2017-12-15 Fri

■ #3154. 英語史上,色彩語が増加してきた理由 [bct][borrowing][lexicology][french][loan_word][sociolinguistics]

「#2103. Basic Color Terms」 ([2015-01-29-1]) および昨日の記事「#3153. 英語史における基本色彩語の発展」 ([2017-12-14-1]) で,基本色彩語 (Basic Colour Terms) の普遍的発展経路の話題に触れた.英語史においても,BCTs の種類は,普遍的発展経路から予想される通りの順序で,古英語から中英語へ,そして中英語から近代英語へと着実に増加してきた.そして,BCTs のみならず non-BCTs も時代とともにその種類を増してきた.これらの色彩語の増加は何がきっかけだったのだろうか.

Biggam (123--24) によれば,古英語から中英語にかけての増加は,ノルマン征服後のフランス借用語に帰せられるという.BCTs に関していえば,中英語で加えられたbleu は確かにフランス語由来だし,brun は古英語期から使われていたものの Anglo-French の brun により使用が強化されたという事情もあったろう.また,色合,濃淡 ,彩度,明度を混合させた古英語の BCCs 基準と異なり,中英語期にとりわけ色合を重視する BCCs 基準が現われてきたのは,ある産業技術上の進歩に起因するのではないかという指摘もある.

The dominance of hue in certain ME terms, especially in BCTs, was at least encouraged by certain cultural innovations of the later Middle Ages such as banners, livery, and the display of heraldry on coats-of-arms, all of which encouraged the development and use of strong dyes and paints. (125)

近代英語期になると,PURPLE, ORANGE, PINK が BCCs に加わり,近現代的な11種類が出そろうことになったが,この時期にはそれ以外にもおびただしい non-BCTs が出現することになった.これも,近代期の社会や文化の変化と連動しているという.

From EModE onwards, the colour vocabulary of English increased enormously, as a glance at the HTOED colour categories reveals. Travellers to the New World discovered dyes such as logwood and some types of cochineal, while Renaissance artists experimented with pigments to introduce new effects to their paintings. Much later, synthetic dyes were introduced, beginning with so-called 'mauveine', a purple shade, in 1856. In the same century, the development of industrial processes capable of producing identical items which could only be distinguished by their colours encouraged the proliferation of colour terms to identify and market such products. The twentieth century saw the rise of the mass fashion industry with its regular announcements of 'this year's colours'. In periods like the 1960s, colour, especially vivid hues, seemed to dominate the cultural scene. All of these factors motivated the coining of new colour terms. The burgeoning of the interior décor industry, which has a never-ending supply of subtle mixes of hues and tones, also brought colour to the forefront of modern minds, resulting in a torrent of new colour words and phrases. It has been estimated that Modern British English has at least 8,000 colour terms . . . . (126)

英語の色彩語の歴史を通じて,ちょっとした英語外面史が描けそうである.

・ Kay, Christian and Kathryn Allan. English Historical Semantics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015.

・ Biggam, C. P. "English Colour Terms: A Case Study." Chapter 7 of English Historical Semantics. Christian Kay and Kathryn Allan. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2015. 113--31.

2017-12-07 Thu

■ #3146. 言語における「遺伝的関係」とは何か? (1) [terminology][comparative_linguistics][family_tree][methodology][typology][borrowing][linguistics][sobokunagimon]

歴史言語学において,共通祖語をもつ言語間の発生・発達関係は "genetic relationship" と呼ばれる.本来生物学に属する "genetics" という用語を言語に転用することは広く行なわれ,当然のものとして受け入れられてきた.しかし,真剣に考え出すと,それが何を意味するかは,まったく自明ではない.この用語遣いの背景には様々な前提が隠されており,しかもその前提は論者によって著しく異なっている.この問題について,Noonan (48--49) が比較的詳しく論じているので,参照してみた.今回の記事では,言語における遺伝的関係とは何かというよりも,何ではないかということを明らかにしたい.

まず力説すべきは,言語の遺伝的関係とは,その話者集団の生物学的な遺伝的関係とは無縁ということである.現代の主流派言語学では,人種などの遺伝学的,生物学的な分類と言語の分類とは無関係であることが前提とされている.個人は,どの人種のもとに生まれたとしても,いかなる言語をも習得することができる.個人の習得する言語は,その遺伝的特徴により決定されるわけではなく,あくまで生育した社会の言語環境により決定される.したがって,言語の遺伝的関係の議論に,話者の生物学的な遺伝の話題が入り込む余地はない.

また,言語類型論 (linguistic typology) は,言語間における言語項の類似点・相違点を探り,何らかの関係を見出そうとする分野ではあるが,それはあくまで共時的な関係の追求であり,遺伝的関係について何かを述べようとしているわけではない.ある2言語のあいだの遺伝的関係が深ければ,言語が構造的に類似しているという可能性は確かにあるが,そうでないケースも多々ある.逆に,構造的に類似している2つの言語が,異なる系統に属するということはいくらでもあり得る.そもそも言語項の借用 (borrowing) は,いかなる言語間にあっても可能であり,借用を通じて共時的見栄えが類似しているにすぎないという例は,古今東西,数多く見つけることができる.

では,言語における遺伝的関係とは,話者集団の生物学的な遺伝的関係のことではなく,言語類型論が指摘するような共時的類似性に基づく関係のことでもないとすれば,いったい何のことを指すのだろうか.この問いは,歴史言語学においてもほとんど明示的に問われたことがないのではないか.それにもかかわらず日常的にこの用語が使われ続けてきたのだとすれば,何かが暗黙のうちに前提とされてきたことになる.英語は遺伝的にはゲルマン語派に属するとか,日本語には遺伝的関係のある仲間言語がないなどと言うとき,そこにはいかなる言語学上の前提が含まれているのか.これについて,明日の記事で考えたい.

・ Noonan, Michael. "Genetic Classification and Language Contact." The Handbook of Language Contact. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010. 2013. 48--65.

2017-11-05 Sun

■ #3114. 文化的優劣,政治的優劣,語彙借用 [sociolinguistics][contact][borrowing]

昨日の記事「#3113. アングロサクソン人は本当にイングランドを素早く征服したのか?」 ([2017-11-04-1]) で,接触言語どうしの社会言語学的な関係を記述する場合に,文化軸と政治軸を分けて考えるやり方があり得ると言及した.早速,これを英語史上の主要な言語接触に当てはめてみると,およそ次のような図式が得られる.

政治的優劣 文化・政治的同列 文化・政治的優劣 文化的優劣 ┌─────┐ ┌───────┐ ┌───────┐ │ │ │ │ │ ラテン語 │ │ 英 語 │ ┌───────┬───────┐ │ フランス語 │ │ or │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ ギリシア語 │ ├─────┤ │ 英 語 │ 古ノルド語 │ ├───────┤ ├───────┤ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ │ ケルト │ └───────┴───────┘ │ 英 語 │ │ 英 語 │ │ │ │ │ │ │ └─────┘ └───────┘ └───────┘

まず,5世紀半ばの英語とケルト語の関係でいえば,英語はケルト語に対して政治的(軍事的)には優位に立っていたが,昨日の記事でも触れたように,文化的には必ずしも優位に立っていたわけではない.この言語接触については,あくまで「政治的優劣」の関係にとどまっていたとみなすことができる.

次に,後期古英語からの英語と古ノルド語の関係についていえば,両言語の話者集団は文化的にも政治的にもおよそ同列であり,いずれかが著しく勝っていたというわけではない.確かに言語接触の背景にはヴァイキングの軍事的な成功があったが,彼我の力関係は歴然としたものではなかった.

続いて,中英語期の英語とフランス語の接触についていえば,ノルマン征服による明確な政治的・軍事的な優劣を背景として,その後,文化的な優劣の関係も生じることになった.

最後に,初期近代英語期の英語とラテン語・ギリシア語の接触に関しては,政治的な含みはないといってよく,関与するのはもっぱら文化軸においてである.

このように見てくると,英語はその歴史のなかで,文化軸と政治軸の様々な組み合わせで,接触言語と関係してきたことがわかる.ある意味で,豊富な言語接触のパターンを試してきたともいえる.

このパターンと語彙借用との相関関係について何か指摘できることがあるとすれば,文化軸が関与している言語接触(古ノルド語,フランス語,ラテン語・ギリシア語)においては英語に関して語彙借用が生じているが,政治軸のみが関与している言語接触(ケルト語)では,上位の英語のみならず下位のケルト語においても,ほとんど語彙借用が生じていないのではないか,ということだ.優劣関係それ自体よりも,文化の政治のいずれの軸での優劣関係が問題となっているのかにより,語彙借用の多寡の傾向が決まるということかもしれない.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2017-10-12 Thu

■ #3090. 英語英文学は南方から滋養をとってきた [literature][borrowing][loan_word]

福原 (33) によれば,英文学がドイツ文学から影響を受け始めたのは,Carlyle の手を経ての19世紀のことであり,それ以前にはほとんどなかった.言語上の接触についても,「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]),「#2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から」 ([2016-06-30-1]) で触れたとおり,英語はドイツ語からの影響を比較的最近まで受けていなかった.英語の文学・言語がドイツの言語・文学と長らく接点をもたなかったことは,一般に英語英文学が,主に北方ではなく南方から滋養をとってきた歴史を反映している.福原 (33--34) は,英文学におけるこの歴史的傾向について次のように述べている.

英文學といふものは,どうも南方から滋養を取つてくるので,北方文學はあまり奮ひません.十九世紀末につてイプセンが來ます.それから,二十世紀になりまして,ロシア文學が入つて参りますけれども,どうも性に合はないらしく,トルストイもドストエフスキーも十分消化されないやうでありました.〔中略〕そんなわけで北よりも南,ことに十九世紀末は,フランスの頽廢派の文學に共鳴した友人達が輩出いたしました〔後略〕.

英語史,とりわけ英語の語彙借用史に照らしても,概ね「南方」の言語(フランス語,ラテン語,ギリシア語など)から滋養をとってきたことは事実である.確かに古ノルド語,低地地方の言語など「北方」のゲルマン諸語からの借用語もあったが,少なくとも量的な観点からみれば明らかに「南方」過多といってよいだろう.

文学にせよ言語にせよ,本来的に北方的な体質をもっていたところに,歴史的に南方的な滋養が入り込んで,現在あるような English ができあがってきた.これは,英文学史と英語史を大きく俯瞰する視点である.

・ 福原 麟太郎 『英文学入門』 河出書房,1951年.

2017-07-22 Sat

■ #3008. 「借用とは参考にした上での造語である」 [borrowing][neolinguistics][terminology]

先日大学の授業で,言語における借用 borrowing とは何かという問題について,特に借用語 (loan_word) を念頭に置きつつディスカッションしてみた.以前にも同じようなディスカッションをしたことがあり,本ブログでも「#44. 「借用」にみる言語の性質」 ([2009-06-11-1]),「#2010. 借用は言語項の複製か模倣か」 ([2014-10-28-1]) などで論じてきた.今回あらためて受講生の知恵を借りて考えたところ,新しい洞察が得られたので報告したい.

語の借用を考えるとき,そこで起こっていることは厳密にいえば「借りる」過程ではなく,したがって「借用」という表現はふさわしくない,ということはよく知られていた.そこで,以前の記事では「複製」 (copying),「模倣」 (imitation),「再創造」 (re-creation) 等の別の概念を持ち出して,現実と用語のギャップを埋めようとした.今回のディスカッションで学生から飛び出した洞察は,これらを上手く組み合わせた「参考にした上での造語」という見解である.単純に借りるわけでも,コピーするわけでも,模倣するわけでもない.相手言語におけるモデルを参考にした上で,自言語において新たに造語する,という見方だ.これは言語使用者の主体的で積極的な言語活動を重んじる,新言語学派 (neolinguistics) の路線に沿った言語観を表わしている.

主体性や積極性というのは,もちろん程度の問題である.それがゼロに近ければ事実上の「複製」や「模倣」とみなせるだろうし,最大限に発揮されれば「造語」や「創造」と表現すべきだろう.用語や概念は包括的なほうが便利なので「参考にした上での造語」という「借用」の定義は適切だと思うが,説明的で長いのが,若干玉に瑕である.

いずれにせよ非常に有益なディスカッションだった.

2017-07-01 Sat

■ #2987. ヨーロッパでそのまま通用する英語語句 [loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

英語は歴史を通じて様々な言語から数多くの単語を借用してきた.この事実について,最近では「#2966. 英語語彙の世界性 (2)」 ([2017-06-10-1]) で総括した.しかし,現代世界において,英語は語彙の借り入れ側というよりも,むしろ貸し出し側としての役割のほうが目立っている.近年,日本語にも無数の英単語がカタカナ語として流入しているし,世界の諸言語を見渡しても,英語から何らかの語彙的影響を被っていない言語はほぼ皆無だろう(カタカナ語問題については,「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) を参照).

独自の標準語が安定的に確立しているヨーロッパ諸国ですら,英語の語彙的影響は著しい.以下は,ヨーロッパの多くの言語でそのまま通用する英語語句の例である (Crystal 272) .

[ Sport ]

baseball, bobsleigh, clinch, comeback, deuce, football, goalie, jockey, offside, photo-finish, semi-final, volley, walkover

[ Tourism, transport etc. ]

antifreeze, camping, hijack, hitch-hike, jeep, joy-ride, motel, parking, picnic, runway, scooter, sightseeing, stewardess, stop (sign), tanker, taxi

[ Politics, commerce ]

big business, boom, briefing, dollar, good-will, marketing, new deal, senator, sterling, top secret

[ Culture, entertainment ]

cowboy, group, happy ending, heavy metal, hi-fi, jam session, jazz, juke-box, Miss World (etc.), musical, night-club, pimp, ping-pong, pop, rock, showbiz, soul, striptease, top twenty, Western, yeah-yeah-yeah

[ People and behaviour ]

AIDS, angry young man, baby-sitter, boy friend, boy scout, callgirl, cool, cover girl, crack (drugs), crazy, dancing, gangster, hash, hold-up, jogging, mob, OK, pin-up, reporter, sex-appeal, sexy, smart, snob, snow, teenager

[ Consumer society ]

air conditioner, all rights reserved, aspirin, bar, best-seller, bulldozer, camera, chewing gum, Coca Cola, cocktail, coke, drive-in, eye-liner, film, hamburger, hoover, jumper, ketchup, kingsize, Kleenex, layout, Levis, LP, make-up, sandwich, science fiction, Scrabble, self-service, smoking, snackbar, supermarket, tape, thriller, up-to-date, WC, weekend

これらの語句には,ヨーロッパのみならず日本語でもカタカナ語として通用しているものが多い.その意味では,世界的な語彙 (cosmopolitan vocabulary) に接近していると言えるかもしれない.

・ Crystal, David. The English Language. 2nd ed. London: Penguin, 2002.

2017-06-21 Wed

■ #2977. 連載第6回「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」 [notice][link][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology][french][latin][lexical_stratification][japanese][inkhorn_term][rensai][sobokunagimon]

昨日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第6回の記事「なぜ英語語彙に3層構造があるのか? --- ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれとインク壺語論争」が公開されました.

今回の話は,英語語彙を学ぶ際の障壁ともなっている多数の類義語セットが,いかに構造をなしており,なぜそのような構造が存在するのかという素朴な疑問に,歴史的な観点から迫ったものです.背景には,英語が特定の時代の特定の社会的文脈のなかで特定の言語と接触してきた経緯があります.また,英語語彙史をひもといていくと,興味深いことに,日本語語彙史との平行性も見えてきます.対照言語学的な日英語比較においては,両言語の違いが強調される傾向がありますが,対照歴史言語学の観点からみると,こと語彙史に関する限り,両言語はとてもよく似ています.連載記事の後半では,この点を議論しています.

英語語彙(と日本語語彙)の3層構造の話題については,拙著『英語の「なぜ?」に答える はじめての英語史』のの5.1節「なぜ Help me! とは叫ぶが Aid me! とは叫ばないのか?」と5.2節「なぜ Assist me! とはなおさら叫ばないのか?」でも扱っていますが,本ブログでも様々に議論してきたので,そのリンクを以下に張っておきます.合わせてご覧ください.また,同様の話題について「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1]) で紹介した拙論もこちらからご覧ください.

・ 「#334. 英語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-27-1])

・ 「#1296. 三層構造の例を追加」 ([2012-11-13-1])

・ 「#1960. 英語語彙のピラミッド構造」 ([2014-09-08-1])

・ 「#2072. 英語語彙の三層構造の是非」 ([2014-12-29-1])

・ 「#2279. 英語語彙の逆転二層構造」 ([2015-07-24-1])

・ 「#2643. 英語語彙の三層構造の神話?」 ([2016-07-22-1])

・ 「#387. trisociation と triset」 ([2010-05-19-1])

・ 「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1])

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1])

・ 「#120. 意外と多かった中英語期のラテン借用語」 ([2009-08-25-1])

・ 「#1211. 中英語のラテン借用語の一覧」 ([2012-08-20-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

・ 「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1])

・ 「#2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2)」 ([2015-11-07-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#335. 日本語語彙の三層構造」 ([2010-03-28-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1])

・ 「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

2017-06-10 Sat

■ #2966. 英語語彙の世界性 (2) [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][link]

英語語彙の世界性について,1年ほど前の記事 ([2016-06-24-1]) で様々なリンクを張ったが,その後書き足した記事もあるので,リンク等をアップデートしておきたい.記事を読み進めていけば,英語語彙史の概要が分かる.

1 数でみる英語語彙

1.1 語彙の規模の大きさ (#898)

1.2 語彙の種類の豊富さ (##756,309,202,429,845,1202,110,201,384)

1.3 英語語彙史の概略 (##37,1526,126,45)

2 語彙借用とは?

2.1 なぜ語彙を借用するのか? (##46,1794)

2.2 借用の5W1H:いつ,どこで,何を,誰から,どのように,なぜ借りたのか? (#37)

3 英語の語彙借用の歴史 (#1526)

3.1 大陸時代 (--449)

3.1.1 ラテン語 (#1437)

3.2 古英語期 (449--1100)

3.2.1 ケルト語 (##1216,2443)

3.2.2 ラテン語 (#32)

3.2.3 古ノルド語 (##2625,2693,340,818)

3.2.4 古英語本来語のその後 (##450,2556,648)

3.3 中英語期 (1100--1500)

3.3.1 フランス語 (##117,1210)

3.3.2 ラテン語 (##120,1211)

3.3.3 中英語の語彙の起源と割合 (#985)

3.4 初期近代英語期 (1500--1700)

3.4.1 ラテン語 (##478,114,1226)

3.4.2 ギリシア語 (#516)

3.4.3 ロマンス諸語 (##2385,2162,1411,1638)

3.5 後期近代英語期 (1700--1900) と現代英語期 (1900--)

3.5.1 語彙の爆発 (##203,616)

3.5.2 世界の諸言語 (##874,2165,2164)

4 現代の英語語彙にみられる歴史の遺産

4.1 フランス語とラテン語からの借用語 (#2162)

4.2 動物と肉を表わす単語 (##331,754)

4.3 語彙の3層構造 (##334,1296,335,1960)

4.4 日英語の語彙の共通点 (##1645,296,1630,1067)

5 現在そして未来の英語語彙

5.1 借用以外の新語の源泉 (##873,874,875)

5.2 語彙は時代を映し出す (##625,631,876,889)

英語語彙史を大づかみする上で最重要となる3点を指摘しておきたい.

(1) 英語語彙史は,英語と他言語の交流の歴史と連動している

(2) 語彙借用の動機づけは「必要性」のみではない

(3) 語彙借用により類義語が積み上げられていき,結果として3層構造が生じた

2017-03-05 Sun

■ #2869. 古ノルド語からの借用は古英語期であっても,その文証は中英語期 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][oe][eme]

ある言語の話者が別の言語から語を借用するという行為と,その語を常用するという慣習とは,別物である.前者はまさに「借りる」という行為が行なわれているという意味で動的な borrowing の話題であり,後者はそれが語彙体系に納まった後の静的な loan_word 使用の話題である.この2者の違いを証拠 (evidence) という観点から述べれば,文献上,前者の "borrowing" の過程は確認されることはほとんどあり得ず,後者の "loan word" 使用としての状況のみが反映されることになる.

この違いを,英語史の古ノルド語の借用(語)において考えてみよう.英語が古ノルド語の語彙を借用した時期は,両言語が接触した時期であるから,その中心は後期古英語期である.場所によっては多少なりとも初期中英語期まで入り込んでいたとしても,基本は後期古英語期であることは間違いない(「#2591. 古ノルド語はいつまでイングランドで使われていたか」 ([2016-05-31-1])).

しかし,借用という行為が後期古英語期の出来事であったとしても,そのように借用された借用語が,その時期の作とされる写本などの文献に同時代的に反映されているかどうかは別問題である.通常,借用語は社会的にある程度広く認知されるようになってから書き言葉に書き落とされるものであり,借用がなされた時期と借用語が初めて文証される時期の間にはギャップがある.とりわけ現存する後期古英語の文献のほとんどは,地理的に古ノルド語の影響が最も感じられにくい West-Saxon 方言(当時の標準的な英語)で書かれているため,古ノルド語からの借用語の証拠をほとんど示さない.一方,古ノルド語の影響が濃かったイングランド北部や東部の方言は,非標準的な方言として,もとより書き記される機会がなかったので,証拠となり得る文献そのものが残っていない.さらに,ノルマン征服以降,英語は,どの方言であれ,文献上に書き落とされる機会そのものを激減させたため,初期中英語期においてすら古ノルド語からの借用語の使用が確認できる文献資料は必ずしも多くない.したがって,多くの古ノルド語借用語が文献上に動かぬ証拠として確認されるのは,早くても初期中英語,遅ければ後期中英語以降ということになる.古ノルド語の借用(語)を論じる際に,この点はとても重要なので,銘記しておきたい.

Crowley (101) に,この点について端的に説明している箇所があるので,引いておこう.

[T]he Scandinavian influence on English dialects, which began after c. 850 and outside the tradition of writing, does not show up in any significant way in the records of Old English. The substantial pre-1066 texts from the Danelaw areas show either the local Old English dialect without Scandinavian influence or standard Late West Saxon. So, despite the circumstantial evidence and Middle English attestation of a significant Scandinavian influence, not much can be made of it for Old English.

・ Crowley, Joseph P. "The Study of Old English Dialects." English Studies 67 (1986): 97--104.

2016-08-27 Sat

■ #2679. Yiddish English における談話機能の借用 [pragmatics][borrowing][contact][semantic_borrowing][yiddish]

言語接触に伴う借用 (borrowing) は,音韻,語彙,形態,統語,意味の各部門で生じており,様々に研究されてきた.しかし,「#1988. 借用語研究の to-do list (2)」 ([2014-10-06-1]) で触れたように語用論的借用についてはいまだ研究が蓄積されていない.「#1989. 機能的な観点からみる借用の尺度」 ([2014-10-07-1]) で論じたように,談話標識 (discourse_marker) や態度を表わす小辞の借用などはあり得るし,むしろ生じやすくすらあるかもしれないと言われるが,具体的な研究事例は少ない.

少ないケーススタディの1つとして,Prince の論文を読んだ.Yiddish の背景をもつ英語変種 (Yiddish English) において,目的語や補語などを文頭にもってくる 語順が標準英語における焦点化の機能とは異なる機能で利用されている事実があり,それは Yiddish において対応する語順のもつ談話機能が借用されたものではないかという.

標準英語では,目的語や補語を頭に出す Focus-Movement は文法的である.例えば,

(1) Let's assume there's a device which can do it --- a parser let's call it.

では,let's call it の部分が旧情報として前提とされており,情報構造の観点から新情報 a parser が文頭に移動されて,焦点を得ている.

Yiddish English でみられる対応する移動 (Yiddish-Movement) でも,似たような前提と焦点化は確認されるが,少し様子が異なっている.例えば,Yiddish English から次のような例文を挙げてみよう.

(2) "Look who's here,' his wife shouted at him the moment he entered the door, the day's dirt still under his fingernails. "Sol's boy." The soldier popped up from his chair and extended his hand. "How do you do, Uncle Louis?" "A Gregory Peck," Epstein's wife said, "a Montgomery Clift your brother has. He's been here only 3 hours, already he has a date."

ここで a Montgomery Clift your brother has と移動が起こっているが,標準英語の (1) の場合と異なるところがある.両例文ともに,程度の差はあれ前提や焦点化の機能が働いていると解釈できるが,(1) では前提部分が聞き手の意識の中にある,すなわち顕著 (salient) であるのに対して,(2) では前提部分が顕著でない.したがって,標準英語の使い手にとって,(2) は語順文法として違反はしていないが,なぜ顕著でない文脈において目的語をわざわざ頭に出すのだろうと,話者の意図を理解しにくいのである.標準的な Focus-Movement と Yiddish English に特有の Yiddish-Movement では,その談話機能が若干異なっているのである.

Yiddish-Movement の談話機能の特徴は,前提部分が salient でなくても,とにかく焦点化として用いられる点にある.では,この Yiddish-Movement の談話機能はどこから来ているのかといえば,いうまでもなく Yiddish であるという.Prince (515) 曰く,". . . Yiddish-English bilinguals presumably found English Focus-Movement to be syntactically analogous to Yiddish Focus-Movement and associated with the former the discourse function of the latter."

このような談話機能の借用を定式化すると,次のようになるだろう (Prince 517) .

Given S1, a syntactic construction in one language, L1, and S2, a syntactic construction in another language, L2, the discourse function DF1 associated with S1 may be borrowed into L2 and associated with S2, just in case S1 and S2 can be construed as syntactically 'analogous' in terms of string order.

これは統語・語用的な借用とでもいうべきものだが,単語における意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) と似ていなくもない.言語において後者が広く観察されるように,前者の例も少なくないのかもしれない.

・ Prince, E. F. "On Pragmatic Change: The Borrowing of Discourse Functions." Journal of Pragmatics 12 (1988): 505--18.

2016-08-12 Fri

■ #2664. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (2) [borrowing][loan_word][semantic_borrowing][loan_translation][contact][purism]

昨日の記事 ([2016-08-11-1]) で導入した「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」の対立は,Haugen の用語である importation と substitution の対立に換言される.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) でみたように,importation とは借用元の形式をおよそそのまま自言語に取り込むことであり,substitution とは借用元の形式に対応する自言語の形式を代用することである.しかし,借用 (borrowing) と呼ばれるからには,必ず相手言語の記号の意味は得ている.その点では,オープン借用もむっつり借用も異なるところがない.

さて,この2種類の借用方法の対立を念頭に,語彙借用の比較的多いといわれる英語や日本語などの言語と,比較的少ないといわれるアイスランド語やチェコ語などの言語の差について考えてみよう.これらの言語の語彙を比較すると,なるほど,例えば英語には形態的に他言語に由来するものが多く,アイスランド語にはそのようなものが少ないことは確かである.オープン借用の多寡という点に限れば,英語は借用が多く,アイスランド語は借用が少ないという結論になる.しかし,むっつり借用を調査するとどうだろうか.もしかすると,アイスランド語は案外多く(むっつり)借用している可能性があるのではないか.むっつり借用は,表面上,借用であることが分かりにくいという特徴があるため,詳しく語源調査してみないとはっきりしたことが言えないが,その可能性は十分にある.「#903. 借用の多い言語と少ない言語」 ([2011-10-17-1]) で触れたように,「例えば借用の多いと言われる英語と少ないと言われるアイスランド語の差は,実のところ,借用の多寡そのものの差ではなく,2つの借用の方法 (importation and substitution) の比率の差である可能性があることにな」り,「両方法による借用を加え合わせたものをその言語の借用の量と考えるのであれば,一般に言われているほど諸言語間に著しい借用の多寡はないのかもしれない」とも言えるかもしれない.ひょっとすると,あらゆる言語が,スケベの種類こそ異なれ,結局のところ結構スケベ(借用好き)なのではないか.言語間にスケベ(借用好き)の程度の差がまったくないとまでは言わないが.

さらに,2種類の借用方法という観点から,他言語からの借用を嫌う言語的純粋主義 (purism) について考えてみたい.英語史にも日本語史にも,純粋主義者が他言語からの語彙借用を声高に批判する時代があった.「古き良き英語を守れ」「美しい本来の日本語を復活させよ」などと叫びながら,洪水にように迫り来る外来語に抵抗することが,歴史のなかで1度となく繰り返された.しかし,そのような純粋主義者が抵抗していたのはオープン借用に対してであり,実は彼ら自身が往々にしてむっつり借用を実践していた.現代日本語の状況で喩えれば,純粋主義の立場から「ワーキンググループ」と言わずに「作業部会」と言うべしという人がいたとすると,その人は英語の working group という記号の signifiant の借り入れにこそ抵抗しているものの,signifié については無批判に受け入れていることになる.同じスケベなら目に見えるスケベがよいという意見もあれば,同じスケベでも節度を保った目立たない立居振舞が肝要であるという意見もあろう.言語上の借用とスケベとはつくづく似ていると思う.

純粋主義と語彙借用については,「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) ,「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]),「#1545. "lexical cleansing"」 ([2013-07-20-1]),「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]),「#1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」」 ([2014-10-17-1])),「#2068. 言語への忠誠」 ([2014-12-25-1]),「#2069. 言語への忠誠,言語交替,借用方法」 ([2014-12-26-1]),「#2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判」 ([2015-03-14-1]),「#2479. 初期近代英語の語彙借用に対する反動としての言語純粋主義はどこまで本気だったか?」 ([2016-02-09-1]) などを参照.

・ Haugen, Einar. "The Analysis of Linguistic Borrowing." Language 26 (1950): 210--31.

2016-08-11 Thu

■ #2663. 「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」 (1) [borrowing][loan_word][semantic_borrowing][loan_translation][terminology][contact][sign]

標題は私の勝手に作った用語だが,言語項(特に語彙項目)の借用には大きく分けて「オープン借用」と「むっつり借用」の2種類があると考えている.

議論を簡単にするために,言語接触に際して最もよく観察される単語レベルの借用に限定して考えよう.通常,他言語から単語を借りてくるというときに起こることは,供給側の言語の単語という記号 (sign) が,多少の変更はあるにせよ,およそそのまま自言語にコピーされ,語彙項目として定着することである.記号とは,端的に言えば語義 (signifié) と語形 (signifiant) のセットであるから,このセットがそのままコピーされてくるということになる (「記号」については「#2213. ソシュールの記号,シニフィエ,シニフィアン」 ([2015-05-19-1]) を参照) .例えば,中英語はフランス語から uncle =「おじ」という語義と語形のセットを借りたし,中世後期の日本語はポルトガル語から tabaco (タバコ)=「煙草」のセットを借りた.

確かに,記号を語義と語形のセットで借り入れるのが最も普通の借用と考えられるが,語形は借りずに語義のみ借りてくる意味借用 (semantic_borrowing) や翻訳借用 (loan_translation) という過程もしばしば見受けられる.例えば,古英語 god は元来「ゲルマンの神」を意味したが,キリスト教に触れるに及び,対応するラテン語 deus のもっていた「キリスト教の神」の意味を借り入れ,自らに新たな語義を付け加えた.deus というラテン語の記号から借りたのは,語義のみであり,語形は本来語の god を用い続けたわけである(「#2149. 意味借用」 ([2015-03-16-1]),「#1619. なぜ deus が借用されず God が保たれたのか」 ([2013-10-02-1]) を参照).これは意味借用の例といえる.また,古英語がラテン語 trinitas を本来語要素からなる Þrines "three-ness" へと「翻訳」して取り入れたときも,ラテン語からは語義だけを拝借し,語形としてはラテン語をまるで感じさせないような具合に受け入れたのである.

ごく普通の借用と意味借用や翻訳借用などのやや特殊な借用との間で共通しているのは,少なくとも語義は相手言語から借り入れているということである.見栄えは相手言語風かもしれないし自言語風かもしれないが,いずれにせよ内容は相手言語から借りているのである.「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1]) でも注意を喚起した通り,この点は重要である.いずれにせよ内容は他人から借りているという点で,等しくスケベである.ただ違うのは,相手言語の語形を伴う借用(通常の借用)では借用(スケベ)であることが一目瞭然だが,相手言語の語形を伴わない借用(意味借用や翻訳借用)では借用(スケベ)であることが表面的には分からないことである.ここから,前者を「オープン借用」,後者を「むっつり借用」と呼ぶ.

はたして,どちらがよりスケベでしょうか.そして皆さんはどちらのタイプのスケベがお好みでしょうか.

2016-07-25 Mon

■ #2646. オランダ借用語に関する統計 [loan_word][borrowing][dutch][flemish][afrikaans][statistics]

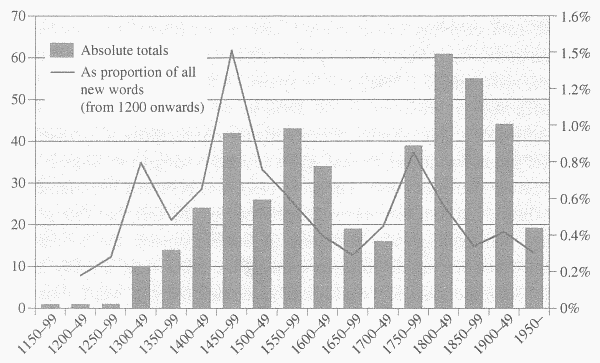

昨日の記事「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]) 及び「#148. フラマン語とオランダ語」 ([2009-09-22-1]),「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]) で取り上げてきたように,オランダ語と関連変種(フラマン語,低地ドイツ語,アフリカーンス語などを含み,オランダ語とともにすべて合わせて "Low Dutch" と呼ばれる)から英語に入った借用語は案外と多い.Durkin による OED3 による部分的な調査によれば,これらの言語からの借用語にまつわる数字を半世紀ごとにまとめると,以下のようになる (Durkin, p. 355 の "Loanwords from Dutch, Low German, and Afrikaans, as reflected by OED3 (A--ALZ and M-RZZ)" と題する表を再現した).

英語史を通じての全体的な数だけでいえば,Low Dutch からの借用語は,実に古ノルド語からの借用語よりも数が多いというのは意外かもしれない.「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]) の表では,Dutch/Flemish からの語彙的影響は "minimal" と表現されているが,実際にはもう少し高めに評価する表現であってもよさそうだ.ただし,古ノルド語ほど英語の基本語彙に衝撃を与えたわけではなく,数だけで両ケースを比較することには注意しなければならない.ただし,Low Dutch からの語彙借用に関して顕著な特徴として,中世から現代まで途切れることなく語彙を供給している点は指摘しておきたい.

時代別にみると,借用語の絶対数では中世の合計は近現代の合計を下回るが,割合としては特に後期中英語に借用が盛んだったことがよくわかる.英語本来語と Low Dutch からの借用語とは語源的,形態的に区別のつかないことも多く,実際には古英語でも少なからぬ借用があった可能性があると想像すると,Low Dutch 借用語のもつ英語史上の潜在的な意義は小さくないように思われる.

Low Dutch 借用語の統計の問題について,Durkin (356--57) は次のように議論している.

The fullest study of words of Dutch or Low German origin in English remains that of Bense (1939), who drew his data chiefly from the first edition of the the (sic) OED. Bense's study groups loanwords from Dutch and Low German together under the collective heading 'Low Dutch', although at the level of individual word histories he frequently distinguishes between input from each language. His companion work, Bense (1925), provides a summary of the main historical contexts of contact. Bense discusses over 5,000 words, for most of which he considers Low Dutch origin at least plausible; this is thus much higher than the OED's etymologies suggest. His total includes some words ultimately of Dutch origin that have definitely entered English via other languages, e.g. plaque (from a French word that ultimately has a Dutch origin), and also many semantic loans; OED3 has over 150 of these in parts so far revised, e.g. household (a. 1399) or field-cornet (1800, after South African Dutch veldkornet). Nonetheless, Bense does make a case for direct borrowing from Dutch for many words for which the OED does not posit a Dutch etymon; even if one agrees with the OED's (generally more conservative) approach in all cases, Bense's suggestions are by no means absurd, and his work highlights very well the difficulty of being certain about the extent of the Dutch contribution to the lexis of English.

5000語を超えるという Bense の試算はやや大袈裟であっても,概数としては馬鹿げていないのではないかという Durkin の評価も,なかなか印象的である.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

・ Bense, J. F. Anglo-Dutch Relations from the Earliest Times to the Death of William the Third. Den Haag: Martinus Nijhoff, 1925.

2016-07-24 Sun

■ #2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語 [loan_word][borrowing][dutch][flemish][wycliffe][etymology][onomatopoeia]

「#148. フラマン語とオランダ語」 ([2009-09-22-1]),「#149. フラマン語と英語史」 ([2009-09-23-1]) で述べたように,英語史においてオランダ語を始めとする低地帯の諸言語(方言)(便宜的に関連する諸変種を Low Dutch とまとめて指示することがある)からの語彙借用は,中英語から近代英語まで途切れることなく続いていた.その中でも12--13世紀には,イングランドとフランドルとの経済関係は羊毛の工業と取引を中心に繁栄しており,バケ (75) の言うように「ゲントとブリュージュとは,当時イングランドという羊の2つの乳房だった」.

しかし,それ以前にも,予想以上に早い時期からイングランドとフランドルの通商は行なわれていた.すでに9世紀に,アルフレッド大王はフランドル侯地の創始者ボードゥアン2世の娘エルフスリスと結婚していたし,ウィリアム征服王はボードゥアン5世の娘のマティルデと結婚している.後者の夫婦からは,後のウィリアム2世とヘンリー1世を含む息子が生まれ,さらにヘンリー1世の跡を継いだエチエンヌの母アデルという娘も生まれていた.このようにイングランドと低地帯は,交易者の間でも王族の間でも,古くから密接な関係を保っていたのである.

かくして中英語には低地帯の諸言語から多くの借用語が流入した.その単語のなかには,英語としても日本語としても馴染み深いものが少なくない.以下に中世のオランダ借用語をいくつか列挙してみたい.13世紀に「人頭」の意で入ってきた poll は,17世紀に発達した「世論調査」の意味で今日普通に用いられている.clock は,エドワード1世の招いたフランドルの時計職人により,14世紀にイングランドにもたらされた.塩漬け食品の取引から,pickle がもたらされ,ビールに欠かせない hop も英語に入った.海事関係では,13世紀に buoy が入り, 14世紀に rover, skipper が借用され,15世紀に deck, freight, hose がもたらされた.商業関係では,groat, sled が14世紀に,guilder, mart が15世紀に入っている.その他,13世紀に snatch, tackle が,14世紀に lollard が,15世紀に loiter, luck, groove, snap がそれぞれ英語語彙の一部となった.

たった今挙げた重要な単語 lollard について触れておこう.この語は,1300年頃,オランダ語で病人や貧しい人々の世話をしていた慈善団体を指していた.これが,軽蔑をこめてウィクリフの弟子たちにも適用されるようになった.彼らが詩篇や祈りを口ごもって唱えていたのを擬音語にし,あだ名にしたものともされている.英語での初例はウィクリフ派による英訳聖書が出た直後の1395年である.

・ ポール・バケ 著,森本 英夫・大泉 昭夫 訳 『英語の語彙』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1976年.

2016-07-15 Fri

■ #2636. 地域的拡散の一般性 [linguistic_area][geolinguistics][contact][language_change][causation][grammaticalisation][borrowing][sociolinguistics]

この2日間の記事(「#2634. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (1)」 ([2016-07-13-1]) と「#2635. ヨーロッパにおける迂言完了の地域言語学 (2)」 ([2016-07-14-1]))で,迂言完了の統語・意味の地域的拡散 (areal diffusion) について,Drinka の論考を取り上げた.Drinka は一般にこの種の言語項の地域的拡散は普通の出来事であり,言語接触に帰せられるべき言語変化の例は予想される以上に頻繁であると考えている.Drinka はこの立場の目立った論客であり,「#1977. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (1)」 ([2014-09-25-1]) で別の論考から引用したように,言語変化における言語接触の意義を力強く主張している.(他の論客として,Luraghi (「#1978. 言語変化における言語接触の重要性 (2)」 ([2014-09-26-1])) も参照.)

迂言完了の論文の最後でも,Drinka (28) は最後に地域的拡散の一般的な役割を強調している.

With regard to larger implications, the role of areal diffusion turns out to be essential in the development of the periphrastic perfect in Europe, throughout its history. The statement of Dahl on the role of areal phenomena is apt here:

Man kann wohl sagen, dass Sprachbundphänomene in Grammatikalisierungsproessen eher die Regel als eine Ausnahme sind---solche Prozesse verbreiten sich oft zu mehreren benachbarten Sprachen und schaffen dadurch Grammfamilien. (Dahl 1996:363)

Not only are areally-determined distributions frequent and widespread, but they constitute the essential explanation for the introduction of innovation in many cases.

このような地域的拡散という話題は,言語圏 (linguistic_area) という概念とも密接な関係にある.特に迂言完了のような統語的な借用 (syntactic borrowing) については,「#1503. 統語,語彙,発音の社会言語学的役割」 ([2013-06-08-1]) で触れたように,社会の団結の標識 (the marker of cohesion in society) と捉えられる可能性が指摘されており,社会言語学における遠大な仮説を予感させる.

なお,言語内的な要因と言語外的な要因を巡る議論は,本ブログでも多く取り上げてきた.「#2589. 言語変化を駆動するのは形式か機能か (2)」 ([2016-05-29-1]) に関連する諸記事へのリンク集を挙げているので,そちらを参照されたい.

・ Drinka, Bridget. "Areal Factors in the Development of the European Periphrastic Perfect." Word 54 (2003): 1--38.

2016-07-04 Mon

■ #2625. 古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性 [old_norse][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

古ノルド語からの借用語には,基礎的で日常的な語彙が多く含まれていることはよく知られている.「#340. 古ノルド語が英語に与えた影響の Jespersen 評」 ([2010-04-02-1]) では,この事実を印象的に表現する Jespersen の文章を引用した.

今回は,現代英語の基礎語彙を構成しているとみなすことのできる古ノルド語からの借用語を列挙しよう.ただし,ここでいう「基礎語彙」とは,Durkin (213) が "we can identify fairly impressionistically the following items as belonging to contemporary everyday vocabulary, familiar to the average speaker of modern English" と述べているように,英語母語話者が直感的に基礎的と認識している語彙のことである.

・ pronouns: they, them, their

・ other function words: both, though, (probably) till; (archaic or regional) fro, (regional) mun

・ verbs that realize very basic meanings: die, get, give, hit, seem, take, want

・ other familiar items of everyday vocabulary (impressionistically assessed): anger, awe, awkward, axle, bait, bank (of earth), bask, bleak, bloom, bond, boon, booth, boulder, bound (for), brink, bulk, cake, calf (of the leg), call, cast, clip (= cut), club (= stick), cog, crawl, dank, daze, dirt, down (= feathers), dregs, droop, dump, egg, to egg (on), fellow, flat, flaw, fling, flit, gap, gape, gasp, gaze, gear, gift, gill, glitter, grime, guest, guild, hail (= greet), husband, ill, kettle, kid, law, leg, lift, link, loan, loose, low, lug, meek, mire, muck, odd, race (= rush, running), raft, rag, raise, ransack, rift, root, rotten, rug, rump, same, scab, scalp, scant, scare, score, scowl, scrap, scrape, scuffle, seat, sister, skill, skin, skirt, skulk, skull, sky, slant, slug, sly, snare, stack, steak, thrive, thrust, (perhaps) Thursday, thwart, ugly, wand, weak, whisk, window, wing, wisp, (perhaps) wrong.

なお,この一覧を掲げた Durkin (213) の断わり書きも付しておこう."Of course, it must be remembered that in many of these cases it is probable that a native cognate has been directly replaced by a very similar-sounding Scandinavian form and we may only wish to see this as lexical borrowing in a rather limited sense."

古ノルド語からの借用語の日常性は,しばしば英語と古ノルド語の言語接触の顕著な特異性を示すものとして紹介されるが,言語接触の類型論の立場からは,いわれるほど特異ではないとする議論もある.後者については,「#1182. 古ノルド語との言語接触はたいした事件ではない?」 ([2012-07-22-1]),「#1183. 古ノルド語の影響の正当な評価を目指して」 ([2012-07-23-1]),「#1779. 言語接触の程度と種類を予測する指標」 ([2014-03-11-1]) を参照されたい.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-30 Thu

■ #2621. ドイツ語の英語への本格的貢献は19世紀から [loan_word][borrowing][statistics][german]

「#2164. 英語史であまり目立たないドイツ語からの借用」 ([2015-03-31-1]) で触れたように,ドイツ語の英語への語彙的影響は案外少ない.安井・久保田 (20) は次のように述べている.

ドイツ語が1824年に至るまで,英国人に,ほとんどまったくといってよいくらい,顧みられなかったのも,驚くべきことである.ドイツ語からの借用語は16世紀からあるにはあるが,フランス語,オランダ語,スカンジナヴィア語などよりの借用語に比べると,じつに少ないのである.20世紀に入ってからでも,英国人のドイツ語に関する知識は満足すべき段階に達していない.

なお,引用中の1824年とは,Thomas Carlyle (1795--1881) が Göthe の Wilhelm Meister's Apprenticeship を翻訳出版した年である.

OED3 により借用語を研究した Durkin (362) によると,19世紀より前にはドイツ借用語は目立っていなかったが,19世紀前半に一気に伸張したという.19世紀後半にはその勢いがピークに達し,20世紀前半に半減した後,20世紀後半にかけて下火となるに至る. *

ドイツ借用語は全体として専門用語が多く,それが一般に目立たない理由だろう.Durkin (361) は Pfeffer and Cannon の先行研究を参照しながら,ドイツ語借用の性質と時期について次のように要約している.

Pfeffer and Cannon provide a broad analysis of their data into subject areas; those with the highest numbers of items are (in descending order) mineralogy, chemistry, biology, geology, botany; only after these do we find two areas not belonging to the natural sciences: politics and music. The remaining areas that have more than a hundred items each (including semantic borrowings) are medicine, biochemistry, philosophy, psychology, the military, zoology, food, physics, and linguistics. Nearly all of these semantic areas reflect the importance of German as a language of culture and knowledge, especially in the latter part of the nineteenth century and early twentieth century.

英語はゲルマン系 (Germanic) の言語であり,ドイツ語 (German) と「系統」関係にあるとは言えるが,上に見たように両言語は歴史的に(近現代に至ってすら)接触の機会が意外と乏しかったために,「影響」関係は僅少である.たまに「英語はドイツ語の影響を受けている」と言う人がいるが,これは系統関係と影響関係を取り違えているか,あるいは Germanic と German を同一視しているか,いずれにせよ誤解に基づいている.この誤解については「#369. 言語における系統と影響」 ([2010-05-01-1]),「#1136. 異なる言語の間で類似した語がある場合」 ([2012-06-06-1]),「#1930. 系統と影響を考慮に入れた西インドヨーロッパ語族の関係図」 ([2014-08-09-1]) を参照.

・ 安井 稔・久保田 正人 『知っておきたい英語の歴史』 開拓社,2014年.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-24 Fri

■ #2615. 英語語彙の世界性 [lexicology][loan_word][borrowing][statistics][link]

英語語彙は世界的 (cosmopolitan) である.350以上の言語から語彙を借用してきた歴史をもち,現在もなお借用し続けている.英語語彙の世界性とその歴史について,以下に本ブログ (http://user.keio.ac.jp/~rhotta/hellog/) 上の関連する記事にリンクを張った.英語語彙史に関連するリンク集としてどうぞ.

1 数でみる英語語彙

1.1 語彙の規模の大きさ (#45)

1.2 語彙の種類の豊富さ (##756,309,202,429,845,1202,110,201,384)

2 語彙借用とは?

2.1 なぜ語彙を借用するのか? (##46,1794)

2.2 借用の5W1H:いつ,どこで,何を,誰から,どのように,なぜ借りたのか? (#37)

3 英語の語彙借用の歴史 (#1526)

3.1 大陸時代 (--449)

3.1.1 ラテン語 (#1437)

3.2 古英語期 (449--1100)

3.2.1 ケルト語 (##1216,2443)

3.2.2 ラテン語 (#32)

3.2.3 古ノルド語 (##340,818)

3.3 中英語期 (1100--1500)

3.3.1 フランス語 (##117,1210)

3.3.2 ラテン語 (#120)

3.4 初期近代英語期 (1500--1700)

3.4.1 ラテン語 (##114,478)

3.4.2 ギリシア語 (#516)

3.4.3 ロマンス諸語 (#2385)

3.5 後期近代英語期 (1700--1900) と現代英語期 (1900--)

3.5.1 世界の諸言語 (##874,2165)

4 現代の英語語彙にみられる歴史の遺産

4.1 フランス語とラテン語からの借用語 (#2162)

4.2 動物と肉を表わす単語 (##331,754)

4.3 語彙の3層構造 (##334,1296,335)

4.4 日英語の語彙の共通点 (##1526,296,1630,1067)

5 現在そして未来の英語語彙

5.1 借用以外の新語の源泉 (##873,875)

5.2 語彙は時代を映し出す (##625,631,876,889)

[ 参考文献 ]

・ Hughes, G. A History of English Words. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-06-04 Sat

■ #2595. 英語の曜日名にみられるローマ名の「借用」の仕方 [latin][etymology][borrowing][loan_word][loan_translation][mythology][calendar]

現代英語の曜日の名前は,よく知られているように,太陽系の主要な天体あるいは神話上それと結びつけられた神の名前を反映している.いずれも,ラテン単語の反映であり,ある意味で「借用」といってよいが,その借用の仕方に3つのパターンがみられる.

Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday については,各々の複合語の第1要素として,ローマ神 Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, Venus に対応するゲルマン神の名前が与えられている.これは,ローマ神話の神々をゲルマン神話の神々で体系的に差し替えたという点で,"loan rendition" と呼ぶのがふさわしいだろう.(Wednesday については「#1261. Wednesday の発音,綴字,語源」 ([2012-10-09-1]) を参照.)

一方,Sunday, Monday の第1要素については,それぞれ太陽と月という天体の名前をラテン語から英語へ翻訳したものと考えられる.差し替えというよりは,形態素レベルの翻訳 "loan translation" とみなしたいところだ.

最後に Saturday の第1要素は,ローマ神話の Saturnus というラテン単語の形態をそのまま第1要素へ借用してきたので,第1要素のみに限定すれば,ここで生じたことは通常の借用 ("loan") である(複合語全体として考える場合には,第1要素が借用,第2要素が本来語なので "loanblend" の例となる;see 「#901. 借用の分類」 ([2011-10-15-1])).

英語の曜日名に,上記のように「借用」のいくつかのパターンがみられることについて,Durkin (106) が次のように紹介しているので,引用しておきたい.

The modern English names of six of the days of the week reflect Old English or (probably) earlier loan renditions of classical or post-classical Latin names; the seventh, Saturday, shows a borrowed first element. In the cases of Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday there is substitution of the names of roughly equivalent pagan Germanic deities for the Roman ones, with the names of Tiw, Woden, Thunder or Thor, and Frig substituted for Mars, Mercury, Jupiter, and Venus respectively; in the cases of Monday and Sunday the vernacular names of the celestial bodies Moon and Sun are substituted for the Latin ones. The first element of Saturday (found in Old English in the form types Sæternesdæġ, Sæterndæġ, Sætresdæġ, and Sæterdæġ) uniquely shows borrowing of the Latin name of the Roman deity, in this case Saturn.

・ Durkin, Philip. Borrowed Words: A History of Loanwords in English. Oxford: OUP, 2014.

2016-05-18 Wed

■ #2578. ケルト語を通じて英語へ借用された一握りのラテン単語 [loan_word][latin][celtic][oe][borrowing][statistics]

ブリテン島が紀元43年から410年までのあいだローマの支配化に置かれ,島内である程度ラテン語が話されていたという事実から,この時期に用いられていたラテン単語が,後に島内の主たる言語となる英語にも,相当数残っているはずではないかと想像されるかもしれない.当時のラテン単語の多くが,ケルト語話者が媒介となって,後に英語にも伝えられたのではないかと.しかし,実際にはそのような状況は起こらなかった.Baugh and Cable (77) によると,

It would be hardly too much to say that not five words outside of a few elements found in place-names can be really proved to owe their presence in English to the Roman occupation of Britain. It is probable that the use of Latin as a spoken language did not long survive the end of Roman rule in the island and that such vestiges as remained for a time were lost in the disorders that accompanied the Germanic invasions. There was thus no opportunity for direct contact between Latin and Old English in England, and such Latin words as could have found their way into English would have had to come in through Celtic transmission. The Celts, indeed, had adopted a considerable number of Latin words---more than 600 have been identified--- but the relations between the Celts and the English were such . . . that these words were not passed on.

当時のケルト語には600語近くラテン単語が入っていたというのは,知らなかった.さて,古英語に入ったのはきっかり5語にすぎないといっているが,Baugh and Cable (77--78) が挙げているのは,ceaster (< L castra "camp"), port (< L portus, porta "harbor, gate, town"), munt (< L mōns, montem "mountain"), torr (L turris "tower, rock"), wīc (< L vīcus "village") である.これですら語源に異説のあるものもあり,ケルト語経由で古英語に入ったラテン借用語の確実な例とはならないかもしれない.その他,地名要素としての street, wall, wine などが加えられているが,いずれにせよそのようなルートで古英語に入ったラテン借用語一握りしかない.

「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1]),「#1437. 古英語期以前に借用されたラテン語の例」 ([2013-04-03-1]),「#1945. 古英語期以前のラテン語借用の時代別分類」 ([2014-08-24-1]) などで触れたように,英語史においてラテン単語の借用の波と経路は何度かあったが,この Baugh and Cable の呼ぶところのラテン単語借用の第1期に関しては,見るべきものが特に少ないと言っていいだろう.Baugh and Cable (78) の結論を引こう.

At best . . . the Latin influence of the First Period remains much the slightest of all the influences that Old English owed to contact with Roman civilization.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow