2014-12-09 Tue

■ #2052. 英語史における母音の主要な質的・量的変化 [phonetics][vowel][meosl][homorganic_lengthening][gvs][diphthong][timeline][drift][compensatory_lengthening][shocc]

西ゲルマン語の時代から古英語,中英語を経て近代英語に至るまでの英語の母音の歴史をざっとまとめた一覧が欲しいと思ったので,主要な質的・量的変化をまとめてみた.以下の表は,Görlach (48--49) の母音の質と量に関する変化の略年表をドッキングしたものである.

| Period | Quantity | Quality | ||

| Rule | Examples | Rule | Examples | |

| WGmc--OE | ai > ā, au > ēa, ā > ǣ/ē, a > æ | stān, ēage, dǣd, dæg cf. Ge Stein, Auge, Tat, Tag | ||

| 7--9th c. | compensatory lengthening | *sehan > sēon "see", mearh, gen. mēares "mare" | ||

| 9--10th c. | lengthening of before esp. [-ld, -mb, -nd] | fēld, gōld, wāmb, fīnd, but ealdrum | ||

| shortening before double (long) consonants | wĭsdom, clæ̆nsian, cĭdde, mĕtton | |||

| shortening in the first syllable of trisyllabic words | hăligdæg, hæ̆ringas, wĭtega | |||

| OE--ME | shortening in unstressed syllables | wisdŏm, stigrăp | monophthongization of all OE diphthongs | OE dēad, heard, frēond, heorte, giefan > ME [dɛːd, hard, frœːnd, hœrtə, jivən] |

| 12th c. | [ɣ > w] and vocalization of [w] and [j]; emergence of new diphthongs | OE dagas, boga, dæg, weg > ME [dauəs, bouə, dai, wei] | ||

| southern rounding of [aː > ɔː] | OE hāl(ig) > ME hool(y) [ɔː] | |||

| 12--14th c. | unrounding of œ(ː), y(ː) progressing from east to west | ME [frɛːnd, hertə, miːs, fillen] | ||

| 13th c. | lengthening in open syllables of bisyllabic words | nāme, nōse, mēte (week, door) | ||

| 15th c. GVS and 16--17th century consequences | ||||

| esp. 15--16th c. | shortening in monosyllabic words | dead, death, deaf, hot, cloth, flood, good | ||

| 18th c. | lengthening before voiceless fricatives and [r] | glass, bath, car, servant, before | ||

全体として質の変化よりも量の変化,すなわち短化と長化の傾向が勝っており,英語の母音がいかに伸縮を繰り返してきたかが分かる.個々の変化は入出力の関係にあるものもあるが,結果としてそうなったのであり,歴史的には各々独立して生じたことはいうまでもない.それでも,これらの音韻変化を全体としてとらえようとする試みもあることを指摘しておこう.例えば「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

2014-10-05 Sun

■ #1987. ピジン語とクレオール語の非連続性 [pidgin][creole][drift][post-creole_continuum][sociolinguistics][founder_principle]

ピジン語 (pidgin) とクレオール語 (creole) についての一般の理解によると,前者が母語話者をもたない簡易化した混成語にとどまるのに対し,後者は母語話者をもち,体系的な複雑化に特徴づけられる言語ということである.別の言い方をすれば,creole は pidgin から発展した段階の言語を表わし,両者はある種の言語発達のライフサイクルの一部を構成する(その後,post-creole_continuum や decreolization の段階がありうるとされる).両者は連続体ではあるものの,「#1690. pidgin とその関連語を巡る定義の問題」 ([2013-12-12-1]) で示したように,諸特徴を比較すれば相違点が目立つ.

しかし,「#444. ピジン語とクレオール語の境目」 ([2010-07-15-1]) でも触れたように,pidgin と creole には上記のライフサイクル的な見方に当てはまらない例がある.ピジン語のなかには,母語話者を獲得せずに,すなわち creole 化せずに,体系が複雑化する "expanded pidgin" が存在する.「#412. カメルーンの英語事情」 ([2010-06-13-1]),「#413. カメルーンにおける英語への language shift」 ([2010-06-14-1]) で触れた Cameroon Pidgin English,「#1688. Tok Pisin」 ([2013-12-10-1]) で取り上げた Tok Pisin のいくつかの変種がその例である.また,反対に,大西洋やインド洋におけるように,ピジン語の段階を経ずに直接クレオール語が生じたとみなされる例もある (Mufwene 48) .

クレオール語研究の最先端で仕事をしている Mufwene (47) は,伝統的な理解によるピジン語とクレオール語のライフサイクル説に対して懐疑的である.とりわけ expanded pidgin とcreole の関係について,両者は向かっている方向がむしろ逆であり,連続体とみなすのには無理があるとしている.

There are . . . significant reasons for not lumping expanded pidgins and creoles in the same category, usually identified as creole and associated with the fact that they have acquired a native speaker population. . . . [T]hey evolved in opposite directions, although they are all associated with plantation colonies, with the exception of Hawaiian Creole, which actually evolved in the city . . . . Creoles started from closer approximations of their 'lexifiers' and then evolved gradually into basilects that are morphosyntactically simpler, in more or less the same ways as their 'lexifiers' had evolved from morphosyntactically more complex Indo-European varieties, such as Latin or Old English. According to Chaudenson (2001), they extended to the logical conclusion a morphological erosion that was already under way in the nonstandard dialects of European languages that the non-Europeans had been exposed to. On the other hand, expanded pidgins started from rudimentary language varieties that complexified as their functions increased and diversified.

引用内で触れられている Chaudenson も同じ趣旨で論じているように,creole は語彙提供言語(通常は植民地支配者たるヨーロッパの言語)と地続きであり,それが簡易化したものであるという解釈だ (cf. 「#1842. クレオール語の歴史社会言語学的な定義」 ([2014-05-13-1])) .一方,pidgin は語彙提供言語とは区別されるべき混成語であり,その発展形である expanded pidgin は pidgin が徐々に多機能化し,複雑化してきた変種を指すという考えだ.つまり,広く受け入れられている pidgin → expanded pidgin → creole という発展のライフサイクル観は,事実を説明しない.実際,19世紀終わりまでは pidgin と creole の間にこのような発展的な関係は前提とされていなかった.言語学史的には,20世紀に入ってから Bloomfield などが発展関係を指摘し始めたにすぎない (Mufwene 48) .

creole が,印欧諸語の単純化の偏流 (drift) の論理的帰結であるという主張は目から鱗が落ちるような視点だ.Mufwene の次の指摘にも目の覚める思いがする."Had linguists remembered that the European 'lexifiers' had actually evolved from earlier, more complex morphosyntaxes, they would have probably taken into account more of the socioeconomic histories of the colonies, which suggest a parallel evolution" (48) .

Mufwene のクレオール語論,特に植民地史における homestead stage と plantation stage の区別と founder principle については,「#1840. スペイン語ベースのクレオール語が極端に少ないのはなぜか」 ([2014-05-11-1]) と「#1841. AAVE の起源と founder principle」 ([2014-05-12-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Mufwene, Salikoko. "Creoles and Creolization." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 46--60.

2014-09-27 Sat

■ #1979. 言語変化の目的論について再考 [language_change][causation][teleology][unidirectionality][invisible_hand][drift][functionalism]

昨日の記事で引用した Luraghi が,同じ論文で言語変化の目的論 (teleology) について論じている.teleology については本ブログでもたびたび話題にしてきたが,論じるに当たって関連する諸概念について整理しておく必要がある.

まず,言語変化は therapy (治療)か prophylaxis (予防)かという議論がある.「#835. 機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」 ([2011-08-10-1]) や「言語変化における therapy or pathogeny」 ([2011-08-12-1]) で取り上げた問題だが,いずれにしても前提として機能主義的な言語変化観 (functionalism) がある.Kiparsky は "language practices therapy rather than prophylaxis" (Luraghi 364) との謂いを残しているが,Lass などはどちらでもないとしている.

では,functionalism と teleology は同じものなのか,異なるものなのか.これについても,諸家の間で意見は一致していない.Lass は同一視しているようだが,Croft などの論客は前者は "functional proper",後者は "systemic functional" として区別している."systemic functional" は言語の teleology を示すが,"functional proper" は話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムを指す.あくまで話者の意図にかかわるメカニズムとしての "functional" という表現が,変異や変化を示す言語項についても応用される限りにおいて,(話者のではなく)言語の "functionalism" を語ってもよいかもしれないが,それが言語の属性を指すのか話者の属性を指すのかを区別しておくことが重要だろう.

Teleological explanations of language change are sometimes considered the same as functional explanations . . . . Croft . . . distinguishes between 'systemic functional,' that is teleological, explanations, and 'functional proper,' which refer to intentional mechanisms. Keller . . . argues that 'functional' must not be confused with 'teleological,' and should be used in reference to speakers, rather than to language: '[t]he claim that speakers have goals is correct, while the claim that language has a goal is wrong' . . . . Thus, to the extent that individual variants may be said to be functional to the achievement of certain goals, they are more likely to generate language change through invisible hand processes: in this sense, explanations of language change may also be said to be functional. (Luraghi 365--66)

上の引用にもあるように,重要なことは「言語が変化する」と「話者が言語を刷新する」とを概念上区別しておくことである.「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」 ([2013-07-24-1]) で述べたように,この区別自体にもある種の問題が含まれているが,あくまで話者(集団)あっての言語であり,言語変化である.話者主体の言語変化論においては teleology の占める位置はないといえるだろう.Luraghi (365) 曰く,

Croft . . . warns against the 'reification or hypostatization of languages . . . Languages don't change; people change language through their actions.' Indeed, it seems better to avoid assuming any immanent principles inherent in language, which seem to imply that language has an existence outside the speech community. This does not necessarily mean that language change does not proceed in a certain direction. Croft rejects the idea that 'drift,' as defined by Sapir . . ., may exist at all. Similarly, Lass . . . wonders how one can positively demonstrate that the unconscious selection assumed by Sapir on the side of speakers actually exists. From an opposite angle, Andersen . . . writes: 'One of the most remarkable facts about linguistic change is its determinate direction. Changes that we can observe in real time---for instance, as they are attested in the textual record---typically progress consistently in a single direction, sometimes over long periods of time.' Keller . . . suggests that, while no drift in the Sapirian sense can be assumed as 'the reason why a certain event happens,' i.e., it cannot be considered innate in language, invisible hand processes may result in a drift. In other words, the perspective is reversed in Keller's understanding of drift: a drift is not the pre-existing reason which leads the directionality of change, but rather the a posteriori observation of a change brought about by the unconsciously converging activity of speakers who conform to certain principles, such as the principle of economy and so on . . . .

関連して drift, functionalism, invisible_hand, unidirectionality の各記事も参考にされたい.

・ Luraghi, Silvia. "Causes of Language Change." Chapter 20 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 358--70.

2014-09-23 Tue

■ #1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2) [grammaticalisation][unidirectionality][pragmatics][subjectification][invisible_hand][teleology][drift][reanalysis][iconicity][exaptation][terminology][toc]

昨日の記事「#1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1)」 ([2014-09-22-1]) を受けて,文法化 (grammaticalisation) 研究の守備範囲の広さについて補足する.Bussmann (196--97) によると,文法化がとりわけ関心をもつ疑問には次のようなものがある.

(a) Is the change of meaning that is inherent to grammaticalization a process of desemanticization, or is it rather a case (at least in the early stages of grammaticalization) of a semantic and pragmatic concentration?

(b) What productive parts do metaphors and metonyms play in grammaticalization?

(c) What role does pragmatics play in grammaticalization?

(d) Are there any universal principles for the direction of grammaticalization, and, if so, what are they? Suggestions for such 'directed' principles include: (i) increasing schematicization; (ii) increasing generalization; (iii) increasing speaker-related meaning; and (iv) increasing conceptual subjectivity.

昨日記した守備範囲と合わせて,文法化研究の潜在的なカバレッジの広さと波及効果の大きさを感じることができる.また,秋元 (vii) の目次より文法化理論に関連する用語を拾い出すだけでも,この分野が言語研究の根幹に関わる諸問題を含む大項目であることがわかるだろう.

第1章 文法化

1.1 序

1.2 文法化とそのメカニズム

1.2.1 語用論的推論 (Pragmatic inferencing)

1.2.2 漂白化 (Bleaching)

1.3 一方向性 (Unidirectionality)

1.3.1 一般化 (Generalization)

1.3.2 脱範疇化 (Decategorialization)

1.3.3 重層化 (Layering)

1.3.4 保持化 (Persistence)

1.3.5 分岐化 (Divergence)

1.3.6 特殊化 (Specialization)

1.3.7 再新化 (Renewal)

1.4 主観化 (Subjectification)

1.5 再分析 (Reanalysis)

1.6 クラインと文法化連鎖 (Grammaticalization chains)

1.7 文法化とアイコン性 (Iconicity)

1.8 文法化と外適応 (Exaptation)

1.9 文法化と「見えざる手」 (Invisible hand) 理論

1.10 文法化と「偏流」 (Drift) 論

文法化は,主として言語の通時態に焦点を当てているが,一方で主として共時的な認知文法 (cognitive grammar) や機能文法 (functional grammar) とも親和性があり,通時態と共時態の交差点に立っている.そこが,何よりも魅力である.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ 秋元 実治 『増補 文法化とイディオム化』 ひつじ書房,2014年.

2014-09-19 Fri

■ #1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か? [drift][grammaticalisation][generative_grammar][syntax][auxiliary_verb][teleology][language_change][unidirectionality][causation][diachrony]

Lightfoot は,言語の歴史における 文法化 (grammaticalisation) は言語変化の原理あるいは説明でなく,結果の記述にすぎないとみている."Grammaticalisation, challenging as a phenomenon, is not an explanatory force" (106) と,にべもなく一蹴だ.文法化の一方向性を,"mystical" な drift (駆流)の方向性になぞらえて,その目的論 (teleology) 的な言語変化観を批判している.

Lightfoot は,一見したところ文法化とみられる言語変化も,共時的な "local cause" によって説明できるとし,その例として彼お得意の法助動詞化 (auxiliary_verb) の問題を取り上げている.本ブログでも「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1]) や「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) で紹介した通り,Lightfoot は生成文法の枠組みで,子供の言語習得,UG (Universal Grammar),PLD (Primary Linguistic Data) の関数として,can や may など歴史的な動詞の法助動詞化を説明する.この「文法化」とみられる変化のそれぞれの段階において変化を駆動する local cause が存在することを指摘し,この変化が全体として mystical でもなければ teleological でもないことを示そうとした.非歴史的な立場から local cause を究明しようという Lightfoot の共時的な態度は,その口から発せられる主張を聞けば,Saussure よりも Chomsky よりも苛烈なもののように思える.そこには共時態至上主義の極致がある.

Time plays no role. St Augustine held that time comes from the future, which doesn't exist; the present has no duration and moves on to the past which no longer exists. Therefore there is no time, only eternity. Physicists take time to be 'quantum foam' and the orderly flow of events may really be as illusory as the flickering frames of a movie. Julian Barbour (2000) has argued that even the apparent sequence of the flickers is an illusion and that time is nothing more than a sort of cosmic parlor trick. So perhaps linguists are better off without time. (107)

So we take a synchronic approach to history. Historical change is a kind of finite-state Markov process: changes have only local causes and, if there is no local cause, there is no change, regardless of the state of the grammar or the language some time previously. . . . Under this synchronic approach to change, there are no principles of history; history is an epiphenomenon and time is immaterial. (121)

Lightfoot の方法論としての共時態至上主義の立場はわかる.また,local cause の究明が必要だという主張にも同意する.drift (駆流)と同様に,文法化も "mystical" な現象にとどまらせておくわけにはいかない以上,共時的な説明は是非とも必要である.しかし,Lightfoot の非歴史的な説明の提案は,例外はあるにせよ文法化の著しい傾向が多くの言語の歴史においてみられるという事実,そしてその理由については何も語ってくれない.もちろん Lightfoot は文法化は歴史の付帯現象にすぎないという立場であるから,語る必要もないと考えているのだろう.だが,文法化を歴史的な流れ,drift の一種としてではなく,言語変化を駆動する共時的な力としてみることはできないのだろうか.

・ Lightfoot, David. "Grammaticalisation: Cause or Effect." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 99--123.

2014-04-17 Thu

■ #1816. drift 再訪 [drift][gvs][germanic][synthesis_to_analysis][language_change][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][causation][functionalism]

Millar (111--13) が,英語史における古くて新しい問題,drift (駆流)を再訪している(本ブログ内の関連する記事は,cat:drift を参照).

Sapir の唱えた drift は,英語なら英語という1言語の歴史における言語変化の一定方向性を指すものだったが,後に drift の概念は拡張され,関連する複数の言語に共通してみられる言語変化の潮流をも指すようになった.これによって,英語の drift は相対化され,ゲルマン諸語にみられる drifts の比較,とりわけ drifts の速度の比較が問題とされるようになった.Millar (112) も,このゲルマン諸語という視点から,英語史における drift の問題を再訪している.

A number of scholars . . . take Sapir's ideas further, suggesting that drift can be employed to explain why related languages continue to act in a similar manner after they have ceased to be part of a dialect continuum. Thus it is striking . . . that a very similar series of sound changes --- the Great Vowel Shift --- took place in almost all West Germanic varieties in the late medieval and early modern periods. While some of the details of these changes differ from language to language, the general tendency for lower vowels to rise and high vowels to diphthongise is found in a range of languages --- English, Dutch and German --- where immediate influence along a geographical continuum is unlikely. Some linguists would suggest that there was a 'weakness' in these languages which was inherited from the ancestral variety and which, at the right point, was triggered by societal forces --- in this case, the rise of a lower middle class as a major economic and eventually political force in urbanising societies.

これを書いている Millar 自身が,最後の文の主語 "Some linguists" のなかの1人である.Samuels 流の機能主義的な観点に,社会言語学的な要因を考え合わせて,英語の drift を体現する個々の言語変化の原因を探ろうという立場だ.Sapir の drift = "mystical" というとらえ方を退け,できる限り合理的に説明しようとする立場でもある.私もこの立場に賛成であり,とりわけ社会言語学的な要因の "trigger" 機能に関心を寄せている.関連して,「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) や「#1224. 英語,デンマーク語,アフリカーンス語に共通してみられる言語接触の効果」 ([2012-09-02-1]) も参照されたい.

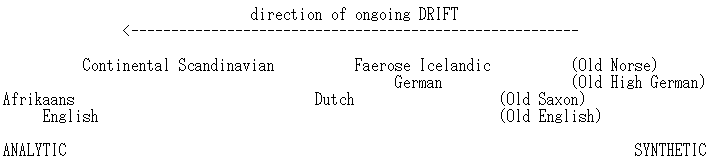

ゲルマン諸語の比較という点については,Millar (113) は,drift の進行の程度を模式的に示した図を与えている.以下に少し改変した図を示そう(かっこに囲まれた言語は,古い段階での言語を表わす).

この図は,「#191. 古英語,中英語,近代英語は互いにどれくらい異なるか」 ([2009-11-04-1]) で示した Lass によるゲルマン諸語の「古さ」 (archaism) の数直線を別の形で表わしたものとも解釈できる.その場合,drift の進行度と言語的な「モダンさ」が比例の関係にあるという読みになる.

この図では,English や Afrikaans が ANALYTIC の極に位置しているが,これは DRIFT が完了したということを意味するわけではない.現代英語でも,DRIFT の継続を感じさせる言語変化は進行中である.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-01-19 Sun

■ #1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観 [language_change][teleology][evolution][unidirectionality][drift][history_of_linguistics][artificial_language][language_myth]

英語史の授業で英語が経てきた言語変化を概説すると,「言語はどんどん便利な方向へ変化してきている」という反応を示す学生がことのほか多い.これは,「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) の (2) に挙げた「言語変化はより効率的な状態への緩慢な進歩である」と同じものであり,言語進歩観とでも呼ぶべきものかもしれない.しかし,その記事でも述べたとおり,言語変化は進歩でも堕落でもないというのが現代の言語学者の大方の見解である.ところが,かつては,著名な言語学者のなかにも,言語進歩観を公然と唱える者がいた.デンマークの英語学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) もその1人である.

. . . in all those instances in which we are able to examine the history of any language for a sufficient length of time, we find that languages have a progressive tendency. But if languages progress towards greater perfection, it is not in a bee-line, nor are all the changes we witness to be considered steps in the right direction. The only thing I maintain is that the sum total of these changes, when we compare a remote period with the present time, shows a surplus of progressive over retrogressive or indifferent changes, so that the structure of modern languages is nearer perfection than that of ancient languages, if we take them as wholes instead of picking out at random some one or other more or less significant detail. And of course it must not be imagined that progress has been achieved through deliberate acts of men conscious that they were improving their mother-tongue. On the contrary, many a step in advance has at first been a slip or even a blunder, and, as in other fields of human activity, good results have only been won after a good deal of bungling and 'muddling along.' (326)

. . . we cannot be blind to the fact that modern languages as wholes are more practical than ancient ones, and that the latter present so many more anomalies and irregularities than our present-day languages that we may feel inclined, if not to apply to them Shakespeare's line, "Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms," yet to think that the development has been from something nearer chaos to something nearer kosmos. (366)

Jespersen がどのようにして言語進歩観をもつに至ったのか.ムーナン (84--85) は,Jespersen が1928年に Novial という補助言語を作り出した背景を分析し,次のように評している(Novial については「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]) を参照).

彼がそこへたどり着いたのはほかの人の場合よりもいっそう,彼の論理好みのせいであり,また,彼のなかにもっとも古くから,もっとも深く根をおろしていた理論の一つのせいであった.その理論というのは,相互理解の効率を形態の経済性と比較してみればよい,という考えかたである.それにつづくのは,平均的には,任意の一言語についてみてもありとあらゆる言語についてみても,この点から見ると,正の向きの変化の総和が不の向きの総和より勝っているものだ,という考えかたである――そして彼は,もっとも普遍的に確認されていると称するそのような「進歩」の例として次のようなものを列挙している.すなわち,音楽的アクセントが次第に単純化すること,記号表現部〔能記〕の短縮,分析的つまり非屈折的構造の発達,統辞の自由化,アナロジーによる形態の規則化,語の具体的な色彩感を犠牲にした正確性と抽象性の増大である.(『言語の進歩,特に英語を照合して』) マルティネがみごとに見てとったことだが,今日のわれわれにはこの著者のなかにあるユートピア志向のしるしとも見えそうなこの特徴が,実は反対に,ドイツの比較文法によって広められていた神話に対する当時としては力いっぱいの戦いだったのだと考えて見ると,実に具体的に納得がいく.戦いの相手というのは,諸言語の完全な黄金時期はきまってそれらの前史時代の頂点に位置しており,それらの歴史はつねに形態と構造の頽廃史である,という神話だ.(「語の研究」)

つまり,Jespersen は,当時(そして少なからず現在も)はやっていた「言語変化は完全な状態からの緩慢な堕落である」とする言語堕落観に対抗して,言語進歩観を打ち出したということになる.言語学史的にも非常に明快な Jespersen 評ではないだろうか.

先にも述べたように,Jespersen 流の言語進歩観は,現在の言語学では一般的に受け入れられていない.これについて,「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) 及び「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ ジョルジュ・ムーナン著,佐藤 信夫訳 『二十世紀の言語学』 白水社,2001年.

2013-11-26 Tue

■ #1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察 [synthesis_to_analysis][inflection][drift][high_vowel_deletion]

英語史,ゲルマン語史,印欧語史のいずれについても程度の差はあれ言えることだが,音韻変化による屈折語尾の水平化が,屈折体系という形態論の崩壊をもたらし,代わりに分析という統語的機構が発達してきた.音韻変化が形態と統語という文法部門に衝撃を与えた事例だが,この衝撃は直接のものなのか,間接のものなのか.とりわけ弱音節の音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化の関連,音韻論と形態論の関わりはどのようなものなのか.英語史などでもこの関連性はおよそ自明のこととして受け取られてきたが,理論的に考察される機会,少なくともそれが紹介される機会は少ない.この関連性の問題について,Bradley (16--19) の考察を示そう.

音韻変化が形態変化につながる場合,その音声変化の効果としては3種類が認められる.(1) confluent development, (2) divergent development, (3) dropping of sounds である.(1) は,異なる2つの音が1つに融合することにより,かつての形態的な区別が失われる場合である.古英語で区別されていた ā と o は,ある環境において融合し,現代英語では ō として実現されている (ex. hāl (whole) と fola (foal)) .

(2) は,逆に1つの音が2つに分かれることによって,形態的な区別が新たに生まれる場合である.例えば,古英語の ic lǣde (I lead) と ic lǣdde (I led) の動詞形態に注目すると,語幹音節が開音節か閉音節かという条件によって,後の語幹母音の発展が決まった.同じ ǣ が,環境によって異なる2音へと分岐したのである.

(3) の例としては,古英語において,それ以前に生じたとされる High Vowel Deletion と呼ばれる音韻変化の結果として,重音節に後続する -u 屈折語尾が現れないというものがある.中性強変化名詞では,単数の scip に対して複数は scipu だが,hūs は単複同形である.効果としては (1) と同じであり,もともと区別されていた2つの形態が1つへ融合してしまっている.

3種類の音韻変化の効果をまとめると,(1) と (3) は形態の区別を失わせる方向に,すなわち一見すると単純化の方向に働くのに対し,(2) は形態の区別を生み出す方向,すなわち一見すると複雑化の方向に働く.つまり,音韻変化には相反するかのような効果が同時に働いているということになる.しかし,文法の機能という観点からみると,その効果は一貫して非機能化の方向に働いているともいえるのである.Bradley (18) は,scip と hūs の例を念頭に,以下のように述べている.

In this instance phonetic change produced two different effects: it made two declensions out of one, and it deprived a great many words of a useful inflexional distinction. / We thus see that the direct result of phonetic change on the grammar of a language is chiefly for evil: it makes it more complicated and less lucid.

これは,音韻変化と屈折形態論との関係に関する,鋭い理論的な洞察である.

音韻変化が形態論のエントロピーを増大させることについては,「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1]) を参照.

・ Bradley, Henry. The Making of English. New York: Dover, 2006. New York: Macmillan, 1904.

2013-08-31 Sat

■ #1587. 印欧語史は言語のエントロピー増大傾向を裏付けているか? [drift][unidirectionality][synthesis_to_analysis][entropy][i-mutation][origin_of_language]

英語史のみならずゲルマン語史,さらには印欧語史の全体が,言語の単純化傾向を示しているように見える.ほとんどすべての印欧諸語で,性・数・格を始め種々の文法範疇の区分が時間とともに粗くなってきているし,形態・統語においては総合から分析へと言語類型が変化してきている.印欧語族に見られるこの駆流 (drift) については,「#656. "English is the most drifty Indo-European language."」 ([2011-02-12-1]) ほか drift の各記事で話題にしてきた.

しかし,この駆流を単純化と同一視してもよいのかという疑問は残る.むしろ印欧祖語は,文法範疇こそ細分化されてはいるが,その内部の体系は奇妙なほどに秩序正しかった.印欧祖語は,現在の印欧諸語と比べて,音韻形態的な不規則性は少ない.言語は時間とともに allomorphy を増してゆくという傾向がある.例えば i-mutation の歴史をみると,当初は音韻過程にすぎなかったものが,やがて音韻過程の脈絡を失い,純粋に形態的な過程となった.結果として,音韻変化を受けていない形態と受けた形態との allomorphy が生まれることになり,体系内の不規則性(エントロピー)が増大した([2011-08-13-1]の記事「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」を参照).さらに後になって,類推作用 (analogy) その他の過程により allomorphy が解消されるケースもあるが,原則として言語は時間とともにこの種のエントロピーが増大してゆくものと考えることができる.

だが,印欧語の歴史に明らかに見られると上述したエントロピーの増大傾向は,はたして額面通りに認めてしまってよいのだろうか.というのは,その出発点である印欧祖語はあくまで理論的に再建されたものにすぎないからである.もし再建者の頭のなかに言語はエントロピーの増大傾向を示すものだという仮説が先にあったとしたら,結果として再建される印欧祖語は,当然ながらそのような仮説に都合のよい形態音韻論をもった言語となるだろう.

実際に Comrie のような学者は,そのような仮説をもって印欧祖語をとらえている.Comrie (253) が想定しているのは,"an earlier stage of language, lacking at least many of the complexities of at least many present-day languages, but providing an explicit account of how these complexities could have arisen, by means of historically well-attested processes applied to this less complex earlier state" である.ここには,言語はもともと単純な体系として始まったが時間とともに複雑さを増してきたという前提がある.Comrie のこの前提は,次の箇所でも明確だ.

[I]t is unlikely that the first human language started off with the complexity of Insular Celtic morphophonemics or West Greenlandic morphology. Rather, such complexities arose as the result of the operation of attested processes --- such as the loss of conditioning of allophonic variation to give morphophonemic alternations or the grammaticalisation of lexical items to give grammatical suffixes --- upon an earlier system lacking such complexities, in which invariable words followed each other in order to build up the form corresponding to the desired semantic content, in an isolating language type lacking morphophonemic alternation. (250)

再建された祖語を根拠にして言語変化の傾向を追究することには慎重でなければならない.ましてや,先に傾向ありきで再建形を作り出し,かつ前提とすることは,さらに危ういことのように思える.Comrie (247) は印欧祖語再建に関して realist の立場([2011-09-06-1]) を明確にしているから,エントロピーが極小である言語の実在を信じているということになる.controversial な議論だろう.

・ Comrie, Barnard. "Reconstruction, Typology and Reality." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 243--57.

2013-08-23 Fri

■ #1579. 「言語は植物である」の比喩 [history_of_linguistics][language_myth][drift][language_change]

昨日の記事「#1578. 言語は何に喩えられてきたか」 ([2013-08-22-1]) で触れたが,19世紀に一世を風靡した言語有機体説の考え方は,21世紀の今でも巷間で根強く支持されている.端的にいえば,言語は生き物であるという言語観のことである.直感的ではあるが,言語についての多くの誤解を生み出す元凶でもあり,慎重に取り扱わなければならないと私は考えているが,これほどまでに人々の理解に深く染みこんでいる比喩を覆すことは難しい.

昨日の記事の (6) で見たとおり,言語は,生き物のなかでもとりわけ植物に喩えられることが多い.Aitchison (44--45) は,言語学史における「言語=植物」の言及を何点か集めている.3点を引用しよう(便宜のため,引用元の典拠は部分的に展開しておく).

Languages are to be considered organic natural bodies, which are formed according to fixed laws, develop as possessing an inner principle of life, and gradually die out because they do not understand themselves any longer, and therefore cast off or mutilate their members or forms (Franz Bopp 1827, in Jespersen [Language, Its Nature, Development and Origin] 1922: 65)

Does not language flourish in a favorable place like a tree whose way nothing blocks? . . . Also does it not become underdeveloped, neglected and dying away like a plant that had to languish or dry out from lack of light or soil? (Grimm [On the Origin of Language. Trans. R. A. Wiley.] 1851)

De même que la plante est modifiée dans son organisme interne par des facteurs étrangers: terrain, climat, etc., de même l'organisme grammatical ne dépend-il pas constamment des facteurs externes du changement linguistique?... Est-il possible de distinguer le développment naturel, organique d'un idiome, de ses formes artificielles, telles que la language littéraire, qui sont dues à des facteurs externes, par conséquent inorganiques? (Saussure 1968 [1916] [Cours de linguistique générale]: 41--2)

いずれも直接あるいは間接に言語有機体説を体現しているといってよいだろう.Grimm の比喩からは「#1502. 波状理論ならぬ種子拡散理論」 ([2013-06-07-1]) も想起される.ほかには,長期間にわたる言語変化の drift (駆流)も,言語有機体説と調和しやすいことを指摘しておこう(特に[2012-09-09-1]の記事「#1231. drift 言語変化観の引用を4点」を参照).

言語が生きているという比喩をあえて用いるとしても,言語が自ら生きているのではなく,話者(集団)によって生かされているととらえるほうがよいと考える.話者(集団)がいなければ言語そのものが存在し得ないことは自明だからである.しかし,言語変化という観点から言語と話者に注目すると,両者の関係は必ずしも自明でなく,不思議な機構が働いているようにも思われる([2013-07-24-1]の記事「#1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language?」を参照).

現代の言語学者のほとんどは「言語は植物である」という比喩を過去のアイデアとして葬り去っているが,一般にはいまだ広く流布している.非常に根強い神話である.

・ Aitchison, Jean. "Metaphors, Models and Language Change." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 39--53.

2013-07-24 Wed

■ #1549. Why does language change? or Why do speakers change their language? [language_change][causation][invisible_hand][teleology][drift][functionalism]

「なぜ言語は変化するのか」と「なぜ話者は言語を変化させるのか」とは,おおいに異なる問いである.発問に先立つ前提が異なっている.

Why does language change? という問いでは,言語が主語(主体)となってあたかも生物のように自らが発展してゆくといった言語有機体説 (organicism) や言語発達説 (ontogenesis) の前提が示唆されている.言語の変化が必然で不可避 (necessity) であることをも前提としている.一方,Why do speakers change their language? という問いでは,話者が主語(主体)であり,話者が自由意志 (free will) によって言語を変化させるのだという機械主義 (mechanism) や技巧 (artisanship) の前提が示唆される.

どちらが正しい発問かといえば,Keller (8--9) に語らせれば,どちらも言語変化を正しく問うていない.というのは,言語変化は集合的な現象 (collective phenomena) だからである.この集団的な現象を統御しているのは目的論 (teleology) ではなく,「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) の原理である,と Keller は主張する.

見えざる手については「#10. 言語は人工か自然か?」 ([2009-05-09-1]) で話題にしたが,この理論の源泉は Bernard de Mandeville (1670--1733) による The Fable of the Bees: Private Vices, Public Benefits (1714) に求めることができる.要点として,Keller から3点を引用しよう.

・ the insight that there are social phenomena which result from individuals' actions without being intended by them (35)

・ An invisible-hand explanation is a conjectural story of a phenomenon which is the result of human actions, but not the execution of any human design (38)

・ a language is the unintentional collective result of intentional actions by individuals (53)

これを言語変化に当てはめると,個々の話者の言語活動における選択は意図的だが,その結果として起こる言語変化は最初から意図されていたものではないということになる.入力は意図的だが出力は非意図的となると,その間にどのようなブラックボックスがはさまっているのかが問題となるが,このブラックボックスのことを見えざる手と呼んでいるのである.個々の話者の意図的な言語行動が無数に集まって,見えざる手というブラックボックスに入ってゆくと,当初個々の話者には思いもよらなかった結果が出てくる.この結果が,言語変化ということになる.ここから,Keller (89) は言語変化の長期的な機能主義性を指摘している.

As an invisible-hand explanation of a linguistic phenomenon always starts with the motives of the speakers and 'projects' the phenomenon itself as the macro-structural effect of the choices made, it is necessarily functionalistic, although in a 'refracted' way.

言語変化に至る過程のスタート地点では話者が主体となっているが,途中で見えざる手のトンネルをくぐり抜けると,いつのまにか主体が言語に切り替わっている.このような言語変化観をもつ者からみれば,Why does language change? も Why do speakers change their language? も適切な質問でないことは明らかだろう.どちらも違っているともいえるし,どちらも当たっているともいえる.見えざる手の前提が欠落している,ということになろう.

・ Keller, Rudi. On Language Change: The Invisible Hand in Language. Trans. Brigitte Nerlich. London and New York: Routledge, 1994.

2013-02-28 Thu

■ #1403. drift を合理的に説明する Ritt の試み [drift][teleology][unidirectionality][causation][language_change][functionalism]

昨日の記事「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) で取り上げた論文で,Ritt は歴史言語学上の重要な問題である drift (駆流)にまとわりつく謎めいたオーラを取り除こうとしている.drift の問題は「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]) と「#686. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (2)」 ([2011-03-14-1]) でも取り上げたが,次のように提示することができる.話者個人は自らの人生の期間を超えて言語変化を継続させようとする動機づけなどもっていないはずなのに,なぜ世代を超えて伝承されているとしか思えない言語変化があるのか.あたかも言語そのものが話者を超越したところで生命をもっているかのような振る舞いを見せるのはなぜか.この問題を Ritt (215) のことばで示すと,次のようになる.

[S]ince individual speakers are normally not aware of the long-term histories of their languages and have no reason to be interested in them at all, it is difficult to see why they should be motivated to adjust their behaviour in communication or language acquisition to make the development of their language conform to any long-term trend.

この謎に対し,Ritt (215) は言語と話者についての3つの前提を理解することで解決できると述べる.

First, . . . the case can be made that even though whole language systems do not represent historical objects, their constituents do, because they are transmitted faithfully enough among speakers and thereby establish populations and lineages of constituent types which persist in time. Secondly, when speakers make choices among different variants of a linguistic constituent, they are not completely free. Instead their choice is always limited (a) by universal constraints on human physiology and (b) by socio-historical contingencies such as the relative prestige of different constituent variants. Since it would be against the self-interests of individual speakers to resist them, their choices can be expected to reflect physiological and social constraints more or less automatically. Thirdly, a speaker never chooses among isolated pairs of constituent variants. Instead constituent choice always occurs in the context of actual discourse, where any constituent of a linguistic system is always used and expressed in combination with others.

そして驚くべきことに,話者は上記の前提に基づく言語行動において,生理的,社会的な機械として機能しているにすぎないという見解が示される (215--16) .

In such interactions between constituents the role of speakers will be restricted to responding --- unconsciously and more or less automatically --- to physiological and social constraints on their communicative behaviour. In other words, speakers will not figure as autonomous, active and whimsical agents of change, but merely provide the mechanics through which linguistic constituents interact with each other.

このモデルによれば,話者は,個々の言語項目が相互に組み立てているネットワークのなかを動き回る,生理的よび社会的な機能を付与された媒質ということになる.話者が言語変化の主体ではなく媒介であるという提言は,きわめて controversial だろう.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

2013-02-27 Wed

■ #1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由 [drift][causation][language_change][vowel][diphthong][consonant][degemination][phoneme][phonetics][gvs][meosl][functionalism][isochrony][functional_load][homorganic_lengthening]

「#1231. drift 言語変化観の引用を4点」 ([2012-09-09-1]) の記事で,Ritt の論文に触れた.この論文では標題に掲げた問題が考察されるが,筆者の態度はきわめて合理主義的で機能主義的である.

Ritt は,中英語以来の Homorganic Lengthening, Middle English Open Syllable Lengthening (MEOSL), Great Vowel Shift を始めとする長母音化や2重母音化,また連動して生じてきた母音の量の対立の明確化など,種々の母音にまつわる変化を「母音の強化」 (strengthening of vowels) と一括した.それに対して,子音の量の対立の解消,子音の母音化,子音の消失などの種々の子音にまつわる変化を「子音の弱化」 (weakening of consonants) と一括した.直近千年にわたる英語音韻史は母音の強化と子音の弱化に特徴づけられるとしながら,その背景にある原因を合理的に説明しようと試みた.このような歴史的な潮流はしばしば drift (駆流)として言及され,歴史言語学においてその原動力は最大の謎の1つとなっているが,Ritt は意外なところに解を見いだそうとする.それは,英語に長いあいだ根付いてきた "rhythmic isochrony" と "fixed lexical stress on major class lexical items" (224) である.

広く知られているように,英語には "rhythmic isochrony" がある.およそ強い音節と弱い音節とが交互に現われる韻脚 (foot stress) の各々が,およそ同じ長さをもって発音されるという性質だ.これにより,多くの音節が含まれる韻脚では各音節は素早く短く発音され,逆に音節数が少ない韻脚では各音節はゆっくり長く発音される.さらに,英語には "fixed lexical stress on major class lexical items" という強勢の置かれる位置に関する強い制限があり,強勢音節は自らの卓越を明確に主張する必要に迫られる.さて,この2つの原則により,強勢音節に置かれる同じ音素でも統語的な位置によって長さは変わることになり,長短の対立が常に機能するとは限らない状態となる.特に英語の子音音素では長短の対立の機能負担量 (functional load) はもともと大きくなかったので,その対立は初期中英語に消失した(子音の弱化).一方,母音音素では長短の対立は機能負担量が大きかったために消失することはなく,むしろ対立を保持し,拡大する方向へと進化した.短母音と長母音の差を明確にするために,前者を弛緩化,後者を緊張化させ,さらに後者から2重母音を発達させて,前者との峻別を図った.2つの原則と,それに端を発した「母音の強化」は,互いに支え合い,堅固なスパイラルとなっていった.これが,標記の問題に対する Ritt の機能主義的な解答である.

狐につままれたような感じがする.多くの疑問が浮かんでくる.そもそも英語ではなぜ rhythmic isochrony がそれほどまでに強固なのだろうか.他の言語における類似する,あるいは相異する drift と比較したときに,同じような理論が通用するのか.音素の機能負担量を理論的ではなく実証的に計る方法はあるのか.ラベルの貼られているような母音変化が,(別の時機ではなく)ある時機に,ある方言において生じるのはなぜか.

Ritt の議論はむしろ多くの問いを呼ぶように思えるが,その真の意義は,先に触れたように,drift を合理的に説明しようとするところにあるのだろうと思う.それはそれで大いに論争の的になるのだが,明日の記事で.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

2013-02-07 Thu

■ #1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」 [language_change][teleology][drift][unidirectionality]

言語変化をどのようにとらえるかという問題については,言語変化観の各記事で扱ってきた.著名な言語(英語)学者 David Crystal (2) の言語変化観をのぞいてみよう.

[L]anguage is changing around you in thousands of tiny different ways. Some sounds are slowly shifting; some words are changing their senses; some grammatical constructions are being used with greater or less frequency; new styles and varieties are constantly being formed and shaped. And everything is happening at different speeds and moving in different directions. The language is in a constant state of multidimensional flux. There is no predictable direction for the changes that are taking place. They are just that: changes. Not changes for the better; nor changes for the worse; just changes, sometimes going one way, sometimes another.

英語にせよ日本語にせよ,この瞬間にも,多くの言語項目が異なる速度で異なる方向へ変化している."multidimensional flux" とは言い得て妙である.また,言語変化に目的論的に定められた方向性 (teleology) はないという見解にも賛成する.一時的にはある方向をもっているに違いないが,恒久的に一定の方向を保ち続けることはないだろう(関連して unidirectionality の各記事を参照).ただし,一時的な方向とはいっても,drift として言及される印欧語族における屈折の衰退のように,数千年という長期にわたる「一時的な」方向もあるにはある.このように何らかの方向があるにせよ,それが良い方向であるとか悪い方向であるとか,価値観を含んだ方向ではないということは認めてよい.Crystal のいうように,"just changes" なのだろう.

「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) および「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) でも同じような議論をしたので,ご参照を.

・ Crystal, David. "Swimming with the Tide in a Sea of Language Change." IATEFL Issues 149 (1999): 2--4.

2012-10-30 Tue

■ #1282. コセリウによる3種類の異なる言語変化の原因 [language_change][causation][invisible_hand][drift][typology][uniformitarian_principle][grammaticalisation]

なぜ言語は変化するか.英語史,歴史言語学を研究している私の抱いている究極の問いの1つである.これまでも,主として理論的な観点から,causation の各記事で取り上げてきた問題である.Coseriu, E. (Sincronía, Diacronía e Historia. Investigaciones y estudios. Seri Filología y lingüística 2. Montevideo: Revista de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias, 1958. p. 37.) によれば,言語変化の原因を問う際には,異なる3種類の原因を区別すべきであるという.Coseriu の原書をもたないので,Weinreich et al. (99--100fn) より趣旨を要約する.

1つ目は "the rational problem of why languages changes of necessity" である.言語はなぜ変わらなければならないのか,変わる必要があるのか,という哲学的な問いだ.この観点からの言語変化論者としては,Keller が思い浮かぶ.言語変化には「見えざる手」 (invisible_hand) が関与しているという説である.言語変化はある種の方向をもって進行すると考える「駆流」 (drift も,ここに含まれるだろうか.

2つ目は "the general problem of conditions under which particular changes usually appear in languages" である.言語変化には,異なる言語,異なる時代において共通して見られるものがある.これは偶然とは考えにくく,背景に一般的な原因,あるいはより控えめな表現でいえば conditioning factors が作用していると考えるのが妥当である.生理的,心理的,社会的な要因を含めた広い意味での言語学的な諸条件が,ある特定の変化を引き起こす傾向があるということは受け入れられている.言語類型論や言語普遍性の議論,uniformitarian_principle (斉一論の原則),grammaticalisation などが,ここに属するだろうか.

3つ目は "the historical problem of accounting for concrete changes that have taken place" である.これは,一般的に言語変化を論じるのとは別に,実際に生じた(生じている)言語変化の個々の事例を説明しようとする試みのことである.英語史の研究では,通常,具体的な言語変化の事例を扱う.古英語では名詞複数形を形成するのに数種類の方法があったが,なぜ中英語以降には事実上 -s のみとなったのか.なぜ名前動後という強勢パターンが16世紀後半に現われ始めたのか.なぜ大母音推移が生じたのか,等々.具体的な言語変化の歴史性,単発性,個別性を強調する視点といってよいだろう.

Coseriu は,言語学は,この3種類の問題を混同してはならないと注意を喚起している.

・ Weinreich, Uriel, William Labov, and Marvin I. Herzog. "Empirical Foundations for a Theory of Language Change." Directions for Historical Linguistics. Ed. W. P. Lehmann and Yakov Malkiel. U of Texas P, 1968. 95--188.

2012-09-09 Sun

■ #1231. drift 言語変化観の引用を4点 [drift][causation][language_change][popular_passage]

言語変化の原動力として,drift を想定する言語論者は,今もって少なくない.drift の問題として,特に「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]) と「#686. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (2)」 ([2011-03-14-1]) の記事で議論したが,近年,新たな視点からこの問題に迫っているのがウィーン大学の Ritt である.Ritt の言語変化観は刺激的だと思っているが,彼の最近の論文 (p. 131) で,drift を支持する研究者からの重要な引用が4点ほどなされていたので,それを再現したい(便宜のため,引用元の典拠は展開しておく).

Languages . . . came into being, grew and developed according to definite laws, and now, in turn, age and die off . . . (Schleicher, August. Die Darwinsche Theorie und die Sprachwissenschaft: offenes Sendschreiben an Herrn Dr. Ernst Häckel. Weimar: H. Böhlau, 1873. Page 16.)

Language moves down time in a current of its own making. It has a drift. (Sapir, Edward. Language: An Introduction to the Study of Speech. New York: Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1921. Page 151.)

A living language is not just a collection of autonomous parts, but, as Sapir (1921) stressed, a harmonious and self-contained whole, massively resistant to change from without, which evolves according to an enigmatic, but unmistakably real, inner plan. (Donegan, Patricia Jane and David Stampe. "Rhythm and the Holistic Organization of Language Structure." Papers from the Parasession on the Interplay of Phonology, Morphology and Syntax. Eds. John F. Richardson, Mitchell Marks, and Amy Chukerman. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society, 1983. 337--53. Page 1.)

languages . . . are objects whose primary mode of existence is in time . . . which ought to be viewed as potentially having extended (trans-individual, transgenerational) 'lives of their own'. (Lass, Roger. "Language, Speakers, History and Drift." Explanation and Linguistic Change. Eds. W. F. Koopman, Frederike van der Leek, Olga Fischer, and Roger Eaton. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 1987. 151--76. Pages 156--57.).

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

2012-07-06 Fri

■ #1166. 副詞派生接尾辞 -ly の発達の謎 [adverb][flat_adverb][suffix][indo-european][inflection][drift][-ly]

Fortson (132--33) によれば,印欧祖語には,英語の -ly に相当するような,形容詞から副詞を派生させる専門の語尾は存在しなかった.むしろ,名詞や形容詞の屈折形を用いることで,副詞的な機能を得ており,この方法はすべての娘言語で広く見られる.しかし,このようにして派生された副詞は比較的新しいものであり,印欧祖語にまで遡るものはきわめて少ないという.形容詞から副詞的機能を生み出す屈折形の典型は中性の主格・対格の単数であり,例えば「大きな」に対する「大きく,大いに」は印欧祖語で *meĝh2 が再建されている.これは,Hitt. mēk, Ved. máhi, Gk. méga, ON mjǫok に相当する.古英語でも,形容詞を中性対格単数に屈折させた efen "even", full "full", (ge)fyrn "ancient", gehwǣde "little", genōg "enough", hēah "high", lȳtel "little" は副詞として機能する (Campbell 276) .

この典型から外れたものとして,ほかにも,主格から作られた Lat. rursus "back(wards)",奪格から作られた Lat. meritō "deservedly",具格から作られた Lat. quī "how" などがあり,古英語でも,属格を用いる ealles "entirely", micles "much",与格を用いる ǣne "alone", lȳtle "little" などがある (Campbell 276) .取り得る格形は様々だが,印欧諸語における形容詞由来の副詞は,基本的に屈折による形成と考えられる.

この伝統的な副詞派生はゲルマン諸語にも継承された.屈折が多少なりとも水平化し,主格などとの形態的な区別がつけられなくなった後でも,特別な処置は施されず,「形容詞=副詞」体制で持ちこたえた.英語においては flat adverb がその例である.しかし,英語では,flat adverb とは別に,形容詞と副詞を形態的に区別せんとばかりに -ly が発達してきた.したがって,英語は,この点でゲルマン諸語のなかでは特異な振る舞いを示しているように思われる.

ただし,ゲルマン語派の外を見れば,[2012-03-01-1]の記事「#1039. 「心」と -ment」で取り上げたように,ロマンス語派でも副詞派生接尾辞は発達している.したがって,英語が特異であると断定することは必ずしもできないかもしれない.

関連して,Killie (119) は,英語の現在分詞形容詞が -ly を取るようになった歴史的経緯を調査した論文の冒頭で,英語のこの振る舞いを,ノルウェー語,スウェーデン語,ドイツ語などには見られない特異な現象であると示唆している.しかし,なぜ英語で -ly のような副詞派生接尾辞が発達したのかについては,その論文でも触れられていない.ただし,Killie (127) は,英語史上の一種の drift としての "adverbialization process" に言及しており,-ly 副詞の発達はその一環であると理解しているようだ.

・ Fortson IV, Benjamin W. Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2004.

・ Campbell, A. Old English Grammar. Oxford: OUP, 1959.

・ Killie, Kristin. "The Spread of -ly to Present Participles." Advances in English Historical Linguistics. Ed. Jacek Fisiak and Marcin Krygier. Mouton de Gruyter: Berlin and New York: 1998. 119--34.

2011-08-18 Thu

■ #843. 言語変化の予言の根拠 [prediction_of_language_change][language_change][drift][acquisition]

中尾 (2) では,言語変化の予言とその根拠について次のように述べられている.

一般にことばの変化についての予言は,

(i) 現在進行中の変化および方向,

(ii) 過去において実際に起こった歴史的変化および方向,

(iii) 同系言語にみられる変化,

(iv) 幼児の言語習得,

などに基づいて行われる.

(i) から (iv) にかけて,具体から抽象へ,特殊から一般へと基準の普遍性が高くなっている点が注目に値する.(i) は当該言語の現在における変化の事実,(ii) は当該言語の過去に生じた変化の事実,(iii) は同系言語の現在と過去の変化の事実( drift の議論などが関与する),(iv) は言語そのものではなくヒトの言語習得 (language acquisition) の示す特性(過去も現在も未来も不変との仮定で)にそれぞれ相当する.

しかし,(iii) の後に,同系・非同系言語の全体,つまり人類言語の総体において現在および過去に生じた変化の事実という参照点を加えてもよいのではないか.端的にいえば,通言語的な言語変化の類型論 (typology of language change) という視点である.「言語変化の予言の根拠」の改訂版を図示すると以下のようになるだろうか.

具体・特殊 | | (1) 当該言語の言語変化(現在) | | (2) 当該言語の言語変化(過去) | | (3) 同系言語の言語変化(現在・過去) | | (4) 人類言語の言語変化(現在・過去) | | (5) 言語習得と言語変化(現在・過去) ↓ 抽象・一般

これらの手がかりを参考に,当該言語が今後どのように変化して行くのか,その未来の姿はどのようなものになるだろうかについて予言がなされることになる.ただし,言語変化を予言するという行為については,言語学者の間にも様々な考え方がある.例えば,Sapir (Chapters 7--8) は積極的に言語変化の予言をしているが,一方で Bauer (21, 25) は予言がいかに危険であるかを説いている.

上で引用した中尾 (2) は,次のように述べている.

ことばの変化は,まったく同じ条件が整ったからといって必ず生起するとは限らない.その意味で,ことばの変化は自然科学の法則 (law) とはちがい,傾向 (trend, tendency) を示すにすぎない.

結局,変化についての予言,記述などは,「ことばの変化を引き起こす要因は何か」という基本的な問題を解明する努力へ通じるものである.

この文章から,著者は言語変化を予言するという行為の価値は,それが当たるかどうかという予言としての精度にあるのではなく,言語変化の原因を明らかにしようとする営みである点にあると考えていることが分かる.Bauer の批判的態度もよく分かるのだが,基本的には中尾の立場に同意したい.

・ 中尾 俊夫 著,児馬 修・寺島 迪子 編 『変化する英語』 ひつじ書房,2003年.

・ Sapir, Edward. Language. New York: Hartcourt, 1921.

・ Bauer, Laurie. Watching English Change: An Introduction to the Study of Linguistic Change in Standard Englishes in the Twentieth Century. Harlow: Longman, 1994.

2011-08-11 Thu

■ #836. 機能負担量と言語変化 [functionalism][language_change][systemic_regulation][terminology][phonology][drift][minimal_pair][functional_load]

昨日の記事「機能主義的な言語変化観への批判」([2011-08-10-1]) で触れた,機能負担量 (functional load or functional yield) について.機能負担量とはある音韻特徴がもつ弁別機能の高さのことで,多くの弁別に役立っているほど機能負担量が高いとみなされる.

例えば,英語では音素 /p/ と /b/ の対立は,非常に多くの語の弁別に用いられる.別の言い方をすれば,多くの最小対 (minimal pair) を産する (ex. pay--bay, rip--rib ) .したがって,/p/ と /b/ の対立の機能負担量は大きい.しかし,/ʃ/ と /ʒ/ の対立は,mesher--measure などの最小対を生み出してはいるが,それほど多くの語の弁別には役立っていない.同様に,/θ/ と /ð/ の対立も,thigh--thy などの最小対を説明するが,機能負担量は小さいと考えられる.

機能負担量という概念は,上記のような個別音素の対立ばかりではなく,より抽象的な弁別特徴の有無の対立についても考えることができる.例えば,英語において声の有無 (voicing) という対立は,すべての破裂音と /h/ 以外の摩擦音について見られる対立であり,頻繁に使い回されているので,その機能負担量は大きい.

では,機能負担量と言語変化がどのように結び着くというのだろうか.機能主義的な考え方によると,多くの語の弁別に貢献している声の有無のような機能負担量の大きい対立が,もし解消されてしまうとすると,体系に及ぼす影響が大きい.したがって,機能負担量の大きい対立は変化しにくい,という議論が成り立つ.反対に,機能負担量の小さい対立は,他の要因によって変化を迫られれば,それほどの抵抗を示さない.この論でゆくと,/θ/ と /ð/ の対立は,機能負担量が小さいため,ややもすれば失われないとも限らない不安定な対立ではあるが,一方でより抽象的な次元で声の有無という盤石な,機能負担量の大きい対立によって支えられているために,それほど容易には解消されないということになろうか.機能主義論者の主張する,言語体系に内在するとされる「対称性 (symmetry) の指向」とも密接に関わることが分かるだろう.

体系的な対立を守るために,あるいは対立の解消を避けるために変化が抑制されるという「予防」の考え方は,すぐれて機能主義的な視点である.しかし,話者(集団)は体系の崩壊を避ける「予防」についてどのように意識しうるのか.話者(集団)は日常の言語行動で無意識に「予防」行為を行なっていると考えるべきなのか.これは,[2011-03-13-1]の記事「なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」で見たものと同類の議論である.

・ Schendl, Herbert. Historical Linguistics. Oxford: OUP, 2001.

2011-07-09 Sat

■ #803. 名前動後の通時的拡大 [stress][diatone][drift][speed_of_change][lexical_diffusion]

「名前動後」の起源について[2009-11-01-1], [2009-11-02-1], [2011-07-07-1], [2011-07-08-1]の記事で議論してきたが,その通時的拡大の事実についてはまだ紹介していなかった.

Sherman は,SOED と Web3 の両辞書に重複して確認される名詞と動詞が同綴り (homograph) である語を取り出し,そのなかで強勢交替を示す語を分別した.音節数別に内訳を示すと,以下の通りとなる (Sherman 51) .

| potential diatonics | actual diatonics | |

|---|---|---|

| disyllabic N-V pairs | 1,315 | 150 (11.41%) |

| trisyllabic | 442 | 70 (15.84%) |

| polysyllabic | 1,757 | 220 (12.52%) |

対象を2音節語に限定すると,1315語あるが,そのなかで強勢交替を示すものは実は150語 (11.41%) にすぎない.強勢交替を示さない1165語について見てみると,名詞・動詞ともに強勢が第2音節に置かれている oxytone は215語,第1音節に置かれている paroxytone は950語で後者が圧倒している.「名前動後」は現実以上に話題として強調されすぎており,実際には「名前動前」が支配的だという結果が出た.

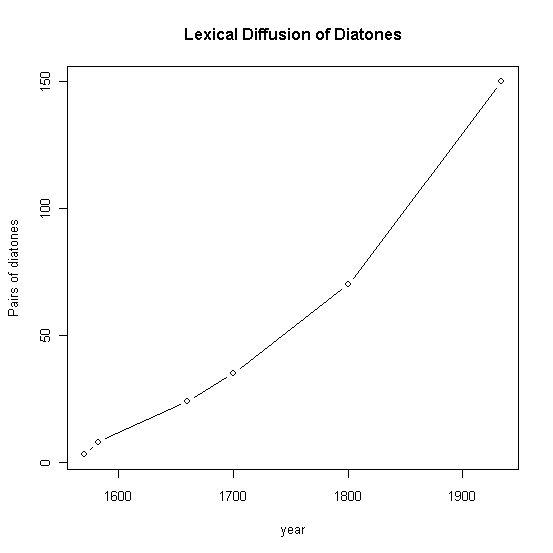

近代期以降の通時的観察によると,「名後動後」という oxytone の語が,名詞について強勢を前寄りに繰り上げるという方向での変化が多いという (Sherman 53, 55) .「名前動後」の diatone を表わす2音節語は近代英語期からゆっくりと確実に分布を広げてきており,20世紀半ばまでに150語に達している.以下の「名前動後」の通時的推移を表わすグラフは,Sherman (54) のグラフに基づいて再作成したものである(ただし,19世紀と20世紀についての数値は "tentative" とされている),

Sherman の研究は,語彙拡散 (Lexical Diffusion) の例を提供していると考えられるかもしれない重要な研究である.この曲線が,語彙拡散の予想するS字曲線に沿っているのかどうかはまだ判然としないが,この数百年の潮流を観察すれば,今後も名前動後が少しずつ増えてゆくだろうことは容易に予想される.

この論文は何度か読んでいるが,研究の計画・手法,使用する資料,事実の提示法,論旨にいたるまで実によくできており,スリル感をもって読ませる好論である.

・ Sherman, D. "Noun-Verb Stress Alternation: An Example of the Lexical Diffusion of Sound Change in English." Linguistics 159 (1975): 43--71.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow