2025-11-06 Thu

■ #6037. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形 [new_zealand_english][article][glottal_stop][consonant][vowel][phonetics][allomorph][phonetics][pronunciation]

冠詞 (article) (定冠詞と不定冠詞)の実現形は,英語の変種によっても,話者個人によっても,状況によっても様々である.典型的な機能語として強形と弱形の variants をもっているという事情もあり,状況はますます複雑となる(cf. 「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1])).さらに,後続語が子音で始まるか母音で始まるかによっても変異するので,厄介だ.

とりわけ定冠詞の実現形については,過去記事「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]),「#2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考」 ([2015-06-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

さて,地域変種によっても実現形はまちまちのようだが,New Zealand English の状況を見てみよう.Bauer (391) によると,後続音によらず定冠詞は /ðə/ ,不定冠詞は /ə/ と発音される傾向があるという.ただし,母音が後続する場合にはたいてい声門閉鎖音がつなぎとして挿入される.

As in South African English . . . , the and a do not always have the same range of allomorphs in New Zealand English that they have in standard English. Rather, they are realised as /ðə/ and /ə/ independent of the following sound. Where the following sound is a vowel, a [ʔ] is usually inserted.

目下ニュージーランド滞在中で NZE を耳にしているが,そもそも冠詞は弱く発音されることが多く,どの変種でも variants が多々あることを前提としてもっていたので,さほどマークしていなかった.今後は意識して聞き耳を立てていきたい.

別途 LPD で the を引いてみると,次のようにある.

the strong form ðiː, weak forms ði, ðə --- The English as a foreign language learner is advised to use ðə before a consonant sound (the boy, the house), ði before a vowel sound (the egg, the hour). Native speakers, however, sometimes ignore this distribution, in particular by using ðə before a vowel (which in turn is usually reinforced by a preceding [ʔ]), or by using ðiː in any environment, though especially before a hesitation pause. Furthermore, some speakers use stressed ðə as a strong form, rather than the usual ðiː.

NZE に限らず,他の変種においても実現形は多様と考えてよいだろう.また,つなぎの声門閉鎖音の挿入も,ある程度一般的といってよさそうだ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-11-06 Thu

■ #6037. New Zealand English における冠詞の実現形 [new_zealand_english][article][glottal_stop][consonant][vowel][phonetics][allomorph][phonetics][pronunciation]

冠詞 (article) (定冠詞と不定冠詞)の実現形は,英語の変種によっても,話者個人によっても,状況によっても様々である.典型的な機能語として強形と弱形の variants をもっているという事情もあり,状況はますます複雑となる(cf. 「#3713. 機能語の強音と弱音」 ([2019-06-27-1])).さらに,後続語が子音で始まるか母音で始まるかによっても変異するので,厄介だ.

とりわけ定冠詞の実現形については,過去記事「#906. the の異なる発音」 ([2011-10-20-1]),「#907. 母音の前の the の規範的発音」 ([2011-10-21-1]),「#2236. 母音の前の the の発音について再考」 ([2015-06-11-1]) などを参照されたい.

さて,地域変種によっても実現形はまちまちのようだが,New Zealand English の状況を見てみよう.Bauer (391) によると,後続音によらず定冠詞は /ðə/ ,不定冠詞は /ə/ と発音される傾向があるという.ただし,母音が後続する場合にはたいてい声門閉鎖音がつなぎとして挿入される.

As in South African English . . . , the and a do not always have the same range of allomorphs in New Zealand English that they have in standard English. Rather, they are realised as /ðə/ and /ə/ independent of the following sound. Where the following sound is a vowel, a [ʔ] is usually inserted.

目下ニュージーランド滞在中で NZE を耳にしているが,そもそも冠詞は弱く発音されることが多く,どの変種でも variants が多々あることを前提としてもっていたので,さほどマークしていなかった.今後は意識して聞き耳を立てていきたい.

別途 LPD で the を引いてみると,次のようにある.

the strong form ðiː, weak forms ði, ðə --- The English as a foreign language learner is advised to use ðə before a consonant sound (the boy, the house), ði before a vowel sound (the egg, the hour). Native speakers, however, sometimes ignore this distribution, in particular by using ðə before a vowel (which in turn is usually reinforced by a preceding [ʔ]), or by using ðiː in any environment, though especially before a hesitation pause. Furthermore, some speakers use stressed ðə as a strong form, rather than the usual ðiː.

NZE に限らず,他の変種においても実現形は多様と考えてよいだろう.また,つなぎの声門閉鎖音の挿入も,ある程度一般的といってよさそうだ.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

2025-09-30 Tue

■ #6000. 音声学セミナーにて「現代英語の発音と「大母音推移」」をお話ししました [notice][mindmap][gvs][phonetics][sound_change][spelling_pronunciation_gap][hel][academic_conference][vowel][diphthong]

「#5965. 現代英語の発音と「大母音推移」 --- 9月28日(日)の午後,日本音声学会の音声学セミナーにてお話しします」 ([2025-08-26-1]) でお知らせしたとおり,一昨日9月28日(日)に青山学院大学にて,日本音声学会音声学普及委員会主催の第35回音声学セミナーにて大母音推移 (gvs) についてお話しさせていただきました.セミナー本編に続き,質疑応答のセッションも合わせて3時間近くの長丁場でしたが,対面あるいはオンラインにて多くの方々にご参加いただき,私にとってもたいへん充実した会となりました.参加者の皆さん,ありがとうございました.また,学会長の斎藤弘子先生,音声学普及委員会の林良子先生,とりわけ夏休み前より企画準備でお世話になった内田洋子先生と牧野武彦先生には感謝申し上げます.

セミナーの概要については markmap によりマインドマップ化して整理しました(画像をクリックして拡大).

質疑応答セッションでは多くの質問をいただきましたが,時間の制限により,すべてにお答えすることができませんでした.今後,本ブログや Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」 などを通じて取り上げていきたいと思います.ぜひ今後も「大母音推移」にご注目ください.

2025-08-26 Tue

■ #5965. 現代英語の発音と「大母音推移」 --- 9月28日(日)の午後,日本音声学会の音声学セミナーにてお話しします [notice][gvs][phonetics][sound_change][spelling_pronunciation_gap][hel][academic_conference][vowel][diphthong]

日本音声学会音声学普及委員会の先生方よりお声がけいただき,1ヶ月ほど後の9月28日(日)14:00--17:00 に,第35回音声学セミナーにて標題でお話しさせていただくことになりました.英語史において最もよく知られる音変化の1つ,大母音推移 (Great Vowel Shift; gvs) を切り口として,現代英語の発音をめぐる多様性や変化について議論する予定です.

なぜ英単語 name は「ナメ」ではなく /neɪm/ と発音されるのか,room はなぜ「ローム」ではなく /ruːm/ なのか.英語を学習するなかで誰もが一度は抱く素朴な疑問でしょう.英語の綴字と発音の関係は一筋縄ではいかず,その不規則性は学習者(および教育者)を悩ませる大きな要因となっています.この「綴字と発音の乖離」 (spelling_pronunciation_gap) の背景には,様々な歴史的要因が横たわっていますが,そのなかでも広範な影響を及ぼしたのが,中英語期後期から近代英語期初期にかけて生じたとされる「大母音推移」です.この音変化関連する話題は本ブログでも「#205. 大母音推移」 ([2009-11-18-1]) を始め,多くの記事で取り上げてきました.

大母音推移は,一言でいえば,当時の英語のすべての長母音の音価が,連動して玉突きのように変化した現象です.上述の name を例にとれば,かつて /naːmə/ と発音されていた,その母音 /aː/ が上昇して /ɛː/,さらに /e;ː/ となり,最終的に2重母音化して /eɪ/ となりました.

この音変化は広範かつ体系的に生じましたが,すべての単語に,あるいはすべての地域で一律に適用されたわけではありませんでした.その浸透の不均一性,およびその後に生じた別の音変化の累積的な効果により,現代英語にみられる発音の多様性が生み出されるに至りました.現在の標準英語と非標準英語の違いや,世界諸英語間の差異に,大きな影響を及ぼしているのです.

今回のセミナーでは,この歴史的音変化の概要を解説するとともに,それが現代の多様な英語発音にどのようなインパクトを与えているのかにも光を当てたいと考えています.

本テーマは,音声学や英語史を専門とする方々はもちろんのこと,日々英語に接し,英語を教え,また学んでいる多くの方々にとっても興味深いテーマとなるはずです.とりわけ小中高の学校で英語を教えておられる先生方,将来英語教員を目指す学生の皆さんにとって,「なぜ英語の綴りと発音はこれほどまでに食い違っているのか」という生徒からの根源的な問いに,歴史的な視点から1つの答えを与えるヒントが得られる機会になると思います.

本セミナーは,青山学院大学での対面とオンライン (Zoom) でのハイブリッド開催となります.ご関心のある方は,ぜひご参加いただければ幸いです.以下に,学会サイトよりセミナーのご案内を要約します.

【 第35回音声学セミナー:現代英語の発音と「大母音推移」 】

・ 共催: 日本音声学会 音声学普及委員会,青山学院大学教育人間科学部附置教育人間科学研究所

・ 日時: 2025年9月28日(日)14:00--17:00

・ テーマ: 現代英語の発音と「大母音推移」

・ 講師: 堀田隆一(慶應義塾大学文学部教授)

・ 概要: なぜ name が /neɪm/ と,room が /ruːm/ と発音されるのか? 英語の綴りと発音の間に感じる「謎」は,歴史的な音変化に起因します.特に「大母音推移」は,現代英語の発音に大きな影響を与えました.本講演では,この歴史的変化を概説し,なぜ現代英語がこのような発音になったのかを解き明かします.さらに,音変化の不均一性が現代英語の発音の多様性にどう繋がるのかに目を向け,標準英語以外の多様な発音にも注目します.

・ 会場: (1)対面と(2)オンライン (Zoom) の同時ハイブリッド開催

・ (1)対面:青山学院大学 青山キャンパス・大学17号館17410教室

・ 〒150-8366 東京都渋谷区渋谷4-4-25

・ アクセスマップ

・ キャンパスマップ

・ (2)オンライン:Zoomリンクは,申込登録されたメールアドレス宛に開催前日までにお知らせします.

・ 定員: 対面100名,オンライン400名

・ 申込方法: 【事前登録制】 会員・非会員問わず,下記フォーム (Peatix) からお申し込み下さい.

・ フォーム

・ フォームの「チケットを申し込む」をクリックして下さい.

・ 登録には Peatix アカウントが必要です.アカウント作成にはメールアドレスや Google アカウントなどが使えます.

・ 登録期限: 9月26日(金)

・ 参加費:

・ 会員および学生は無料

・ 非会員一般1,500円

多くの皆さんのご参加をお待ちしております.

2025-07-05 Sat

■ #5913. これまでの音変化理論は弱い公式化にとどまる [history_of_linguistics][sound_change][phonetics][phonology][causation][language_change]

言語変化のなかでも音変化を説明することはとりわけ難しい.言語学の歴史において,「音変化理論」なるものはあるにはあるのだが,あくまで弱い仮説にとどまる.なぜ言語音は変化するのか? ある音変化が起こったとして,なぜそれはそのときに起こったのか? 音変化はある条件のもとに起こるのか,それとも無条件に起こるのか? 疑問を挙げだしたらキリがない.これらのいずれも満足に解決していないといってよい.

『音韻史』を著わした中尾は,その冒頭に近い「1.2 音変化理論」の最初に,次のように述べている.

19世紀以降の史的言語学の発達とともに「なぜ音は変化するか,それを引き起こす要因は何か」という問題が史的言語学にとって重要な関心の1つとなった.今世紀前半の記述言語学,後半からの変形生成理論等の言語理論の目ざましい発展とともに色々な変化理論が提案されてきた.変化理論は究極的には一定の時間内に起こる言語変化のおそらく複数の直接的原因を究明し,さらにそれを予知することにあるが,今日までの研究は主として言語変化への制約の公式化という弱い形をとっている.すなわち,音変化の要因を,言語的,社会的,心理的,生理的要因に求め,文脈依存の変化について文脈の研究が,文脈自由の変化については外的および内的要因の研究が行なわれてきた.

『音韻史』が書かれたのは1985年だが,それから40年経った今でも,上述の状況は本質的に変わっていない.英語史の音変化の各論においても,もちろん様々な考え方や理論は提案されてきたものの,「主として言語変化への制約の公式化という弱い形をとっている」状況に変わりがない.

私見では,言語変化のなかでも,とりわけ音変化は最後まで謎のままに残るタイプなのではないか.だからこそ引きつけられるものがある.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2025-05-30 Fri

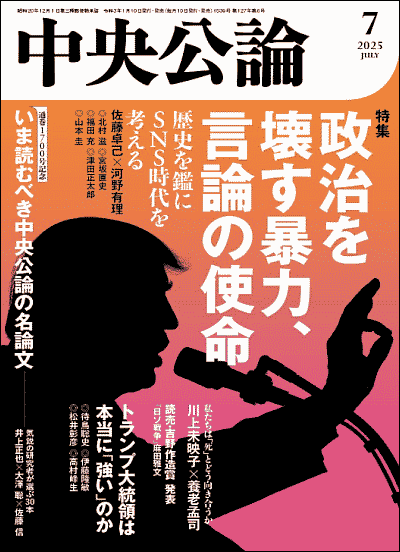

■ #5877. 発音とアクセントはどう移ろうか --- 水野太貴さんによる『中央公論』の連載より [yurugengogakuradio][notice][language_change][dialect][dialectology][stress][pronunciation][sound_change][japanese][phonetics][heldio]

今年度,興奮をもって追いかけている連載があります.言語学系 YouTube/Podcast チャンネル「ゆる言語学ラジオ」の水野太貴さんが,『中央公論』にて「ことばの変化をつかまえる」と題して執筆されているシリーズです.言語変化 (language_change) という,ともすれば専門的で敬遠されがちなテーマに光を当て,第一線の研究者へのインタビューを通じてその核心に迫ろうという,野心的な企画です.今年度は毎月本誌の発売を心待ちにするという習慣がついてしまいました.

連載第3回となる最新6月号では「発音とアクセントはどう移ろうか --- 歴史言語学者・平子達也さんに聞く」と題して,言語変化のなかでも特に根源的といえる音変化 (sound_change) が扱われています.私自身,英語史研究のなかで音韻や形態の変化を主たるフィールドとしてきただけに,今回のテーマにはとりわけ深い関心を抱きました.そして期待に違わず,今回の記事は心に深く刺さるものがありました.

音変化は言語変化における最大のミステリーである,と私は考えています.語彙や文法の変化も謎に満ちていておもしろいのですが,言語活動の基盤となる「音」が,なぜ,どのようにして変わるのかという問いは,最も捉えがたく,そして魅力的な謎なのです.専門家ですら説明に窮することの多いこの難題に,水野さんは南山大学の平子達也先生へのインタビューを通じてグイグイ迫っていきます.専門性の高いトピックをこれほど分かりやすく導入している文章を,私はあまり読んだことがありません.

記事は「なぜ発音は変わるのか」という素朴な疑問から始まります.平子先生は,その主要な動機の1つを「調音器官のスムーズな運動」への欲求,すなわち発音を楽にしたいという話者の都合に求めます.これは言語学で「最小努力の原則」 (The Principle of Least Effort) といわれているものです.私たちは無意識のうちに,発音を楽な方へと変化させている,というわけです.

しかし,もしこの原則だけが支配的ならば,すべての発音はどんどん簡略化され,例えば母音はすべて曖昧母音に収斂してしまうでしょう.すると,コミュニケーションの道具として機能不全に陥ってしまうはずです.しかし,現実はそうなっていなません.そこに「歯止め」となる力が働いているからです.

この点について,平子先生は次のように指摘されています (p. 171) .「言語というのは音だけで成るわけではありません.単語や文法など,ほかの体系と密接にかかわっていますから,それらとの兼ね合いで,一方向には進まないという事情があります.」

確かに音は語彙や文法といった言語体系の他の構成要素と固く結びついています.そして,平子先生は音変化の本質を次のように喝破します (p. 172) .「つまり発音の変化は,調音上の都合でラクしたいという動機と,その他の構成要素の制約のあいだで緊張関係を保ちながら起こるわけです.」

「緊張関係」という一言に,音変化のダイナミズムが凝縮されていますね.一方に引っ張る力と,それに抗うもう一方の力.その拮抗のなかで,言語は常に揺れ動き,姿を変えていきます.この記事は,その複雑なプロセスの存在を専門家でない読者にも実感させてくれます.ぜひ皆さんにこの記事を直接読んでいただければと思います.

今回ご紹介した記事は heldio でも「#1459. 音変化のミステリー --- ゆる言語学ラジオの水野太貴さんの『中央公論』連載「ことばの変化をつかまえる」より」として紹介しています.お聴きいただければ.

・ 水野 太貴 「連載 ことばの変化をつかまえる:発音とアクセントはどう移ろうか --- 歴史言語学者・平子達也さんに聞く」『中央公論』(中央公論新社)2025年6月号.2025年.168--75頁.

2025-05-18 Sun

■ #5865. 撥音「ん」の理論的解説 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal]

先日の記事「#5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史」 ([2025-05-16-1]) で,「撥音」の歴史的な記述を確認した.今回は同じ『日本語学研究事典』より,日本語に関する理論・一般言語学の観点からの「撥音」の記述 (p. 103--04) を読んでみたい.

【解説】仮名文字の「ン」に該当する音であり,はねる音ともいう.撥音に該当する音声と出現環境については,精密標記と簡略標記の設定水準により諸説あるが,概略,[ɴ]が語末,母音・半母音及び摩擦音 [s][ʃ]の直前,[ŋ]が軟口蓋音[ŋ][ɡ][k]の直前,[ɳ]が硬口蓋音[ɳ]の直前,[n]が歯茎音[n][d][dz][dʒ][t][ts][tʃ][ɾ]の直前,[m]が両唇音[m][b][p]の直前に位置し,相補分布をなしているといえる.そしてこれらの音声は,意味的対立に関与せず,鼻音という点で共通しており,直後の子音による環境同化を受けない[ɴ]以外,全てが直後の子音の環境同化により調音点を異にしていると解釈できることから,同一の音素に該当する異音であるとみることができる.これらの音声は,直後に母音を伴い共にモーラを構成する場合,互いに対立する別音素(例えば,[ŋ[n][m]は各/ŋ//n//m/)に該当する.その音声が子音の直前という環境で対立を失うことから,撥音音素は,中和音素であるということができる.中和音素は,慣例として,代表的異音にあたる音声記号のアルファベット上の大文字形を大文字〔ママ〕の大きさで記すことになっていることから,撥音の場合は,環境同化の影響を受けない[ɴ]を代表として,/N/で標記するのが一般的である.なお,モーラと音節の視点みると〔ママ〕,撥音は,促音と同様に,単独で独立したモーラを形成しながらも,単独では音節を構成できない音節副音であることから,単独で音声を構成できる自立モーラ(自立拍)に対して,特殊モーラ(特殊拍)と呼ばれ,該当する撥音音素/N/は,特殊音素と呼ばれる.

撥音を「中和音素」として解釈する視点は一見すると難しいのだが,これは日本語母語話者として認識している「ん」のあり方を,音韻論的に言いなおしたものだと考えると,何とも不思議な気がする.無意識に理解していることを明示的に説明しようとすると,こんなにも理論武装が必要なのか,と思うからである.言語学がオモシロ難しいのは,この辺りにポイントがあるのだろう.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-16 Fri

■ #5863. 撥音「ん」の歴史 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語の「ん」で表記される撥音は,日本語史でも後発の音である.『日本語学研究事典』の「撥音」の項目 (p. 355) より,音韻論および音声学の観点から「ん」の特殊性を覗いてみよう.

【解説】「はねる音」ともいう.中古に新たに発生した日本語音韻の一つ.促音とともに子音要素のみでモーラを校正するという,本来の日本語音韻にはなかった性質を付け加えた.モーラ表記には /N/ を用いる.ドキ(ドキ:[doki]:/doki/)に対するドンキ(ドンキ:[doŋki]:/doNki/)のように,モーラ /N/ があるかないかにより,語の意味の識別(弁別的特徴)がなされるところで成り立つ.音声面では,「漢文 [kambuN]」「漢字 [kan(d)zi]」「漢語 [kaŋŋo]」のように後続の子音の性質により異なる音となるが,それらは相補分布をなし同一音と解されて,モーラ /N/ が成り立つ.「撥ねる」とは,撥音から受ける感じによるとも,ンの字形(片仮名ニの変形ととる)に基づくとも言われる.撥音には,撥音便と漢字音の三内撥音尾のうちの [m][n]([ŋ] は母音ウに置き換えられた)とがある.漢文訓読資料を見ると,撥音の表記は様々であり,特に漢字音の撥音尾において顕著である.m 韻尾には,無表記「探タ」,ム表記「含カム」,ウ表記「林檎利宇古宇」などが,n 韻尾には,無表記「難ナ」,ニ表記「丹タニ」,イ表記「頬ホイ」,ウ表記「冠カウ」,特殊表記「鮮セレ」などが用いられている.『土佐日記』にも,「天気」を「てけ」,また「ていけ」と記している例がある.一般的には,m 韻尾はム,n 韻尾は無表記となることが多い.撥音 m と n との混同は一一世紀に入ると現れ,撥音のン表記も一一世紀後半には見られるようになる.

さらに,次の研究上の課題が触れられている.

【課題】漢文訓読資料に見るように,撥音の表記は特に漢字音において複雑微妙な姿を呈し,表記の背後にある,その実質に迫ることを困難なものとしている.撥音が日本語音として定着していく課程についても,十分に明らかになったとは言いがたく,一層の考究が必要である.

「ん」を侮ることなかれ.かなり奥深い問題である.

・ 『日本語学研究事典』 飛田 良文ほか 編,明治書院,2007年.

2025-05-15 Thu

■ #5862. 撥音「ん」や促音「っ」は母音的? [japanese][phonetics][phonology][phoneme][consonant][vowel][hiragana][romaji][syllable][mora][nasal]

先日の記事「#5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形」 ([2025-05-13-1]) に続き,日本語の撥音「ん」にまつわる話題.合わせて促音「っ」についても考える.

『日本語百科大事典』に「日本語音節の特性」と題する節がある (pp. 251--52) .そこで,撥音と促音に関する興味深い考察がある.いずれもローマ字表記では子音字表記されるので子音的と解されることの多い音だが,むしろ母音的なのではないかという洞察だ.252頁より引用する.

なお撥音や促音は一見,子音だけの音節として不自然のようにも思われるが,しかしそれらは,ある意味で母音の1種と見ることもできる.少なくとも語末の撥音・促音は,持続音(閉鎖や狭窄の持続)である点,m・n・ŋ や p・t・k の如き瞬間音(破裂あるいはそれに準ずるもの)と異なり,むしろ母音(開放の持続)に似ている.「三(サン)度・一(イッ)旦」など語中音の撥音・促音は,持続に破裂が伴うようだが,その破裂は撥音や促音の属性でなく,後続子音(ドの d やタの t)の属性と言える.

これに対し,英語の "bat" などの t は,閉鎖と破裂の両者を含むゆえ,日本人には「バット」の如く聞こえる.そういう意味で撥音や促音は,子音の n・t などと区別し,それぞれ N・T(あるいは Q)の如く表記するのが妥当である〔…〕.

これは音声学の問題でもあり,音韻論の問題でもある.英語を含めた多くの言語の事情と比べると,日本語の「特殊音素」は確かに特殊ではある.

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2025-05-13 Tue

■ #5860. 「ん」の発音の実現形 [japanese][phoneme][phonology][phonetics][consonant][nasal][romaji][hiragana]

日本語で「ん」と表記される音の実現形が多様であることは,よく知られている.音環境次第で,音声学的には必ずしも似ていない様々な音が,「ん」の実現のために用いられているのだ.方言や話者による個人差もあるものの,一般には次のように言われている.『日本語百科大事典』の「撥音」の項目 (pp. 246--47) より.

撥音「ん」は現れる位置によって音価が異なり,鼻子音になる場合と鼻母音になる場合とがある(以下に示す表記はかなり簡略なものである).

i) 鼻音・閉鎖音・流音の前

[m] 「3枚」 [sammai]

「3杯」 [sambai]

[n] 「女」 [onna]

「温度」 [ondo]

「本来」 [honrai]

[ŋ] 「金魚」 [kiŋŋjo]

ii) サ行子音・母音・半母音の前

[i᷈] 「単位」 [tai᷈i]([᷈] は [i] より少し広く鼻音化した音)

「電車」 [de᷈ʃa]

[ɯ᷈] 「困惑」 [koɯ᷈wakɯ]

「論争」 [roɯ᷈soː]

iii) 言い切り

たとえば「パン」と単独で発音した場合には [paɴ] と表記される.[ɴ] は口蓋垂の鼻音であるが,これは積極的な鼻子音であるというよりは,口蓋帆が下がり,口が若干閉じられることによって生じる音である(なお撥音を音韻表記では /ɴ/ と表わすが,この /ɴ/ と音声表記の /ɴ/ とは意味が異なる).

「ん」問題は音韻論の観点からも日本語史の観点からもおもしろい.また,「ん」はローマ字で表記するとどうなるのかという話題にかこつけて,英語綴字のトピックに関連づけてみるのもおもしろい.関連して,以下の記事群を参照.

・ 「#3852. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (1)」 ([2019-11-13-1])

・ 「#3853. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (2)」 ([2019-11-14-1])

・ 「#3854. なぜ「新橋」(しんばし)のローマ字表記 Shimbashi には n ではなく m が用いられるのですか? (3)」 ([2019-11-15-1])

・ 「#3855. なぜ「新小岩」(しんこいわ)のローマ字表記は *Shingkoiwa とならず Shinkoiwa となるのですか?」 ([2019-11-16-1])

・ 『日本語百科大事典』 金田一 春彦ほか 編,大修館,1988年.

2024-12-25 Wed

■ #5721. 音象徴は語の適者生存を助長する [evolution][sound_symbolism][phonaesthesia][phonetics][vowel]

昨日の記事「#5720. little の i は音象徴か?」 ([2024-12-24-1]) に引き続き,Jespersen による「[i] = 小さい」の音象徴 (sound_symbolism) に関する論考より.

Jespersen は同論文で当該の音象徴を体現する多くの例を挙げているが,冒頭に近い部分で,音象徴の議論にありがちな誤解2点について,注意深く解説している.

In giving lists of words in which the [i] sound has the indicated symbolic value, I must at once ask the reader to beware of two possible misconceptions: first, I do not mean to say that the vowel [i] always implies smallness, or that smallness is everywhere indicated by means of that vowel; no language is consistent in that way, and it suffices to mention the words big and small, or the fact that thick and thin have the same vowel, to show how absurd such an idea would be.

Next, I am not speaking of the origin or etymology of the words enumerated: I do not say that they have from the very first taken their origin from a desire to express small things symbolically. It is true that I believe that some of the words mentioned have arisen in that way,---many of our i-words are astonishingly recent---but for many others it is well-known that the vowel i is only a recent development, the words having had some other vowel in former times. What I maintain, then, is simply that there is some association between sound and sense in these cases, however it may have taken its origin, and however late this connexion may be (exactly as I think that we must recognize secondary echoisms). But I am firmly convinced that the fact that a word meaning little or little thing contains the sound [i], has in many, or in most, cases been strongly influential in gaining popular favour for it; the sound has been an inducement to choose and to prefer that particular word, and to drop out of use other words for the same notion, which were not so favoured. In other words, sound-symbolism makes some words more fit to survive and gives them a considerable strength in their struggle for existence. If you want to use some name of an animal for a small child, you will preferably take one with sound symbolism, like kid or chick . . . , rather than bat or pug or slug, though these may in themselves be smaller than the animal chosen. (285--86)

1つめは「[i] = 小さい」の音象徴は絶対的・必然的なものではなく,あくまで蓋然的なものにすぎない点の確認である.2つめは,当該の音象徴を体現している語について,その音形と意味の関係が語源の当初からあったのか,後に形成されたのかは問わないということだ.合わせて,共時的にも通時的にも,音象徴の示す関係は緩い傾向にとどまり,何かを決定する強い力をもっているわけではない点が重要である.

それでも Jespersen は,引用の最後でその用語を使わずに力説している通り,音象徴には語の「適者生存」 (survival of the fittest) を助長する効果があると確信している.音象徴は,言語において微弱ながらも常に作用している力とみなすことができるだろうと.

・ Jespersen, O. "Symbolic Value of the Vowel I." Philologica 1 (1922). Reprinted in Linguistica: Selected Papers in English, French and German. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard, 1933. 283--303.

2024-12-24 Tue

■ #5720. little の i は音象徴か? [sound_symbolism][phonaesthesia][phonetics][hellog_entry_set][link][sound_change][vowel]

音象徴 (sound_symbolism) は,言語学では伝統的に周辺的な扱いを受けてきた.この件については「#1269. 言語学における音象徴の位置づけ」 ([2012-10-17-1]) をはじめとする一連の記事で取り上げてきた.

そのような中で,Jespersen は異色である.1922年の論文で,英語やその他の言語における [i] の音象徴について熱っぽく論じているのだ.論文の冒頭から熱い.

Sound symbolism plays a greater role in the development of languages than is admitted by most linguists. In this paper I shall attempt to show that the vowel [i], high-front-unround, especially in its narrow or thin form, serves very often to indicate what is small, slight, insignificant, or weak. (283)

[i] が「小さい」と結びつけられる音象徴は広く知られており,本ブログでも「#242. phonaesthesia と 遠近大小」 ([2009-12-25-1]) で触れた.Jespersen は,この論文のなかで,多くの例を挙げながら [i] の「小ささ」についてグイグイと議論していく.

特におもしろいのは, little という,この話題との関連で真っ先に思い浮かぶ英単語についての論考である."Semantic and Phonetic Changes" と題する第7節で,次のように述べている.

The influence on sound development is first seen in the very word little. OE. lytel shows with its y, that the vowel must originally have been u, and this is found in OSax. luttil, OHG. luzzil; cf. Serb. lud 'little' and OIr. lútu 'little finger' (Falk and Torp); but then the vowel in Goth. leitils (i.e. lītils and ON. lítinn is so difficult to account for on ordinary principles that the NED. in despair thinks that the two words are "radically unconnected". I think we have here an effect of sound symbolism. The transition in E. from y to it of course is regular, being found in innumerable words in which sound symbolism cannot have played any role, but in modern English we have a further slight modification of the sound which tends to make the word more expressive, I refer to the form represented in spelling as "leetle". In Gill's Logonomia (1621, Jiriczek's reprint 48), where he mentions the "particle" tjni (j is his sign for the diphthong in sign) he writes "a lïtle tjni man" with ï (his sign for the vowel in seen), though elsewhere he writes litle with short i. NED. under leetle calls it "a jocular imitation of a hesitating (?) or deliberately emphatic pronunciation of little". Payne mentions from Alabama leetle "with special and prolonged emphasis on the î sound to indicate a very small amount". I suspect that what takes place is just as often a narrowing or thinning of the vowel sound as a real lengthening, just as in Dan. bitte with narrow or thin [i], see above. To the quotations in NED. I add the following: Dickens Mutual Fr. 861 "a leetle spoilt", Wells Tono-B. 1. 92 "some leetle thing", id. War and Fut. 186 "the little aeroplane ... such a leetle thing up there in the night".---It is noteworthy that in the word for the opposite notion, where we should according to the usual sound laws expect the vowel [i] (OE. micel, Sc. mickle, Goth. mikils) we have instead u: much, but this development is not without parallels, see Mod. E. Gr. I. 3. 42. In Dan. dial, mög(el) for the same word the abnormal vowel is generally ascribed to the influence of the labial m; in both forms the movement away from i may have been furthered by sound-symbolic feeling. (301--02)

「[i] = 小さい」という音象徴について,little の母音はポジティヴに,対義語 much の母音はネガティヴに反応し音変化を経てきた,という鋭い洞察だ.もともとの語源形との関連で音象徴を論じるのみならず,音変化の動機づけとしての音象徴を考察していくこともまた重要なのではないかと気付かされた.

・ Jespersen, O. "Symbolic Value of the Vowel I." Philologica 1 (1922). Reprinted in Linguistica: Selected Papers in English, French and German. Copenhagen: Levin & Munksgaard, 1933. 283--303.

2024-11-04 Mon

■ #5670. Grassmann's law --- 「グラスマンの法則」 [grassmanns_law][grimms_law][sound_change][sanskrit][greek][indo-european][dissimilation][verners_law][aspiration][phonetics][consonant]

著名なグリムの法則 (grimms_law) には,提案された当時より,様々な例外があることが気づかれていた.最も有名なのはヴェルネルの法則 (verners_law) に関する例外だが,もう1つグラスマンの法則 (grassmanns_law) というものがある.『新英語学辞典』 '(209--300) より,該当の解説を引く.

次に発見された例外は,通常グラスマンの法則 (Grassmann's law) と呼ばれるものである.ある系列の印欧語の対応は Grimm が設定した型に合致せず,説明が困難であったが,Herman Grassmann (1809--77) はギリシア語やサンスクリットのデータを調べ,これらの言語では例外的に不規則な対応を発達させたことを明らかにした.例えば

Goth. Skt -biudan 'offer' bódhāmi 'notice' dauhtar 'daughter' duhitā' gagg 'street' jánghā 'leg'

等の対応において,グリムの法則によればゲルマン語の b, d, g に対応するサンスクリットの語頭は帯気音 (bh, dh, gh) でなければならないのに非帯気音である.Grassmann は,これはギリシア語およびサンスクリットにおいて,二つの隣接する音節で帯気音が続いたとき,どちらか一つは異化 (DISSIMILATION) によって非帯気音になる現象のせいであることを発見した.ここにおいて言語学者は,単音の特徴や音声環境だけでなく,相接する音節との関係にも注意しなければならないことを知ったのである.

Bussmann の用語辞典からも引いておこう (198--99) .

Grassmann's law (also dissimilation of aspirates)

Discovered by Grassmann (1863), sound change occurring independently in Sanskrit and Greek which consistently results in a dissimilation of aspirated stops. If at least two aspirated stops occur in a single word, then only the last stop retains its aspiration, all preceding aspirates are deaspirated; cf. IE *bhebhoṷdhe > Skt bubodha 'had awakened,' IE *dhidhēhmi > Grk títhēmi 'I set, I put.' This law, which was discovered through internal reconstruction, turned a putative 'exception' to the Germanic sound shift (⇒ 'Grimm's law). . . into a law.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics''. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-10-28 Mon

■ #5663. 音節とは何か? [syllable][mora][terminology][phonology][prosody][phonetics][sobokunagimon]

標題は素朴な疑問だが,実は言語学的には簡単には答えられない.音節 (syllable) は音声学でも基本的な概念だが,実は一般的な定義を与えるのが難しいのだ.Bussmann の言語学用語集を読んでみよう.

syllable

Basic phonetic-phonological unit of the word or of speech that can be identified intuitively, but for which there is no uniform linguistic definition. Articulatory criteria include increased pressure in the airstream . . . , a change in the quality of individual sounds . . . , a change in the degree to which the mouth is opened. Regarding syllable structure, a distinction is drawn between the nucleus (= 'crest,' 'peak,' ie. the point of greatest volume of sound which, as a rule, is formed by vowels) and the marginal phonemes of the surrounding sounds that are known as the head (= 'onset,' i.e. the beginning of the syllable) and the coda (end of the syllable). Syllable boundaries are, in part, phonologically characterized by boundary markers. If a syllable ends in a vowel, it is an open syllable; if it ends in a consonant, a closed syllable. Sounds, or sequences of sounds that cannot be interpreted phonologically as syllabic (like [p] in supper, which is phonologically one phone, but belongs to two syllables), are known as 'interludes.'

ある個別言語の音節は母語話者にとって直感的に理解される単位だが,言語一般を念頭において客観的に定式化しようと試みても,うまくいかない.調音音声学や聴覚音声学の側からの定義,または音韻理論的な解釈などがあるものの,必ずしもきれいには定義できない.それでいて母語話者は音節という単位を「知っている」らしいというのだから,不思議だ.

音節をめぐっては,hellog でも関連する話題を取り上げてきた.以下の記事などを参照.

・ 「#347. 英単語の平均音節数はどのくらいか?」 ([2010-04-09-1])

・ 「#1440. 音節頻度ランキング」 ([2013-04-06-1])

・ 「#1513. 聞こえ度」 ([2013-06-18-1])

・ 「#1563. 音節構造」 ([2013-08-07-1])

・ 「#3715. 音節構造に Rhyme という単位を認める根拠」 ([2019-06-29-1])

・ 「#4621. モーラ --- 日本語からの一般音韻論への貢献」 ([2021-12-21-1])

・ 「#4853. 音節とモーラ」 ([2022-08-10-1])

・ Bussmann, Hadumod. Routledge Dictionary of Language and Linguistics. Trans. and ed. Gregory Trauth and Kerstin Kazzizi. London: Routledge, 1996.

2024-09-21 Sat

■ #5626. 古英語の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化 (2) [sound_change][phonetics][consonant][palatalisation][oe][digraph][spelling][alliteration][aelfric]

以前に「#1511. 古英語期の sc の口蓋化・歯擦化」 ([2013-06-16-1]) で取り上げた話題.古英語の2重字 (digraph) である <sc> について,依拠する文献を Prins に変え,そこで何が述べられているかを確認し,理解を深めたい.Prins (203--04) より引用する.

7.16 PG sk

PG sk was palatalized:

1. In initial position before all vowels and consonants:

OE Du sčēap 'sheep' schaap WS sčield A scčeld 'shield' schild sčēawian 'to show' schouwen G schauen sčendan 'to damage' schenden sčrud 'shroud'

2. Medially between palatal vowels and especially when followed originally by i(:) or j:

þrysče 'thrush'

wysčean 'to wish'

3. Finally after palatal vowels:

æsč 'ash'

disč 'dish'

Englisč 'English'

古英語研究では通常,口蓋化した <sc> の音価は [ʃ] とされているが,Prins (204) の注によると,本当に [ʃ] だったかどうかはわからないという.むしろ [sx] だったのではないかと議論されている.

Note 2. In reading OE we generally read sc(e) as [ʃ], but there is no definite proof that this was the pronunciation before the ME period (when the French spelling s, ss is found, and the spelling sh is introduced).

In Ælfric sc alliterates with sp, and st. So s must have been the first element. The second element cannot have been k, since Scandinavian loanwords (which must have been adopted in lOE) still have sk: skin, skill.

The pronunciation in OE was probably [sx]. Cf. Dutch schoon [sxo:n], schip [sxip], which in the transition period to eME or in eME itself, must have become [ʃ].

・ Prins, A. A. A History of English Phonemes. 2nd ed. Leiden: Leiden UP, 1974.

2024-09-18 Wed

■ #5623. 「英語史ライヴ2024」で B&C の第57節 "Chronological Criteria" を対談精読実況生中継しました [bchel][latin][borrowing][methodology][sound_change][palatalisation][loan_word][oe][chronology][lexicology][phonetics][hellive2024]

一昨日の Voicy heldio にて「#1205. Baugh and Cable 第57節を対談精読実況生中継 --- 「英語史ライヴ2024」より」をアーカイヴ配信しました.これは「#5607. 「英語史ライヴ2024」で B&C の第57節 "Chronological Criteria" を対談精読実況生中継します」 ([2024-09-02-1]) で予告したとおり,9月8日(日)に開催された「英語史ライヴ2024」の早朝枠にて生配信された番組がもとになっています.

金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)がメインMCを務め,小河舜さん(上智大学)と私が加わる形での対談精読実況生中継でした.ヘルメイト(helwa リスナー)や khelf メンバーも数名がギャラリーとして収録現場に居合わせ,生配信でお聴きになったリスナーものべ81名に達しました.たいへんな盛況ぶりです.皆さん,日曜日の朝から盛り上げてくださり,ありがとうございました.

今回取り上げたセクションは,実はテクニカルです.古英語期のラテン借用語について,それぞれの単語が同時期内でもいつ借りられたのか,いわば借用の年代測定に関する方法論が話題となっています.取り上げられているラテン借用語の例はすこぶる具体的ではありますが,音変化の性質や比較言語学の手法に光を当てる専門的な内容となっています.

しかし,今回の対談精読会にそってに丁寧に英文を読み解いていえば,必ず理解できますし,歴史言語学研究のエキサイティングな側面を体験することもできるでしょう.本編48分ほどの長尺ですが,ぜひお時間のあるときにゆっくりお聴きください.

Baugh and Cable の精読シリーズのバックナンバー一覧は「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) に掲載しています.ぜひこの機会にテキストを入手して,第1節からお聴きいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-09-15 Sun

■ #5620. study の第1音節母音が短母音であることについて [senbonknock][sobokunagimon][phonetics][phonology][french][latin][loan_word][syllable][monophthong][hellive2024][heldio]

「#5618. 早朝の素朴な疑問「千本ノック」 with 小河舜さん --- 「英語史ライヴ2024」より」 ([2024-09-13-1]) で紹介した,Voicy heldio の「早朝の素朴な疑問「千本ノック」 with 小河舜さん」にて,本編の40分30秒くらいから「study と student で <u> の部分の発音の仕方が異なるのはなぜですか?」という問いが取り上げられています.「#3295. study の <u> が短母音のわけ」 ([2018-05-05-1]) の説明では不十分ではないか,という指摘がありました.

上記「千本ノック」では手元に詳しい情報がない状態での即興の回答だったのですが,その後,詳しく調べてみると,いろいろと込み入った事情があるようです.study の第1音節母音が短母音であるのは,この単語がもともとはラテン語由来でありながら,フランス語を経由してきたという経緯が関与していそうです.

これについては,英語音韻史を書いた中尾 (339) に手がかりがあった.

F [= French] 借入語の音量:OF [= Old French] の母音は CL [= Classical Latin] の音量ではなく,VL [= Vulgar Latin] の閉音節では短く,開音節では長いという原則を受け継いだ.ME [= Middle English] の音組織は F 借入語を通してこの新しい型の音量をしばしば反映する.

ここで短母音になる具体的な音環境が3点ほど挙げられているのだが,その1つに「3音節動詞,名詞,形容詞の第1音節」がある(中尾,p. 340).動詞 study の中英語形 studien が,この項目の多数の例の1つとして挙げられている(赤字で示した).

(3) 3音節動詞,名詞,形容詞の第1音節:banisshen (=banish)/ravisshen (=ravish)/vanisshen (=vanish)/perishen (=perish)/finishen (=finish)/florisshen (=flourish)/norishen (=nourish)/publisshen (=publish)/punisshen (=punish)/travailen (=travail)/honouren (=honour)/visiten (=visit)/governen (=govern)/studien (=study)/family/salary/memory/remedy/misery/chalaundre (=calendar)/chapitre (=chapter)/sepulcre/oracle/miracle/ministre (=minister)/vinegre (=vinegar)/covenant/rethorik (=rhetoric)/bacheler (=bachelor)/charitee (=charity)/vanite (=vanity)/jolitee (=jollity)/povertee (=poverty)/libertee (=liberty)/trinitee (=trinity)/facultee (=faculty)/vavasour/amorous/casuel (=casual)/natural/general/lecherous/seculer (=secular)/diligent

動詞 study は,中英語では stud・ī・en のように3音節語でした.この場合,現代の2音節語 stu・dent とは異なり,第1音節が閉音節となるために問題の母音が短く保たれる,といった理屈となります.

・ 中尾 俊夫 『音韻史』 英語学大系第11巻,大修館書店,1985年.

2024-09-02 Mon

■ #5607. 「英語史ライヴ2024」で B&C の第57節 "Chronological Criteria" を対談精読実況生中継します [bchel][latin][borrowing][methodology][sound_change][palatalisation][loan_word][oe][chronology][lexicology][phonetics][hellive2024]

Baugh and Cable による英語史の古典的名著を Voicy heldio にて1節ずつ精読していくシリーズをゆっくりと進めています.昨年7月に開始した有料シリーズですが,たまの対談精読回などでは通常の heldio にて無料公開しています.

9月8日(日)に12時間 heldio 生配信の企画「英語史ライヴ2024」が開催されますが,当日の早朝 8:00-- 8:55 の55分枠で「Baugh and Cable 第57節を対談精読実況生中継」を無料公開する予定です.金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)と小河舜さん(上智大学)をお招きし,日曜日の朝から3人で賑やかな精読回を繰り広げていきます.

テキストをお持ちでない方のために,当日精読することになっている第57節 "Chronological Criteria" (pp. 73--75) の英文を以下に掲載しておきます.古英語期のラテン借用語の年代測定に関するエキサイティングな箇所です.じっくりと予習しておいていただけますと,対談精読実況生中継を楽しく聴くことができると思います.

57. Chronological Criteria. In order to form an accurate idea of the share that each of these three periods had in extending the resources of the English vocabulary, it is first necessary to determine as closely as possible the date at which each of the borrowed words entered the language. This is naturally somewhat difficult to do, and in the case of some words it is impossible. But in a large number of cases it is possible to assign a word to a given period with a high degree of probability and often with certainty. It will be instructive to pause for a moment to inquire how this is done.

The evidence that can be employed is of various kinds and naturally of varying value. Most obvious is the appearance of the word in literature. If a given word occurs with fair frequency in texts such as Beowulf, or the poems of Cynewulf, such occurrence indicates that the word has had time to pass into current use and that it came into English not later than the early part of the period of Christian influence. But it does not tell us how much earlier it was known in the language, because the earliest written records in English do not go back beyond the year 700. Moreover, the late appearance of a word in literature is no proof of late adoption. The word may not be the kind of word that would naturally occur very often in literary texts, and so much of Old English literature has been lost that it would be very unsafe to argue about the existence of a word on the basis of existing remains. Some words that are not found recorded before the tenth century (e.g., pīpe 'pipe', cīese 'cheese') can be assigned confidently on other grounds to the period of continental borrowing.

The character of the word sometimes gives some clue to its date. Some words are obviously learned and point to a time when the church had become well established in the island. On the other hand, the early occurrence of a word in several of the Germanic dialects points to the general circulation of the word in the Germanic territory and its probable adoption by the ancestors of the English on the continent. Testimony of this kind must of course be used with discrimination. A number of words found in Old English and in Old High German, for example, can hardly have been borrowed by either language before the Anglo-Saxons migrated to England but are due to later independent adoption under conditions more or less parallel, brought about by the introduction of Christianity into the two areas. But it can hardly be doubted that a word like copper, which is rare in Old English, was nevertheless borrowed on the continent when we find it in no fewer than six Germanic languages.

The most conclusive evidence of the date at which a word was borrowed, however, is to be found in the phonetic form of the word. The changes that take place in the sounds of a language can often be dated with some definiteness, and the presence or absence of these changes in a borrowed word constitutes an important test of age. A full account of these changes would carry us far beyond the scope of this book, but one or two examples may serve to illustrate the principle. Thus there occurred in Old English, as in most of the Germanic languages, a change known as i-umlaut. (Umlaut is a German word meaning 'alteration of sound', which in English is sometimes called mutation.) This change affected certain accented vowels and diphthongs (æ, ā, ō, ū, ēa, ēo , and īo) when they were followed in the next syllable by an ī or j. Under such circumstances, æ and a became e, and ō became ē, ā became ǣ, and ū became ȳ. The diphthongs ēa, ēo, īo became īe, later ī, ȳ. Thus *baŋkiz > benc (bench), *mūsiz > mȳs, plural of mūs (mouse), and so forth. The change occurred in English in the course of the seventh century, and when we find it taking place ina word borrowed from Latin, it indicates that the Latin word had been taken into English by that time. Thus Latin monēta (which became *munit in Prehistoric OE) > mynet (a coin, Mod. E. mint) and is an early borrowing. Another change (even earlier) that helps us to date a borrowed word is that known as palatal diphthongization. By this sound change ǣ or ē in early Old English was changed to a diphthong (ēa and īe, respectively) when preceded by certain palatal consonants (ċ, ġ, sc). OE cīese (L. cāseus, chesse) mentioned earlier, shows both i-umlaut and palatal diphthongization (cāseus > *ċǣsi > *ċēasi > *ċīese). In many words, evidence for date is furnished by the sound changes of Vulgar Latin. Thus, for example, an intervocalic p (and p in the combination pr) in the Late Latin of northern Gaul (seventh century) was modified to a sound approximating a v, and the fact that L. cuprum, coprum (copper) appears in OE as copor with the p unchanged indicates a period of borrowing prior to this change (cf. F. cuivre). Again Latin ī changed to e before A.D. 400 so that words like OE biscop (L. episcopus), disc (L. discus), sigel 'brooch' (L. sigillum), and the like, which do not show this change, were borrowed by the English on the continent. But enough has been said to indicate the method and to show that the distribution of the Latin words in Old English among the various periods at which borrowing took place rests not upon guesses, however shrewd, but upon definite facts and upon fairly reliable phonetic inferences.

Baugh and Cable の精読シリーズのバックナンバー一覧は「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) に掲載しています.ぜひこの機会にテキストを入手して,第1節からお聴きいただければ.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-07-07 Sun

■ #5550. Fertig による Sturtevant's Paradox への批判 [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change][phonotactics][prosody]

昨日の記事「#5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」 ([2024-07-06-1]) の最後で,Fertig が "Sturtevant's Paradox" に批判的な立場であることを示唆した.Fertig (97--98) の議論が見事なので,まるまる引用したい.

Like a lot of memorable sayings, Sturtevant's Paradox is really more of a clever play on words than a paradox, kind of like 'Isn't it funny how you drive on a parkway and park on a driveway.' There is nothing paradoxical about the fact that phonetically regular change gives rise to morphological irregularities. Similarly, it is no surprise that morphologically motivated change tends to result in increased morphological regularity. 'Analogic creation' would be even more effective in this regard if it were regular, i.e. if it always applied across the board in all candidate forms, but even the most sporadic morphologically motivated change is bound to eliminate a few morphological idiosyncrasies from the system.

If we consider analogical change from the perspective of its effects on phonotactic patterns, it is sometimes disruptive in just the way that one would expect . . . . At one point in the history of Latin, for example, it was completely predictable that s would not occur between vowels. Analogical change destroyed this phonological regularity, as it has countless others. Carstairs-McCarthy (2010: 52--5) points out that analogical change in English has been known to restore 'bad' prosodic structures, such as syllable codas consisting of a long vowel followed by two voiced obstruents. Although Carstairs-McCarthy's examples are all flawed, there are real instances, such as believed < beleft, of the kind of development he is talking about (§5.3.1).

What the continuing popularity of Sturtevant's formulation really reveals is that one old Neogrammarian bias is still very much with us: When Sturtevant talks about changes resulting in 'regularity' and 'irregularities', present-day historical linguists still share his tacit assumption that these terms can only refer to morphology. If we were to revise the 'paradox' to accurately reflect the interaction between sound change and analogy, we would wind up with something not very paradoxical at all:

Sound change, being phonetically/phonologically motivated, tends to maintain phonological regularity and produce morphological irregularity. Analogic creation, being morphologically motivated, tends to produce phonological irregularity and morphological regularity. Incidentally, the former tends to proceed 'regularly' (i.e. across the board with no lexical exceptions) while the latter is more likely to proceed 'irregularly' (word-by-word).

I realize that this version is not likely to go viral.

一言でいえば,言語学者は,言語体系の規則性を論じるに当たって,音韻論の規則性よりも形態論の規則性を重視してきたのではないか,要するに形態論偏重の前提があったのではないか,という指摘だ.これまで "Sturtevant's Paradox" の金言を無批判に受け入れてきた私にとって,これは目が覚めるような指摘だった.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Carstairs-McCarthy, Andrew. The Evolution of Morphology. Oxford: OUP, 2010.

2024-07-06 Sat

■ #5549. Sturtevant's Paradox --- 音変化は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推は不規則だが規則性を生み出す [sound_change][analogy][neogrammarian][phonetics][phonology][morphology][language_change]

標題は,さまざまに言い換えることができる.「音法則は規則的だが不規則性を生み出し,類推による創造は不規則だが規則性を生み出す」ともいえるし,「形態論において規則的な音声変化はエントロピーを増大させ,不規則的な類推作用はエントロピーを減少させる」ともいえる.音変化 (sound_change) と類推 (analogy) の各々の特徴をうまく言い表したものである(昨日の記事「#5548. 音変化と類推の峻別を改めて考える」 ([2024-07-05-1]) を参照).この謂いについては,以下の関連する記事を書いてきた.

・ 「#1693. 規則的な音韻変化と不規則的な形態変化」 ([2013-12-15-1])

・ 「#838. 言語体系とエントロピー」 ([2011-08-13-1])

・ 「#1674. 音韻変化と屈折語尾の水平化についての理論的考察」 ([2013-11-26-1])

この金言を最初に述べたのは誰だったかを思い出そうとしていたが,Fertig を読んでいて,それは Sturtevant であると教えられた.Fertig (96) より,関連する部分を引用する.

Long before there was a Philosoraptor, historical linguists had 'Sturtevant's Paradox': 'Phonetic laws are regular but produce irregularities. Analogic creation is irregular but produces regularity' (Sturtevant 1947: 109). It is catchy and memorable. It has undoubtedly helped generations of linguistics students remember the battle between sound change and analogy, and, on the tiny scale of our subdiscipline, it is no exaggeration to say that it has 'gone viral', making appearances in numerous textbooks . . . and other works . . . .

確かにキャッチーな金言である.しかし,Fertig はこのキャッチーさゆえに見えなくなっている部分があるのではないかと警鐘を鳴らしている.

・ Fertig, David. Analogy and Morphological Change. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2013.

・ Sturtevant, Edgar H. An Introduction to Linguistic Science. New Haven: Yale UP, 1947.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow