2026-01-19 Mon

■ #6111. Morris の Austral English の序文より [australian_english][dictionary][lexicography][lexicology][oed][melbourne][new_zealand_english]

昨日の記事「#6110. Edward Ellis Morris --- オーストラリア英語辞書の父」 ([2026-01-18-1]) に引き続き,Morris と彼が編纂した辞書 Austral English (1898年刊行)について.この辞書の序文に当たる "ORIGIN OF THE WORK" というセクションに,後に完成する OED との関係が明記されている.

. . . the noblest monument of English scholarship is The New English Dictionary on Historical Principles, founded mainly on the materials collected by the Philological Society, edited by Dr. James Murray, and published at the cost of the University of Oxford. The name New will, however, be unsuitable long before the Dictionary is out of date. Its right name is the Oxford English Dictionary ('O.E.D.'). That great dictionary is built up out of quotations specially gathered for it from English books of all kinds and all periods; and Dr. Murray several years ago invited assistance from this end of the world for words and uses of words peculiar to Australasia, or to parts of it. In answer to his call I began to collect; but instances of words must be noted as one comes across them, and of course they do not occur in alphabetical order. The work took time, and when my parcel of quotations had grown into a considerable heap, it occurred to me that the collection, if a little further trouble were expended upon it, might first enjoy an independent existence. Various friends kindly contributed more quotations: and this Book is the result.

このような事情で,このオーストラリア・ニュージーランド英語の辞書は OED と連動して生み出された点でユニークである.以下,Kel (92--100) の記述を参考に,Austral English をめぐる注目すべき事柄をいくつか示そう.

・ Morris が主に収集したのは (1) 既存の英単語だが意味・用法が異なる "altered words",そして (2) アボリジニー諸言語からの借用語である.

・ オーストラリアのイギリス植民地としての歴史は当時まだ120年ほどの短いものだったが,それでも約2000の見出し語を含む500ページに及ぶ辞書が編纂されたというのは,対蹠地における造語の豊かさ物語っている.

・ 編纂方法が OED と同じ「歴史的原則」に基づいていたというのも辞書編纂史上,特筆すべき出来事である.OED の完成は Austral English の30年後の1928年だったことを考えると,ある意味では,歴史的原則に基づいた学術的な英語辞書の一番乗りだったともいえる.

・ kangaroo の項目は7ページに及ぶ.

・ この辞書には批判もあった.Morris は本質的にイギリス出身のエリート学者であり,オーストラリア英語を最も顕著に特徴づける話し言葉や俗語には注意を払っていない,という批判だ.Morris の選語は書き言葉に偏っており,網羅性に欠けていた,と.確かにその通りだが,それは OED とておおよそ同じ状況だったことは考え合わせておいてよいだろう.

・ Morris, Edward Ellis, ed. Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages. London: Macmillan, 1898.

・ Richards, Kel. The Story of Australian English. Sydney: U of New South Wales, 2015.

2026-01-18 Sun

■ #6110. Edward Ellis Morris --- オーストラリア英語辞書の父 [australian_english][dictionary][lexicography][lexicology][oed][link][biography][melbourne][new_zealand_english]

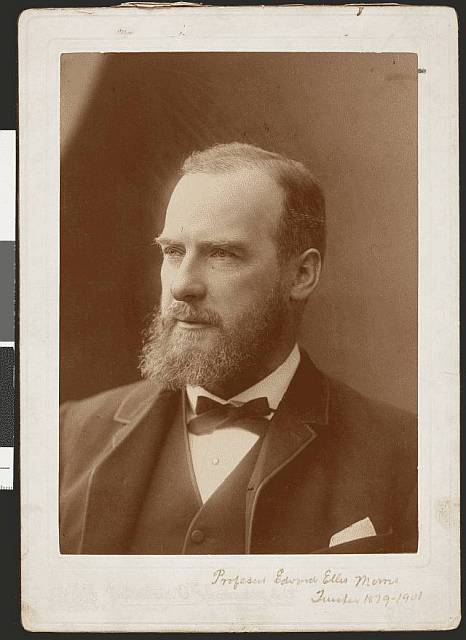

(Photograph of Edward Morris, by Johnstone, O'Shannessy & Co, c1900, State Library of Victoria, H4705)

オーストラリアの Melbourne と英語史を掛け合わせると,Edward Ellis Morris (1843--1902) の名前が浮かび上がってくる.1898年に Austral English: A dictionary of Australasian words, phrases and usages with those aboriginal-Australian and Maori words which have become incorporated in the language, and the commoner scientific words that have had their origin in Australasia と題するオーストラリア英語・ニュージーランド英語の語彙を集め,初めて本格的に辞書を編纂した人物である.

当時 Oxford にて New English Dictionary (後の Oxford English Dictionary)を編纂していた James Murray (1837--1915) は,世界中の有志に呼びかけ,英単語の引用文例を収集していた.オーストラリア英語からの素材を提供していた有志こそが,メルボルン大学の現代語・文学の教授 Morris その人だった.後にその素材を独立させて辞書として編んだのが,Austral English である.

Morris は,1843年,英領インドで会計課長を務めていた父のもと Madras で生まれた.教育はイギリスで受け,ラグビー学校やオックスフォード大学でエリートとして育ち,古典,法律,近代史を学び,フランス語やドイツ語を習得した.1875年,メルボルン英国教会グラマースクールの校長に任命されてオーストラリアに渡り,生涯をその地で過ごした.1884年にはメルボルン大学の教授として招かれ,現代語・文学で教鞭を執った.1902年,滞在中のイングランドで他界し,ロンドンの Kensal Green Cemetery に眠っている.

Morris は敬虔なクリスチャン,慈善家,教育家だった.1884--88年には Melbourne Shakespeare Society を創設し初代会長となっている.このように多分野で活動した Morris の多くの著作のうち最も著名なものが,オーストラリア英語研究の記念碑というべき Austral English である.Morris はこの著作により,1899年に同大学最初の文学博士号を授与されている.現代まで続くオーストラリア英語辞書の系譜の祖といってよい.

・ Biography by Australian Dictionary of Biography

・ Biography by Dictionary of Australian Biography

・ Biography by People Australia

・ Wikipedia

・ Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages by Project Gutenberg

・ Morris, Edward Ellis, ed. Austral English: A Dictionary of Australasian Words, Phrases and Usages. London: Macmillan, 1898.

2025-11-20 Thu

■ #6051. NZE の起源をめぐる4つの説 [new_zealand_english][australian_english][cockney][dialect_contact][dialect_mixture][koineisation]

連日参照している Bauer に,ニュージーランド英語の起源をめぐる4つの学説が紹介されている (420--28) .いずれもオーストラリア英語を横目に睨みながら,比較対照しながら提唱されてきた説である.なお,両変種を指す便宜的な用語として Australasian が用いられていることに注意.

1. Australasian as Cockney

オーストラリア英語は18世紀のロンドン英語(Cockney の前身)にルーツがあるのと同様に,ニュージーランド英語は19世紀のロンドン英語にルーツがある.両変種に差異がみられるとすれば,それは18世紀と19世紀のロンドン英語の差異に起因する.(しかし,ニュージーランド移民は Cockney ではなく,むしろ Cockney を軽蔑していたとも考えられており,この説の信憑性は薄いと Bauer は評価している.)

2. Australasian as East Anglian

Trudgill が示唆するところによれば,オーストラリア英語とニュージーランド英語の発音特徴は,ロンドン英語ではなく East Anglian に近いという.ただし,Trudgill は,直接 East Anglian から派生したと考えているわけではなく,ロンドン英語を主要素としつつ,East Anglian を含むイングランド南東部の諸方言英語が混合してできた "a mixed dialect" だという意見だ.(Bauer は,取り立てて East Anglian を前面に出す説に疑問を呈している.他の方言も候補となり得るのではないか.)

3. The mixing bowl theory

オーストラリア英語やニュージーランド英語は,諸方言が合わさってできた方言混合 (dialect_mixture) である,という説.Bauer は,もっともらしい説ではあるが,ランダムな混合だとすれば両変種が非常に類似しているのはなぜか疑問が残ると述べている.一方,Trudgill は koineisation の用語で,両変種の類似性を説明しようとしている.

4. New Zealand English as Australian

ニュージーランド英語は,オーストラリア英語から派生した変種である.きわめて分かりやすい説で,Bauer は "The influence of Australia in all walks of life is ubiquitous in New Zealand" (427) と述べつつ,この説を推している.ただし,ニュージーランド人の感情を考えると慎重にならざるを得ないようで,"it is politically not a very welcome message in New Zealand. I shall thus try to present this material in a suitably tentative manner" (425) とも述べている.それでも,結論部では次のように締めくくっている (428) .

I do not believe that the arguments are cut and dried, but it does seem to me that, in the current state of our knowledge, the hypothesis that New Zealand English is derived from Australian English is the one which explains most about the linguistic situation in New Zealand.

この話題は先日 heldio でも要約して「#1632. ニュージーランド英語はどこから来たのか?」として配信したので,ぜひお聴きいただければ.また,関連して,hellog 「#5974. New Zealand English のメイキング」 ([2025-09-04-1]) と「#1799. New Zealand における英語の歴史」 ([2014-03-31-1]) も要参照.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-11-19 Wed

■ #6050. ニュージーランドはアメリカ英語と距離を置きたい? [new_zealand_english][ame][sociolinguistics][americanisation]

ニュージーランドはオーストラリアとともに歴史的にイギリスとの結びつきが強く,話されている英語変種についても,明らかにイギリス系変種からの派生であり,アメリカ変種と比べると差がある.しかし,世界における米国(の英語)の圧倒的な影響力のもと,ニュージーランド英語もご多分に漏れず,主に語彙などで americanisation の気味がみられる.

ニュージーランド人にとって,英語のアメリカ化は現実としては受け入れざるを得ないところがあるだろうが,心情としてはあまり好ましく思っていない向きもありそうだ.アメリカ英語への嫌悪感や,あるいは逆に憧れは,世代によっても異なるだろう.Bauer は,ニュージーランド人の対アメリカ英語感情について,次のように述べている.

. . . there exists in New Zealand (as in Britain) an anti-American linguistic chauvinism which is entirely surprising in the light of the general use in the community of a number of forms which are American in origin. It is not clear how widespread these attitudes are in the community, but the fact that they exist is shown by the following extracts from Letters to the Editor of New Zealand periodicals:

Most of our worst grammatical or pronunciatory [sic] errors stem from America. (The Listener, 10 November 1973)

Why don't we improve our English instead of adopting a worse speech from a culture which branched off from England several centuries ago? (The Listener, 25 November 1978)

We are not Americans, and I know I for one do not like the way this country is trying to carbon copy itself with American influence. (The Otago Daily Times, 12 September 1984)

Bauer がニュージーランド英語を概説的に記述したのは30年以上も前のことでもあり,現状がどうなっているのか詳しくは分からない.ただし,とりわけ年配の人々が若者のアメリカンな言葉遣いを嘆かわしく思っている,という事情は今でも変わらずあるようである.関連して,heldio 配信回「#1631. アメリカ英語は嫌われ者?」もどうぞ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-11-18 Tue

■ #6049. タスマン海をまたいでアチコチ移動する等語線 [dialectology][dialect][isogloss][new_zealand_english][australian_english][variety][geography][dialect_continuum]

ニュージーランド英語とオーストラリア英語の関係については,通時的に共時的にも様々な議論があり,考察すべき問題が多い.特にニュージーランド英語のほうは,オーストラリア英語にどれほど依存しているのか,あるいはむしろ独立しているのかという論点において,アイデンティティ問題と関わってくるので,議論が熱くなりやすいのだろう.両国の間に横たわるタスマン海 (the Tasman Sea) は,両サイドの英語変種を結びつけている橋のか,あるいは隔てている壁なのか.

この議論と関連して,興味深い事実がある.通常,海や川や山などの自然の障壁は人々の往来を阻みやすいため,そこが言語境界や方言境界となることが多い.とりわけ単語・語法の分布で考えるならば,等語線 (isogloss) が自然の障壁を越えていくことはあまりない,と言ってよい.タスマン海のような地理的に明らかに大きな断絶は,オーストラリア英語とニュージーランド英語を隔てる自然の障壁となるはずだ.

ところが,おもしろいことに,個々の単語・語法によって様相は異なるものの,両変種においては等語線が自然の障壁を越えている例がある.ニュージーランド側から見れば,等語線が国内にはなくタスマン海を西に渡ったオーストラリア側にある,という奇妙な現象が起こっている.

Bauer の挙げている例を見てみよう (413) .

Interestingly enough, some of the isoglosses distinguishing New Zealand English regional dialects cross the Tasman into Australia. Turner . . . comments that the construction boy of O'Brien is also found in Newcastle, New South Wales. Crib is also found meaning 'lunch' in Australia. Small red-skinned sausages are called cheerios in New Zealand, as they are in Queensland, but not elsewhere in Australia . . . . Polony, mentioned above as an Auckland word, is also found in Western Australia . . . . Slater, which is a widespread New Zealand English word, though originally from the South Island, is also found in New South Wales . . . . Blood nose 'nose bleed' is normal in New Zealand, but restricted to Victoria and South Australia in Australia . . . . New Zealand can thus be seen as part of a larger Australasian dialect area in more ways than just sharing vocabulary with Australia.

ちなみに引用内にある polony は「香辛料をたっぷりきかせた豚肉の燻製ソーセージ」,slater は「フナムシ,ワラジムシ」を意味する.食物や動物などの日常語は一般に方言差が出やすく,その点で上記の例も方言学の一般的な傾向を示しているといえるだけに,等語線が海を飛び越えている様が興味深い.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-11-15 Sat

■ #6046. オタゴ大学 --- ダニーデンにあるニュージーランド最古の大学 [university_of_otago][new_zealand_english][sociolinguistics][history]

一昨日の heldio 配信「#1628. ニュージーランド最古のオタゴ大学の時計台の前より」は,NZの南島のダニーデンに位置するオタゴ大学(University of Otago)のキャンパスからお届けしました.大学のシンボルである時計台の前に広がる芝生より,この地の植民史と英語史に思いを馳せました.

Captain Cook (1728--79) が1769年にニュージーランドに訪れ,先住民のマオリ人と初めて接触した後,この地はヨーロッパ人たちにとって鯨やアザラシの漁場となりました.その後,1840年に正式にイギリスの植民地となり,主にイギリス人による植民が一気に進みました.その後間もない1869年には,ダニーデンにニュージーランド最古の大学としてオタゴ大学が創立されました.このスピーディな展開には驚くばかりです.背後には初期移民たちの宗教上の情熱,啓蒙思想,勤勉さがあったのですが,その程度がいかに凄まじかったかが想像されます.

オタゴ大学の創立,より広くはダニーデンという町の建設に関わった初期移民の顔ぶれを見ると,スコットランド一色であることがわかります.初代学長を務めたのは,熱心な聖職者であった Thomas Burns (1796--1871) です.彼は,スコットランドを代表する詩人 Robert Burns (1759--96) の甥にあたります.

また,私が愛着を感じてやまないのは,このオタゴ大学の時計台が,私の母校でもあるスコットランドのグラスゴー大学の建築様式にインスピレーションを受けているという事実です.ダニーデンの町並み全体が,スコットランドの首都エディンバラを思わせる一方で,この大学の時計台はグラスゴーの雰囲気を纏っているのです!

この大学の歴史を語る上でもう1つ見逃せないのが,女性の入学を許可したことです.1871年の新体制において,オタゴ大学は,イギリス帝国内で初めてすべての階層の女性に学びの扉を開いた大学となりました.

もう1点,同時代の大きな出来事として,この町の急速な経済発展を支えた1861年のゴールドラッシュがあります.これにより,オーストラリア人をはじめとして,遠く中国からも多くの人々が金に惹かれて流入しました.これは,スコットランド英語の影響が強かった,この土地の初期の英語に,オーストラリア英語や,さらに異言語との接触の機会を与えることになりました.ニュージーランド英語史上の重要な契機だったといってよいでしょう.

ダニーデンという都市とオタゴ大学は,英語史のメインストリームからは外れたニュージーランドという場所にありながらも,英語の拡散,変種の移植,方言・言語接触といった,英語史における社会言語学的な話題を凝縮して見せてくれています.

2025-11-13 Thu

■ #6044. 地域変種の差異がレジスターの差異に転嫁されるケース --- NZE の語彙より [new_zealand_english][vocabulary][register][lexical_stratification][ame_bre][synonym][variety]

New Zealand English を概説している Bauer が,北米英語の NZE への影響について考察している箇所で,同一指示対象に対して英米系語彙を使い分けている興味深い慣行に触れている (419) .

One interesting use of American vocabulary in New Zealand English is to provide high-style advertising terms. Given a pair such as torch and flashlight, the British version is the one most likely to be used in everyday speech, and the American one is likely to be used commercially, to make the product sound more appealing. Thus one would normally pull the curtains, but the shop might sell you drapes. Other pairs with a similar relationship are lift/elevator, nappy/diaper and possibly (although there may be a semantic distinction here) biscuit/cookie. Bayard (1989) comments on such pairs in some detail, pointing out that for younger speakers, the American member of such pairs, even if it is not widely used, is considered to be 'better' English (a term Bayard deliberately does not define more closely).

本来は英語の英米差という地域変種間の差異に基づくペア語彙が,NZE ではレジスター差を表わすために利用されている事例だ.より正確にいえば,日常用と商用というフィールドの差に利用されているといえるだろうか.

また,その際にどちらのオリジナル変種が日常用に対応しており,どちらが商用に対応しているのかもおもしろい問題だ.事実としては,イギリス系が日常用で,アメリカ系が商用となっているようだが,これはまた納得感がある.NZE の基本はイギリス系だが,商業が絡むとアメリカ系が入ってくる,というわけだ.

もしかすると,これは NZE に限らない現象かもしれない.variety の register 化,あるいは user variety の use variety 化などと呼べる興味深い現象だ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-11-08 Sat

■ #6039. New Zealand English におけるマオリ借用語の発音をめぐる社会言語学 [sociolinguistics][new_zealand_english][maori][borrowing][loan_word][pronunciation][orthography][language_planning][writing][standardisation]

NZE には,マオリ語からの借用語が多く入っている.地名や人名などの固有名詞はもちろん,一般語も多く流入している.英語の文脈でマオリ借用語をどのように発音するか,という問題について,Bauer (398--99) が興味深い論点を示している.

The proper pronunciation of Maori is currently a controversial issue in New Zealand, and it is a subject on which feelings run high. The issue is at heart a political rather than a linguistic one, since it is clear linguistically that there is no good reason to expect native-like Maori pronunciation in words which are being used in English. None the less, it has the linguistic consequence that there is a good deal of variation in the way in which Maori loanwords are pronounced in English, with variants close to native Maori norms at the formal end of the spectrum, and much more Anglicised versions --- sometimes irregularly Anglicised versions --- at the other. To give some idea of the variation this can lead to, I present below a few place-names with a Maori pronunciation and one extreme English pronunciation. Variants are heard anywhere on the continuum between these two extremes.

この文章の後に具体例がいくつか挙げられているが,たとえばマオリ語でニュージーランドを表わす Aotearoa (長く白い雲の土地)は,マオリ語母語発音では /aːɔtɛːaɾɔa/ となり,これで発音する英語話者もいれば,そこから完全に英語化した /eɪətiəˈɹəʊə/ として発音する者もいる.また,この2つを両極として,中間的な発音も多数あり得るというのだから,揺れの激しさが想像される.

この揺れの背景には,英語とマオリ語の音韻体系の差異,マオリ語のリテラシー,オーディエンスへの配慮,マオリ語への立ち位置や思い入れ,言語計画・政策上の立場など,様々な言語学的,そしてなかんずく社会言語学的な要因が作用しているのだろう.国号の発音を1つとっても,そこに話者の態度や立場が色濃く反映している可能性があるということだ.

なお,マオリ語をローマ字で表記する際の綴字は,1830年代後半から1840年代までには標準化されていたという (Bauer 398) .意外と早かったのだな,という印象だ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2025-11-07 Fri

■ #6038. New Zealand English における2音節発音の known, thrown, grown [new_zealand_english][vowel][syllable][pronunciation][sound_change][oe]

昨日の記事「#6307. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形」 ([2025-11-06-1]) に続き,New Zealand English で聞かれる特徴ある発音について取り上げる.Bauer (391) に次のように記述がある.

There is a small set of words such as known, thrown, which are regularly pronounced with two syllables, allowing distinctions between such pairs as groan/grown.

LPD に当たってみると,それぞれ標準的な単音節発音の次に,§/ˈnəʊ ən/, §/ˈθrəʊ ən/, §/ˈgrəʊ ən/ と2音節発音も掲載されている,LPD における § 記号については,"Pronunciations which are widespread among educated speakers of British English but which are not, however, considered to belong to RP (Received Pronunciation) are marked with the symbol §." (xix) とあるので,イギリス英語でも非RP発音としては広く聞かれるもののようだ.

この2音節発音に思わず唸ってしまうのは,これがおそらく古英語以来の歴史的発音を由緒正しく引き継いでいるからだ.古英語では上記の動詞はいずれも強変化第7類に属し,過去分詞はそれぞれ knāwen, þrōwen, grōwen となる.MED で中英語の語形を確かめると,2音節目の母音を示唆する母音字が残っているものもあれば,残っていないものもある.少なくとも中英語期以降,単音節発音と2音節発音は variants としていずれも行なわれてきたことが分かる.

古英語から1千年の時間が流れ,かつ地中の裏側の対蹠地で話されている現代 NZE において,特徴的に2音節発音が残っているというのは感慨深い.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-11-06 Thu

■ #6037. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形 [new_zealand_english][article][glottal_stop][consonant][vowel][phonetics][allomorph][phonetics][pronunciation]

冠詞 (article) (定冠詞と不定冠詞)の実現形は,英語の変種によっても,話者個人によっても,状況によっても様々である.典型的な機能語として強形と弱形の variants をもっているという事情もあり,状況はますます複雑となる(cf. 「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1])).さらに,後続語が子音で始まるか母音で始まるかによっても変異するので,厄介だ.

とりわけ定冠詞の実現形については,過去記事「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]),「#2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考」 ([2015-06-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

さて,地域変種によっても実現形はまちまちのようだが,New Zealand English の状況を見てみよう.Bauer (391) によると,後続音によらず定冠詞は /ðə/ ,不定冠詞は /ə/ と発音される傾向があるという.ただし,母音が後続する場合にはたいてい声門閉鎖音がつなぎとして挿入される.

As in South African English . . . , the and a do not always have the same range of allomorphs in New Zealand English that they have in standard English. Rather, they are realised as /ðə/ and /ə/ independent of the following sound. Where the following sound is a vowel, a [ʔ] is usually inserted.

目下ニュージーランド滞在中で NZE を耳にしているが,そもそも冠詞は弱く発音されることが多く,どの変種でも variants が多々あることを前提としてもっていたので,さほどマークしていなかった.今後は意識して聞き耳を立てていきたい.

別途 LPD で the を引いてみると,次のようにある.

the strong form ðiː, weak forms ði, ðə --- The English as a foreign language learner is advised to use ðə before a consonant sound (the boy, the house), ði before a vowel sound (the egg, the hour). Native speakers, however, sometimes ignore this distribution, in particular by using ðə before a vowel (which in turn is usually reinforced by a preceding [ʔ]), or by using ðiː in any environment, though especially before a hesitation pause. Furthermore, some speakers use stressed ðə as a strong form, rather than the usual ðiː.

NZE に限らず,他の変種においても実現形は多様と考えてよいだろう.また,つなぎの声門閉鎖音の挿入も,ある程度一般的といってよさそうだ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-09-08 Mon

■ #5978. ONZE --- Origins of New Zealand English Project [link][new_zealand_english][variety][language_change][bibliography]

ニュージーランド英語 (new_zealand_english) の起源を探る調査が1980年代後半から活発化してきている.その中心的な役割を果たしてきたのが ONZE (Origins of New Zealand English Project) というプロジェクトだ.ニュージーランドのカンタベリ大学が拠点となっている.

Williams (1998--99) による簡単な紹介を読んでみよう.

For the origins of the New Zealand accent, a unique set of data are available in the form of recordings made throughout rural New Zealand in the 1940s, among them some of the first New-Zealand-born speakers of English which allowed people on the Origins of New Zealand English Project (ONZE n.d.) to document the embryonic stages of the New Zealand accent.

ONZE の調査とその成果については,Gordon (et al.) や Trudgill の一連の研究が詳しい.以下に主要な論著の書誌を挙げておく.

・ Gordon, Elizabeth. "That Colonial Twang: New Zealand Speech and New Zealand Identity." Culture and Identity in New Zealand. Ed. David Novitz and Bill Willmott. Wellington: GP Books, 1989. 77--90.

・ Gordon, Elizabeth. "The Origins of New Zealand Speech: The Limits of Recovering Historical Information from Written Records." English World-Wide 19(19): 61--85.

・ Gordon, Elizabeth and Andrea Sudbury. "The History of Southern Hemisphere Englishes." Alternative Histories of English. Ed. Richard Watts and Peter Trudgill. London: Routledge, 2002. 67--86.

・ Gordon, Elizabeth, Lyle Campbell, Jennifer Hay, Margaret MacLagan, Andrea Sudbury, and Peter Trudgill. New Zealand English: Its Origins and Evolution. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge UP, 2004.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Dialects in Contact. Oxford: Blackwell, 1986.

・ Trudgill, Peter. "A Window on the Past: 'Colonial Lag' and New Zealand Evidence for the Phonology of Nineteenth-Century English." American Speech 74(3): 227--39.

・ Trudgill, Peter. New Dialect Formation: The Inevitability of Colonial Englishes. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2004.

・ Trudgill, Peter, Elizabeth Gordon, Gillian Lewis, and Margaret Maclagan. "Determinism in New-Dialect Formation and the Genesis of New Zealand English." Journal of Linguistics 36: 299--318.

・ Williams, Colin H. "Varieties of English: Australian/New Zealand English." Chapter 127 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1995--2012.

2025-09-06 Sat

■ #5976. オーストラリア英語とニュージーランド英語は「つかず離れず」 [new_zealand_english][australian_english][variety][world_englishes][history_of_linguistics]

イギリスからみて地球の裏側にあることから「対蹠地」 (the Antipodes) と称されるオーストラリアとニュージーランド.この2つの地域で行なわれている英語変種は,それぞれオーストラリア英語 (Australian English; AusE),ニュージーランド英語 (New Zealand English; NZE) といわれる.

歴史的,地理的,文化的に近い変種なので,しばしば一緒に扱われる.一般的には国としての「大きさ」の違いが念頭にあるからか,AusE がメインで NZE がサブと扱われることが多い.もちろん,このような認識は NZE 話者にとっては快いものではないだろう.

両変種の研究史をみても,AusE のほうが手厚く扱われてきたという事情はある.しかし,ここ30年ほどの間に事情が変わってきた.NZE は AusE と比べて,いな他の主要な英語変種と比べても,さかんに研究されるようになってきたのである.両変種を同じ章のなかで概説している Williams の冒頭の段落を引用する (1996) .

The concept of a joint chapter on Australian (AusE) and New Zealand English (NZE) is controversial, especially to New Zealanders who might justly object to being treated simply as an appendix to Australia. Initially, the description of NZE lagged behind that of the variety across the Tasman: in the early 1990s, there was a more substantial body of research on AusE; the situation has been rectified, however, and NZE is no longer "the dark horse of World English regional dialectology" (Crystal 1995: 354) but one of the most researched varieties worldwide . . . . In fact, as far as the evolution of the regional accent is concerned, much better evidence is available for NZE . . . . The history of the two varieties receives separate treatment in volume 5 of the Cambridge History of the English Language (Burchfield 1994). The histories of Australia and New Zealand are closely connected, however . . . , and the following account will not treat the development of the two varieties separately. Instead, the historical account of their accents, lexicon, grammar, and dialects will take a comparative approach in order to tease out the common ground and differences in the development of the two inner-circle varieties in the south Pacific.

先日の記事「#5974. New Zealand English のメイキング」 ([2025-09-04-1]) で触れたように,AusE と NZE の関係は複雑である.深い関係にあることは確からしいが,何がどこまで互いの影響によるものなのか具体的につかめないことが多いからだ.今後の本ブログでも,両変種の「つかず離れず」を味わっていこうと思う.

・ Williams, Colin H. "Varieties of English: Australian/New Zealand English." Chapter 127 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1995--2012.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1995.

2025-09-04 Thu

■ #5974. New Zealand English のメイキング [new_zealand_english][maori][history][cockney][sociolinguistics][variety][founder_principle][dialect_contact][dialect_mixture][dialect_levelling][australian_english][100_places]

ニュージーランド英語については「#1799. New Zealand における英語の歴史」 ([2014-03-31-1]),「#402. Southern Hemisphere Shift」 ([2010-06-03-1]),「#278. ニュージーランドにおけるマオリ語の活性化」 ([2010-01-30-1]) を含む new_zealand_english の記事群で取り上げてきた.今回は最近お気に入りの A History of the English Language in 100 Places の第52節 "WAITANGI --- the English Language in New Zealand (1840)" より,New Zealand English のメイキングについての解説を読みたい (129--31) .

On 6 February 1840, at Waitangi, Aoteoroa, Maori chiefs signed a treaty with the representatives of the British government. The Maori were agreeing to permanent white settlement in their islands. The treaty of Waitangi signalled the moment when the British, not the French, asserted possession of what was renamed New Zealand; it was also the moment when English was destined to become the dominant European language of Aotearoa.

After 1840, European migration to New Zealand came almost exclusively from the British Isles. A census in 1871 showed that of these various migrants, 51 per cent came from England, 27 per cent from Scotland, 22 per cent from Ireland. The majority spoke regional dialects unlike the upper-class English of the colony's administrators. That division shaped linguistic attitudes and accents until the 1960s at least. At the same time, the Maori language provided many terms for local animals, plants and landscape features.

The proportions of the 1871 census suggest the founding elements of New Zealand English, but they do not take account of the fact that there was a continuous movement back and forth between New Zealand and Australia. Some 6 per cent of the 1871 white population was born in Australia, and very large numbers of those who came from the British Isles first landed in Australia before deciding to move to New Zealand. Australian English had then --- and continues to have --- a strong influence. . . .

As in Australia, school inspectors, administrators and leaders of opinion complained from the beginning about the kind of English that they found widespread in New Zealand. A major complaint was that many New Zealanders said 'in', not 'ing', a the ends of words; they added and dropped 'h's improperly; and generally sounded Cockney.

New Zealand linguists challenged the idea that there were large numbers of Londoners among the immigrants to New Zealand. Moreover, within England and the Empire, Cockney was the accent most disliked by upper-class English speakers, and there was a tendency to label any disliked accent as Cockney. Arguing for a levelling of the nineteenth-century English, Irish and Scottish immigrant dialects, New Zealand linguists claim that a distinctive voice appeared about 1900 and spread rapidly through the country. It was initially noted in derogatory terms as a colonial drawl or twang. However, modern-day New Zealanders have homogenized their speech, eroding the once unacceptable drawl as well as the once superior vowels.

ニュージーランド英語は,英語母語話者が入植した当初のイギリス諸島由来の諸方言をベースとしつつも,対蹠地の兄弟としてのオーストラリア英語の影響を被り,さらに土着のマオリ語の語彙も多く借用しながら混交してきた.オーストラリア英語と同様に,一般に Cockney の影響の強い変種とみられることが多いが,それは「Cockney =非標準的な諸変種」という大雑把すぎる前提に基づいた誤解である可能性が高い.ニュージーランドでは,20世紀にかけて前世紀までに行なわれていた様々な変種が水平化し,現代につらなるニュージーランドらしい英語変種が生まれてきた,と考えられる.

・ Lucas, Bill and Christopher Mulvey. A History of the English Language in 100 Places. London: Robert Hale, 2013.

2023-12-12 Tue

■ #5342. 切り取り (clipping) による語形成の類型論 [word_formation][shortening][abbreviation][clipping][terminology][polysemy][homonymy][morphology][typology][apostrophe][hypocorism][name_project][onomastics][personal_name][australian_english][new_zealand_english][emode][ame_bre]

語形成としての切り取り (clipping) については,多くの記事で取り上げてきた.とりわけ形態論の立場から「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]) で詳しく紹介した.

先日12月8日の Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio) の配信回にて「#921. 2023年の英単語はコレ --- rizz」と題して,clipping による造語とおぼしき最新の事例を取り上げた.

この配信回では,2023年の Oxford Word of the Year が rizz に決定したというニュースを受け,これが charisma の clipping による短縮形であることを前提として charisma の語源を紹介した.

rizz が charisma の clipping による語形成であることを受け入れるとして,もとの単語の語頭でも語末でもなく真ん中部分が切り出された短縮語である点は特筆に値する.このような語形成は,それほど多くないと見込まれるからだ.「#893. shortening の分類 (1)」 ([2011-10-07-1]) の "Mesonym" で取り上げたように,例がないわけではないが,やはり珍しいには違いない.以下の解説によると "fore-and-aft clipping" と呼んでもよい.

heldio のリスナーからも関連するコメント・質問が寄せられたので,この問題と関連して McArthur の英語学用語辞典より "clipping" を引用しておきたい (223--24) .

CLIPPING [1930s in this sense]. Also clipped form, clipped word, shortening. An abbreviation formed by the loss of word elements, usually syllabic: pro from professional, tec from detective. The process is attested from the 16c (coz from cousin 1559, gent from gentleman 1564); in the early 18c, Swift objected to the reduction of Latin mobile vulgus (the fickle throng) to mob. Clippings can be either selective, relating to one sense of a word only (condo is short for condominium when it refers to accommodation, not to joint sovereignty), or polysemic (rev stands for either revenue or revision, and revs for the revolutions of wheels). There are three kinds of clipping:

(1) Back-clippings, in which an element or elements are taken from the end of a word: ad(vertisement), chimp(anzee), deli(catessen), hippo(potamus), lab(oratory), piano(forte), reg(ulation)s. Back-clipping is common with diminutives formed from personal names Cath(erine) Will(iam). Clippings of names often undergo adaptations: Catherine to the pet forms Cathie, Kate, Katie, William to Willie, Bill, Billy. Sometimes, a clipped name can develop a new sense: willie a euphemism for penis, billy a club or a male goat. Occasionally, the process can be humorously reversed: for example, offering in a British restaurant to pay the william.

(2) Fore-clippings, in which an element or elements are taken from the beginning of a word: ham(burger), omni(bus), violon(cello), heli(copter), alli(gator), tele(phone), earth(quake). They also occur with personal names, sometimes with adaptations: Becky for Rebecca, Drew for Andrew, Ginny for Virginia. At the turn of the century, a fore-clipped word was usually given an opening apostrophe, to mark the loss: 'phone, 'cello, 'gator. This practice is now rare.

(3) Fore-and-aft clippings, in which elements are taken from the beginning and end of a word: in(flu)enza, de(tec)tive. This is commonest with longer personal names: Lex from Alexander, Liz from Elizabeth. Such names often demonstrate the versatility of hypocoristic clippings: Alex, Alec, Lex, Sandy, Zander; Eliza, Liz, Liza, Lizzie, Bess, Betsy, Beth, Betty.

Clippings are not necessarily uniform throughout a language: mathematics becomes maths in BrE and math in AmE. Reverend as a title is usually shortened to Rev or Rev., but is Revd in the house style of Oxford University Press. Back-clippings with -ie and -o are common in AusE and NZE: arvo afternoon, journo journalist. Sometimes clippings become distinct words far removed from the applications of the original full forms: fan in fan club is from fanatic; BrE navvy, a general labourer, is from a 19c use of navigator, the digger of a 'navigation' or canal. . . .

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2015-11-10 Tue

■ #2388. 世界の主要な英語変種の音韻的分類 [world_englishes][model_of_englishes][ame_bre][ame][bre][irish_english][australian_english][new_zealand_english][scots_english][map]

世界の主要な英語変種を分類する試みは,主として社会言語学的な視点から様々になされてきた.本ブログでも,model_of_englishes の記事で取り上げてきた通りである.言語学的な観点からの分類としては,Trudgill and Hannah による音韻に基づくものが知られている.概論的にいえば,大きく 'English' type と 'American' type に2分する方法であり,直感的で素人にも理解しやすい.この常識的に見える分類が,結論としては,専門的な見地からも支持されるということである.この 'American' type と 'English' type の2分法は,より積極的に歴史的な視点を取れば,大雑把にいってイングランド内の 'northern' type と 'southern' type の2分法に相当することに注意したい.

Trudgill and Hannah (10) は,音韻論的に注目すべき鍵として以下の10点を挙げて,英語諸変種を図式化した.

Key

1. /ɑː/ rather than /æ/ in path etc.

2. absence of non-prevocalic /r/

3. close vowels for /æ/ and /ɛ/, monophthongization of /ai/ and /ɑu/

4. front [aː] for /ɑː/ in part etc.

5. absence of contrast of /ɒ/ and /ɔː/ as in cot and caught

6. /æ/ rather than /ɑː/ in can't etc.

7. absence of contrast of /ɒ/ and /ɑː/ as in bother and father

8. consistent voicing of intervocalic /t/

9. unrounded [ɑ] in pot

10. syllabic /r/ in bird

11. absence of contrast of /ʊ/ and /uː/ as in pull and pool

10 9 8 7 6 5 6 7 8 9 11 10 11 5 1 2

| | | | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | Northern | | | | |

| | | | | | Canada | | | | | Ireland | Scotland | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | `----------+----------' | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | `--------+---+---+---+--------------+--------------' | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | `----------, | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | | | | |

| | | | | USA | | | ,----------+---+------------------' |

| | | | | | | | | Republic | | |

| | | | `------------' | | | of | | ,------------------'

| | | | | | | Ireland | | |

| | | `--------------------' | | | | | England ,--------------------------------- 3

| | | | | | | | |

| | | | | | | | Wales | ,----------------------- 4

| | | | | | | | | South | Australia New

| | `----------------------------' | | | | | Africa | Zealand

| | | | | | | `----------------------- 4

| | | | | | |

| `------------------------------------+----------' | | `--------------------------------- 3

| | | |

`----------------------------------------+--------------' `--------------------------------------------- 2

|

`---------------------------------------------------------------- 1

この図の説明として,Trudgill and Hannah (10) を引こう.

We have attempted to portray the relationships between the pronunciations of the major non-Caribbean varieties in [this] Figure 1.1. This diagram is somewhat arbitrary and slightly misleading (there are, for example, accents of USEng which are close to RP than to mid-western US English), but it does show the two main types of pronunciation: an 'English' type (EngEng, WEng, SAfEng, AusEng, NZEng) and an 'American' type (USEng, CanEng), with IrEng falling somewhere between the two and ScotEng being somewhat by itself.

最後に触れられているように,Irish English が2大区分にまたがること,古い歴史をもつ Scots English が独自路線を行っていることは興味深い.

・ Trudgill, Peter and Jean Hannah. International English: A Guide to the Varieties of Standard English. 5th ed. London: Hodder Education, 2008.

2014-03-31 Mon

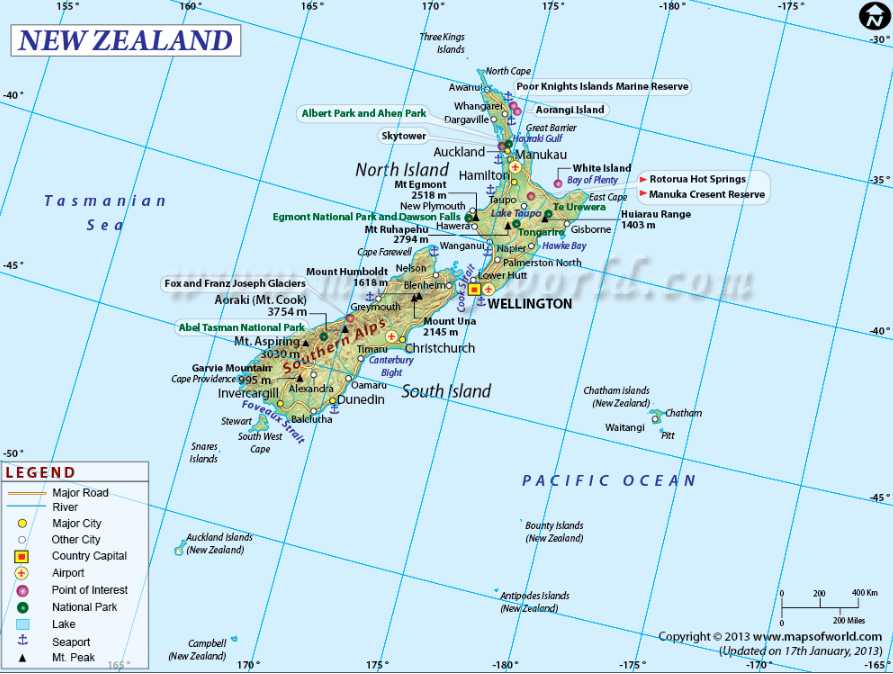

■ #1799. New Zealand における英語の歴史 [history][new_zealand_english][map][maori]

昨日の記事「#1798. Australia における英語の歴史」 ([2014-03-30-1]) に続き,Fennell (247) 及び Svartvik and Leech (105--10) に依拠し,今回はニュージーランドの英語史を略述する.

オーストラリアと異なり,ニュージーランドは囚人流刑地ではなく,入植にもずっと時間がかかった.Captain Cook (1728--79) は,1769年,オーストラリアに達する前にニュージーランドを訪れていた.この土地は,少なくとも600年以上のあいだ先住のマオリ人 (Maori) により住まわれており,Aotearoa と呼ばれていた.1790年代にはヨーロッパ人の捕鯨船員や商人が往来し,1814年には宣教師が先住民への布教を開始したが,イギリス人による本格的な関与は19世紀半ばからである.1840年,イギリス政府はマオリ族長とワイタンギ条約 (Treaty of Waitangi) を結び,ニュージーランドを公式に併合した.当初の移民人口は約2,100人だったが,1850年までにその数は25,000人に増加し,1900年までには25万人の移民がニュージーランドに渡っていた(現在の人口は400万人ほど).特に南島にはスコットランド移民が多く,Ben Nevis, Invercargill, Dunedin などの地名にその痕跡を色濃く残している.1861年の金鉱の発見によりオーストラリア人が大挙するなど移民の混交もあったが,世紀末にはオーストラリア変種に似通ってはいるものの独自の変種が立ち現れてきた.

ニュージーランド英語の主たる特徴は,マオリ語からの豊富な借用語にある.ニュージーランド英語の1000語のうち6語がマオリ語起源ともいわれる.例えば,木の名前として kauri, totara, rimu,鳥の名前として kiwi, tui, moa, 魚の名前として tarakihi, moki などがある.このような借用語の豊富さは,マオリ語が1987年より英語と並んで公用語の地位を与えられ,公的に振興が図られていることとも無縁ではない(「#278. ニュージーランドにおけるマオリ語の活性化」 ([2010-01-30-1]) を参照).ニュージーランド英語の辞書として,The Dictionary of New Zealand English や The New Zealand Oxford Dictionary を参照されたい.

ニュージーランド人は,オーストラリア人に比べて,イギリス人に対して共感の意識が強く,アメリカ人に対して反感が強いといわれる.RP (Received Pronunciation) の威信も根強い.しかしこの伝統的な傾向も徐々に変化してきており,若い世代ではアメリカ英語の影響が強い.

ニュージーランドの言語事情については,Ethnologue より New Zealand を参照.

・ Fennell, Barbara A. A History of English: A Sociolinguistic Approach. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2001.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 144--49.

2011-12-18 Sun

■ #965. z の文字の発音 (2) [z][alphabet][ame_bre][alphabet][new_zealand_english][americanism]

昨日の記事「#964 z の文字の発音 (1)」 ([2011-12-17-1]) の話題について,もう少し調べてみたので,その報告.

アメリカ英語での zee としての発音について,Mencken (445) が次のように述べている.

The name of the last letter of the alphabet, which is always zed in England and Canada, is zee in the United States. Thornton shows that this Americanism arose in the Eighteenth Century.

この記述だと,zee の発音はアメリカ英語独自の刷新ということになるが,昨日も触れたように,zee の発音は周辺的ではあったが近代英語期のイギリス英語にれっきとして存在していたのだから,誤った記述,少なくとも誤解を招く記述である.より正しくは,Cassidy and Hall (191) の記述を参考にすべきだろう.

Though zed is now the regular English form, z had also been pronounced zee from the seventeenth century in England. Both forms were taken to America, but evidently New Englanders favored zee. When, in his American Dictionary of the English Language (1828), Noah Webster wrote flatly, "It is pronounced zee," he was not merely flouting English preference for zed but accepting an American fait accompli. The split had already come about and continues today.

昨日も記した通り,歴史的には z の発音の variation は英米いずれの変種にも存在したが,近代以降の歴史で,各変種の標準的な発音としてたまたま別の発音が選択された,ということである.アメリカ英語独自あるいはイギリス英語独自という言語項目は信じられているほど多くなく,むしろかつての variation の選択に際する相違とみるべき例が多いことに注意したい.

なお,ニュージーランド英語では,近年,若年層を中心に,伝統的なイギリス発音 zed に代わって,アメリカ発音 zee が広がってきているという.Bailey (492) より引用しよう.

In data compiled in the 1980s, children younger than eleven offered zee as the name of the last letter of the alphabet while all those older than thirty responded with zed.

・ Mencken, H. L. The American Language. Abridged ed. New York: Knopf, 1963.

・ Cassidy Frederic G. and Joan Houston Hall. "Americanisms." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 184--252.

・ Bailey, Richard W. "American English Abroad." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 6. Cambridge: CUP, 2001. 456--96.

2010-06-03 Thu

■ #402. Southern Hemisphere Shift [gvs][vowel][language_change][new_zealand_english][australian_english][south_africa]

[2010-05-28-1]の記事で米国の北部都市で起こっている短母音の体系的推移である Northern Cities Shift に触れた.NCS は非常に稀な短母音推移の例として英語史的な意義を付与されることがあるが,実のところ体系的な短母音推移は英語の他の変種でも起こっている.例えば Australian English ( AusE ), New Zealand English ( NZE ), South African English ( SAE ) の主要変種に共通して生じている短母音推移 ( Southern Hemisphere Shift ) が挙げられる.SHS では,以下のような連鎖的な推移 ( chain shift ) が認められる.

/æ/ -> /e/ -> /ɪ/ -> /i/ or /ə/

/ɪ/ が推移する先は,AusE では /i/,NZE では /ə/ になるという差異はあるが,全体として南半球としてまとめてよい程度に共通している.電話口で父親を出してくれと言われて父親に受話器を渡すとき,Here's Dad というところが He's dead の発音になってしまうので注意が必要である.

個人的な体験としては,しばらく New Zealand に滞在していたときに,bread が /brɪd/ あるいは /bri:d/ とすら発音されているのにとまどった.パンのことを言っているのだと気付くまでにしばらくかかった.また,滞在先にいた小学生に Sega のテレビゲームを一緒にやろうと誘われているのを cigar と聞き違えて,何か麻薬の誘いだろうかと驚いたこともある.

英語史上に有名な,長母音に生じた大母音推移 Great Vowel Shift ([2009-11-18-1]) の陰で,短母音系列の推移は目立たない.確かに長母音に比べると安定しているのは確かなようだが,標準的な変種から一歩離れてみてみると NCS や SHS の例がみられる.稀な単母音推移として NCS や SHS に付与される英語史上の意義というのも,どの変種を英語史の代表選手と考えるかによって価値が変わってくる相対的な意義であることを確認しておく必要があるだろう.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 108--09.

2010-01-30 Sat

■ #278. ニュージーランドにおけるマオリ語の活性化 [language_death][revitalisation_of_language][maori][new_zealand_english][linguistic_right]

ENL 国の一つ New Zealand で,ここ40年ほど,先住民マオリの言語 Maori が活性化してきている.

近年の言語多様性の意識の高まりとともに,地域の少数派言語が復興運動を通じて活性化する例は世界にあるが,Welsh と並んで著名な例が Maori である.一般論として言語復興運動の成功の鍵がどこにあるのか,そしてこれから言語復興運動を始めようとする場合にどのような戦略を立てるべきかは未開拓の研究分野だが,成功している例を参考にすべきことはいうまでもない.

In the case of the Maori of New Zealand, a different cluster of factors seems to have been operative, involving a strong ethnic community involvement since the 1970s, a long-established (over 150 years) literacy presence among the Maori, a government educational policy which has brought Maori courses into schools and other centres, such as the kohanga reo ('language nests'), and a steadily growing sympathy from the English-speaking majority. Also to be noted is the fact that Maori is the only indigenous language of the country, so that it has been able to claim the exclusive attention of those concerned with language rights. (Crystal 128--29)

Maori の場合には,(1) マオリの確固たる共同体意識,(2) マオリの識字水準の高さ,(3) 政府の好意的な教育政策,(4) 周囲の多数派である英語母語話者の理解,(5) 他の少数派言語が存在しないこと,という社会的条件がすばらしく整っていることが成功につながっているようだ.

[2010-01-26-1]の記事で触れたように,今後100年で約3000の言語が消滅するおそれがあることを考えるとき,その大多数についてこのような好条件の整う可能性は絶望的だろう.だが,(1) や (4) の意識改革の部分には一縷の希望があるのではないか.自分自身,言語研究に携わる者として,この点に少しでも貢献できればと考える.

今回の話題は直接に英語に関する話題ではないが,今後の英語のあり方を考える上で,共生する言語との関係を斟酌しておくことは linguistic ecology の観点からも重要だろう.Crystal (32, 94, 98) によれば,最近は ecology of language や ecolinguistics という概念が提唱されてきており,言語にも「エコ」の時代が到来しつつあるようだ.

・Crystal, David. Language Death. Cambridge: CUP, 2000.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow