2020-10-24 Sat

■ #4198. 映画『博士と狂人』を観ました [film][history][lexicography][oed][linguistic_imperialism][philology][comparative_linguistics][hellog_entry_set]

「#4172. 映画『博士と狂人』の原作者による OED 編纂法の紹介文」 ([2020-09-28-1]) で紹介した映画が,先週全国ロードショーとなったので劇場に観に行きました.OED (初版)編纂を巡る人間ドラマです.ネタバレしすぎない程度に,とりあえず感想を一言二言述べておきたいと思います.

・ 原作はノンフィクションだが,映画では少なからずフィクション化されていて,やや趣旨が変わっていたような.逆にいえば,原作が抑え気味だったということ.映画を観たことで,原作のノンフィクションらしい抑制感の魅力に気づいた.

・ OED 編纂を背景とした,実に悲しい話しであることが改めてよく分かった.

・ OED がイギリス帝国としての威信を背負って帝国主義的に企画され,編纂された事実がよく描かれていた.英語(学)史的な観点から,この点はとても重要.授業などで議論したいと思っているポイント.

・ 映画では OED の中身に触れている箇所が少ない(それはそうか)ので,OED の辞書としての凄さが思ったほど伝わらなかったような.映画化するには仕方がないか.もっぱら人間ドラマの描写に集中していた様子.

・ Murray 博士の先輩ともいうべき元 OED 編集主幹にして EETS 設立者でもある Furnivall 役がとても良い味を出していた.原作ではあまり描かれていなかった部分なので,映画でけっこうなお得感があった.やはり,Furnivall は破天荒で魅力的な英語文献学史上の重要キャラ.

・ 「狂人」ことショーン・ペンの演技は迫真だった(メル・ギブソンの「博士」も十分に良かったとはいえ).

上でも触れている OED 編纂と帝国主義の関係については,ぜひ以下の記事を読んでみてください(記事セットとしてはこちらから).OED の見方が変わるかもしれません.

・ 「#304. OED 制作プロジェクトののろし」 ([2010-02-25-1])

・ 「#638. 国家的事業としての OED 編纂」 ([2011-01-25-1])

・ 「#644. OED とヨーロッパのライバル辞書」 ([2011-01-31-1])

・ 「#3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1)」 ([2017-08-03-1])

・ 「#3376. 帝国主義の申し子としての英語文献学」 ([2018-07-25-1])

・ 「#3603. 帝国主義,水族館,辞書」 ([2019-03-09-1])

・ 「#3767. 日本の帝国主義,アイヌ,拓殖博覧会」 ([2019-08-20-1])

・ 「#4131. イギリスの世界帝国化の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes"」 ([2020-08-18-1])

2020-10-05 Mon

■ #4179. 副詞「この頃」は these days なのに副詞「その頃,あの頃」は in those days [sobokunagimon][preposition][adverbial_accusative][adverb][clmet][oed]

大学院生より標記の指摘を受けた(←ナイスな指摘をありがとう).副詞としての「この頃」は前置詞なしの these days が普通なのに対して,「その頃,あの頃」は in those days と前置詞 in を伴う.今までまったく意識したことがなかったが,確かにと唸らされた.このチグハグは何なのだろう.

OED で these days を調べてみると,前置詞を伴わないこの形式は,かなり新しいようだ.初例が1936年となっている.その1世紀足らずの歩みを OED からの4つの例文で示すと次のようになる.

1936 R. Lehmann Weather in Streets i. v. 97 An estate like this must be a terrible problem these days.

1948 M. Dickens Joy & Josephine i. iv. 132 'Play golf?' Mr. Gray asked George, who answered: 'Not these days,' as if he ever had.

1960 S. Barstow Kind of Loving ii. iii. 181 He looks as though he's walked out of an American picture. It's all Yankeeland these days.

1981 Woman 5 Dec. 5/1 These days women are educated to expect some choice in how they spend their lives.

それより前の時代には in these days という前置詞付きの表現が普通だったようだ.後期近代英語コーパス CLMET3.0 でざっと検索してみたところ,次のような結果となった.

| Period (subcorpus size) | in these days | these days |

|---|---|---|

| 1710--1780 (10,480,431 words) | 10 | 0 |

| 1780--1850 (11,285,587) | 56 | 1 |

| 1850--1920 (12,620,207) | 93 | 9 |

ここから,OED が初出年としている1936年よりも前に,前置詞なしの these days も一応使われていたことが分かる.その例文を挙げておこう.

・ (from 1780--1850): Mr. Williams has been here both these days, as usual;

・ (from 1850--1920): SHAWN. Aren't we after making a good bargain, the way we're only waiting these days on Father Reilly's dispensation from the bishops, or the Court of Rome.

・ (from 1850--1920): PEGEEN. If they are itself, you've heard it these days, I'm thinking, and you walking the world telling out your story to young girls or old.

・ (from 1850--1920): "I'm as busy as Trap's wife these days;

・ (from 1850--1920): "My predecessor," said the parson, "played rather havoc with the house. The poor fellow had a dreadful struggle, I was told. You can, unfortunately, expect nothing else these days, when livings have come down so terribly in value! He was a married man--large family!"

・ (from 1850--1920): "He has no right!" Father Wolf began angrily--"By the Law of the Jungle he has no right to change his quarters without due warning. He will frighten every head of game within ten miles, and I--I have to kill for two, these days."

・ (from 1850--1920): "That is because we make you fisherman, these days. If I was you, when I come to Gloucester I would give two, three big candles for my good luck."

・ (from 1850--1920): I have literally not had time to write a line of my diary all these days.

・ (from 1850--1920): "One gets to know that birds have shadows these days. This is a bit open. Let us crawl under those bushes and talk."

・ (from 1850--1920): I do not love to think of my countrymen these days; nor to remember myself.

both や all が先行していると前置詞が不要となる等の要因はあったかもしれない.全体的には,口語的な文脈が多いようだ.in が脱落して現在の形式が現われ始めたのは19世紀後半のこととみてよさそうだ.

2020-09-29 Tue

■ #4173. Palsgrave のフランス語文典 [french][orthoepy][gvs][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_reform][oed][emode]

フランス語研究者であり正音学者だった16世紀前半に活躍したイギリス人 John Palsgrave は,英語(学)史上も重要である.フランス語研究者として1530年に英語でフランス語文典 Lesclarcissement de la Langue Francoyse を著わし,当時もっともよく知られたフランス語文典となった.「#3836. フランス語史の年表」 ([2019-10-28-1]) に名を挙げられるくらいであるから,その影響力はただものではない.

Palsgrave はロンドンに生まれ,ケンブリッジ大学に学び,パリで修士号を取得した.帰国してフランス語教師となり Thomas More などとも親交を深めた.彼の英語学史上の最大の業績は,外国語であるフランス語を「音声表記」した点にあるといってよい.他言語の発音を客観的に記述するという,現代の音声学の基本的な姿勢の伝統を創始した人物である(渡部,p. 38).

16世紀は,Palsgrave のような正音学者が多数輩出した時代である.大母音推移 (gvs) 等の音変化が進行し,発音と綴字のギャップ (spelling_pronunciation_gap) が開きつつあるなかで,綴字改革 (spelling_reform) の訴えが様々な陣営よりなされていた.外国語研究者は発音の問題に敏感である.Palsgrave も,例外ではなく英語の発音と綴字の問題に並々ならぬ関心を示す正音学 (orthoepy) の徒だったのである.なお,外国語研究の立場から英語の発音と綴字の問題に関心を示した初期近代英語期の「同志」としては,ほかに De pronunciation Graecae (1555) を著わした J. Cheke や Grammatica Linguae Anglicanae (1653) を著わした J. Wallis もいる(石橋,p. 616).

Palsgrave のもう1つの注目すべき点は,OED の引用文の常連であることだ.OED は,かの Lesclarcissement から5418個もの用例を引いてきており,この時期の語彙記述に多大な貢献をなしている(cf. 「#642. OED の引用データをコーパスとして使えるか (4)」 ([2011-01-29-1])).この著書は語学書であるから,フィロロジストもである OED 編纂者にとって,当然ながら「大好物」である.編纂者が,このような垂涎ものの著書から(とりわけ文法用語などの)語彙を集めてこないわけがない.

以上,Palsgrave が英語(学)史上ひとかどの人物とされている背景を簡単に紹介した.

・ 渡部 昇一 『英語学史』 英語学大系第13巻,大修館書店,1975年.

・ 石橋 幸太郎(編) 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

2020-09-28 Mon

■ #4172. 映画『博士と狂人』の原作者による OED 編纂法の紹介文 [film][history][lexicography][oed]

OED 編纂を巡る映画『博士と狂人』(原題 The Professor and the Madman)が10月16日(金)に全国ロードショー開始となります.メル・ギブソン(博士 James Murray 役)とショーン・ペン(狂人 Doctor Minor 役)の初共演.「孤高の学者と,呪われた殺人犯.世界最大の英語辞典誕生に隠された,真実の物語」というキャッチです.

原作はノンフィクション作家 Simon Winchester による The Professor and the Madman (1998) .同作家による2003年出版の The Meaning of Everything も,同じく OED 編纂にかかる人間模様を活写しており,抜群におもしろいです.

OED とは何か.これを分かりやすく説明するのは容易ではありませんが,The Professor and the Madman の2章 (25--26) に,著者による導入の文章があるので,引用しておきましょう.OED の編纂法に焦点を当てた導入です.

It took more than seventy years to create the twelve tombstone-size volumes that made up the first edition of what was to become the great Oxford English Dictionary. This heroic, royally dedicated literary masterpiece---which was first called the New English Dictionary, but eventually became the Oxford ditto, and thenceforward was known familiarly by its initials as the OED---was completed in 1928; over the following years there were five supplements and then, half a century later, a second edition that integrated the first and all the subsequent supplementary volumes into one new twenty-volume whole. The book remains in all senses a truly monumental work---and with very little serious argument is still regarded as a paragon, the most definitive of all guides to the language that, for good or ill, has become the lingua franca of the civilized modern world.

Just as English is a very large and complex language, so the OED is a very large and complex book. It defines well over half a million words. It contains scores of millions of characters, and, at least in its early version, many miles of hand-set type. Its enormous---and enormously heavy---volumes are bound in dark blue cloth: Printers and designers and bookbinders worldwide see it as an apotheosis of their art, a handsome and elegant creation that looks and feels more than amply suited to its lexical thoroughness and accuracy.

The OED's guiding principle, the one that has set it apart from most other dictionaries, is its rigorous dependence on gathering quotations from published or otherwise recorded uses of English and using them to illustrate the use of the sense of every single word in the language. The reason behind this unusual and tremendously labor-intensive style of editing and compiling was both bold and simple: By gathering and publishing selected quotations, the dictionary could demonstrate the full range of characteristics of each and every word with a very great degree of precision. Quotations could show exactly how a word has been employed over the centuries; how it has undergone subtle changes of shades of meaning, or spelling, or pronunciation; and, perhaps most important of all, how and more exactly when each word slipped into the language in the first place. No other means of dictionary compilation could do such a thing: Only by finding and showing examples could the full range of a word's past possibilities be explored.

この後も OED 導入の文章が続きますが,ここまででも編纂法のユニークさが分かると思います.物語『博士と狂人』は,OED 編纂法のこのユニークな点を軸に展開していきます.上映が実に楽しみです.

・ Winchester, Simon. The Professor and the Madman: A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary. New York: HarperCollins P, 1998. HarperPerennial ed. 1999.

2020-09-18 Fri

■ #4162. taboo --- 南太平洋発,人類史上最強のパスワード [taboo][cryptography][oed][etymology]

今回の話題は,先日終えたオンライン・ゼミ合宿 (「#4159. 2日間のオンライン・ゼミ合宿を決行しました」 ([2020-09-15-1])) の一環として私自身が参加したハードなイベントの成果物である."taboo" というお題を与えられ,それについて OED を用いて制限時間内に「何かおもしろいこと」を書かなければならないという即興デスマッチだった.後日,少々の手直しを加えたが,およそそのままの形で以下に掲載する.

見るなといわれれば見たくなる.触るなといわれれば触りたくなる.言うなといわれれば言いたくなる.古今東西,この誘惑に打ち勝った童話の主人公はいない.童話の主人公のみならず,人間は誰しも --- あなたも私も --- このマグネットの超強力な引力から逃れることはできない.タブーと称されるものは,人間社会のなかに負のパワーをまき散らしながらも,個々人にとって異常に魅力的な光彩を放っている.

トンガ語を含むポリネシアやメラネシアの諸言語で用いられていた tabu あるいは tapu という語に由来する.18世紀イングランドを代表する大航海者 James Cook (1728--79),通称 Captain Cook が1777年にトンガにてこの語に出会い,その航海日誌のなかで何度も使用した結果,taboo あるいは tabu として英語に持ち込まれることになった.この語は現地語では当地の文化・習慣について「(ある特定の場合にのみ許容されるが)一般に禁じられている」を意味する叙述形容詞として用いられていたが,Cook は当初より形容詞としてのほか,現在もっとも普通の用法である「タブー,禁忌」を意味する名詞として用いている.

taboo はもともと宗教や迷信に基づく各種の習慣に関する「禁忌」,典型的には「食べてはいけないもの」「触ってはいけないもの」などを指した.それが,20世紀前半に言葉(遣い)の領域に適用され,言語学の用語として「言ってはいけないもの」を指すように転じた.すると,私たちにもなじみ深い「タブー語,禁句,忌み詞」の語義は,比較的新しいものということになる.OED によると,「タブー語」としての初例は,taboo | tabu, adj. and n., 3b に挙げられている.名高いアメリカの言語学者 Bloomfield の教科書からである.

1933 L. Bloomfield Language xxii. 396 In America, knocked up is a tabu-form for 'rendered pregnant'; for this reason, the phrase is not used in the British sense 'tired, exhausted' . . . In such cases there is little real ambiguity, but some hearers react nevertheless to the powerful stimulus of the tabu-word.

今回の記事では,Bloomfield が使うこの意味での taboo,すなわち言語に関するタブー --- 言ってはいけない言葉 --- に注目する.

言語は,第1に互いの意図を伝え合うための道具である.私たち人間は,語彙を共有し,共通理解の下でそれを用いながらコミュニケーションを取り合っている.この「言語の第1の役割」を考えるとき,タブー語の存在は明らかに矛盾をはらんでいるように見える.「言ってはいけない言葉」はその社会のなかで不使用が前提とされており,コミュニケーションの目的に照らして,存在意義がないように思われるからだ.

しかし,タブーに関して厳然たる1つの事実が存在する.それは,古今東西の人間の言語で,タブー語をもたないものは存在しないということだ.とすると,タブー語には存在しなければならない理由があると考えざるを得ない.なぜ誰も使用しないはずの「言ってはいけない言葉」などが存在するのだろうか.

タブー語は,建前上,誰も使用しないはずなのだが,実際には皆が知っている.あの言葉を口にしてはいけないということを,社会の皆が知っている.建前上は耳にしたこともなく,学校でも習わないはずであり,知る機会がなさそうに思われる.しかし,不思議と皆が知っている.いや,もし誰も知らなかったら,そもそも語として存在しない(廃語になっている)だろうし,避けるべきものとして意識されることすらないはずだ.実は皆が知っているからこそ,意識的に避けることもできるという理屈なのだ.では,なぜ知る機会のないはずのものを,皆が知っているのだろうか.

上記の逆説に対する答えは「タブー語は実際にはむしろよく使用されている」である.タブー語は,規範として使用が避けられるべき表現にすぎず,現実には頻繁に使用されている.むしろ,タブー化される語は,日常的で身近なもの,つまり人間が生きていくなかで毎日毎日必ず付き合っていかなければならないものに関する語が多い.性,排泄,死,超自然的存在に関するものが多い.日本語では「ち○こ」「う○こ」「(お葬式で)死ぬ」「(霊)アレ」.英語では cock, shit, die, (oh my) God 等も(少なくとも特定の文脈では)遣いにくい.いずれも日常的で身近で,小学生男子が大好きな言葉群である.

性器を表わす英単語を例に取ろう.coney /ˈkʌni/ はもともと「アナウサギ」を表わしたが,後に俗語でタブー性の高い「女性器」に語義を転じた.すると,「アナウサギ」の意味で用いるのに抵抗を感じる話者が増え始め,「アナウサギ」には少しずらした /ˈkoʊni/ の発音を代わりに用いるようになったのである.かわいい「アナウサギ」は,タブー性の強い毒々しい「女性器」に,coney /ˈkʌni/ という発音を明け渡さざるを得なくなったのである.ちなみに,男性器版もある.もともと「雄鳥」を表わしていた cock が,米俗語において性的な語義を獲得するにおよんで,「雄鳥」の語義から追い出され,その語義は rooster という別の語によって担われるようになった.coney にせよ cock にせよ,後からやってきた毒々しいタブー性をもつ語義が,伝統的な形式をふてぶてしくも乗っ取ってしまうということが繰り返されている.

このように,タブー語はたいてい日常的で身近だから,誰しも関心をもっているというのが実態である.その上で,タブー語は何のために存在するのかという核心的な疑問に舞い戻ろう.私見によれば,タブー語は,その言語を用いている社会のすべての構成員が,それは言ってはならない言葉だと知っていることを確認しあう機会を提供しているのではないかということだ.言ってはダメだということを知っていれば,その人は私たちと同じグループに属していることが確認でき,そうでなければ外部の者だと認識できる.「負の合い言葉」と表現してもよい.通常の「正の合い言葉」は,互いに対応する文句を発することによって,直接的にその文句を知っていることを確認し,身内だと認識する.しかし,タブー語という「負の合い言葉」の使用においては,「知っているけれどもあえて言わない」というきわめて高度な内部ルールが関与しているのだ.子供の頃よりその言語社会のなかで生活していない限り,外部の者には簡単に習得できない暗黙知 --- それが社会におけるタブー語の役割なのではないか.タブー語は,コミュニケーションの道具であるという言語の第1の役割を逆手にとりつつ,社会の内と外を分けるための最強のパスワードとして機能しているのである.

21世紀の最先端の量子暗号ですら,「ち○こ」「う○こ」 coney, cock にはかなわない.どうだ,タブー語は凄いだろう!(←我ながらひどい終わり方,力尽きた)

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

・ The Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford: OUP, 2020. Available online at http://www.oed.com/ . Accessed 8 September 2020.

2020-09-15 Tue

■ #4159. 2日間のオンライン・ゼミ合宿を決行しました [hel_education][oed][academic_conference]

先週のことになりますが,例年の2泊3日の対面ゼミ合宿に代えて,本年度は Zoom を用いた初のオンライン・ゼミ合宿を9月8日(火),9日(水)の両日にわたって敢行しました.参加者一同の協力のもと,対面合宿に勝るとも劣らない濃密な英語史漬けの2日間を過ごすことができました.総勢30名近くの参加でしたが,トラブルもなくスムーズに進行しました.

初日の午前は,夏休み中に準備を進めた学部生グループによる「OEDセミナー」の実施に始まり,それを受けて院生による「OEDに関するラウンド・テーブル・ディスカッション」も開催しました.改めてOEDについて深く考える機会となりました.

初日の午後は,参加者一人ひとりがお題としてランダムな英単語を与えられ,90分間でそのお題についてOEDを用いて「何か」を書かなければならないという,デスマッチ的なイベントを行ないました(←私も参加して,果てしなく消耗).そして,晩にかけては例年と変わらぬ懇親会でした(要するに今回はオンライン飲み会).

2日目の午前は,個人研究発表会(いわゆる口頭発表ではなく,昨今のオンライン学会やウェブ・カンファレンスでしばしば見かける,発表資料に音声を付したものを視聴するという形態でしたが).それから,卒業論文執筆予定者を一人ひとり Zoom の小部屋に招き,先輩の院生たちよりアドバイスを受けるという趣旨の,有意義な面談も行ないました.

2日目の午後は,外部より知り合いの研究者を4名お招きし,インフォーマルに英語史について対談を行なうという時間帯を設けました.徐々に対談が乗ってきて,予定の時間をずいぶん延長してしまいました.

企画を詰め込みすぎたかと思うほど盛りだくさんの2日間でしたが,オンラインでも十分に合宿らしいことができるということが分かりました.参加者は皆,知恵熱が出るほど学んだことと思います.私自身も,今回の新スタイルでのゼミ合宿を通じて,参加者の皆さんから広く英語史(とりわけOED)に関して様々なインスピレーションを得たので,その成果は今後の hellog 記事にも徐々に反映していきたいと思います.その意味で,ゼミの学部生・院生を含め参加したすべての方に感謝します.

対面ゼミ合宿はやはり捨てがたいですが,このスタイルでもまたやってみたいと思ったほどです.ということで,お疲れ様でした.

2020-08-31 Mon

■ #4144. 20世紀の語彙爆発 [oed][pde][lexicology][statistics][renaissance]

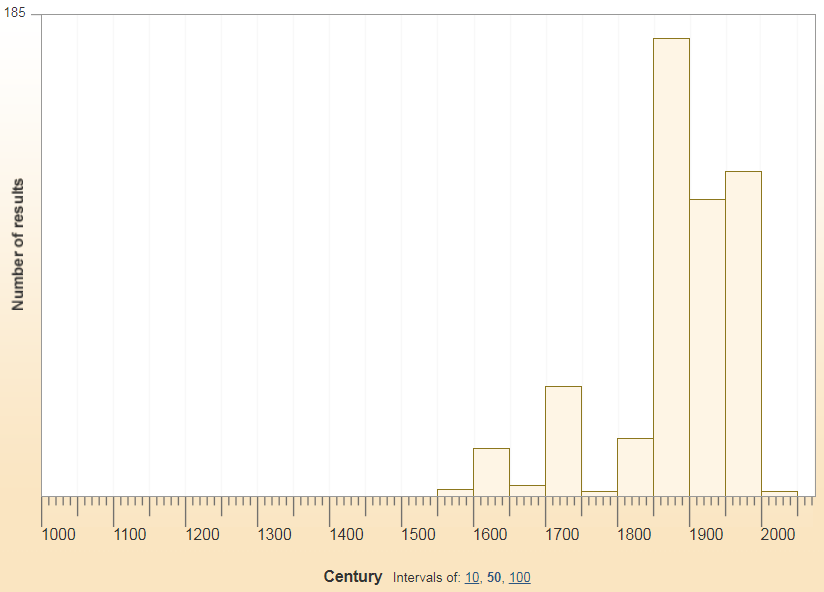

「#4133. OED による英語史概説」 ([2020-08-20-1]) で紹介した OED が運営しているブログに,Twentieth century English --- an overview と題する記事がある.20世紀の英語のすぐれた評論となっており,ぜひ読んでいただきたい.

そのなかの1節 "Lexis: dreadnought and PEP talk" で,20世紀の英語の語彙爆発の様子が具体的な数字とともに記述されている.

The Oxford English Dictionary records about 185,000 new words, and new meanings of old words, that came into the English language between 1900 and 1999. That leaves out of account the so-called lexical 'dark matter', words not common enough to catch the lexicographers' attention or, if they did, to compel inclusion, words perhaps that were never even committed to paper (or any other recording medium). Even so, those 185,000 on their own represent a 25 per cent growth in English vocabulary over the century --- making it the period of most vigorous expansion since that of the late-sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

20世紀中(厳密には1900--1999年)に,OED に採用されたものだけに限っても18万5千もの新語(義)が加わったというのは,想像を絶する爆発ぶりである.引用の後半で触れられている通り,それ以前の時代でいえば,最大級の語彙爆発は1600年前後の英国ルネサンス期にみられた.「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) で見たとおり,Görlach (136) は "The EModE period (especially 1530--1660) exhibits the fastest growth of the vocabulary in the history of the English language, in absolute figures as well as in proportion to the total." と述べている.

20世紀と17世紀では社会の状況も変化速度も大きく異なるので,単純に数字だけでは比較できないが,20世紀は(そしてまだ駆け出しといってよい21世紀もおそらく)英語の語彙爆発の記録を塗り替えた,あるいは塗り替えつつある時代といってよいだろう.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

2020-08-28 Fri

■ #4141. 1150年を越えて残らなかった古英語単語は OED から外されている [oed][oe][doe][periodisation][lexicography][lexicology][manuscript]

OED では古英語の単語はどのように扱われているか.この辺りの話題は,OED Online の提供する Old English in the OED を通じて知ることができる.

OED は,原則として1150年を超えて残らなかった古英語単語は取り扱わないと宣言している.歴史的原則を貫く OED としては,このように除外される単語もれっきとした英単語であるとは認識しているはずだ.しかし,同辞書編纂の長い歴史の当初からの方針であり,別途 The Dictionary of Old English (DOE) も編纂中であることから,現実的な選択肢としてそのような原則を立てているのだろう.それでも,1150年より前に文証され,この境の年を生き延びた7500語ほどの古英語単語が収録されているという事実は指摘しておきたい.

古英語期の内部の時期区分についても,新版 OED では3期に分けるという新しい方針を示している.'early OE' (600--950), 'OE' (950--1100), and 'late OE' (1100--1150) の3期である.主たる古英語写本約200点のうち,ほとんどが 'OE' (950--1100) に由来し,その点で証拠の偏りがあることは致し方がない(それ以前の 'early OE' (600--950) に属するものは20点未満).この3期区分は粗くはあるが,できるかぎり学術的正確性を期すための方法であり,写本年代や語の初出年代の記述にも有効に用いられている.

2020-08-27 Thu

■ #4140. 英語に借用された日本語の「いつ」と「どのくらい」 [oed][japanese][borrowing][loan_word][lexicology][statistics]

「#3872. 英語に借用された主な日本語の借用年代」 ([2019-12-03-1]),「#142. 英語に借用された日本語の分布」 ([2009-09-16-1]) などの記事で見てきたように,英語には意外と多くの日本語単語が入り込んでいる.両言語の接触は16世紀以降のことであり (cf. 「#4131. イギリスの世界帝国化の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes"」 ([2020-08-18-1])),日本語単語の借用は英語史の観点からすると比較的新しい現象とはいえるが,そこそこの存在感を示しているといってよい.このことは「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]),「#126. 7言語による英語への影響の比較」 ([2009-08-31-1]),「#2165. 20世紀後半の借用語ソース」 ([2015-04-01-1]) などでも触れてきた.

OED Online には,様々なパラメータにより,どの時代にどのくらいの単語が英語語彙に加わったかを視覚化してくれる "Timelines" という便利な機能がある.たとえば「日本語が語源である単語」を指定すると,日本語からの借用語が「いつ」「どのくらい」英語に流入したのかを即座にグラフ化してくれる.その結果は以下の通り.

数としては19世紀後半から爆発的に増え始め,現代に至ることがわかる.19世紀後半といえば,もちろん我が国が英米を含む西洋諸国との濃密な接触を開始した幕末・明治維新の時代である.

棒グラフをクリックすると,該当する単語のリストも得られる.ここまで簡単な操作でグラフ化してくれるとは本当に便利な世の中になったなあ.

2020-08-25 Tue

■ #4138. フランス借用語のうち中英語期に借りられたものは4割強で,かつ重要語 [oed][french][latin][loan_word][statistics][lexicology][borrowing]

英語語彙史において,フランス借用語の流入のピークが中英語期にあったことはよく知られている.このことは「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]),「#2162. OED によるフランス語・ラテン語からの借用語の推移」 ([2015-03-29-1]),「#2385. OED による,古典語およびロマンス諸語からの借用語彙の統計 (2)」 ([2015-11-07-1]) などのグラフを見れば,容易に理解できるだろう.

OED が提供している Middle English: an overview の "Borrowing from Latin and/or French" を読んでいたところ,この問題と関連して具体的な数字が挙げられていたので紹介しておきたい.

By 1500, over 40 per cent of all of the words that English has borrowed from French had made a first appearance in the language, including a very high proportion of those French words which have come to play a central part in the vocabulary of modern English. By contrast, the greatest peak of borrowing from Latin was still to come, in the early modern period; by 1500, under 20 per cent of the Latin borrowings found in modern English had yet entered the language.

フランス借用語の流入のピークは中英語期であり,ラテン借用語のピークは近代英語期だったという順序についての指摘はその通りだが,ここで目を引くのは,引用の最初に挙げられている40%強という数字である.現代英語語彙におけるフランス借用語のうち40%強が中英語期の借用であり,しかも現在も中核的な語彙として活躍しているという.言い方をかえれば,この時期に借用されたフランス単語は,古株ながらも現在に至るまで有用性を保ち続けているものが多いということである.残存率が高いと言ってもよい.

それに対するラテン借用語の残存率は,残念ながら数字で表わされていないが,フランス語のそれよりもずっと低いと考えられる.新参者でありながら,現在まで残っていない(あるいは少なくとも有用な語として残っていない)ものが多いのである(cf. 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])).英語史において,このフランス語とラテン語の語彙的影響の差異は興味深い.

今回の話題と関連して,「#3180. 徐々に高頻度語の仲間入りを果たしてきたフランス・ラテン借用語」 ([2018-01-10-1]),「#2667. Chaucer の用いた語彙の10--15%がフランス借用語」 ([2016-08-15-1]),「#2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率」 ([2015-07-28-1]) なども参照されたい.

2020-08-24 Mon

■ #4137. 中世イングランドで話されていたフランス語は Anglo-Norman か Anglo-French か [oed][anglo-norman][french][me][variety]

中世イングランドで用いられていたフランス語変種を何と呼ぶべきかという問題には,私も長らく頭を悩ませてきた.英語史でも,かの変種についてしばしば言及する機会があるからだ.本ブログの記事に付しているタグとしては専ら (anglo-norman) を用いてきたが,記事本文中では Anglo-French の呼称も自由に使ってきた.

先日の記事「#4133. OED による英語史概説」 ([2020-08-20-1]) で紹介した記事の1つ Middle English: an overview を読んでいたところ,"A multilingual context" と題する節のもとで標記の問題への言及を見つけた.

What to call the French used in Britain in this period is a difficult scholarly question. Traditionally the term 'Anglo-Norman' has been used, notably in the title of The Anglo-Norman Dictionary. In fact, the present-day editors of that dictionary note that in many ways 'Anglo-French' is a more appropriate term, since it better reflects the wide variety of inputs shown by the French used in medieval Britain. OED3 retains the term 'Anglo-Norman' largely to maintain consistency with the title of The Anglo-Norman Dictionary.

引用の通り,OED の方針としては既存の The Anglo-Norman Dictionary の呼称と一致させて Anglo-Norman を用いるということのようだ.しかし,内心のところ,問題の変種へのインプットは Norman French に限られないことから,もっと広めに Anglo-French と呼ぶ方が適切だろうとは考えているらしい.

直接 OED の当該の語に当たってみよう.まず Anglo-Norman は "The variety of the French language spoken and written in medieval England after the Norman Conquest." とある.言語名の名詞としては1818年,形容詞としては早く1735年に初出しているが,あくまで近代になってからの呼称である.

一方,Anglo-French に当たってみると,"The variety of the French language spoken and written in medieval England." とある.ほとんと違いがない.言語名の名詞としては1862年,形容詞として1884年に初出している.しかし,その定義のすぐ下に,次の重要な注があった.

Anglo-French developed after the Norman Conquest of 1066, and remained current in some functions until the mid 15th cent. The term 'Anglo-Norman' has traditionally been used in the same meaning (cf. Anglo-Norman n. 2), but 'Anglo-French' is preferred by many scholars since this variety was not solely based on Norman French. French in later legal use is normally distinguished as Law French (see law-French n. at law n.1 Compounds 3).

やはり OED も内心は Anglo-French の呼び名のほうを買っているように思われる.Law French という別の視点からのくくりも意識しておきたい (cf. law_french) .言語名を巡る問題は,それだけで歴史社会言語学的な難問となることが多い.「#3558. 言語と言語名の記号論」 ([2019-01-23-1]) も参照されたい.

2020-08-20 Thu

■ #4133. OED による英語史概説 [oed][lexicology][lexicography][historiography][toc][hel][hel_education]

OED のサイトには当然ながら英語史に関する情報が満載である.じっくりと読んだことはなかったのだが,掘れば掘るほど出てくる英語史のコンテンツの宝庫だ.OED が運営しているブログがあり,そこから英語史概説というべき記事を以下に挙げておきたい.

OED らしく語彙史が中心となっているのはもちろん,辞書編纂の関心が存分に反映されたユニークな英語史となっており,実に読み応えがある.とりわけ古い時代の英語の evidence や manuscript dating の問題に関する議論などは秀逸というほかない(例えば Middle English: an overview の "Our surviving documents" などを参照).また,終着点となる20世紀の英語の評論などは,今後の英語を考える上で必読ではないか.

是非,以下をじっくり読んでもらえればと思います.

・ Old English --- an overview

- Historical background

- Some distinguishing features of Old English

- The beginning of Old English

- The end of Old English

- Old English dialects

- Old English verbs

- Derivational relationships and sound changes

- cf. Old English in the OED

・ Middle English: an overview

- Historical period

- The most important linguistic developments

- A multilingual context

- Borrowing from early Scandinavian

- Borrowing from Latin and/or French

- Pronunciation

- A period characterized by variation

- Our surviving documents

・ Early modern English --- an overview

- Boundaries of time and place

- Variations in English

- Attitudes to English

- Vocabulary expansion

- 'Inkhorn' versus purism

- Archaism and rhetoric

- Regulation and spelling reform

- Fresh perspectives: Old English and new science

・ Nineteenth century English: an overview

- Communications and contact

- Local and global English

- Recording the language

- A changing language: grammar and new words

- The science of language

・ Twentieth century English: an overview

- Circles of English

- Convergence: the birth of cool

- Restrictions on language

- Lexis: dreadnought and PEP talk

- Modern English usages

2020-08-18 Tue

■ #4131. イギリスの世界帝国化の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes" [oed][map][lexicology][lexicography][philology][history][web_service]

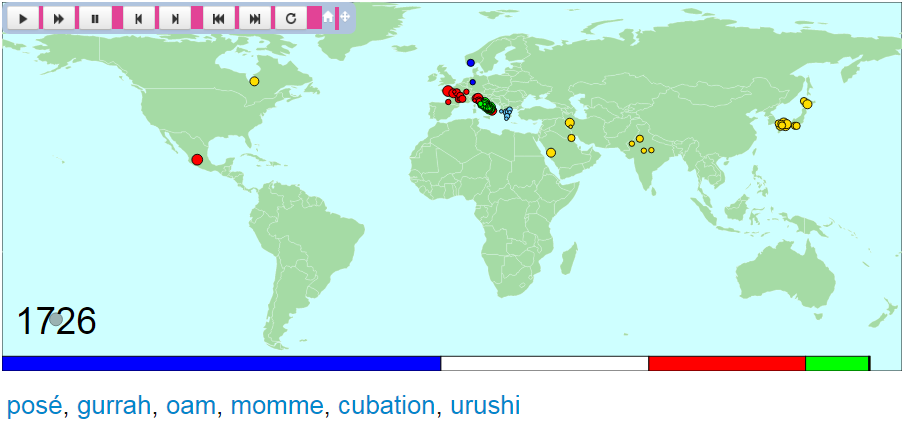

昨日の記事「#4130. 英語語彙の多様化と拡大の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes"」 ([2020-08-17-1]) で紹介した同じコンテンツを,異なる角度から改めて眺めてみたい.The OED in two minutes で公開されている英語語彙史地図のコンテンツである.

中英語の始まりとなる1150年から再生して1年ごとに時間を進めていくと,しばらくは動きがヨーロッパ内部に限られており,さしておもしろくもないのだが,15世紀後半になってくると中東や北アフリカなどに散発的に点が現われてくる.そして,16世紀後半になると新大陸やインド方面にも点がポツポツしてきて,日本も舞台に登場してくる.この状況は17,18世紀にかけて稀ではなくなってくる.次に注目すべき動きが出てくるのは,18世紀後半のオセアニア,太平洋,南アフリカといった南半球を中心とした海洋地域である.19世紀に入るとアフリカや東南アジアを含めた世界の広域に点が打たれるようになり,同世紀後半には南アメリカも加わる.20世紀はまさにグローバルである.

実におもしろい.同時に,実に恐ろしい.16世紀後半から19世紀終わりまでの時間枠に関するかぎり,そのままイギリスの世界帝国化の足跡を語彙史の観点からパラフレーズしたコンテンツに見えてきたからだ.直接・間接にイギリスの支配権の及ぶ領土を塗りつぶした世界史の地図は「軍事的な」地図として見慣れているし,ある意味で分かりやすい.しかし,今回のような「語彙史的な」地図がそれと多かれ少なかれ一致するというのは,何とも薄気味悪い.そして,後者の地図が,OED という英語文献学の粋というべき学術的な成果物を利用して作成されていること,またその辞書それ自身が大英帝国の最盛期である19世紀半ばの企画の産物であることを思い出すとき,薄気味悪さ以上に,得体のしれない恐ろしさを感じる.

OED は学術的(文献学的)偉業を体現するツールであり,その点で私も賞賛を抑えることができない.しかし,その事実を認めつつ,それ自体が,毀誉褒貶相半ばする近代世界史の産物であることは肝に銘じておきたい.関連して以下の記事も参照.

・ 「#3020. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (1)」 ([2017-08-03-1])

・ 「#3021. 帝国主義の申し子としての比較言語学 (2)」 ([2017-08-04-1])

・ 「#3376. 帝国主義の申し子としての英語文献学」 ([2018-07-25-1])

・ 「#3603. 帝国主義,水族館,辞書」 ([2019-03-09-1])

・ 「#3767. 日本の帝国主義,アイヌ,拓殖博覧会」 ([2019-08-20-1])

2020-08-17 Mon

■ #4130. 英語語彙の多様化と拡大の歴史を視覚化した "The OED in two minutes" [oed][map][lexicology][borrowing][lexicography][philology][statistics][web_service][hel_education]

The OED in two minutes に,中英語の始まる1150年から2010年までの英語(借用)語彙史を地図上で視覚化してダイジェストで示すコンテンツが公表されている.これは凄いコンテンツ.実にみごとに英語語彙の多様化と拡大の歴史が表現されており,しかもいろいろな意味で考えさせられる.こちらからどうぞ.

地図の下にある色付きの帯は,現代英語における語種ごとの総トークン頻度を表わしている(背後で利用されているデータベースは Google Ngrams の1970--2008年の部分だという).試しに2010年現在の地図に示される統計をみてみると,総トークン頻度にして,ゲルマン系の語彙(青帯)が49%,英語要素に基づく複合語など(白帯)が26%なので,ここまでで全体の3/4である.ロマンス系の語彙(赤帯)が18%,ラテン語が7%,そしてその他が0.2%だ.英語史では語彙の歴史は借用の歴史であるというのが定番だが,トークン頻度で考える限り,現在でも英語の語彙は圧倒的にアングロサクソン(あるいはゲルマン)的であるといってよいことになる.この事実については「#3400. 英語の中核語彙に借用語がどれだけ入り込んでいるか?」 ([2018-08-18-1]) と,そこに張ったリンク先の記事を参照.

地図左下の年号に重なって描かれている灰色のバブルは,高頻度かつ多数の単語が加わった年ほど大きくなり,低頻度かつ少数の単語が加わったにすぎない年には小さくなる.17世紀を通じて相対的に大きかったバブルが,18世紀にかけてしぼんでいく様子も興味深い (cf. 「#2995. Augustan Age の語彙的保守性」 ([2017-07-09-1]),「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1]),「#4070. 18世紀の語彙的低迷のなぞ」 ([2020-06-18-1])) .

英語(語彙)史を大づかみするには,このようなダイジェストの視覚コンテンツが威力を発揮する.

2020-08-16 Sun

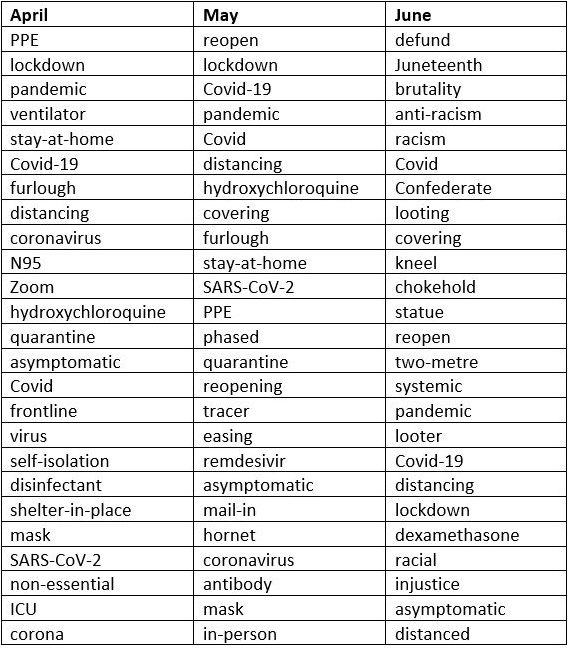

■ #4129. 「コロナ禍と英語」ならこれしかないでしょ! --- OED の記事より [oed][neologism][zipfs_law][covid]

OED が発信するコロナ関連語録の記事をいくつか読んだ.特集というよりは論文といってよい質の高さである.いずれにせよこれほどショッキングかつリアルタイムの社会言語学的論考は,あまり見たことがない.読んでいると苦しくなるかもしれないので要注意.以下,いくつか主要な記事をピックップする.

(1) New words list July 2020: この7月の新語(義)の一覧.

(2) Social change and linguistic change: the language of Covid-19: 目下のコロナ禍のみならず歴史的な疫病(14,17世紀ヨーロッパの惨禍を含む)に由来する語彙の歴史的解説もすばらしい.取り上げられている単語を列挙すると,Covid-19, WFH, elf-isolation, self-isolating, infodemic, shelter-in-place, social distancing, elbow bump, WFH, PPE, personal protective equipment, pestilence, pest, pox, pock, smallpox, epidemic, Black Plague, Black Death, self-quarantined, yellow fever, Spanish influenza, Spanish flu, poliomyelitis, polio, AIDS, SARS, coronaviruses となる.

(3) July 2020 update: scientific terminology of Covid-19: とりわけコロナ関連の医学的・科学的な用語が紹介されている.科学的事実が明らかになるにつれ語の定義も変わってくるという,まさに現在進行形の話題である.新型コロナウィルスを意味する語も Covid, C-19, CV-19, CV, corona など様々にあること,そして目下もう1つの省略語 rona がアメリカ英語やオーストラリア英語でトレンドになってきてことが取り上げられている (cf. 「#1102. Zipf's law と語の新陳代謝」 ([2012-05-03-1])) .なお,Covid-19, n. 自体の定義も最近書き換えられたようだ.

(4) Using corpora to track the language of Covid-19: update 2: コーパスを用いた,今年の4月から6月にかけてのトレンドワードの調査が紹介されている.トレンドワードのリストは,まさにその時代を映し出していることがよく分かる.これほど切実な生の単語リストを,私は見たことがない.社会と言語の驚くべき関係を見せつけられた感がする.

イギリス英語では Covid-19 の綴字が,アメリカ英語では COVID-19 の綴字が多いという結果も興味深い.6月のリストには,コロナ関連に紛れて "Black Lives Matter" に関する racism, injustice, police brutality, defund, Confederate statues なども現われる.いろいろな意味でため息が出てしまうリストである.

2020-08-14 Fri

■ #4127. spirit にみる OED3 の改訂作業 [oed][wycliffe][bible][lexicography][polysemy]

本ブログで,去る6月の前半に「#4060. なぜ「精神」を意味する spirit が「蒸留酒」をも意味するのか?」 ([2020-06-08-1]),「#4061. sprite か spright か」 ([2020-06-09-1]),「#4062. ラテン語 spirare (息をする)の語根ネットワーク」 ([2020-06-10-1]) の記事を公開したが,奇しくもその数日後に OED3 編集者の手による spirit の項目に関するブログ記事 That's the spirit: revising 'spirit', n. for OED3 がアップされていた.

spirit は,得体の知れない超自然的な指示対象をもち,多義であり,文化史上も重要で,かつ使用頻度も高い単語なので,OED のなかでも大きめのエントリーとなっている.編集者としては,このような多義語に関して語義の順序をいかにするかというのが問題となる.とりわけこの単語の場合には,当初より多義語として英語に借用されたために,英語史の枠内にとどまっている限り,複数の語義を時間順に整理するということがあまり意味をなさないのだ.実際,様々な語義が,14世紀末の Wycliffe の英訳聖書において初出している.「歴史的原則」を謳う OED のポリシーとして,多義を通時的に関係づけたいのはやまやまだが,さすがに OED もそれ以前のフランス語史やラテン語史にまで深く踏み込むことはしないので,語義の順序問題はかなり悩ましかったようだ.それでも種々の例文を解釈しなおして語義区分を改めたり,なるべく論理的な順序を目指して試行錯誤するなど,涙ぐましい編集努力の様子が,その記事に綴られている.

ほかに,従来版では spirit の項のもとで扱われていた Holy Spirit が,改訂版では独立の見出し語として立てられたという.これも文化史的な意義において重要な改編というべきだろう.

OED 改訂の舞台裏を覗き見したかのような,また philology の素養のある編集者の職人技を目の当たりにしたかのような読後感の記事だった.OED 改訂の苦難,ひいては辞書編纂にまつわる苦労がよく分かる記事である.お薦め.

2020-08-11 Tue

■ #4124. OMG = "oh my God" は100年の歴史を誇る [abbreviation][shortening][net_speak][initialism][oed]

ネット上の書き言葉では,ASAP = "as soon as possible" や CUL8R = "see you later" などのアルファベット頭字語 (initialism) と呼ばれる独特な省略記法が頻用される.「#817. Netspeak における省略表現」 ([2011-07-23-1]) で様々な例を示したが,これらは「#625. 現代英語の文法変化に見られる傾向」 ([2011-01-12-1]) や「#860. 現代英語の変化と変異の一覧」 ([2011-09-04-1]) で触れたように,すぐれて現代的な言語変化の傾向を反映するものとして注目されている.

一方,このようなアルファベット頭字語そのものは実は古代から存在しており,発想そのものが新しいわけではないことにも注意すべきである.これについては「#3935. アルファベット頭字語の浮き沈みの歴史」 ([2020-02-04-1]) で見たとおりだ.

標題の OMG = "oh my God" も,一見すると近年のネット上の新記法かと思われるかもしれないが,OED によると初例はなんと1917年のことである.

Quot. 1917 is perhaps with punning reference to the Order of St. Michael and St. George, which at this point had had no Grand Master or Chancellor for several years: these were appointed on 4 Oct. 1917.

1917 J. A. F. Fisher Let. 9 Sept. in Memories (1919) v. 78 I hear that a new order of Knighthood is on the tapis---O.M.G. (Oh! My God!)---Shower it on the Admiralty!!

その次に挙げられている例は飛んで1994年のものであり,現在の本格的な使用の発端が Netspeak にあることは間違いなさそうだが,(この例では古代からとは言えないものの)100年ほどの歴史を誇っているとは言えるだろう.

このアルファベット頭字語については,目下 OED のこちらのページで特集グラフィック・コンテンツとして取り上げられている.非常におもしろいコンテンツなので,ぜひどうぞ.上記の1917年の初例が,かの Winston Churchill に宛てられた手紙での使用例だったとは!

2020-08-09 Sun

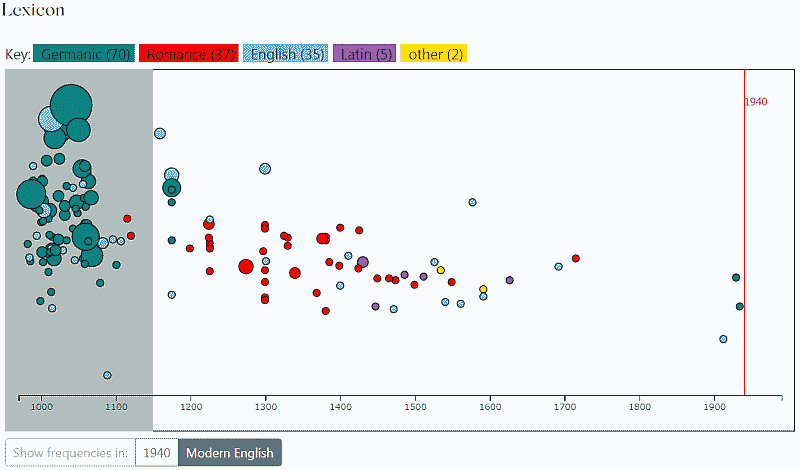

■ #4122. 物凄いツールが現われた --- OED Text Visualizer (beta) [web_service][oed][etymology]

OED が OED Text Visualizer という物凄いツールを作っている.入力欄に英文テキストを放り投げると,OED の情報に基づいて背後で各単語にタグが付され,初出年代と語源をタイムラインで視覚的に表現してくれるというものだ.いつかこのようなツールが作れたら(あるいは誰かが作ってくれたら)いいなと私が夢見ていたような語源表示ツールである.これまでも技術的には十分に可能だったろうが,本格的に取り組む者が現われなかった.それを OED が実装してくれたというのは,さすがである.開発中のベータ版ということで,入力する英文は500語まで,また1750年以後の英文でないと精度が下がるなどの制限はあるようだが,十分に楽しめる.

百聞は一見に如かず.「#3276. Churchill の We Shall Fight on the Beaches 演説」 ([2018-04-16-1]) より,308語からなる英文の1節を放り込んでみた.1940年の演説なので,その年代も添えつつ Vizualize ボタンをクリックすると,次のような図が返される(画像クリックで拡大).

テキストに現われる各単語(レンマ)がバブルで表現されている.バブルの左右の位置はその語の初出年代に対応し,色は語源に,大きさは同テキスト内の頻度に対応する.バブルにマウスを乗せれば,その語の詳しい情報が得られる.スゴい.

画面のさらに下には,各単語が token ベース,および lexeme ベースでタグ付けされた情報が一覧され,CSV や JSON でダウンロードできるので,後からプログラムを用いて詳しく分析することも可能である.

いや,驚いた.英語史の研究方法もどんどん変わっていきそうだ.

2020-07-23 Thu

■ #4105. 銅像破壊・撤去,新PC,博物館 [political_correctness][hel_education][oed][taboo]

BLM 運動が,世界で雪崩をうったように拡がっている.英米などでは,黒人差別への抗議のジェスチャーとして,奴隷制に関わる歴史的(英雄的)人物の銅像を破壊・撤去する動きが繰り広げられている.平行的に,言葉の問題への波及も見逃せない.7月13日のウェブ上の記事「IT用語も『奴隷』廃止の動き 『slave』は『フォロワー』や『レプリカ』にを読んで,おっと思った.master, slave, whitelist, blacklist などの表現が不適切であるとして,IT業界において leader, follower, allowlist, denylist 等の別の表現に置換される動きが起こってきているという.

銅像破壊・撤去と,この「新しいPC」 (political_correctness) というべき2つの現象は,とてもよく似ている.まず,社会の潮流により,既存の伝統的な表現形式が,部分的に自主的に取り下げられているという点が共通している.

もう1つの共通点は,もとの表現形式が取り下げられたことにより,確かに一見すると問題はなくなったようにみえるが,決して問題が解決されたわけではないということだ.ネガティブにいえば,そのモノが見えなくなることでかえって何が問題だったのかが思い出せなくなるわけであり,時間をかけて意識的な問題解決が試みられなかっただけに,いつか容易に再燃する可能性もあるという点だ.

一方,銅像破壊・撤去と「新しいPC」には簡単に比較できない点もある.銅像はいったん取り下げられば,確かに人々が目にする機会はなくなる.しかし,master や slave という表現は,IT用語としては控えられるようになるかもしれないが,別の(本来の)語義としては現役であり,今まで通り人々の口にものぼるし耳にも入ってくる.換言すれば,銅像は視界から消えればその意義(歴史的英雄性)も同様に見えなくなる(ように思われる)が,言葉はすぐに完全に消えることはなく,別の語義としてではあれ,相変わらず用いられ続けるということだ.むしろ,言葉自体は根強く生き残ることが多い(cf. 「#1338. タブーの逆説」 ([2012-12-25-1])).

目下の銅像破壊・撤去に関して,その銅像を博物館に保管・展示することで教育・研究の素材として活かすべきだと論じている識者もいる.これは良案だと思う.

では,言葉についてはどうだろうか.IT用語における master と slave の置換については,別の表現に置換して「ハイ終わり」では,やはり満足できない.銅像を博物館に保管・展示するのと同様に,言葉の博物館が欲しい.それは,英語の場合でいえば OED のような歴史的原則に基づいた辞書に「差別的」語義を記録しておくことだろう.私は OED は専門的には奇跡的なレベルの辞書だと思っているが,それでもやはり物理的存在感のある博物館とは異なり,一般的にいえば存在感が薄い.英語に限らずだが,もっと物理的な存在感のある「言葉の博物館」が本当にあるとよいなと常々思っている.

2020-07-09 Thu

■ #4091. DOST と SND --- スコットランド英語版の OED [scots_english][oed][dictionary][lexicography][lexicology][world_englishes][laos]

世界の諸英語 (world_englishes) の種類は数あれど,スコットランド英語 (scots_english) は英語史において特別な位置づけにある.というのは,イングランド英語を除けば,スコットランド英語は,直接的に古英語に由来する唯一の英語変種だからである.一般的にはイギリスで話される英語の(訛った)1変種にすぎないという見方が普通だろうが,歴史的にみればイングランド英語と並んで最長の連続性を誇る由緒正しい変種なのである.その略史については「#1719. Scotland における英語の歴史」 ([2014-01-10-1]) を参照されたい.

この由緒正しい Scots English については,OED に匹敵する堂々たる歴史的な辞書が編纂されている.2つ紹介しよう.1つめは,DOST こと Craigie et al. 編の A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue である.カバーする時代は,スコットランド英語がイングランド英語とは異なる独立した変種として発展した中世後期から,独立性を失っていった1700年頃までである.ただし,情報収集方針は時代によって異なっており,1600年までは包括的に収録されているといってよいが,17世紀分についてはスコットランドに特化した地域変種の辞書となっている.

また,編纂方針について変遷が重ねられてきたという事情もある.編纂の前半期には,同一の語源に遡るものでも語形が異なる場合には,異なる見出しを立てるという方針が採られていたが,R の項に差し掛かってからは新編集長の Dareau のもとで to と till を同じ見出しのなかで扱うなど異なる方針が採られることになった.背景には,編纂作業に関わる時間やリソースの逼迫があったようだ.

一方,1700年以降のスコットランド英語を担当しているのが,もう1つの辞書,SND こと Scottish National Dictionary である.こちらも歴史的原則に立って編纂されているが,スコットランド英語がすでに独立性をほぼ失っていた時代を対象としていることもあり,1地域変種辞書というべき位置づけとなっている.

この DOST と SND を合わせて,スコットランド英語版の OED とみなしてよいだろう.実際,両者は Dictionary of the Scots Language の名のもとに統合され,オンラインでアクセスできるようになっている.

ちなみに,LALME や LAEME に対応する,古いスコットランド英語についての方言地図も作成されており A Linguistic Atlas of Older Scots (LAOS) としてこちらからアクセスできる.

以上,Durkin (1152--53) を参照して執筆した.

・ Craigie, William A., Adam Jack Aitken, James A. C. Stevenson, and Marace Dareau, eds. A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue. Oxford: OUP, 1931--2002. Available online as part of Dictionary of the Scots Language at https://dsl.ac.uk/ .

・ Grant, William and David D. Murison, eds. The Scottish national Dictionary: Designed Partly on Regional lines and Partly on Historical Principles, and Containing All the Scottish Words Known to be in Use or to have been in Use Since c. 1700. Edinburgh: Scottish National Dictionary Association, 1931--76. Supplement 2005. Available online as part of Dictionary of the Scots Language at https://dsl.ac.uk/ .

・ Williamson, Keith. A Linguistic Atlas of Older Scots, Phase 1: 1380--1500 (LAOS). 2007. Available online at http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/laos1/laos1.html .

・ Durkin, Philip. "Resources: Lexicographic Resources." Chapter 73 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 1149--63.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow