2023-05-13 Sat

■ #5129. 進行形に関する「ケルト語仮説」 [celtic][borrowing][syntax][contact][substratum_theory][celtic_hypothesis][progressive][verb][irish_english][aspect]

「#4595. 強調構文に関する「ケルト語仮説」」 ([2021-11-25-1]) で参照した Filppula and Klemola の論文を再読している.同論文では,英語における be + -ing の「進行形」 (progressive form) の発達(その時期は中英語期とされる)も基層のケルト語の影響によるものではないかという「ケルト語仮説」 (celtic_hypothesis) が唱えられている.

まず興味深い事実として,現代のケルト圏で行なわれている英語諸変種では,標準英語よりも広範に進行形が用いられるという.具体的には Irish English, Welsh English, Hebridean English, Manx English において,標準的には進行形を取りにくいとされる状態動詞がしばしば進行形で用いられること,動作動詞を進行形にすることにより習慣相が示されること,would や used (to) に進行形が後続し,習慣的行動が表わされること,do や will に進行形が後続する用法がみられることが報告されている.Filppula and Klemola (212--14) より,それぞれの例文を示そう.

・ There was a lot about fairies long ago [...] but I'm thinkin' that most of 'em are vanished.

・ I remember my granfather and old people that lived down the road here, they be all walking over to the chapel of a Sunday afternoon and they be going again at night.

・ But they, I heard my father and uncle saying they used be dancing there long ago, like, you know.

・ Yeah, that's, that's the camp. Military camp they call it [...] They do be shooting there couple of times a week or so.

これらは現代のケルト変種の英語に見られる進行形の多用という現象を示すものであり,事実として受け入れられる.しかし,ケルト語仮説の要点は,中英語における進行形の発達そのものが基層のケルト語の影響によるものだということだ.前者と後者は注目している時代も側面も異なっていることに注意したい.それでも,Filppula and Klemola (218--19) は,次の5つの論点を挙げながら,ケルト語仮説を支持する(引用中の PF は "progressive forms" を指す).

(i) Of all the suggested parallels to the English PF, the Celtic (Brythonic) ones are clearly the closest, and hence, the most plausible ones, whether one think of the OE periphrastic constructions or those established in the ME and modern periods, involving the -ing form of verbs. This fact has not been given due weight in some of the earlier work on this subject.

(ii) The chronological precedence of the Celtic constructions is beyond any reasonable doubt, which also enhances the probability of contact influence from Celtic on English.

(iii) The socio-historical circumstances of the Celtic-English interface cannot have constituted an obstacle to Celtic substratum influences in the area of grammar, as has traditionally been argued especially on the basis of the research (and some of the earlier, too) has shown that the language shift situation in the centuries following the settlement of the Germanic tribes in Britain was most conductive to such influences. Again, this aspect has been ignored or not properly understood in some of the research which has tried to play down the role of Celtic influence in the history of English.

(iv) The Celtic-English contacts in the modern period have resulted in a similar tendency for some regional varieties of English to make extensive use of the PF, which lends indirect support to the Celtic hypothesis with regard to early English.

(v) Continuous tenses tend to be used more in bilingual or formerly Celtic-speaking areas than in other parts of the country . . . .

ケルト語仮説はここ数十年の間に提起され論争の的となってきた.いまだ少数派の仮説にとどまるといってよいが,伝統的な英語史記述に一石を投じ,言語接触の重要性に注目させてくれた点では,学界に貢献していると評価できる.

・ Filppula, Markku and Juhani Klemola. "English in Contact: Celtic and Celtic Englishes." Chapter 107 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1687--1703.

2023-02-28 Tue

■ #5055. 英語史における言語接触 --- 厳選8点(+3点) [contact][loan_word][borrowing][latin][celtic][old_norse][french][dutch][greek][japanese][link]

英語が歴史を通じて多くの言語と接触 (contact) してきたことは,英語史の基本的な知識である.各接触の痕跡は,歴史の途中で消えてしまったものもあるが,現在まで残っているものも多い.痕跡のなかで注目されやすいのは借用語彙だが,文法,発音,書記など語彙以外の部門でも言語接触のインパクトがあり得ることは念頭に置いておきたい.

英語の言語接触の歴史を短く要約するのは至難の業だが,Schneider (334) による厳選8点(時代順に並べられている)が参考になる.

・ continental contacts with Latin, even before the settlement of the British Isles (i.e., roughly between the second and fourth centuries AD);

・ contact with Celts who were the resident population when the Germanic tribes crossed the channel (in the fifth century and thereafter);

・ the impact of Latin through Christianization (beginning in the late sixth and seventh centuries);

・ contact with Scandinavian raiders and later settlers (between the seventh and tenth centuries);

・ the strong exposure to French as the language of political power after 1066;

・ the massive exposure to written Latin during the Renaissance;

・ influences from other European languages beginning in the Early Modern English period; and

・ the impact of colonial contacts and borrowings.

よく選ばれている8点だと思うが,私としてはここに3点ほど付け加えたい.1つは,伝統的な英語史では大きく取り上げられないものの,中英語期以降に長期にわたって継続したオランダ語との接触である.これについては「#4445. なぜ英語史において低地諸語からの影響が過小評価されてきたのか?」 ([2021-06-28-1]) やその関連記事を参照されたい.

2つ目は,上記ではルネサンス期の言語接触としてラテン語(書き言葉)のみが挙げられているが,古典ギリシア語(書き言葉)も考慮したい.ラテン語ほど目立たないのは事実だが,ルネサンス期以降,ギリシア語の英語へのインパクトは大きい.「#516. 直接のギリシア語借用は15世紀から」 ([2010-09-25-1]) および「#4449. ギリシア語の英語語形成へのインパクト」 ([2021-07-02-1]) を参照.

最後に日本語母語話者としてのひいき目であることを認めつつも,主に19世紀後半以降,英語が日本語と意外と濃厚に接触してきた事実を考慮に入れたい.これについては「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース」 ([2015-04-01-1]),「#3872. 英語に借用された主な日本語の借用年代」 ([2019-12-03-1]),「#4140. 英語に借用された日本語の「いつ」と「どのくらい」」 ([2020-08-27-1]) を参照.

Schneider の8点に,この3点を加え,私家版の厳選11点の完成!

・ Schneider, Edgar W. "Perspectives on Language Contact." Chapter 13 of English Historical Linguistics: Approaches and Perspectives. Ed. Laurel J. Brinton. Cambridge: CUP, 332--59.

2023-01-30 Mon

■ #5026. 接尾辞 -age [suffix][french][latin][word_formation][noun][borrowing][loan_word]

-age は名詞を作る接尾辞 (suffix) として一見目立たなそうだが,意外と基本的な単語にも用いられている.例えば percentage, marriage, usage, passage, storage, shortage, mileage, voltage, baggage, postage, luggage, breakage, bondage, anchorage, shrinkage, orphanage 等をみれば頷けるだろう.

語源としては,古典時代以降のラテン語 -agium に遡る場合もあれば,同じく古典時代以降のラテン語の別の語尾 -aticum(古典ラテン語の形容詞語尾 -āticus の中性形より)がフランス語に -age として伝わったものに由来する場合もある.いずれももとより名詞を作る接尾辞として機能していた.

この接尾辞をもつ単語は早くも初期中英語期にフランス語やラテン語から借用されていたが,後期中英語期になると peerage, mockage など英語内部で語形成されたものも現われ,この傾向は近代英語期になるととりわけ強くなった.現代英語においてもある程度の生産性を有する接辞で,1949年には signage などの語が作られている.

この接尾辞の主な意味を語例とともに挙げてみよう.

1. 集合: cellarage, leafage, luggage, surplusage, trackage, wordage

2. 動作・過程: coverage, haulage, stoppage

3. 結果: breakage, shrinkage, usage

4. 率・数量: acreage, dosage, leakage, mileage, outage, slippage

5. 家・場所: orphanage, parsonage, steerage

6. 状態: bondage, marriage, peonage

7. 料金: postage, towage, wharfage

このように -age は英語では原則として名詞を作る接尾辞だが,ラテン語の形容詞語尾 -āticus より機能を受け継ぎ,珍しく形容詞としてフランス語より入ってきた savage という語を挙げておこう.

2022-12-04 Sun

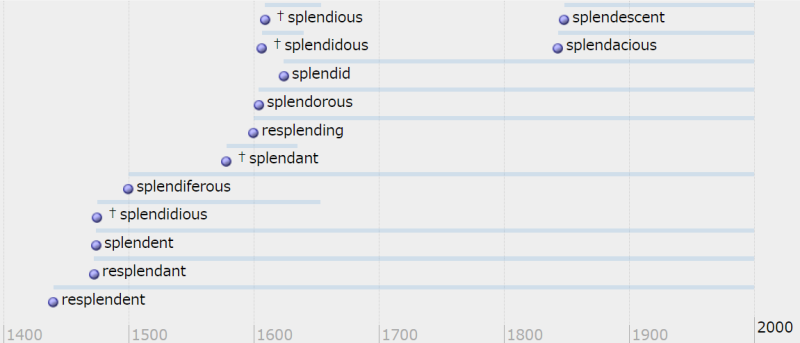

■ #4969. splendid の同根類義語のタイムライン [cognate][synonym][lexicology][inkhorn_term][emode][borrowing][loan_word][renaissance][oed][timeline]

すでに「#3157. 華麗なる splendid の同根類義語」 ([2017-12-18-1]) で取り上げた話題ですが,一ひねり加えてみました.splendid (豪華な,華麗な;立派な;光り輝く)というラテン語の動詞 splendēre "to be bright or shining" に由来する形容詞ですが,英語史上,数々の同根類義語が生み出されてきました.先の記事で触れなかったものも含めて OED で調べた単語を列挙すると,廃語も入れて13語あります.

resplendant, resplendent, resplending, splendacious, †splendant, splendent, splendescent, splendid, †splendidious, †splendidous, splendiferous, †splendious, splendorous

OED に記載のある初出年(および廃語の場合は最終例の年)に基づき,各語の一生をタイムラインにプロットしてみたのが以下の図です.とりわけ16--17世紀に新類義語の登場が集中しています.

ほかに1796年に初出の resplendidly という副詞や1859年に初出の many-splendoured という形容詞など,合わせて考えたい語もあります.いずれにせよ英語による「節操のない」借用(あるいは造語)には驚かされますね.

2022-12-01 Thu

■ #4966. 英語語彙史の潮流と雑感 [lexicology][word_formation][neologism][esl][world_englishes][contact][borrowing][loan_word][link]

英語語彙史を鳥瞰すると,いかにして新語が導入されたてきたかという観点から大きな潮流をつかむことができる.新語導入の方法として,大雑把に (1) 借用 (borrowing) と (2) 語形成 (word_formation) の2種類を考えよう.借用は他言語(方言)から単語を借り入れることである.語形成は既存要素(それが語源的には本来語であれ借用語であれ)をもとにして派生 (derivation),複合 (compounding),品詞転換 (conversion),短縮 (shortening) などの過程を経て新たな単語を作り出すことである.

・ 古英語期:主に語形成による新語導入が主.ただし,ラテン語や古ノルド語からの借用は多少あった.

・ 中英語期:フランス語やラテン語からの新語導入が主.ただし,語形成も継続した.

・ 初期近代英語期:ラテン語やギリシア語からの新語導入が主.ただし,それまでに英語に同化していた既存要素を用いた語形成も少なくない.

・ 後期近代英語期・現代英語期:語形成が主.ただし,世界の諸言語からの借用は継続している.

時代によって借用と語形成のウェイトが変化してきた点が興味深い.大雑把にいえば,古英語期は語形成偏重,次の中英語期は借用偏重,近代英語来以降は両者のバランスがある程度回復してきたとみることができる.それぞれの時代背景には征服,ルネサンス,帝国主義など社会・文化的な出来事が確かに対応している.

しかし,上記はあくまで大雑把な潮流である.借用と語形成のウェイトの変化こそあったが,見方を変えれば,英語史を通じて常に両方法が利用されてきたとみることもできる.また,これはあくまで標準英語の語彙史にみられる潮流であることにも注意を要する.他の英語変種の語彙史を考えるならば,例えばインド英語などの ESL (= English as a Second Language) を念頭に置くならば,近代・現代では現地の諸言語からの語彙のインプットは疑いなく豊富だろう.激しい言語接触の産物ともいえる英語ベースのピジンやクレオールではどうだろうか.逆に言語接触の少ない環境で育まれてきた英語変種の語彙史にも興味が湧く.

英語語彙史に関する話題は hellog でも多く取り上げてきたが,歴史を俯瞰した内容のもののみを以下に示す.

・ 「#873. 現代英語の新語における複合と派生のバランス」 ([2011-09-17-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 「#1956. Hughes の英語史略年表」 ([2014-09-04-1])

・ 「#2966. 英語語彙の世界性 (2)」 ([2017-06-10-1])

・ 「#4130. 英語語彙の多様化と拡大の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes"」 ([2020-08-17-1])

・ 「#4133. OED による英語史概説」 ([2020-08-20-1])

・ 「#4716. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」のダイジェスト「英語語彙の歴史」を終えました --- これにて本当にシリーズ終了」 ([2022-03-26-1])

2022-09-25 Sun

■ #4899. magazine は「火薬庫」だった! [etymology][arabic][french][false_friend][semantic_change][italian][spanish][portuguese][borrowing][loan_word]

英仏語の "false friends" (= "faux amis") の典型例の1つに英語 magazine (雑誌)と仏語 magasin (店)がある.語形上明らかに関係しているように見えるのに意味がまるで違うので,両言語を学習していると面食らってしまうというケースだ(ただし,フランス語にも「雑誌」を意味する magazine という単語はある).

OED により語源をたどってみよう.この単語はもとをたどるとアラビア語で「倉庫」を意味する mákhzan に行き着く.この複数形 makhāˊzin が,まずムーア人のイベリア半島侵入・占拠の結果,スペイン語やポルトガル語に入った.「倉庫」を意味するスペイン語 almacén,ポルトガル語 armazém は,語頭にアラビア語の定冠詞 al-, ar- が付いた形で借用されたものである.スペイン語での初出は1225年と早い.

この単語が,通商ルートを経て,定冠詞部分が取り除かれた形で,1348年にイタリア語に magazzino として,1409年にフランス語に magasin として取り込まれた(1389年の maguesin もあり).そして,英語はフランス語を経由して16世紀後半に「倉庫」を意味するこの単語を受け取った.初出は1583年で,中東に出かけていたイギリス商人の手紙のなかで Magosine という綴字で現われている.

1583 J. Newbery Let. in Purchas Pilgrims (1625) II. 1643 That the Bashaw, neither any other Officer shall meddle with the goods, but that it may be kept in a Magosine.

しかし,英語に入った早い段階から,ただの「倉庫」ではなく「武器の倉庫;火薬庫」などの軍事的意味が発達しており,さらに倉庫に格納される「貯蔵物」そのものをも意味するようになった.

次の意味変化もじきに起こった.1639年に軍事関係書のタイトルとして,つまり「専門書」ほどの意味で "Animadversions of Warre; or, a Militarie Magazine of the trvest rvles..for the Managing of Warre." と用いられたのである.「軍事知識の倉庫」ほどのつもりなのだろう.

そして,この約1世紀後,ついに私たちの知る「雑誌」の意味が初出する.1731年に雑誌のタイトルとして "The Gentleman's magazine; or, Trader's monthly intelligencer." が確認される.「雑誌」の意味の発達は英語独自のものであり,これがフランス語へ1650年に magasin として,1776年に magazine として取り込まれた.ちなみに,フランス語での「店」の意味はフランス語での独自の発達のようだ.

英仏語の間を行ったり来たりして,さらに各言語で独自の意味変化を遂げるなどして,今ではややこしい状況になっている.しかし,「雑誌」にせよ「店」にせよ,軍事色の濃い,きな臭いところに端を発するとは,調べてみるまでまったく知らなかった.驚きである.

2022-09-17 Sat

■ #4891. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第19回「なぜ単語ごとにアクセントの位置が決まっているの?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][stress][prosody][french][latin][germanic][gsr][rsr][contact][borrowing][lexicology][hellog_entry_set]

『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の10月号が発売となりました.連載「歴史で謎解き 英語のソボクな疑問」の第19回は「なぜ単語ごとにアクセントの位置が決まっているの?」です.

英単語のアクセント問題は厄介です.単語ごとにアクセント位置が決まっていますが,そこには100%の規則がないからです.完全な規則がないというだけで,ある程度予測できるというのも事実なのですが,やはり一筋縄ではいきません.

例えば,以前,学生より「nature と mature は1文字違いですが,なんで発音がこんなに異なるのですか?」という興味深い疑問を受けたことがあります.これを受けて hellog で「#3652. nature と mature は1文字違いですが,なんで発音がこんなに異なるのですか?」 ([2019-04-27-1]) の記事を書いていますが,この事例はとてもおもしろいので今回の連載記事のなかでも取り上げた次第です.

英単語の厄介なアクセント問題の起源はノルマン征服です.それ以前の古英語では,アクセントの位置は原則として第1音節に固定で,明確な規則がありました.しかし,ノルマン征服に始まる中英語期,そして続く近代英語期にかけて,フランス語やラテン語から大量の単語が借用されてきました.これらの借用語は,原語の特徴が引き継がれて,必ずしも第1音節にアクセントをもたないものが多かったため,これにより英語のアクセント体系は混乱に陥ることになりました.

連載記事では,この辺りの事情を易しくかみ砕いて解説しました.ぜひ10月号テキストを手に取っていただければと思います.

英語のアクセント位置についての話題は,hellog よりこちらの記事セットおよび stress の各記事をお読みください.

2022-08-15 Mon

■ #4858. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第18回「なぜ英語には類義語が多いの?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][lexicology][synonym][loan_word][borrowing][french][latin][lexical_stratification][contact][hellog_entry_set][japanese]

昨日『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の9月号が発売となりました.連載「歴史で謎解き 英語のソボクな疑問」の第18回は「なぜ英語には類義語が多いの?」です.

英語には ask -- inquire -- interrogate のような類義語が多く見られます.多くの場合,語彙の学習は暗記に尽きるというのは事実ですので,類義語が多いというのは英語学習上の大きな障壁となります.本当は英語に限った話しではなく,日本語でも「尋ねる」「質問する」「尋問する」など類義語には事欠かないわけなので,どっこいどっこいではあるのですが,現実的には英語学習者にとって高いハードルにはちがいありません.

英語に(そして実は日本語にも)類義語が多いのは,歴史を通じて様々な言語と接触してきたからです.英語にとってとりわけ重要な接触相手はフランス語とラテン語でした.英語は,ある意味を表わす語をすでに自言語にもっていたにもかかわらず,同義のフランス語単語やラテン語単語を借用してきたという経緯があります.結果として,類義語が積み重ねられ,地層のように層状となって今に残っているのです.この語彙の地層は,典型的に下から上へ「本来の英語」「フランス語」「ラテン語」と3層に積み上げられてきたので,これを英語語彙の「3層構造」と呼んでいます.

3層構造については,hellog でも繰り返し取り上げてきました.こちらの記事セットおよび lexical_stratification の各記事をお読みください.

雑誌の連載記事では,この話題を中高生にも分かるように易しく解説しています.ぜひ手に取っていただければと思います.

2022-07-08 Fri

■ #4820. 古ノルド語は英語史上もっとも重要な言語 [youtube][notice][old_norse][contact][loan_word][borrowing][voicy][heldio][link]

一昨日,YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の第38弾が公開されました.「え?それも外来語? 英語ネイティヴたちも(たぶん)知らない借用語たち」です.

今回は古ノルド語 (Old Norse) という言語に注目しましたが,一般にはあまり知られていないかと思います.知っている方は,おそらく英語史を通じて知ったというケースが多いのではないでしょうか.英語史において古ノルド語は実は重要キャラです.歴史上,英語に多大な影響を及ぼしてきた言語であり,私見では英語史上もっとも重要な言語です.

そもそも古ノルド語という言語は何なのでしょうか.現在の北欧諸語(デンマーク語,スウェーデン語,ノルウェー語,アイスランド語など)の祖先です.今から千年ほど前に北欧のヴァイキングたちが話していた言語とイメージしてください.北ゲルマン語派に属し,西ゲルマン語派に属する英語とは,それなりに近い関係にあります.

古ノルド語を母語とする北欧のヴァイキングたちは,8世紀半ばから11世紀にかけてブリテン島を侵略しました.彼らはやがてイングランド北東部に定住し,先住の英語話者と深く交わりました.そのとき,言語的にも深く交わることになりました.結果として,英語に古ノルド語の要素が大量に流入することになったのです.

YouTube では,take, get, give, want, die, egg, bread, though, both,they など,英語語彙の核心に入り込んだ古ノルド語由来の単語に注目しました.しかし,古ノルド語の言語的影響の範囲は,語彙にとどまらず,語法や文法にまで及んでいるのです.英語史上きわめて希有なことです.

この hellog では,古ノルド語と英語の言語接触に関する話題は頻繁に取り上げてきました.関心をもった方は old_norse の記事群をお読みください.また,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」でも様々に話してきました.以下,とりわけ重要な記事・放送にリンクを張っておきますので,ぜひご訪問ください.

[ hellog 記事 ]

・ 「#3988. 講座「英語の歴史と語源」の第6回「ヴァイキングの侵攻」を終えました」 ([2020-03-28-1])

・ 「#2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性」 ([2016-07-04-1])

・ 「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1])

・ 「#2693. 古ノルド語借用語の統計」 ([2016-09-10-1])

・ 「#3982. 古ノルド語借用語の音韻的特徴」 ([2020-03-22-1])

・ 「#170. guest と host」 ([2009-10-14-1])

・ 「#827. she の語源説」 ([2011-08-02-1])

・ 「#3999. want の英語史 --- 語源と意味変化」 ([2020-04-08-1])

・ 「#4000. want の英語史 --- 意味変化と語義蓄積」 ([2020-04-09-1])

・ 「#818. イングランドに残る古ノルド語地名」 ([2011-07-24-1])

・ 「#1938. 連結形 -by による地名形成は古ノルド語のものか?」 ([2014-08-17-1])

・ 「#1937. 連結形 -son による父称は古ノルド語由来」 ([2014-08-16-1])

・ 「#1253. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目」 ([2012-10-01-1])

・ 「#3987. 古ノルド語の影響があり得る言語項目 (2)」 ([2020-03-27-1])

・ 「#1167. 言語接触は平時ではなく戦時にこそ激しい」 ([2012-07-07-1])

・ 「#1170. 古ノルド語との言語接触と屈折の衰退」 ([2012-07-10-1])

・ 「#1179. 古ノルド語との接触と「弱い絆」」 ([2012-07-19-1])

・ 「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1])

・ 「#1183. 古ノルド語の影響の正当な評価を目指して」 ([2012-07-23-1])

・ 「#3986. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の状況は多様で複雑だった」 ([2020-03-26-1])

・ 「#4454. 英語とイングランドはヴァイキングに2度襲われた」 ([2021-07-07-1])

・ 「#1149. The Aldbrough Sundial」 ([2012-06-19-1])

・ 「#3001. なぜ古英語は古ノルド語に置換されなかったのか?」 ([2017-07-15-1])

・ 「#3972. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か?」 ([2020-03-12-1])

・ 「#2591. 古ノルド語はいつまでイングランドで使われていたか」 ([2016-05-31-1])

・ 「#3969. ラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語が英語に及ぼした影響を比較する」 ([2020-03-09-1])

・ 「#4577. 英語と古ノルド語,ローマンケルト語とフランク語」 ([2021-11-07-1])

・ 「#3979. 古英語期に文証される古ノルド語からの借用語のサンプル」 ([2020-03-19-1])

・ 「#2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期」 ([2017-03-05-1])

・ 「#3263. なぜ古ノルド語からの借用語の多くが中英語期に初出するのか?」 ([2018-04-03-1])

・ 「#59. 英語史における古ノルド語の意義を教わった!」 ([2009-06-26-1])

[ heldio 放送 ]

・ 「#179. 和田忍先生との対談:ヴァイキングの活動と英語文献作成の関係」 (2021/11/26)

・ 「#180. 和田忍先生との対談2:ヴァイキングと英語史」 (2021/11/27)

・ 「#181. 古ノルド語からの借用語がなかったら英語は話せない!?」 (2021/11/28)

・ 「#182. egg 「卵」は古ノルド語からの借用語!」 (2021/11/29)

・ 「#105. want の原義は「欠けている」」 (2021/09/14)

・ 「#317. dream, bloom, dwell ー 意味を借りた「意味借用」」 (2022/04/13)

・ 「#155. ノルド人とノルマン人は違います」 (2021/11/02)

2022-06-05 Sun

■ #4787. 英語とフランス語の間には似ている単語がたくさんあります [french][latin][loan_word][borrowing][notice][voicy][link][hel_education][lexicology][statistics][hellog_entry_set][sobokunagimon]

一昨日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」 にて「#368. 英語とフランス語で似ている単語がある場合の5つのパターン」という題でお話ししました.この放送に寄せられた質問に答える形で,本日「#370. 英語語彙のなかのフランス借用語の割合は? --- リスナーさんからの質問」を公開しましたので,ぜひお聴きください.

英語とフランス語の両方を学んでいる方も多いと思います.Voicy でも何度か述べていますが,私としては両言語を一緒に学ぶことをお勧めします.さらに,両言語の知識をつなぐものとして「英語史」がおおいに有用であるということも,お伝えしたいと思います.英語史を学べば学ぶほど,フランス語にも関心が湧きますし,その点を押さえつつフランス語を学ぶと,英語もよりよく理解できるようになります.そして,それによってフランス語がわかってくると,両言語間の関係を常に意識するようになり,もはや別々に考えることが不可能な境地(?)に至ります.英語学習もフランス語学習も,ともに楽しくなること請け合いです.

実際,語彙に関する限り,英語語彙の1/3ほどがフランス語「系」の単語によって占められます.フランス語「系」というのは,フランス語と,その生みの親であるラテン語を合わせた,緩い括りです.ここにフランス語の姉妹言語であるポルトガル語,スペイン語,イタリア語などからの借用語も加えるならば,全体のなかでのフランス語「系」の割合はもう少し高まります.

さて,その1/3のなかでの両言語の内訳ですが,ラテン語がフランス語を上回っており 2:1 あるいは 3:2 ほどいでしょうか.ただし,両言語は同系統なので語形がほとんど同一という単語も多く,英語がいずれの言語から借用したのかが判然としないケースもしばしば見られます.そこで実際上は,フランス語「系」(あるいはラテン語「系」)の語彙として緩く括っておくのが便利だというわけです.

このような英仏語の語彙の話題に関心のある方は,ぜひ関連する heldio の過去放送,および hellog 記事を通じて関心を深めていただければと思います.以下に主要な放送・記事へのリンクを張っておきます.実りある両言語および英語史の学びを!

[ heldio の過去放送 ]

・ 「#26. 英語語彙の1/3はフランス語!」

・ 「#329. フランス語を学び始めるならば,ぜひ英語史概説も合わせて!」

・ 「#327. 新年度にフランス語を学び始めている皆さんへ,英語史を合わせて学ぶと絶対に学びがおもしろくなると約束します!」

・ 「#368. 英語とフランス語で似ている単語がある場合の5つのパターン」

[ hellog の過去記事(一括アクセスはこちらから) ]

・ 「#202. 現代英語の基本語彙600語の起源と割合」 ([2009-11-15-1])

・ 「#429. 現代英語の最頻語彙10000語の起源と割合」 ([2010-06-30-1])

・ 「#845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合」 ([2011-08-20-1])

・ 「#1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)」 ([2012-08-11-1])

・ 「#874. 現代英語の新語におけるソース言語の分布」 ([2011-09-18-1])

・ 「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1])

・ 「#2357. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計」 ([2015-10-10-1])

・ 「#2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2)」 ([2015-11-07-1])

・ 「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1])

・ 「#4138. フランス借用語のうち中英語期に借りられたものは4割強で,かつ重要語」 ([2020-08-25-1])

・ 「#660. 中英語のフランス借用語の形容詞比率」 ([2011-02-16-1])

・ 「#1209. 1250年を境とするフランス借用語の区分」 ([2012-08-18-1])

・ 「#594. 近代英語以降のフランス借用語の特徴」 ([2010-12-12-1])

・ 「#1225. フランス借用語の分布の特異性」 ([2012-09-03-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

・ 「#1205. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか」 ([2012-08-14-1])

・ 「#2349. 英語の復権期にフランス借用語が爆発したのはなぜか (2)」 ([2015-10-02-1])

・ 「#4451. フランス借用語のピークは本当に14世紀か?」 ([2021-07-04-1])

・ 「#1638. フランス語とラテン語からの大量語彙借用のタイミングの共通点」 ([2013-10-21-1])

・ 「#1295. フランス語とラテン語の2重語」 ([2012-11-12-1])

・ 「#653. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別」 ([2011-02-09-1])

・ 「#848. 中英語におけるフランス借用語とラテン借用語の区別 (2)」 ([2011-08-23-1])

・ 「#3581. 中英語期のフランス借用語,ラテン借用語,"mots savants" (1)」 ([2019-02-15-1])

・ 「#3582. 中英語期のフランス借用語,ラテン借用語,"mots savants" (2)」 ([2019-02-16-1])

・ 「#4453. フランス語から借用した単語なのかフランス語の単語なのか?」 ([2021-07-06-1])

・ 「#3180. 徐々に高頻度語の仲間入りを果たしてきたフランス・ラテン借用語」 ([2018-01-10-1])

2022-05-16 Mon

■ #4767. 英語史で斬る,日本語のカタカナ語を巡る問題 [youtube][waseieigo][japanese][katakana][borrowing][lexicology][loan_word]

昨日18:00に YouTube 番組「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の第23弾が公開されました.タイトルは「カタカナ語を利用して日本人の英語力+情報収集力を上げる!!【井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル # 23 】」です.

ちなみに,先週の水曜日に公開された1つ前の第22弾は「ニッポンのカタカナ語を英語史から斬る!【井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル # 22 】」でした.2回かけて「カタカナ語」についておしゃべりしてきたわけです.ぜひ2つ合わせてご覧ください.

本ブログでもカタカナ語について様々に取り上げてきました.こちらの記事セットをご覧いただければと思います.

第22弾で話題にした「和製英語」ならぬ「英製羅語」や「英製仏語」についても,本ブログで議論してきました.こちらについては「和製英語を含む○製△語」の記事セットをどうぞ.

井上逸兵氏も様々な媒体で「カタカナ語」の議論を展開しています.最近のものとしては以下がおもしろいです.

・ 2021年11月20日,ABEMA Prime での:【横文字】「カタカナ語の輸入は止められない」「日本語で表せない表現も」意識高い系うざい?共有言語でアグリー?賛成派と反対派が議論

・ 2022年4月21日,SBSラジオ「IPPO」での:コンプライアンス?アジェンダ?今さら聞けない!カタカナ語

2022-04-16 Sat

■ #4737. 近い2言語(方言)どうしの接触についての Millar の見解 [contact][borrowing][simplification]

Millar は2016年の著書のなかで,言語接触 (contact) を論じる際には,接触する2言語の言語的近さを考慮する必要があると論じている.遠い2言語どうしの接触と,近い2言語,あるいは同一言語の2つの方言どうしの接触とでは,様相が異なるはずだと考えている.

Millar のこの見方は常識的であり,力説する必要もない,と思われるかもしれない.しかし,接触言語学の分野で絶大な影響力を誇る Thomason and Kaufman と Thomason においては,言語的な近さは言語接触を論じる上でさほど重要なパラメータとしてとらえられていない.関与し得るとしても,最も弱い関与にとどまるという消極的な役割しか与えられていないのである(cf. 「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]),「#1780. 言語接触と借用の尺度」 ([2014-03-12-1]),「#1781. 言語接触の類型論」 ([2014-03-13-1])).

Millar の主張は,このような学史的な背景のもとになされたものである.Millar (9--10) は,Thomason による言語接触に関する4段階の尺度を紹介した後に,主に2点について批判している.

1つは,くだんの尺度は,言語接触の1側面である借用 (borrowing) に大きく偏った尺度となっており,干渉 (interference) を十分に考慮したものとはなっていないということだ (cf. 「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1])).言語接触による単純化 (simplification) などの重要な話題が取りこぼされてしまっているという.

2つめは,上述の通り,Thomason (and Kaufman) は概して接触する2言語間の言語的近さというパラメータを軽視しているが,Millar が著書を通じて論じているように,実際には重要なパラメータだということである.Millar (10) は序章において次のように述べている.

. . . close linguistic relationship makes for a much more nuanced (and sometimes unexpected) series of contact-induced outcomes. We also have to include into such an analysis a discussion of occasions of near-relative contact where the two (or more) varieties involved would normally be considered dialects of the same language.

接触言語学の領域も着実に議論と知見が深化してきているように思う.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. Contact: The Interaction of Closely Related Linguistic Varieties and the History of English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2016.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey. Language Contact. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2001.

2022-02-12 Sat

■ #4674. 「初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み」 [slide][contrastive_linguistics][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][latin][japanese_history][contrastive_language_history]

3週間前のことですが,1月22日(土)に,ひと・ことばフォーラムのシンポジウム「言語史と言語的コンプレックス ー 「対照言語史」の視点から」の一環として「初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み」をお話しする機会をいただきました.Zoom によるオンライン発表でしたが,その後のディスカッションを含め,たいへん勉強になる時間でした.主催者の方々をはじめ,シンポジウムの他の登壇者や出席者参加者の皆様に感謝申し上げます.ありがとうございました.

私の発表は,すでに様々な機会に公表してきたことの組み替えにすぎませんでしたが,今回はシンポジウムの題に含まれる「対照言語史」 (contrastive_linguistics) を意識して,とりわけ日本語史における語彙拡充の歴史との比較対照を意識しながら情報を整理しました.

当日利用したスライドを公開します.スライドからは本ブログ記事へのリンクも多く張られていますので,合わせてご参照ください.

1. ひと・ことばフォーラム言語史と言語的コンプレックス ー 「対照言語史」の視点から初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み

2. 初期近代英語期における語彙拡充の試み

3. 目次

4. 1. はじめに --- 16世紀イングランド社会の変化

5. 2. 統合失調症の英語 --- ラテン語への依存とラテン語からの独立

6. 英語が抱えていた3つの悩み

7. 3. 独立を目指して

8. 4. 依存症の深まり (1) --- 語源的綴字

9. 5. 依存症の深まり (2) --- 語彙拡充

10. オープン借用,むっつり借用,○製△語

11. 6.「インク壺語」の大量借用

12. 7. 大量借用への反応

13. 8. インク壺語,チンプン漢語,カタカナ語の対照言語史

14. 9. まとめ

15. 語彙拡充を巡る独・日・英の対照言語史

16. 参考文献

2021-11-25 Thu

■ #4595. 強調構文に関する「ケルト語仮説」 [celtic][borrowing][syntax][contact][substratum_theory][celtic_hypothesis][cleft_sentence][irish_english]

「#2442. 強調構文の発達 --- 統語的現象から語用的機能へ」 ([2016-01-03-1]),「#3754. ケルト語からの構造的借用,いわゆる「ケルト語仮説」について」 ([2019-08-07-1]) で取り上げてきたように,「強調構文」として知られている構文の起源と発達については様々な見解がある(ちなみに英語学では「分裂文」 (cleft_sentence) と呼ぶことが多い).

比較的最近の新しい説によると,英語における強調構文の成長は,少なくとも部分的にはケルト語との言語接触に帰せられるのではないかという「ケルト語仮説」 (celtic_hypothesis) が提唱されている.伝統的には,ケルト語との接触による英語の言語変化は一般に微々たるものであり,あったとしても語彙借用程度にとどまるという見方が受け入れられてきた.しかし,近年勃興してきたケルト語仮説によれば,英語の統語論や音韻論などへの影響の可能性も指摘されるようになってきている.英語の強調構文の発達も,そのような事例の1候補として挙げられている.

先行研究によれば,古英語での強調構文の事例は少ないながらも見つかっている.例えば以下のような文である (Filppula and Klemola 1695 より引用).

þa cwædon þa geleafullan, 'Nis hit na Petrus þæt þær cnucað, ac is his ængel.' (Then the faithful said: It isn't Peter who is knocking there, but his angel.)

Filppula and Klemola (1695--96) の調査によれば,この構文の頻度は中英語期にかけて上がってきたという.そして,この発達の背景には,ケルト語における対応表現の存在があったのではないかとの仮説を提起している.論拠の1つは,アイルランド語を含むケルト諸語に,英語よりも古い時期から対応表現が存在していたという点だ.実はフランス語にも同様の強調構文が存在し,むしろフランス語からの影響と考えるほうが妥当ではないかという議論もあるが,ケルト諸語での使用のほうが古いということがケルト語仮説にとっての追い風となっている.

もう1つの論拠は,現代アイルランド英語 (irish_english) で,英語の強調構文よりも統語的自由度の高い強調構文が広く使われているという事実だ.例えば,次のような自由さで用いられる (Filppula and Klemola 1698 より引用).

・ It is looking for more land they are.

・ Tis joking you are, I suppose.

・ Tis well you looked.

このようなアイルランド英語における,統語的制限の少ない強調構文の使用は,そのような特徴をもつケルト語の基層の上に英語が乗っかっているためと解釈することができる.いわゆる「基層言語仮説」 (substratum_theory) に訴える説明だ.

今回の強調構文の事例だけではなく,一般にケルト語仮説に対しては異論も多い.しかし,古英語期(以前)から現代英語期に及ぶ長大な時間を舞台とする英語とケルト語の言語接触論は,確かにエキサイティングではある.

・ Filppula, Markku and Juhani Klemola. "English in Contact: Celtic and Celtic Englishes." Chapter 107 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1687--1703.

2021-10-13 Wed

■ #4552. borrowing, transfer, convergence [terminology][contact][borrowing][language_shift]

言語接触 (contact) に関わる標題の3つの重要な用語を解説する.このような用語を用いる際に注意すべき点は,論者によって何を指すかが異なり得ることだ.ここでは当該分野の専門家である Hickey (486--87) の定義を引用したい.

(1) Borrowing. Items/structures are copied from language X to language Y, but without speakers of Y shifting to X. In this simple form, borrowing is characteristic of "cultural" contact (e.g. Latin and English in the history of the latter, or English and other European languages today). Such borrowings are almost exclusively confined to words and phrases.

(2) Transfer. During language shift, when speakers of language X are switching to language Y, they transfer features of their original native language X to Y. Where these features are not present in Y they represent an innovation. For grammatical structures one can distinguish (i) categories and (ii) their realizations, either or both of which can be transferred.

(3) Convergence. A feature in language X has an internal source (i.e. there is a systemic motivation for the feature within language X), and the feature is present in a further language Y with which X is in contact. Both internal and external sources "converge" to produce the same result as with the progressive form in English. . . .

この3つの区分は,接触に起因する過程の agentivity が X, Y のいずれの言語話者側にあるのか,あるいは両側にあるのかに対応するといってよい.この agentivity の観点については「#3968. 言語接触の2タイプ,imitation と adaptation」 ([2020-03-08-1]),「#3969. ラテン語,古ノルド語,ケルト語,フランス語が英語に及ぼした影響を比較する」 ([2020-03-09-1]) も参照.

・ Hickey, Raymond. "Assessing the Role of Contact in the History of English." Chapter 37 of The Oxford Handbook of the History of English. Ed. Terttu Nevalainen and Elizabeth Closs Traugott. New York: OUP, 2012. 485--96.

2021-09-25 Sat

■ #4534. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? (3) [old_norse][contact][koine][koineisation][borrowing][language_shift][simplification][inflection][substratum_theory]

8世紀後半から11世紀にかけてイングランド北部の英語は古ノルド語と濃厚に接触した.この言語接触 (contact) は後の英語の形成に深遠な影響を及ぼし,英語史上の意義も大きいために,非常に多くの研究がなされ,蓄積されてきた.本ブログでも,古ノルド語に関する話題は old_norse の多くの記事で取り上げてきた.

この言語接触の著しい特徴は,単なる語彙借用にとどまらず,形態論レベルにも影響が及んでいる点にある.主に屈折語尾の単純化 (simplification) や水平化 (levelling) に関して,言語接触からの貢献があったことが指摘されている.しかし,この言語接触が,言語接触のタイポロジーのなかでどのような位置づけにあるのか,様々な議論がある.

この分野に影響力のある Thomason and Kaufman (97, 281) の見立てでは,当該の言語接触の水準は,借用 (borrowing) か,あるいは言語交替 (language_shift) による影響といった水準にあるだろうという.これは,両方の言語の話者ではなく一方の言語の話者が主役であるという見方だ.

一方,両言語の話者ともに主役を演じているタイプの言語接触であるという見解がある.類似する2言語(あるいは2方言)の話者が互いの妥協点を見つけ,形態を水平化させていくコイネー化 (koineisation) の過程ではないかという説だ.この立場については,すでに「#3972. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か?」 ([2020-03-12-1]) と「#3980. 古英語と古ノルド語の接触の結果は koineisation か? (2)」 ([2020-03-20-1]) でも紹介してきたが,今回は Winford (82--83) が Dawson に依拠しつつ解説している部分を引用したい.

Hope Dawson (2001) suggests that the variety of Northern English that emerged from the contact between Viking Norse and Northern Old English was in fact a koiné --- a blend of elements from the two languages. The formation of this compromise variety involved selections from both varieties, with gradual elimination of competition between variants through leveling (selection of one option). This suggestion is attractive, since it explains the retention of Norse grammatical features more satisfactorily than a borrowing scenario does. We saw . . . that the direct borrowing of structural features (under RL [= recipient language] agentivity) is rather rare. The massive diffusion of Norse grammatical features into Northern Old English is therefore not what we would expect if the agents of change were speakers of Old English importing Norse features into their speech. A more feasible explanation is that both Norse and English speakers continued to use their own varieties to each other, and that later generations of bilingual or bidialectal speakers (especially children) forged a compromise language, as tends to happen in so many situations of contact.

接触言語学の界隈では,コイネー化の立場を取る論者が増えてきているように思われる.

・ Thomason, Sarah Grey and Terrence Kaufman. Language Contact, Creolization, and Genetic Linguistics. Berkeley: U of California P, 1988.

・ Dawson, Hope. "The Linguistic Effects of the Norse Invasion of England." Unpublished ms, Dept of Linguistics, Ohio State U, 2001.

・ Winford, Donald. An Introduction to Contact Linguistics. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2003.

2021-09-05 Sun

■ #4514. code-switching と convergence [terminology][code-switching][bilingualism][multilingualism][borrowing][world_englishes]

連日 World Englishes のハンドブックを読み進めている.今回取り上げるのは "World Englishes, Code-Switching, and Convergence" と題する章だ.世界英語は2言語使用 (bilingualism) あるいは多言語使用 (multilingualism) の環境で用いられることが多いが,共通の言語的レパートリーをもつ2(多)言語使用者どうしが共通の英語変種を用いて会話する機会が多い社会において,複数言語の使用の観点からは対照的な2つのことが起こり得る.

1つは,共通する2つの言語をところどころで切り替えながら会話を進める code-switching である.たとえて言えば白黒白黒白黒白黒・・・と続けることによって,平均量として灰色に至る状況だ.ここでは2つの言語の自立性は保たれる.

一方,共通する2つの言語の要素を混ぜる,あるいは互いに近似させることによって灰灰灰灰灰灰灰灰・・・とし,質として灰色に至るということもあるだろう.これが convergence と呼ばれるものである.ここでは各言語の自立性は小さくなる.

このように code-switching と convergence は,ともに同じような社会言語学的条件下で生じ得るものの,反対の方向を向いている.両者がこのような関係にあったとは,これまで気づかなかった.Bullock et al. (218) より,この対比について説明している箇所を引用しよう.

Bilingual speech comprises diverse types of language mixing phenomena, of which CS [= code-switching] is but one example. Another process that may arise in bilingual speech is convergence. CS is characterized by divergence; it is the alternation between linguistic systems that are kept distinct. In convergence, on the other hand, the perceived distance between the language systems is narrowed such that they become structurally more similar, sometimes to the extreme point that the boundaries between languages collapse. In such cases, it is quite possible that the structural constraints that once functioned to preserve the autonomy of the languages while a speaker code-stitches between them are gradually abandoned. As bilingual speakers perceive more overlap between languages, they may mix more liberally between them.

code-switching と convergence の対比はあくまで図式的・理論的なものであり,実際上は両者の区別は曖昧であり,連続体の両端を構成するものと理解しておくのが妥当だろう.この点では,「#1661. 借用と code-switching の狭間」 ([2013-11-13-1]),「#1985. 借用と接触による干渉の狭間」 ([2014-10-03-1]),「#2009. 言語学における接触,干渉,2言語使用,借用」 ([2014-10-27-1]) などでみた,code-switching なのか借用なのか区別が不明瞭という問題にも関わってくる.

・ Bullock, Barbara E., Lars Hinrichs, and Almeida Jacqueline Toribio. "World Englishes, Code-Switching, and Convergence." Chapter 11 of The Oxford Handbook of World Englishes. Ed. by Markku Filppula, Juhani Klemola, and Devyani Sharma. New York: OUP, 2017. 211--31.

2021-08-22 Sun

■ #4500. 文字体系を別の言語から借りるときに起こり得ること6点 [grapheme][graphology][alphabet][writing][diacritical_mark][ligature][digraph][runic][borrowing][y]

自らが文字体系を生み出した言語でない限り,いずれの言語もすでに他言語で使われていた文字を借用することによって文字の運用を始めたはずである.しかし,自言語と借用元の言語は当然ながら多かれ少なかれ異なる言語特徴(とりわけ音韻論)をもっているわけであり,文字の運用にあたっても借用元言語での運用が100%そのまま持ち越されるわけではない.言語間で文字体系が借用されるときには,何らかの変化が生じることは避けられない.これは,6世紀にローマ字が英語に借用されたときも然り,同世紀に漢字が日本語に借用されたときも然りである.

Görlach (35) は,文字体系の借用に際して何が起こりうるか,6点を箇条書きで挙げている.主に表音文字であるアルファベットの借用を念頭に置いての箇条書きと思われるが,以下に引用したい.

Since no two languages have the same phonemic inventory, any transfer of an alphabet creates problems. The following solutions, especially to render 'new' phonemes, appear to be the most common:

1. New uses for unnecessary letters (Greek vowels).

2. Combinations (E. <th>) and fusions (Gk <ω>, OE <æ>, Fr <œ>, Ge <ß>).

3. Mixture of different alphabets (Runic additions in OE; <ȝ>: <g> in ME).

4. Freely invented new symbols (Gk <φ, ψ, χ, ξ>).

5. Modification of existing letters (Lat <G>, OE <ð>, Polish <ł>).

6. Use of diacritics (dieresis in Ge Bär, Fr Noël; tilde in Sp mañana; cedilla in Fr ça; various accents and so on).

なるほど,既存の文字の用法が変わるということもあれば,新しい文字が作り出されるということもあるというように様々なパターンがありそうだ.ただし,これらの多くは確かに言語間での文字体系の借用に際して起こることは多いかもしれないが,そうでなくても自発的に起こり得る項目もあるのではないか.

例えば上記1については,同一言語内であっても通時的に起こることがある.古英語の <y> ≡ /y/ について,中英語にかけて同音素が非円唇化するに伴って,同文字素はある意味で「不要」となったわけだが,中英語期には子音 /j/ を表わすようになったし,語中位置によって /i/ の異綴りという役割も獲得した.ここでは,言語接触は直接的に関わっていないように思われる (cf. 「#3069. 連載第9回「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」」 ([2017-09-21-1])) .

・ Görlach, Manfred. The Linguistic History of English. Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1997.

2021-08-03 Tue

■ #4481. 英語史上,2度借用された語の位置づけ [lexicography][lexicology][borrowing][loan_word][latin][lexeme]

英語史上,2度借用された語というものがある.ある時代にあるラテン語単語などが借用された後,別の時代にその同じ語があらためて借用されるというものである.1度目と2度目では意味(および少し形態も)が異なっていることが多い.

例えば,ラテン語 magister は,古英語の早い段階で借用され,若干英語化した綴字 mægester で用いられていたが,10世紀にあらためて magister として原語綴字のまま受け入れられた (cf. 「#1895. 古英語のラテン借用語の綴字と借用の類型論」 ([2014-07-05-1])).

中英語期と初期近代英語期からも似たような事例がみられる.fastidious というラテン語単語は1440年に「傲岸不遜な」の語義で借用されたが,その1世紀後には「いやな,不快な」の語義で用いられている(後者は現代の「気難しい,潔癖な」の語義に連なる).また,Chaucer は artificial, declination, hemisphere を天文学用語として導入したが,これらの語の現在の非専門的な語義は,16世紀の再借用時の語義に基づく.この中英語期からの例については,Baugh and Cable (222--23) が次のような説明を加えている.

A word when introduced a second time often carries a different meaning, and in estimating the importance of the Latin and other loanwords of the Renaissance, it is just as essential to consider new meanings as new words. Indeed, the fact that a word had been borrowed once before and used in a different sense is of less significance than its reintroduction in a sense that has continued or been productive of new ones. Thus the word fastidious is found once in 1440 with the significance 'proud, scornful,' but this is of less importance than the fact that both More and Elyot use it a century later in its more usual Latin sense of 'distasteful, disgusting.' From this, it was possible for the modern meaning to develop, aided no doubt by the frequent use of the word in Latin with the force of 'easily disgusted, hard to please, over nice.' Chaucer uses the words artificial, declination, and hemisphere in astronomical sense but their present use is due to the sixteenth century; and the word abject, although found earlier in the sense of 'cast off, rejected,' was reintroduced in its present meaning in the Renaissance.

もちろん見方によっては,上記のケースでは,同一単語が2度借用されたというよりは,既存の借用語に対して英語側で意味の変更を加えたというほうが適切ではないかという意見はあるだろう.新旧間の連続性を前提とすれば「既存語への変更」となり,非連続性を前提とすれば「2度の借用」となる.しかし,Baugh and Cable も引用中で指摘しているように,語源的には同一のラテン語単語にさかのぼるとしても,英語史の観点からは,実質的には異なる時代に異なる借用語を受け入れたとみるほうが適切である.

OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた辞書の編纂を念頭におくと,fastidious なり artificial なりに対して,1つの見出し語を立て,その下に語義1(旧語義)と語義2(新語義)などを配置するのが常識的だろうが,各時代の話者の共時的な感覚に忠実であろうとするならば,むしろ fastidious1 と fastidious2 のように見出し語を別に立ててもよいくらいのものではないだろうか.後者の見方を取るならば,後の歴史のなかで旧語義が廃れていった場合,これは廃義 (dead sense) というよりは廃語 (dead word) というべきケースとなる.いな,より正確には廃語彙項目 (dead lexical item; dead lexeme) と呼ぶべきだろうか.

この問題と関連して「#3830. 古英語のラテン借用語は現代まで地続きか否か」 ([2019-10-22-1]) も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2021-07-30 Fri

■ #4477. フランス語史における語彙借用の概観 [french][borrowing][loan_word][hfl]

本ブログでは,英語史における語彙借用について数多くの記事で紹介してきた.英語史研究では,英語がどの言語からどのような/どれだけの語を何世紀頃に借りてきたのかという問題は,主に OED などを用いた調査を通じて詳しく取り扱われてきており,多くのことが明らかにされている.(具体的には borrowing statistics などの各記事を参照されたい.)

では,英語史とも関連の深いフランス語について,同様の問いを発してみるとどうなるだろうか.フランス語はどの言語からどのような/どれだけの語を何世紀頃に借りてきたのか.私は英語史を専門とする者なので直接調べてみたことはなかったが,たまたま Jones and Singh (31) に簡便な数値表を見つけたので,それを再現したい(もともとは Guiraud (6) の調査結果を基にした表とのこと).

| Century | 12th | 13th | 14th | 15th | 16th | 17th | 18th | 19th |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arabic | 20 | 22 | 36 | 26 | 70 | 30 | 24 | 41 |

| Italian | 2 | 7 | 50 | 79 | 320 | 188 | 101 | 67 |

| Spanish | 5 | 11 | 85 | 103 | 43 | 32 | ||

| Portuguese | 1 | 19 | 23 | 8 | 3 | |||

| Dutch | 16 | 23 | 35 | 22 | 32 | 52 | 24 | 10 |

| Germanic | 5 | 12 | 5 | 11 | 23 | 27 | 33 | 45 |

| English | 8 | 2 | 11 | 6 | 14 | 67 | 134 | 377 |

| Slavic | 2 | 1 | 4 | 6 | 11 | 10 | ||

| Turkish | 1 | 2 | 13 | 9 | 6 | 14 | ||

| Persian | 2 | 2 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 1 | ||

| Hindu | 1 | 4 | 8 | 5 | ||||

| Malaysian | 4 | 10 | 6 | 5 | ||||

| Japanese/Chinese | 36 | 25 | 21 | 7 | ||||

| Greek | 8 | 4 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 2 | ||

| Hebrew | 9 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

表を眺めるだけで,いろいろなことが分かってくる.フランス語では16--17世紀にイタリア語からの借用語が多かったようだが,これは英語でも同様である.当時イタリア語はヨーロッパにおいて洗練された文化的な言語として威信を誇っていたからである.18世紀以降,イタリア語の威信は衰退したが,今度はそれと入れ替わるかのように英語が語彙供給言語として台頭してきた.なお,スペイン語も,こじんまりとしているが,イタリア語と似たような分布を示す.この点でも,フランス語史と英語史はパラレルである.

アラビア語やオランダ語からは歴史を通じて一定のペースで単語が流入してきたというのもおもしろい.特にアラビア語については,英語史ではさほど目立たないため,私には意外だった.日本語と中国語はひっくるめて数えられているものの,16世紀以降にある程度の語彙をフランス語に供給していることが分かる.これについては英語史でもおよそパラレルな状況が見られる.

語彙借用の傾向についてフランス語史と英語史を比べてみると,当然ながら類似点と相違点があるだろうが,おもしろい比較となりそうだ.

・ Jones, Mari C. and Ishtla Singh. Exploring Language Change. Abingdon: Routledge, 2005.

・ Guiraud, P. Les Mots Etrangers. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France, 1965.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow