2014-09-23 Tue

■ #1975. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (2) [grammaticalisation][unidirectionality][pragmatics][subjectification][invisible_hand][teleology][drift][reanalysis][iconicity][exaptation][terminology][toc]

昨日の記事「#1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1)」 ([2014-09-22-1]) を受けて,文法化 (grammaticalisation) 研究の守備範囲の広さについて補足する.Bussmann (196--97) によると,文法化がとりわけ関心をもつ疑問には次のようなものがある.

(a) Is the change of meaning that is inherent to grammaticalization a process of desemanticization, or is it rather a case (at least in the early stages of grammaticalization) of a semantic and pragmatic concentration?

(b) What productive parts do metaphors and metonyms play in grammaticalization?

(c) What role does pragmatics play in grammaticalization?

(d) Are there any universal principles for the direction of grammaticalization, and, if so, what are they? Suggestions for such 'directed' principles include: (i) increasing schematicization; (ii) increasing generalization; (iii) increasing speaker-related meaning; and (iv) increasing conceptual subjectivity.

昨日記した守備範囲と合わせて,文法化研究の潜在的なカバレッジの広さと波及効果の大きさを感じることができる.また,秋元 (vii) の目次より文法化理論に関連する用語を拾い出すだけでも,この分野が言語研究の根幹に関わる諸問題を含む大項目であることがわかるだろう.

第1章 文法化

1.1 序

1.2 文法化とそのメカニズム

1.2.1 語用論的推論 (Pragmatic inferencing)

1.2.2 漂白化 (Bleaching)

1.3 一方向性 (Unidirectionality)

1.3.1 一般化 (Generalization)

1.3.2 脱範疇化 (Decategorialization)

1.3.3 重層化 (Layering)

1.3.4 保持化 (Persistence)

1.3.5 分岐化 (Divergence)

1.3.6 特殊化 (Specialization)

1.3.7 再新化 (Renewal)

1.4 主観化 (Subjectification)

1.5 再分析 (Reanalysis)

1.6 クラインと文法化連鎖 (Grammaticalization chains)

1.7 文法化とアイコン性 (Iconicity)

1.8 文法化と外適応 (Exaptation)

1.9 文法化と「見えざる手」 (Invisible hand) 理論

1.10 文法化と「偏流」 (Drift) 論

文法化は,主として言語の通時態に焦点を当てているが,一方で主として共時的な認知文法 (cognitive grammar) や機能文法 (functional grammar) とも親和性があり,通時態と共時態の交差点に立っている.そこが,何よりも魅力である.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

・ 秋元 実治 『増補 文法化とイディオム化』 ひつじ書房,2014年.

2014-09-22 Mon

■ #1974. 文法化研究の発展と拡大 (1) [grammaticalisation][unidirectionality][productivity][construction_grammar][analogy][reanalysis][ot][contact][history_of_linguistics][teleology][discourse_marker][invited_inference]

「#1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か?」 ([2014-09-19-1]) の最後で何気なく提起したつもりだった問題に,「文法化を歴史的な流れ,drift の一種としてではなく,言語変化を駆動する共時的な力としてみることはできないのだろうか」というものがあった.少し調べてみると,文法化は付帯現象なのか,あるいはそれ自身が動力源なのかというこの問題は,実際,文法化の研究者の間でよく論じられている話題であることがわかった.今回は関連して文法化の研究を巡る動き,特にその扱う領域の発展と拡大について,Traugott の記述に依拠して概説したい.

文法化は,この30余年ほどをかけて言語学の大きなキーワードとして成長してきた.大きく考え方は2つある.1つは "reduction and increased dependency" とみる見方であり,もう1つはむしろ "the expansion of various kinds" とみる見方である.両者ともに,意味と音の変化が文法の変化と独立しつつも何らかの形で関わっているとみている,特に形態統語的な変化との関係をどうとらえるかによって立場が分かれている.

伝統的には,文法化は "reduction and increased dependency" とみられてきた.意味の漂白 (semantic bleaching) と音の減少 (reduction) がセットになって生じるという見方で,"unidirectionality from more to less complex structure, from more to less lexical, contentful status" (Traugott 273) という一方向性の原理を主張する.一方向性の原理は Givón の "Today's morphology is yesterday's syntax." の謂いに典型的に縮約されているが,さらに一般化した形で,次のような一方向性のモデルも提案されている.ここでは,自律性 (autonomy) を失い,他の要素への従属 (dependency) の度合いを増しながら,ついには消えてしまうという文法化のライフサイクルが表現されている.

discourse > syntax > morphology > morphphonemics > zero

ただし,一方向性の原理は,1990年代半ば以降,多くの批判にさらされることになった.原理ではなくあくまで付帯現象だとみる見方や確率論的な傾向にすぎないとする見方が提出され,それとともに「脱文法化」 (degrammaticalisation) や「語彙化」 (lexicalisation) などの対立概念も指摘されるようになった.しかし,再反論の一環として脱文法化とは何か,語彙化とは何かという問題も追究されるようになり,文法化をとりまく研究のフィールドは拡大していった.

文法化のもう1つの見方は,reduction ではなくむしろ expansion であるというものだ.初期の文法化研究で注目された事例は,たいてい屈折によって表現された時制,相,法性,格,数などに関するものだった.しかし,そこから目を移し,接続語や談話標識などに注目すると,文法化とはむしろ構造的な拡張であり適用範囲の拡大ではないかとも思われてくる.例えば,指示詞が定冠詞へと文法化することにより,固有名詞にも接続するようになり,適用範囲も増す結果となった.文法化が意味の一般化・抽象化であることを考えれば,その適用範囲が増すことは自然である.生産性 (productivity) の拡大と言い換えてもよいだろう.日本語の「ところで」の場所表現から談話標識への発達なども "reduction and increased dependency" とは捉えられず,むしろ autonomy を有しているとすら考えられる.ここにおいて,文法化は語用化 (pragmaticalisation) の過程とも結びつけられるようになった.

文法化の2つの見方を紹介したが,近年では文法化研究は新しい視点を加えて,さらなる発展と拡大を遂げている.例えば,1990年代の構文文法 (construction_grammar) の登場により,文法化の研究でも意味と形態のペアリングを意識した分析が施されるようになった.例えば,単数一致の A lot of fans is for sale. が複数一致の A lot of fans are for sale. へと変化し,さらに A lot of our problems are psychological. のような表現が現われてきたのをみると,文法化とともに統語上の異分析が生じたことがわかる.ほかに,give an answer や make a promise などの「軽い動詞+不定冠詞+行為名詞」の複合述部も,構文文法と文法化の観点から迫ることができるだろう.

文法化の引き金についても議論が盛んになってきた.語用論の方面からは,引き金として誘導推論 (invited inference) が指摘されている.また,類推 (analogy) や再分析 (reanalysis) のような古い概念に対しても,文法化の引き金,動機づけ,メカニズムという観点から,再解釈の試みがなされてきている.というのは,文法化とは異分析であるとも考えられ,異分析とは既存の構造との類推という支えなくしては生じ得ないものと考えられるからだ.ここで,類推のモデルとして普遍文法制約を仮定すると,最適性理論 (Optimality Theory) による分析とも親和性が生じてくる.言語接触の分野からは,文法化の借用という話題も扱われるようになってきた.

文法化の扱う問題の幅は限りなく拡がってきている.

・ Traugott, Elizabeth Closs. "Grammaticalization." Chapter 15 of Continuum Companion to Historical Linguistics. Ed. Silvia Luraghi and Vit Bubenik. London: Continuum, 2010. 271--85.

2014-09-20 Sat

■ #1972. Meillet の文法化 [grammaticalisation][unidirectionality][analogy][word_order]

昨日の記事「#1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か?」 ([2014-09-19-1]) 及び grammaticalisation の各記事で扱ってきた文法化は,1980年代以降,言研究において一躍注目を浴びるようになったテーマである.文法化の考え方自体は19世紀あるいはそれ以前より見られるが,「#417. 文法化とは?」 ([2010-06-18-1]) でも触れたように,最初に文法化という用語を用いて研究したのは Antoine Meillet (1866--1936) だといわれる.以下,Meillet の文法化の扱いについて3点触れておきたい.

まず,Meillet によれば,文法化とは "le passage d'un mot autonome au rôle d'élément grammatical" (131) である.挙げられている例は今となっては典型的なものばかりで,フランス語 pas の否定辞としての発達,英語でいえば have や be を用いた完了形など複合時制の発達,意志や義務を表わす動詞からの未来時制を表わす助動詞の発達などである.

なお,Meillet は,ラテン語では比較的自由だった語順がフランス語で SVO などの語順へと固定化を示した過程も一種の文法化ととらえている.英語史でいえば,古英語から中英語以降にかけての語順の固定化も,同様に文法化といえることになる.これらの言語では,古い段階でも語順は完全に自由だったわけではなく,談話的,文体的な要因により変異した.しかし,後に屈折の衰退と歩調を合わせて,語順が統語的,文法的な機能を帯びるようになったとき,Meillet はそこに文法化が起こっているとみたのである.複合時制の発達など前段落に挙げた例と語順の固定化という例が,同じ「文法化」という用語のもとで扱われるのはやや違和感があるかもしれないが,複数の語の組み合わせ方や順序が,当初の分析的な意味との関係から脱し,文法的な機能へと再解釈されていった点で,共通するところがある.

次に,Meillet が文法化について議論しているのは,文法形式の発展という文脈においてである.Meillet は,文法形式の発達には2種類あり,1つは類推 (analogy) ,1つは文法化であるとしている.前者については,vous dites ではなく *vous disez と誤用してしまうような過程が,場合によって一般化してしまうようなケースを念頭においている.このように類推は言語体系全体には大きな影響を与えない些末な発達だが,他方の文法化は新カテゴリーを創造し,言語体系全体に影響を与えるものとして区別している.

Tandis que l'analogie peut renouveler le détail des formes, mais laisse le plus souvent intact le plan d'ensemble du système existant, la «grammaticalisation» de certains mots crée des formes neuves, introduit des catégories qui n'avaient pas d'expression linguistique, transforme l'ensemble du système. (133)

最後に,文法化についてしばしば言及される方向性について,より具体的には分析から統合への方向性について,Meillet は次のような発言を残している.

Analyse et synthèse sont des termes logiques qui trompent entièrement sur les procès réels. La «synthèse» est une conséquence nécessaire et naturelle de l'usage qui est fait de groupes de mots. (147)

しかし,Meillet はここで唯一の方向性 (unidirectionality) について言及しているわけではないことに注意したい.pas の否定辞としての発達過程などは,むしろ,ne だけでは弱く感じられた否定を強調するために名詞 pas を加えたところが出発点となっているのであり,この付け加え自体は分析化の事例である.Meillet がこの点もしっかりと指摘していることは銘記しておきたい.

・ Meillet, Antoine. "L'évolution des formes grammaticales." Scientia 12 (1912). Rpt. in Linguistique historique et linguistique générale. Paris: Champion, 1958. 130--48.

2014-09-19 Fri

■ #1971. 文法化は歴史の付帯現象か? [drift][grammaticalisation][generative_grammar][syntax][auxiliary_verb][teleology][language_change][unidirectionality][causation][diachrony]

Lightfoot は,言語の歴史における 文法化 (grammaticalisation) は言語変化の原理あるいは説明でなく,結果の記述にすぎないとみている."Grammaticalisation, challenging as a phenomenon, is not an explanatory force" (106) と,にべもなく一蹴だ.文法化の一方向性を,"mystical" な drift (駆流)の方向性になぞらえて,その目的論 (teleology) 的な言語変化観を批判している.

Lightfoot は,一見したところ文法化とみられる言語変化も,共時的な "local cause" によって説明できるとし,その例として彼お得意の法助動詞化 (auxiliary_verb) の問題を取り上げている.本ブログでも「#1670. 法助動詞の発達と V-to-I movement」 ([2013-11-22-1]) や「#1406. 束となって急速に生じる文法変化」 ([2013-03-03-1]) で紹介した通り,Lightfoot は生成文法の枠組みで,子供の言語習得,UG (Universal Grammar),PLD (Primary Linguistic Data) の関数として,can や may など歴史的な動詞の法助動詞化を説明する.この「文法化」とみられる変化のそれぞれの段階において変化を駆動する local cause が存在することを指摘し,この変化が全体として mystical でもなければ teleological でもないことを示そうとした.非歴史的な立場から local cause を究明しようという Lightfoot の共時的な態度は,その口から発せられる主張を聞けば,Saussure よりも Chomsky よりも苛烈なもののように思える.そこには共時態至上主義の極致がある.

Time plays no role. St Augustine held that time comes from the future, which doesn't exist; the present has no duration and moves on to the past which no longer exists. Therefore there is no time, only eternity. Physicists take time to be 'quantum foam' and the orderly flow of events may really be as illusory as the flickering frames of a movie. Julian Barbour (2000) has argued that even the apparent sequence of the flickers is an illusion and that time is nothing more than a sort of cosmic parlor trick. So perhaps linguists are better off without time. (107)

So we take a synchronic approach to history. Historical change is a kind of finite-state Markov process: changes have only local causes and, if there is no local cause, there is no change, regardless of the state of the grammar or the language some time previously. . . . Under this synchronic approach to change, there are no principles of history; history is an epiphenomenon and time is immaterial. (121)

Lightfoot の方法論としての共時態至上主義の立場はわかる.また,local cause の究明が必要だという主張にも同意する.drift (駆流)と同様に,文法化も "mystical" な現象にとどまらせておくわけにはいかない以上,共時的な説明は是非とも必要である.しかし,Lightfoot の非歴史的な説明の提案は,例外はあるにせよ文法化の著しい傾向が多くの言語の歴史においてみられるという事実,そしてその理由については何も語ってくれない.もちろん Lightfoot は文法化は歴史の付帯現象にすぎないという立場であるから,語る必要もないと考えているのだろう.だが,文法化を歴史的な流れ,drift の一種としてではなく,言語変化を駆動する共時的な力としてみることはできないのだろうか.

・ Lightfoot, David. "Grammaticalisation: Cause or Effect." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 99--123.

2014-04-17 Thu

■ #1816. drift 再訪 [drift][gvs][germanic][synthesis_to_analysis][language_change][speed_of_change][unidirectionality][causation][functionalism]

Millar (111--13) が,英語史における古くて新しい問題,drift (駆流)を再訪している(本ブログ内の関連する記事は,cat:drift を参照).

Sapir の唱えた drift は,英語なら英語という1言語の歴史における言語変化の一定方向性を指すものだったが,後に drift の概念は拡張され,関連する複数の言語に共通してみられる言語変化の潮流をも指すようになった.これによって,英語の drift は相対化され,ゲルマン諸語にみられる drifts の比較,とりわけ drifts の速度の比較が問題とされるようになった.Millar (112) も,このゲルマン諸語という視点から,英語史における drift の問題を再訪している.

A number of scholars . . . take Sapir's ideas further, suggesting that drift can be employed to explain why related languages continue to act in a similar manner after they have ceased to be part of a dialect continuum. Thus it is striking . . . that a very similar series of sound changes --- the Great Vowel Shift --- took place in almost all West Germanic varieties in the late medieval and early modern periods. While some of the details of these changes differ from language to language, the general tendency for lower vowels to rise and high vowels to diphthongise is found in a range of languages --- English, Dutch and German --- where immediate influence along a geographical continuum is unlikely. Some linguists would suggest that there was a 'weakness' in these languages which was inherited from the ancestral variety and which, at the right point, was triggered by societal forces --- in this case, the rise of a lower middle class as a major economic and eventually political force in urbanising societies.

これを書いている Millar 自身が,最後の文の主語 "Some linguists" のなかの1人である.Samuels 流の機能主義的な観点に,社会言語学的な要因を考え合わせて,英語の drift を体現する個々の言語変化の原因を探ろうという立場だ.Sapir の drift = "mystical" というとらえ方を退け,できる限り合理的に説明しようとする立場でもある.私もこの立場に賛成であり,とりわけ社会言語学的な要因の "trigger" 機能に関心を寄せている.関連して,「#927. ゲルマン語の屈折の衰退と地政学」 ([2011-11-10-1]) や「#1224. 英語,デンマーク語,アフリカーンス語に共通してみられる言語接触の効果」 ([2012-09-02-1]) も参照されたい.

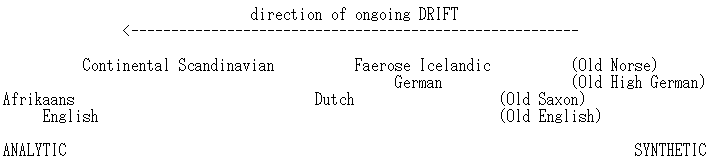

ゲルマン諸語の比較という点については,Millar (113) は,drift の進行の程度を模式的に示した図を与えている.以下に少し改変した図を示そう(かっこに囲まれた言語は,古い段階での言語を表わす).

この図は,「#191. 古英語,中英語,近代英語は互いにどれくらい異なるか」 ([2009-11-04-1]) で示した Lass によるゲルマン諸語の「古さ」 (archaism) の数直線を別の形で表わしたものとも解釈できる.その場合,drift の進行度と言語的な「モダンさ」が比例の関係にあるという読みになる.

この図では,English や Afrikaans が ANALYTIC の極に位置しているが,これは DRIFT が完了したということを意味するわけではない.現代英語でも,DRIFT の継続を感じさせる言語変化は進行中である.

・ Millar, Robert McColl. English Historical Sociolinguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2012.

2014-01-19 Sun

■ #1728. Jespersen の言語進歩観 [language_change][teleology][evolution][unidirectionality][drift][history_of_linguistics][artificial_language][language_myth]

英語史の授業で英語が経てきた言語変化を概説すると,「言語はどんどん便利な方向へ変化してきている」という反応を示す学生がことのほか多い.これは,「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) の (2) に挙げた「言語変化はより効率的な状態への緩慢な進歩である」と同じものであり,言語進歩観とでも呼ぶべきものかもしれない.しかし,その記事でも述べたとおり,言語変化は進歩でも堕落でもないというのが現代の言語学者の大方の見解である.ところが,かつては,著名な言語学者のなかにも,言語進歩観を公然と唱える者がいた.デンマークの英語学者 Otto Jespersen (1860--1943) もその1人である.

. . . in all those instances in which we are able to examine the history of any language for a sufficient length of time, we find that languages have a progressive tendency. But if languages progress towards greater perfection, it is not in a bee-line, nor are all the changes we witness to be considered steps in the right direction. The only thing I maintain is that the sum total of these changes, when we compare a remote period with the present time, shows a surplus of progressive over retrogressive or indifferent changes, so that the structure of modern languages is nearer perfection than that of ancient languages, if we take them as wholes instead of picking out at random some one or other more or less significant detail. And of course it must not be imagined that progress has been achieved through deliberate acts of men conscious that they were improving their mother-tongue. On the contrary, many a step in advance has at first been a slip or even a blunder, and, as in other fields of human activity, good results have only been won after a good deal of bungling and 'muddling along.' (326)

. . . we cannot be blind to the fact that modern languages as wholes are more practical than ancient ones, and that the latter present so many more anomalies and irregularities than our present-day languages that we may feel inclined, if not to apply to them Shakespeare's line, "Misshapen chaos of well-seeming forms," yet to think that the development has been from something nearer chaos to something nearer kosmos. (366)

Jespersen がどのようにして言語進歩観をもつに至ったのか.ムーナン (84--85) は,Jespersen が1928年に Novial という補助言語を作り出した背景を分析し,次のように評している(Novial については「#958. 19世紀後半から続々と出現した人工言語」 ([2011-12-11-1]) を参照).

彼がそこへたどり着いたのはほかの人の場合よりもいっそう,彼の論理好みのせいであり,また,彼のなかにもっとも古くから,もっとも深く根をおろしていた理論の一つのせいであった.その理論というのは,相互理解の効率を形態の経済性と比較してみればよい,という考えかたである.それにつづくのは,平均的には,任意の一言語についてみてもありとあらゆる言語についてみても,この点から見ると,正の向きの変化の総和が不の向きの総和より勝っているものだ,という考えかたである――そして彼は,もっとも普遍的に確認されていると称するそのような「進歩」の例として次のようなものを列挙している.すなわち,音楽的アクセントが次第に単純化すること,記号表現部〔能記〕の短縮,分析的つまり非屈折的構造の発達,統辞の自由化,アナロジーによる形態の規則化,語の具体的な色彩感を犠牲にした正確性と抽象性の増大である.(『言語の進歩,特に英語を照合して』) マルティネがみごとに見てとったことだが,今日のわれわれにはこの著者のなかにあるユートピア志向のしるしとも見えそうなこの特徴が,実は反対に,ドイツの比較文法によって広められていた神話に対する当時としては力いっぱいの戦いだったのだと考えて見ると,実に具体的に納得がいく.戦いの相手というのは,諸言語の完全な黄金時期はきまってそれらの前史時代の頂点に位置しており,それらの歴史はつねに形態と構造の頽廃史である,という神話だ.(「語の研究」)

つまり,Jespersen は,当時(そして少なからず現在も)はやっていた「言語変化は完全な状態からの緩慢な堕落である」とする言語堕落観に対抗して,言語進歩観を打ち出したということになる.言語学史的にも非常に明快な Jespersen 評ではないだろうか.

先にも述べたように,Jespersen 流の言語進歩観は,現在の言語学では一般的に受け入れられていない.これについて,「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) 及び「#1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」」 ([2013-02-07-1]) を参照.

・ Jespersen, Otto. Language: Its Nature, Development, and Origin. 1922. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ ジョルジュ・ムーナン著,佐藤 信夫訳 『二十世紀の言語学』 白水社,2001年.

2013-08-31 Sat

■ #1587. 印欧語史は言語のエントロピー増大傾向を裏付けているか? [drift][unidirectionality][synthesis_to_analysis][entropy][i-mutation][origin_of_language]

英語史のみならずゲルマン語史,さらには印欧語史の全体が,言語の単純化傾向を示しているように見える.ほとんどすべての印欧諸語で,性・数・格を始め種々の文法範疇の区分が時間とともに粗くなってきているし,形態・統語においては総合から分析へと言語類型が変化してきている.印欧語族に見られるこの駆流 (drift) については,「#656. "English is the most drifty Indo-European language."」 ([2011-02-12-1]) ほか drift の各記事で話題にしてきた.

しかし,この駆流を単純化と同一視してもよいのかという疑問は残る.むしろ印欧祖語は,文法範疇こそ細分化されてはいるが,その内部の体系は奇妙なほどに秩序正しかった.印欧祖語は,現在の印欧諸語と比べて,音韻形態的な不規則性は少ない.言語は時間とともに allomorphy を増してゆくという傾向がある.例えば i-mutation の歴史をみると,当初は音韻過程にすぎなかったものが,やがて音韻過程の脈絡を失い,純粋に形態的な過程となった.結果として,音韻変化を受けていない形態と受けた形態との allomorphy が生まれることになり,体系内の不規則性(エントロピー)が増大した([2011-08-13-1]の記事「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」を参照).さらに後になって,類推作用 (analogy) その他の過程により allomorphy が解消されるケースもあるが,原則として言語は時間とともにこの種のエントロピーが増大してゆくものと考えることができる.

だが,印欧語の歴史に明らかに見られると上述したエントロピーの増大傾向は,はたして額面通りに認めてしまってよいのだろうか.というのは,その出発点である印欧祖語はあくまで理論的に再建されたものにすぎないからである.もし再建者の頭のなかに言語はエントロピーの増大傾向を示すものだという仮説が先にあったとしたら,結果として再建される印欧祖語は,当然ながらそのような仮説に都合のよい形態音韻論をもった言語となるだろう.

実際に Comrie のような学者は,そのような仮説をもって印欧祖語をとらえている.Comrie (253) が想定しているのは,"an earlier stage of language, lacking at least many of the complexities of at least many present-day languages, but providing an explicit account of how these complexities could have arisen, by means of historically well-attested processes applied to this less complex earlier state" である.ここには,言語はもともと単純な体系として始まったが時間とともに複雑さを増してきたという前提がある.Comrie のこの前提は,次の箇所でも明確だ.

[I]t is unlikely that the first human language started off with the complexity of Insular Celtic morphophonemics or West Greenlandic morphology. Rather, such complexities arose as the result of the operation of attested processes --- such as the loss of conditioning of allophonic variation to give morphophonemic alternations or the grammaticalisation of lexical items to give grammatical suffixes --- upon an earlier system lacking such complexities, in which invariable words followed each other in order to build up the form corresponding to the desired semantic content, in an isolating language type lacking morphophonemic alternation. (250)

再建された祖語を根拠にして言語変化の傾向を追究することには慎重でなければならない.ましてや,先に傾向ありきで再建形を作り出し,かつ前提とすることは,さらに危ういことのように思える.Comrie (247) は印欧祖語再建に関して realist の立場([2011-09-06-1]) を明確にしているから,エントロピーが極小である言語の実在を信じているということになる.controversial な議論だろう.

・ Comrie, Barnard. "Reconstruction, Typology and Reality." Motives for Language Change. Ed. Raymond Hickey. Cambridge: CUP, 2003. 243--57.

2013-02-28 Thu

■ #1403. drift を合理的に説明する Ritt の試み [drift][teleology][unidirectionality][causation][language_change][functionalism]

昨日の記事「#1402. 英語が千年間,母音を強化し子音を弱化してきた理由」 ([2013-02-27-1]) で取り上げた論文で,Ritt は歴史言語学上の重要な問題である drift (駆流)にまとわりつく謎めいたオーラを取り除こうとしている.drift の問題は「#685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1)」 ([2011-03-13-1]) と「#686. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (2)」 ([2011-03-14-1]) でも取り上げたが,次のように提示することができる.話者個人は自らの人生の期間を超えて言語変化を継続させようとする動機づけなどもっていないはずなのに,なぜ世代を超えて伝承されているとしか思えない言語変化があるのか.あたかも言語そのものが話者を超越したところで生命をもっているかのような振る舞いを見せるのはなぜか.この問題を Ritt (215) のことばで示すと,次のようになる.

[S]ince individual speakers are normally not aware of the long-term histories of their languages and have no reason to be interested in them at all, it is difficult to see why they should be motivated to adjust their behaviour in communication or language acquisition to make the development of their language conform to any long-term trend.

この謎に対し,Ritt (215) は言語と話者についての3つの前提を理解することで解決できると述べる.

First, . . . the case can be made that even though whole language systems do not represent historical objects, their constituents do, because they are transmitted faithfully enough among speakers and thereby establish populations and lineages of constituent types which persist in time. Secondly, when speakers make choices among different variants of a linguistic constituent, they are not completely free. Instead their choice is always limited (a) by universal constraints on human physiology and (b) by socio-historical contingencies such as the relative prestige of different constituent variants. Since it would be against the self-interests of individual speakers to resist them, their choices can be expected to reflect physiological and social constraints more or less automatically. Thirdly, a speaker never chooses among isolated pairs of constituent variants. Instead constituent choice always occurs in the context of actual discourse, where any constituent of a linguistic system is always used and expressed in combination with others.

そして驚くべきことに,話者は上記の前提に基づく言語行動において,生理的,社会的な機械として機能しているにすぎないという見解が示される (215--16) .

In such interactions between constituents the role of speakers will be restricted to responding --- unconsciously and more or less automatically --- to physiological and social constraints on their communicative behaviour. In other words, speakers will not figure as autonomous, active and whimsical agents of change, but merely provide the mechanics through which linguistic constituents interact with each other.

このモデルによれば,話者は,個々の言語項目が相互に組み立てているネットワークのなかを動き回る,生理的よび社会的な機能を付与された媒質ということになる.話者が言語変化の主体ではなく媒介であるという提言は,きわめて controversial だろう.

・ Ritt, Nikolaus. "How to Weaken one's Consonants, Strengthen one's Vowels and Remain English at the Same Time." Analysing Older English. Ed. David Denison, Ricardo Bermúdez-Otero, Chris McCully, and Emma Moore. Cambridge: CUP, 2012. 213--31.

2013-02-07 Thu

■ #1382. 「言語変化はただ変化である」 [language_change][teleology][drift][unidirectionality]

言語変化をどのようにとらえるかという問題については,言語変化観の各記事で扱ってきた.著名な言語(英語)学者 David Crystal (2) の言語変化観をのぞいてみよう.

[L]anguage is changing around you in thousands of tiny different ways. Some sounds are slowly shifting; some words are changing their senses; some grammatical constructions are being used with greater or less frequency; new styles and varieties are constantly being formed and shaped. And everything is happening at different speeds and moving in different directions. The language is in a constant state of multidimensional flux. There is no predictable direction for the changes that are taking place. They are just that: changes. Not changes for the better; nor changes for the worse; just changes, sometimes going one way, sometimes another.

英語にせよ日本語にせよ,この瞬間にも,多くの言語項目が異なる速度で異なる方向へ変化している."multidimensional flux" とは言い得て妙である.また,言語変化に目的論的に定められた方向性 (teleology) はないという見解にも賛成する.一時的にはある方向をもっているに違いないが,恒久的に一定の方向を保ち続けることはないだろう(関連して unidirectionality の各記事を参照).ただし,一時的な方向とはいっても,drift として言及される印欧語族における屈折の衰退のように,数千年という長期にわたる「一時的な」方向もあるにはある.このように何らかの方向があるにせよ,それが良い方向であるとか悪い方向であるとか,価値観を含んだ方向ではないということは認めてよい.Crystal のいうように,"just changes" なのだろう.

「#432. 言語変化に対する三つの考え方」 ([2010-07-03-1]) および「#448. Vendryes 曰く「言語変化は進歩ではない」」 ([2010-07-19-1]) でも同じような議論をしたので,ご参照を.

・ Crystal, David. "Swimming with the Tide in a Sea of Language Change." IATEFL Issues 149 (1999): 2--4.

2011-10-10 Mon

■ #896. Kodak の由来 [etymology][root_creation][conversion][unidirectionality]

[2011-10-02-1]の記事「#888. 語根創成について一考」で触れた Kodak について.アメリカの写真機メーカー,コダック社の製品(主にカメラやフィルム)につけられた商標で,コダック社の創業者 George Eastman (1854--1932) の造語とされる.語根創成の典型例として挙げられることが多い.

商標としての初出は OED によると1888年で,一般名詞として「コダック(で撮影された)写真」の語義では1895年が初出.それ以前に,1891年には早くも品詞転換 (conversion) を経て,動詞としての「コダックで撮影する」も出現している.派生語 Kodaker, Kodakist, Kodakry も立て続けに現われ,当時のコダックの人気振りが偲ばれる.素人でも簡単に撮影できるのが売りで,そのことは当時の宣伝文句 "You press the button, we do the rest" からもよく表わされている.アメリカ英語では「シャッターチャンス」の意味で Kodak moment なる言い方も存在する.

Kodak という語の発明については詳しい経緯が書き残されている.ひ孫引きとなるが,Mencken に拠っている Strang (24) から引用する.

To the history of kodak may be added the following extract from a letter from its inventor, George Eastman (1854--1932) to John M. Manly Dec. 15, 1906: 'It was a purely arbitrary combination of letters, not derived in whole or in part from any existing word, arrived at after considerable search for a word that would answer all requirements for a trade-mark name. The principal of these were that it must be short, incapable of being mis-spelled so as to destroy its identity, must have a vigorous and distinctive personality, and must meet the requirements of the various foreign trade-mark laws, the English being the one most difficult to satisfy owing to the very narrow interpretation that was being given to their law at that time.' I take this from George Eastman, by Carl W. Ackerman; New York, 1930, p. 76n. Ackerman himself says: 'Eastman was determined that this product should have a name that could not be mis-spelled or mispronounced, or infringed or copied by anyone. He wanted a strong word that could be registered as a trade-mark, something that every one would remember and associate only with the product which he proposed to manufacture. K attracted him. It was the first letter of his mother's family name. It was "firm and unyielding." It was unlike any other letter and easily pronounced, Two k's appealed to him more than one, and by a process of association and elimination he originated kodak and gave a new name to a new commercial product. The trade-mark was registered in the United States Sept. 4, 1888.'

Eastman 自身の説明として,コダック社のHPにも次のような記述を見つけることができた.

I devised the name myself. The letter 'K' had been a favorite with me -- it seems a strong, incisive sort of letter. It became a question of trying out a great number of combinations of letters that made words starting and ending with 'K.' The word 'Kodak' is the result.

音素配列 (phonotactics) と音の与える印象を徹底的に考え抜いた上での稀な語根創成といえるだろう.

Strang (24--25) によると,初期の例からは「写真」や「フィルム」という普通名詞としての Kodak の使用が示唆されるが,商標から完全に普通名詞化したと考えられる hoover (掃除機)などとは異なり,普通名詞化の度合いは低いのではないかという.商標として始まった後,間もなく普通名詞化しかけたが,再び商標としてのみ使われることになった,という曲折を想定することができる.意味や用法の変化が必ずしも一方向ではないことを示唆する例と考えられるかもしれない.

・ Strang, Barbara M. H. A History of English. London: Methuen, 1970.

2011-03-13 Sun

■ #685. なぜ言語変化には drift があるのか (1) [drift][synthesis_to_analysis][grammaticalisation][unidirectionality][teleology]

言語変化の drift 「ドリフト,駆流,偏流,定向変化」について,本ブログの数カ所で取り上げてきた (see drift) .英語の drift はゲルマン語派の drift を継承しており,後者は印欧語族の drift を継承している.英語史と関連して指摘される最も顕著な drift は,analysis から synthesis への言語類型の変化だろう.これについては,Meillet を参照して[2011-02-12-1], [2011-02-13-1]などで取り上げた.

なぜ言語に drift というものがあるのか.これは長らく議論されてきているが,いまだに未解決の問題である.言語変化における drift はランダムな方向の流れではなく,一定の方向の流れを指す.しかも,短期間の流れではなく,何世代にもわたって持続する流れである.不思議なのは,言語変化の主体である話者は,言語を用いる際に過去からの言語変化の流れなど意識も理解もしていないはずにもかかわらず,一定方向の言語変化の流れを次の世代へ継いでゆくことである.言語変化の drift とは,話者の意識を超えたところで作用している言語に内在する力なのだろうか.もしそうだとすると,言語は話者から独立した有機体ということになる.論争が巻き起こるのは必至だ.

drift という用語は,アメリカの言語学者 Edward Sapir (1884--1939) が最初に使ったものである."Language moves down time in a current of its own making. It has a drift." (150) と言っており,あたかも言語それ自体が原動力となって流れを生み出しているかのような記述である.しかし,この言語有機体論に対して Sapir 自身が疑問を呈している箇所がある.

Are we not giving language a power to change of its own accord over and above the involuntary tendency of individuals to vary the norm? And if this drift of language is not merely the familiar set of individual variations seen in vertical perspective, that is historically, instead of horizontally, that is in daily experience, what is it? (154)

もちろん Sapir は,言語変化がそれ自身の力によってではなく,話者による言語的変異の無意識的な選択によって生じるということを認識してはいる.

The drift of a language is constituted by the unconscious selection on the part of its speakers of those individual variations that are cumulative in some special direction. (155)

しかし,話者がなぜ後に drift と分かるような具合に,世代をまたいである方向へ言語変化を推し進めてゆくのかは,相変わらず未知のままである.結局のところ,Sapir は drift とは mystical で impressive な現象であるという結論のようである.

Our very uncertainty as to the impending details of change makes the eventual consistency of their direction all the more impressive. (155)

付け加えれば,Sapir は英語が語彙を他言語から借用する傾向も drift であると考えている.

I do not think it likely, however, that the borrowings in English have been as mechanical and external a process as they are generally represented to have been. There was something about the English drift as early as the period following the Norman Conquest that welcomed the new words. They were a compensation for something that was weakening within. (170)

最後の "something" とは何なのか.

言語変化の方向の一定性という問題は,ここ30年の間に grammaticalisation の研究が進んだことによって新たな生命を吹き込まれた.grammaticalisation は言語変化の unidirectionality に焦点を当てているからである.Lightfoot は,これに激しく異を唱えている.もし言語に一定方向の drift が見られると仮定すると,一般に言語史にアクセスできないはずの話者にその原動力を帰すことはできない.とすると,何の力なのか.mystery 以外のなにものでもないではないか,と (International Encyclopedia of Linguistics, p. 399) .

Sapir 以来,drift の謎はいまだに解かれていない.

・ Sapir, Edward. Language. New York: Hartcourt, 1921.

・ Frawley, William J., ed. International Encyclopedia of Linguistics. 2nd ed. 2nd Vol. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2003.

2009-12-16 Wed

■ #233. 英語史の時代区分の歴史 (2) [periodisation][germanic][unidirectionality][speed_of_change]

昨日の記事[2009-12-15-1]で,Grimm が言語史の時代区分における "triadomany" の嚆矢だったことに言及した.彼によりドイツ語史が Old High German, Middle High German, New High German へ三区分される伝統が確立したが,ここには,単に三つの時代が時系列に沿って並列されたということ以上に,重要な言語変化に関する含みがあった.それは,言語変化は方向性 ( directionality ) をもっており,その変化の速度は時代が進むにつれて遅くなってきているという主張である.Grimm の弟子の一人である Förstemann は次のように述べている.

die Veränderung der deutschen Sprache zwischen dem 9. und 13. Jarhundert durchschnittlich eine etwa dreimal so große Schnelligkeit besessen hat als zwischen dem 13. und 19. Jahrhundert, daß also das Sprachleben in jener Zeit etwa dreimal so stark war als in dieser. (84)

平均すると 9 -- 13 世紀の言語変化は 13 -- 19 世紀の言語変化よりも3倍速く,後者は現代の言語変化よりも3倍速いということになる.ここにも「三倍」が現れており,"triadomany" の気味が濃厚である.そもそも言語変化のどの側面を比べて三倍なのか,言語変化の速度を数値化できるのか,いろいろと疑問が生じる.だが,ここで何よりも重要なのは,Grimm にせよ Förstemann にせよ,言語変化の方向性を前提としていることである.言語変化の速度を考慮している以上,ある方向に動いているということが前提にあるはずである.

だが,言語変化はある一定の方向に進む ( unidirectional ) ものなのだろうか? ここには,言語変化論の大きな問題が含まれている.

・Lass, Roger. "Language Periodization and the Concept of 'middle'." Placing Middle English in Context. Eds. Irma Taavitsainen, Terttu Nevalainen, Päivi Pahta and Matti Rissanen. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 7--41. esp. Page 13.

・Förstemann, Ernst. "Über die numerischen Lautverhältnisse im Deutschen." Germania: Neues Jahrbuch der Berlinischen Gesellschaft für deutsche Sprache und Alterthumskunde 7 (1846): 83--90.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow