2026-02-16 Mon

■ #6139. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第10回「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」をマインドマップ化してみました [asacul][mindmap][notice][intensifier][adverb][semantic_change][lexicology][onomasiology][kdee][hee][etymology][french][loan_word][borrowing][hel_education][helkatsu][conversion][synonym]

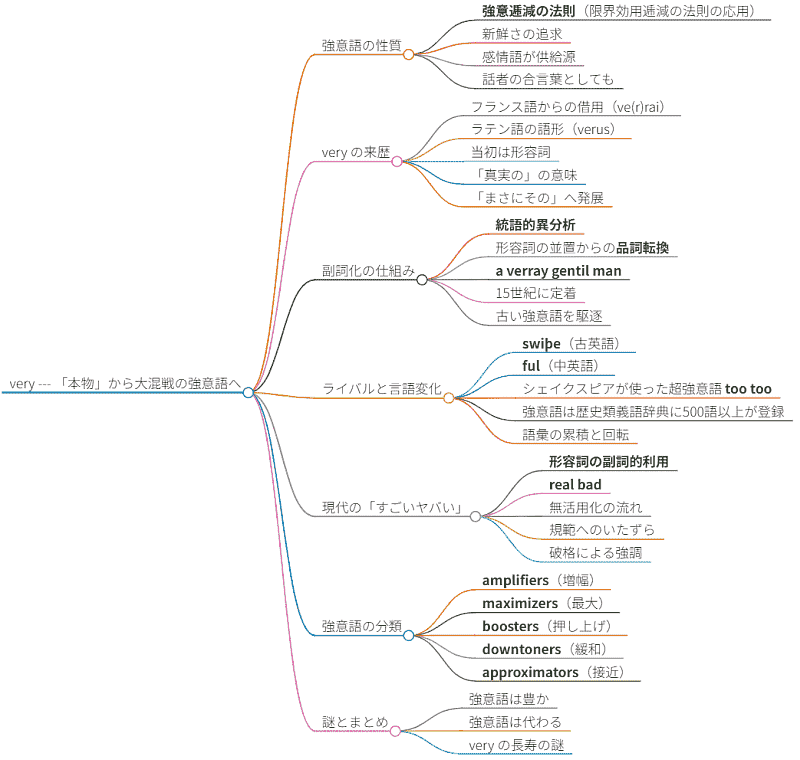

1月31日(土)に,今年度の朝日カルチャーセンターのシリーズ講座「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」の第10回が,冬期クールの第1回として開講されました.テーマは「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」でした.

very といえば,最も日常的で無標な強意語 (intensifier) と認識されていると思います,あまりに卑近な単語なので深く考えたこともないかもしれませんが,英語史的にも様々な観点から議論できる,話題の尽きない語彙項目です.講義では,very の起源と発展をたどり,他の類義語と比較し,強意語という語類の特異な性質に迫りました.濃密な90分となったと思います.

この朝カル講座第10回の内容を markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました.復習用にご参照いただければ.

なお,この朝カル講座のシリーズの第1回から第8回についてもマインドマップを作成してるので,そちらもご参照ください.

・ 「#5857. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第1回「she --- 語源論争の絶えない代名詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-05-10-1])

・ 「#5887. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第2回「through --- あまりに多様な綴字をもつ語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-06-09-1])

・ 「#5915. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第3回「autumn --- 類義語に揉み続けられてきた季節語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-07-07-1])

・ 「#5949. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第4回「but --- きわめつきの多義の接続詞」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-08-10-1])

・ 「#5977. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第5回「guy --- 人名からカラフルな意味変化を遂げた語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-09-07-1])

・ 「#6013. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第6回「English --- 慣れ親しんだ単語をどこまでも深掘りする」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-10-01-1])

・ 「#6041. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第7回「I --- 1人称単数代名詞をめぐる物語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-11-10-1])

・ 「#6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-12-15-1])

・ 「#6076. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第8回「take --- ヴァイキングがもたらした超基本語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2025-12-15-1])

・ 「#6098. 2025年度の朝カルシリーズ講座の第9回「one --- 単なる数から様々な用法へ広がった語」をマインドマップ化してみました」 ([2026-01-06-1])

次回の第11回は2月28日(土)で,主題は「that --- 指示詞から多機能語への大出世」となります.開講形式は引き続きオンラインのみで,開講時間は 15:30--17:00 です.ご関心のある方は,ぜひ朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室の公式HPより詳細をご確認の上,お申し込みいただければ幸いです.

2026-01-24 Sat

■ #6116. 1月31日(土),朝カル講座の冬期クール第1回「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」が開講されます [asacul][notice][intensifier][adverb][semantic_change][lexicology][onomasiology][kdee][hee][etymology][french][loan_word][borrowing][hel_education][helkatsu][conversion][synonym]

今年度は月1回,朝日カルチャーセンター新宿教室で英語史講座を開いています.シリーズタイトルは「歴史上もっとも不思議な英単語」です.英語史的に厚みと含蓄のある英単語を1つ選び,そこから説き起こして,『英語語源辞典』(研究社)や『英語語源ハンドブック』(研究社)等の記述を参照しながら,その英単語の歴史,ひいては英語全体の歴史を語ります.

1週間後,1月31日(土)の講座は冬期クールの初回となります.今回取り上げるのは,英語学習者にとって(そして多くの英語話者にとっても)最も馴染み深い副詞の1つでありながら,その来歴に驚くべき変遷を隠し持っている very です.

私たちは普段,何気なく「とても,非常に」という意味で very を使っています.機能語に近い役割を果たす,ごくありふれた単語です.しかし,英語史の観点からこの語を眺めると,そこには「強調」という人間心理につきまとう,激しい生存競争の歴史が見えてきます.以下,very をめぐって取り上げたい論点をいくつか挙げてみます.

・ 高頻度語の very は,実は英語本来語ではなく,フランス語からの借用語です.なぜこのような基礎的な単語が借用されるに至ったのでしょうか.

・ フランス語ではもともと「真実の」を意味する形容詞 (cf. Fr. vrai) であり,英語に入ってきた当初も形容詞として用いられていました.the very man 「まさにその男」などの用法にその痕跡が残っています.これがいかなるきっかけで強意の副詞となり,しかもここまで高頻度になったのでしょうか.

・ 強意語には「強意逓減の法則」という語彙論・意味論上の宿命があります.強調表現は使われすぎると手垢がつき,強調の度合いがすり減ってしまうのです.

・ 英語史を通じて,おびただしい強意語が現われては消えていきました.古英語や中英語で使われていた代表的な強意語を覗いてみます.

・ 多くの強意語が消えゆく(あるいは陳腐化する)なかで,なぜ very は生き残り,さらに現代英語においてこれほどの安定感を示しているのでしょうか.大きな謎です.

・ 一般的に「強調」とは何か,「強意語」とは言語においてどのような位置づけにあるのかについても考えてみたいと思います.

このように,very という一見単純な単語の背後に,形容詞から副詞への品詞転換,意味の漂白化,そして類義語との競合といった,英語語彙史上ののエッセンスが詰まっています.このエキサイティングな歴史を90分でお話しします.

講座への参加方法は,今期もオンライン参加のみとなります.リアルタイムでの受講のほか,2週間の見逃し配信サービスもあります.皆さんのご都合のよい方法でご参加いただければ幸いです.開講時間は 15:30--17:00 となっています.講座と申込みの詳細は朝カルの公式ページよりご確認ください.

なお,冬期クールのラインナップは以下の通りです.2026年の幕開けも,皆さんで英語史を楽しく学んでいきましょう!

- 第10回:1月31日(土) 15:30?17:00 「very --- 「本物」から大混戦の強意語へ」

- 第11回:2月28日(土) 15:30?17:00 「that --- 指示詞から多機能語への大出世」

- 第12回:3月28日(土) 15:30?17:00 「be --- 英語の「存在」を支える超不規則動詞」

・ 寺澤 芳雄(編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』新装版 研究社,2024年.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2023-07-01 Sat

■ #5178. 名義論的変化の2つのタイプ [lexicology][semantic_change][homonymic_clash][semantics][synonym][semiotics][onomasiology]

昨日の記事「#5177. 語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology)」 ([2023-06-30-1]) で取り上げたように,意味変化 (semantic_change or semasiological change) とともに扱われることが多いが,明確に区別すべき過程として名義論的変化 (onomasiological change) というものがある.

Traugott and Dasher (52--53) は,名義論的変化 ("onomasiological changes") について,Bréal の議論を参照する形で,2つのタイプを挙げている.

(i) Specialization: one element "becomes the pre-eminent exponent of the grammatical conception of which it bears the stamp" . . . , for example, the selection of que as the sole complementizer in French . . . .

(ii) Differentiation: two elements which are (near-)synonymous diverge. Paradigm examples include, in English, (a) the specialization, e.g. of hound when dog was borrowed from Scandinavian, and (b) loss of a form when sound change leads to "homonymic clash," e.g. ME let in the sense "prohibit" from OE lett- was lost after OE lætan "allow" also developed into ME let . . . .

Bréal によれば,名義論的変化は,意味変化の話題でないばかりか,単純に名前の変化というわけでもなく,"the proper subject of the 'science of significations'" (95) ということらしい.

正直にいうと,Bréal の説明は込み入っており理解しにくい.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth C. and Richard B. Dasher. Regularity in Semantic Change. Cambridge: CUP, 2005.

・ Bréal, Michel. Semantics: Studies in the Science of Meaning. Trans. Mrs. Henry Cust. New York: Dover, 1964. 1900.

2023-06-30 Fri

■ #5177. 語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) [lexicology][semantic_change][semantics][semiotics][onomasiology][terminology]

語の意味変化 (semantic_change) を論じる際に,語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) を分けて考える必要がある.堀田 (155) より引用する.

語の意味変化を考えるに当たっては,語義論 (semasiology) と名義論 (onomasiology) を区別しておきたい.語を意味と発音の結びついた記号と考えるとき,発音(名前)を固定しておき,その発音に結びつけられる意味が変化していく様式を,語義論的変化と呼ぶ.一方,意味の方を固定しておき,その意味に結びつけられる名前が変化していく様式を名義論的変化と呼ぶ.語の意味変化を,記号の内部における結びつき方の変化として広義に捉えるならば,語義論的な変化のみならず名義論的な変化をも考慮に入れてよいだろう.

要するに,語義論は通常の意味変化,名義論は名前の変化と理解しておけばよい.「#3283. 『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]が出版されました」 ([2018-04-23-1]) を参照.

・ 堀田 隆一 「第8章 意味変化・語用論の変化」『歴史言語学』朝倉日英対照言語学シリーズ[発展編]3 服部 義弘・児馬 修(編),朝倉書店,2018年.151--69頁.

2021-12-31 Fri

■ #4631. Oxford Bibliographies による意味・語用変化研究の概要 [hel_education][history_of_linguistics][bibliography][semantic_change][semantics][pragmatics][oxford_bibliographies][onomasiology]

分野別に整理された書誌を専門家が定期的にアップデートしつつ紹介してくれる Oxford Bibliographies より,"Semantic-Pragmatic Change" の項目を参照した(すべてを読むにはサブスクライブが必要).この分野の重鎮といえる Elizabeth Closs Traugott による選で,最新の更新は2020年12月8日となっている.副題に "Your Best Research Starts Here" とあり入門的書誌を予想するかもしれないが,実際には専門的な図書や論文も多く含まれている. *

今回はそのイントロを引用し,この分野の研究のあらましを紹介するにとどめる.

Semantic change is the subfield of historical linguistics that investigates changes in sense. In 1892, the German philosopher Gottlob Frege argued that, although they refer to the same person, Jocasta and Oedipus's mother, are not equivalent because they cannot be substituted for each other in some contexts; they have different "senses" or "values." In contemporary linguistics, most researchers agree that words do not "have" meanings. Rather, words are assigned meanings by speakers and hearers in the context of use. These contexts of use are pragmatic. Therefore, semantic change cannot be understood without reference to pragmatics. It is usually assumed that language-internal pragmatic processes are universal and do not themselves change. What changes is the extent to which the processes are activated at different times, in different contexts, in different communities, and to which they shape semantic and grammatical change. Many linguists distinguish semantic change from change in "lexis" (vocabulary development, often in cultural contexts), although there is inevitably some overlap between the two. Semantic changes occur when speakers attribute new meanings to extant expressions. Changes in lexis occur when speakers add new words to the inventory, e.g., by coinage ("affluenza," a blend of affluent and influenza), or borrowing ("sushi"). Linguists also distinguish organizing principles in research. Starting with the form of a word or phrase and charting changes in the meanings of that the word or phrase is known as ???semasiology???; this is the organizing principle for most historical dictionaries. Starting with a concept and investigating which different expressions can express it is known as "onomasiology"; this is the organizing principle for thesauruses.

意味・語用変化の私家版の書誌としては,3ヶ月ほど前に「#4544. 英単語の意味変化と意味論を研究しようと思った際の取っ掛かり書誌(改訂版)」 ([2021-10-05-1]) を挙げたので,そちらも参照されたい.

皆様,今年も「hellog?英語史ブログ」のお付き合い,ありがとうございました.よいお年をお迎えください.

2019-01-23 Wed

■ #3558. 言語と言語名の記号論 [world_languages][sociolinguistics][dialect][variety][scots_english][celtic][onomasiology]

ある言語を何と呼ぶか,あるいはある言語名で表わされている言語は何かという問題は,社会言語学的に深遠な話題である.言語名と,それがどの言語を指示するかという記号論的関係の問題である.

日本の場合,アイヌ語や八重山語などの少数言語がいくつかあることは承知した上で,事実上「言語名=母語話者名=国家名=民族名」のように諸概念の名前が「日本」できれいに一致するので,言語を「日本語」と呼ぶことに何も問題がないように思われるかもしれない(cf. 「#3457. 日本の消滅危機言語・方言」 ([2018-10-14-1])).しかし,このように諸概念名がほぼ一致する言語は,世界では非常に珍しいということを知っておく必要がある.

アジア,アフリカ,太平洋地域はもとより,意外に思われるかもしれないがヨーロッパ諸国でも言語,母語話者,国家,民族は一致せず,したがってそれらを何と呼称するかという問題は,ときに深刻な問題になり得るのだ(cf. 「#1374. ヨーロッパ各国は多言語使用国である」 ([2013-01-30-1])).たとえば,本ブログでは「#1659. マケドニア語の社会言語学」 ([2013-11-11-1]) や「#3429. マケドニアの新国名を巡る問題」 ([2018-09-16-1]) でマケドニア(語)について論じてきたし,「#1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian」 ([2013-10-19-1]) では旧ユーゴの諸言語の名前を巡る話題も取り上げてきた.

本ブログの関心から最も身近なところでいえば,「英語」という呼称が指すものも時代とともに変化してきた.古英語期には,"English" はイングランドで話されていた西ゲルマン語群の諸方言を集合的に指していた.しかし,中英語期には,この言語の話者はイングランド以外でも,部分的にではあれスコットランド,ウェールズ,アイルランドでも用いられるようになり,"English" の指示対象は地理的も方言的にも広まった.さらに近代英語期にかけては,英語はブリテン諸島からも飛び出して,様々な変種も含めて "English" と呼ばれるようになり,現代ではアメリカ英語やインド英語はもとより世界各地で行なわれているピジン英語までもが "English" と呼ばれるようになっている.「英語」の記号論的関係は千年前と今とでは著しく異なっている.

前段の話題は "English" という名前の指す範囲の変化についての semasiological な考察だが,逆に A と呼ばれていたある言語変種が,あるときから B と呼ばれるようになったという onomasiological な例も挙げておこう.「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) で紹介した通り,スコットランド低地地方に根付いた英語変種は,15世紀以前にはあくまで "Inglis" の1変種とみなされていたが,15世紀後半から "Scottis" と称されるようになったのである.この "Scottis" とは,本来,英語とは縁もゆかりもないケルト語派に属するゲール語を指していたにもかかわらずである.平田 (57) が指摘する通り,このような言語名の言い換えの背景には,必ずやその担い手のアイデンティティの変化がある.

古スコッツ語は,一一〇〇年から一七〇〇年まで初期スコッツ語,中期スコッツ語と変遷した歴史を持つが,もっとも大きな変化は,一五世紀末に呼び名が変わったこと,すなわちイングリスがスコティス(Scottis は Scottish の古スコッツ語異形.Scots は Scottis の中間音節省略形)と呼ばれるようになったことである.かつてスコティスという言葉はあきらかにハイランド(とアイルランド)のゲール語を指していた.スコットランド性はゲール語と結びつけられていた.ところが,ローランド人は,この言語変種の呼び名はスコティスであると主張した.これははっきりとした自己認識の転換であった.スコティスはこれ以後はゲール語以外の言語を指すようになった.これはスコットランドの言語的なアイデンティティが転換したことを示しているのである.

言語と言語名の記号論ほど,すぐれて社会言語学的な話題はない.

・ 平田 雅博 『英語の帝国 ―ある島国の言語の1500年史―』 講談社,2016年.

2018-02-20 Tue

■ #3221. 意味変化の不可避性 [semantic_change][semantics][esperanto][artificial_language][onomasiology]

Algeo and Pyles は,語の意味の変化を論じた章の最後で,意味変化の不可避性を再確認している.そこで印象的なのは,Esperanto などの人工言語の話題を持ち出しながら,そのような言語的理想郷と意味変化の不可避性が相容れないことを熱く語っている点だ.少々長いが,"SEMANTIC CHANGE IS INEVITABLE" と題する問題の節を引用しよう (243--44) .

It is a great pity that language cannot be the exact, finely attuned instrument that deep thinkers wish it to be. But the facts are, as we have seen, that the meaning of practically any word is susceptible to change of one sort or another, and some words have so many individual meanings that we cannot really hope to be absolutely certain of the sum of these meanings. But it is probably quite safe to predict that the members of the human race, homines sapientes more or less, will go on making absurd noises with their mouths at one another in what idealists among them will go on considering a deplorably sloppy and inadequate manner, and yet manage to understand one another well enough for their own purposes.

The idealists may, if they wish, settle upon Esperanto, Ido, Ro, Volapük, or any other of the excellent scientific languages that have been laboriously constructed. The game of construction such languages is still going on. Some naively suppose that, should one of these ever become generally used, there would be an end to misunderstanding, followed by an age of universal brotherhood---the assumption being that we always agree with and love those whom we understand, though the fact is that we frequently disagree violently with those whom we understand very well. (Cain doubtless understood Abel well enough.)

But be that as it may, it should be obvious, if such an artificial language were by some miracle ever to be accepted and generally used, it would be susceptible to precisely the kind of changes in meaning that have been our concern in this chapter as well as to such change in structure as have been our concern throughout---the kind of changes undergone by those natural languages that have evolved over the eons. And most of the manifold phenomena of life---hatred, disease, famine, birth, death, sex, war, atoms, isms, and people, to name only a few---would remain as messy and hence as unsatisfactory to those unwilling to accept them as they have always been, no matter what words we use in referring to them.

私の好きなタイプの文章である.なお,引用の最後で "no matter what words we use in referring to them" と述べているのは,onomasiological change/variation に関することだろう.Algeo and Pyles は,semasiological change と onomasiological change を合わせて,広く「意味変化」ととらえていることがわかる.

人工言語の抱える意味論上の問題点については,「#961. 人工言語の抱える問題」 ([2011-12-14-1]) の (4) を参照.関連して「#963. 英語史と人工言語」 ([2011-12-16-1]) もどうぞ.また,「#1955. 意味変化の一般的傾向と日常性」 ([2014-09-03-1]) もご覧ください.

・ Algeo, John, and Thomas Pyles. The Origins and Development of the English Language. 5th ed. Thomson Wadsworth, 2005.

2015-04-13 Mon

■ #2177. 伝統的な意味変化の類型への批判 (2) [semantic_change][semantics][folk_etymology][prediction_of_language_change][onomasiology]

「#2175. 伝統的な意味変化の類型への批判」 ([2015-04-11-1]) の記事に補足したい.McMahon (184--86) は,意味変化を扱う章で,やはり伝統的な意味変化の類型を概説しながらも,それに対する批判を繰り広げている.前回の記事と重なる内容が多いが,McMahon の議論を聞いてみよう.

まず,伝統的な意味変化の類型においては,一般化 (generalization),特殊化 (specialization),悪化 (pejoration),良化 (amelioration) のほかメタファー (metaphor),メトニミー (metonymy),省略 (ellipsis),民間語源 (folk_etymology) などのタイプがしばしば区別されるが,最後の2つは厳密には意味変化の種類ではない.意味にも間接的に影響を及ぼす形態の変化というべきものであり,せいぜい二次的な意味における意味変化にすぎない.換言すれば,これらは semasiological というよりは onomasiological な観点に関するものである.この点については,「#2174. 民間語源と意味変化」 ([2015-04-10-1]) でも批判的に論じた.

次に,複数の意味変化の種類が共存しうることである.例えば,民間語源の例としてしばしば取り上げられる現代英語の belfry (bell-tower) では,鐘 (bell) によって鐘楼を代表する "pars pro toto" のメトニミー(あるいは提喩 (synecdoche))も作用している.この意味変化を分類しようとすれば,民間語源でもあり,かつメトニミーでもあるということになり,もともとの類型が水も漏らさぬ盤石な類型ではないことを露呈している.このことはまた,意味変化の原因やメカニズムが極めて複雑であること,そして予測不可能であることを示唆する.

最後に,従来挙げられてきた類型によりあらゆる意味変化の種類が挙げ尽くされたわけではなく,網羅性が欠けている.もっとも意味変化の種類をでたらめに増やしていけばよいというものでもないし,そもそも類型として整理しきることができるのかという問題はある.

結局のところ,類型の構築が難しいのは,(1) 意味変化が社会や文化を参照しなければ記述・説明ができないことが多く,(2) 不規則で予測不可能であり,(3) 共時的意味論の理論的基盤が(共時的音韻論などよりも)いまだ弱い点に帰せられるように思われる.

・ McMahon, April M. S. Understanding Language Change. Cambridge: CUP, 1994.

2014-10-18 Sat

■ #2000. 歴史語用論の分類と課題 [historical_pragmatics][pragmatics][history_of_linguistics][philology][onomasiology]

「#545. 歴史語用論」 ([2010-10-24-1]),「#1991. 歴史語用論の発展の背景にある言語学の "paradigm shift"」 ([2014-10-09-1]) で,近年の歴史語用論 (historical_pragmatics) の発展を話題にした.今回は,芽生え始めている歴史語用論の枠組みについて Jucker に拠りながら略述する.まずは,Jucker (110) による歴史語用論の定義から([2010-10-24-1]に挙げた Taavitsainen and Fitzmaurice による定義も参照).

Historical pragmatics (HP) is a field of study that investigates pragmatic aspects in the history of specific languages. It studies various aspects of language use at earlier stages in the development of a language; it studies the diachronic development of language use; and it studies the pragmatic motivations for language change.

一見すると雑多な話題,従来の主流派言語学からは「ゴミ」とすら見られてきたような話題を,歴史的に扱う分野ということになる.歴史言語学は,研究者の関心や力点の置き方にしたがって,方向性が大きく2つに分かれるとされる (Jucker 110--11) .Jacobs and Jucker の分類によれば,次の通り.

(1) pragmaphilology

(2) diachronic pragmatics

a) diachronic form-to-function mapping

b) diachronic function-to-form mapping

まず,歴史語用論の「歴史」のとらえ方により,過去のある時代を共時的にみるか (pragmaphilology) ,あるいは時間軸に沿った発達を,つまり通時的な発展をみるか (diachronic pragmatics) に分けられる.後者はさらに,ある形態を固定してその機能の通時的な変化をみるか (diachronic form-to-function mapping),逆に機能を固定して対応する形態の通時的な変化をみるか (diachronic function-to-form mapping) に分けられる(記号論的には semasiology と onomasiology の対立に相当する).

上記の Jacobs and Jucker の分類と名付けは,Huang が "European Continental view" あるいは "perspective view" と呼ぶ語用論のとらえ方を反映している.そこでは,語用論は,言語能力を構成する部門の1つとしてではなく,言語行動のあらゆる側面に関与するコミュニケーション機能として広く解されている.この流れを汲む歴史語用論は,文献学的な色彩が強い.

一方,Huang が "Anglo-American view" あるいは "component view" と呼ぶ語用論のとらえ方がある.そこでは,語用論は,音声学,音韻論,形態論,統語論,意味論と同等の資格で言語能力を構成する1部門であると狭い意味に解される.この語用論の見方に基づいた歴史語用論の下位分類として,Brinton のものを挙げよう.ここでは,歴史語用論は,言語学的な色彩が強い.

(1) historical discourse analysis proper

(2) diachronically oriented discourse analysis

(3) discourse oriented historical linguistics

(1) は,過去のある時代における共時的な談話分析で,Jacobs and Jucker の pragmaphilology に近似する.(2) は,談話の経時的変化を観察する通時談話分析である.(3) は,談話という観点から意味変化や統語変化などの言語変化を説明しようとする立場である.

上に述べてきたように,歴史語用論にも種々のレベルでスタンスの違いはあるが,全体としては統一感をもった学問分野として成長してきているようだ.逆にいえば,歴史語用論は学際的な色彩が強く,多かれ少なかれ他領域との連携が前提とされている分野ともいえる.特に European Continental view によれば,歴史語用論は伝統的な文献学とも親和性が高く,従来蓄積されてきた知見を生かしながら発展していくことができる点で魅力がある.

しかし,発展途上の分野であるだけに,課題も少なくない.Jucker (18) は,いくつかを指摘している.

・ 学問分野としてまだ若く,従来の分野の方法論と競合するレベルに至っていない

・ 欧米の主要言語や日本語を除けば,他の言語への応用がひろがっていない

・ 研究の基礎となる,ある言語の歴史的な speech_act の一覧や discourse types/genres の一覧などがまだ準備されていない

・ 研究の基礎となる,"the larger communicative situation of earlier periods" が依然として不明であることが多い

歴史語用論は,有望ではあるが,まだ緒に就いたばかりの分野である.

語用論に関する European Continental view と Anglo-American view の対立については,「#377. 英語史で話題となりうる分野」 ([2010-05-09-1]),「#378. 語用論は言語理論の基本構成部門か否か」 ([2010-05-10-1]) も参照.

・ Jucker, Andreas H. "Historical Pragmatics." Variation and Change. Ed. Mirjam Fried et al. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2010. 110--22.

・ Huang, Yan. Pragmatics. Oxford: OUP, 2007.

2014-09-29 Mon

■ #1981. 間主観化 [subjectification][intersubjectification][semantic_change][unidirectionality][face][t/v_distinction][terminology][discourse_marker][onomasiology]

今日は,昨日の記事「#1980. 主観化」 ([2014-09-28-1]) を発展させた話題として間主観化 (intersubjectification) について取り上げる.Traugott は,"nonsubjective > subjective" という意味変化の延長線上に "subjective > intersubjective" というもう1つの段階があり得ることを提案している.まず,間主観化 (intersubjectification) の行き着く先である間主観性 (intersubjectivity) について,Traugott (128) の説明をみてみよう.

[I]ntersubjectivity is the explicit expression of the SP/W's attention to the 'self' of addressee/reader in both an epistemic sense (paying attention to their presumed attitudes to the content of what is said), and in a more social sense (paying attention to their 'face' or 'image needs' associated with social stance and identity). (128)

そして,間主観化 (intersubjectification) とは,"the development of meanings that encode speaker/writers' attention to the cognitive stances and social identities of addressees" (124) と説明される.

英語から間主観的な表現の例を挙げよう.Actually, I will drive you to the dentist. の "Actually" が間主観的な役割を果たしているという.この "Actually" は,「あなたはこの提案を断るかもしれないことを承知であえて言いますが」ほどの意味を含んでおり,聞き手の face に対してある種の配慮を表わす話し手の態度を表わしている.また,かつての英語における2人称代名詞 you と thou の使い分け (cf. t/v_distinction) も,典型的な間主観的表現である.

間主観化を示す例を挙げると,Let's take our pills now, Roger. における let's がある.本来 let's は,let us (allow us) という命令文からの発達であり,let's へ短縮しながら "I propose" ほどの奨励・勧告の意を表わすようになった.これが,さらに親が子になだめるように動作を促す "care-giver register" での用法へと発展したのである.奨励・勧告の発達は主観化とみてよいだろうが,その次の発展段階は,話し手(親)の聞き手(子)への「なだめて促す」思いやりの態度をコード化しているという点で間主観化ととらえることができる.命令文に先行する please や pray などの用法の発達も,同様に間主観化の例とみることができる.さらに,「まあ,そういうことであれば同意します」ほどを意味する談話標識 well の発達ももう1つの例とみてよい.

聞き手の face を重んじる話し手の態度を埋め込むのが間主観性あるいは間主観化だとすれば,英語というよりはむしろ日本語の出番だろう.実際,間主観性や間主観化の研究では,日本語は引っ張りだこである.各種の敬譲表現に始まり,終助詞,談話標識としての「さて」など,多くの表現に間主観性がみられる.Traugott の "nonsubjective > subjective > intersubjective" という変化の方向性を仮定するのであれば,日本語は,そのどん詰まりにまで行き切った表現が数多く存在する,比較的珍しい言語ということになる.では,どん詰まりにまで行き切った表現のその後はどうなるのか.次の発展段階がないということになれば,どん詰まりには次々と表現が蓄積されることになりそうだが,一方で廃用となっていく表現も多いだろう.Traugott (136) は,次のように想像している.

. . . by hypothesis, intersubjectification is a semasiological end-point for a particular form-meaning pair; onomasiologically, however, an intersubjective category will over time come to have more or fewer members, depending on cultural preference, register, etc.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "From Subjectification to Intersubjectification." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 124--39.

2014-09-12 Fri

■ #1964. プロトタイプ [prototype][phonology][phoneme][phonetics][syllable][prosody][terminology][semantic_change][family_resemblance][philosophy_of_language][onomasiology]

認知言語学では,プロトタイプ (prototype) の考え方が重視される.アリストテレス的なデジタルなカテゴリー観に疑問を呈した Wittgenstein (1889--1951) が,ファジーでアナログな家族的類似 (family resemblance) に基づいたカテゴリー観を示したのを1つの源流として,プロトタイプは認知言語学において重要なキーワードとして発展してきた.プロトタイプ理論によると,カテゴリーは素性 (feature) の有無の組み合わせによって表現されるものではなく,特性 (attribute) の程度の組み合わせによって表現されるものである.程度問題であるから,そのカテゴリーの中心に位置づけられるような最もふさわしい典型的な成員もあれば,周辺に位置づけられるあまり典型的でない成員もあると考える.例えば,「鳥」というカテゴリーにおいて,スズメやツバメは中心的(プロトタイプ的)な成員とみなせるが,ペンギンやダチョウは周辺的(非プロトタイプ的)な成員である.コウモリは科学的知識により哺乳動物と知られており,古典的なカテゴリー観によれば「鳥」ではないとされるが,プロトタイプ理論のカテゴリー観によれば,限りなく周辺的な「鳥」であるとみなすこともできる.このように,「○○らしさ」の程度が100%から0%までの連続体をなしており,どこからが○○であり,どこからが○○でないかの明確な線引きはできないとみる.

考えてみれば,人間は日常的に事物をプロトタイプの観点からみている.赤でもなく黄色でもない色を目にしてどちらかと悩むのは,プロトタイプ的な赤と黄色を知っており,いずれからも遠い周辺的な色だからだ.逆に,赤いモノを挙げなさいと言われれば,日本語母語話者であれば,典型的に郵便ポスト,リンゴ,トマト,血などの答えが返される.同様に,「#1962. 概念階層」 ([2014-09-10-1]) で話題にした FURNITURE, FRUIT, VEHICLE, WEAPON, VEGETABLE, TOOL, BIRD, SPORT, TOY, CLOTHING それぞれの典型的な成員を挙げなさいといわれると,多くの英語話者の答えがおよそ一致する.

英語の FURNITURE での実験例をみてみよう.E. Rosch は,約200人のアメリカ人学生に,60個の家具の名前を与え,それぞれがどのくらい「家具らしい」かを1から7までの7段階評価(1が最も家具らしい)で示させた.それを集計すると,家具の典型性の感覚が驚くほど共有されていることが明らかになった.Rosch ("Cognitive Representations of Semantic Categories." Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 104 (1975): 192--233. p. 229) の調査報告を要約した Taylor (46) の表を再現しよう.

| Member | Rank | Specific score |

|---|---|---|

| chair | 1.5 | 1.04 |

| sofa | 1.5 | 1.04 |

| couch | 3.5 | 1.10 |

| table | 3.5 | 1.10 |

| easy chair | 5 | 1.33 |

| dresser | 6.5 | 1.37 |

| rocking chair | 6.5 | 1.37 |

| coffee table | 8 | 1.38 |

| rocker | 9 | 1.42 |

| love seat | 10 | 1.44 |

| chest of drawers | 11 | 1.48 |

| desk | 12 | 1.54 |

| bed | 13 | 1.58 |

| bureau | 14 | 1.59 |

| davenport | 15.5 | 1.61 |

| end table | 15.5 | 1.61 |

| divan | 17 | 1.70 |

| night table | 18 | 1.83 |

| chest | 19 | 1.98 |

| cedar chest | 20 | 2.11 |

| vanity | 21 | 2.13 |

| bookcase | 22 | 2.15 |

| lounge | 23 | 2.17 |

| chaise longue | 24 | 2.26 |

| ottoman | 25 | 2.43 |

| footstool | 26 | 2.45 |

| cabinet | 27 | 2.49 |

| china closet | 28 | 2.59 |

| bench | 29 | 2.77 |

| buffet | 30 | 2.89 |

| lamp | 31 | 2.94 |

| stool | 32 | 3.13 |

| hassock | 33 | 3.43 |

| drawers | 34 | 3.63 |

| piano | 35 | 3.64 |

| cushion | 36 | 3.70 |

| magazine rack | 37 | 4.14 |

| hi-fi | 38 | 4.25 |

| cupboard | 39 | 4.27 |

| stereo | 40 | 4.32 |

| mirror | 41 | 4.39 |

| television | 42 | 4.41 |

| bar | 43 | 4.46 |

| shelf | 44 | 4.52 |

| rug | 45 | 5.00 |

| pillow | 46 | 5.03 |

| wastebasket | 47 | 5.34 |

| radio | 48 | 5.37 |

| sewing machine | 49 | 5.39 |

| stove | 50 | 5.40 |

| counter | 51 | 5.44 |

| clock | 52 | 5.48 |

| drapes | 53 | 5.67 |

| refrigerator | 54 | 5.70 |

| picture | 55 | 5.75 |

| closet | 56 | 5.95 |

| vase | 57 | 6.23 |

| ashtray | 58 | 6.35 |

| fan | 59 | 6.49 |

| telephone | 60 | 6.68 |

プロトタイプ理論は,言語変化の記述や説明にも効果を発揮する.例えば,ある種の語の意味変化は,かつて周辺的だった語義が今や中心的な語義として用いられるようになったものとして説明できる.この場合,語の意味のプロトタイプがAからBへ移ったと表現できるだろう.構文や音韻など他部門の変化についても同様にプロトタイプの観点から迫ることができる.

また,プロトタイプは「#1961. 基本レベル範疇」 ([2014-09-09-1]) と補完的な関係にあることも指摘しておこう.プロトタイプは,ある語が与えられたとき,対応する典型的な意味や指示対象を思い浮かべることのできる能力や作用に関係する.一方,基本レベル範疇は,ある意味や指示対象が与えられたとき,対応する典型的な語を思い浮かべることのできる能力や作用に関係する.前者は semasiological,後者は onomasiological な視点である.

・ Taylor, John R. Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

2012-08-30 Thu

■ #1221. 季節語の歴史 [semantic_change][lexicology][metonymy][calendar][onomasiology]

Fischer が英語の季節語に関する興味深い論文を書いている.要約すると次のようになる.

ゲルマン文化において,1年は夏と冬の2季に区分されていた.しかし,四季を区分する南欧文化との接触により,早くから春と秋の概念も入ってきてはいた.古英語では,sumer と winter の伝統的な2季区分に加えて,狭義に春の特定の1期間を表わす lencten が 広義に「春」として用いられ,狭義に秋の特定の1期間を表わす hærfest が広義に「秋」として用いられる例があり,現代のように四季の概念も語も揃っていた.ただし,lencten と hærfest のそれぞれの語には相変わらず狭義も併存していたため,専ら広義に季節を表わす現代英語の spring や autumn, fall と比べると,季節名称としての存在感はやや希薄だった.

中英語になると,古英語 lencten に対応する語は狭義へと退行する.14--15世紀には広義の「春」を失い,「春」の意味の場を巡る語彙の競合が始まる.「春」の意味の場は不安定となり,かつてのゲルマン的2季区分の記憶ゆえか,sumer が「春」をも含む超広義を発達させる.こうして,13世紀後半には,春の到来を告げる表現 Sumer is icumen in が現われた.

近代英語に入ると,「春」を巡る競合を制して,spring が台頭してくる.これは,植物が芽吹くイメージに重ね合わせた比喩として,生き生きとした表現に感じられたためかもしれない.spring of the leaf のような metonymy 表現もあれば,spring of the year のような metaphor もあった.同様に,古英語以降長らく「秋」を担当していた hervest も,18世紀の終わりまでには,やはり植物に比喩を取った fall や,フランス借用語の autumn などの類義語に徐々に地位を明け渡した.最終的に,同じように植物に比喩をとった spring と fall が生き残ったのは偶然ではないだろう.

Fischer は,以上の結論を得るために,古英語から近代英語にかけての「春」「秋」語彙を詳細に調査し,季節語の多義の消長を示す semasiological diagram と,季節に対応する類義語の消長を示す onomasiological diagram を描いた.結論の一環として,spring の存在は drag-chain によって,harvest の消失は push-chain によって説明されるとしている点も興味深い (86) .

・ Fischer, Andreas. "'Sumer is icumen in': The Seasons of the Year in Middle English and Early Modern English". Studies in Early Modern English. Ed. Dieter Kastovsky. Mouton de Gruyter, 1994. 79--95.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow