2018-05-30 Wed

■ #3320. 英語の諺の分類 [proverb][literature][rhetoric]

英語の諺の分類には,内容によるもの,形式によるもの,起源によるものなどがあるが,The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs の序文に掲げられている内容による3分法を紹介しよう (xi) .

Proverbs fall readily into three main categories. Those of the first type take the form of abstract statements expressing general truths, such as Absence makes the heart grow fonder and Nature abhors a vacuum. Proverbs of the second type, which include many of the more colourful examples, use specific observations from everyday experience to make a point which is general; for instance, You can take a horse to water, but you can't make him drink and Don't put all your eggs in one basket. The third type of proverb comprises sayings from particular areas of traditional wisdom and folklore. In this category are found, for example, the health proverbs After dinner rest a while, after supper walk a mile and Feed a cold and starve a fever. These are frequently classical maxims rendered into the vernacular. In addition, there are traditional country proverbs which relate to husbandry, the seasons, and the weather, such as Red sky at night, shepherd's delight; red sky in the morning, shepherd's warning and When the wind is in the east, 'tis neither good for man nor beast.

分類が微妙なケースはあるだろうが,例えば昨日の記事 ([2018-05-29-1]) で紹介した Handsome is as handsome does という諺は,第2のタイプに属するだろうか.

なお,同辞書による諺の定義は,"A proverb is a traditional saying which offers advice or presents a moral in a short and pithy manner." (xi) である.

・ Speake, Jennifer, ed. The Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. 6th ed. Oxford: OUP, 2015.

2017-01-20 Fri

■ #2825. 「トランプ話法」 [discourse_analysis][rhetoric][implicature]

本日,いよいよ Donald John Trump が第45代アメリカ大統領に就任する(cf. 「#2656. 歴代アメリカ大統領と任期の一覧」 ([2016-08-04-1])).

トランプ氏の話す英語については,選挙戦を通じて様々な評価がなされてきた.2日前の1月18日の読売新聞朝刊6面にも「トランプ話法」に関する記事があった.昨年3月の大統領候補者の話法研究によると,トランプ氏の文法は6年生レベルで,ヒラリー・クリントン氏は7年生レベルだったという.最近は plain spoken の英語が有権者に受けるということで,リンカーンやケネディの格調高い演説はすでに過去のものとなったかのようだ.

認知言語学の大家 George Lakoff によると,トランプ大統領のツイッター上の発言を分析すると,誇張やすり替えを効果的に利用しつつ保守層を取り込んでいることが分かるという.論法という側面で言うと,(1) はなから決めつける,(2) 極端な物言い,(3) 論点のすり替え,(4) 観測気球を揚げる,という特徴が見られるという.これらのレトリックはもちろん意図的であり,国民もマスコミもその手に乗ってしまっていると分析する.(1) は,根拠のないことを前提として提示し,話を進める傾向があることを指す.(2) については,直接いわずとも,保守層には理解できる言い方をすることで示唆する,いわゆる implicature の戦略的利用に長けているという.(4) は,世論の反応を見極めるために「メキシコとの国境の壁を作った後にメキシコに弁済させる」などとぶち上げることなどが相当する.

このようなトランプ話法は,リベラル層から見れば馬鹿げたレトリックということになるが,保守層には効果覿面のようだ.

演説,討論,ツイッターでは register も style も異なり,それに応じてレトリックを含む言語戦略が異なってくるのは当然だが,ときにメディアを嫌う姿勢を示しながらも実はおおいに利用してきたトランプ氏の談話分析は,大統領就任以降も,ますます注目されていくことになるかもしれない.

少々前のことになるが,2013年2月12日の The Guardian より,アメリカ大統領のスピーチレベルの変化に関して,The state of our union is . . . dumber: How the linguistic standard of the presidential address has declined のデータも参照.

2017-01-12 Thu

■ #2817. 名詞構文と形式性 [noun][hypostasis][style][register][rhetoric][discourse_analysis]

ヒトラーが演説の天才だったことはよく知られている.陰でオペラ歌手による発声法の指導まで受けていたというから,完全に演説の政治的価値を見て取っていたことがわかる.ヒトラーの演説を,その政治家としてのキャリアの各段階について,言語学的およびパラ言語学的に分析した著書に,高田著『ヒトラー演説』がある.言語学的分析に関しては,ヒトラー演説150万語からなる自作コーパスを用いた語彙調査が基本となっており,各時代について興味深い分析結果が示されている.

とりわけ私が関心をもったのは,ナチ政権期前半に特徴的に見られる名詞 Ausdruck (表現),Bekenntnis (公言),Verständnis (理解)と関連した名詞構文の多用に関する分析である(高田,p. 161--62).いずれも動詞から派生した名詞であり,「名詞的文体(名詞構文)」に貢献しているという.名詞構文とは,「列車が恐ろしく遅れたこと」を「列車の恐ろしい遅延」と名詞を中心として表現するもので,英語でいえば (the fact) that the train was terribly delayed と the terrible delay of the train の違いである.

思いつくところで名詞構文の特徴を挙げれば,(1) 密度が濃い(あるいはコンパクト),(2) 形式的で書き言葉らしい性格が付される,(3) 実体化 (hypostasis) の作用により意味内容が事実として前提されやすい,ということがある(「#1300. hypostasis」 ([2012-11-17-1]) も参照).これは,ドイツ語,英語,日本語などにも共通する特徴と思われる.

名詞構文においては,対応する動詞構文ではたいてい明示される人称,時制,相,態,法などの文法範疇が標示されないことが多く,その分情報量が少ない.ということは,細かいニュアンスが捨象されたり曖昧のままに置かれるということだが,形式としては高密度でコンパクト,かつ格式張った響きを有するので,内容と形式の間に不安定なギャップが生まれる.外見はしっかりしていそうで中身は曖昧,というつかみ所のないカプセルと化す.それを使用者は「悪用」することができるというわけだ.政治家や役人が名詞構文をレトリックとして好んで使う所以である.

高田の分析によれば,ヒトラーの場合には「このような形式性,書きことばらしさは,ナチ政権期前半においてさまざまな国家的行事における演説に荘厳な印象を与えるためのものであった」 (161--63) という.

・ 高田 博行 『ヒトラー演説』 中央公論新社〈中公新書〉,2014年.

2016-12-11 Sun

■ #2785. The Owl and the Nightingale にみる文と武 [conceptual_metaphor][rhetoric][owl_and_nightingale]

初期中英語で書かれた,梟とナイチンゲールの2者による論争詩 The Owl and the Nightingale を Cartlidge 版で読み進めている.2者は,それぞれの人生観を言葉で議論し合っているのであり,肉体的に争っているわけではない.しかし,議論に関する表現には,肉体的な戦闘に用いられる語句がしばしば流用されており,そのような語句だけをピックアップすると,さながら果たし合いのバトルが繰り広げられているかのようだ.テキストを読んでいると,これぞ概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) としてよく知られた "ARGUMENT IS WAR" そのもの,というふうに見える(「#2548. 概念メタファー」 ([2016-04-18-1]) を参照).

テキストには,文(言葉)と武(武器)による戦いの描写が,ある意味では比喩的に,ある意味では対比的に用いられている箇所がしばしば見られるが,とりわけ ll. 1067--74 の箇所がレトリック的にすぐれていると思う.ナイチンゲールが梟の言いぐさに腹を立て,まさに反論しようとしている箇所の記述である.以下に引用しよう.

Þe Niȝtingale at þisse worde

Mid sworde an mid speres orde,

Ȝif ho mon were, wolde fiȝte:

Ac þo ho bet do ne miȝte

Ho uaȝt mid hire wise tunge.

"Wel fiȝt þat wel specþ," seiþ in þe songe:

Of hire tunge ho nom red.

"Wel fiȝt þat wel specþ," seide Alured.

Cartlidge の現代英語訳(意訳)も引用しておこう.

At these words the Nightingale would have fought with sword and spearpoint had she been a man: but, since she couldn't do any better, she fought with her wise tongue instead. "To fight well, speak well," as the song goes: and so she looked to her tongue for a strategy. "To fight well, speak well," that's what Alfred said.

味読すべき部分は少なくない.

・ l. 1067 worde と l. 1068 orde の脚韻.文と武の対比がよく出ている.ただし,両語の母音は,厳密には同一ではない可能性もある(「#2740. word のたどった音変化」 ([2016-10-27-1]) を参照).

・ l. 1070 wolde と l. 1071 ne miȝte の対比.「したい」のに「できない」もどかしさ.

・ l. 1071 tunge と l. 1072 songe の脚韻.「文」の側に属する縁語(さらに l. 1073 tunge も合わせて).ただし,ここでも,同一母音で押韻するのかどうか,疑惑あり.

・ 全体が,文武両道の名君 Alured の格言として引用されているのもまた一興.

l. 1070 や l. 1072 の韻律も規則的ではなく完璧とはいえないかもしれないが,この箇所は The Owl and the Nightingale における "ARGUMENT IS WAR" を味わうには最良の箇所と思ったので,メモしておいた.

ちなみに,この箇所に付されている注によれば,ここは皮肉とも読めるという.これまた,おもしろい.

It is incongruous to imagine the Nightingale wielding such implements . . . and ironic that the narrator here implicitly associates reason with the animals and unrestrained violence with people.

・ Cartlidge, Neil, ed. The Owl and the Nightingale. Exeter: U of Exeter P, 2001.

2016-09-08 Thu

■ #2691. 英語の諺の受容の歴史 [literature][proverb][rhetoric]

Simpson の英語諺辞典のイントロ (x) に,その受容の歴史が概説されていた.簡潔にまとまっているので,以下に引用する.

It is sometimes said that the proverb is going out of fashion, or that it has degenerated into the cliché. Such views overlook the fact that while the role of the proverb in English literature has changed, its popular currency has remained constant. In medieval times, and even as late as the seventeenth century, proverbs often had the status of universal truths and were used to confirm or refute an argument. Lengthy lists of proverbs were compiled to assist the scholar in debate; and many sayings from Latin, Greek, and the continental languages were drafted into English for this purpose. By the eighteenth century, however, the popularity of the proverb had declined in the work of educated writers, who began to ridicule it as a vehicle for trite, conventional wisdom. In Richardson's Clarissa Harlowe (1748), the hero, Robert Lovelace, is congratulated on his approaching marriage and advised to men his foolish ways. His uncle writes: 'It is a long lane that has no turning.---Do not despise me for my proverbs.' Swift, in the introduction to his Polite Conversation (1738), remarks: 'The Reader must learn by all means to distinguish between Proverbs, and those polite Speeches which beautify Conversation: . . As to the former, I utterly reject them out of all ingenious Discourse.' It is easy to see how proverbs came into disrepute. Seemingly contradictory proverbs can be paired---Too many cooks spoil the broth with Many hands make light work: Absence makes the heart grow fonder with its opposite Out of sight, out of mind. Proverbs could thus become an easy butt for satire in learned circles, and are still sometimes frowned upon by the polished stylist. The proverb has none the less retained its popularity as a homely commentary on life and as a reminder that the wisdom of our ancestors may still be useful to use today.

中世から初期近代までは,諺は議論などでも用いられる賢き知恵として尊ばれていた.実際,16--17世紀には,諺は文学や雄弁術の華だった.John Heywood (1497?--1580?) が1546年に諺で戯曲を著わし,Michael Drayton (1563--1631) がソネットを書き,16世紀の下院では諺による演説もなされたほどだ.ところが,18世紀以降,諺は知識人の間で使い古された表現として軽蔑されるようになった.とはいえ,一般民衆の間では諺は生活の知恵として連綿と口にされてきたのであり,諺文化が廃れたわけではない.諺が用いられる register こそ変化してきたが,諺そのものが衰えたわけではないのである.

なお,最古の英語諺集は,宗教的,道徳的な教訓を納めた,いわゆる "Proverbs of Alfred" (c. 1150--80) である.初学者にラテン語を教える修道院,修辞学の学校,説教などで言及されることにより,諺は広められ,写本にも保存されるようになった.

・ Simpson, J. A., ed. The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Proverbs. Oxford: OUP, 1892.

・ Encyclopaedia Britannica. Encyclopaedia Britannica 2008 Ultimate Reference Suite. Chicago: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2008.

2016-07-29 Fri

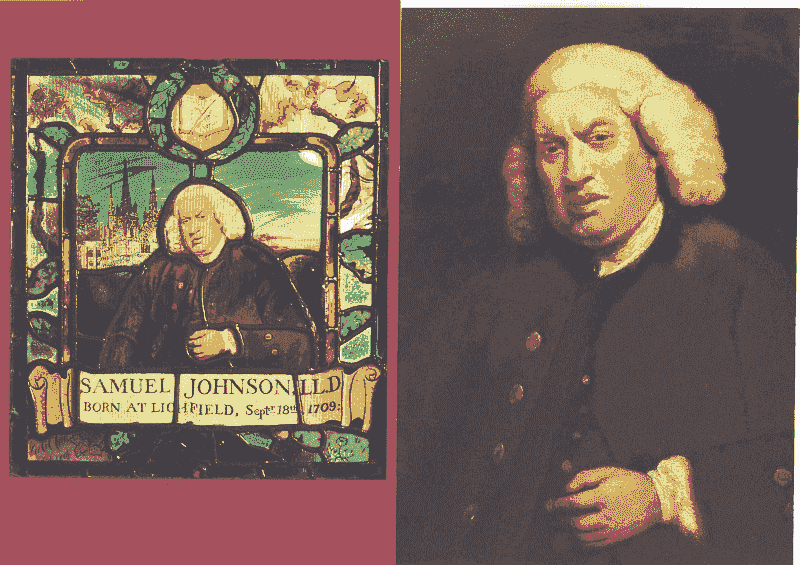

■ #2650. 17世紀末の質素好みから18世紀半ばの華美好みへ [rhetoric][style][johnson]

文学史・文体論史では,17世紀終わりから18世紀終わりの Augustan Period において,特にその前半は,質素な文体が好まれたといわれる.しかし,18世紀前半から,地味な文体に飽き足りず,少しずつ派手好みの文体に挑戦する文筆家が現われていた.ラテン語の華美な魅力に耐えられず,派手さを喧伝する書き手が現われたのだ.その新しい方針を採った文豪の1人が Samuels Johnson である.彼こそが18世紀半ばの華美好みの書き手の代表者となったということから,この文体の潮流の変化は "Johnson's Latinate Revival" ともいわれる.

18世紀中に文体や使用する語種に変化があったことは,明らかである.Knowles (137) によれば,

The typical prose style of the period following the Restoration of the monarchy . . . was essentially unadorned. This plainness of style was a reaction to the taste of the preceding period. Early in the eighteenth century taste began to change again, and there are suggestions that ordinary language is not really sufficient for high literature. Addison in the Spectator (no. 285) argues: 'many an elegant phrase becomes improper for a poet or an orator, when it has been debased by common use.' By the middle of the century, Lord Chesterfield argues for a style raised from the ordinary; in a letter to his son he writes: 'Style is the dress of thoughts, and let them be ever so just, if your style is homely, coarse, and vulgar, they will appear to as much disadvantage, and be as ill-received as your person, though ever so well proportioned, would, if dressed in rags, dirt and tatters.' At this time, Johnson's dictionary appeared, followed by Lowth's grammar and Sheridan's lectures on elocution. By the 1760s, at the beginning of the reign of George III, the elevated style was back in fashion.

The new style is associated among others with Samuel Johnson. Johnson echoes Addison and Chesterfield: 'Language is the dress of thought . . . and the most splendid ideas drop their magnificence, if they are conveyed by words used commonly upon low and trivial occasions, debased by vulgar mouths, and contaminated by inelegant applications' . . . . This gives rise to the belief that the language of important texts must be elevated above normal language use. Whereas in the medieval period Latin was used as the language of record, in the late eighteenth century Latinate English was used for much the same purpose.

ここで述べられているように,Augustan Period の前半は社会は保守的であり,その余波は言語的にも明らかである.例えば,OED でも他の時代に比べて新語があまり現われていない(cf. 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]),「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1])).しかし,Augustan periods の後半,18世紀後半には前時代からの反動で,Johnson に代表される華美な語法が流行となるに至る.その2世紀前に "aureate diction" (cf. 「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1])) があったのと同様に,もう1度同種の流行がはびこったのである.

文体や語彙借用に関する限り,英語史においてこの繰り返しは何度となく起こっている.これは,例えば日本における漢字を重視する傾向のリバイバルなどと似たような事情でなないだろうか.

・ Knowles, Gerry. A Cultural History of the English Language. London: Arnold, 1997.

2016-07-11 Mon

■ #2632. metaphor と metonymy (2) [metaphor][metonymy][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics]

metaphor と metonymy について,「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]),「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1]),「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]),「#2496. metaphor と metonymy」 ([2016-02-26-1]) で話題にしてきた.今回も,両者の関係について考えてみたい.

次の2つの文を考えよう.

(1) Metonymy: San Francisco is a half hour from Berkeley.

(2) Metaphor: Chanukah is close to Christmas.

(1) の a half hour は,時間的な隔たりを意味していながら,同時にその時間に相当する空間上の距離を表わしている.30分間の旅で進むことのできる距離を表わしているという点で,因果関係の隣接性を利用したメトニミーといえるだろう.一見すると時間と空間の2つのドメインが関わっているようにみえるが,旅という1つのドメインのなかに包摂されると考えられる.この文の主題は,時間と空間の関係そのものである.

一方,(2) の close to は,時間的に間近であることが,空間的な近さに喩えられている.ここでは時間と空間という異なる2つのドメインが関与しており,メタファーが利用されている.この文の主題は,あくまで時間である.空間は,主題である時間について語る手段にすぎない.

Lakoff and Johnson (266--67) は,この2つの文について考察し,メタファーとメトニミーの特徴の差を的確に説明している.

When distinguishing metaphor and metonymy, one must not look only at the meanings of a single linguistic expression and whether there are two domains involved. Instead, one must determine how the expression is used. Do the two domains from a single, complex subject matter in use with a single mapping? If so, you have metonymy. Or, can the domains be separate in use, with a number of mappings and with one of the domains forming the subject matter (the target domain), while the other domain (the source) is the basis of significant inference and a number of linguistic expressions? If this is the case, then you have metaphor.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-06-25 Sat

■ #2616. 政治的な意味合いをもちうる概念メタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

「#2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー」 ([2016-06-02-1]) で示唆したように,認知言語学的な見方によれば,概念メタファー (conceptual_metaphor) は思考に影響を及ぼすだけでなく,行動の基盤ともなる.すなわち,概念メタファーは,人々に特定の行動を促す原動力となりうるという点で,政治的に利用されることがあるということだ.

Lakoff and Johnson の古典的著作 Metaphors We Live By の最終章の最終節に,"Politics" と題する文章が置かれているのは示唆的である.政治ではしばしば「人間性を奪うような」 (dehumanizing) メタファーが用いられ,それによって実際に「人間性の堕落」 (human degradation) が生まれていると,著者らは指摘する.同著の最後の2段落を抜き出そう.

Political and economic ideologies are framed in metaphorical terms. Like all other metaphors, political and economic metaphors can hide aspects of reality. But in the area of politics and economics, metaphors matter more, because they constrain our lives. A metaphor in a political or economic system, by virtue of what it hides, can lead to human degradation.

Consider just one example: LABOR IS A RESOURCE. Most contemporary economic theories, whether capitalist or socialist, treat labor as a natural resource or commodity, on a par with raw materials, and speak in the same terms of its cost and supply. What is hidden by the metaphor is the nature of the labor. No distinction is made between meaningful labor and dehumanizing labor. For all of the labor statistics, there is none on meaningful labor. When we accept the LABOR IS A RESOURCE metaphor and assume that the cost of resources defined in this way should be kept down, then cheap labor becomes a good thing, on a par with cheap oil. The exploitation of human beings through this metaphor is most obvious in countries that boast of "a virtually inexhaustible supply of cheap labor"---a neutral-sounding economic statement that hides the reality of human degradation. But virtually all major industrialized nations, whether capitalist or socialist, use the same metaphor in their economic theories and policies. The blind acceptance of the metaphor can hide degrading realities, whether meaningless blue-collar and white-collar industrial jobs in "advanced" societies or virtual slavery around the world.

"LABOUR IS A RESOURCE" という概念メタファーにどっぷり浸かった社会に生き,どっぷり浸かった生活を送っている個人として,この議論には反省させられるばかりである.一方で,(反省しようと決意した上で)実際に反省することができるということは,当該の概念メタファーによって,人間の思考や行動が完全に拘束されるわけではないということにもなる.概念メタファーと思考・行動の関係に関する議論は,サピア=ウォーフの仮説 (sapir-whorf_hypothesis) を巡る議論とも接点が多い.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-06-02 Thu

■ #2593. 言語,思考,現実,文化をつなぐものとしてのメタファー [metaphor][cognitive_linguistics][sapir-whorf_hypothesis][rhetoric][conceptual_metaphor]

Lakoff and Johnson は,メタファー (metaphor) を,単に言語上の技巧としてではなく,人間の認識,思考,行動の基本にあって現実を把握する方法を与えてくれるものととしてとらえている.今や古典と呼ぶべき Metaphors We Live By では一貫してその趣旨で主張がなされているが,そのなかでもとりわけ主張の力強い箇所として,"New Meaning" と題する章の末尾より以下の文章をあげよう (145--46) .

Many of our activities (arguing, solving problems, budgeting time, etc.) are metaphorical in nature. The metaphorical concepts that characterize those activities structure our present reality. New metaphors have the power to create a new reality. This can begin to happen when we start to comprehend our experience in terms of a metaphor, and it becomes a deeper reality when we begin to act in terms of it. If a new metaphor enters the conceptual system that we base our actions on, it will alter that conceptual system and the perceptions and actions that the system gives rise to. Much of cultural change arises from the introduction of new metaphorical concepts and the loss of old ones. For example, the Westernization of cultures throughout the world is partly a matter of introducing the TIME IS MONEY metaphor into those cultures.

The idea that metaphors can create realities goes against most traditional views of metaphor. The reason is that metaphor has traditionally been viewed as a matter of mere language rather than primarily as a means of structuring our conceptual system and the kinds of everyday activities we perform. It is reasonable enough to assume that words alone don't change reality. But changes in our conceptual system do change what is real for us and affect how we perceive the world and act upon those perceptions.

The idea that metaphor is just a matter of language and can at best only describe reality stems from the view that what is real is wholly external to, and independent of, how human beings conceptualize the world---as if the study of reality were just the study of the physical world. Such a view of reality---so-called objective reality---leaves out human aspects of reality, in particular the real perceptions, conceptualizations, motivations, and actions that constitute most of what we experience. But the human aspects of reality are most of what matters to us, and these vary from culture to culture, since different cultures have different conceptual systems. Cultures also exist within physical environments, some of them radically different---jungles, deserts, islands, tundra, mountains, cities, etc. In each case there is a physical environment that we interact with, more or less successfully. The conceptual systems of various cultures partly depend on the physical environments they have developed in.

Each culture must provide a more or less successful way of dealing with its environment, both adapting to it and changing it. Moreover, each culture must define a social reality within which people have roles that make sense to them and in terms of which they can function socially. Not surprisingly, the social reality defined by a culture affects its conception of physical reality. What is real for an individual as a member of a culture is a product both of his social reality and of the way in which that shapes his experience of the physical world. Since much of our social reality is understood in metaphorical terms, and since our conception of the physical world is partly metaphorical, metaphor plays a very significant role in determining what is real for us.

この引用中には,本書で繰り返し唱えられている主張がよく要約されている.概念メタファーは,認知,行動,生活の仕方を方向づけるものとして,個人の中に,そして社会の中に深く根を張っており,それ自身は個人や社会の経験的基盤の上に成立している.言語表現はそのような盤石な基礎の上に発するものであり,ある意味では皮相的とすらいえる.メタファーとは,言語上の技巧ではなく,むしろその基盤のさらに基盤となるくらい認知過程の深いところに埋め込まれているものである.

Lakoff and Johnson にとっては,言語を研究しようと思うのであれば,人間の認知過程そのものから始めなければならないということだろう.この前提が,認知言語学の出発点といえる.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-05-09 Mon

■ #2569. dead metaphor (2) [metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics][terminology]

昨日の記事 ([2016-05-08-1]) に引き続き,dead metaphor について.dead metaphor とは,かつては metaphor だったものが,やがて使い古されて比喩力・暗示力を失ってしまった表現を指すものであると説明した.しかし,メタファーと認知の密接な関係を論じた Lakoff and Johnson (55) は,dead metaphor をもう少し広い枠組みのなかでとらえている.the foot of the mountain の例を引きながら,なぜこの表現が "dead" metaphor なのかを丁寧に説明している.

Examples like the foot of the mountain are idiosyncratic, unsystematic, and isolated. They do not interact with other metaphors, play no particularly interesting role in our conceptual system, and hence are not metaphors that we live by. . . . If any metaphorical expressions deserve to be called "dead," it is these, though they do have a bare spark of life, in that they are understood partly in terms of marginal metaphorical concepts like A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON.

It is important to distinguish these isolated and unsystematic cases from the systematic metaphorical expressions we have been discussing. Expressions like wasting time, attacking positions, going our separate ways, etc., are reflections of systematic metaphorical concepts that structure our actions and thoughts. They are "alive" in the most fundamental sense: they are metaphors we live by. The fact that they are conventionally fixed within the lexicon of English makes them no less alive.

「死んでいる」のは,the foot of the mountain という句のメタファーや,そのなかの foot という語義におけるメタファーにとどまらない.むしろ,表現の背後にある "A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON" という概念メタファー (conceptual metaphor) そのものが「死んでいる」のであり,だからこそ,これを拡張して *the shoulder of the mountain や *the head of the mountain などとは一般的に言えないのだ.Metaphors We Live By という題の本を著わし,比喩が生きているか死んでいるか,話者の認識において活性化されているか否かを追究した Lakoff and Johnson にとって,the foot of the mountain が「死んでいる」というのは,共時的にこの表現のなかに比喩性が感じられないという局所的な事実を指しているのではなく,話者の認知や行動の基盤として "A MOUNTAIN IS A PERSON" という概念メタファーがほとんど機能していないことを指しているのである.引用の最後で述べられている通り,表現が慣習的に固定化しているかどうか,つまり常套句であるかどうかは,必ずしもそれが「死んでいる」ことを意味しないという点を理解しておくことは重要である.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-05-08 Sun

■ #2568. dead metaphor (1) [metaphor][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics][terminology][semantics][semantic_change][etymology]

metaphor として始まったが,後に使い古されて常套語句となり,もはや metaphor として感じられなくなったような表現は,"dead metaphor" (死んだメタファー)と呼ばれる.「机の脚」や「台風の目」というときの「脚」や「目」は,本来の人間(あるいは動物)の体の部位を指すものからの転用であるという感覚は希薄である.共時的には,本来的な語義からほぼ独立した別の語義として理解されていると思われる.英語の the legs of a table や the foot of the mountain も同様だ.かつては生き生きとした metaphor として機能していたものが,時とともに衰退 (fading) あるいは脱メタファー化 (demetaphorization) を経て,化石化したものといえる(前田,p. 127).

しかし,上のメタファーの例は完全に「死んでいる」わけではない.後付けかもしれないが,机の脚と人間の脚とはイメージとして容易につなげることはできるからだ.もっと「死んでいる」例として,pupil の派生語義がある.この語の元来の語義は「生徒,学童」だが,相手の瞳に映る自分の像が小さい子供のように見えるところから転じて「瞳」の語義を得た.しかし,この意味的なつながりは現在では語源学者でない限り,意識にはのぼらず,共時的には別の単語として理解されている.件の比喩は,すでにほぼ「死んでいる」といってよい.

「死んでいる」程度の差はあれ,この種の dead metaphor は言語に満ちている.「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]) で列挙したように,語という単位で考えても,その語源をひもとけば,非常に多数の語の意味が dead metaphor として存在していることがわかる.advert, comprehend など,そこであげた多くのラテン語由来の語は,英語への借用がなされた時点で,すでに共時的に dead metaphor であり,「死んだメタファーの輸入品」(前田,p. 127)と呼ぶべきものである.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

・ 谷口 一美 『学びのエクササイズ 認知言語学』 ひつじ書房,2006年.

2016-02-26 Fri

■ #2496. metaphor と metonymy [metaphor][metonymy][cognitive_linguistics][rhetoric]

標題の2つの修辞的技巧は,近年の認知言語学の進展とともに,2つの認知の方法として扱われるようになってきた.2つはしばしば対比されるが,metaphor は2項の類似性 (similarity) に基づき,metonymy は2項の隣接性 (contiguity) に基づくというのが一般的になされる説明である.しかし,Lakoff and Johnson (36) は,両者の機能的な差異にも注目している.

Metaphor and metonymy are different kinds of processes. Metaphor is principally a way of conceiving of one thing in terms of another, and its primary function is understanding. Metonymy, on the other hand, has primarily a referential function, that is, it allows us to use one entity to stand for another.

なるほど,metaphor にも metonymy にも,理解の仕方にひねりを加えるという機能と,指示対象の仕方を一風変わったものにするという機能の両方があるには違いないが,それぞれのレトリックの主たる機能といえば,metaphor は理解に関係するほうで,metonymy は指示に関係するほうだろう.

metonymy の指示機能について顕著な点は,metonymy を用いない通常の表現による指示と異なり,指示対象のどの側面にとりわけ注目しつつ指示するかという「焦点」の情報が含まれていることである.Lakoff and Johnson (36) が挙げている例を引けば,"The Times hasn't arrived at the press conference yet." において,"The Times" の指示対象は,同名の新聞のことでもなければ,新聞社そのもののことでもなく,新聞社を代表する報道記者である.主語にその報道記者の名前を挙げても,指示対象は変わらず,この文の知的意味は変わらない.しかし,あえて metonymy を用いて "The Times" と表現することによって,指示対象たる報道記者が同新聞社の代表者であり責任者であるということを焦点化しているのである.直接名前を用いてしまえば,この焦点化は得られない.Lakoff and Johnson (37) 曰く,

[Metonymy] allows us to focus more specifically on certain aspects of what is being referred to.

metaphor と metonymy については,「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]),「#2406. metonymy」 ([2015-11-28-1]),「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1980.

2016-01-23 Sat

■ #2462. an angel of a girl (2) [metaphor][rhetoric][word_order][syntax][preposition][reanalysis][syntax]

昨日に続いて標題の表現について,Quirk et al. (1284--85) にこの構文が詳説されている.以下に再現しよう.

A special case of prepositional apposition is offered by singular count nouns where the of-phrase is subjective . . ., eg:

the fool of a policeman

an angel of a girl

this jewel of an island

This structure consisting of determiner + noun (N2) + of + indefinite article + noun (N1) is not a regular prepositional postmodification, since N1 is notionally the head, as can be seen in the paraphrases:

The policeman is a fool. [note the AmE informal variant some fool policeman]

The girl is an angel.

This island is a jewel.

The whole part N2 + of + a corresponds to an adjective:

the foolish policeman

an angelic girl

this jewel-like island

The natural segmentation is reflected in variant spellings, as in the familiar AmE expression a hell of a guy (nonstandard spelling: a helluva guy).

In this construction, the determiner of N1 must be the indefinite article, but there is no such constraint on the determiner of N2:

''a'' ─┐ ┌ ''a policeman'' ''the'' │ ''fool of'' │ *''the policeman'' ''this'' │ └ *''policeman'' ''that'' ─┘

Also, N2 must be singular:

?*those fools of policemen

The possessive determiner actually notionally determines N1, not N2:

her brute of a brother ['Her brother was a brute..']

Both N2 and N1 can be premodified:

a little mothy wisp of a man

this gigantic earthquake of a piece of music

a dreadful ragbag of a British musical

this crescent-shaped jewel of a South Sea island

最後の this crescent-shaped jewel of a South Sea island のように,N1 と N2 の両方が前置修飾されているような例では,この名詞句全体における中心がどこなのかが曖昧である.はたして統語的な主要部と意味的な重心は一致しているのか否か.統語と意味の対応関係を巡る共時理論的な問題は残るにせよ,通時的にみれば,片方の足は元来の構造の上に立ち,もう片方は新しい構造の上に立っているかのようであり,その立場を活かした修辞的表現となっているのがおもしろい.

生成文法としては分析が難しく,認知言語学や修辞学としてはこの上ない興味深い構文である.ここに通時的観点をどのように食い込ませていくか,調査しがいのあるトピックのように思われる.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2016-01-22 Fri

■ #2461. an angel of a girl (1) [metaphor][rhetoric][word_order][syntax][preposition][reanalysis][syntax]

前置詞 of の用法の1つとして,標題のような例がある.an angel of a girl は意味的に "a girl like an angel" とパラフレーズされ,直喩に相当する表現となる.なぜこのような意味が生じるのだろうか.

ここでの of の用法は広い意味で「同格」 (apposition) といってよい.OED によると,of の語義23に "Between two nouns which are in virtual apposition" とあり,その語義の下に細分化された23bにおいてこの用法が扱われている.

b. In the form of, in the guise of.

The leading noun is the latter, to which the preceding noun with of stands as a qualification, equivalent to an adjective; thus 'that fool of a man' = that foolish man, that man who deserves to be called 'fool'; 'that beast of a place' = that beastly place.

Quot. ?c1200 is placed here by Middle Eng. Dict.; however the of-phrase seems to complement the verb and its object . . . rather than the preceding noun only as in later examples.

[?c1200 Ormulum (Burchfield transcript) l. 11695 Þeȝȝ hallȝhenn cristess flæsh off bræd & cristess blod teȝȝ hallȝenn. Off win.

a1375 William of Palerne (1867) 226 (MED), So fair a siȝt of seg ne sawe he neuer are.

. . . .

1992 Vanity Fair (N.Y.) Feb. 144/3 The Schramsberg offers a whirlwind of a mousse, tasting of lemon and yeast.

MED から取られている例があるので,MED の of (prep.) を参照してみると,同様に "quasi-appositional relationship" 表わす用法として語義19b(b)に "in the form of (sth. or sb.)" とみえる.解釈の分かれる例文もありそうだが,15世紀半ばからの "a faire body of a woman" という明らかな該当例をみると,遅くとも後期中英語には同用法が発達していたことは確かである.

"a faire body of a woman" は元来「ある女性の(姿をした)美しき体」であり,主要部は of の前位置に立つ body のはずだった.ところが,使われ続けるうちに,body of a の塊が全体として後続の名詞 woman を修飾するように感じられるようになってきたのだろう.標題の an angel of a girl でいえば,これは元来「少女の(姿をした)天使」を意味する表現だったと思われるが,angel of a の塊が全体として形容詞 angelic ほどの機能を獲得して,後続の girl にかかっていくものとして統語的に再分析 (reanalysis) された.

一般的にいえば,a [X] of a [Y] の構造において,本来的には [X] が主要部だったが,再分析を経て [Y] が主要部となり,"a [X]-like Y" ほどを意味するようになったものと理解できる.この本来的な構造は,OED では以下のように語義23aにおいて扱われており,現在までに廃義となっている.

†a. In the person of; in respect of being; to be; for. Obs.

The leading noun is the former, of the qualification of which the phrase introduced by of constitutes a limitation; thus 'he was the greatest traveller of a prince', i.e. the greatest traveller in the person of a prince, or so far as princes are concerned. The sense often merges with that of the partitive genitive. . . . .

c1275 (?a1200) Laȝamon Brut (Calig.) (1963) 3434 Þe hǣhste eorles..curen heom enne king of ane cnihte þe wes kene.

c1300 (?a1200) Laȝamon Brut (Otho) 4980 Hadden hii anne heuedling of on heȝe ibore man.

a1470 Malory Morte Darthur (Winch. Coll.) 119 He was a ryght good knyght of a yonge man.

1697 K. Chetwood Life Virgil in Dryden tr. Virgil Wks. sig. *4v, Cæsar..the greatest Traveller, of a Prince, that had ever been.

1748 Ld. Chesterfield Let. 20 Dec. (1932) (modernized text) IV. 1278 Allowed to be the best scholar of a gentleman in England.

しかし,再分析前の23aと後の23bの用法を,文脈から明確に区別することは難しいように思われる.修辞的な観点からみれば,この統語的な両義性こそが新たな認識を生み出しているようにも思われる.結果として,同時に形容詞修飾風でもあり直喩でもあり隠喩でもある不思議な表現が,ここに生まれている.便宜的に an angelic girl とはパラフレーズできるものの,an angel of a girl の与える修辞的効果は大きく異なる.

類似した統語的再分析の例,主要部の切り替わりの例については,「#2333. a lot of」 ([2015-09-16-1]) と「#2343. 19世紀における a lot of の爆発」 ([2015-09-26-1]) を参照.

2015-11-28 Sat

■ #2406. metonymy [metonymy][metaphor][terminology][semantics][semantic_change][rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics]

「#2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである」 ([2015-04-23-1]) でメタファー (metaphor) について解説した.対するメトニミー (metonymy) については,各所で触れながらも,解説する機会がなかったので,Luján (291--92) などに拠りながらここで紹介したい.

伝統的な修辞学の世界では「換喩」として知られてきたが,近年の認知言語学や意味論では横文字のまま「メトニミー」と呼ばれることが多い.この用語は,ギリシア語の metōnimía (change of name) に遡る.教科書的な説明を施せば,メタファーが2項の類似性 (similarity) に基づくのに対して,メトニミーは2項の隣接性 (contiguity) に基づくとされる.メタファーでは,2項はそれぞれ異なるドメイン (domain) に属しているが,何らかの類似性によって両者が結ばれる.メトニミーでは,2項は同一のドメインに属しており,その内部で何らかの隣接性によって両者が結ばれる.類似性と隣接性が厳密に区別できるものかという根本的な疑問もあるものの,当面はこの理解でよい (cf. 「#2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居」 ([2015-05-02-1])) .

メトニミーの本質をなす隣接性には,様々な種類がある.部分と全体(特に 提喩 (synecdoche) と呼ばれる),容器と内容,材料と物品,時間と出来事,場所とそこにある事物,原因と結果など,何らかの有機的な関係があれば,すべてメトニミーの種となる.したがって,意味の変異や変化において,きわめて卑近な過程である.「やかんが沸いている」というときの「やかん」は本来は容器だが,その容器の中に含まれる「水」を意味する.glass は本来「ガラス」という材料を指すが,その材料でできた製品である「グラス」をも意味する.ラテン語 sexta (sixth (hour)) はある時間を表わしていたが,そのスペイン語の発展形 siesta はその時間にとる午睡を意味するようになった.「永田町」や Capitol Hill は本来は場所の名前だが,それぞれ「首相官邸」と「米国議会」を意味する.「袖を濡らす」という事態は泣くという行為の結果であることから,「泣く」を意味するようになった.count one's beads という句において,元来 beads は「祈り」を意味したが,祈りの回数を数えるのにロザリオの数珠玉をもってしたことから,beads が「数珠玉」そのものを意味するようになった.隣接性は,物理法則に基づく因果関係から文化・歴史に強く依存する故事来歴に至るまで,何らかの有機的な関係があれば成立しうるという点で,応用範囲が広い.

Saeed (365--66) より,英語からの典型的な例を種類別に挙げよう.

・ PART FOR WHOLE (synecdoche): All hands on deck.

・ WHOLE FOR PART (synecdoche): Brazil won the world cup.

・ CONTAINER FOR CONTENT: I don't drink more than two bottles.

・ MATERIAL FOR OBJECT: She needs a glass.

・ PRODUCER FOR PRODUCT: I'll buy you that Rembrandt.

・ PLACE FOR INSTITUTION: Downing Street has made no comment.

・ INSTITUTION FOR PEOPLE: The Senate isn't happy with this bill.

・ PLACE FOR EVENT: Hiroshima changed our view of war.

・ CONTROLLED FOR CONTROLLER: All the hospitals are on strike.

・ CAUSE FOR EFFECT: His native tongue is Hausa.

・ Luján, Eugenio R. "Semantic Change." Chapter 16 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum International, 2010. 286--310.

・ Saeed, John I. Semantics. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

2015-06-29 Mon

■ #2254. 意味変化研究の歴史 [history_of_linguistics][semantic_change][semantic][rhetoric][causation][cognitive_linguistics]

連日,Waldron に依拠して意味変化の記事を書いてきたが,同じ Waldron (115--16) を参照して,19世紀以降の意味変化研究史を振り返ってみたい.

近代的な意味変化論は,19世紀初頭のドイツに起こった.比較言語学が出現し,音韻変化が研究され始めたのと同じ頃,言語学者は古典的なレトリックの用語により意味変化を記述できる可能性に気づいた.共時的な言葉のあや (figures of speech) と通時的な意味変化の類縁性に気がついたのである.例えば,意味変化の分類が,synecdoche, metonymy, metaphor などのレトリック用語に基づいてなされるなどした.意味変化研究史の幕開けがまさにこの関係の気づきにあったことを考えると,昨今,古典的レトリックと意味変化の関係が認知言語学の立場から再び注目を集めている状況は,非常に興味深い (cf. 「#2191. レトリックのまとめ」 ([2015-04-27-1])) .

レトリック用語による意味変化の分類から始まり,19世紀中には論理的な分類も発達した.ある意味で現代にまで根強く続いている Extension, Restriction, Transfer の3分法である.これをより論理的に整理したのが,1894年の R. Thomas による分類で,以下のように図示できる (Waldron 115) .

I Change within the same conceptual sphere

(a) Species pro genere

(b) Genus pro specie

II Change through transfer to another conceptual sphere

(a) Through subjective correspondence (metaphor)

(b) Through objective correspondence (metonymy)

20世紀に入ると,これまでのような意味変化の分類よりも,意味変化の原因(心理的,社会的,言語的)へと関心が移った.意味変化研究に社会や歴史の観点が取り入れられるようになり,科学技術の発展,社会道徳の変化,各種レジスターなどが意味変化に及ぼしてきた影響が論じられるようになった.

意味変化に関する20世紀の代表的著作として Stern, Ullmann, Waldron が挙げられるが,意味変化の分類や原因を巡る議論は,およそ出尽くし,整理されたといえるかもしれない.近年は,上記のような古典的な意味変化論から脱却して,認知言語学,文法化研究,語用論などから示唆を得た,新しい意味変化研究が生まれてきつつある.

意味論全体の研究史については,「#1686. 言語学的意味論の略史」 ([2013-12-08-1]) を参照.

・ Waldron, R. A. Sense and Sense Development. New York: OUP, 1967.

2015-05-02 Sat

■ #2196. マグリットの絵画における metaphor と metonymy の同居 [semiotics][metaphor][metonymy][semantics][rhetoric]

先日,国立新美術館で開催されているマグリット展に足を運んだ.13年ぶりの大回顧展という.

René Magritte (1898--1967)はベルギーの国民的画家で,後のアートやデザインにも大きな影響を与えたシュルレアリスムの巨匠である.言葉とイメージの問題,あるいは記号論の問題にこだわり続けたという点で,マグリットの絵画は「言語学的に」鑑賞することが可能である.

マグリットは metaphor と metonymy を意識的に多用した.多用したというよりは,それを生涯のテーマとして掲げていた.metaphor や metonymy という言葉のあやを絵画の世界に持ち込み,目に見える形で描いた.つまり,目に見える詩の芸術家である.

意味論において metaphor は類似性 (similarity) に基づき,metonymy は隣接性 (contiguity) に基づくとされ,2つは対置されることが多い.しかし,対置される関係ではないという議論もしばしば聞かれる.マグリットも,絵画のなかで metaphor と metonymy を対立させるというよりは,しばしば同居させ,融合させることによって,この議論に参加しているかのようである.

例えば,マグリットの絵には,一本の木が,立てられた一枚の葉の輪郭として描かれているものが何点もある.木と葉の関係は全体と部分の関係であり,典型的な metonymy の例だが,同時に両者の輪郭が類似しているという点において,その絵は metaphor ともなっている.絵を眺めていると,metonymy でもあり metaphor でもあるという不思議な感覚が生じてくるのだ.もう1つ例を挙げると,Le Viol (陵辱)という作品では,女性の胸像がそのまま女性の顔とも見えるように描かれている.体と顔とは上下に互いに隣接しており metonymy の関係をなすが,その絵においてはいずれとも見ることができるという点で metaphor でもある.Dubnick (417) によれば,マグリットは,この絵のなかで視覚的に metaphor と metonymy を表現したのみならず,同時に背後で言葉遊びもしているという.

Le Viol (The Rape, 1934) which substitutes a woman's torso for her face, is predominantly metonymic though relationships of similarity are also important. The breasts are substituted for eyes, the navel for the nose, and perhaps a risqué pun on the word labia is intended. This monstrous image is both funny and grotesque. But even though this image may convey a metaphorical and moral message about the sexual basis of a woman's identity, especially in the eyes of the rapist, the core of the painting is really the vulgar synecdoche which replaces the word "woman" with a slang term for a female's genitals. Thus, this is both a verbal and a visual pun.

Dubnick (418) は,言語学者 Roman Jakobson を引き合いに出しながら,マグリットを次のように評価して評論を締めくくっている.

Jakobson's linguistic theories about metaphor and metonymy suggest that the phrase "visible poetry" was not an empty metaphor for Magritte, who created figures of speech with paint.

・ Dubnick, Randa. "Visible Poetry: Metaphor and Metonymy in the Paintings of René Magritte." Contemporary Literature 21.3 (1980): 407--19.

2015-04-27 Mon

■ #2191. レトリックのまとめ [rhetoric][cognitive_linguistics][oxymoron]

レトリックは,古典的には (1) 発想,(2) 配置,(3) 修辞(文体),(4) 記憶,(5) 発表の5部門に分けられてきた.狭義のレトリックは (3) の修辞(文体)を指し,そこでは様々な技法が命名され,分類されてきた.近年,古典的レトリックは認知言語学の視点から見直されてきており,単なる技術を超えて,人間の認識を反映するもの,言語の機能について再考させるものとして注目を浴びてきている.

瀬戸の読みやすい『日本語のレトリック』では,数ある修辞的技法を30個に限定して丁寧な解説が加えられている.技法の名称,別名(英語名),説明,具体例について,瀬戸 (200--05) の「レトリック三〇早見表」を以下に再現したい.

| 名称 | 別名 | 説明 | 例 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 隠喩 | 暗喩,メタファー (metaphor) | 類似性にもとづく比喩である.「人生」を「旅」に喩えるように,典型的には抽象的な対象を具象的なものに見立てて表現する. | 人生は旅だ.彼女は氷の塊だ. |

| 直喩 | 明喩,シミリー (simile) | 「?のよう」などによって類似性を直接示す比喩.しばしばどの点で似ているのかも明示する. | ヤツはスッポンのようだ. |

| 擬人法 | パーソニフィケーション (personification) | 人間以外のものを人間に見立てて表現する比喩.隠喩の一種.ことばが人間中心に仕組まれていることを例証する. | 社会が病んでいる.母なる大地. |

| 共感覚法 | シネスシージア (synesthesia) | 触覚,味覚,嗅覚,視覚,聴覚の五感の間で表現をやりとりする表現法.表現を貸す側と借りる側との間で,一定の組み合わせがある. | 深い味.大きな音.暖かい色. |

| くびき法 | ジューグマ (zeugma) | 一本のくびきで二頭の牛をつなぐように,ひとつの表現を二つの意味で使う表現法.多義語の異なった意義を利用する. | バッターも痛いがピッチャーも痛かった. |

| 換喩 | メトニミー (metonymy) | 「赤ずきん」が「赤ずきんちゃん」を指すように,世界の中でのものとものの隣接関係にもとづいて指示を横すべりさせる表現法. | 鍋が煮える.春雨やものがたりゆく蓑と傘. |

| 提喩 | シネクドキ (synecdoche) | 「天気」で「いい天気」を意味する場合があるように,類と種の間の関係にもとづいて意味範囲を伸縮させる表現法. | 熱がある.焼き鳥.花見に行く. |

| 誇張法 | ハイパーバリー (hyperbole) | 事実以上に大げさな言いまわし.「猫の額」のように事実を過小に表現する場合もあるが,これも大げさな表現法の一種. | 一日千秋の思い.白髪三千丈.ノミの心臓. |

| 緩叙法 | マイオーシス (meiosis) | 表現の程度をひかえることによって,かえって強い意味を示す法.ひかえめなことばを使うか,「ちょっと」などを添える. | 好意をもっています.ちょつとうれしい. |

| 曲言法 | ライトティーズ (litotes) | 伝えたい意味の反対の表現を否定することによって,伝えたい意味をかえって強く表現する方法. | 悪くない.安い買い物ではなかった. |

| 同語反復法 | トートロジー (tautology) | まったく同じ表現を結びつけることによって,なおかつ意味をなす表現法.ことばの慣習的な意味を再確認させる. | 殺入は殺人だ.男の子は男の子だ. |

| 撞着法 | 対義結合,オクシモロン (oxymoron) | 正反対の意味を組み合わせて,なおかつ矛盾に陥らずに意味をなす表現法.「反対物の一致」を体現する. | 公然の秘密.暗黒の輝き.無知の知. |

| 婉曲法 | ユーフェミズム (euphemism) | 直接言いにくいことばを婉曲的に口当たりよく表現する方法.白魔術的な善意のものと黒魔術的な悪徳のものとがある. | 化粧室.生命保険.政治献金. |

| 逆言法 | パラレプシス (paralepsis) | 言わないといって実際には言う表現法.慣用的なものから滑稽なものまである.否定の逆説的な用い方. | 言うまでもなく.お礼の言葉もありません. |

| 修辞的疑問法 | レトリカル・クエスチョン (rhetorical questions) | 形は疑問文で意味は平叙文という表現法.文章に変化を与えるだけでなく,読者・聞き手に訴えかけるダイアローグ的特質をもつ. | いったい疑問の余地はあるのだろうか. |

| 含意法 | インプリケーション (implication) | 伝えたい意味を直接言うのではなく,ある表現から推論される意味によって間接的に伝える方法.会話のルールの意図的な違反によって含意が生じる. | 袖をぬらす.ちょっとこの部屋蒸すねえ. |

| 反復法 | リピティション (repetition) | 同じ表現を繰り返すことによって,意味の連続,リズム,強調を表す法.詩歌で用いられるものはリフレーンと呼ばれる. | えんやとっと,えんやとっと. |

| 挿入法 | パレンシシス (parenthesis) | カッコやダッシュなどの使用によって,文章の主流とは異なることばを挿入する表現法.ときに「脱線」ともなる. | 文は人なり(人は文なりというべきか). |

| 省略法 | エリプシス (ellipsis) | 文脈から復元できる要素を省略し,簡潔で余韻のある表現を生む方法.日本語ではこの技法が発達している. | これはどうも.それはそれは. |

| 黙説法 | レティセンス (reticence) | 途中で急に話を途絶することによって,内心のためらいや感動,相手への強い働きかけを表す.はじめから沈黙することもある. | 「……」.「――」. |

| 倒置法 | インヴァージョン (inversion) | 感情の起伏や力点の置き所を調整するために,通常の語順を逆転させる表現法.ふつう後置された要素に力点が置かれる. | うまいねえ,このコーヒーは. |

| 対句法 | アンティセシス (anthithesis) | 同じ構文形式のなかで意味的なコントラストを際だたせる表現法.対照的な意味が互いを照らしだす. | 春は曙.冬はつとめて. |

| 声喩 | オノマトペ (onomatopoeia) | 音が表現する意味に創意工夫を凝らす表現法一般を指す.擬音語・擬態語はその例のひとつ.頭韻や脚韻もここに含まれる. | かっぱらっぱかっぱらった. |

| 漸層法 | クライマックス (climax) | しだいに盛り上げてピークを形成する表現法.ひとつの文のなかでも,また,ひとつのテクスト全体のなかでも可能である. | 一度でも…,一度でも…,一度でも…. |

| 逆説法 | パラドクス (paradox) | 一般に真実だと想定されていることの逆を述べて,そこにも真実が含まれていることを伝える表現法. | アキレスは亀を追いぬくことはできない. |

| 諷喩 | アレゴリー (allegory) | 一貫したメタファーの連続からなる文章(テクスト).動物などを擬人化した寓話 (fable) は,その一種である. | 行く河の流れは絶えずして…. |

| 反語法 | 皮肉,アイロニー (irony) | 相手のことばを引用してそれとなく批判を加える表現法.また,意味を反転させて皮肉るのも反語である. | 〔0点に対して〕ほんといい点数ねえ. |

| 引喩 | アルージョン (allusion) | 有名な一節を暗に引用しながら独白の意味を加えることによって,重層的な意味をかもし出す法.本歌取りはその一例. | 盗めども盗めどもわが暮らし楽にならざる. |

| パロディー | もじり (parody) | 元の有名な文章や定型パタンを茶化しながら引用する法.内容を換骨奪胎して,批判・おかしみなどを伝える. | サラダ記念日.カラダ記念日. |

| 文体模写法 | パスティーシュ (pastiche) | 特定の作家・作者の文体をまねることによって,独.白の内容を盛り込む法.文体模写は文体のみを借用する. | (例文省略) |

・ 瀬戸 賢一 『日本語のレトリック』 岩波書店〈岩波ジュニア新書〉,2002年.

2015-04-23 Thu

■ #2187. あらゆる語の意味がメタファーである [metaphor][synaesthesia][semantic_change][semantics][etymology][rhetoric][unidirectionality][terminology]

言葉のあや (figure of speech) のなかでも,王者といえるのが比喩 (metaphor) である.動物でもないのに椅子の「あし」というとき,星でもないのに人気歌手を指して「スター」というとき,なめてみたわけではないのに「甘い」声というとき,比喩が用いられている.比喩表現があまりに言い古されて常套語句となったときには,比喩の作用がほとんど感じられなくなり,死んだメタファー (dead metaphor) と呼ばれる.日本語にも英語にも死んだメタファーがあふれており,あらゆる語の意味がメタファーであるとまで言いたくなるほどだ.

metaphor においては,比較の基準となる source と比較が適用される target の2つが必要である.椅子の一部の例でいえば,source は人間や動物の脚であり,target は椅子の支えの部分である.かたや生き物の世界のもの,かたや家具の世界のものである点で,source と target は2つの異なるドメイン (domain) に属するといえる.この2つは互いに関係のない独立したドメインだが,「あし」すなわち「本体の下部にあって本体を支える棒状のもの」という外見上,機能上の共通項により,両ドメイン間に橋が架けられる.このように,metaphor には必ず何らかの類似性 (similarity) がある.

「#2102. 英語史における意味の拡大と縮小の例」 ([2015-01-28-1]) で例をたくさん提供してくれた Williams は,metaphor の例も豊富に与えてくれている (184--85) .以下の語彙は,いずれも一見するところ metaphor と意識されないものばかりだが,本来の語義から比喩的に発展した語義を含んでいる.それぞれについて,何が source で何が target なのか,2つのドメインはそれぞれ何か,橋渡しとなっている共通項は何かを探ってもらいたい.死んだメタファーに近いもの,原義が忘れ去られているとおぼしきものについては,本来の語義や比喩の語義がそれぞれ何かについてヒントが与えられている(かっこ内に f. とあるものは原義を表わす)ので,参照しながら考慮されたい.

1. abstract (f. draw away from)

2. advert (f. turn to)

3. affirm (f. make firm)

4. analysis (f. separate into parts)

5. animal (You animal!)

6. bright (a bright idea)

7. bitter (sharp to the taste: He is a bitter person)

8. brow (the brow of a hill)

9. bewitch (a bewitching aroma)

10. bat (You old bat!)

11. bread (I have no bread to spend)

12. blast (We had a blast at the party)

13. blow up (He blew up in anger)

14. cold (She was cold to me)

15. cool (Cool it,man)

16. conceive (f. to catch)

17. conclude (f. to enclose)

18. concrete (f. to grow together)

19. connect (f. to tie together)

20. cut (She cut me dead)

21. crane (the derrick that resembles the bird)

22. compose (f. to put together)

23. comprehend (f. seize)

24. cat (She's a cat)

25. dig (I dig that idea)

26. deep (deep thoughts)

27. dark (I'm in the dark on that)

28. define (f. place limits on)

29. depend (f. hang from)

30. dog (You dog!)

31. dirty (a dirty mind)

32. dough (money)

33. drip (He's a drip)

34. drag (This class is a drag)

35. eye (the eye of a hurricane)

36. exist (f. stand out)

37. explain (f. make flat)

38. enthrall (f. to make a slave of)

39. foot (foot of a mountain)

40. fuzzy (I'm fuzzy headed)

41. finger (a finger of land)

42. fascinate (f. enchant by witchcraft)

43. flat (a flat note)

44. get (I don't get it)

45. grasp (I grasped the concept)

46. guts (He has a lot of guts)

47. groove (I'm in the groove)

48. gas (It was a gasser)

49. grab (How does the idea grab you?)

50. high (He got high on dope)

51. hang (He's always hung up)

52. heavy (I had a heavy time)

53. hot (a hot idea)

54. heart (the heart of the problem)

55. head (head of the line)

56. hands (hands of the clock)

57. home (drive the point home)

58. jazz (f. sexual activity)

59. jive (I don't dig this jive)

60. intelligent (f. bring together)

61. keen (f. intelligent)

62. load (a load off my mind)

63. long (a long lime)

64. loud (a loud color)

65. lip (lip of the glass)

66. lamb (She's a lamb)

67. mouth (mouth of a cave)

68. mouse (You're a mouse)

69. milk (He milked the job dry)

70. pagan (f. civilian, in distinction to Christians, who called themselves soldiers of Christ)

71. pig (You pig)

72. quiet (a quiet color)

73. rip-off (It was a big rip-off)

74. rough (a rough voice)

75. ribs (the ribs of a ship)

76. report (f. to carry back)

77. result (f. to spring back)

78. shallow (shallow ideas)

79. soft (a soft wind)

80. sharp (a sharp dresser)

81. smooth (a smooth operator)

82. solve (f. to break up)

83. spirit (f. breath)

84. snake (You snake!)

85. straight (He's a straight guy)

86. square (He's a square)

87. split (Let's split)

88. turn on (He turns me on)

89. trip (It was a bad (drug) trip)

90. thick (a voice thick with anger)

91. thin (a thin sound)

92. tongue (a tongue of land)

93. translate (f. carry across)

94. warm (a warm color)

95. wrestle (I wrestled with the problem)

96. wild (a wild idea)

ラテン語由来の語が多く含まれているが,一般に多形態素からなるラテン借用語は,今日の英語では(古典ラテン語においてすら)原義として用いられるよりも,比喩的に発展した語義で用いられることのほうが多い.体の部位や動物を表わす語は比喩の source となることが多く,共感覚 (synaesthesia) の事例も多い.また,比喩的な語義が,俗語的な響きをもつ例も少なくない.

このように比喩にはある種の特徴が見られ,それは通言語的にも広く観察されることから,意味変化の一般的傾向を論じることが可能となる.これについては,「#1759. synaesthesia の方向性」 ([2014-02-19-1]),「#1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性」 ([2014-09-03-1]),「#2101. Williams の意味変化論」 ([2015-01-27-1]) などの記事を参照.

・ Williams, Joseph M. Origins of the English Language: A Social and Linguistic History. New York: Free P, 1975.

2014-09-03 Wed

■ #1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性 [semantic_change][semantics][synaesthesia][rhetoric][grammaticalisation][prediction_of_language_change][speed_of_change][function_of_language][subjectification]

語の意味変化が予測不可能であることは,他の言語変化と同様である.すでに起こった意味変化を研究することは重要だが,そこからわかることは意味変化の一般的な傾向であり,将来の意味変化を予測させるほどの決定力はない.「#1756. 意味変化の法則,らしきもの?」 ([2014-02-16-1]) で「法則」の名に値するかもしれない意味変化の例を見たが,もしそれが真実だとしても例外中の例外といえるだろう.ほとんどは,「#473. 意味変化の典型的なパターン」 ([2010-08-13-1]) や「#1109. 意味変化の原因の分類」 ([2012-05-10-1]),「#1873. Stern による意味変化の7分類」 ([2014-06-13-1]),「#1953. Stern による意味変化の7分類 (2)」 ([2014-09-01-1]) で示唆されるような意味変化の一般的な傾向である.

Brinton and Arnovick (87) は,次のような傾向を指摘している.

・ 素早く起こる.そのために辞書への登録が追いつかないこともある.ex. desultory (slow, aimlessly, despondently), peruse (to skim or read casually)

・ 具体的な意味から抽象的な意味へ.ex. understand

・ 中立的な意味から非中立的な意味へ.ex. esteem (cf. 「#1099. 記述の形容詞と評価の形容詞」 ([2012-04-30-1]),「#1100. Farsi の形容詞区分の通時的な意味合い」 ([2012-05-01-1]),「#1400. relational adjective から qualitative adjective への意味変化の原動力」 ([2013-02-25-1]))

・ 強い感情的な意味が弱まる傾向.ex. awful

・ 侮辱的な語は動物や下級の人々を表わす表現から.ex. rat, villain

・ 比喩的な表現は日常的な経験に基づく.ex. mouth of a river

・ 文法化 (grammaticalisation) の一方向性

・ 不規則変化は,言語外的な要因にさらされやすい名詞にとりわけ顕著である

もう1つ,意味変化の一般的な傾向というよりは,それ自体の特質と呼ぶべきだが,言語において意味変化が何らかの形でとかく頻繁に生じるということは明言してよい事実だろう.上で参照した Brinton and Arnovick も,"Of all the components of language, lexical meaning is most susceptible to change. Semantics is not rule-governed in the same way that grammar is because the connection between sound and meaning is arbitrary and conventional." (76) と述べている.また,意味変化の日常性について,前田 (106) は以下のように述べている.

とかく口語・俗語では意味の変化が活発である.これに比べると,文法の変化はかなりまれで,おそらく一生のうちでそれと気づくものはわずかだろう.音の変化は,日本語の「ら抜きことば」のように,もう少し気づかれやすいが,それでも意味変化の豊富さに比べれば目立たない.では,なぜ意味変化 (semantic change) はこれほど頻繁に起こるのだろうか.その答えは,おそらく意味変化がディスコース (discourse) における日常的営みから直接生ずるものだからである.

最後の文を言い換えて,前田 (130) は「意味の伝達が日常の言語活動の舞台であるディスコースにおけるコミュニケーション活動の目的と直接結びついているからである」と結論している.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

・ 前田 満 「意味変化」『意味論』(中野弘三(編)) 朝倉書店,2012年,106--33頁.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow