詞活用の3つの分類法」 ([2011-05-31-1]) を参照).

現代英語の -ed のゲルマン語における起源については諸説あり,決着がついていない.しかし,ある有力な説によると,この接尾辞は動詞 do と同根ではないかという.しかし,do 自体が補助動詞的な役割を果たすということは認めるにせよ,過去(分詞)の意味がどこから出てくるのかは自明ではない.同説によると,ゲルマン語において do に相当する語幹が,過去時制を作るのに重複 (reduplication) という古い形態過程をもってしたために,同じ子音が2度現われる *dēd- などの形態となった.やがて中間母音が消失して問題の子音が合わさって重子音となったが,後に脱重子音化して,結局のところ *d- に収まった.つまり,-ed の子音は,do の語幹子音に対応すると同時に,それが過去時制のために重複した同子音にも対応することになる.

では,この説は何らかの文献上の例により支持されるのだろうか.ゴート語に上記の形態過程をうかがわせる例が見つかるという.Lass (164) の説明を引こう.

The origin of the weak preterite is a perennial source of controversy. The main problem is that it is a uniquely Germanic invention, which is difficult to connect firmly with any single IE antecedent. Observing the old dictum ex nihilo nihil fit (nothing is made out of nothing), scholars have proposed numerous sources, none of which is without its difficulties. The main problem is that there are at least three consonantisms: /d/ (Go nasida 'I saved', inf. nasjan), /t/ (Go baúhta 'I bought', inf. bugjan), and /s/ (Go wissa 'I knew', inf *witan).

But even given this complexity, the most likely primary source seems to be compounding of an original verbal noun of some sort with the verb */dhe:-/ 'put, place, do' (OHG tuon, OE dōn, OCS dějati 'do', Skr dádhati 'he places', L fēci 'I made, did').

This leads to a useful analysis of a Gothic pret 3 ppl like nasidēdun 'they saved':

(7.18) nas - i -dē - d - un

SAVE-theme-reduplication-DO-3 pl

I.e. a verbal root followed by a thematic connective followed by the reduplicated perfect plural of 'do'. This gives a periphrastic construction with a sense like 'did V-ing'; with, significantly, Object-Verb order . . ., i.e. (7.18) has the form of an OV clause 'NP-pl sav(ing) did'. An extended form also existed, in which a nominalizing suffix */-ti/ or */-tu/ was intercalated between the root and the 'do' form, e.g. in Go faúrhtidēdun 'they feared', which can be analysed as {faúrh-ti-dē-d-un}. This suffix was in many cases later weakened; first the vowel dropped, so that */-ti-d-/ > */-td-/; this led to assimilation */-tt-/, and then eventual reinterpretation of the /t/-initial portion as a suffix itself, and loss of the 'do' part from verbs of this type . . . . The problematic /s(s)/ forms may go back to a different (earlier) development also involving */-ti/, in which the sequence */tt/ > /s(s)/ . . . but this is not clear.

要するに,-ed 付加の原型は次の通りだ.まず動詞語幹に名詞化する形態操作を施し,いわば動名詞のようなものを作る.その直後に,do の過去形 did のようなものを置いて,全体として「(動詞)の動作を行なった」とする.このようにもともとはOV型の迂言的な統語構造として始まったが,やがて全体がつづまって複合語のようなものとしてとらえられるようになり,形態的な過程へと移行した.この段階に至って,-ed に相当する部分は,語彙的な要素というよりは接尾辞,すなわち拘束形態素と解釈された.一種の文法化 (grammaticalisation) の例とみてよいだろう.

上の引用で Lass は Go wissa に言及するとともに,最後に /s(s)/ を巡る問題に言い及んでいるが,対応する古英語にも過去現在動詞 wāt の過去形として wiste/wisse があり,音韻形態的に難しい課題を投げかけている.これについては,「#2231. 過去現在動詞の過去形に現われる -st-」 ([2015-06-06-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Lass, Roger. Old English: A Historical Linguistic Companion. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2017-08-13 Sun

■ #3030. on foot から afoot への文法化と重層化 [grammaticalisation][clitic]

表記の話題は,「#2723. 前置詞 on における n の脱落」 ([2016-10-10-1]) と「#2948. 連載第5回「alive の歴史言語学」」 ([2017-05-23-1]),および連載記事「alive の歴史言語学」で取り上げてきたが,これを文法化 (grammaticalisation) の1例としてとらえる視点があることを紹介したい.

Los (43) によれば,on foot から afoot への変化は,韻律,音韻,形態,統語,語彙のすべての側面において,文法化に典型的にみられる特徴を示す.

| on foot > afoot | |

| Prosody | stress is reduced |

| Phonology | [on] > [ə]: final -n is lost, vowel is reduced |

| Morphology | on is a free word, a- a bound morpheme |

| Syntax | on foot is a phrase (a PP), afoot is a head (an adverb) |

| Lexicon | on has a concrete spatial meaning, a- has a very abstract, almost aspectual meaning ('in progress'); afoot no longer refers to people being on their feet, i.e. active, but to things being in operation: the game is afoot |

文法化において興味深いことは,on foot が afoot へ文法化したと言えるとしても,on foot も消えずに残っていることだ.つまり,前置詞句 on foot が副詞 afoot に置換されたわけではなく,前置詞句から副詞が派生して独立したというべきであり,結果として両表現が役割を違えて共存しているのである.同じことは,表現全体についてだけではなく,小さい単位についてもいえる.前置詞 on は接語 (clitic) a- に置換されたわけではなく,前置詞から接語が派生して独立したということだ.前置詞 on 自体は無傷で残っている.

文法化の後で,もともとの表現と新しい表現が機能を違えて共存している状況は,文法化における重層化 (layering) の現象として知られている.ほかの例を挙げれば,「#2490. 完了構文「have + 過去分詞」の起源と発達」 ([2016-02-20-1]) で紹介したように,完了形を作る助動詞としての have は,同形の動詞が文法化したものだが,結果として動詞と助動詞が2つの層をなして共存している.すべての文法化の事例が後に安定的な重層化をもたらすわけではなく,古い形式・機能が廃れてしまうケースも多々あることは確かだが,文法化を論じる上で重層化という現象には注意しておきたい.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-08-11 Fri

■ #3028. She is believed to have done it. の構文と古英語モーダル sceolde の関係 [syntax][auxiliary_verb][passive][ecm][passive][information_structure][grammaticalisation]

I believe that she has done it. という文は that 節を用いずに I believe her to have done it. とパラフレーズすることができる.前者の文で「それをなした」主体は she であり,当然ながら主格の形を取っているが,後者の文では動作の主体は同じ人物を指しながら her と目的格の形を取っている.これは,不定詞の意味上の主語ではあり続けるものの,統語上1段上にある believe の支配下に入るがゆえに,主格ではなく目的格が付与されるのだと説明される.統語論では,後者のような格付与のことを Exceptional Case-Marking (= ECM) と呼んでいる.また,believe の取るこのような構文は,対格付き不定詞の構文とも称される.

上の believe の例にみられるようなパラフレーズは,think や declare に代表される「思考」や「宣言」を表わす動詞で多く可能だが,興味深いのは,ECM 構文は受動態で用いられるのが普通だということである.上記の例はあえて能動態の文を取り上げたが,She is believed to have done it. のように受動態で現われることのほうが圧倒的に多い.実際 say などでは,能動態での ECM 構文は許容されず,The disease is said to be spreading. のようにもっぱら受動態で現われる.

この受動態への偏りは,なぜなのだろうか.

1つには,「思考」や「宣言」において重要なのは,その内容の主題である.上の例文でいえば,she や the disease が主題であり,それが文頭で主語として現われるというのは,情報構造上も自然で素直である.

もう1つの興味深い観察は,is believed to なり is said to の部分が,全体として evidentiality を表わすモーダルな機能を帯びているというものだ.つまり,reportedly ほどの副詞に置き換えることができそうな機能であり,古い英語でいえば sceolde "should" という法助動詞で表わされていた機能である.Los (151) によれば,

Another interesting aspect of passive ECMs is that they renew a modal meaning of sceolde 'should' that had been lost. Old English sceolde could be used to indicate 'that the reporter does not believe the statement or does not vouch for its truth' . . . :

Þa wæs ðær eac swiðe egeslic geatweard, ðæs nama sceolde bion Caron <Bo 35.102.16>

'Then there was also a very terrible doorkeeper whose name is said to be Caron'

The most felicitous PDE translation has a passive ECM.

ある意味では,be believed to や be said to が,be going to などと同じように法助動詞へと文法化 (grammaticalisation) している例とみることもできるだろう.

・ Los, Bettelou. A Historical Syntax of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

2017-04-28 Fri

■ #2923. 左と右の周辺部 [pragmatics][grammaticalisation][syntax][subjectification][intersubjectification][implicature]

近年,語用論では,「周辺部」 (periphery) 周辺の研究が注目されてきている.先月も青山学院大学の研究プロジェクトをベースとした周辺部に関する小野寺(編)の論考集『発話のはじめと終わり』が出版された(ご献本ありがとうございます).

理論的導入となる第1章に「周辺部」の定義や研究史についての解説がある.作業上の定義を確認しておこう (9) .

周辺部とは談話ユニットの最初あるいは最後の位置であり,そこではメタテクスト的ならびに/ないしはメタ語用論的構文が好まれ,ユニット全体を作用域とする

周辺部には最初の位置(すなわち左)と最後の位置(右)の2つがあることになるが,両者の間には働きの違いがあるのではないかと考えられている.先行研究によれば,「左と右の周辺部の言語形式の使用」として,次のような役割分担が仮説され得るという (25) .

| 左の周辺部 (LP) | 右の周辺部 (RP) |

|---|---|

| 対話的 (dialogual) | 二者の視点的 (dialogic) |

| 話順を取る/注意を引く (turn-taking/attention-getting) | 話順を(譲り,次の話順を)生み出す/終結を標示する (turn-yielding/end-marking) |

| 前の談話につなげる (link to previous discourse) | 後続の談話を予測する (anticipation of forthcoming discourse) |

| 返答を標示する (response-marking) | 返答を促す (response-inviting) |

| 焦点化・話題化・フレーム化 (focalizing/topicalizing/framing) | モーダル化 (modalizing) |

| 主観的 (subjective) | 間主観的 (intersubjective) |

周辺部の問題は,語用論と統語論の接点をなすばかりでなく,文法化 (grammaticalisation),主観化 (subjectification),間主観化 (intersubjectification),慣習的含意 (conventional implicature) の形成など広く言語変化の事象にも関与する.今後の展開が楽しみな領域である.

・ 小野寺 典子(編) 『発話のはじめと終わり ―― 語用論的調整のなされる場所』 ひつじ書房,2017年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow