2015-07-28 Tue

■ #2283. Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙の残存率 [shakespeare][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

初期近代英語期のラテン語やギリシア語からの語彙借用は,現代から振り返ってみると,ある種の実験だった.「#45. 英語語彙にまつわる数値」 ([2009-06-12-1]) で見た通り,16世紀に限っても13000語ほどが借用され,その半分以上の約7000語がラテン語からである.この時期の語彙借用については,以下の記事やインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) に関連するその他の記事でも再三取り上げてきた.

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1])

・ 「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1])

・ 「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1])

16世紀後半を代表する劇作家といえば Shakespeare だが,Shakespeare の語彙借用は,上記の初期近代英語期の語彙借用の全体的な事情に照らしてどのように位置づけられるだろうか.Crystal (63) は,Shakespeare において初出する語彙について,次のように述べている.

LEXICAL FIRSTS

・ There are many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have survived into Modern English. Some examples:

accommodation, assassination, barefaced, countless, courtship, dislocate, dwindle, eventful, fancy-free, lack-lustre, laughable, premeditated, submerged

・ There are also many words first recorded in Shakespeare which have not survived. About a third of all his Latinate neologisms fall into this category. Some examples:

abruption, appertainments, cadent, exsufflicate, persistive, protractive, questrist, soilure, tortive, ungenitured, unplausive, vastidity

特に上の引用の第2項が注目に値する.Shakespeare の初出ラテン借用語彙に関して,その3分の1が現代英語へ受け継がれなかったという事実が指摘されている.[2010-08-18-1]の記事で触れたように,この時期のラテン借用語彙の半分ほどしか後世に伝わらなかったということが一方で言われているので,対応する Shakespeare のラテン語借用語彙が3分の2の確率で残存したということであれば,Shakespeare は時代の平均値よりも高く現代語彙に貢献していることになる.

しかし,この Shakespeare に関する残存率の相対的な高さは,いったい何を意味するのだろうか.それは,Shakespeare の語彙選択眼について何かを示唆するものなのか.あるいは,時代の平均値との差は,誤差の範囲内なのだろうか.ここには語彙の数え方という方法論上の問題も関わってくるだろうし,作家別,作品別の統計値などと比較する必要もあるだろう.このような統計値は興味深いが,それが何を意味するか慎重に評価しなければならない.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

2015-03-14 Sat

■ #2147. 中英語期のフランス借用語批判 [purism][loan_word][french][inkhorn_term][me][lexicology]

16世紀には,ラテン借用語をはじめとしてロマンス諸語などからの借用語がおびただしく英語へ流入した(「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1]) や「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1]) を参照).日本語でも明治以降,大量の漢語が作られ,昭和以降は無数のカタカナ語が流入した(「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1]) 及び「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1]) を参照).これらの時代の各々において,純粋主義 (purism) の立場からの借用語批判が聞かれた.借用語をむやみやたらに使用するのは控えて,本来語をもっと多く使うべし,という議論である.

英語史においてあまり聞かないのは,中英語期に怒濤のように押し寄せたフランス借用語に対する批判である.「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) で見たとおり,英語はノルマン・コンクェスト後の数世紀間で,歴史上初めて数千語という規模での大量語彙借用を経験してきたが,そのフランス借用語への批判はなかったのだろうか.

確かにルネサンス期のインク壺語批判ほどは目立たないが,中英語におけるフランス借用語批判がまったくなかったわけではない.Ranulph Higden (c. 1280--1364) によるラテン語の Polychronicon を1387年に英訳した John of Trevisa (1326--1402) は,ある一節で,古ノルド語とともにフランス語からの借用語の無分別な使用について苦情を呈している.Crystal (186) からの引用を再現しよう.

by commyxstion and mellyng, furst wiþ Danes and afterward wiþ Normans, in menye þe contray longage ys apeyred, and som vseþ strange wlaffyng, chyteryng, harryng, and garryng grisbittyng.

同様に,Richard Rolle of Hampole (1290?--1349.) による Psalter (a1350) でも,"seke no strange Inglis" (見知らぬ英語は使わない)とフランス借用語に対して暗に不快感を示しているし,15世紀に Polychronicon を英訳した Osbern Bokenham (1393?--1447?) も,フランス語が英語を野蛮にしたと非難している (Crystal 186) .しかし,彼らとて,自らの著書のなかで,洗練されたフランス借用語を用いていたことはいうまでもない.

このように中英語期のフランス借用語への純粋主義的な非難はいくつか確認されるが,後世の激しいインク壺語批判に比べれば単発的であり,特に大きな潮流を形成しなかったようだ.英語自体がまだ一国の言語としておぼつかない地位にあって,英語の本来語への思慕や借用語の嫌悪という純粋主義的な態度が世の注目を浴びるには,まだ時代が早かったものと思われる.それでも,この中英語期の早熟な純粋主義的批判は,後世の苛烈な批判の前段階として,確かに英語史上に位置づけられるものではあるだろう.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2014-10-17 Fri

■ #1999. Chuo Online の記事「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」 [japanese][katakana][kanji][lexicology][lexicography][inkhorn_term][loan_word][waseieigo][link]

ヨミウリ・オンライン(読売新聞)内に,中央大学が発信するニュースサイト Chuo Online がある.そのなかの 教育×Chuo Online へ寄稿した「カタカナ語の氾濫問題を立体的に視る」と題する私の記事が,昨日(2014年10月16日)付で公開されたので,関心のある方はご参照ください.ちょうど今期の英語史概説の授業で,この問題の英語版ともいえる初期近代英語期のインク壺語 (inkhorn_term) を巡る論争について取り上げる矢先だったので,とてもタイムリー.数週間後に記事の英語版も公開される予定. *

上の投稿記事に関連する内容は本ブログでも何度か取り上げてきたものなので,関係する外部リンクと合わせて,この機会にリンクを張っておきたい.

・ 文化庁による平成25年度「国語に関する世論調査」

・ 「#32. 古英語期に借用されたラテン語」 ([2009-05-30-1])

・ 「#296. 外来宗教が英語と日本語に与えた言語的影響」 ([2010-02-17-1])

・ 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1])

・ 「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1])

・ 「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1])

・ 「#845. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合」 ([2011-08-20-1])

・ 「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」 ([2012-03-29-1])

・ 「#1202. 現代英語の語彙の起源と割合 (2)」 ([2012-08-11-1])

・ 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])

・ 「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」 ([2013-03-07-1])

・ 「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」 ([2013-03-08-1])

・ 「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1])

・ 「#1526. 英語と日本語の語彙史対照表」 ([2013-07-01-1])

・ 「#1606. 英語言語帝国主義,言語差別,英語覇権」 ([2013-09-19-1])

・ 「#1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-28-1])

・ 「#1616. カタカナ語を統合する試み,2種」 ([2013-09-29-1])

・ 「#1617. 日本語における外来語の氾濫」 ([2013-09-30-1])

・ 「#1624. 和製英語の一覧」 ([2013-10-07-1])

・ 「#1629. 和製漢語」 ([2013-10-12-1])

・ 「#1630. インク壺語,カタカナ語,チンプン漢語」 ([2013-10-13-1])

・ 「#1645. 現代日本語の語種分布」 ([2013-10-28-1]) とそこに張ったリンク集

・ 「#1869. 日本語における仏教語彙」 ([2014-06-09-1])

・ 「#1896. 日本語に入った西洋語」 ([2014-07-06-1])

・ 「#1927. 英製仏語」 ([2014-08-06-1])

(後記 2014/10/30(Thu):英語版の記事はこちら. *)

2013-09-28 Sat

■ #1615. インク壺語を統合する試み,2種 [binomial][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicography][lexicology]

バケ『英語の語彙』 (87--88) によれば,16世紀を中心に大量にラテン語から借用された inkhorn_term などの学者語は,普及に際して主として2つの手段があった.1つは,Mulcaster の提案に端を発する Cawdrey, Bullokar, Cockeram などの初期の難語辞書の出版である.「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]) および「#609. 難語辞書の17世紀」 ([2010-12-27-1]) の記事でみたように,17世紀は難語辞書の世紀といってよい.インク壺語を是とする識者たちは,これらの辞書によって,人々を啓蒙しようとしたのである.

もう1つは,文章のなかで簡易説明を加えながら実際に使ってゆくという方法である.これはすでに Chaucer や Caxton などにより伝統的に用いられてきた方法だが ([2011-07-26-1]の記事「#820. 英仏同義語の並列」を参照),近代でも改めて利用されることとなった.例えば,Sir Thomas Elyot (1490?--1546) は,(1) "circumspectin…which signifieth as moche as beholding on every parte" のように簡単な定義を施す, (2) "difficile or harde", "education or bringing up of children", "animate or give courage" のようにor による並置を用いる, (3) "gross and ponderous", "agility and nimbleness" のように and による並置を用いる,などの方法に訴えた.その後,16世紀の終わりに Francis Bacon (1561--1626) が,Essays のなかで,教育上の目的によりしばしばこれを用いた.詩人などの文学者もまた,韻律上の動機づけ,または強調や威厳などの文体的な目的により,この方法を多用した.Shakespeare の "by leave and by permission", "dispersed and scattered", "the head and source",あるいは The Book of Common Prayer における "I pray and beseech you, that we have erred and strayed" のごとくである.これらはときに虚飾主義に陥り,書きことばと話しことばの乖離を促すことになった(法律語からの例については,[2013-04-09-1]の記事「#1443. 法律英語における同義語の並列」を参照).しかし,上記の方策は,初期近代英語期のおびただしい借用語の流入に対する語彙統合の努力でもあったのだ.

なお,(2), (3) の等位接続詞による並置という方法は,(1) の難語辞書内でも当然多用された.「#1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化」 ([2013-09-22-1]) の検索式の例文として「定義に " or " を含むもの」と「定義に " and " を含むもの」を挙げておいたのは,そのためである.

関連して,and で並置する2項イディオム (binomial idiom) の他の話題も参照.

・ ポール・バケ 著,森本 英夫・大泉 昭夫 訳 『英語の語彙』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1976年.

2013-09-22 Sun

■ #1609. Cawdrey の辞書をデータベース化 [cawdrey][lexicography][dictionary][cgi][web_service][inkhorn_term][lexicology]

英語史上初の英英辞書 Robert Cawdrey の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) について,cawdrey の各記事で話題にしてきた.オンライン版をもとに,語彙項目記述を検索可能とするために,簡易データベースをこしらえた.半ば自動でテキストを拾ってきたものなので細部にエラーがあるかもしれないが,とりあえず使えるようにした.

データベースの内容をブラウザ上でテキスト形式にて閲覧したい方は,こちらをどうぞ(あるいはテキストファイルそのものはこちら).

以下,使用法の説明.SQL対応で,テーブル名は "cawdrey" として固定.select 文のみ有効.フィールドは7項目で,ID (整理番号),LEMMA (登録語),INITIAL (登録後の頭文字1文字),LENGTH (登録後の文字数),LANGUAGE (借用元言語),DEFINITION (定義語句),DEF_WC (定義語句の語数).典型的な検索式を例として挙げておこう.

# データベース全体を表示

select * from cawdrey

# 登録語をイニシャルにしたがってカウント

select INITIAL, count(*) from cawdrey group by INITIAL

# 登録語を文字数にしたがってカウント

select LENGTH, count(*) from cawdrey group by LENGTH

# 登録語を語源にしたがってカウント

select LANGUAGE, count(*) from cawdrey group by LANGUAGE

# 語源と語の長さの関係

select LANGUAGE, avg(LENGTH) from cawdrey group by LANGUAGE

# 登録語を定義語数にしたがってカウント

select DEF_WC, count(*) from cawdrey group by DEF_WC

# 語源と定義語数の関係

select LANGUAGE, avg(DEF_WC) from cawdrey group by LANGUAGE

# 定義に "(k)" (kind of) を含むもの

select LEMMA, DEFINITION from cawdrey where DEFINITION like '%(k)%'

# 定義に " or " を含むもの

select LEMMA, DEFINITION from cawdrey where DEFINITION like '% or %'

# 定義に " and " を含むもの

select LEMMA, DEFINITION from cawdrey where DEFINITION like '% and %'

# 定義がどんな句読点で終わっているか集計

select substr(DEFINITION, -1, 1), count(*) from cawdrey group by substr(DEFINITION, -1, 1)

・ ポール・バケ 著,森本 英夫・大泉 昭夫 訳 『英語の語彙』 白水社〈文庫クセジュ〉,1976年.

2013-07-20 Sat

■ #1545. "lexical cleansing" [sociolinguistics][lexicology][purism][language_planning][inkhorn_term]

標題は "ethnic cleansing" を想起させる不穏な用語である.ある言語から借用語を一掃しようとする純粋主義の運動であり,ときに政治性を帯び,言語政策として過激に遂行されることがある.日本語でも横文字の過剰な使用をいぶかる向きはあるし,英語でもかつてルネサンス期にインク壺語 (inkhorn_term や "oversea language" ([2013-03-08-1]の記事「#1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language"」を参照)に対抗して本来語へ回帰しようとする純粋主義が現われた([2013-03-07-1]の記事「#1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰」を参照).しかし,日本語でも英語でも,体系的に借用語を一掃し,本来語へ置き換えるような社会運動へと発展したことはなかった.

ところが,トルコでは lexical cleansing が起こった.そして,現在も進行中である.カルヴェ (96--100) に,トルコにおける「言語革命」が紹介されている.第1次世界大戦後のトルコの祖国解放運動の指導者にしてトルコ共和国の初代大統領となった Mustafa Kemal Atatürk (1881--1938) は,共和国の創設 (1923) に伴い,トルコ文語の改革を断行した.まず,Kemal は,オスマン帝国の痕跡を排除すべくアラビア文字からローマ字への切り替えを断行した.続けて,当時のトルコ文語がアラビア語やペルシア語の語彙要素を多分に含む学者語となっていたことから,語彙の体系的なトルコ語化を画策した.

アラビア語やペルシア語の語彙要素を浄化すべくトルコ新体制が最初に行なったことは,トルコ語研究学会に,広い意味でのトルコ語の語彙集を作成させるということだった.広い意味でのトルコ語とは,チュルク諸語族に属する新旧のあらゆる言語を念頭においており,オルホン銘碑の言語,トルキスタン,コーカサス,ヴォルガ,シベリアで話される現代語,ウイグル語やチャガタイ語,アナトリア語やバルカン語諸方言を含んでいた.古語を掘り起こし,本来語要素を複合し,目的のためには時に語源を強引に解釈したりもした.おもしろいことに,ヨーロッパ語からの借用は,アラビア・ペルシア要素の排除という大義のもとに正当化されることがあった.トルコ新体制は,強い意志と強権の発動により,lexical cleansing を行ない,純正トルコ語を作り出そうとしたのである.

トルコのほかに,類例として Serbo-Croatian における語彙浄化が挙げられる.1990年代前半の旧ユーゴ解体に伴い,それまで Serbo-Croatian と呼ばれていた言語が,民族・文化・宗教という分裂線により Serbian と Croatian という異なる言語へ分かれた.以降,互いの言語を想起させる語彙を公的な場から排除するという lexical cleansing の政策がとられている.なお,北朝鮮でも,中国語の語彙と文字を排除する純血運動が主導されている.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ(著),西山 教行(訳) 『言語政策とは何か』 白水社,2000年.

2013-04-29 Mon

■ #1463. euphuism [style][literature][inkhorn_term][johnson][emode][renaissance][alliteration][rhetoric]

「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) で,15世紀に発生したラテン借用語を駆使する華麗語法について見た.続く16世紀には,inkhorn_term と呼ばれるほどのラテン語かぶれした語彙が押し寄せた.これに伴い,エリザベス朝の文体はラテン作家を範とした技巧的なものとなった.この技巧は John Lyly (1554--1606) によって最高潮に達した.Lyly は,Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit (1578) および Euphues and His England (1580) において,後に標題にちなんで呼ばれることになった euphuism (誇飾体)という華麗な文体を用い,初期の Shakespeare など当時の文芸に大きな影響を与えた.

euphuism の特徴としては,頭韻 (alliteration),対照法 (antithesis),奇抜な比喩 (conceit),掛けことば (paronomasia),故事来歴への言及などが挙げられる.これらの修辞法をふんだんに用いた文章は,不自然でこそあれ,人々に芸術としての散文の魅力をおおいに知らしめた.例えば,Lyly の次の文を見てみよう.

If thou perceive thyself to be enticed with their wanton glances or allured with their wicket guiles, either enchanted with their beauty or enamoured with their bravery, enter with thyself into this meditation.

ここでは,enticed -- enchanted -- enamoured -- enter という語頭韻が用いられているが,その間に wanton glances と wicket guiles の2重頭韻が含まれており,さらに enchanted . . . beauty と enamoured . . . bravery の組み合わせ頭韻もある.

euphuism は17世紀まで見られたが,17世紀には Sir Thomas Browne (1605--82), John Donne (1572--1631), Jeremy Taylor (1613--67), John Milton (1608--74) などの堂々たる散文が現われ,世紀半ばからの革命期以降には John Dryden (1631--1700) に代表される気取りのない平明な文体が優勢となった.平明路線は18世紀へも受け継がれ,Joseph Addison (1672--1719), Sir Richard Steele (1672--1729), Chesterfield (1694--1773),また Daniel Defoe (1660--1731), Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が続いた.だが,この平明路線は,世紀半ば,Samuel Johnson (1709--84) の荘重で威厳のある独特な文体により中断した.

初期近代英語期の散文文体は,このように華美と平明とが繰り返されたが,その原動力がルネサンスの熱狂とそれへの反発であることは間違いない.ほぼ同時期に,大陸諸国でも euphuism に相当する誇飾体が流行したことを付け加えておこう.フランスでは préciosité,スペインでは Gongorism,イタリアでは Marinism などと呼ばれた(ホームズ,p. 118).

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ 石橋 幸太郎 編 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

・ U. T. ホームズ,A. H. シュッツ 著,松原 秀一 訳 『フランス語の歴史』 大修館,1974年.

2013-03-08 Fri

■ #1411. 初期近代英語に入った "oversea language" [emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][lexicology][loan_word][french][italian][spanish][portuguese]

「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) の記事で,この時代の英語が抱えていた3つ目の問題として "the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" を挙げた.この3日間の記事 ([2013-03-05-1], [2013-03-06-1], [2013-03-07-1]) で,古典語からの大量の語彙借用という潮流によって反動的に引き起こされたインク壺語論争や純粋主義者による古語への回帰の運動について見てきた.異なる陣営から "inkhorn terms" や "Chaucerisms" への批判がなされたわけだが,もう1つ,あまり目立たないのだが,槍玉に挙げられた語彙がある."oversea language" と呼ばれる,ラテン語やギリシア語以外の言語からの借用語である.大量の古典語借用へと浴びせられた批判のかたわらで,いわばとばっちりを受ける形で,他言語からの借用語も非難の対象となった.

「#151. 現代英語の5特徴」 ([2009-09-25-1]) や「#110. 現代英語の借用語の起源と割合」で触れたように,現代英語は約350の言語から語彙を借用している.初期近代英語の段階でも英語はすでに50を超える言語から語彙を借用しており (Baugh and Cable, pp. 227--28) ,「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」 ([2009-08-19-1]) で見たように,ラテン語とギリシア語を除けば,フランス語,イタリア語,スペイン語が優勢だった.

以下,Baugh and Cable (228--29) よりロマンス諸語からの借用語を示そう.まずは,フランス語から入った借用語のサンプルから.

alloy, ambuscade, baluster, bigot, bizarre, bombast, chocolate, comrade, detail, duel, entrance, equip, equipage, essay, explore, genteel, mustache, naturalize, probability, progress, retrenchment, shock, surpass, talisman, ticket, tomato, vogue, volunteer

次に,イタリア語からは建築関係の語彙が多い.赤字のものはフランス語化して入ってきたイタリア語起源の語である.

algebra, argosy, balcony, battalion, bankrupt, bastion, brigade, brusque, cameo, capricio (caprice), carat, cavalcade, charlatan, cupola, design, frigate, gala, gazette, granite, grotesque, grotto, infantry, parakeet, piazza, portico, rebuff, stanza, stucco, trill, violin, volcano

スペイン語(およびポルトガル語)からは,海事やアメリカ植民地での活動を映し出す語彙が多い.赤字はフランス語化して入ったもの.

alligator, anchovy, apricot, armada, armadillo, banana, barricade, bastiment, bastinado, bilbo, bravado, brocade, cannibal, canoe, cavalier, cedilla, cocoa, corral, desperado, embargo, escalade, grenade, hammock, hurricane, maize, mosquito, mulatto, negro, palisade, peccadillo, potato, renegado, rusk, sarsaparilla, sombrero, tobacco, yam

上に赤字で示したように,フランス語経由あるいはフランス語化した形態で入ってきた語が少なからず確認される.これは,イタリア語やスペイン語から,同じような語彙が英語へもフランス語へも流入したからである.その結果として,異なるロマンス諸語の語形が融合したかのようにみえる例が散見される.例えば,英語 galleon は F. galion, Sp. galeon, Ital. galeone のどの語形とも一致しないし,gallery もソースは Fr. galerie, Sp., Port., Ital. galeria のいずれとも決めかねる.同様に,pistol は F. pistole, Sp., Ital. pistola のいずれなのか,cochineal は F. cochenille, Sp. cochinilla, Ital. cocciniglia のいずれなのか,等々.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-07 Thu

■ #1410. インク壺語批判と本来語回帰 [inkhorn_term][lexicology][emode][renaissance][chaucer][loan_translation][purism]

昨日の記事「#1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語」 ([2013-03-06-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で,初期近代英語期あるいはルネサンス期のインク壺語批判を眺めてきた.ラテン語やギリシア語からの無差別な借用を批判する論者としては,「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) で触れたように,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Sir Thomas Chaloner, Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) などの名前が挙がるが,このなかでも Cheke のような論者はその反動で純粋主義に走り,本来語への回帰を主張した.新しい語彙が必要なのであれば,誰にでもわかる本来語要素を用いた造語を用いるのが得策であり,小難しい借用語など百害あって一利なしだという考えだ.同じ考えをもち,ともに古典語学者である Ascham とともに,Cheke はこの時期における簡潔にして明快な英語の書き手として評価されている.

例えば,Cheke はマタイ伝の翻訳にあたって,欽定訳聖書 (The King James Bible) では借用語が使われているところで,本来語に由来する語を用いた.lunatic に対して mooned,publican に対して toller,その他 hundreder (centurion), foresayer (prophet), byword (parable), freshman (proselyte), crossed (crucified), gainrising (resurrection) .まさに purist らしい,古色蒼然たるゲルマン語への回帰だ.

Cheke のような人物とはやや異なる動機づけで,詩人たちもまた古語への回帰を示す傾向が強かった.ラテン語彙があふれる時代にあって,Chaucer 時代への憧憬が止みがたかったのだろうか,Edmund Spenser (1552/53--99) は "Chaucerism" とも呼ばれる古語への依存を強めた詩人として知られる.Horace の翻訳者 Thomas Drant や,John Milton (1608--74) も古語回帰の気味があった.彼らの詩においては,astound, blameful, displeasance, enroot, forby (hard by, past), empight (fixed, implanted), natheless, nathemore, mickle, whilere (a while before) などの本来語が復活した.ほかにも,ゲルマン語要素を(少なくとも部分的に)もとにした(と想定される)語形成や古語としては以下のものがある.

askew, baneful, bellibone (a fair maid), belt, birthright, blandishment, blatant, braggadocio, briny, changeful, changeling, chirrup, cosset (lamb), craggy, dapper, delve (pit, den), dit (song), don, drear, drizzling, elfin, endear, enshrine, filch, fleecy, flout, forthright, freak, gaudy, glance, glee, glen, gloomy, grovel, hapless, merriment, oaten, rancorous, scruze (squeeze, crush), shady, squall (to cry), sunshiny, surly, wakeful, wary, witless, wolfish, wrizzled (wrinkled, shriveled)

これらの純粋主義者による反動的な運動は,それ自体も批判を浴びることがあったが,上記語彙のなかには,現在,一般的に用いられているものも含まれている.インク壺批判には,英語語彙史上,このように生産的な側面もあったことを見逃してはならない.以上,Baugh and Cable (230--31) を参照して記述した.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-06 Wed

■ #1409. 生き残ったインク壺語,消えたインク壺語 [inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek]

昨日の記事「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で,初期近代英語期に大量に流入した古典語由来の小難しい借用語の話題を扱ってきた.「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) で挙げたように,当時は「インク壺語」と揶揄されながらも,現代にまで生き残った有用な語も多い.一方で,現代にまで伝わらなかった語も少なくない.今回は,Baugh and Cable (223--24, 226) から,生き残った語彙とほぼ死に絶えた語彙の例をさらに追加したい.

まずは生き残った語彙のサンプルを,名詞,形容詞,動詞の順に挙げる.大半はラテン語由来だが,赤字で示したようにギリシア語由来のもの(ラテン語を経由したものを含む)も多い.

acme, allurement, allusion, anachronism, antipathy, antithesis, atmosphere, autograph, capsule, catastrophe, chaos, chronology, climax, crisis, criterion, democracy, denunciation, dexterity, disability, disrespect, dogma, emanation, emphasis, encyclopedia, enthusiasm, epitome, excrescence, excursion, expectation, halo, idiosyncrasy, inclemency, jurisprudence, lexicon, misanthrope, parasite, parenthesis, pathetic, pneumonia, scheme, skeleton, system, tactics, thermometer

abject, agile, anonymous, appropriate, caustic, conspicuous, critic, dexterous, ephemeral, expensive, external, habitual, hereditary, heterodox, impersonal, insane, jocular, malignant, polemic, tonic

adapt, alienate, assassinate, benefit, consolidate, disregard, emancipate, eradicate, erupt, excavate, exert, exhilarate, exist, extinguish, harass, meditate, ostrasize, tantalize

次に,死語あるいは事実上の廃用となったもののサンプルを,名詞,形容詞,動詞の順に,語義とともに挙げる.

adminiculation (aid), appendance (appendage), assation (roasting), discongruity (incongruity), mansuetude (mildness)

aspectable (visible), eximious (excellent, distinguished), exolete (faded), illecebrous (delicate, alluring), temulent (drunk)

approbate (to approve), assate (to roast), attemptate (to attempt), cautionate (to caution), cohibit (to restrain), consolate (to console), consternate (to dismay), demit (to send away), denunciate (to denounce), deruncinate (to weed), disaccustom (to render unaccustomed), disacquaint (to make acquainted), disadorn (to deprive of adornment), disquantity (to diminish), emacerate (to emaciate), exorbitate (to stray from the ordinary course), expede (to accomplish, expedite), exsiccate (to desiccate), suppeditate (to furnish, supply)

湯水の如き借用は実験的な借用ともいうことができる.実験的な性格は,現在も用いられている effective, effectual に加えて,effectful, effectuating, effectuous などがかつて使われていた事実からも知れるだろう.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-05 Tue

■ #1408. インク壺語論争 [popular_passage][inkhorn_term][loan_word][lexicology][emode][renaissance][latin][greek][purism]

16世紀のインク壺語 (inkhorn term) を巡る問題の一端については,昨日の記事「#1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題」 ([2013-03-04-1]) 以前にも,「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]) ,「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]) ほか inkhorn_term の各記事で触れてきた.インク壺語批判の先鋒としては,[2010-11-24-1]で引用した The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) の著者 Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) が挙げられるが,もう1人挙げるとするならば Sir John Cheke (1514--57) がふさわしい.Cheke は自らがギリシア語学者でありながら,古典語からのむやみやたらな借用を強く非難した.同じくギリシア語学者である Roger Ascham (1515?--68) も似たような態度を示していた点が興味深い.Cheke は Sir Thomas Hoby に宛てた手紙 (1561) のなかで,純粋主義の主張を行なった(Baugh and Cable, pp. 217--18 より引用).

I am of this opinion that our own tung shold be written cleane and pure, unmixt and unmangeled with borowing of other tunges, wherin if we take not heed by tijm, ever borowing and never payeng, she shall be fain to keep her house as bankrupt. For then doth our tung naturallie and praisablie utter her meaning, when she bouroweth no counterfeitness of other tunges to attire her self withall, but useth plainlie her own, with such shift, as nature, craft, experiens and folowing of other excellent doth lead her unto, and if she want at ani tijm (as being unperfight she must) yet let her borow with suche bashfulnes, that it mai appeer, that if either the mould of our own tung could serve us to fascion a woord of our own, or if the old denisoned wordes could content and ease this neede, we wold not boldly venture of unknowen wordes.

Erasmus の Praise of Folly を1549年に英訳した Sir Thomas Chaloner も,インク壺語の衒学たることを揶揄した(Baugh and Cable, p. 218 より引用).

Such men therfore, that in deede are archdoltes, and woulde be taken yet for sages and philosophers, maie I not aptelie calle theim foolelosophers? For as in this behalfe I have thought good to borowe a littell of the Rethoriciens of these daies, who plainely thynke theim selfes demygods, if lyke horsleches thei can shew two tongues, I meane to mingle their writings with words sought out of strange langages, as if it were alonely thyng for theim to poudre theyr bokes with ynkehorne termes, although perchaunce as unaptly applied as a gold rynge in a sowes nose. That and if they want suche farre fetched vocables, than serche they out of some rotten Pamphlet foure or fyve disused woords of antiquitee, therewith to darken the sence unto the reader, to the ende that who so understandeth theim maie repute hym selfe for more cunnyng and litterate: and who so dooeth not, shall so muche the rather yet esteeme it to be some high mattier, because it passeth his learnyng.

"foolelosophers" とは厳しい.

このようにインク壺語批判はあったが,時代の趨勢が変わることはなかった.インク壺語を(擁護したとは言わずとも)穏健に容認した Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546) や Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) などの主たる人文主義者たちの示した態度こそが,時代の潮流にマッチしていたのである.

なお,OED によると,ink-horn term という表現の初出は1543年.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2013-03-04 Mon

■ #1407. 初期近代英語期の3つの問題 [emode][renaissance][popular_passage][orthoepy][orthography][spelling_reform][standardisation][mulcaster][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicology][hart]

初期近代英語期,特に16世紀には英語を巡る大きな問題が3つあった.Baugh and Cable (203) の表現を借りれば,"(1) recognition in the fields where Latin had for centuries been supreme, (2) the establishment of a more uniform orthography, and (3) the enrichment of the vocabulary so that it would be adequate to meet the demands that would be made upon it in its wiser use" である.

(1) 16世紀は,vernacular である英語が,従来ラテン語の占めていた領分へと,その機能と価値を広げていった過程である.世紀半ばまでは,Sir Thomas Elyot (c1490--1546), Roger Ascham (1515?--68), Thomas Wilson (1525?--81) , George Puttenham (1530?--90) に代表される英語の書き手たちは,英語で書くことについてやや "apologetic" だったが,世紀後半になるとそのような詫びも目立たなくなってくる.英語への信頼は,特に Richard Mulcaster (1530?--1611) の "I love Rome, but London better, I favor Italie, but England more, I honor the Latin, but I worship the English." に要約されている.

(2) 綴字標準化の動きは,Sir John Cheke (1514--57), Sir Thomas Smith (1513--77; De Recta et Emendata Linguae Anglicae Scriptione Dialogus [1568]), John Hart (d. 1574; An Orthographie [1569]), William Bullokar (fl. 1586; Book at Large [1582], Bref Grammar for English [1586]) などによる急進的な表音主義的な諸提案を経由して,Richard Mulcaster (The First Part of the Elementarie [1582]), E. Coot (English Schoole-master [1596]), P. Gr. (Paulo Graves?; Grammatica Anglicana [1594]) などによる穏健な慣用路線へと向かい,これが主として次の世紀に印刷家の支持を受けて定着した.

(3) 「#478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語」 ([2010-08-18-1]),「#576. inkhorn term と英語辞書」 ([2010-11-24-1]),「#1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布」 ([2012-09-04-1]) などの記事で繰り返し述べてきたように,16世紀は主としてラテン語からおびただしい数の借用語が流入した.ルネサンス期の文人たちの多くが,Sir Thomas Elyot のいうように "augment our Englysshe tongue" を目指したのである.

vernacular としての初期近代英語の抱えた上記3つの問題の背景には,中世から近代への急激な社会変化があった.再び Baugh and Cable (200) を参照すれば,その要因は5つあった.

1. the printing press

2. the rapid spread of popular education

3. the increased communication and means of communication

4. the growth of specialized knowledge

5. the emergence of various forms of self-consciousness about language

まさに,文明開化の音がするようだ.[2012-03-29-1]の記事「#1067. 初期近代英語と現代日本語の語彙借用」も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2012-09-04 Tue

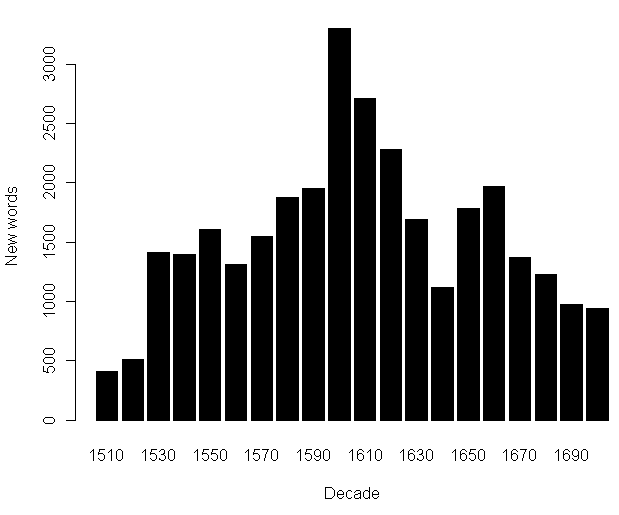

■ #1226. 近代英語期における語彙増加の年代別分布 [loan_word][lexicology][statistics][emode][renaissance][inkhorn_term][latin]

英語史における借用語の最たる話題として,中英語期におけるフランス語彙の著しい流入が挙げられる.この話題に関しては,語彙統計の観点からだけでも,「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) を始めとして,french loan_word statistics のいくつかの記事で取り上げてきた.しかし,語彙統計ということでいえば,近代英語期のラテン借用語を核とする語彙増加のほうが記録的である.

[2009-08-19-1]の記事「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」で言及したが,Görlach は初期近代英語の語彙の著しい増大を次のように評価し,説明している.

The EModE period (especially 1530--1660) exhibits the fastest growth of the vocabulary in the history of the English language, in absolute figures as well as in proportion to the total. (136)

. . . the general tendencies of development are quite obvious: an extremely rapid increase in new words especially between 1570 and 1630 was followed by a low during the Restoration and Augustan periods (in particular 1680--1780). The sixteenth-century increase was caused by two factors: the objective need to express new ideas in English (mainly in fields that had been reserved to, or dominated by, Latin) and, especially from 1570, the subjective desire to enrich the rhetorical potential of the vernacular. / Since there were no dictionaries or academics to curb the number of new words, an atmosphere favouring linguistic experiments led to redundant production, often on the basis of competing derivation patterns. This proliferation was not cut back until the late seventeenth/eighteenth centuries, as a consequence of natural selection or a s a result of grammarians' or lexicographers' prescriptivism. (137--38)

Görlach は,A Chronological English Dictionary に基づいて,次のような語彙統計も与えている (137) .これを図示してみよう.

| Decade | 1510 | 1520 | 1530 | 1540 | 1550 | 1560 | 1570 | 1580 | 1590 | 1600 | 1610 | 1620 | 1630 | 1640 | 1650 | 1660 | 1670 | 1680 | 1690 | 1700 |

| New words | 409 | 508 | 1415 | 1400 | 1609 | 1310 | 1548 | 1876 | 1951 | 3300 | 2710 | 2281 | 1688 | 1122 | 1786 | 1973 | 1370 | 1228 | 974 | 943 |

近代英語期のラテン借用について関連する話題は,「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1]) や emode loan_word lexicology の各記事を参照.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

・ Finkenstaedt, T., E. Leisi, and D. Wolff, eds. A Chronological English Dictionary. Heidelberg: Winter, 1970.

2010-12-22 Wed

■ #604. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (2) [lexicography][dictionary][punctuation][inkhorn_term][cawdrey]

昨日の記事[2010-12-21-1]に引き続き,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) の話題.この史上初の一般向け英英辞書には,当時の英語やそれが社会のなかに置かれていた状況を示唆する様々な情報の断片が含まれている.A Table Alphabeticall にまつわるエトセトラとでもいうべき雑多な話題を以下に記そう.

(1) [2010-12-04-1]の記事で引用したように,タイトルページには,この辞書が一般庶民のために難しい日常語を易しい英語で解説することを旨としていることが明言されている.しかし,その下に続く1節も,本辞書の出版意図を探る上で重要なので,初版から引用しよう.

Whereby they may the more easilie and better vnderstand many hard English wordes, which they shall heare or read in Scriptures, Sermons, or elswhere, and also be made able to vse the same aptly themselues.

ここでは,Cawdrey が辞書編纂者である以前に村の聖職者であったこと,しかも頑固な Puritan として教会当局に目をつけられて裁判沙汰にもなっていたことが関係している.聖書などにも含まれる難語をいかにして一般聴衆によく理解させるかに腐心していた説教師 Cawdrey の一面が垣間見られる.実際に,宗教関係の用語の多くが見出し語として採用されている ( Simpson 15 ) .

(2) Siemens の分析によると,定義部の文体に,見出し語の品詞ごとに一定の構造が認められる.これは辞書史を論じる上でも重要な視点である.Siemens の論文は Siemens: Lexicographical Method in Cawdrey で閲覧可能.

(3) 辞書内で使われている綴字には緩やかな標準化の方向が感じられるが ( see [2010-12-04-1] ) ,句読法 ( punctuation ) にはそれが感じられない.例えば,定義を終えるのにピリオドの場合もあれば,セミコロンの場合もあり,何もない場合も多い ( Simpson 22 ) .

(4) 語源情報が貧弱.同時代の辞書でも語源情報は同じように貧弱であり,その時代としては無理もない.見出し語は無印であればラテン語借用語であることが前提とされ,フランス語やギリシア語の場合には省略記号が付される.このように提供側言語が示されるのみで,それ以上の語源情報は与えられていない.

(5) Cawdrey 自身,ynckhorne termes を序文 "To the Reader" で攻撃している(赤字は転記者).

SVch as by their place and calling, (but especially Preachers) as haue occasion to speak publiquely before the ignorant people, are to bee admonished, that they neuer affect any strange ynckhorne termes, but labour to speake so as is commonly receiued, and so as the most ignorant may well vnderstand them: . . . .

(6) 当然ながら見出し語はアルファベット順に並んでいるが,驚くことに当時の読者にとってはこれは自明のことではなかったようだ.というのは,Cawdrey は序文 "To the Reader" で辞書の引き方の指示を次のようにしているからである.

If thou be desirous (general Reader) rightly and readily to vnderstand, and to profit by this Table, and such like, then thou must learne the Alphabet, to wit, the order of the Letters as they stand, perfecty without booke, and where euery Letter standeth: as (b) neere the beginning, (n) about the middest, and (t) toward the end. Nowe if the word, which thou art desirous to finde, begin with (a) then looke in the beginning of this Table, but if with (v) looke towards the end. Againe, if thy word beginne with (ca) looke in the beginning of the letter (c) but if with (cu) then looke toward the end of that letter. And so of all the rest. &c.

(7) 初版では2543語が見出しに採用されたが,続く1609, 1613, 1617年の版ではそれぞれ3009, 3086, 3264語へと増補された(2版以降に Cawdrey 自身が関わった形跡がないことから,初版直後に亡くなったのではないかと推測されている).John Bullokar の An English Expositor: Teaching the Interpretation of the hardest words used in our language (1616) が現われてからは,A Table Alphabeticall の人気は一気に衰えたようである ( Simpson 29 ) .

(8) 初版に基づいてHTML化された電子版,本辞書の解説,参考文献が A Table Alphabeticall of Hard Usual English Words (R. Cawdrey, 1604) で入手可能である.

・ Simpson, John. The First English Dictionary, 1604: Robert Cawdrey's A Table Alphabeticall. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2007.

・ Bately, Janet. "Cawdrey, Robert (b. 1537/8?, d. in or after 1604)." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Ed. Lawrence Goldman. Oxford: OUP. Accessed on 19 Dec. 2010.

2010-12-21 Tue

■ #603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1) [lexicography][dictionary][inkhorn_term][cawdrey]

[2010-11-24-1], [2010-12-04-1]の記事で,Robert Cawdrey (1537/38--1604) の A Table Alphabeticall (1604) が,英語史上,英英辞書の第1号であることを紹介した.Simpson (18) によれば,"As far as is known, it [A Table Alphabeticall] is the first dictionary published in book form addressed to the general reader which defines 'usual' English words in English." ということである.今回は,Simpson のこの引用を参照して,A Table Alphabeticall が最初の英英辞書であるということは何を意味するのかを考えてみたい.

まず第1に,英単語を見出しとする初の monolingual 辞書であるという点 ( "English words in English" ) が重要である.少し考えてみればすぐに分かることだが,羅英辞書,仏英辞書,伊英辞書などの2カ国語辞書 ( bilingual dictionary ) の出版のほうが,1言語辞書 ( monolingual dictionary ) の出版よりも早い.辞書の本来の目的は,未知の外国語単語を既知の自国語単語へ翻訳することであるからだ.たとえ辞書という立派な体裁をなしていなくとも,対訳単語リストの形で本の付録などについていたものを合わせると,すでに2カ国語辞書といえるものは出版されていた.しかし,英英辞書は Cawdrey のものが初だったのである.ただし,A Table Alphabeticall が bilingual dictionary と monolingual dictionary の中間的な辞書であったことは確かである.というのは,含まれている見出し語はすべてラテン語を中心とした借用語であり,それをわかりやすい英単語へ翻訳するというのがこの辞書の意図だったからである.ちなみに,大陸の他の言語ではすでに同種の1言語辞書はいくつか出版されており,あくまで「英英」として最初のものであったことを指摘しておきたい.

第2に,"'usual' English words" を取りあげ,読者層として "the general reader" を想定した点.(1) で1言語辞書としては最初のものであった述べたが,専門語辞書であれば先行する1言語辞書は存在した.しかし,後者は当然専門家向けであり,一般大衆向けの1言語辞書は存在しなかった.16世紀の終わりまでに inkhorn terms ( see inkhorn_term ) を含めた大量の難解な日常語が蓄積されてきたことにより,一般向けに難しい日常語を解説する辞書の需要が増してきた.このタイミングで出版されたのが A Table Alphabeticall だったのである.

上の2点から,Cawdrey にとって先行するお手本はいくつか存在していたことが分かる.例えば,[2010-07-12-1]の記事で触れた Edmund Coote の出版した The English schoole-maister: teaching all his scholers, the order of distinct reading, and true writing our English tongue (1596) や,Thomas Thomas の Dictionarium Linguae Latinae et Anglicanae (1587) は,見出しや定義に関して頻繁に参照された形跡がある(ある推計によると Cawdrey は見出し語の17--18%を両者に拠っている; see Siemens: Lexicographical Method in Cawdrey. ).こうしてみると,A Table Alphabeticall は Cawdrey の完全なオリジナルとはいえないのかもしれないが,歴史上の「最初の」という形容は,時代の潮流に乗り,人々の要求をつかんで,あるものを形として残した場合に与えられる称号なのだろう.この難語解説辞書の出版は,Cawdrey が Rutland (現在の Leicestershire の一部)の村の聖職者として,日々,人々にわかりやすく説教をする必要を感じていたこととも無関係ではない.時代の流れと人生の志とがかみ合ったときに,この歴史的な著作が世に現われたのである.

・ Simpson, John. The First English Dictionary, 1604: Robert Cawdrey's A Table Alphabeticall. Oxford: Bodleian Library, 2007.

2010-11-24 Wed

■ #576. inkhorn term と英語辞書 [emode][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][lexicography][cawdrey][lexicology][popular_passage]

[2010-08-18-1]の記事で「インク壺語」( inkhorn term )について触れた.16世紀,ルネサンスの熱気にたきつけられた学者たちは,ギリシア語やラテン語から大量に語彙を英語へ借用した.衒学的な用語が多く,借用の速度もあまりに急だったため,これらの語は保守的な学者から inkhorn terms と揶揄されるようになった.その代表的な批判家の1人が Thomas Wilson (1528?--81) である.著書 The Arte of Rhetorique (1553) で次のように主張している.

Among all other lessons this should first be learned, that wee never affect any straunge ynkehorne termes, but to speake as is commonly received: neither seeking to be over fine nor yet living over-carelesse, using our speeche as most men doe, and ordering our wittes as the fewest have done. Some seeke so far for outlandish English, that they forget altogether their mothers language.

Wilson が非難した "ynkehorne termes" の例としては次のような語句がある.ex. revolting, ingent affabilitie, ingenious capacity, magnifical dexteritie, dominicall superioritie, splendidious.このラテン語かぶれの華美は,[2010-02-13-1]の記事で触れた15世紀の aureate diction 「華麗語法」の拡大版といえるだろう.

inkhorn controversy は16世紀を通じて続くが,その副産物として英語史上,重要なものが生まれることになった.英語辞書である.inkhorn terms が増えると,必然的に難語辞書が求められるようになった.Robert Cawdrey (1580--1604) は,1604年に約3000語の難語を収録し,平易な定義を旨とした A Table Alphabeticall を出版した(表紙の画像はこちら.そして,これこそが後に続く1言語使用辞書 ( monolingual dictionary ) すなわち英英辞書の先駆けだったのである.現在,EFL 学習者は平易な定義が売りの各種英英辞書にお世話になっているが,その背景には16世紀の inkhorn terms と inkhorn controversy が隠れていたのである.

A Table Alphabeticall については,British Museum の解説が有用である.

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2003.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

2010-08-18 Wed

■ #478. 初期近代英語期に湯水のように借りられては捨てられたラテン語 [emode][loan_word][latin][inkhorn_term][ranaissance][lexicology]

[2009-08-19-1],[2009-11-05-1]などで触れたように,近代英語期にはものすごい勢いでラテン単語が英語に借用された.その勢いは中英語期のフランス語借用をも上回るほどである.[2009-06-12-1]で示したように,16世紀だけでも7000語ほどが借用されたというから凄まじい.背景には以下のような事情があった.

16世紀後半,中英語期のフランス語のくびきから解放され,自信を回復しつつあった英語にとっての大きな悩みは,本格的に聖書を英訳するにあたって自前の十分な語彙を欠いていたことだった.そこで考えられた最も効率のよい方法は,直接ラテン語から語彙を借用することだった.さらに,ルネサンスのもたらした新しい思想や科学,古典の復活により,ギリシア語やラテン語といった古典語に由来する無数の専門用語が必要とされ,英語に流入したという事情もあった.かくして16世紀後半の数十年ほどの短期間に,大量のラテン単語が英語に取り込まれた.しかし「インク壺語」( inkhorn term )と揶揄されるほどに難解で衒学的な借用語も多く,この時期に入ったラテン単語の半分は現代にまで伝わっていないと言われる.

現代にまで残ったものは,基本語彙とまでは言わないが,文章では比較的よくみかける次のような単語が挙げられる(以下,Brinton and Arnovick, pp. 357--58 より).

confidence, dedicate, describe, discretion, education, encyclopedia, exaggerate, expect, industrial, maturity

現代までに残らなかったものは,以下のような単語である.当然ながら我々には馴染みのない単語ばかりなので,ラテン語を勉強していない限り意味を推測するのは困難だ.

adjuvate "aid", deruncinate "weed", devulgate "set forth", eximious "excellent", fatigate "make tired", flantado "flaunting", homogalact "foster-brother", illecebrous "delicate", pistated "baked", suppeditate "supply"

どの語が生き残りどの語が捨てられたのかについては,理由らしい理由はないといってよいだろう.ランダムに受容され,ランダムに廃棄されたと考えるのが妥当だ.現代英語に慣れている感覚では,education や expect などの語がなかったら不便だろうなと思う一方で,flantado や illecebrous などは必要のない語に思える.だが,場合によってはまったく逆の状況が生じていた可能性があると想像すると不思議である.現代英語の語彙が歴史の偶然によってもたらされたものだということがよく分かるだろう.

・ Brinton, Laurel J. and Leslie K. Arnovick. The English Language: A Linguistic History. Oxford: OUP, 2006.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow