2017-05-19 Fri

■ #2944. ship, skiff, skip(per) [doublet][etymology][phonetics][palatalisation][consonant][digraph][cognate][germanic][sgcs][loan_word][dutch]

「#1511. 古英語期の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化」 ([2013-06-16-1]) でみたように,ゲルマン語の [sk] は後期古英語期に口蓋化と歯擦化を経て [ʃ] へと変化した.後者は,古英語では scip (ship) のように <sc> という二重字 (digraph) で綴られたが,「#2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史」 ([2014-12-06-1]) で説明したとおり,中英語期には新しい二重字 <sh> で綴られるようになった.

ゲルマン諸語の同根語においては [sk] を保っていることが多いので,これらが英語に借用されると,英語本来語とともに二重語 (doublet) を形成することになる.英語本来語の shirt と古ノルド語からの skirt の関係がよく知られているが,標題に挙げた ship, skiff, skip(per) のような三重語ともいうべき関係すら見つけることができる.

「船」を意味する古高地ドイツ語の単語は scif,現代ドイツ語では Schiff である.語末子音 [f] は,第2次ゲルマン子音推移 (sgcs) の結果だ.古高地ドイツ語 sciff は古イタリア語へ schifo として借用され,さらに古フランス語 esquif を経て中英語へ skif として小型軽装帆船を意味する語として入った.これが,現代英語の skiff である.フランス語の equip (艤装する)も関連語だ.

一方,語頭の [sk] を保った中オランダ語の schip に接尾辞が付加した skipper は,小型船の船長を意味する語として中英語に入り,現在に至る.この語形の接尾辞部分が短縮され,結局は skip ともなり得るので,ここでみごとに三重語が完成である.skipper については,「#2645. オランダ語から借用された馴染みのある英単語」 ([2016-07-24-1]) も参照.

なお,語根はギリシア語 skaptein (くり抜く)と共通しており,木をくりぬいて作った丸木船のイメージにつながる.

2016-05-30 Mon

■ #2590. <gh> を含む単語についての統計 [statistics][spelling][grapheme][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph][gh]

標記について,辻前が,Jones の English Pronouncing Dictionary (12th ed.) を用いて,<gh> を含む固有名詞,派生語,複合語を除いた90語を対象とした調査を行なっている.以下に,辻前 (145--46) が結論部で整理して示している数字を示したい.

1. Spelling について

(1) Digraph 'gh' の位置による分類

語頭にある語 6 (7%) 語中にある語 19 (21%) 語尾にある語 (-t を含む) 65 (72%)

語頭に 'gh' がくる語はすべて gh [g] 音である.

(2) 母音字による分類

- ough(t) を含む語 29 73 -igh(t) を含む語 24 -augh(t) を含む語 10 -eigh(t) を含む語 10 その他 17

2. Sound について

(1) 'gh' 音による分類

gh [g] 音語 14 (16%) gh [f] 音語 10 (10%) gh-mute 語 62 (70%) その他の音 4 (4%)

'gh' [g] 音語は不必要に作られたか,借用語である.正規の変化によるものとしては [f] 音語が一割ある外はほとんど黙字であるといえる.

(2) gh-mute 語の分類

[-ait] となる語 25 54 [ɔːt] となる語 19 [-eit] となる語 10 その他の音 8

正規の音声変化が立証されるとともに,この点で 'gh' digraph と母音との関係が密接であったことに注目すべきであろう.

(3) 音節による分類

単音節語 68 (76%) 2音節語 19 (21%) 3音節語 3 (3%)

'gh' word は単音節で frequency の高い基本語が多く,逆に多音節語はほとんどが特殊な輸入語である.

結論としては,<gh> を含む単語では,though や thought のような単語が最も典型的である.7割ほどが,単音節語であるか,語尾に問題の2重字をもつか,無音に対応するかである.

<gh> に関連する話題として,「#15. Bernard Shaw が言ったかどうかは "ghotiy" ?」 ([2009-05-13-1]),「#210. 綴字と発音の乖離をだしにした詩」 ([2009-11-23-1]),「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1]),「#1902. 綴字の標準化における時間上,空間上の皮肉」 ([2014-07-12-1]),「#1936. 聞き手主体で生じる言語変化」 ([2014-08-15-1]),「#2085. <ough> の音価」 ([2015-01-11-1]) などの記事も参照.

・ 辻前 秀雄 「Digraph 'gh' 発達に関する史的考察」『甲南女子大学研究紀要』第4巻,1967年.128--47頁.

2016-03-19 Sat

■ #2518. 子音字の黙字 [silent_letter][phoneme][grapheme][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][consonant][phonology][orthography][digraph][statistics][haplology][spelling_pronunciation]

磯部 (118) の調べによると,現代英語の正書法において子音字が黙字 (silent_letter) を含む語形は,派生語や屈折形を含めて420語あるという.子音字別に内訳を示すと以下の通り.<b> (24 words), <c> (11), <ch> (4), <d> (17), <f> (2), <g> (41), <gh> (41), <h> (57), <k> (11), <l> (67), <m> (1), <n> (14), <s> (22), <p> (31), <ph> (2), <r> (1), <t> (37), <th> (2), <w> (33), <x> (2) .磯部論文では,これらの具体例がひたすら挙げられており,壮観である.以下,読んでいておもしろかった点,意外だった例などを独断と偏見で抜き出し,紹介したい.

(1) 語末の <mb> で <b> が黙字となる例は「#34. thumb の綴りと発音」 ([2009-06-01-1]), 「#724. thumb の綴りと発音 (2)」 ([2011-04-21-1]), 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1]),「#1917. numb」 ([2014-07-27-1]) などで挙げてきたが,もう少し例を追加できる.古英語や中英語で <b> (= /b/) はなかったが,後に <b> が挿入されたものとして limb, crumb, numb, thumb がある.一方,かつては実現されていた <b> = /b/ が後に無音化した例として,climb, bomb, lamb, comb, dumb, plumb, succumb がある.<mb> の組み合わせでも,rhomb (菱形), zimb (アブの一種), iamb (弱強格)などの専門用語では <b> が発音されることもある.

(2) 「#2362. haplology」 ([2015-10-15-1]) の他の例として,mineralogy < mineralology, pacifism < pacificism, stipend < stipi-pendium, tragicomedy < tragic comedy がある.

(3) perhaps はくだけた発音では /præps/ となり,<h> は黙字となる.

(4) iron において,アメリカ英語では <r> は発音されるが,イギリス英語では <r> が無音の /ˈaɪən/ となる.

(5) kiln

は綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) の /kɪln/ が普通だが,中英語期に <n> が無音となった歴史的な発音 /kɪl/ もある.同様に Milne も /mɪln/ が普通だが,Jones の発音辞典 (1967) では /mɪl/ のみが認められていたというから,綴字発音はつい最近のことのようだ.

(6) Christmas は注意深い発音では /ˈkrɪstməs/ となり <t> は黙字とならない.このような子音に挟まれた環境では,歴史的に <t> は無音となるのが通常だった (see 「#379. often の spelling pronunciation」 ([2010-05-11-1])) .

(7) 航海用語としての southeast, northeast では <th> は無音となる./saʊ ˈiːst/, /nɔːr ˈiːst/ .

この論文を熟読すると,君も黙字のプロになれる!

・ 磯部 薫 「Silent Consonant Letter の分析―特に英語史の観点から見た場合を中心として―」『福岡大学人文論叢』第5巻第1号, 1973年.117--45頁.

2016-03-17 Thu

■ #2516. 子音音素と子音文字素の対応表 [phoneme][grapheme][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][consonant][phonology][orthography][digraph][statistics]

昨日の記事「#2515. 母音音素と母音文字素の対応表」 ([2016-03-16-1]) に引き続き,磯部 (19--21) を参照して,子音(字)の対応表を掲げる.

| consonantal phoneme | consonantal grapheme の例 | 種類 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /p/ | p, gh, pp, ph, pe | 5 |

| 2 | /b/ | b, bh, bb, pb, be | 5 |

| 3 | /t/ | t, th, pt, ct, ed, tt, bt | 7 |

| 4 | /d/ | d, bd, dh, dd, ed, ddh | 6 |

| 5 | /k/ | k, c, kh, ch, que, qu, cque, cqu, q, cch, cc, ck, che, ke, x, gh, cu | 17 |

| 6 | /q/ | g, gu, gh, gg, gue | 5 |

| 7 | /ʧ/ | ch, tch, t, c, cz, te, ti | 7 |

| 8 | /ʤ/ | j, g, dg, gi, ge, dj, g, di, d, dge, gg, ch | 12 |

| 9 | /f/ | f, ph, gh, ff, v, pph, u, fe | 8 |

| 10 | /v/ | v, f, ph, vv, v | 5 |

| 11 | /θ/ | th | 1 |

| 12 | /ð/ | th | 1 |

| 13 | /s/ | s, sci, c, sch, ce, ps, ss, sw, se | 9 |

| 14 | /z/ | z, se, x, ss, cz, zz, sc | 7 |

| 15 | /ʃ/ | sh, shi, sch, s, si, ss, ssi, ti, ch, ci, ce, sci, chsi, se, c, psh, t | 17 |

| 16 | /ʒ/ | s, z, si, zi, ti, ge | 6 |

| 17 | /h/ | h, wh, x | 3 |

| 18 | /m/ | m, mb, mn, mm, mpd, gm, me | 7 |

| 19 | /n/ | n, mn, ne, pn, kn, gn, nn, mpt, ln, dn | 10 |

| 20 | /ŋ/ | ng, n, ngue, nd, ngh | 5 |

| 21 | /l/ | l, ll, le | 3 |

| 22 | /r/ | r, rh, rrh, rr, wr | 5 |

| 23 | /j/ | y, j, i, ll | 4 |

| 24 | /w/ | w, o, ou, u | 4 |

| 合計 | 159 |

数で見ると,24種類の音素に対して計159種類の文字素(digraph 等を含む)が対応している.平均して1音素を表すのに6.625個の文字素が使用されうるということになる.

昨日取り上げた母音と今日の子音とを合算すると,44種類の音素に対して計400個の文字素(digraph 等を含む)が認められることになり,平均して1音素を表すのに9.09個の文字素が使用されうるということになる.

発音と綴字の組み合わせが多様化してきた歴史的要因については「#2405. 綴字と発音の乖離 --- 英語綴字の不規則性の種類と歴史的要因の整理」 ([2015-11-27-1]) で触れた通りだが,それにしてもよくここまで複雑化してきたものだ.

・ 磯部 薫 「現代英語の単語の spelling と sound のdiscrepancy について―特に英語史の観点から見た orthography と phonology の関係について―」『福岡大学人文論叢』第8巻第1号, 1976年.49--75頁.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2016-03-16 Wed

■ #2515. 母音音素と母音文字素の対応表 [phoneme][grapheme][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][vowel][phonology][orthography][digraph][statistics]

現代英語の音素と文字素の対応について詳細に記述した磯部の論文を入手した.淡々と列挙される事例を眺めていると,いかに漏れのないよう細心の注意を払いつつ例を集め,網羅的に整理しようとしたかという,磯部の姿勢が伝わってくる.今回は,磯部 (18--19) に掲げられている母音に関する音素と文字素の対応表を再現したい.各々の対応を含む実際の語例については,直接論文に当たっていただきたい

| vocalic phoneme | vocalic grapheme の例 | 種類 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | /i/ | ee, ea, e, e...e, ei, ie. eo, i, ae, oe, ay, ey, eau, e, ui | 15 |

| 2 | /ɪ/ | i, ie, e, y, o, ui, ee, u, ay, ea, ei, ia, ai, a, ey, eight | 16 |

| 3 | /e/ | e, ea, ai, ay, eo, ie, ei, u, eh, ey, ae, egm, a, oe | 15 |

| 4 | /æ/ | a, ai | 2 |

| 5 | /ʌ/ | u, o, ou, oo, oe, ow | 6 |

| 6 | /ɑ/ | are, ah, al, ar, a, er, au, aa, ear, aar, ir | 11 |

| 7 | /ɐ/ | o, a, ow, ou, au, ach | 6 |

| 8 | /ɔ/ | aw, a, al, au, ough, oa, or, our, oo, ore, oar, as, o, augh | 15 |

| 9 | /ʊ/ | oo, o, ou, oul, oe, or | 7 |

| 10 | /uː/ | oo, o, o...e, u, wo, oe, ou, uh, ough, ow, ui, eux, ioux, eu, ew, ieu, ue, oeu | 18 |

| 11 | /ɜ/ | ur, urr, ear, ir, err, er, or, olo, our, eur, yr, yrrh | 12 |

| 12 | /ə/ | a, u, ar, o, e, ia, i, ough, gh, ou, er, o(u)r, or, ei, ure, eon, oi, or, oar | 19 |

| 13 | /eɪ/ | a...e, a, ea, ai, ei, ay, ao, eh, ey, eigh, ag, aig, e, alf, aa, au, ae, oi, e, et | 20 |

| 14 | /ɑɪ/ | i, i...e, eye, ay, ie, y, igh, uy, y...e, ign, ye, eigh, is, ui, oi, ey, ei, ais | 19 |

| 15 | /ɔɪ/ | oi, oy, eu, uoy | 4 |

| 16 | /əʊ/ | o...e, ol, ow, oh, owe, o, ou, oa, oe, eo, ew, ough, eau, au, ogn | 16 |

| 17 | /aʊ/ | ow, aou, ou, eo, au, ough, iaour | 7 |

| 18 | /ɪə/ | ear, eer, ia, ere, eir, ier, a, ea, eu, iu, e, eou, eor, iou, io, ir | 16 |

| 19 | /eə/ | are, air, ear, eir, ere, aire, ar, ayor | 8 |

| 20 | /ʊə/ | uo, oer, oor, ure, our, ua, ue, we, uou | 9 |

| 合計 | 241 |

この発音の分類では強勢・無強勢音節の区別が考慮されておらず,解釈に注意を要する点はあるが,これまでにみてきた類似の対応表のなかでも相当に網羅的な部類といっていいだろう.

数でいえば,20種類の音素に対して計241種類の文字素(digraph 等を含む)が対応している.平均して1音素を表すのに12.05個の文字素が使用されうるということになる.

・ 磯部 薫 「現代英語の単語の spelling と sound のdiscrepancy について―特に英語史の観点から見た orthography と phonology の関係について―」『福岡大学人文論叢』第8巻第1号, 1976年.49--75頁.

2015-12-17 Thu

■ #2425. 書き言葉における母音長短の区別の手段あれこれ [writing][digraph][grapheme][orthography][phoneme][ipa][katakana][hiragana][diacritical_mark][punctuation][final_e]

昨日の記事「#2424. digraph の問題 (2)」 ([2015-12-16-1]) では,二重字 (digraph) あるいは複合文字素 (compound grapheme) としての <th> を題材として取り上げ,第2文字素 <h> が発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]) として用いられているという見方を紹介した.また,それと対比的に,日本語の濁点やフランス語のアクサンを取り上げた.その上で,濁点やアクサンがあくまで見栄えも補助的であるのに対して,英語の <h> はそれ自体で単独文字素としても用いられるという差異を指摘した.もちろん,いずれかの方法を称揚しているわけでも非難しているわけでもない.書記言語によって,似たような発音区別機能を果たすべく,異なる手段が用意されているものだということを主張したかっただけである.

この点について例を挙げながら改めて考えてみたい.短母音 /e/ と長母音 /eː/ を区別したい場合に,書記上どのような方法があるかを例に取ろう.まず,そもそも書記上の区別をしないという選択肢があり得る.ラテン語で短母音をもつ edo (I eat) と長母音をもつ edo (I give out) がその例である.初級ラテン語などでは,初学者に判りやすいように前者を edō,後者を ēdō と表記することはあるが,現実の古典ラテン語テキストにおいてはそのような長音記号 (macron) は現われない.母音の長短,そしていずれの単語であるかは,文脈で判断させるのがラテン語流だった.同様に,日本語の「衛門」(えもん)と「衛兵」(えいへい)における「衛」においても,問題の母音の長短は明示的に示されていない.

次に,発音区別符号や補助記号を用いて,長音であることを示すという方法がある.上述のラテン語初学者用の長音記号がまさにその例だし,中英語などでも母音の上にアクサンを付すことで,長音を示すという慣習が一部行われていた.また,初期近代英語期の Richard Hodges による教育的綴字にもウムラウト記号が導入されていた (see 「#2002. Richard Hodges の綴字改革ならぬ綴字教育」 ([2014-10-20-1])) .これらと似たような例として,片仮名における「エ」に対する「エー」に見られる長音符(音引き)も挙げられる.しかし,「ー」は「エ」と同様にしっかり1文字分のスペースを取るという点で,少なくとも見栄えはラテン語長音記号やアクサンほど補助的ではない.この点では,IPA (International Phonetic Alphabet; 国際音標文字)の長音記号 /ː/ も「ー」に似ているといえる.ここで挙げた各種の符号は,それ単独では意味をなさず,必ず機能的にメインの文字に従属するかたちで用いられていることに注意したい.

続いて,平仮名の「ええ」のように,同じ文字を繰り返すという方法がある.英語でも中英語では met /met/ に対して meet /meːt/ などと文字を繰り返すことは普通に見られた.

また,「#2423. digraph の問題 (1)」 ([2015-12-15-1]) でも取り上げたような,不連続複合文字素 (discontinuous compound grapheme) の使用がある.中英語から初期近代英語にかけて行われたが,red /red/ と rede /reːd/ のような書記上の対立である.rede の2つ目の <e> が1つ目の <e> の長さを遠隔操作にて決定している.

最後に,ギリシア語ではまったく異なる文字を用い,短母音を ε で,長母音を η で表わす.

このように,書記言語によって手段こそ異なれ,ほぼ同じ機能が何らかの方法で実装されている(あるいは,いない)のである.

2015-12-16 Wed

■ #2424. digraph の問題 (2) [alphabet][grammatology][writing][digraph][spelling][grapheme][orthography][phoneme][diacritical_mark][punctuation]

昨日の記事 ([2015-12-15-1]) に引き続いての話題.現代英語の二重字 (digraph) あるいは複合文字素 (compound grapheme) のうち,<ch>, <gh>, <ph>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> のように2つめの文字素が <h> であるものは少なくない.すべてにあてはまるわけではないが,共時的にいって,この <h> の機能は,第1文字素が表わす典型的な子音音素のもつ何らかの弁別特徴 (distinctive feature) を変化させるというものだ.前舌化・破擦音化したり,摩擦音化したり,口蓋化したり,歯音化したり,無声化したり等々.その変化のさせかたは一定していないが,第1文字素に対応する音素を緩く「いじる」機能をもっているとみることができる.音素より下のレベルの弁別特徴に働きかける機能をもっているという意味においては,<h> は機能的には独立した文字というよりは発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]) に近い.このように機能としては補助的でありながら,体裁としては独立した文字素 <h> を騙っているという点が,あなどれない.

日本語の仮名に付す発音区別符号である濁点を考えよう.メインの文字素「か」の右肩に,さほど目立たないように濁点を加えると「が」となる.この濁点は,濁音性(有声性)という弁別特徴に働きかけており,機能としては上述の <h> と類似している.同様に,フランス語の正書法における <é>, <è>, <ê> などのアクサンも,メインとなる文字素 <e> に補助的に付加して,やや閉じた調音,やや開いた調音,やや長い調音などを標示することがある.つまり,メインの音価の質量にちょっとした改変を加えるという補助的な機能を果たしている.日本語の濁点やフランス語のアクサンは,このように,機能が補助的であるのと同様に,見栄えにおいてもあくまで補助的で,慎ましいのである.

ところが,複合文字素 <th> における <h> は事情が異なる.<h> は,単独でも文字素として機能しうる.<h> はメインもサブも務められるのに対し,濁点やアクサンは単独でメインを務めることはできない.換言すれば,日本語やフランス語では,サブの役目に徹する発音区別符号というレベルの単位が存在するが,英語ではそれが存在せず,あくまで視覚的に卓立した <h> という1文字が機能的にはメインのみならずサブにも用いられるということである.昨日に引き続き改めて強調するが,このように英語の正書法では,機能的にレベルの異なるものが,形式上区別なしに用いられているという点が顕著なのである.

なお,2つの異なるレベルを分ける方策として,合字 (ligature) がある.<ae>, <oe> は2つの単独文字素の並びだが,合字 <æ>, <œ> は1つの複合文字素に対応する.いや,この場合,合字はすでに複合文字素であることをやめて,新しい単独文字素になっていると見るべきだろう (see 「#2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe>」 ([2015-12-10-1]),「#2419. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <ae>」 ([2015-12-11-1])) .

2015-12-15 Tue

■ #2423. digraph の問題 (1) [alphabet][grammatology][writing][digraph][spelling][grapheme][terminology][orthography][final_e][vowel][consonant][diphthong][phoneme][diacritical_mark][punctuation]

現代英語には <ai>, <ea>, <ie>, <oo>, <ou>, <ch>, <gh>, <ph>, <qu>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> 等々,2文字素で1単位となって特定の音素を表わす二重字 (digraph) が存在する.「#2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史」 ([2014-12-06-1]),「#2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe>」 ([2015-12-10-1]),「#2419. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <ae>」 ([2015-12-11-1]) ほかの記事で取り上げてきたが,今回はこのような digraph の問題について論じたい.beautiful における <eau> などの三重字 (trigraph) やそれ以上の組み合わせもあり得るが,ここで述べる digraph の議論は trigraph などにも当てはまるはずである.

そもそも,ラテン語のために,さらに遡ればギリシア語やセム系の言語のために発達してきた alphabet が,それらとは音韻的にも大きく異なる言語である英語に,そのままうまく適用されるということは,ありようもない.ローマン・アルファベットを初めて受け入れた古英語時代より,音素の数と文字の数は一致しなかったのである.音素のほうが多かったので,それを区別して文字で表記しようとすれば,どうしても複数文字を組み合わせて1つの音素に対応させるというような便法も必要となる.例えば /æːa/, /ʤ/, /ʃ/ は各々 <ea>, <cg>, <sc> と digraph で表記された (see 「#17. 注意すべき古英語の綴りと発音」 ([2009-05-15-1])) .つまり,英語がローマン・アルファベットで書き表されることになった最初の段階から,digraph のような文字の組み合わせが生じることは,半ば不可避だったと考えられる.英語アルファベットは,この当初からの問題を引き継ぎつつ,多様な改変を加えられながら中英語,近代英語,現代英語へと発展していった.

次に "digraph" という用語についてである.この呼称はどちらかといえば文字素が2つ組み合わさったという形式的な側面に焦点が当てられているが,2つで1つの音素に対応するという機能的な側面を強調する場合,"compound grapheme" (Robert 14) という用語が適切だろう.Robert (14) の説明に耳を傾けよう.

We term ai in French faire or th in English thither, compound graphemes, because they function as units in representing single phonemes, but are further divisible into units (a, i, t, h) which are significant within their respective graphemic systems.

compound grapheme (複合文字素)は連続した2文字である必要もなく,"[d]iscontinuous compound grapheme" (不連続複合文字素)もありうる.現代英語の「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1]) がその例であり,<name> や <site> において,<a .. e> と <i .. e> の不連続な組み合わせにより2重母音音素 /eɪ/ と /aɪ/ が表わされている.

複合文字素の正書法上の問題は,次の点にある.Robert も上の引用で示唆しているように,<th> という複合文字素は,単一文字素 <t> と <h> の組み合わさった体裁をしていながら,単一文字素に相当する機能を果たしているという事実がある.<t> も <h> も単体で文字素として特定の1音素を表わす機能を有するが,それと同時に,合体した場合には,予想される2音素ではなく新しい別の1音素にも対応するのだ.この指摘は,複合文字素の問題というよりは,それの定義そのもののように聞こえるかもしれない.しかし,ここで強調したいのは,文字列が横一列にフラットに表記される現行の英語書記においては,<th> という文字列を見たときに,(1) 2つの単一文字素 <t>, <h> が個別の資格でこの順に並んだものなのか,あるいは (2) 1つの複合文字素 <th> が現われているのか,すぐに判断できないということだ.(1) と (2) は文字素論上のレベルが異なっており,何らかの書き分けがあってもよさそうなものだが,いずれもフラットに th と表記される.例えば,<catham> と <catholic> において,同じ見栄えの <th> でも前者は (1),後者は (2) として機能している.(*)<cat-ham>, *<ca(th)olic> などと,丁寧に区別する正書法があってもよさそうだが,一般的には行われていない.これを難なく読み分けられる読み手は,文字素論的な判断を下す前に,形態素の区切りがどこであるかという判断,あるいは語としての認知を先に済ませているのである.言い換えれば,英語式の複合文字素の使用は,部分的であれ,綴字に表形態素性が備わっていることの証左である.

この「複合文字素の問題」はそれほど頻繁に生じるわけでもなく,現実的にはたいして大きな問題ではないかもしれない.しかし,体裁は同じ <th> に見えながらも,2つの異なるレベルで機能している可能性があるということは,文字素論上留意すべき点であることは認めなければならない.機能的にレベルの異なるものが,形式上区別なしにフラットに並べられ得るという点が重要である.

・ Hall, Robert A., Jr. "A Theory of Graphemics." Acta Linguistica 8 (1960): 13--20.

2015-12-11 Fri

■ #2419. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <ae> [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][greek][loan_word][diphthong][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph]

昨日の記事「#2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe>」 ([2015-12-10-1]) に引き続き,今回は <ae> の綴字について,Upward and Davidson (219--20) を参照しつつ取り上げる.

ギリシア語 <oi> が古典期ラテン語までに <oe> として取り入れられるようになっていたのと同様に,ギリシア語 <ai> はラテン語へは <ae> として取り入れられた (ex. G aigis > L aegis) .この二重字 (digraph) で表わされた2重母音は古典期以降のラテン語で滑化したため,綴字上も <ae> に代わり <e> 単体で表わされるようになった.したがって,英語では,古典期以降のラテン語やフランス語などから入った語においては <e> を示すが,古典ラテン語を直接参照しての借用語や綴り直しにおいては <ae> を示すようになった.だが,単語によっては,ギリシア語のオリジナルの <oi> と合わせて,3種の綴字の可能性が現代にも残っている例がある (ex. daimon, daemon, demon; cainozoic, caenozoic, cenozoic) .

近代英語では <ae> で綴られることもあったが,後に <e> へと単純化して定着した語も少なくない.(a)enigma, (a)ether, h(a)eresy, hy(a)ena, ph(a)enomenon, sph(a)ere などである.一方,いまだに根強く <ae> を保持しているのは,イギリス綴字における専門語彙である.aegis, aeon, aesthetic, aetiology, anaemia, archaeology, gynaecology, haemorrhage, orthopaedic, palaeography, paediatrics などがその例となるが,アメリカ綴字では <e> へ単純化することが多い.Michael という人名も,<ae> を保守している.

なお,20世紀までは,<oe> が合字 (ligature) <œ> として印刷されることが普通だったのと同様に,<ae> も通常 <æ> として印刷されていた.また,aerial が合字 <æ> や単字 <e> で綴られることがないのは,これがギリシア語の aerios に遡るものであり,2重字 <ai> に由来するものではなく,あくまで個別文字の組み合わせ <a> + <e> に由来するものだからである.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-12-10 Thu

■ #2418. ギリシア・ラテン借用語における <oe> [etymological_respelling][spelling][latin][greek][french][loan_word][diphthong][spelling_pronunciation_gap][digraph]

現代英語の <amoeba>, <Oedipus>, <onomatopoeia> などの綴字に見られる二重字 () の傾向により従来の <e> の代わりに <oe> が採用されたり,後者が再び廃用となるなど,単語によっても揺れがあったようだ.例えば Phoebus, Phoenician, phoenix などは語源的綴字を反映しており,現代まで定着しているが,<comoedy>, <tragoedy> などは定着しなかった.

現代英語の綴字 <oe> の採用の動機づけが,近代以降に借用されたラテン・ギリシア語彙や語源的綴字の傾向にあるとすれば,なぜそれが特定の種類の語彙に偏って観察されるかが説明される.まず,<oe> は,古典語に由来する固有名詞に典型的に見いだされる.Oedipus, Euboea, Phoebe の類いだ.ギリシア・ローマの古典上の事物・概念を表わす語も,当然 <oe> を保持しやすい (ex. oecist, poecile) .科学用語などの専門語彙も,<oe> を例証する典型的な語類である (ex. amoeba, oenothera, oestrus dioecious, diarrhoea, homoeostasis, pharmacopoeia, onomatopoeic) .

なお,<oe> は16世紀以降の印刷において,合字 (ligature) <œ> として表記されることが普通だった.<oe> の発音については,イギリス英語では /iː/ に対応し,アメリカ英語では /i/ あるいは稀に /ɛ/ に対応することを指摘しておこう.また,数は少ないが,フランス借用語に由来する <oe> もあることを言い添えておきたい (ex. oeil-de-boeuf, oeillade, oeuvre) .

以上 OED の o の項からの記述と Upward and Davidson (221--22) を参照して執筆した.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2015-01-18 Sun

■ #2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手 [grammatology][grapheme][vowel][alphabet][greek][latin][spelling][digraph][diacritical_mark]

「#1826. ローマ字は母音の長短を直接示すことができない」 ([2014-04-27-1]) で取り上げた話題をさらに推し進めると,標記のように「アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」と言ってしまうこともできるかもしれない.この背景には3千年を超えるアルファベットの歴史がある.

「#423. アルファベットの歴史」 ([2010-06-24-1]) でみたように,古代ギリシア人は子音文字であるフェニキアのアルファベットを素材として今から3千年ほど前に初めて母音字を創案したとされるが,その創案は,ギリシア語の子音表記にとって余剰的なフェニキア文字のいくつかをギリシア語の母音に当ててみようという,どちらかというと消極的な動機づけに基づいていた.つまり,母音を表す母音字を発明しようという積極的な動機があったわけではない.実際,ギリシア語の様々な母音を正確に表わそうとするならば,フェニキア・アルファベットからのいくつかの余剰的な文字だけでは明らかに数が不足していた.だが,だからといって新たな母音字を作り出すというよりは,あくまで伝統的な文字セットを用いて子音と同時にいくつかの母音「も」表わせるように工夫したということだ.フェニキア文字以後のローマン・アルファベットの歴史的発展の記述を Horobin (48--49) より要約すると,次のようになる.

The Origins of the Roman alphabet lie in the script used by Phoenician traders around 1000 BC. This was a system of twenty-two letters which represented the individual consonant sounds, in a similar way to modern consonantal writing systems like Arabic and Hebrew. The Phoenician system was adopted and modified by the Greeks, who referred to them as 'Phoenician letters' and who added further symbols, while also re-purposing existing consonantal symbols not needed in Greek to represent vowel sounds. The result was a revolutionary new system in which both vowels and consonants were represented, although because the letters used to represent the vowel wounds in Greek were limited to the redundant Phoenician consonants, a mismatch between the number of vowels in speech and writing was created which still affects English today.

この消極的な母音字の創案とその伝統は,そのままエトルリア文字,それからローマ字へも伝わり,結果的には現代英語にもつらなっている.もちろん,英語史を含め,その後ローマ字を用いてきた多くの言語変種の歴史的段階において,母音をより正確に表わす方法は編み出されてきた.英語史に限っても,二重字 (digraph) など文字の組み合わせにより,ある母音を表すということはしばしば行われてきたし,magic <e> (cf. 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])) にみられるような発音区別符(号) (diacritical mark; cf. 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])) 的な <e> の使用によって先行母音の音質や音量を表す試みもなされてきた.だが,現代英語においても,これらの方法は間接的な母音表記にとどまり,ずばり1文字で直接ある母音を表記するという作用は限定的である.数千年という長い時間の歴史的視座に立つのであれば,これはアルファベットが子音文字として始まったことの呪縛とも称されるものかもしれない.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2014-12-06 Sat

■ #2049. <sh> とその異綴字の歴史 [grapheme][alphabet][consonant][spelling][orthography][timeline][ormulum][digraph]

英語史において無声歯茎硬口蓋摩擦音 /ʃ/ は安定的な音素だったといえるが,それを表わす綴字はヴァリエーションが豊富だった.近現代英語では二重字 (digraph) の <sh> が原則だが,とりわけ中英語では様々な異綴字が行われていた.その歴史の概略は「#1893. ヘボン式ローマ字の <sh>, <ch>, <j> はどのくらい英語風か」 ([2014-07-03-1]) で示し,ほかにも「#479. bushel」 ([2010-08-19-1]) や「#1238. アングロ・ノルマン写字生の神話」 ([2012-09-16-1]) の記事で関連する話題に軽く触れてきた.

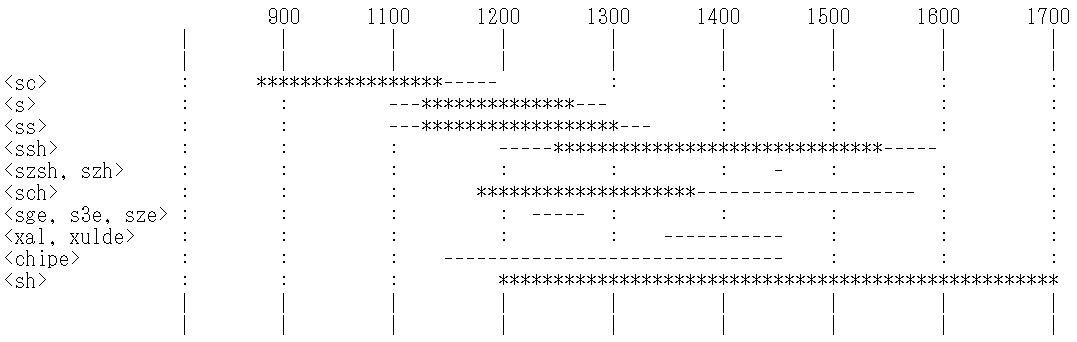

今回は OED sh, n.1 の説明に依拠して,英語史上,問題の子音がどのように綴られてきたのか,もう少し細かく記述したい.まずは,OED の記述に基づいてあらあらの年表を示そう.正確を期しているわけではないので,参考までに.

以下注記を加える.後期古英語の標準綴字だった <sc> は中英語に入ると衰微の一途をたどり,他の種々の異綴字に置き換えられることになった.この子音は当時のフランス語の音素としては存在しなかったため,フランス語で書くことに慣れていた中英語の写字生は,何らかの工夫を強いられることになった.最も単純な試みは単独の <s> を用いる方法で,初期近代英語では語頭と語末の /ʃ/ を表わすのに利用されたが,一般的にはならなかった.その点,重子音字 <ss> は環境を選ばずに用いられたこともあり,より広く用いられた.語中と語末では <ssh> も成功を収め,長く16世紀まで用いられた.16世紀の変わり種としては,Coverdale (1535) でしばしば用いられた <szsh> や <szh> が挙げられるが,あまりに風変わりで真似る者は出なかった.<ss> や <sch> のほかに中英語の半ばで優勢だった異綴字としては,現代ドイツ語綴字を思わせる <sch> を挙げないわけにはいかない.とりわけ語頭では広く行われ,北部方言では16世紀末まで続いた.

特定の語や形態素に現われる /ʃ/ を表わすのに,特定の綴字が用いられたケースがある.例えば she を表わすのに,13世紀には <sge>,

最後に,1200年頃の Ormulum でもすでに規則的に用いられていたが,<sh> が優勢な二重字として他を圧することになる.14世紀末のロンドン文書や Chaucer でも一般的であり,Caxton では標準となった.

近現代英語では,いくつかの語においてこの子音を表わすのに他の字を用いることもあるが,いずれも語源的あるいは発音上説明されるべき周辺的な例である.例えば,machine, schedule, Asia, -tion (cf. 「#2018. <nacio(u)n> → <nation> の綴字変化」 ([2014-11-05-1])) などである.

2014-07-03 Thu

■ #1893. ヘボン式ローマ字の <sh>, <ch>, <j> はどのくらい英語風か [alphabet][japanese][writing][grammatology][orthography][romaji][j][norman_french][digraph]

昨日の記事 ([2014-07-02-1]) の最後に,ヘボン式ローマ字の綴字のなかで,とりわけ英語風と考えられるものとして <sh>, <ch>, <j> の3種を挙げた.現代英語の正書法を参照すれば,これらの綴字が,共時的な意味で「英語風」であることは確かである.しかし,この「英語風」との認識の問題を英語史という立体的な観点から眺めると,問題のとらえ方が変わってくるかもしれない.歴史的には,いずれの綴字も必ずしも英語に本来的とはいえないからである.

まず,<sh> = /ʃ/ が正書法として確立したのは15世紀中頃のことにすぎない.古英語では,この子音は <sc> という二重字 (digraph) で規則的に綴られていた.この二重字は中英語へも引き継がれたが,中英語では様々な異綴りが乱立し,そのなかで埋没していった.例えば,現代英語の <ship> に対応するものとして,中英語では <chip>, <scip>, <schip>, <ship>, <sip>, <ssip> などの綴字がみられる.このなかで,中英語期中最もよく用いられたのは <sch> だろう.現代的な <sh> は,13世紀初頭に Orm が初めてかつ規則的に用いたが,ある程度一般的になったのは14世紀のロンドンで Chaucer などが <sh> を常用するようになってからである.その後,<sh> は15世紀中頃に広く受け入れられるようになり,17世紀までに他の異綴りを廃用へ追い込んだ.このように,二重字 <sh> の慣習は,英語の土壌から発したことは確かだが,中英語期の異綴りとの長い競合の末にようやく定まった慣習であり,英語の規準となってからの歴史はそれほど長いものではない (Upward and Davidson 157) .

次に,<ch> = /ʧ/ の対応の起源は,疑いなく外来である.この子音は,古英語では典型的に前舌母音の前位置に現われ,規則的に <c> で綴られた.しかし,音韻変化の結果,<c> は同じ音韻環境で /k/ をも表わすようになり,二重の役割をもつに至った.この両義性が背景にあったことと,中英語期に Norman French の綴字慣習が広範な影響力をもったことにより,英語では自然と Norman French の <ch> = /ʧ/ が受け入れられる結果となった.12世紀には,早くも古英語的な <c> = /ʧ/ の対応はほとんど廃れ,古英語由来の単語も以降こぞって <ch> で綴り直されるようになった.二重字 <ch> の受容には,文字と音韻の明確な対応を目指す言語内的な要求と,Norman French の綴字習慣の進出という言語外的な要因とが関与しているのである (Upward and Davidson 100) .

<j> については,「#1828. j の文字と音価の対応について再訪」 ([2014-04-29-1]) と「#1650. 文字素としての j の独立」 ([2013-11-02-1]) で見たように,フランス借用語を大量に入れた中英語期に,やはりフランス語の綴字習慣をまねたものが,後に英語でも定着したにすぎない.実際,<j> で始まる英単語は原則として英語本来語ではない.

以上のように,今では「英語風」と認識されている <sh>, <ch>, <j> も,定着するまでは不安定な綴字だったのであり,当初から典型的に「英語風」だったわけではない.<ch> と <j> の2つに至っては,当時のファッショナブルな言語であるフランス語の綴字習慣の模倣であった.英語が当時はやりのフランス語風を受容したように,日本語が現在はやりの英語風を受容したとしても驚くには当たらないだろう.綴字習慣や正書法も,時代の潮流とともに変化することもあれば変異もするのである.そして,言語接触における影響の方向は,流行や威信などの社会言語学的な要因に依存するのが常である.ローマ字の○○式の評価も,歴史的な観点を含めて立体的になされる必要があると考える.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2014-03-27 Thu

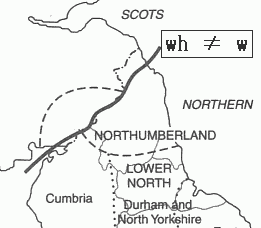

■ #1795. 方言に生き残る wh の発音 [map][pronunciation][dialect][digraph]

「#1783. whole の <w>」 ([2014-03-15-1]) で <wh> の綴字と対応する発音について触れた.現代標準英語では,<wh> も <w> も同様に /w/ に対応し,かつてあった区別はない.しかし,文献によると19世紀後半までは標準変種でも区別がつけられていたし,方言を問題にすれば今でも健在だ.私自身もスコットランド留学中には定常的に /hw/ の発音を聞いていたのを覚えている.<wh> = /hw/ の関係が生きている方言分布についての言及を集めてみた.まずは,Crystal (466) から.

One example is the distinction between a voiced and a voiceless w --- as in Wales vs whales --- which was maintained in educated speech until the second half of the nineteenth century. That the change was taking place during that period is evident from the way people began to notice it and condemn it. For Cardinal Newman's younger brother, Francis, writing in his seventies in 1878, comments: 'W for Hw is an especial disgrace of Southern England.' Today, it is not a feature of Received Pronunciation . . ., though it is kept in several regional accents . . . .

OED の wh, n. によると,次のような記述がある.

In Old English the pronunciation symbolized by hw was probably in the earliest periods a voiced bilabial consonant preceded by a breath. This was developed in two different directions: (1) it was reduced to a simple voiced consonant /w/; (2) by the influence of the accompanying breath, the voiced /w/ became unvoiced. The first of these pronunciations /w/ probably became current first in southern Middle English under the influence of French speakers, whence it spread northwards (but Middle English orthography gives no reliable evidence on this point). It is now universal in English dialect speech except in the four northernmost counties and north Yorkshire, and is the prevailing pronunciation among educated speakers. The second pronunciation, denoted in this Dictionary by the conventional symbol /hw/, . . . is general in Scotland, Ireland, and America, and is used by a large proportion of educated speakers in England, either from social or educational tradition, or from a preference for what is considered a careful or correct pronunciation.

さらに,LPD の "wh Spelling-to-Sound" によれば,

Where the spelling is the digraph wh, the pronunciation in most cases is w, as in white waɪt. An alternative pronunciation, depending on regional, social and stylistic factors, is hw, thus hwaɪt. This h pronunciation is usually in Scottish and Irish English, and decreasingly so in AmE, but not otherwise. (Among those who pronounce simple w, the pronunciation with hw tends to be considered 'better', and so is used by some people in formal styles only.) Learners of EFL are recommended to use plain w.

そして,Trudgill (39) にも.

[The Northumberland area, which also includes some adjacent areas of Cumbria and Durham] is the only area of England . . . to retain the Anglo-Saxon and mediaeval distinction between words like witch and which as 'witch' and 'hwitch'. Elsewhere in the country, the 'hw' sound has been lost and replaced by 'w' so that whales is identical with Wales, what with watt, and so on. This distinction also survives in Scotland, Ireland and parts of North America and New Zealand, but as far as the natural vernacular speech of England is concerned, Northumberland is uniquely conservative in retaining 'hw'. This means that in Northumberland, trade names like Weetabix don't work very well since weet suggests 'weet' /wiːt/ whereas wheat is locally pronounced 'hweet' /hwiːt/.

イングランドに限れば,分布はおよそ以下の地域に限定されるということである.

関連して「#452. イングランド英語の諸方言における r」 ([2010-07-23-1]) も参照.イングランド方言全般については,「#1029. England の現代英語方言区分 (1)」 ([2012-02-20-1]) 及び「#1030. England の現代英語方言区分 (2)」 ([2012-02-21-1]) を参照.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

・ Trudgill, Peter. The Dialects of England. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell, 2000.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow