2024-11-15 Fri

■ #5681. 山口美知代先生との3回の heldio 対談 [voicy][heldio][notice][world_englishes][we_nyumon][caribbean][variety][jamaica][creole][review][spelling_reform][orthography]

去る10月,山口美知代先生(京都府立大学)と Voicy heldio で3度にわたり対談させていただきました.

最初の2回は,昨年昭和堂より出版された『World Englishes 入門』の共著者のお一人として世界英語 (world_englishes) について,とりわけ「カリブ海の英語」と「中華世界の英語」について,お話しを賜わりました.

・ 「#1231. 著者と語る『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年) --- 山口美知代先生とのカリブ海の英語をめぐる対談」(2024年10月12日配信)

・ 「#1235. 著者と語る『World Englishes 入門』(昭和堂,2023年) --- 山口美知代先生との中華世界の英語をめぐる対談」(2024年10月16日配信)

「カリブ海の英語」は,おそらく多くの方々にとってあまり馴染みのない変種と思われますが,それだけに英語の世界の奥深さが伝わるはずです.一方,「中華世界の英語」はずっと身近な気はするものの,具体的には知らないことが意外と多いのではないでしょうか.

2回の対談を通じて,世界の隅々で英語が用いられていることが再確認できたと思います.ぜひ,これまでの『World Englishes 入門』関連の hellog 記事や heldio 対談回へ,we_nymon を通じてアクセスしていただければ.

さて,山口先生との第3回目の対談回では,今年開拓社より出版されました単著『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』について,著者直々にご紹介いただきました.「#1241. 著者と語る『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』(開拓社,2024年) --- 山口美知代先生との対談」(2024年10月22日配信)をお聴きください.

『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』については,今年の4月11日の heldio にて私単独で「#1046. 山口美知代『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』(開拓社,2024年)」としても紹介していますので,そちらもお聴きください.hellog 記事としては「#5469. 山口美知代『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』(開拓社,2024年)」 ([2024-04-17-1]) をどうぞ.

山口先生,お忙しいところ,対談のお時間を割いていただきまして,ありがとうございました!

・ 大石 晴美(編) 『World Englishes 入門』 昭和堂,2023年.

・ 山口 美知代 『ハリウッド映画と英語の変化』 開拓社,2024年.

2021-12-03 Fri

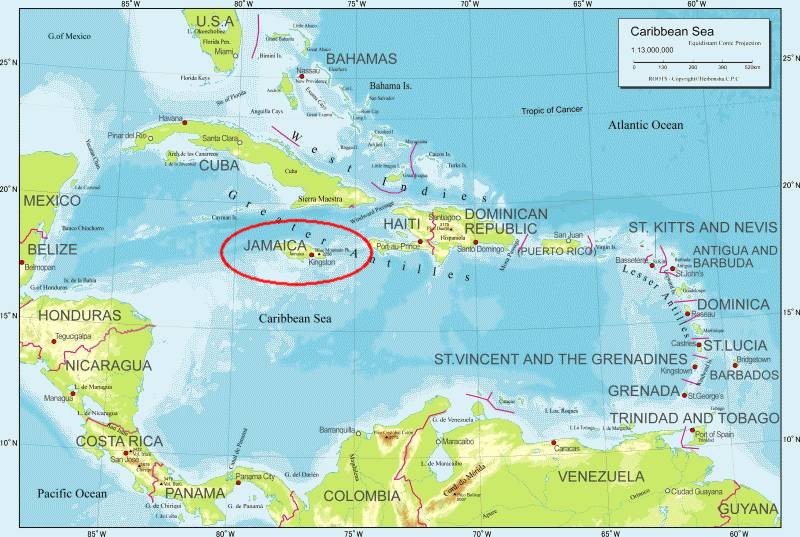

■ #4603. Jamaican Creole の連続体 [jamaica][creole][post-creole_continuum][caribbean][variety][map]

昨日の記事「#4602. Barbados が立憲君主制から共和制へ」 ([2021-12-02-1]) で,カリブ海地域の英語事情の1つの典型を示すバルバドスの歴史を略述した.英語事情と関連して同地域よりもう1つ重要な国を挙げるのであれば,間違いなくジャマイカだろう.「#1680. The West Indies の言語事情」 ([2013-12-02-1]) で触れたように,バルバドスと同様にジャマイカでも英語ベースのクレオールが行なわれている.

ジャマイカでは,Jamaican Creole は下層語 (basilect) として用いられており,それに対して標準(ジャマイカ)英語が上層語 (acrolect) として使われている.両者の間には中層語 (mesolect) の多数の変種が認められ,典型的な post-creole_continuum) を構成している言語社会といってよい.この連続体について,Sand (2125) を参照して見てみよう(cf. 「#385. Guyanese Creole の連続体」 ([2010-05-17-1]) とも比較).

| Standard (Jamaican) English | he went down there | ↑ | Acrolect |

| he wen dong de | | | ||

| (h)im go dong de | | | ||

| (h)im dida go dong de | | | Mesolect | |

| (h)im neva go dong de (negative only) | | | ||

| Jamaican Creole | im ben go dong de | ↓ | Basilect |

中層を構成する変種間の高低は定めがたいが,全体として連続体をなしているらしいことは分かるだろう.同一話者が場合によっては連続体のすべての変種を使いこなすというケースもあるという.また,少なくとも自分の常用する変種の近くの変種については,自らは話さずとも理解することはできるともいわれる.

数十年前のジャマイカでは公的な場面で下層・中層の変種を用いることは考えられなかったが,最近では少なくとも中層の変種はメディアや教育の場などで許容されるようになってきているという (Sand 2125) .

・ Sand, Andrea. "Second-Language Varieties: English-Based Creoles." Chapter 135 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 2120--34.

[ 固定リンク | 印刷用ページ ]

2021-12-02 Thu

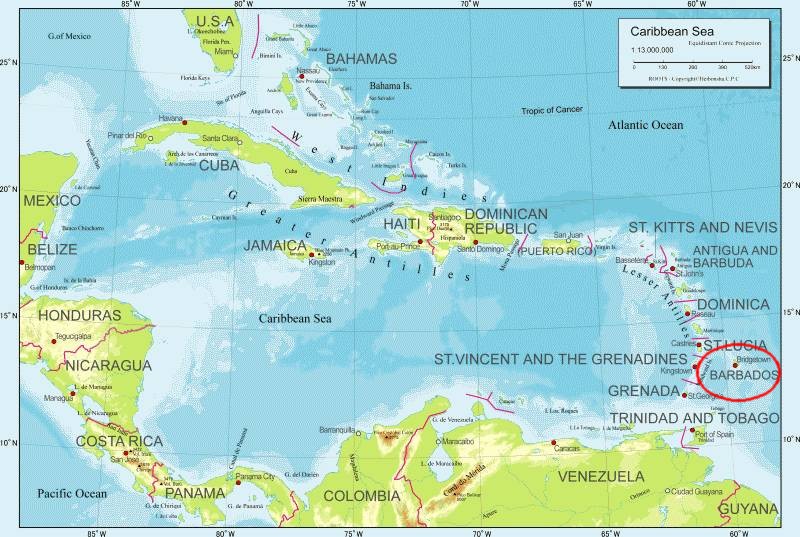

■ #4602. Barbados が立憲君主制から共和制へ [barbados][caribbean][history][creole][map]

昨日12月1日付けで,西インド諸島の小アンティル諸島にあるバルバドスが共和国となった.英連邦には残るものの,イギリスのエリザベス女王を元首とする立憲君主制から共和制に移行したことになる(cf. 「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1])).同日,「女王の代理人」として総督を務めてきたサンドラ・メイソン氏が,バルバドスの初代大統領として就任した.就任式にはイギリスのチャールズ皇太子も参加し,平和な祝賀ではあったが,背景にはイギリス植民地としての歴史認識の見直しがあった.

この地へのイギリス人およびアイルランド人による入植は,4世紀ほど前の1627年にさかのぼる.当初は白人年季奉公労働者によるタバコ栽培で繁栄し,1642年には人口は3万7千人まで増えていた.しかし,疫病の流行と栽培品のサトウキビへの転換により,様相が一変した.サトウキビは広いプランテーションで栽培され,労働も過酷だったために,労働力がアフリカ出身の黒人奴隷によって置き換えられたのである.結果として,1685年には白人2万人に対して黒人4万6千人という人口比となっていた.現在,バルバドスの人口約29万人のうち,9割以上が黒人である.

17世紀後半に生じたこの人口構成の急激な変化は,バルバドスの言語状況にも多大な影響を及ぼした.それまでイギリス人とアイルランド人の話す英語が根づいていたが,この時期以降それがクレオール化したのである.Barbadian Creole (あるいは Bajun)と呼ばれるこのクレオール語は,現在,バルバドスにおいて標準英語とともに用いられている.バルバドスの英語事情の歴史は,この地域全体の英語事情の歴史を代表しているといってよい (Sand 2121) .

バルバドスは1966年にイギリスから独立したが,今回の共和制への移行は「第2の独立」という象徴的な意義をもつ.ほかにもエリザベス女王を元首とする立憲君主国はイギリス以外には世界に14カ国残っており,その多くが中米・カリブ海地域に位置する.今回のバルバドスの共和制移行を契機に,周辺諸国も続いていくのではないかという観測もなされている.

カリブ海地域における英語の歴史は,たいへんに複雑である.本ブログでも「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]),「#1700. イギリス発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-22-1]),「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]),「#1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散」 ([2014-01-02-1]) ほか caribbean の各記事で取り上げてきたので,そちらを参照されたい.

・ Sand, Andrea. "Second-Language Varieties: English-Based Creoles." Chapter 135 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 2120--34.

2016-10-26 Wed

■ #2739. AAVE の Creolist Hypothesis と Anglicist Hypothesis 再訪 [aave][creole][ame][sociolinguistics][dialect][variety][caribbean]

AAVE の起源について,Creolist Hypothesis と Anglicist Hypothesis が鋭く対立している経緯に関して,「#1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題」 ([2014-06-25-1]) で紹介し,その前後で関連する以下の記事も書いてきた

・ 「#1886. AAVE の分岐仮説」 ([2014-06-26-1])

・ 「#1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s」 ([2014-05-21-1])

・ 「#1841. AAVE の起源と founder principle」 ([2014-05-12-1])

Tagliamonte (9) より,両仮説を巡る論争について要領よくまとめている箇所があったので,引用し,補足としたい.

Among the varieties of English that arose from the colonial southern United States is that spoken by the contemporary descendants of the African populations --- often referred to as African American Vernacular English or by its abbreviation AAVE. This variety is quite distinct from Standard North American English. One of the most vexed questions of modern North American sociolinguistics is why this is the case. Early African American slaves would have acquired their variety of English either en route to the United States or more likely on the plantations and homesteads of the American South. But it is necessary to determine the nature of the varieties to which they were exposed. The fact that AAVE is so different has often been traced to the dialects from Northern Ireland, Scotland and England. However, they have as often been traced to African and Caribbean creoles. There is a long history of overly simplistic dichotomies on this issue which can be summarized as follows: (1) a 'creole origins hypothesis', based on linguistic parallels between AAVE and Caribbean creoles; (2) an 'English dialect hypothesis', based on linguistic parallels with the Irish and British dialects spoken by early plantation staff. In reality, the answer probably lies somewhere in between. Many arguments prevail based on one line of evidence or another. Perhaps the most damning is the lack of evidence of which populations were where and under what circumstances. / The debate over the origins of AAVE still rages on with no consensus in sight . . . .

北米植民の初期に生じた複雑な言語接触とその言語的余波を巡っての論争は,かれこれ100年間続いており,いまだに解決の目処が立っていない.言語接触に関与した種々の人々に関する,緻密な歴史社会言語学の研究が必要とされている.

・ Tagliamonte, Sali A. Roots of English: Exploring the History of Dialects. Cambridge: CUP, 2013.

2016-06-16 Thu

■ #2607. カリブ海地域のクレオール語の自律性を巡る議論 [creole][caribbean][sociolinguistics][variety]

カリブ海地域の英語事情について,「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]) を始めとする caribbean の各記事で話題にしてきた.カリブ海地域と一口にいっても,英語やクレオール語 (creole) の社会的な地位を巡る状況や議論は個々の土地で異なっており,容易に概括することは難しい.その土地において標準的な英語変種とみなされるもの (acrolect) と,言語的にそこから最も隔たっている英語ベースのクレオール変種 (basilect) との間に,多数の中間的な変種 (mesolects) が認められ,いわゆる post-creole continuum が観察されるケースでは,basilect に近い諸変種の社会的な位置づけ,すなわち社会言語学的な自律性 (autonomy) は不安定である(関連して「#385. Guyanese Creole の連続体」 ([2010-05-17-1]),「#1522. autonomy と heteronomy」 ([2013-06-27-1]),「#1523. Abstand language と Ausbau language」 ([2013-06-28-1]) を参照).

近年,多くの地域で basilect を構成する変種の自律性が公私ともに認められるようになってきていると言われるが,その認可の水準については地域によって温度差がある.例えば,Belize, Guyana, Jamaica のような社会では,acrolect と basilect の隔たりが十分に大きいと感じられており,後者クレオール変種の "Ausbau language" としての autonomy が擁護されやすい一方で,the Bahamas, Barbados, Trinidad などではクレオール諸変種は "intermediate creole varieties" (Winford 417) と呼ばれるほど,その土地の標準的な変種との距離が比較的近いために,その heteronomy が指摘されやすい.Winford (418--19) より,"The Autonomy of Creole Varieties" と題する節を引用しよう.

In the Anglophone Caribbean, the question of the autonomy of the creole vernaculars has long been fraught with controversy, concerning both their linguistic structure and their socio-political status as national vernaculars. DeCamp (1971) was among the first to point to the problem of defining the boundaries of the language varieties in such situations, where there is a continuous spectrum of speech varieties ranging from the creole to the standard. Caribbean linguists, however, have argued that there are sound linguistic grounds for treating the more "radical" creole varieties as autonomous. A large part of the debate over the socio-political status of the creoles has focused on situations such as those in Belize, Guyana, and Jamaica, where the creole is quite distant from the standard. There is a growing trend, among both the public and the political establishment, to view the creoles in these communities as languages distinct from English. For instance, Beckford-Wassink (1999: 66) found that 90 percent of informants in a language attitude survey regarded Jamaican Creole as a distinct language, basing their judgments primarily on lexicon and accent.

In intermediate creole situations such as in the Bahamas, Barbados, and Trinidad, there is a greater tendency to see the creole vernaculars as deviant dialects of English rather than separate varieties. Even here, though, there is a trend toward tolerating the use of these varieties for purposes of teaching the standard. So far, however, support for this comes primarily from linguists or other academics, and is not generally matched by popular opinion.

このような地域ごとの温度差は,共時的には言語学的な問題であり,社会言語学的な問題でもあるが,通時的にはクレオール変種が生じ,受け入れられ,標準変種との相対的な位置取りに腐心してきた経緯の違いに存する歴史言語学的な問題である.

・ Winford, Donald. "English in the Caribbean." Chapter 41 of A Companion to the History of the English Language. Ed. Haruko Momma and Michael Matto. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2008. 413--22.

2014-06-25 Wed

■ #1885. AAVE の文法的特徴と起源を巡る問題 [aave][creole][pidgin][sociolinguistics][ame][caribbean][syntax][be][aspect][inflection][3sp][variety][existential_sentence]

「#1841. AAVE の起源と founder principle」 ([2014-05-12-1]) と「#1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s」 ([2014-05-21-1]) で取り上げたが,AAVE (African American Vernacular English) とはアメリカ英語の1変種としてのいわゆる黒人英語 (Black English) を指す."Black" よりも "African-American" の呼称がふさわしいのは肌の色よりも歴史的な起源に焦点を当てるほうが適切であるから,"Vernacular English" の呼称がふさわしいのは,標準英語 (Standard English) に対して非標準英語 (Non-Standard English or Substandard English) と呼ぶのはいたずらに優劣が含意されてしまうからである.言語学的には AAVE という名称が定着している.

AAVE には,文法項目に限っても,標準英語に見られない特徴が多く認められる.全体としては,(主として白人によって話される)アメリカ南部方言や,カリブ海沿岸の英語を基とするクレオール諸語と近い特徴を示すといわれる.一方,イギリス諸方言に起源をもつと考えるのがより妥当な文法項目もある.具体的には以下に示すが,概ねこのような事情から,AAVE の文法的特徴とその起源を巡って2つの説が対立している.現在,アメリカ英語の変種に関する論争としては,最大の注目を集めている話題の1つといってよい.

1つ目の仮説は Creolist Hypothesis と呼ばれる.英語と西アフリカの諸言語とが混交した結果として生まれたクレオール語,あるいはそこから派生した英語変種が,AAVE の起源であるという説だ.これが後に標準英語との接触を保つなかで,徐々に標準英語へと近づいてきた,つまり脱クレオール化 (decreolization) してきたと考えられている.この説によると,アメリカ南部方言が AAVE と類似しているのは,後者が前者に影響を与えたからだと論じられる.AAVE に特徴的な語彙項目のなかには,voodoo (ブードゥー教), pinto (棺), goober (ピーナッツ)など西アフリカ諸語に由来するものも多く,この仮説への追い風となっている.

2つ目の仮説は Anglicist Hypothesis と呼ばれる.AAVE の特徴の起源はイギリス諸島からもたらされた英語諸変種にあるという説である.アメリカで黒人変種と白人変種が異なるのは,300年にわたる歴史のなかでそれぞれが独自の言語変化を遂げたからであり,かつ両変種の相互の接触が比較的少なかったからである.奴隷制の廃止後に南部の黒人が北部へ移民したあと,北部の都市では黒人変種と白人変種との差異が際だって意識され,それぞれ民族変種としてとらえられるようになった.

このように2つの仮説は鋭く対立しているが,起源を巡る論争で注目を浴びている AAVE の主たる文法的特徴を7点挙げよう.

(1) 3単現の -s の欠如.AAVE 話者の多くは,he go, it come, she like など -s のない形態を使用する.英語を基とするピジン語やクレオール語に同じ現象がみられるという点では Creolist Hypothesis に有利だが,一方でイングランドの East Anglia 方言でも同じ特徴がみられるという点では Anglicist Hypothesis にも見込みがある.関連して「#1850. AAVE における動詞現在形の -s」 ([2014-05-21-1]) も参照.

(2) 現在形における連結詞 (copula) の be の欠如.She real nice. They out there. He not American. If you good, you going to heaven. のような構文.連結詞の省略は,多くの言語でみられるが,とりわけカリブ海のクレオール語に典型的であるという点が Creolist Hypothesis の主張点である.イギリス諸方言には一切みられない特徴であり,この点では Anglicist Hypothesis は支持されない.

(3) 不変の be.標準変種のように,is, am, are などと人称変化せず,常に定形 be をとる.He usually be around. Sometime she be fighting. Sometime when they do it, most of the problems always be wrong. She be nice and happy. They sometimes be incomplete. など.(2) の連結詞の be の欠如と矛盾するようにもみえるが,be が用いられるのは習慣相 (habitual aspect) を表わすときであり,be 欠如の非習慣相とは対立する.不変の be 自体は他の英語変種にもみられるが,それが習慣相を担っているというのは AAVE に特有である.He busy right now. と Sometime he be busy. は相に関して文法的に対立しており,この対立を標準英語で表現するならば,He's busy right now. と Sometimes he's busy. のように副詞(句)を用いざるをえない.クレオール語では時制 (tense) よりも相 (aspect) を文法カテゴリーとして優先させることが多いため,不変の be は Creolist Hypothesis にとって有利な材料といわれる.相についていえば,AAVE では,ほかにも標準英語的な I have talked. I had talked. といった相に加え,完了を明示する I done talked. や遠過去を明示する I been talked. のような相もみられる.

(4) 等位節の2つ目の構造において助動詞のみを省略する傾向.標準英語では We were eating --- and drinking too. のように2つ目の節では we are をまるごと省略するのが普通だが,AAVE では多くのクレオール語と同様に are だけを省略し,We was eatin' --- an' we drinkin', too. とするのが普通である.

(5) 間接疑問文における主語と動詞の倒置.I asked Mary where did she go. や I want to know did he come last night. など.

(6) 存在文 (existential_sentence) に there ではなく it を用いる.It's a boy in my class name Joey. や It ain't no heaven for you to go to. など.

(7) 否定助動詞の前置.平叙文として平叙文のイントネーションで,Doesn't nobody know that it's a God. Cant't nobody do nothing about it. Wasn't nothing wrong with that. など.

1980年代までの学界においては Creolist Hypothesis が優勢だった.しかし,新たな事実が知られるようになるにつれ,すべてが Creolist Hypothesis で解決できるわけではないことが明らかになってきた.例えば,初期の AAVE を携えてアメリカ国外へ移住した集団の末裔が Nova Scotia (Canada) や Samaná (Dominican Republic) で現在も話している変種は,その初期の AAVE の特徴を多く保存していることが予想されるが,不変の be などの決定的な特徴を欠いている.これは,問題の AAVE 的な特徴が,AAVE の初期から備わっていたものではなく,比較的新しく獲得されたものではないかという新説を生み出した.

また,do を otherwise として用いる語法が AAVE にあるが,イングランドの East Anglia 方言にも同じ語法があり,これが起源であると考えざるをえない.AAVE の Dat's a thing dat's got to be handled just so, do it'll kill you. と East Anglia 方言の You lot must have moved it, do I wouldn't have fell in. を比較されたい.

現段階で妥当と思われる考え方は,Creolist Hypothesis と Anglicist Hypothesis は全面的に対立する仮説ではなく,組み合わせてとらえるべきだということである.それぞれの仮説によってしか合理的に説明されない特徴もあれば,両者ともに説明原理となりうるような特徴もある.また,いずれの説明も実際には関与していないような特徴もあるかもしれない.単純な二者択一に帰してしまうことは,むしろ問題だろう.

以上,Trudgill (51--60) を参照して執筆した.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

2014-05-12 Mon

■ #1841. AAVE の起源と founder principle [aave][creole][sociolinguistics][caribbean][dialect][founder_principle]

アメリカのいわゆる黒人英語と呼ばれている英語変種は,学術的には African American Vernacular English (AAVE) と呼ばれている.AAVE の起源を巡ってはクレオール語起源説 (creolist hypothesis) とイギリス変種起源説 (Anglicist hypothesis) が鋭く対立しており,アメリカ英語に関する一大論争となっている.穏健派の間では両仮説を組み合わせた折衷的な見解が支持を得ているようだが,議論の決着は着いていないといってよい.AAVE とその起源を巡る論争の概要については,Trudgill (51--60) 辺りを参照されたい.また,Language Varieties の African American Vernacular English も参考までに.

昨日の記事「#1840. スペイン語ベースのクレオール語が極端に少ないのはなぜか」 ([2014-05-11-1]) で,植民地における homestead stage と plantation stage の区別が言語のクレオール化の可能性と相関しているという仮説を紹介した.この仮説は,AAVE が英語とアフリカ諸語とが混成したクレオール語に由来したとする creolist hypothesis と関わりをもち,Mufwene, Salikolo S. (The Ecology of Language Evolution. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.) がこの観点から論を展開している.Mufwene は,複数の言語変種が行われている植民地社会においては,最初の植民者たち (founders) ,正確にいえば最初の影響力のある植民者の集団の変種が優勢となるという founder principle を唱えた.ここで "founders" とは,新社会の中心にあってオピニオン・リーダーとして機能し,たとえ少数派となっても影響力を保持するとされる集団である.

さて,植民史の homestead stage においては,founders とはヨーロッパ語の標準変種を話す白人たちであり,plantation stage においては,白人からヨーロッパ語を学んだ非標準変種を話す監督係の黒人たちである.founder principle によれば,前者の段階が長ければ長いほどクレオール化は抑制され,逆に後者の段階が長ければ長いほどクレオール化が促進されることになる.この観点から,caribbean の各記事で話題にしてきたように,カリブ海地域では軒並み英語ベースのクレオール語が発生した一方で,北米本土ではAAVEを含めた英語諸変種においてクレオール的な要素が比較的薄いことは注目に値する.というのは,実際にカリブ海地域では plantation stage が長かったのに対して,北米本土では homestead stage が長かったからだ.Millar (166) は,Mufwene の議論を概説した文章で,次のように述べている.

Returning to African American Vernacular English, Mufwene essentially suggests that the plantation environments so crucial to the development of English creoles in the Caribbean were a relatively late feature in the history of African settlement in North America. On plantations, speakers of mainstream Englishes rarely interacted regularly with the slave population, meaning that new varieties of a creole type could develop unchecked. But for a large part of the seventeenth century (and into the eighteenth century in many places), African slaves in North America did not live on large plantations, growing cotton, tobacco or rice, depending on where the plantation was situated. Instead, most lived in much close proximity to their owners and, crucially, indentured servants, essentially temporary slaves of European --- normally English-speaking --- origin, on a much smaller farm. While there might be a number of slaves on the larger farms, the numerical preponderance of Africans associated with later plantations was nowhere in evidence. Mufwene terms this period the homestead stage.

This close proximity did not necessarily make the slaves' lives easier than they were later, but it did make it possible for Africans to learn the dominant language directly and continuously from native speakers in a way which fundamentally differs from the situation in which Africans found themselves in the large Caribbean plantations, where mainstream varieties of English were normally in short supply. It is likely, of course, that the primary influence on the evolving English of Africans during this period was not the language of the prosperous but rather of those with whom they had most contact; in particular, perhaps, the English of the indentured servants.

founder principle は,クレオール化のみならず,方言接触に関する話題にも関わる仮説としても期待できそうだ.方言接触については「#1671. dialect contact, dialect mixture, dialect levelling, koineization」 ([2013-11-23-1]) を参照.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-01-22 Wed

■ #1731. English as a Basal Language [model_of_englishes][sociolinguistics][caribbean][lingua_franca]

英語話者や英語圏をモデル化する試みについては,model_of_englishes の各記事で話題に取り上げてきた.とりわけ古典的な分類は ENL, ESL, EFL と3区分するやり方だが,ここにもう1つ EBL (English as a Basal Language) を加えるべきだとの注目すべき見解がある.「#1713. 中米の英語圏,Bay Islands」 ([2014-01-04-1]) と「#1714. 中米の英語圏,Bluefields と Puerto Limon」 ([2014-01-05-1]) で参照した Lipski の論文を読んでいるときに出会った見解だ.Lipski (204) は,次のように述べている.

In offering a classification of societies where English is used, Moag suggests, in addition to the usual English as a native/second/foreign language, a new category: English as a Basal Language, defined for a society in which "English is the mother tongue of a minority group of a larger populace whose native tongue, often Spanish, is clearly the dominant language of the society as a whole." . . . . Moag's typology is undoubtedly useful and underlines the necessity for expanding the currently accepted typologies to accommodate such situations as the CAmE groups.

そこで,引用されている Moag の論文に当たってみた.Moag (14) によると,EBL として指示される地域には次のようなものがあるという.Argentina, Costa Rica (Jamaican Blacks), Dominican Republic (Samaná), Honduras (Coast and Bay Islands), Mexico (Mormon Colonístas), Nicaragua (Meskito Coast), Panama, San Andres (Columbia), St. Maarten (Netherlands Antilles) .

EBL の最大の特徴は,引用中に定義にもあるとおり,少数派としての英語母語使用にある.少数派の英語母語話者共同体が多数派のスペイン語母語話者共同体に隣接して暮らしているという構図だ.従来のモデルでは,このような社会言語学的状況におかれた英語変種を適切に位置づけることができなかった.というのは,従来の3区分では,英語は常に社会的に権威ある言語であるという前提が暗に含まれていたからだ.ENL では,当然ながら英語母語話者が多数派なので,英語の社会的な安定感は確保されている.ESL や EFL でも,国内的,国際的な lingua franca としての英語の役割は概ねポジティヴに評価されている(植民地主義への反感などによる例外はあるが,Moag (36) にあるように,多くの場合は一時的なものであると考えられる).ところが,上記の地域では,英語は少数派言語として多数派言語によって周縁に追いやられており,さらにはその母語話者によってすらネガティヴな評価を与えられているのである(母語話者によるネガティヴな評価は,その英語変種が標準的な変種というよりはクレオール化した変種であるという点にしばしば帰せられる).

英語が(母語話者によってすら)負の評価を与えられているという社会言語学的状況は,ぜひともモデルのなかに含める必要があるだろう.かくして,ENL, ESL, EFL, EBL の4区分という新モデルが提案されることとなった.Moag (12--13) では,この4種類を区別するのに26の細かな判断基準を設けている.ただし,Moag の論文は30年以上も前のものなので,「EBL 地域」の最新の言語事情が知りたいところではある.

・ Lipski, John M. "English-Spanish Contact in the United States and Central America: Sociolinguistic Mirror Images?" Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 191--208.

・ Moag, Rodney. "English as a Foreign, Second, Native and Basal Language." New Englishes. Ed. John Pride. Rowley, Mass.: Newbury House, 1982. 11--50.

2014-01-05 Sun

■ #1714. 中米の英語圏,Bluefields と Puerto Limon [history][caribbean][map]

昨日の記事「#1713. 中米の英語圏,Bay Islands」 ([2014-01-04-1]) に引き続き,中米における英語圏について.今日は,Bluefields (Nicaragua) と Puerto Limón (Costa Rica) の英語事情に注目したい.

Nicaragua のカリブ海に面した港町 Bluefields は,British West Indian, Nicaraguan ladino, Miskito (Afro-Indian) の人々を混合させた多文化の地である.アフリカ系ヨーロッパ人は英語を母語として話し,それ以外は程度の差はあれスペイン語を話す.Nicaragua のカリブ海岸は19世紀半ばまでイギリスの支配下にあり,同種の周辺地域と同様に,英領西インド諸島を経由してやってきたアフリカ人やヨーロッパ人が住みつくことが多かった.現在,その子孫たちが英語を話していることになる.Bluefields の英語話者集団は,昨日の Bay Islands の英語話者集団と同様に,スペインを話す国内の多数派集団とよりも,周辺諸国の英語圏諸地域との連携のほうが強い(以上,Lipski, pp. 194--95 より).

次に,Costa Rica のカリブ海岸に面する Puerto Limón に話を移そう.「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]) や「#1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散」 ([2014-01-02-1]) の年表で示したが,Puerto Limón の英語使用の歴史は,Bay Islands や Bluefields に比べて遅めである.この町の英語話者の先祖は,1871年以降に鉄道建設のために Jamaica などから連れてこられた大量の黒人労働者である.彼ら労働者たちは,一般の Costa Rica 国民からは隔離され,その後も現在に至るまで融合したとは言いがたい.Puerto Limón の英語話者比率は,Bay Islands や Bluefiedls に比べて低いが,英語による教育の機会などは与えられている(以上,Lipski, pp. 195--96 より).

昨日と今日の記事で Bay Islands, Bluefields, Puerto Limón など一般には知られていない中米の英語圏を話題にしたのは,母語としての英語が社会の少数派によって話されている地域が,現代世界に存在するという事実に注意を向けたかったからである.上記のいずれの地でも,英語の社会的な立場は,威信のある周囲の多数派言語であるスペイン語の圧力により,相対的に低い.一般的には英語は現代世界において威信のある言語であるということはできるかもしれないが,例外なくどこでもそうであるわけではない,という点は認識しておく必要がある.

・ Lipski, John M. "English-Spanish Contact in the United States and Central America: Sociolinguistic Mirror Images?" Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 191--208.

2014-01-04 Sat

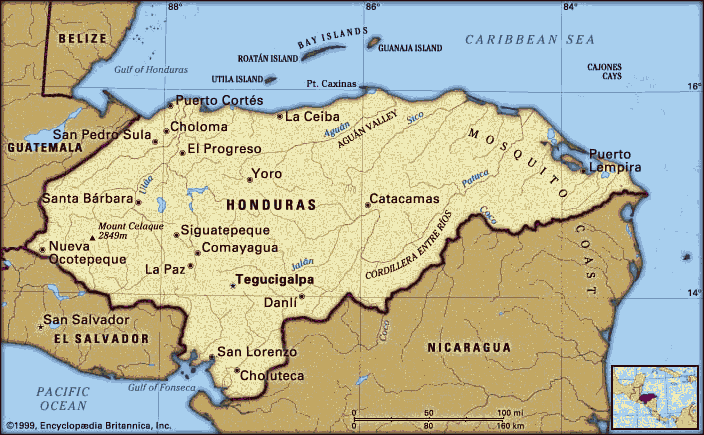

■ #1713. 中米の英語圏,Bay Islands [history][caribbean][map]

中南米は植民史により英語ではなくスペイン語やポルトガル語が優勢の地域ではあるが,カリブ海に臨む中米諸国には英語が母語として話されている地域が点在している.これは,19世紀半ば,英植民地における奴隷制廃止に伴って生じた経済危機を受けて,地域の人口が移動したことに由来する.現在,公用語として英語を採用している Belize のほかにも,Bay Islands (Honduras), Bluefields を主とするカリブ海岸地域や Corn Islands (Nicaragua), Puerto Limón (Costa Rica), Livingston や Puerto Barrios (Guatemala),San Andrés と Providencia (Columbia),Bocas del Toro や Colón (Panama) などにおいて,英語が母語として話されている.今回は,Honduras の例を見てみよう.

Honduras 北東岸は Costa de Mosquitos と呼ばれており,人口は多くないが英語ベースのクレオール語を話すインディアン民族が住んでいる.北岸地域は La Costa Norte と呼ばれており,クレオール英語を話す黒人を含むいくつかの少数民族が住んでいる.その沖合に浮かぶ Islas de la Bahía (Bay Islands) では,1830年代にカリブ海の Cayman Islands から移民してきた人々の子孫が住んでおり,近年は本土からのスペイン語話者も移住してきているものの,英語が主たる母語として話されている(「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]) 及び「#1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散」 ([2014-01-02-1]) の移民年表を参照).アメリカからの観光客にも人気が高い.

歴史的には Bay Islands は17世紀より海賊の温床であった.所有者を何度も変えてきたが,実質的に外から支配されることはなかったといってよい.現在,島民の大多数が黒人も白人も英語を母語として話しており,スペイン語の知識はあまりない.彼らは,島外に出るときには,本土を訪れるというよりもアメリカや西インド諸島の英語圏 (特に先祖の出身地である Jamaica や Cayman Islands)を訪れることのほうが多く,ホンジュラス本土との関係は比較的うすい.ただし,上記の現状は1986年の Lipski (193--94) に依拠したものなので,すでに古い情報になっているかもしれないことを断っておきたい.

・ Lipski, John M. "English-Spanish Contact in the United States and Central America: Sociolinguistic Mirror Images?" Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 191--208.

2014-01-02 Thu

■ #1711. カリブ海地域の英語の拡散 [geography][geolinguistics][history][timeline][caribbean]

カリブ海の英語の分布について,「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]),「#1680. The West Indies の言語事情」 ([2013-12-02-1]),「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]) で取り上げてきた.この地域の言語事情は実に複雑であり,主として社会言語学的な関心から "Caribbean linguistics" という名で研究が進められている.

英語事情をとってみても,移民の歴史,英語が拡散した歴史,pidgin や creole と標準英語の社会言語学的な関係,スペイン語など他の主要言語との共存など,問うべき課題は多い.問題の多様さと複雑さの背景には,歴史自体の多様さと複雑さがあるのだが,Holm (1) は3点を指摘している.その主旨を示すと,(1) この地域の英語の歴史は,個々の島や領土ごとの複数の英語史から成っており,1つの歴史にまとめることが難しい,(2) この地域の英語の拡散史は,イギリスの政治的権力の拡散史とは必ずしも一致していない,(3) この地域の伝統的な歴史記述は,政治史や経済史が主であり,言語史は pidgin や creole に付されていた否定的な評価ゆえに顧みられることが少なかった.(3) については現在では事情は変わってきているのだろうが,(1) と (2) はいかんともしがたい.(2) についていえば,例えば St. Lucia や Dominica は旧英国植民地だが,現在英語は概して第2言語として話されるにすぎない.一方,旧英国植民地ではないコスタリカの Puerto Limón やドミニカ共和国の the Samaná Peninsula では,現在英語が母語として話されている,などの事情がある.

この地域の移民史と英語拡散史の一端を「#1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地」 ([2013-12-24-1]) の記事でみたが,島・領土ごとに情報をまとめた資料が Holm の補遺 (18--19) に与えられていたので,それを示しておきたい.約30年前の古い情報ではあるが,移民の出身地,Holm 執筆当時に得られた人口などがまとめられており,地域の英語事情の概観を得るのに参考にはなるだろう(表中の人口欄の「---」は,他の行に算入されていることを示す).

| Date of Settlement | Territory | Settled from | Current Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1609 | Bermuda (Atlantic) | Britain, Africa | 55,000 |

| 1624 | St. Kitts (Leewards) | Britain, Africa, Ireland | 40,000 |

| 1627 | Barbados | Britain, Africa, Ireland | 280,000 |

| 1628 | Nevis (Leewards) | St. Kitts, Ireland | 15,000 |

| 1628 | Barbuda (Leewards) | St. Kitts, Ireland | 1,100 |

| 1631 | St. Martin (Dutch Ww.) | Leewards, Holland, France | 10,000 |

| 1631 | Providence (West Car.) | Britain, Bermuda, New England | 4,000 |

| 1631? | San Andrés (West Car.) | uncertain | 4,000 |

| 1632 | Antigua (Leewards) | St. Kitts | 74,000 |

| 1633 | Montserrat (Leewards) | St. Kitts, Ireland | 12,000 |

| 1636 | St. Eustatius (D. Ww.) | Leewards, Holland | 1,000 |

| 1640 | Saba (Dutch Windwards) | St. Eustatius, Leewards | 1,000 |

| 1648 | Bahamas (Eleuthera) | Bermuda | 240,000 |

| 1650 | Anguilla (Leewards) | Leewards | 6,500 |

| 1651 | Suriname (S. America) | Barbados (Sranan 1st lang.: 125,000) | 404,000 |

| 1655 | Jamaica | Barbados, Leewards, Suriname, Bermuda | 2,215,000 |

| 1666 | British Virgin Is. | Leewards | 12,000 |

| 1670 | Cayman Is. (West Car.) | Britain, Jamaica | 16,000 |

| 1670 | Carolina | Britain, Jamaica, Barbados, Bermuda, Bahamas | Gullah: 250,000 |

| 1672 | St. Thomas (Virgin Is.) | Leewards, Dutch Windwards, Denmark | --- |

| 1678 | Turks and Caicos | Bermuda | 7,000 |

| 1684 | St. John (Virgin Is.) | St. Thomas | --- |

| to 1715 | Saramaccan (Suriname) | Coastal plantations | (20,000) |

| from 1715 | Djuka (Suriname) | Coastal plantations | (16,000) |

| ca. 1730 | Miskito Coast (C.A.) | Belize, Jamaica | 40,000 |

| 1733 | St. Croix (Virgin Is.) | Leewards, St. Thomas | --- |

| 1740's | (British) Guyana | Barbados, Leewards | 832,000 |

| from 1760 | Aluku (Fr. Guiana) | Coastal plantations of Suriname | --- |

| 1763 | Dominica (Br. Windw.) | French Antilles (French Creole) | |

| 1763 | St. Vincent (Br. Ww.) | Leewards, Barbados | 112,000 |

| 1763 | Grenada (Br. Windw.) | Fr. Antilles, Leewards, Barbados | 108,000 |

| 1763 | Tobago | ? | --- |

| from 1780 | southern Bahamas | U.S. South | --- |

| 1786 | Belize | Miskito Coast | 150,000 |

| 1786 | Andros, Bahamas | Miskito Coast | --- |

| 1797 | Trinidad | Windwards, Barbados, Bahamas | 1,150,000 |

| 1815 | St. Lucia | French Antilles (French Creole) | |

| from 1824 | Samaná, Dominican Rep. | U.S. freedmen | 8,000 |

| 1827 | Bocas del Toro, Panama | San Andrés | --- |

| 1830's | Bay Islands, Honduras | Cayman Islands | 10,000 |

| 1849 | Nacimiento, Mexico | Afro-Seminoles | 300? |

| from 1850 | Rama, east Nicaragua | Miskito Coast | 300? |

| 1870 | Bracketville, Texas | Nacimiento Afro-Seminoles | 300? |

| 1871 | Puerto Limón, Costa Rica | Jamaica, Eastern Caribbean | 40,000 |

| 1898 | Puerto Rico | United States | 100,000? |

| 1904--14 | Panama | Jamaica, Eastern Caribbean | 100,000? |

| 1917 | Virgin Islands | United States | total: 100,000 |

| total: 6,398,500 | |||

・ Holm, J. A. "The Spread of English in the Caribbean Area." Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 1--22.

2013-12-24 Tue

■ #1702. カリブ海地域への移民の出身地 [geography][geolinguistics][history][timeline][map][caribbean]

この4日間の記事 ##1698,1699,1700,1701 で,Gramley の英語史のコンパニオンサイトより,7章のための補足資料を参照しながら,英語圏の人々の移住とそれに伴う英語拡散の歴史を,目的地あるいは出身地により整理してきた.今日はこの一連の話題の最後として,同資料の pp. 7--8 より,カリブ海地域 (the Caribbean) への人々と英語の進出を整理したい.

| FROM | TO |

|---|---|

| 17th Century Movements | |

| Britain | Bermuda (1609); Providence Island (1631); Cayman Islands (1670) |

| Ireland | St. Kitts (1624); Barbados (1627); Nevis, Barbuda (1628) |

| Africa | Bermuda (1609) |

| Bermuda | Providence (1631); Bahamas (1648); Jamaica (1655); Turks + Caicos (1678) |

| New England | Providence (1631) |

| St. Kitts | Nevis, Barbuda (1628); Antigua (1632); Montserrat (1633) |

| The Leeward Islands | Anguilla (1650); Jamaica (1655); St. Thomas (1672) |

| Barbados | Suriname (1651); Jamaica (1655) |

| Suriname | Jamaica (1655) |

| Jamaica | Cayman Islands (1670) |

| St. Thomas | St. John (1684) |

| 18th Century Movements | |

| Belize | the Moskito Coast (1730) |

| Jamaica | the Moskito Coast (1730) |

| Leewards | St. Croix (1733); Guyana (1740s); St. Vincent, Grenada (1763) |

| St. Thomas | St. Croix (1733) |

| Barbados | Guyana (1740s); St. Vincent, Grenada (1763), Trinidad (1797) |

| American South | Bahamas (1780ff) |

| Moskito Coast | Belize, Andros, Bahamas (1786) |

| Windwards | Trinidad (1797) |

| 19th Century Movements | |

| US (freed slaves) | Samaná (Dominican Republic) (1824) |

| San Andrés | Cocas del Toro (Panama) (1827) |

| Cayman Islands | Bay Islands (Honduras) (1830s) |

| Jamaica | Puerto Limón (Costa Rica) (1871) |

| US | Puerto Rico (1898) |

| 20th Century Movements | |

| Jamaica | Panama (1904--1914) |

| US | the American Virgin Islands (1917) |

カリブ海地域は日本にとってあまり馴染みのない地域なので,地理関係もつかみにくいかもしれない.地域の地図は,「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]) を参照. *

外からの人口流入もさることながら,同地域内での人々の移動も頻繁だったことがよくわかる.例えば,Barbados, Belize, Bermuda, Cayman Islands, Jamaica, the Moskito Coast, St. Kitts, St. Thomas, Suriname の名前は,出発地にも目的地にも現れている.また,Jamaica 発で英語が広がった the Bay Islands (Honduras), the Corn Islands (Nicaragua), Blue Fields (Nicaragua), Puerto Limón (Costa Rica) や Belize など中米に属する英語圏の存在は忘れられがちだが,英語の拡散を扱う上では見逃せない.この地域の英語拡散の歴史についての詳細は,Holm を参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

・ Holm, J. A. "The Spread of English in the Caribbean Area." Focus on the Caribbean. Ed. M. Görlach and J. A. Holm. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1986. 1--22.

2013-12-23 Mon

■ #1701. アメリカへの移民の出身地 [geography][geolinguistics][history][timeline][caribbean]

「#1699. アメリカ発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-21-1]) の記事では,アメリカ「から」の人々の移住と英語の拡大の歴史を一覧したが,アメリカ「へ」の人口流入の歴史も,アメリカ英語の形成過程を論じる上では重要な知識である.アメリカ移民史は一大分野をなすが,英語史の話題として論じるにあたっては,簡便なリストが手元にあると重宝する.「#158. アメリカ英語の時代区分」 ([2009-10-02-1]) よりは詳しいが,本格的な移民史よりは簡略な表が,Gramley の英語史のコンパニオンサイトにあった.7章のための補足資料 (pp. 6--7) より再現しよう.一部,目的地として米国以外の地域も含まれている.

| FROM | TO |

|---|---|

| Southern England | Eastern New England, the coastal South (from the early 17th century) |

| The Caribbean | Virginia and the plantation South (from the early 17th century) |

| Northern England, Scotland, Ulster | Southeast Pennsylvania, the Piedmont, and the Appalachian South (all from the late 17th century) |

| Germany | Pennsylvania (from the late 17th century) |

| The 13 colonies | Upper Canada, the Maritimes (in the late 18th century) |

| Haiti | Louisiana (in the late 18th century) |

| New England | Northwest Territory (from the early 19th century) |

| Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, and the Carolinas, and Georgia | the Ohio Valley and Southern Appalachians (from the 18th century) |

| US (freed slaves) | Liberia (from 1822) |

| Upper Canada | the Prairie and Mountain provinces; British Columbia (19th century) |

| Midwest | the Oregon Territory, California, and the Mountain West (19th century) |

| New England | Hawaii (late 19th century) |

| Far West | Alaska (late 19th century) |

| US (colonial administration) | Philippines (from 1898--1946) |

上掲は,主としてアメリカが目的地となる移住についての表だが,部分的にアメリカが出発地となる移住の情報とも読める.移民はアメリカへ移動し,アメリカ内を移動し,アメリカから移動しているのである.その意味では,「#1698. アメリカからの英語の拡散とその一般的なパターン」 ([2013-12-20-1]) の略図も参考になるだろう.

上の年表によれば,アメリカ英語の形成と拡散の歴史は,17世紀初頭に始まり20世紀半ばまで続いたことが示唆されるが,その後もアメリカ(英語)が現在にいたるまで世界各地に影響力を行使し続けていることを考えれば,広い意味でのアメリカ英語の拡散史は約400年に及ぶことになる.対応するイギリス英語の拡散史は450年余なので,近現代における英語の世界展開の歴史に限定するのであれば,アメリカ英語にも充分に長い歴史があるということになろう.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2013-12-22 Sun

■ #1700. イギリス発の英語の拡散の年表 [bre][geography][geolinguistics][history][timeline][caribbean]

昨日の記事「#1699. アメリカ発の英語の拡散の年表」 ([2013-12-21-1]) を受けて,今日はイギリス版を.昨日と同様,Gramley の英語史のコンパニオンサイトより,7章のための補足資料の p. 6 を転載する.イギリス諸島のどの地域から,世界のどの地域へ人々と英語が移動したかを時代順に示したものである.

| FROM | TO |

|---|---|

| Southwest England | Southeastern Ireland (from 1556 to well into the 17th century) |

| Scotland + England | Ulster (from 1606 to the 1690's) |

| England + Scotland | North America (from 1607) |

| Britain + Ireland | the Caribbean (esp. Barbados) (from 1627) |

| Britain + Ireland | Australia (from 1788) |

| England | South Africa (from 1820) |

| Britain + Australia | New Zealand (from 1820) |

| Britain (exploration, trade, colonial administration) | West Africa: Gambia (1661, 1816); Sierra Leone (1787); Ghana (1824; 1850); Nigeria (1851, 1861); Camero on (1914) |

| East Africa: Uganda (1860's); Malawi (1878); Kenya (1886); Tanzania (1880's) | |

| Southern Africa: South Africa (1795); Botswana (19th century); Namibia (1878); Zambia (1888); Zimbabwe (1890); Swaziland (1894) | |

| South Asia: India (1600); Bangla Desh (1690); Sri Lanka (1796); Pakistan (1857) | |

| Southeast Asia: Malaysia (1786); Singapore (1819); Hong Kong (1841) |

この表をじっくり眺めれば,いかにイギリスが16世紀半ばから19世紀半ばまでの約300年間にわたって,ゆっくりと確実に英語の種を世界中に蒔いてきたかが分かるだろう.もちろん19世紀半ば以降もイギリスによる世界各地の統治は続いたし,現在でもその遺産は「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1]) として生きているので,広い意味でのイギリス英語の拡散は優に450年を超える歴史を有しているといえよう.

関連する年表や地域リストについては,「#1368. Fennell 版,英語史略年表」 ([2013-01-24-1]),「#1377. Gelderen 版,英語史略年表」 ([2013-02-02-1]),「#215. ENS, ESL 地域の英語化した年代」 ([2009-11-28-1]) も参照.

・ Gramley, Stephan. The History of English: An Introduction. Abingdon: Routledge, 2012.

2013-12-02 Mon

■ #1680. The West Indies の言語事情 [geography][creole][world_languages][diglossia][sociolinguistics][language_shift][caribbean]

昨日の記事「#1679. The West Indies の英語圏」 ([2013-12-01-1]) で示唆したように,西インド諸島の言語事情は,歴史的な事情で複雑である.近代における列強の領土分割により,島ごとに支配的な言語が異なるという状況が生じ,島嶼間の地域的な連携も希薄となっている.独立国家と英米仏蘭の自治領とが混在していることも,地域の一体性が保たれにくい要因となっている.全体として,各地域では旧宗主国の言語が支配的だが,そのほかに主として英語やフランス語をベースとしたクレオール諸語(「#1531. pidgin と creole の地理分布」 ([2013-07-06-1])),移民の言語も行われており,言語事情は込み入っている.以下,Encylopædia Britannica 1997 の記事を参照してまとめる.

クレオール語についていえば,Jamaica における英語ベースのクレオール語がよく知られている.Jamaica では,ラジオ放送,小説,詩,劇などでクレオール語が広く使用されており,しばしば標準英語は不在である.場の雰囲気により,クレオール語と標準英語とのはざまで切り替えが生じることも通常である(Jamaican creole の具体例については,Jamaican Creole Texts を参照されたい).Jamaica に限らず,脱植民地化を経た the Commonwealth Caribbean でも,一般に英語ベースのクレオール語が重要性を増している.

フランス語ベースのクレオール語使用については,Haiti が典型例として挙げられる.Jamaica の場合と同様に,Haiti でもクレオール語が広範に使用されており,実際に大多数の国民が標準フランス語を理解しない.「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1]) で Haiti における diglossia について触れたように,クレオール語は,上位変種の標準フランス語に対して下位変種として位置づけられるものの,実用性の度合いでいえばむしろ優勢である.一方,Guadeloupe や Martinique の仏領アンティル諸島では,フランス本国の政治体制に組み込まれているために,標準フランス語の使用が一般的である.

スペイン語ベースのクレオール語は,Cuba, Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic などの主要なスペイン地域においては発達しなかった.ただし,Aruba, Curaçao, Bonaire など蘭領アンティル諸島では Papiamento と呼ばれる西・蘭・葡・英語の混成クレオール語が広く話されている.Puerto Rico では,帰国移民により,アメリカ英語の影響を受けたスペイン語が話されている.

移民の言語としては Hindi, Urdu, Chinese が行われている.奴隷制廃止後に,契約移民としてインドや中国からこの地域にやってきた人々の言語である.話者の多くは,それぞれの地域における支配的な言語へと徐々に同化していっている.例えば,Trinidad and Tobago では国民の4割がインド系移民だが,彼らの間で Hindi や Urdu の使用は少なくなってきているという.言語交替が進行中ということだろう.

2013-12-01 Sun

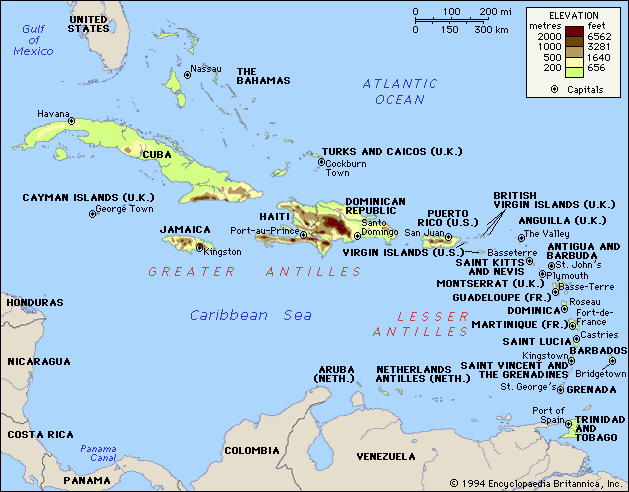

■ #1679. The West Indies の英語圏 [map][enl][creole][geography][caribbean]

The West Indies (西インド諸島)は,南北アメリカにはさまれ,大西洋からカリブ海およびメキシコ湾を隔てる大弧状列島を指す.名称はコロンブスが Indias と名付けたことに由来する.Greater Antilles, Lesser Antilles, Bahamas の諸島からなる.地域一帯は,ロッキー山脈とアンデス山脈をつなぐ火山帯の島嶼であること,植民地,プランテーション,奴隷制の歴史をもつことによって結びつけられている.現在13の独立国を含むが,その他は英・仏・米・蘭の領土である.

* *

* *

17--18世紀の西・仏・英・蘭・デンマークなどの列強による熾烈な領土分割の結果,地域内の連絡は弱くなった.各地域は言語的にも分割・個別化されており,英語圏,フランス語圏,オランダ語圏などの区別が明確である.現在も西インド諸島全体としての一体性はないが,歴史的・政治的な観点から4つの地域に分けるのが通例である.ハイチを含むヒスパニック系グループ,英領西インド諸島 (The British West Indies or the Commonwealth Caribbean; cf. 「#1676. The Commonwealth of Nations」 ([2013-11-28-1])),仏領アンティル諸島 (The French Antilles),蘭領アンティル諸島 (The Dutch Antilles) の4つだ.

とりわけ英語圏に注目しよう.歴史的な英領インド諸島は,Bahamas, Jamaica, Caymans, British Virgin Islands, Barbados, Trinidad, Tobago, Leeward Islands, Winward Islands から構成されていたが,1958年に大部分が Federation of West Indies (西インド諸島連邦)として独立し,その中から Bahamas, Barbados, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago などいくつかの地域が共和国として独立した.現在,西インド諸島でENL地域と呼べるのは以下の17地域である.

Anguilla, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Bermuda, the Cayman Islands, Dominica, Grenada, Jamaica, Montserrat, Saint Christopher and Nevis (St. Kitts-Nevis), Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, Trinidad and Tobago, the Turks and Caicos Islands, the Virgin Islands (US), the Virgin Islands (British)

周辺国を含むと,南米の Guyana や中米の Belize も公用語として英語を採用している.スペイン語やポルトガル語が支配的な中南米にあっては,珍しい2国である(ただし,Belize ではスペイン語も支配的).Guyana については,「#385. Guyanese Creole の連続体」 ([2010-05-17-1]) の記事も参照.

より一般的に世界の英語地域については,「#1591. Crystal による英語話者の人口」 ([2013-09-04-1]),「#177. ENL, ESL, EFL の地域のリスト」 ([2009-10-21-1]),「#215. ENS, ESL 地域の英語化した年代」 ([2009-11-28-1]) も参照.

また,同地域は世界有数のクレオール地域でもある.関連して,「#1531. pidgin と creole の地理分布」 ([2013-07-06-1]) も参照.

2013-07-06 Sat

■ #1531. pidgin と creole の地理分布 [pidgin][creole][map][geography][world_languages][tok_pisin][caribbean]

数え方にもよるが,世界中で100以上のピジン語やクレオール語が日常的に用いられているといわれる.なかには200万人を超える話者を擁する Tok Pisin のような活発な言語もある.実際,Tok Pisin は南太平洋における最大の言語である.英語を lexifier とする「#463. 英語ベースのピジン語とクレオール語の一覧」 ([2010-08-03-1]) についてはすでに本ブログで言及したが,かつての大英帝国の影響力から予想される通り,英語ベースのものが最も多い.

Romain (170--73) の地図を参照して lexifier 言語別にピジン語とクレオール語の個数を数え上げると,英語が35,フランス語が14,ポルトガル語が9,スペイン語が3,オランダ語が3,その他の言語が26となる. * *

世界に散在する種々のピジン語とクレオール語を分類するのに,上記のように語彙を提供している言語,すなわち superstratum の言語を基準とする方法があるが,ほかに地域を基準とする分類もある.地理的な分布の観点からピジン語やクレオール語を大きく2分すると,大西洋系列と太平洋系列とに分かれる.Romain (174--75) を引用しよう.

Creolists recognize two major groups of languages, the Atlantic and the Pacific, according to historical, geographic, and linguistic factors. The Atlantic group was established primarily during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries in the Caribbean and West Africa, while the Pacific group originated primarily in the nineteenth. The Atlantic creoles were largely products of the slave trade in West Africa which dispersed large numbers of West Africans to the Caribbean. Varieties of Caribbean creoles have also been transplanted to the United Kingdom by West Indian immigrants, as well as to the USA and Canada. The languages of the Atlantic share a West African common substrate and display many common features . . . . / In the Pacific different languages formed the substratum and socio-cultural conditions were somewhat different from those in the Atlantic. Although the plantation setting was crucial for the emergence of pidgins in both areas, in the Pacific laborers were recruited and indentured rather than slaves. Apart from Hawai'i, a history of more gradual creolization has distinguished the Pacific from the Atlantic (particularly Caribbean) creoles, whose transition has been more abrupt.

このように地理的な分布による2分法は明快だが,両系列のあいだに複雑な関係があることを見えにくくしているきらいがあることには注意しておきたい.例えば,両系列に共有されている語彙 (savvy "to know" や picanniny "child, baby") の存在は,2つの海をまたいで活躍した船乗りの役割を考慮せずにうまく説明することはできないだろう.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2010-06-10 Thu

■ #409. 植民地化の様式でみる World Englishes の分類 [history][variety][elf][model_of_englishes][caribbean]

現代世界で使用されている英語の変種をどのようにとらえ,どのように分類するかについては,これまでにも種々のモデルを紹介して考えてきた ( see model_of_englishes ).

今回は,ENL と ESL についてのみだが,イギリスによってどのように植民されたか,特にどのような人口構成で植民が行われたかに注目して英語変種の行われている地域を分類する方法を紹介する.Leith によると,イギリスによる植民地化には次の三つのタイプがあるという.

In the first type, exemplified by America and Australia, substantial settlement by first-language speakers of English displaced the precolonial population. In the second, typified by Nigeria, sparser colonial settlements maintained the precolonial population in subjection and allowed a proportion of them access to learning English as a second or additional language. There is yet a third type, exemplified by the Caribbean islands of Barbados and Jamaica. Here, a precolonial population was replaced by new labour from elsewhere, principally West Africa. (181--82)

この三分類は,イギリス出身植民者と先住民との関係という観点からの分け方で,理解しやすい.タイプ1は植民者がほぼ先住民を置き換えたという意味で displacement タイプと呼ぼう.タイプ2は,植民者は先住民を置き換えたのではなく,政治的に支配化におき,政治や教育などの制度 ( establishment ) を通じて英語を普及させたというタイプで,establishment タイプとでも呼べそうである.タイプ3は,植民者が西アフリカなどよその地域から労働力として奴隷を供給し,その奴隷たちが英語変種 ( pidgin や creole ) を習得して先住民とその言語を置き換えていったというタイプで,replacement タイプと呼べるかもしれない.

[2009-10-21-1]の (1a) のようにカリブ地域の英語国を指してアメリカやオーストラリアと同列に ENL 地域とみなす場合があるが,英語が根付くことになった歴史的経緯や人種の多様性を考慮したい文脈では,同列に並べるには違和感がある.このような場合に,イギリスによる植民地の設立と運営という観点からみた上記の三分類は役に立ちそうだ.

・ Leith, Dick. "English---Colonial to Post Colonial." Chapter 5 of English: History, Diversity and Change. Ed. David Graddol, Dick Leith and Joan Swann. London and New York: Routledge, 1996. 180--221.

2010-06-05 Sat

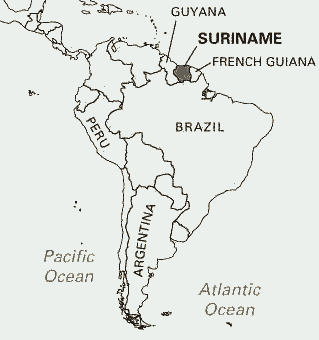

■ #404. Suriname の歴史と言語事情 [creole][map][caribbean]

南米のギアナ ( The Guianas ) は,他の南米の国々がスペイン語かポルトガル語を公用語とするのに対して,言語的には特異である.ギアナは西から順にガイアナ ( Guyana ),スリナム ( Suriname ),仏領ギアナ ( French Guiana ) の3地域からなるが,それぞれ植民地の歴史に応じて英語,オランダ語,フランス語が公用語となっている.ガイアナについては[2010-05-17-1]の記事で南米唯一の英語国として紹介し,そのピジン語 ( pidgin ) にも触れたが,今日はガイアナの東の隣国スリナムの歴史と言語事情を簡単に紹介したい.

スリナムは1995年に共和国として独立した旧オランダ植民地で,旧名はオランダ領土ギアナ ( Dutch Guiana ) といった.海岸部の低地はオランダの堤防・干拓技術により拓かれたオランダ風の町並みが見られ,現在でも経済的にオランダとの連携は強い.漁業は近年のスリナムの産業の一つで,海岸で穫れるエビは日本にも輸出されている.

公用語はオランダ語だが,もともとはイギリス植民地として出発した歴史を背景に,イギリスの奴隷貿易時代に端を発する英語ベースのクレオール語 ( creole ) がいくつか話されている.その中でも Sranan ( Sranantonga or Taki-Taki ) というクレオール語は民族をまたいで国民の95%以上に理解されるので,国内コミュニケーションの主要な媒体となっている.英語そのものも広く用いられている.

この地域へは1651年にイギリス人が入植していたが,第2次英蘭戦争の結果,1667年にオランダ領となった.代わりにイギリスへ割譲されたのが,アメリカの Nieuw Amsterdam (現在の New York City )である.後から思えば,この領土交換はオランダにとって最大の損失だったといえるだろう.17世紀のイギリスとオランダは,北海の漁業権,海上貿易・海運,植民地支配を巡って反目していたが,この英蘭戦争の後,オランダの威信は衰退していった.

オランダ領ギアナでは黒人奴隷によってタバコ,コーヒー,カカオ,サトウキビが栽培されていたが,1863年の奴隷廃止令に伴い,農業が不況となった.そこで契約労働者として多数のインド人が呼ばれた.また,同じオランダ領であったインドネシアのジャワからも移民が続々と押しかけ,米も栽培されるようになった.結果として,アジア的な雰囲気の色濃い文化と民族構成になっている.国民の 1/3 強がインド系,さらに 1/3 ほどが黒人クレオール系というから,"a fruit salad rather than a melting pot" と表現されるのもうなずける.こうした民族構成のなかで,オランダ語の影響をうけつつも数世紀をかけて発達してきた古い英語ベースのピジン語 Sranan が果たしている役割は大きい.Sranan の雰囲気を示すとこんな感じである.

Mi sa gi(bi) yu tin sensi ( I shall give you ten cents )

Ethnologue の記述も参照.

・ Svartvik, Jan and Geoffrey Leech. English: One Tongue, Many Voices. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 181--83.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow