2015-03-29 Sun

■ #2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移 [oed][loan_word][statistics][french][latin][lexicology]

Wordorigins.org の "Where Do English Words Come From?" と題する記事では,OED をソースとした語種比率の通時的推移の調査報告がある.古英語から現代英語への各世紀に,語源別にどれだけの新語が語彙に加えられたかが解説とともにグラフで示されている.本文中にも述べられているように,見出し語の語源に関して OED の語源欄より引き出された情報は,眉に唾をつけて解釈しなければならない.というのは,語源欄にある言語が言及されていたとしても,それが借用元の語源を表すとは限らないからだ.しかし,およその参考になることは確かであり,通時的な概観のために有用であることには相違ない.

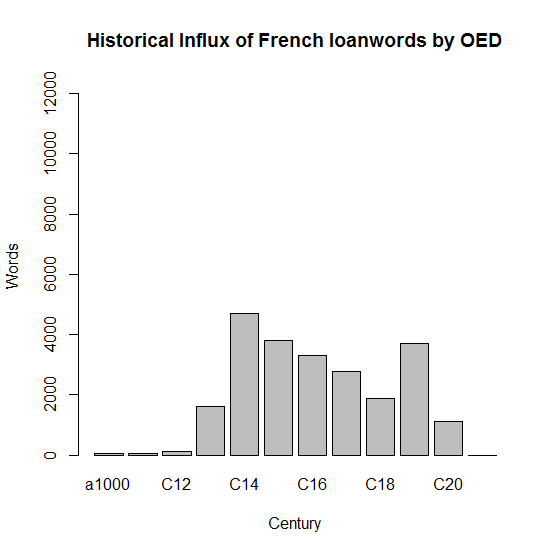

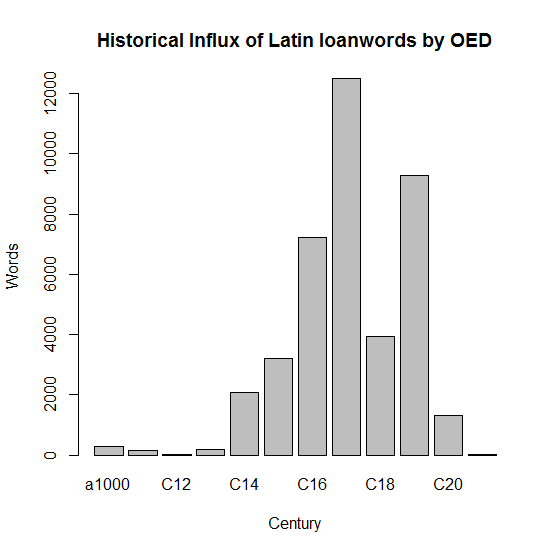

ここでは,CSV形式あるいはEXCEL形式で公開されている世紀別で語源別の数値を拝借し,フランス語とラテン語から英語語彙へ追加された借用語の推移をグラフ化して並べてみた.

|

|

得られた傾向は,一般的な概説書で述べられているものと一致する.フランス語のピークは後期中英語,ラテン語のピークは初期近代英語である.比較すると,ラテン語の規模の著しさがよくわかる.フランス語とラテン語からの借用語に関連する統計については,すでに以下のように多くの記事で取り上げてきたので,そちらも参照されたい.

[2009-08-22-1]: #117. フランス借用語の年代別分布

[2009-11-15-1]: #202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合

[2010-06-30-1]: #429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合

[2010-12-12-1]: #594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴

[2011-02-16-1]: #660. 中英語のフランス借用語の形容詞比率

[2011-08-20-1]: #845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合

[2011-09-18-1]: #874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布

[2012-08-11-1]: #1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)

[2012-08-18-1]: #1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分

[2012-08-20-1]: #1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧

[2012-09-03-1]: #1225. フランス借用語の分布の特異性

[2012-09-04-1]: #1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布

[2012-11-12-1]: #1295. フランス語とラテン語の2重語

[2014-08-24-1]: #1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類

また,OED の利用に際しては,以下の記事も参照されたい.

[2010-10-10-1] #:531. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか

[2010-10-14-1] #:535. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (2)

[2010-10-15-1] #:536. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (3)

[2011-01-05-1] #:618. OED の検索結果から語彙を初出世紀ごとに分類する CGI

[2011-01-29-1] #:642. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (4)

2015-03-24 Tue

■ #2157. word pair の種類と効果 [binomial][french][loan_word][chaucer][ancrene_wisse][bible]

binomial (2項イディオム)と呼ばれる "A and B" などの型の表現について,binomial の記事で扱ってきた.binomials は,word pair, paired word, doublets, collocated words などとも呼ばれる."A and B" 型に限らず広く定義すると「接続詞により結合された,同一の統語位置を占める2語」(片見,p. 170)となる(以下では呼称を word pair に統一).英語史における word pair の研究は盛んだが,それはとりもなおさず古い英語では word pair が著しく豊かだったからである.特に近代英語期の始まりまでは,ごく普通に見られた.

word pair にもいろいろな型があるが,語源的にみれば本来語か(主としてフランス語からの)借用語かという組み合わせによって英英タイプ,(順不同で)英仏タイプ,仏仏タイプに分けられる.一方,word pair の効果にもいくつかの種類が区別される.「#820. 英仏同義語の並列」 ([2011-07-26-1]) でも述べたが,文体的・修辞的な狙いもあれば,馴染みのない片方の語の理解を促すために,馴染みの深いもう片方の語を添えるという狙いもある.あるいは,「#1443. 法律英語における同義語の並列」 ([2013-04-09-1]) でみたように,特に英仏タイプの法律用語において,あえていずれか一方を選択するという労をとらなかっただけということもあるかもしれない.また,いずれの場合にも,意味を強調するという働きはある程度は含まれているのではないか.

各要素の語源に注目した分類と効果に注目した分類が,いかなる関係にあるのかという問題は興味深いが,とりわけ英仏タイプに関して,フランス借用語の意味を理解させるために本来語を添えたとおぼしき例が多いことは想像に難くない.Jespersen (89--90) は,Ancrene Riwle からの例として次のような word pair を挙げている.

cherité þet is luve

in desperaunce, þet is in unhope & in unbileave forte beon iboruwen

Understondeð þet two manere temptaciuns---two kunne vondunges---beoð

pacience, þet is þolemodnesse

lecherie, þet is golnesse

ignoraunce, þet is unwisdom & unwitenesse

一方,Chaucer は英仏タイプを文体的・修辞的に,あるいは強調の目的で使用することが多かったとされる.Jespersen (90) はこのことを以下のように例証している.

In Chaucer we find similar double expressions, but they are now introduced for a totally different purpose; the reader is evidently supposed to be equally familiar with both, and the writer uses them to heighten or strengthen the effect of the style; for instance: He coude songes make and wel endyte (A 95) = Therto he coude endyte and make a thing (A 325) | faire and fetisly (A 124 and 273) | swinken with his handes and laboure (A 186) | Of studie took he most cure and most hede (A 303) | Poynaunt and sharp (A 352) | At sessiouns ther was he lord and sire (A 355).

谷を参照した片見 (174--75) によれば,Chaucer が散文中に用いた word pairs 全体のうち73%までが英仏タイプか仏仏タイプであるとされ,Chaucer が聴衆や読者に求めたフランス語の水準の高さが想像される.

使用した word pair の種類に関して Chaucer の対極に近いところにあるものとして,片見 (174--75) は,英英タイプの比率が相対的に高い欽定訳聖書や神秘主義散文を挙げている.これらのテキストでは,英英タイプが word pairs 全体の半数近く,あるいはそれ以上を占めているという.だが,その狙いは Chaucer と異ならず,文体的・修辞的なもののようである.というのは,英英タイプを多用することで,「荒削りではあるが力強い文体」(片見,p. 175)を作り出すことに貢献しているからだ.word pair の種類と効果を考える上では,個々の作家やテキストの特性を考慮に入れる必要があるということだろう.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

・ 片見 彰夫 「中世イングランド神秘主義者の散文における説得の技法」『歴史語用論の世界 文法化・待遇表現・発話行為』(金水 敏・高田 博行・椎名 美智(編)),ひつじ書房,2014年.163--88頁.

・ 谷 明信 「Chaucer の散文作品におけるワードペア使用」『ことばの響き――英語フィロロジーと言語学』(今井 光規・西村 秀夫(編)),開文社,2008年.89--116頁.

2015-03-15 Sun

■ #2148. 中英語期の diglossia 描写と bilingualism 擁護 [bilingualism][french][diglossia][popular_passage]

中英語社会が英語とフランス語による diglossia を実践していたことは,「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) や「#1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化」 ([2012-08-12-1]) などの記事で見てきたとおりである.しかし,その2言語使用状態に直接言及するような記述を探すのは必ずしもたやすくない.ましてや,その2言語状況について評価を下すようなコメントは見つけにくい.だが,そのなかでもこれらの事情に言及した有名な一節がある.Robert of Gloucester (fl. 1260--1300) の Chronicle からの一節で,以下,Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse 所収の The metrical chronicle of Robert of Gloucester より該当箇所を引用しよう.

& þe normans ne couþe speke þo / bote hor owe speche (l. 7538)

& speke french as hii dude atom / & hor children dude also teche

So þat heiemen of þis lond / þat of hor blod come (l. 7540)

Holdeþ alle þulke speche / þat hii of hom nome

Vor bote a man conne frenss / me telþ of him lute

Ac lowe men holdeþ to engliss / & to hor owe speche ȝute

Ich wene þer ne beþ in al þe world / contreyes none

Þat ne holdeþ to hor owe speche / bote engelond one (l. 7545)

Ac wel me wot uor to conne / boþe wel it is

Vor þe more þat a mon can / þe more wurþe he is

ノルマン人はイングランドにやってきたときにはフランス語のみを用いており,その子孫たる "heiemen" もフランス語を保持していたこと,その一方で "lowe men" は英語のみを用いていたことが述べられている.これはまさに diglossia における H (= High variety) と L (= Low variety) の区別への直接の言及である.また,フランス語を知らないと社会的に低く見られるというコメントも挿入されている.さらに,引用の終わりのほうでは,両言語を知っているほうがよい,そのほうが社会的に価値が高いとみなされると,英仏語の bilingualism を擁護するコメントも付されている.

実際のところ,Chronicle が書かれた13世紀末には,貴族の師弟でもあえて学習しなければフランス語をろくに使いこなせないという状態になっていた.貴族の師弟のフランス語力の衰えは,「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) でみたように,13世紀までにはすでに顕著になっていたようだ.しかし,フランス語の社会言語学的地位は依然として高かったため,余計にフランス語学習が奨励されたということにもなった.このような状況において Robert of Gloucester は,両言語を操れることの大切さを説いたのである.

2015-03-14 Sat

■ #2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判 [purism][loan_word][french][inkhorn_term][me][lexicology]

16世紀には,ラテン借用語をはじめとしてロマンス諸語などからの借用語がおびただしく英語へ流入した(「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) や「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照).日本語でも明治以降,大量の漢語が作られ,昭和以降は無数のカタカナ語が流入した(「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1]) 及び「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]) を参照).これらの時代の各々において,純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの借用語批判が聞かれた.借用語をむやみやたらに使用するのは控えて,本来語をもっと多く使うべし,という議論である.

英語史においてあまり聞かないのは,中英語期に怒濤のように押し寄せたフランス借用語に対する批判である.「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たとおり,英語はノルマン・コンクェスト後の数世紀間で,歴史上初めて数千語という規模での大量語彙借用を経験してきたが,そのフランス借用語への批判はなかったのだろうか.

確かにルネサンス期のインク壺語批判ほどは目立たないが,中英語におけるフランス借用語批判がまったくなかったわけではない.Ranulph Higden (c. 1280--1364) によるラテン語の Polychronicon を1387年に英訳した John of Trevisa (1326--1402) は,ある一節で,古ノルド語とともにフランス語からの借用語の無分別な使用について苦情を呈している.Crystal (186) からの引用を再現しよう.

by commyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys apeyred, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbittyng.

同様に,Richard Rolle of Hampole (1290?--1349.) による Psalter (a1350) でも,"seke no strange Inglis" (見知らぬ英語は使わない)とフランス借用語に対して暗に不快感を示しているし,15世紀に Polychronicon を英訳した Osbern Bokenham (1393?--1447?) も,フランス語が英語を野蛮にしたと非難している (Crystal 186) .しかし,彼らとて,自らの著書のなかで,洗練されたフランス借用語を用いていたことはいうまでもない.

このように中英語期のフランス借用語への純粋主義的な非難はいくつか確認されるが,後世の激しいインク壺語批判に比べれば単発的であり,特に大きな潮流を形成しなかったようだ.英語自体がまだ一国の言語としておぼつかない地位にあって,英語の本来語への思慕や借用語の嫌悪という純粋主義的な態度が世の注目を浴びるには,まだ時代が早かったものと思われる.それでも,この中英語期の早熟な純粋主義的批判は,後世の苛烈な批判の前段階として,確かに英語史上に位置づけられるものではあるだろう.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2015-01-26 Mon

■ #2100. 近代フランス語に基づく「語源的綴字」 [french][spelling][etymological_respelling][lmode]

初期近代英語の語源的綴字に関する話題は,通常,ルネサンス期のラテン語熱の所産であるとして語られる.仰ぎ見るべきお手本は,優に千年以上踏み固められてきたラテン語の綴字であり,英語もフランス語から譲り受けた「崩れた」形ではなく,少しでもラテン語本家の形に近づくべきだ,と.そうしてみると,近代英語は,直前数世紀のあいだ一目おいていたフランス語に追いつき,さらに追い越さんという勢いのなかで,さらなる高みにあるラテン語の威光を目指していたということになる.では,フランス語はもはや英語の綴字に模範を与えるような存在ではなくなっていたということだろうか.例えば,フランス借用語などにおいてフランス語の綴字に基づいた綴りなおしという現象はなかったのだろうか.

ラテン語に基づいた語源的綴字の影で目立たないが,そのような例は後期近代英語期に見られる.「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1]) 及び「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]) の記事でみたように,17世紀後半から18世紀にかけては,フランス様式やフランス文化が大流行した時期である.この頃英語へ借用されたフランス単語は,フランス語の綴字と発音のままで受け入れられ現在に至っているものが多いという特徴をもつが,より早い段階に英語へ借用されていたフランス単語が,改めて近代フランス語風に綴りなおされるという例もあった.

例えば,Horobin (134) は,bisket が biscuit へ,blew が blue へ綴りなおされたのは,当時のフランス語綴字が参照されたためとしている.実際には,biscuit は19世紀の綴りなおし,blue は18世紀からの綴じなおしである.ここで起こったことは同時代のフランス語の綴字を参照して綴りなおしたにすぎず,ラテン語の事例にならって「語源的綴字」と呼ぶのは必ずしも正確ではなく,むしろフランス語からの再借用と称しておくべきものかもしれないが,表面的には「語源的綴字」と似た側面があり興味深い.最終的にフランス語式の綴字が採られて定着した例として「#299. explain になぜ <i> があるのか」 ([2010-02-20-1]),「#300. explain になぜ <i> があるのか (2)」 ([2010-02-21-1]) で取り上げた <explain> もあるので,参照されたい.

だが,いかんせん例は少ないように思われる.ほかの手段で調べれば類例がもっと出てくるかもしれないが,そのために調査すべき期間は17世紀後半から19世紀前半くらいまでの間というところか.というのは,近代英語期のフランス語借用の流行期は18世紀がピークであり,世紀末のフランス革命以後は,貴族の威信が下落し,中流階級が台頭してくるにしたがってフランス様式の流行は下火になったからだ.

語源的綴字という実践の背後にある原動力の1つは,流行と威信の言語に,せめて綴定上だけでもあやかりたいと思う憧れの気持ちである.その点においては,初期近代英語のラテン語ベースの語源的綴字も後期近代英語のフランス語ベースの「語源的綴字」も共通している.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-12-29 Mon

■ #2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非 [lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][register][synonym][romancisation][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙の三層構造について「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]),「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1]) など,多くの記事で言及してきた.「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]) でみたように,語彙の三層構造ゆえに英語は非民主的な言語であるとすら言われることがあるが,英語語彙のこの特徴は見方によっては是とも非となる類いのものである.

Jespersen (121--39) がその是と非の要点を列挙している.まず,長所から.

(1) 英仏羅語に由来する類義語が多いことにより,意味の "subtle shades" が表せるようになった.

(2) 文体的・修辞的な表現の選択が可能になった.

(3) 借用語には長い単語が多いので,それを使う話者は考慮のための時間を確保することができる.

(4) ラテン借用語により国際性が担保される.

まず (1) と (2) は関連しており,表現力の大きさという観点からは確かに是とすべき項目だろう.日本語語彙の三層構造と比較すれば,表現者にとってのメリットは実感されよう.しかし,聞き手や学習者にとっては厄介な特徴ともいえ,その是非はあくまで相対的なものであるということも忘れてはならない.(3) はおもしろい指摘である.非母語話者として英語を話す際には,ミリ秒単位(?)のごく僅かな時間稼ぎですら役に立つことがある.長い単語で時間稼ぎというのは,状況にもよるが,戦略としては確かにあるのではないか.(4) はラテン借用語だけではなくギリシア借用語についても言えるだろう.関連して「#512. 学名」 ([2010-09-21-1]) や「#1694. 科学語彙においてギリシア語要素が繁栄した理由」 ([2013-12-16-1]) も参照されたい.

次に,Jespersen が挙げている短所を列挙する.

(5) 不必要,不適切なラテン借用語の使用により,意味の焦点がぼやけることがある.

(6) 発音,綴字,派生語などについて記憶の負担が増える.例えば,「#859. gaseous の発音」 ([2011-09-03-1]) の各種のヴァリエーションの問題や「#573. 名詞と形容詞の対応関係が複雑である3つの事情」 ([2010-11-21-1]) でみた labyrinth の派生形容詞の問題などは厄介である.

(7) 科学の日常化により,関連語彙には国際性よりも本来語要素による分かりやすさが求められるようになってきている.例えば insomnia よりも sleeplessness のほうが分かりやすく有用であるといえる.

(8) 非本来語由来の要素の導入により,派生語間の強勢位置の問題が生じた (ex. Cánada vs Canádian) .

(9) ラテン語の複数形 (ex. phenomena, nuclei) が英語へもそのまま持ち越されるなどし,形態論的な統一性が崩れた.

(10) 語彙が非民主的になった.

是と非とはコインの表裏の関係にあり,絶対的な判断は下しにくいことがわかるだろう.結局のところ,英語の語彙構造それ自体が問題というよりは,それを使用者がいかに使うかという問題なのだろう.現代英語の語彙構造は,各時代の言語接触などが生み出してきた様々な語彙資源の歴史的堆積物にすぎず,それ自体に良いも悪いもない.したがって,そこに民主的あるいは非民主的というような評価を加えるということは,評価者が英語語彙を見る自らの立ち位置を表明しているということである.Jespersen (139) は次の総評をくだしている.

While the composite character of the language gives variety and to some extent precision to the style of the greatest masters, on the other hand it encourages an inflated turgidity of style. . . . [W]e shall probably be near the truth if we recognize in the latest influence from the classical languages 'something between a hindrance and a help'.

日本語において明治期に大量に生産された(チンプン)漢語や20世紀にもたらされた夥しいカタカナ語にも,似たような評価を加えることができそうだ(「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) とそこに張ったリンク先を参照).

英語という言語の民主性・非民主性という問題については「#134. 英語が民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2009-09-08-1]),「#1366. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由」 ([2013-01-22-1]),「#1845. 英語が非民主的な言語と呼ばれる理由 (2)」 ([2014-05-16-1]) で取り上げたので,そちらも参照されたい.また,英語語彙のロマンス化 (romancisation) に関する評価については「#153. Cosmopolitan Vocabulary は Asset か?」 ([2009-09-27-1]) や「#395. 英語のロマンス語化についての評」 ([2010-05-27-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2014-12-15 Mon

■ #2058. 語源的綴字,表語文字,黙読習慣 (1) [french][etymological_respelling][latin][grammatology][manuscript][scribe][silent_reading][renaissance][hfl]

一昨日の記事「#2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1)」 ([2014-12-13-1]) で,フランス語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) が同音異義語どうしを区別するのに役だったという点に触れた.フランス語において語源的綴字がそのような機能を得たということは,別の観点から言えば,フランス語の書記体系が表音 (phonographic) から表語 (logographic) へと一歩近づいたとも表現できる.このような表語文字体系への接近が,英語では中英語から近代英語にかけて生じていたのと同様に,フランス語では古仏語から中仏語にかけて生じていた.むしろフランス語での状況の方が,英語より一歩も二歩も先に進んでいただろう.(cf. 「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1]),「#1940. 16世紀の綴字論者の系譜」 ([2014-08-19-1]),「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1]).)

フランス語の状況に関しては,当然ながら英語史ではなくフランス語史の領域なので,フランス語史概説書に当たってみた.以下,Perret (138) を引用しよう.まずは,古仏語の書記体系は表音的であるというくだりから.

L'ancien français : une écriture phonétique

. . . . dans la mesure où l'on disposait de graphèmes pour rendre les son que l'on entendait, l'écriture était simplement phonétique (feré pour fairé, souvent kí pour quí) . . . .

Perret (138--39) は続けて,中仏語の書記体系の表語性について次のように概説している.

Le moyen français : une écriture idéographique

À partir du XIIIe siècle, la transmission des textes cesse d'être uniquement orale, la prose commence à prendre de l'importance : on écrit aussi des textes juridiques et administratifs en français. Avec la prose apparaît une ponctuation très différente de celle que nous connaissons : les textes sont scandés par des lettrines de couleur, alternativement rouges et bleues, qui marquent le plus souvent des débuts de paragraphes, mais pas toujours, et des points qui correspondent à des pauses, généralement en fin de syntagme, mais pas forcément en fin de phrase. Les manuscrits deviennent moins rares et font l'objet d'un commerce, ils ne sont plus recopiés par des moines, mais des scribes séculiers qui utilisent une écriture rapide avec de nombreuses abréviations. On change d'écriture : à l'écriture caroline succèdent les écritures gothique et bâtarde dans lesquelles certains graphèmes (les u, n et m en particulier) sont réduits à des jambages. C'est à partir de ce moment qu'apparaissent les premières transformations de l'orthographe, les ajouts de lettres plus ou moins étymologiques qui ont parfois une fonction discriminante. C'est entre le XIVe et le XVIe siècle que s'imposent les orthographes hiver, pied, febve (où le b empêche la lecture ‘feue’), mais (qui se dintingue ainsi de mes); c'est alors aussi que se développent le y, le x et le z à la finale des mots. Mais si certains choix étymologiques ont une fonction discrminante réelle, beaucoup semblent n'avoir été ajoutés, pour le plaisir des savants, qu'afin de rapprocher le mot français de son étymon latin réel ou supposé (savoir s'est alors écrit sçavoir, parce qu'on le croyait issu de scire, alors que ce mot vient de sapere). C'est à ce moment que l'orthographe française devient de type idéographique, c'est-à-dire que chaque mot commence à avoir une physionomie particulière qui permet de l'identifier par appréhension globale. La lecture à haute voix n'est plus nécessaire pour déchiffrer un texte, les mots peuvent être reconnus en silence par la méthode globale.

引用の最後にあるように,表語文字体系の発達を黙読習慣の発達と関連づけているところが実に鋭い洞察である.声に出して読み上げる際には,発音に素直に結びつく表音文字体系のほうがふさわしいだろう.しかし,音読の機会が減り,黙読が通常の読み方になってくると,内容理解に直結しやすいと考えられる表語(表意)文字体系がふさわしいともいえる (cf. 「#1655. 耳で読むのか目で読むのか」 ([2013-11-07-1]),「#1829. 書き言葉テクストの3つの機能」 ([2014-04-30-1])) .音読から黙読への転換が,表音文字から表語文字への転換と時期的におよそ一致するということになれば,両者の関係を疑わざるを得ない.

フランス語にせよ英語にせよ,語源的綴字はルネサンス期のラテン語熱との関連で論じられるのが常だが,文字論の観点からみれば,表音から表語への書記体系のタイポロジー上の転換という問題ともなるし,書物文化史の観点からみれば,音読から黙読への転換という問題ともなる.<doubt> の <b> の背後には,実に学際的な世界が広がっているのである.

・ Perret, Michèle. Introduction à l'histoire de la langue française. 3rd ed. Paris: Colin, 2008.

2014-12-14 Sun

■ #2057. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (2) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][scribe][anglo-norman][renaissance]

昨日の記事に引き続き,英仏両言語における語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の関係について.Scragg (52--53) は,次のように述べている.

Throughout the Middle Ages, French scribes were very much aware of the derivation of their language from Latin, and there were successive movements in France for the remodelling of spelling on etymological lines. A simple example is pauvre, which was written for earlier povre in imitation of Latin pauper. Such spellings were particularly favoured in legal language, because lawyers' clerks were paid for writing by the inch and superfluous letters provided a useful source of income. Since in France, as in England, conventional spelling grew out of the orthography of the chancery, at the heart of the legal system, many etymological spellings became permanently established. Latin was known and used in England throughout the Middle Ages, and there was a considerable amount of word-borrowing from it into English, particularly in certain registers such as that of theology, but since the greater part of English vocabulary was Germanic, and not Latin-derived, it is not surprising that English scribes were less affected by the etymologising movements than their French counterparts. Anglo-Norman, the dialect from which English derived much of its French vocabulary, was divorced from the mainstream of continental French orthographic developments, and any alteration in the spelling of Romance elements in the vocabulary which occurred in English in the fourteenth century was more likely to spring from attempts to associate Anglo-Norman borrowings with Parisian French words than from a concern with their Latin etymology. Etymologising by reference to Latin affected English only marginally until the Renaissance thrust the classical language much more positively into the centre of the linguistic arena.

重要なポイントをまとめると,

(1) 中世フランス語におけるラテン語源を参照しての文字の挿入は,写字生の小金稼ぎのためだった.

(2) フランス語に比べれば英語にはロマンス系の語彙が少なく(相対的にいえば確かにその通り!),ラテン語源形へ近づけるべき矯正対象となる語もそれだけ少なかったため,語源的綴字の過程を経にくかった,あるいは経るのが遅れた (cf. 「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1])) .

(3) 14世紀の英語の語源的綴字は,直接ラテン語を参照した結果ではなく,Anglo-Norman から離れて Parisian French を志向した結果である.

(4) ラテン語の直接の影響は,本格的にはルネサンスを待たなければならなかった.

では,なぜルネサンス期,より具体的には16世紀に,ラテン語源形を直接参照した語源的綴字が英語で増えたかという問いに対して,Scragg (53--54) はラテン語彙の借用がその時期に著しかったからである,と端的に答えている.

As a result both of the increase of Latinate vocabulary in English (and of Greek vocabulary transcribed in Latin orthography) and of the familiarity of all literate men with Latin, English spelling became as affected by the etymologising process as French had earlier been.

確かにラテン語彙の大量の流入は,ラテン語源を意識させる契機となったろうし,語源的綴字への影響もあっただろうとは想像される.しかし,語源的綴字の潮流は前時代より歴然と存在していたのであり,単に16世紀のラテン語借用の規模の増大(とラテン語への親しみ)のみに言及して,説明を片付けてしまうのは安易ではないか.英語における語源的綴字の問題は,より大きな歴史的文脈に置いて理解することが肝心なように思われる.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2014-12-13 Sat

■ #2056. 中世フランス語と英語における語源的綴字の関係 (1) [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][hypercorrection][renaissance][hfl]

中英語期から近代英語期にかけての英語の語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の発生と拡大の背後には,対応するフランス語での語源的綴字の実践があった.このことについては,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]),「#1156. admiral の <d>」 ([2012-06-26-1]),「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]),「#1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって」 ([2014-08-21-1]) などの記事で触れてきたとおりである.

したがって,英語におけるこの問題を突き詰めようとすれば,フランス語史を参照せざるをえない.14--16世紀の中世フランス語の語源的綴字の実践について,Zink (24--25) を引用しよう.

Latinisation et surcharge graphique. --- L'idée de rapprocher les mots français de leurs étymons latins ne date pas de la Renaissance. Le mouvement de latinisation a pris naissance à la fin du XIIIe siécle avec les emprunts opérés par la langue juridique au droit romain sous forme de calques à peine francisés.... Parti du vocabulaire savant, il a gagné progressivement les mots courants de l'ancien fonds. Il ne pouvait s'agir dans ce dernier cas que de réfections purement graphiques, sans incidence sur la prononciation ; aussi est-ce moins le vocalisme qui a été retouché que le consonantisme par l'insertion de graphèmes dans les positions où on ne les prononçait plus : finale et surtout intérieure implosive.

Ainsi s'introduisent avec le flot des emprunts savants : adjuger, exception (XIIIe s.) ; abstraire, adjonction, adopter, exemption, subjectif, subséquent. . . (mfr., la prononciation actuelle datant le plus souvent du XVIe s.) et l'on rhabille à l'antique une foule de mots tels que conoistre, destre, doter, escrit, fait, nuit, oscur, saint, semaine, soissante, soz, tens en : cognoistre, dextre, doubter, escript, faict, nuict, obscur, sainct, sepmaine, soixante, soubz, temps d'après cognoscere, dextra, dubitare, scriptum, factum, noctem, obscurum, sanctum, septimana, sexaginta, subtus, tempus.

Le souci de différencier les homonymes, nombreux en ancien français, entre aussi dans les motivations et la langue a ratifié des graphies comme compter (qui prend le sens arithmétique au XVe s.), mets, sceau, sept, vingt, bien démarqués de conter, mais/mes, seau/sot, sait, vint.

Toutefois, ces correspondances supposent une connaissance étendue et précise de la filiation des mot qui manque encore aux clercs du Moyen Age, d'où des tâtonnements et des erreurs. Les rapprochements fautifs de abandon, abondant, oster, savoir (a + bandon, abundans, obstare, sapere) avec habere, hospitem (!), scire répandent les graphies habandon, habondant, hoster, sçavoir (à toutes les formes). . . .

要点としては,(1) フランス語ではルネサンスに先立つ13世紀末からラテン語借用が盛んであり,それに伴ってラテン語に基づく語源的綴字も現われだしていたこと,(2) 語末と語中の子音が脱落していたところに語源的な子音字を復活させたこと,(3) 語源的綴字を示すいくつかの単語が英仏両言語において共通すること,(4) フランス語の場合には語源的綴字は同音異義語どうしを区別する役割があったこと,(5) フランス語でも語源的綴字に基づき,それを延長させた過剰修正がみられたこと,が挙げられる.これらの要点はおよそ英語の語源的綴字を巡る状況にもあてはまり,英仏両言語の類似現象が関与していること,もっと言えばフランス語が英語へ影響を及ぼしたことが示唆される.(5) に挙げた過剰修正 (hypercorrection) の英語版については,「#1292. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ」 ([2012-11-09-1]),「#1899. 中英語から近代英語にかけての h の位置づけ (3)」 ([2014-07-09-1]),「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) も参照されたい.

語源的綴字を巡る状況に関して英仏語で異なると思われるのは,上記 (4) だろう.フランス語では,語源的綴字の導入は,同音異義語 (homonymy) を区別するのに役だったという.換言すれば,書記において同音異義衝突 (homonymic_clash) を避けるために,語源的原則に基づいて互いに異なる綴字を導入したということである.ラテン語からロマンス諸語へ至る過程で生じた数々の音韻変化の結果,フランス語では単音節の同音異義語が大量に生じるに至った.この問題を書記において解決する策として,語源的綴字が利用されたのである.日本語のひらがなで「こうし」と書いてもどの「こうし」か区別が付かないので,漢字で「講師」「公私」「嚆矢」などと書き分ける状況と似ている.ここにおいてフランス語の書記体系は,従来の表音的なものから,表語的なものへと一歩近づいたといえるだろう.

英語では同音異義衝突を避けるために語源的綴字を導入するという状況はなかったように思われるが,機能主義的な語源的綴字の動機付けという点については,もう少し注意深く考察する価値がありそうだ.

・ Zink, Gaston. ''Le moyen françis (XIVe et XV e siècles)''. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1990.[sic]

2014-12-04 Thu

■ #2047. ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義 [norman_conquest][french][contact][speed_of_change]

「#1171. フランス語との言語接触と屈折の衰退」 ([2012-07-11-1]),「#1208. フランス語の英文法への影響を評価する」 ([2012-08-17-1]),「#1884. フランス語は中英語の文法性消失に関与したか」 ([2014-06-24-1]) で論じたように,ノルマン征服の英語史上の意義は主として間接的で社会言語学的なものである.語彙や書記には確かに少なからぬ影響を直接に与えたが,文法や音声への影響はあったとしても僅かである (cf. 「#204. 非人称構文」 ([2009-11-17-1]),「#1815. 不定代名詞 one の用法はフランス語の影響か?」 ([2014-04-16-1])) .

ノルマン征服の最大の貢献は,アングロサクソン社会から英語の書記規範を奪い去り,英語を話し言葉の世界へ解き放ったことであると私は考えている.それによって,英語は自由闊達,天衣無縫に言語変化を遂げることができるようになった.上掲の[2012-07-11-1]と[2012-08-17-1]の記事で引用した内容と重複するが,ブルシェ (42--43) もまたノルマン征服のこの役割を正当に評価している.

1066年に起ったある大きな出来事が,必然的に潜伏期間を伴って,その影響を十分に与えつつあった.それはむろん「ノルマン人による英国征服」 (conquête normande) のことであり,それによって二つの言語,英語とフランス語が接触し,政治的・社会学的激動が引き起こされた.それから長い間,金持ちと支配階級は英語を話さなくなるのである.11世紀中頃までに既に始まっていたいくつかの言語現象も,たとえ何が起ころうとも拡大したではあろうが,この「ノルマン人による英国征服」が英語の将来に決定的な影響を与えたことは間違いない.1300年頃までにいくつかの(注目すべき)例外を別にして,大半の文学作品,大多数の書物は以前としてアングロ・ノルマン語あるいはラテン語で書かれていた.そのため土着言語である英語の威信が低下し,「ノルマン人による英国征服」以降英語の主要な媒体は話し言葉になったのである.話し言葉は書き言葉に比べ保守性に乏しく,より流動的で,改革に応じることのできる言語形態である.長い進化過程の果てに英語が文化交流や公式の場で活躍しうる言語としての威厳を取り戻すことができた時,使用される書き言葉は「その時代に話し言葉が到達した」発達段階を反映していると考えられる.要するに,保守的な書記規範の歯止めが無くなったのである.それは方言の多様性と下位区分の明白な増加に現われている(しかし,この点においては慎重でなければならない.なぜなら,古英語の段階で使用できる言語材料は,その時代の方言の真の多様性を正しく例証しているとは限らないからである).保守的な書記規範の歯止めが無くなったことは,文学と詩の言語使用域 (registre) から人為的に慣用の中に組み込まれていた多数の語が消滅したことや,特に系列的変化 (paradigme) や屈折語尾 (désinence) の総体がかなり徹底して簡略化されたことにも現われている.

ブルシェの著書は英語の正書法の歴史だが,音声史と外面史をも含みこんだ専門的な英語史の良書だと思う.

・ ジョルジュ・ブルシェ(著),米倉 綽・内田 茂・高岡 優希(訳) 『英語の正書法――その歴史と現状』 荒竹出版,1999年.

2014-11-19 Wed

■ #2032. 形容詞語尾 -ive [etymology][suffix][french][loan_word][spelling][pronunciation][verners_law][consonant][stress][gsr][adjective]

フランス語を学習中の学生から,こんな質問を受けた.フランス語では actif, effectif など語尾に -if をもつ語(本来的に形容詞)が数多くあり,男性形では見出し語のとおり -if を示すが,女性形では -ive を示す.しかし,これらの語をフランス語から借用した英語では -ive が原則である.なぜ英語はフランス語からこれらの語を女性形で借用したのだろうか.

結論からいえば,この -ive はフランス語の対応する女性形語尾 -ive を直接に反映したものではない.英語は主として中英語期にフランス語からあくまで見出し語形(男性形)の -if の形で借用したのであり,後に英語内部での音声変化により無声の [f] が [v] へ有声化し,その発音に合わせて -<ive> という綴字が一般化したということである.

中英語ではこれらのフランス借用語に対する優勢な綴字は -<if> である.すでに有声化した -<ive> も決して少なくなく,個々の単語によって両者の間での揺れ方も異なると思われるが,基本的には -<if> が主流であると考えられる.試しに「#1178. MED Spelling Search」 ([2012-07-18-1]) で,"if\b.*adj\." そして "ive\b.*adj\." などと見出し語検索をかけてみると,数としては -<if> が勝っている.現代英語で頻度の高い effective, positive, active, extensive, attractive, relative, massive, negative, alternative, conservative で調べてみると,MED では -<if> が見出し語として最初に挙がっている.

しかし,すでに後期中英語にはこの綴字で表わされる接尾辞の発音 [ɪf] において,子音 [f] は [v] へ有声化しつつあった.ここには強勢位置の問題が関与する.まずフランス語では問題の接尾辞そのもに強勢が落ちており,英語でも借用当初は同様に接尾辞に強勢があった.ところが,英語では強勢位置が語幹へ移動する傾向があった (cf. 「#200. アクセントの位置の戦い --- ゲルマン系かロマンス系か」 ([2009-11-13-1]),「#718. 英語の強勢パターンは中英語期に変質したか」 ([2011-04-15-1]),「#861. 現代英語の語強勢の位置に関する3種類の類推基盤」 ([2011-09-05-1]),「#1473. Germanic Stress Rule」 ([2013-05-09-1])) .接尾辞に強勢が落ちなくなると,末尾の [f] は Verner's Law (の一般化ヴァージョン)に従い,有声化して [v] となった.verners_law と子音の有声化については,特に「#104. hundred とヴェルネルの法則」 ([2009-08-09-1]) と「#858. Verner's Law と子音の有声化」 ([2011-09-02-1]) を参照されたい.

上記の音韻環境において [f] を含む摩擦音に有声化が生じたのは,中尾 (378) によれば,「14世紀後半から(Nではこれよりやや早く)」とある.およそ同時期に,[s] > [z], [θ] > [ð] の有声化も起こった (ex. is, was, has, washes; with) .

上に述べた経緯で,フランス借用語の -if は後に軒並み -ive へと変化したのだが,一部例外的に -if にとどまったものがある.bailiff (執行吏), caitiff (卑怯者), mastiff (マスチフ), plaintiff (原告)などだ.これらは,古くは [f] と [v] の間で揺れを示していたが,最終的に [f] の音形で標準化した少数の例である.

以上を,Jespersen (200--01) に要約してもらおう.

The F ending -if was in ME -if, but is in Mod -ive: active, captive, etc. Caxton still has pensyf, etc. The sound-change was here aided by the F fem. in -ive and by the Latin form, but these could not prevail after a strong vowel: brief. The law-term plaintiff has kept /f/, while the ordinary adj. has become plaintive. The earlier forms in -ive of bailiff, caitif, and mastiff, have now disappeared.

冒頭の質問に改めて答えれば,英語 -ive は直接フランス語の(あるいはラテン語に由来する)女性形接尾辞 -ive を借りたものではなく,フランス語から借用した男性形接尾辞 -if の子音が英語内部の音韻変化により有声化したものを表わす.当時の英語話者がフランス語の女性形接尾辞 -ive にある程度見慣れていたことの影響も幾分かはあるかもしれないが,あくまでその関与は間接的とみなしておくのが妥当だろう.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

2014-09-15 Mon

■ #1967. 料理に関するフランス借用語 [loan_word][french][lexicology][norman_conquest][semantic_field][recipe]

昨日の記事「#1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー」 ([2014-09-14-1]) で,英語の料理や飲食物に関する語彙には,歴史的にフランス借用語が幅を利かせてきたことを確認した.その背景にあるのは,疑いなく1066年のノルマン・コンクェエストである.それ以降,「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]) で典型的に知られているように,アングロサクソン系の大多数の庶民は家畜の世話に追われ,フランス系の上流階級はフランスの料理に舌鼓を打った.イングランドにおいてフランス料理は,単においしいだけでなく,権威や洗練の象徴として社会的な含意をもっていた.

動物とその肉料理に関する sheep / mutton; ox / beef; pig / pork, bacon, gammon; calf / veal; boar / brawn; fowl / poultry の英仏語彙の対立はよく知られているが,ほかにもフランス借用語が料理に関する意味場を広く占めている証拠はたくさんある.昨日の記事で引用した Hughes は,"The sociology of food" (117--20) と題する節で,興味深い事例を列挙している.

まず,動物の可食部位で上質な部位と下等な部位とで呼び名が異なるという事実がある.haunch, joint, cutlet はフランス語だが,brains, tongue, shank は英語だ.ある程度豪華な食事を表わす dinner, supper, banquet はフランス語だが,質素な breakfast は英語だ(なお,lunch は16世紀末に初出し,昼食の意では19世紀から).火を通す調理法は「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) の COOK の配下に挙げた boil, broil, roast, grill, fry など多くの動詞がフランス語だ.スープ,デザート,調味料など風味の素材も然り (ex. soup, potage, sauce, dessert, mustard, cream, ginger, liquorice, flan, pasty, claret, biscuit) .アングロ・サクソンの食文化のひもじさが悲しいほどだ.

中世のご馳走を用意する係の名前にもフランス語が目立つ.steward (給仕長)こそ英語だが(sty + ward で「豚小屋世話人」というのが皮肉),marshal (接待係),sewer (配膳方),pantler (食料貯蔵室管理人),butler (執事)はフランス語である.下働きの scullion (皿洗い男),blackguard (召使い),pot-boy (ボーイ)はいずれも英語である.

最後に,15世紀のレシピの英文を覗いてみよう.Hughes (118) からの再引用だが,イタリック体の語がフランス借用語である.いかに料理の意味場がフランス語かぶれしているかが分かるだろう.

Oystres in grauey

Take almondes, and blanche hem, and grinde hem and drawe þorgh a streynour with wyne, and with goode fressh broth into gode mylke, and sette hit on þe fire and lete boyle; and cast therto Maces, clowes, Sugur, pouder of Ginger, and faire parboyled oynons mynced; And þen take faire oystres, and parboile hem togidre in faire water; And then caste hem ther-to, And let hem boyle togidre til þey ben ynowe; and serve hem forth for gode potage.

いかにもフランス語かぶれしている.しかし,かぶれていなかったら,今でさえ評価されることの少ないイングランドの食事情は,さらに貧しいものとなったに違いない.人たるもの,食の分野において purism の議論はあり得ない.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-14 Sun

■ #1966. 段々おいしくなってきた英語の飲食物メニュー [loan_word][french][history][lexicology]

Hughes (119) に,眺めているだけでおいしくなってくる英語の "A historical menu" が掲載されている.古英語期から現代英語期までに次々と英語へ入ってきた飲食物を表わす借用語が,時代順に並んでいる.Hughes は現代から古英語へと遡るように一覧を提示しており,昔の食べ物は素朴だったなあという感慨を得るにはよいのだが,下から読んだほうが圧倒的に食欲が増すので,そのように読むことをお勧めしたい.

| Food | Drink | |

|---|---|---|

| pesto, salsa, sushi | ||

| tacos, quiche, schwarma | ||

| pizza, osso bucco | Chardonnay | |

| 1900 | paella, tuna, goulash | |

| hamburger, mousse, borscht | Coca Cola | |

| grapefruit, éclair, chips | soda water | |

| bouillabaisse, mayonnaise | ||

| ravioli, crêpes, consommé | riesling | |

| 1800 | spaghetti, soufflé, bechamel | tequila |

| ice cream | ||

| kipper, chowder | ||

| sandwich, jam | seltzer | |

| meringue, hors d'oeuvre, welsh rabbit | whisky | |

| 1700 | avocado, pâté | gin |

| muffin | port | |

| vanilla, mincemeat, pasta | champagne | |

| salmagundi | brandy | |

| yoghurt, kedgeree | sherbet | |

| 1600 | omelette, litchi, tomato, curry, chocolate | tea, sherry |

| banana, macaroni, caviar, pilav | coffee | |

| anchovy, maize | ||

| potato, turkey | ||

| artichoke, scone | sillabub | |

| 1500 | marchpane (marzipan) | |

| whiting, offal, melon | ||

| pineapple, mushroom | ||

| salmon, partridge | ||

| Middle English | venison, pheasant | muscatel |

| crisp, cream, bacon | rhenish (rhine wine) | |

| biscuit, oyster | claret | |

| toast, pastry, jelly | ||

| ham, veal, mustard | ||

| beef, mutton, brawn | ||

| sauce, potage | ||

| broth, herring | ||

| meat, cheese | ale | |

| Old English | cucumber, mussel | beer |

| butter, fish | wine | |

| bread | water |

予想通りフランス借用語が多いものの,全体的にはバラエティ豊かで多国籍風である.

料理の分野におけるフランス語については,ほかにも「#61. porridge は愛情をこめて煮込むべし」 ([2009-06-28-1]),「#331. 動物とその肉を表す英単語」 ([2010-03-24-1]),「#332. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」の神話」 ([2010-03-25-1]),「#1583. swine vs pork の社会言語学的意義」 ([2013-08-27-1]),「#1603. 「動物とその肉を表す英単語」を最初に指摘した人」 ([2013-09-16-1]),「#678. 汎ヨーロッパ的な18世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2011-03-06-1]),「#1792. 18--20世紀のフランス借用語」 ([2014-03-24-1]),「#1667. フランス語の影響による形容詞の後置修飾 (1)」 ([2013-11-19-1]),「#1210. 中英語のフランス借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-19-1]) を参照.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-09-08 Mon

■ #1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造 [register][lexicology][loan_word][latin][french][greek][semantics][polysemy][lexical_stratification]

英語語彙に特徴的な三層構造について,「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1]),「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1]),「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1]) などの記事でみてきた.三層構造という表現が喚起するのは,上下関係と階層のあるビルのような建物のイメージかもしれないが,ビルというよりは,裾野が広く頂点が狭いピラミッドのような形を想像するほうが妥当である.つまり,下から,裾野の広い低階層の本来語彙,やや狭まった中階層のフランス語彙,そして著しく狭い高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙というイメージだ.

ピラミッドの比喩が適切なのは,1つには,高階層のラテン・ギリシア語彙のもつ特権的な地位と威信がよく示されているからだ.社会言語学的,文体的に他を圧倒するポジションについていることは,ビル型よりもピラミッド型のほうがよく表現できる.

2つ目として,それぞれの語彙の頻度が,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積として表現できるからである.昨日の記事「#1959. 英文学史と日本文学史における主要な著書・著者の用いた語彙における本来語の割合」 ([2014-09-07-1]) でみたように,話し言葉のみならず書き言葉においても,本来語彙の頻度は他を圧倒している(なお,この分布は,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) でみたように,現代日本語においても同様だった).対照的に,高階層の語彙は頻度が低い.個々の語については反例もあるだろうが,全体的な傾向としては,各階層の頻度と面積とは対応する.もっとも,各階層の語彙量(異なり語数)ということでいえば,必ずしもそれがピラミッドの面積に対応するわけでない.最頻100語(cf. 「#309. 現代英語の基本語彙100語の起源と割合」 ([2010-03-02-1]) と最頻600語(cf. 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1]))で見る限り,語彙量と面積はおよそ対応しているが,10000語というレベルで調査すると,「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1]) でみたように,上で前提としてきた3階層の上下関係は崩れる.

ピラミッドの比喩が有効と考えられる3つ目の理由は,ピラミッドにおける各階層の面積が,頻度のみならず,構成語のもつ意味と用法の広さにも対応しているからだ.本来語は相対的に卑近であり頻度も高いが,そればかりでなく,多義であり,用法が多岐にわたる.基本的な語義が同じ「与える」でも,本来語 give は派生的な語義も多く極めて多義だが,ラテン借用語 donate は語義が限定されている.また,give は文型として SVOiOd も SVOd to Oi も取ることができる(すなわち dative shift が可能だ)が,donate は後者の文型しか許容しない.ほかには「#112. フランス・ラテン借用語と仮定法現在」 ([2009-08-17-1]) で示唆したように,語彙階層が統語的な振る舞いに関与していると疑われるケースがある.

この第3の観点から,Hughes (43) は,次のようなピラミッド構造を描いた.

![]()

上記の3点のほかにも,各階層の面積と語の理解しやすさ (comprehensibility) が関係しているという見方もある.結局のところ,語彙階層は,基本性,日常性,文体的威信の低さ,頻度,意味・用法の広さといった諸相と相関関係にあるということだろう.ピラミッドの比喩は巧みである.

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

2014-08-21 Thu

■ #1942. 語源的綴字の初例をめぐって [etymological_respelling][spelling][french][latin][hart]

昨日の記事「#1941. macaronic code-switching としての語源的綴字?」 ([2014-08-20-1]) に引き続き,etymological_respelling の話題.英語史では語源的綴字は主に16--17世紀の話題として認識されている(cf. 「#1387. 語源的綴字の採用は17世紀」 ([2013-02-12-1])).しかし,それより早い例は14--15世紀から確認されているし,「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1]),「#1790. フランスでも16世紀に頂点を迎えた語源かぶれの綴字」 ([2014-03-22-1]) でみたように,お隣フランスでもよく似た現象が13世紀後半より生じていた.実際にフランスでも語源的綴字は16世紀にピークを迎えたので,この現象について,英仏語はおよそ歩調を合わせていたことになる.

フランス語側での語源的綴字について詳しく調査していないが,Miller (211) は14世紀終わりからとしている.

Around the end of C14, French orthography began to be influenced by etymology. For instance, doute 'doubt' was written doubte. Around the same time, such etymologically adaptive spellings are found in English . . . ., especially by C16. ME doute [?a1200] was altered to doubt by confrontation with L dubitō and/or contemporaneous F doubte, and the spelling remained despite protests by orthoepists including John Hart (1551) that the word contains an unnecessary letter . . . .

フランス語では以来 <doubte> が続いたが,17世紀には再び <b> が脱落し,現代では doute へ戻っている.

では,英語側ではどうか.doubt への <b> の挿入を調べてみると,MED の引用文検索によれば,15世紀から多くの例が挙がるほか,14世紀末の Gower からの例も散見される.

同様に,OED でも <doubt> と引用文検索してみると,15世紀からの例が少なからず見られるほか,14世紀さらには1300年以前の Cursor Mundi からの例も散見された.『英語語源辞典』では,doubt における <b> の英語での挿入は15世紀となっているが,実際にはずっと早くからの例があったことになる.

・ a1300 Cursor M. (Edinb.) 22604 Saint peter sal be domb þat dai,.. For doubt of demsteris wrek [Cott. wreke].

・ 1393 J. Gower Confessio Amantis I. 230 First ben enformed for to lere A craft, which cleped is facrere. For if facrere come about, Than afterward hem stant no doubt.

・ 1398 J. Trevisa tr. Bartholomew de Glanville De Proprietatibus Rerum (1495) xvi. xlvii. 569 No man shal wene that it is doubt or fals that god hath sette vertue in precyous stones.

だが,さすがに初期中英語コーパス ,LAEME からは <b> を含む綴字は見つからなかった.

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-09 Sat

■ #1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図 [indo-european][family_tree][contact][loan_word][borrowing][geolinguistics][linguistic_area][historiography][french][latin][greek][old_norse]

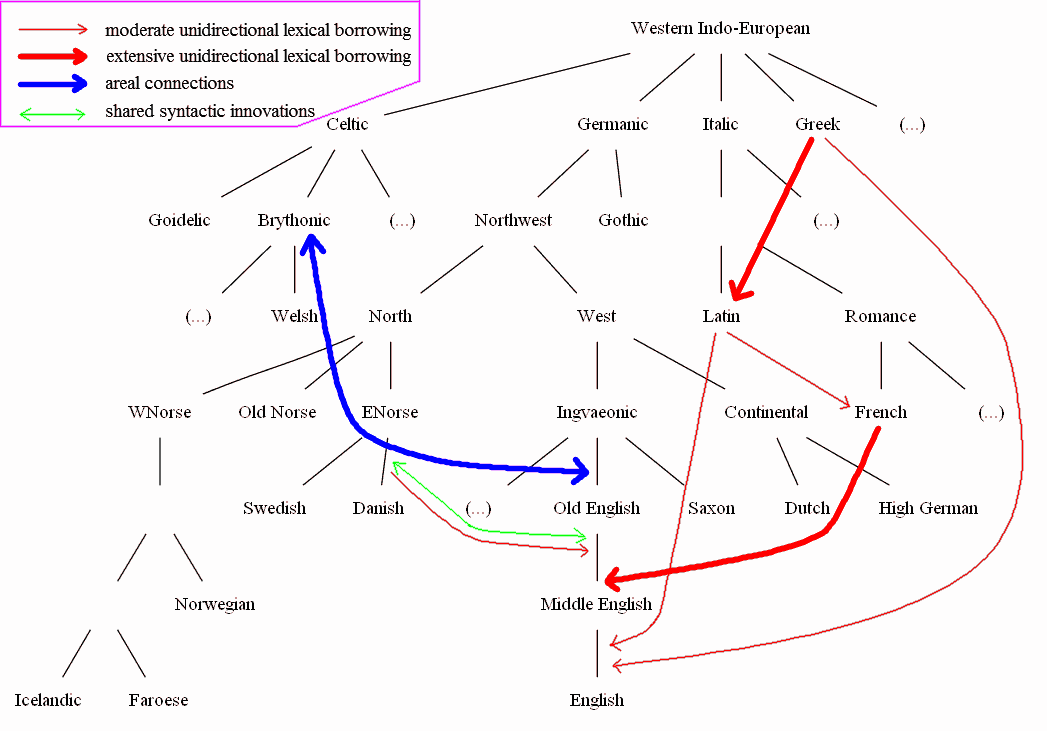

「#999. 言語変化の波状説」 ([2012-01-21-1]),「#1118. Schleicher の系統樹説」 ([2012-05-19-1]),「#1236. 木と波」 ([2012-09-14-1]),「#1925. 語派間の関係を示したインドヨーロッパ語族の系統図」 ([2014-08-04-1]) で触れてきたように,従来の言語系統図の弱点として,言語接触 (language contact) や地理的な隣接関係に基づく言語圏 (linguistic area; cf. 「#1314. 言語圏」 [2012-12-01-1])がうまく表現できないという問題があった.しかし,工夫次第で,系統図のなかに他言語からの影響に関する情報を盛り込むことは不可能ではない.Miller (3) がそのような試みを行っているので,見やすい形に作図したものを示そう.

この図では,英語が歴史的に経験してきた言語接触や地理言語学的な条件がうまく表現されている.特に,主要な言語との接触の性質,規模,時期がおよそわかるように描かれている.まず,ラテン語,フランス語,ギリシア語からの影響が程度の差はあれ一方的であり,語彙的なものに限られることが,赤線の矢印から見て取れる.古ノルド語 (ENorse) との言語接触についても同様に赤線の一方向の矢印が見られるが,緑線の双方向の矢印により,構造的な革新において共通項の少なくないことが示唆されている.ケルト語 (Brythonic) との関係については,近年議論が活発化してきているが,地域的な双方向性のコネクションが青線によって示されている.

もちろん,この図も英語と諸言語との影響の関係を完璧に示し得ているわけではない.例えば,矢印で図示されているのは主たる言語接触のみである(矢印の種類と数を増やして図を精緻化することはできる).また,フランス語との接触について,中英語以降の継続的な関与はうまく図示されていない.それでも,この図に相当量の情報が盛り込まれていることは確かであり,英語史の概観としても役に立つのではないか.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-08-06 Wed

■ #1927. 英製仏語 [waseieigo][french][loan_word]

和製英語について「#1492. 「ゴールデンウィーク」は和製英語か?」 ([2013-05-28-1]) や「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1]) で取り上げ,和製漢語について「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1]) で触れ,英製羅語について「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]) で言及してきた.関連して,今回は「英製仏語」の例を覗いてみよう.Jespersen (101--02) は,「英製仏語」に相当する呼称こそ使っていないが,まさにこの現象について議論している.

Fitzedward Hall in speaking about the recent word aggressive says, 'It is not at all certain whether the French agressif suggested aggressive, or was suggested by it. They may have appeared independently of each other'. The same remark applies to a great many other formations on a French or Latin basis; even if the several components of a word are Romanic, it by no means follows that the word was first used by a Frenchman. On the contrary, the greater facility and the greater boldness in forming new words and turns of expression which characterizes English generally in contradistinction to French, would in many cases speak in favour of the assumption that an innovation is due to an English mind. This I take to be true with regard to dalliance, which is so frequent in ME. (dalyaunce, etc.), while it has not been recorded in French at all. The wide chasm between the most typical English meaning of sensible (a sensible man, a sensible proposal) and those meanings which it shares with French sensible and Lat. sensibilis, probably shows that in the former meaning the word was an independent English formation. Duration as used by Chaucer may be a French word; it then went out of the language, and when it reappeared after the time of Shakespeare it may just as well have been reformed in England as borrowed; duratio does not seem to have existed in Latin. Intensitas is not a Latin word, and intensity is older than intensité.

この一節で Jespersen が「英製仏語」とみなしているものは,aggressive, dalliance, duration, intensity などである.対応する語がフランス語にあったとしても,英単語としてはおそらくイングランドで独立に発生したものだとみている.場合によっては,英製仏語がフランス語へ逆輸入された例もあっただろう.Jespersen は,上記の引用に続く節でも,mutinous, mutiny; cliquery; duty, duteous, dutiable などを英製仏語の候補として挙げている.この種の英製仏語は実際に調べ出せばいくつも出てくるのではないだろうか.

「○製△語」という現象を定義することの難しさについては「#1492. 「ゴールデンウィーク」は和製英語か?」 ([2013-05-28-1]) で見たとおりだが,そのような現象が生じる語史的な背景はおよそ指摘できる.「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1]) で論じたとおり,○言語が△言語からの語彙借用に十分になじんでくると,今度は△言語の語形成をモデルとして自家製の語彙を生み出そうとするのだ.より高次の借用段階に進むといえばよいだろうか.これは,英製仏語のみならず英製羅語,和製英語,和製漢語にも共通に見られる歴史的な過程である.「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]) や「#1878. 国訓,そして記号のリサイクル」 ([2014-06-18-1]) の記事の最後に述べた趣旨を改めて繰り返せば,「○製△語は,興味をそそるトピックとしてしばしば取り上げられるが,通言語的には決して特異な現象ではない」のである.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Growth and Structure of the English Language. 10th ed. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1982.

2014-08-03 Sun

■ #1924. フランス語は中英語の文法性消失に関与したか (2) [gender][french][old_norse][contact][bilingualism][french_influence_on_grammar]

「#1884. フランス語は中英語の文法性消失に関与したか」 ([2014-06-24-1]) で,「当時のイングランドにおける英語と Norman French との2言語使用状況が2つの異なる文法性体系を衝突させ,これが一因となって英語の文法性体系が崩壊することになった」とする説を批判的に紹介した.しかし,その後 Miller (234--35) に上記と少し似た議論をみつけた.Miller 自身も憶測 (speculation) としているが,他の論文においても積極的に論じているようだ.

It is reasonable to speculate that gender was strained by scandinavianization but not abandoned, especially since Danish only reduced masculine and feminine later and in Copenhagen under a different contact situation . . . . Miller . . . suggests that the final loss of gender would most naturally have occurred in the East Midlands, a BUFFER ZONE between French to the south and the Danish-English amalgam to the north, the reason being that the gender systems were completely incongruent. In French, for instance, soleil 'sun' was masculine and lune 'moon' feminine, in stark contrast to Scandinavian where ON sól 'sun' was feminine and máni 'moon' masculine. Like other buffer zones that give up the conflicting category, the East Midlands had little recourse other than to scrap gender.

厳密にいえば,前の記事の説は英語と Norman French の2者の言語接触に関するものであるのに対し,Miller の説は英語と Norman French と Old Norse の3者の言語接触に関するものなので,2つを区別する必要はあるだろう.Miller の仮説を検証するためには,性の消失が最初に "the East Midlands, a BUFFER ZONE" で本格的に始まったことを示す必要がある.また,前の記事でも反論ポイントとして指摘したが,この "BUFFER ZONE" において,どの程度の社会的・個人的な bilingualism あるいは trilingualism が行われていたのかが焦点となる.

だが,いずれにせよ中部以北ではフランス語の関与が認められ得る時代以前にすでに性の消失が進んでいたわけだから,提案されている言語接触は,すでに進行していた性の消失を促したということであり,それを引き起こした原動力だったわけではないことは注意すべきである.この点を押えておきさえすれば,Miller の憶測も一概に否定し去るべきものではないように思われる.

・ Miller, D. Gary. External Influences on English: From its Beginnings to the Renaissance. Oxford: OUP, 2012.

2014-07-23 Wed

■ #1913. 外来要素を英語化した古英語と,本来要素までフランス語化した中英語 [spelling][contact][borrowing][french][hypercorrection][terminology]

「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1]) の記事で,後期古英語のラテン借用語は,英語化した綴字ではなくラテン語のままの綴字で取り込む傾向があることを指摘した.それ以前のラテン借用語は英語化した綴字で受け入れる傾向があったことを考えると,借用の類型論の観点からいえば,後期古英語に向かって substitution の度合いが大きくなったと表現できるのではないか,と.

さて,中英語期に入ると,英語の綴字体系は別の展開を示した.大量のフランス借用語が流入するにつれ,それとともにフランス語式綴字習慣も強い影響を持ち始めた.この英語史上の出来事で興味深いのは,フランス語式綴字習慣に従ったのはフランス借用語のみではなかったことだ.それは勢い余って本来語にまで影響を及ぼし,古英語式の綴字習慣を置き換えていった.主要なものだけを列挙しても,古英語の <c> (= /ʧ/) はフランス語式の <ch> に置換されたし,<cw> は <qw> へ, <s> の一部は <ce> へ,<u> は <ou> へと置換された.ゆえに,本来語でも現代英語において <chin>, <choose>, <queen>, <quick>, <ice>, <mice>, <about>, <house> などと綴るようになっている.これは綴字体系上のノルマン・コンクェストとでもいうべきものであり,この衝撃を目の当たりにすれば,古英語のラテン語式綴字による軽度の substitution など,かわいく見えてくるほどだ.これは,フランス語式綴字習慣が英語に及んだという点で,「#1793. -<ce> の 過剰修正」 ([2014-03-25-1]) で触れたように,一種の過剰修正 (hypercorrection) と呼んでもよいかもしれない(ほかに「#81. once や twice の -ce とは何か」 ([2009-07-18-1]) および「#1153. 名詞 advice,動詞 advise」 ([2012-06-23-1]) も参照).ただし,通常 hypercorrection は単語単位で単発に作用する事例を指すことが多いが,上記の場合には広範に影響の及んでいるのが特徴的である.フランス語式綴字の体系的な substitution といえるだろう.

Horobin (89) が "rather than adjust the spelling of the French loans to fit the native pattern, existing English words were respelled according to the French practices" と述べたとき,それは,中英語がフランス語を英語化しようとしたのではなく,中英語自らがフランス語化しようとしていた著しい特徴を指していたのである.

「#1208. フランス語の英文法への影響を評価する」 ([2012-08-17-1]) や「#1222. フランス語が英語の音素に与えた小さな影響」 ([2012-08-31-1]) で話題にしたように,フランス語の英語への影響は,語彙を除けば,綴字にこそ最も顕著に,そして体系的に現われている.通常,単発の事例に用いられる substitution や hypercorrection という用語を,このような体系的な言語変化に適用すると新たな洞察が得られるのではないかという気がするが,いかがだろうか.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-07-06 Sun

■ #1896. 日本語に入った西洋語 [loan_word][borrowing][japanese][lexicology][borrowing][portuguese][spanish][dutch][italian][russian][german][french]

日本語に西洋語が初めて持ち込まれたのは,16世紀半ばである.「#1879. 日本語におけるローマ字の歴史」 ([2014-06-19-1]) でも触れたように,ポルトガル人の渡来が契機だった.キリスト教用語とともに一般的な用語ももたらされたが,前者は後に禁教となったこともあって定着しなかった.後者では,アルヘイトウ(有平糖)(alfeloa) ,カステラ (Castella),カッパ (capa),カボチャ(南瓜,Cambodia),カルサン(軽袗,calsãn),カルタ (carta),コンペイトウ(金平糖,confeitos),サラサ(更紗,saraça),ザボン (zamboa),シャボン (sabão),ジバン(襦袢,gibão),タバコ(煙草,tabaco),チャルメラ (charamela),トタン (tutanaga),パン (pão),ビイドロ (vidro),ビスカット(ビスケット,biscoito),ビロード (veludo),フラスコ (frasco),ブランコ (blanço),ボオロ (bolo),ボタン (botão) などが残った.16世紀末にはスペイン語も入ってきたが,定着したものはメリヤス (medias) ぐらいだった.

近世中期に蘭学が起こると,オランダ語の借用語が流れ込んでくる.自然科学の語彙が多く,後に軍事関係の語彙も入った.まず,医学・薬学では,エーテル (ether),エキス (extract),オブラート (oblaat),カルシウム (calcium),カンフル (kamfer, kampher),コレラ (cholera),ジギタリス (digitalis),スポイト (spuit),ペスト (pest),メス (mes),モルヒネ (morphine).化学・物理・天文では,アルカリ (alkali),アルコール (alcohol),エレキテル (electriciteit),コンパス (kompas),ソーダ (soda),テレスコープ (telescoop),ピント (brandpunt),レンズ (lenz).生活関係では,オルゴール (orgel),ギヤマン (diamant),コーヒ (koffij),コック (kok),コップ(kop; cf. 「#1027. コップとカップ」 ([2012-02-18-1])),ゴム (gom),シロップ (siroop),スコップ (schop),ズック (doek),ソップ(スープ,soep),チョッキ (jak),ビール (bier),ブリキ (blik),ペン (pen),ペンキ (pek), ポンプ (pomp),ホック (hoek),ホップ (hop),ランプ (lamp).軍事関係では,サーベル (sabel),ピストル (pistool),ランドセル (ransel).

明治時代には西洋語のなかでは英語が優勢となってくるが,明治初期にはいまだ「コップ」「ドクトル」などオランダ借用語の使用が幅を利かせていた.しかし,大正中期以降は英語系が大半を占めるようになり,オランダ風の「ソップ」が英語風の「スープ」へ置換されたように,発音も英語風へと統一されてくる.英語以外の西洋語としては,大正から昭和にかけてドイツ語(主に医学,登山,哲学関係),フランス語(主に芸術,服飾,料理関係),イタリア語(主に音楽関係),ロシア語も見られるようになった.それぞれの例を挙げてみよう.

・ ドイツ語:ノイローゼ(Neurose),カルテ(Karte),ガーゼ(Gaze),カプセル(Kapsel),ワクチン(Vakzin),イデオロギー(Ideologie),ゼミナール(Seminar),テーマ(Thema),テーゼ(These),リュックサック(Rucksack),ザイル(Seil),ヒュッテ(Hütte),オブラート (Oblate), クレオソート (Kreosot).

・ フランス語:デッサン(dessin),コンクール(concours),シャンソン(chanson),ロマン(roman),エスプリ(esprit),ジャンル(genre),アトリエ(atelier),クレヨン(crayon),ルージュ(rouge),ネグリジェ(néglige),オムレツ(omelette),コニャック(cognac),シャンパン(champagne),マヨネーズ(mayonnaise)

・ イタリア語:オペラ(opera),ソナタ(sonata),テンポ(tempo),フィナーレ(finale),マカロニ(macaroni),スパゲッティ(spaghetti)

・ ロシア語:ウォッカ(vodka),カンパ(kampaniya),ペチカ(pechka),ノルマ(norma)

今日,西洋語の8割が英語系であり,借用の対象となる英語の変種としては太平洋戦争をはさんで英から米へと切り替わった.

以上,佐藤 (179--80, 185--86) および加藤他 (74) を参照して執筆した.関連して,「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]),「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1]),「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1]) の記事も参照されたい.

・ 佐藤 武義 編著 『概説 日本語の歴史』 朝倉書店,1995年.

・ 加藤 彰彦,佐治 圭三,森田 良行 編 『日本語概説』 おうふう,1989年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow