2013-04-29 Mon

■ #1463. euphuism [style][literature][inkhorn_term][johnson][emode][renaissance][alliteration][rhetoric]

「#292. aureate diction」 ([2010-02-13-1]) で,15世紀に発生したラテン借用語を駆使する華麗語法について見た.続く16世紀には,inkhorn_term と呼ばれるほどのラテン語かぶれした語彙が押し寄せた.これに伴い,エリザベス朝の文体はラテン作家を範とした技巧的なものとなった.この技巧は John Lyly (1554--1606) によって最高潮に達した.Lyly は,Euphues: the Anatomy of Wit (1578) および Euphues and His England (1580) において,後に標題にちなんで呼ばれることになった euphuism (誇飾体)という華麗な文体を用い,初期の Shakespeare など当時の文芸に大きな影響を与えた.

euphuism の特徴としては,頭韻 (alliteration),対照法 (antithesis),奇抜な比喩 (conceit),掛けことば (paronomasia),故事来歴への言及などが挙げられる.これらの修辞法をふんだんに用いた文章は,不自然でこそあれ,人々に芸術としての散文の魅力をおおいに知らしめた.例えば,Lyly の次の文を見てみよう.

If thou perceive thyself to be enticed with their wanton glances or allured with their wicket guiles, either enchanted with their beauty or enamoured with their bravery, enter with thyself into this meditation.

ここでは,enticed -- enchanted -- enamoured -- enter という語頭韻が用いられているが,その間に wanton glances と wicket guiles の2重頭韻が含まれており,さらに enchanted . . . beauty と enamoured . . . bravery の組み合わせ頭韻もある.

euphuism は17世紀まで見られたが,17世紀には Sir Thomas Browne (1605--82), John Donne (1572--1631), Jeremy Taylor (1613--67), John Milton (1608--74) などの堂々たる散文が現われ,世紀半ばからの革命期以降には John Dryden (1631--1700) に代表される気取りのない平明な文体が優勢となった.平明路線は18世紀へも受け継がれ,Joseph Addison (1672--1719), Sir Richard Steele (1672--1729), Chesterfield (1694--1773),また Daniel Defoe (1660--1731), Jonathan Swift (1667--1745) が続いた.だが,この平明路線は,世紀半ば,Samuel Johnson (1709--84) の荘重で威厳のある独特な文体により中断した.

初期近代英語期の散文文体は,このように華美と平明とが繰り返されたが,その原動力がルネサンスの熱狂とそれへの反発であることは間違いない.ほぼ同時期に,大陸諸国でも euphuism に相当する誇飾体が流行したことを付け加えておこう.フランスでは préciosité,スペインでは Gongorism,イタリアでは Marinism などと呼ばれた(ホームズ,p. 118).

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ 石橋 幸太郎 編 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

・ U. T. ホームズ,A. H. シュッツ 著,松原 秀一 訳 『フランス語の歴史』 大修館,1974年.

2013-03-30 Sat

■ #1433. 10世紀以前の古英語テキストの分布 [oe_dialect][manuscript][dialect][map][dialectology][literature]

中英語の方言区分については「#130. 中英語の方言区分」 ([2009-09-04-1]) ほか,me_dialect の各記事で扱ってきたが,古英語の方言状況については本ブログではあまり触れていなかった.古英語の方言地図については,「#715. Britannica Online で参照できる言語地図」 ([2011-04-12-1]) でリンクを張った Encyclopedia - Britannica Online Encyclopedia の The distribution of Old English dialects が簡便なので,参照の便のためにサイズを小さくした版を以下に再掲する.

古英語の方言は,慣習的に,Northumbrian, Mercian (この2つを合わせて Anglian とも呼ぶ), West-Saxon, Kentish の4つに区分される.ただし,4方言に区分されるといっても,古英語の方言が実際に4つしかなかったと言えるわけではない.どういうことかといえば,文献学者が現代にまでに伝わる写本などに表わされている言語を分析したところ,言語的諸特徴により4方言程度に区分するのが適切だろうということになっている,ということである.現在に伝わる古英語テキストは約3000テキストを数えるほどで,その総語数は300万語ほどである.この程度の規模では,相当に幸運でなければ,詳細な方言特徴を掘り出すことはできない.また,地域的な差違のみならず,古英語期をカバーする数世紀の時間的な差違も関与しているはずであり,実際にあったであろう古英語の多種多様な変種を,現存する証拠により十分に復元するということは非常に難しいことなのである.

11世紀の古英語後期になると,West-Saxon 方言による書き言葉が標準的となり,主要な文献のほとんどがこの変種で書かれることになった.しかし,10世紀以前には,他の方言により書かれたテキストも少なくない.実際,時代によってテキストに表わされる方言には偏りが見られる.これは,その方言を担う地域が政治的,文化的に優勢だったという歴史的事実を示しており,そのテキストの地理的,通時的分布がそのまま社会言語学的意味を帯びていることをも表わしている.

では,10世紀以前の古英語テキストに表わされている言語の分布を,Crystal (35--36) が与えている通りに,時代と方言による表の形で以下に示してみよう.それぞれテキストの種類や規模については明示していないので,あくまで分布の参考までに.

| probable date | Northumbrian | Mercian | West Saxon | Kentish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 675 | Franks Casket inscription | |||

| 700 | Ruthwell Cross inscription | Epinal glosses Charters | ||

| 725 | Person and place-names in Bede, Cædmon's Hymn, Bede's Death Song | Person and place-names in Bede, Charters | ||

| 750 | Leiden Riddle | Charters | Charters | |

| 775 | Blickling glosses, Erfurt glosses, Charters | Charters | ||

| 800 | Corpus glosses | |||

| 825 | Vespasian Psalter glosses, Lorica Prayer, Lorica glosses | Charters | ||

| 850 | Charters | Charters, Medicinal recipes | ||

| 875 | Charters, Royal genealogies, Martyrologies | |||

| 900 | Cura pastoralis, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle | |||

| 925 | Orosius, Anglo-Saxon Chronicle | |||

| 950 | Royal glosses | Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, Medicinal recipes | Charters, Kentish Hymn, Kentish Psalm, Kentish proverb glosses | |

| 975 | Rushworth Gospel glosses, Lindisfarne Gospel glosses, Durham Ritual glosses | Rushworth Gospel glosses |

大雑把にまとめれば,7世紀は Northumbrian(Bede [673?--735] などの学者が輩出),8世紀は Mercian(Offa 王 [?--796] の治世),9世紀は West-Saxon(Alfred the Great [849--99] の治世)が栄えた時期といえるだろう.Kentish は,政治的権威とは別次元で,6世紀以降,イングランドにおけるキリスト教の本山として宗教的な権威を保ち続けたために,その存在感や影響力は諸テキストに反映されている.

古英語方言学の難しさは,4方言のそれぞれがテキストで純粋に現われるというよりは,選り分けるのに苦労するくらい異なる方言が混在した状態で現われることが少なくないからである.歴史方言学は,それぞれの時代に特有の状況があるがゆえに,特有の問題が生じるのが常である.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2012-11-10 Sat

■ #1293. Sir Orfeo の関連サイト [link][romance][sir_orfeo][literature][auchinleck]

大学院の授業で,"Breton lay" と呼ばれるジャンルに属する中英語ロマンス Sir Orfeo を,Burrow and Turville-Petre 版に基づいて読み始める.比較として,Bliss, Sisam, Treharne による版を使用.

・ Bliss, A. J., ed. Sir Orfeo. 2nd ed. Oxford: Clarendon, 1966.

・ Burrow, J. A. and Thorlac Turville-Petre, eds. A Book of Middle English. 3rd ed. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2005.

・ Sisam, Kenneth, ed. Fourteenth Century Verse and Prose. Oxford: OUP, 1921.

・ Treharne, Elaine, ed. Old and Middle English c. 890--c. 1450: An Anthology. 3rd ed. Malden, Mass.: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

Web上で関連するリソースを探したので,以下にまとめておく.

・ Page from the Online Database of the Middle English Verse Romances: 中英語ロマンスの総合サイトより粗筋と刊本の情報.

・ Page from Middle English Compendium HyperBibliography: MED よりテキスト情報.

・ Page from Wikipedia

・ Text and Manuscript from the Auchinleck Manuscript: Auchinleck 版のテキストと写本画像.研究書誌はこちら.

・ Text: Laskaya and Salisbury's edition (based on Auchinleck): イントロや研究書誌はこちら.Auchinleck MS については,「#744. Auchinleck MS の重要性」 ([2011-05-11-1]) も参照.

・ Text: Shuffleton's edition (based on Ashmole): イントロはこちら.

・ Introduction and Text: Hostetter's edition

・ Modern English translation in the Hannah Scot Manuscripts

・ Modern English translation by Hunt

2012-03-06 Tue

■ #1044. 中英語作品,Chaucer,Shakespeare,聖書の略記一覧 [chaucer][shakespeare][bible][bibliography][literature][abbreviation]

Chaucer など中英語の文学テキストをはじめとして,英語史で引用されることの多い主要な作品の略記を一覧にしておくと便利である.そこで,『英語語源辞典』 (xvii--xx) より,中英語作品,Chaucer,Shakespeare,聖書の書名の略記を抜き出した.関連して MED の HyperBibliography も参照.

ME期主要作品の成立年代と作品名(MED による略形)

| ?lateOE | Lambeth Homilies |

| a1121--60 | Peterb. Chron. = Peterborough Chronicle |

| c1175 | Body & Soul |

| ?c1175 | Poema Morale |

| ?a1200 | Ancrene Riwle |

| ?a1200 | Layamon Brut |

| ?c1200 | St. Juliana |

| ?c1200 | St. Katherine |

| ?c1200 | St. Margaret |

| ?c1200 | Hali Meidenhad |

| ?c1200 | Sawles Warde |

| ?c1200 | Ormulum |

| c1200 | Vices & Virtues |

| ?c1225 | Horn |

| c1250 | Owl & Nightingale |

| c1250 | Floris |

| c1250 | Genesis & Exodus |

| c1275 | Kentish Sermons |

| ?a1300 | Kyng Alisaunder |

| ?a1300 | Richard Coer de Lyon |

| c1300 | Havelok |

| c1300 | Gloucester Chronicle |

| c1300 | South English Legendary |

| c1303 | Mannyng Handlyng Synne |

| a1325 | Cursor Mundi |

| c1330 | Orfeo |

| a1333 | Shoreham Poems |

| a1338 | Mannyng Chronicle |

| 1340 | Ayenbite |

| c1340 | Rolle Psalter |

| c1350 | Prose Psalter |

| c1353 | Wynnere & Wastoure |

| a1375 | William of Palerne |

| 1375 | Barbour The Bruce |

| a1376 | Piers Plowman A |

| a1378 | Piers Plowman B |

| ?c1380 | Cleanness |

| ?c1380 | Patience |

| ?c1380 | Pearl |

| c1384 | Wycl. Bible (1) = Wycliffite Bible |

| c1386 | St. Erkenwald |

| ?a1387 | Piers Plowman C |

| a1387 | Trevisa Polychronicon |

| ?c1390 | Gawain = Sir Gawain and the Green Knight |

| a1393 | Gower Confessio Amantis |

| c1395 | Wycl. Bible (2) = Wycliffite Bible |

| ?c1395 | Pierce the Ploughman's Creed |

| a1396 | Hilton Scale of Perfection |

| a1398 | Trevisa Bartholomew |

| ?a1400 | Destruction of Troy |

| ?a1400 | Morte Arthure |

| c1400 | Mandeville |

| ?a1425 | Polychronicon (Harley) |

| ?a1425 | Chauliac (1) = Guy de Chauliac's Grande Chirurgie |

| ?c1425 | Chauliac (2) = Guy de Chauliac's Grande Chirurgie |

| ?a1438 | MKempe = Book of Margery Kempe |

| 1440 | Promp. Parv. = Promptorium Parvulorum |

| ?a1450 | Gesta Romanorum |

| a1470 | Malory |

Chaucer 作品名の略形(MED による略形)

| ABC | An ABC |

| Adam | Chaucers Wordes Unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn |

| Anel. | Anelida and Arcite |

| Astr. | A Treatise on the Astrolabe |

| Bal. Ch. | A Balade of Complaint |

| BD | The Book of the Duchess |

| Bo. | Boece |

| Buk. | Lenvoy de Chaucer a Bukton |

| Comp. A. | Complaynt D'Amours |

| Comp. L. | Complaint to His Lady |

| CT. | The Canterbury Tales |

| CT. Cl. | The Clerk's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Co. | The Cook's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. CY. | The Canon's Yeoman's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Fkl. | The Franklin's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Fri. | The Friar's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Kn. | The Knight's Tale |

| CT. Mch. | The Merchant's Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue |

| CT. Mk. | The Monk's Tale |

| CT. Mcp. | The Manciple's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Mel. | The Tale of Melibee |

| CT. Mil. | The Miller's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. ML. | The Man of Law's Introduction, Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue |

| CT. Mk. | The Monk's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. NP. | The Nun's Priest's Prologue, Tale, and Epilogue |

| CT. Pard. | The Pardoner's Introduction, Prologue, and Tale |

| CT. Pars. | The Parson's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Ph. | The Physician's Tale |

| CT. Pri. | The Prioress's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Prol. | General Prologue |

| CT. Rt. | Chaucer's Retraction |

| CT. Rv. | The Reeve's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Sh. | The Shipman's Tale |

| CT. SN. | The Second Nun's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Spurious Pard. Sh. Link | The Spurious Pardoner-Shipman Link |

| CT. Sq. | The Squire's Introduction and Tale |

| CT. Sum. | The Summoner's Prologue and Tale |

| CT. Th. | The Prologue and Tale of Sir Thopas |

| CT. WB. | The Wife of Bath's Prologue and Tale |

| Form. A. | The Former Age |

| Fort. | Fortune |

| Gent. | Gentilesse |

| HF | The House of Fame |

| LGW | The Legend of Good Women |

| LGW Prol. | Prologue |

| L. St. | Lak of Stedfastnesse |

| Mars | The Complaint of Mars |

| Merc. B. | Merciles Beaute |

| PF | The Parliament of Fowls |

| Pity | The Complaint unto Pity |

| Prov. | Proverbs |

| Purse | The Complaint of Chaucer to His Purse |

| Rosem. | To Rosemounde |

| RRose | The Romaunt of the Rose |

| Scog. | Lenvoy de Chaucer a Scogan |

| TC | Troilus and Criseyde |

| Truth | Truth |

| Ven. | The Complaint of Venus |

| W. Unc. | Against Women Unconstant |

Shakespeare 作品名の略形(The Riverside Shakespeare (1974) による略形)

| AWW | All's Well That Ends Well |

| AYL | As You Like It |

| Ado | Much Ado About Nothing |

| Ant | Antony and Cleopatra |

| Cor | Coriolanus |

| Cym | Cymbeline |

| Err | The Comedy of Errors |

| 1H4 | 1 Henry IV |

| 2H4 | 2 Henry IV |

| H5 | Henry V |

| 1H6 | 1 Henry VI |

| 2H6 | 2 Henry VI |

| 3H6 | 3 Henry VI |

| H8 | Henry VIII |

| Ham | Hamlet |

| JC | Julius Caesar |

| Jn | King John |

| LC | Lover's Complaint |

| LLL | Love's Labour's Lost |

| Lr | King Lear |

| Luc | The Rape of Lucrece |

| MM | Measure for Measure |

| MND | A Midsummer-Night's Dream |

| MV | The Merchant of Venice |

| MWW | The Merry Wives of Windsor |

| Mac | Macbeth |

| Oth | Othello |

| Per | Pericles |

| Phoe | The Phoenix and Turtle |

| R2 | Richard II |

| R3 | Richard III |

| RJ | Romeo and Juliet |

| Shr | The Taming of the Shrew |

| Son | Sonnets |

| TC | Troilus and Cressida |

| TGV | The Two Gentlemen of Verona |

| TNK | The Two Noble Kinsmen (with Fletcher) |

| TN | Twelfth Night |

| Tem | Tempest |

| Tim | Timon of Athens |

| Tit | Titus Andronicus |

| VA | Venus and Adonis |

| WT | The Winter's Tale |

英訳聖書 (AV) 書名の略形

| Acts | The Acts of the Apostles |

| Amos | Amos |

| 1 Chron. | The First Book of the Chronicles |

| 2 Chron. | The Second Book of the Chronicles |

| Col. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Colossians |

| 1 Cor. | The First Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians |

| 2 Cor. | The Second Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Corinthians |

| Dan. | The Book of Daniel |

| Deut. | The Fifth Book of Moses, called Deuteronomy |

| Eccles. | Ecclesiastes, or the Preacher |

| Ephes. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Ephesians |

| Esth. | The Book of Esther |

| Exod. | The Second Book of Moses, called Exodus |

| Ezek. | The Book of the Prophet Ezekiel |

| Ezra | Ezra |

| Gal. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Galatians |

| Gen. | The First Book of Moses, called Genesis |

| Hab. | Habakkuk |

| Hag. | Haggai |

| Heb. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Hebrews |

| Hos. | Hosea |

| Isa. | The Book of the Prophet Isaiah |

| James | The General Epistle of James |

| Jer. | The Book of the Prophet Jeremiah |

| Job | The Book of Job |

| Joel | Joel |

| John | The Gospel according to St. John |

| 1 John | The First Epistle General of John |

| 2 John | The Second Epistle of John |

| 3 John | The Third Epistle of John |

| Jonah | Jonah |

| Josh. | The Book of Joshua |

| Jude | The General Epistle of Jude |

| Judges | The Book of Judges |

| 1 Kings | The First Book of the Kings |

| 2 Kings | The Second Book of the Kings |

| Lam. | The Lamentations of Jeremiah |

| Lev. | The Third Book of Moses, called Leviticus |

| Luke | The Gospel according to St. Luke |

| Mal. | Malachi |

| Mark | The Gospel according to St. Mark |

| Matt. | The Gospel according to St. Matthew |

| Mic. | Micah |

| Nah. | Nahum |

| Neh. | The Book of Nehemiah |

| Num. | The Fourth Book of Moses, called Numbers |

| Obad. | Obadiah |

| 1 Pet. | The First Epistle General of Peter |

| 2 Pet. | The Second Epistle General of Peter |

| Philem. | The Epistle of Paul to Philemon |

| Philip. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Philippians |

| Prov. | The Proverbs |

| Ps. | The Book of Psalms |

| Rev. | The Revelation of St. John the Divine |

| Rom. | The Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Romans |

| Ruth | The Book of Ruth |

| 1 Sam. | The First Book of Samuel |

| 2 Sam. | The Second Book of Samuel |

| Song of Sol. | The Song of Solomon |

| 1 Thess. | The First Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Thessalonians |

| 2 Thess. | The Second Epistle of Paul the Apostle to the Thessalonians |

| 1 Tim. | The First Epistle of Paul the Apostle to Timothy |

| 2 Tim. | The Second Epistle of Paul the Apostle to Timothy |

| Titus | The Epistle of Paul to Titus |

| Zech. | Zechariah |

| Zeph. | Zephaniah |

| 紊???? (Apocrypha) | |

| Baruch | Baruch |

| Bel and Dragon | The History of the Destruction of Bel and the Dragon |

| Ecclus. | The Wisdom of Jesus the Son of Sirach, or Ecclesiasticus |

| 1 Esd. | I. Esdras |

| 2 Esd. | II. Esdras |

| Judith | Judith |

| 1 Macc. | The First Book of the Maccabees |

| 2 Macc. | The Second Book of the Maccabees |

| Pr. of Man | The Prayer of the Manasses |

| Rest of Esther | The Rest of the Chapters of the Book of Esther |

| Song of Three Children | The Song of the Three Holy Children |

| Susanna | The History of Susanna |

| Tobit | Tobit |

| Wisd. of Sol. | The Wisdom of Solomon |

・ 寺澤 芳雄 (編集主幹) 『英語語源辞典』 研究社,1997年.

2011-02-28 Mon

■ #672. 構造主義的にみる中英語ロマンス [literature][romance][formula]

[2011-02-26-1], [2011-02-27-1]の記事で参照した Wittig は,中英語ロマンスの formula を機能的な単位として位置づけた研究者である.Wittig の議論には構造主義の視点が色濃く反映されており,それは特に次の2点において見られる.

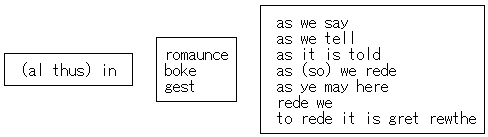

1つは,formula を "a kind of mental template, in the mind of the poet, a pattern-making device which generates a series of derivative forms" (Wittig 29) とみなしている点である.この考えによると,formula とは統合関係 ( syntagm ) を表わす「型」のことであり,そこに選択関係 ( paradigm ) にある交替可能な語句群から1つを選んで流し込んでゆくことによってある表現が実現されるとする.例えば al thus in boke as as we rede という決まり文句は,以下の「型」の各スロットに適当な語句を選択して当てはめていった結果であると考える.

もう1つすぐれて構造主義的なのは,上記のような統語レベルの型を "syntagmeme" と名付けてロマンスの構造をなす最小単位と位置づけたあとで,「交替可能な選択肢の中からの選択」という考え方をより大きな単位へと拡張してゆく点である.例えば,ロマンスには「主人公の父の死」という場面がある.この場面を構成するのは「悪者による殺害の企み」「父の登場」「敵の挑戦」「敵との戦い」「死」という一連の出来事であり,それぞれの出来事の単位は "motifeme" と呼ばれる.各 motifeme には様々な variation が用意されており,また motifeme 間の順番は決まっている.型に流し込むかのように場面が構成されてゆく.次に,「主人公の父の死」という場面それ自体がより大きな構成単位 "type-scene" となり,「主人公の追放」というもう1つの type-scene と合わさって,さらに大きな構成単位 "type-episode" となる.いずれの規模の単位においても「交替可能な選択肢の中からの選択」という同一原則が適用されており,小さい単位の積み重ねにより最終的な物語が構成されるという意味で,きわめて構造主義的な考え方といえる.

Wittig は,"Dame," he said のような単純な formula の分析から始め,より大きな単位へと分析へと積み上げてゆき,結論として中英語ロマンスに共通する2対の type-episode 連鎖を突き止めた."love-marriage" 連鎖と "separation-restoration" 連鎖である.Wittig (177) は,中英語ロマンスの形式上の定義はこの2対の連鎖が組み合わさっているということであると言い切る.

中英語ロマンスでは,love と marriage の間に必ず困難が伴い,separation (追放によるアイデンティティの喪失)と restoration (その回復)にも苦難が付随する.2対の連鎖こそが中英語ロマンスの主要な "generating forces" であり,深層構造から,鋳型へ内容物を注入しつつ,表層構造を産出してゆく原動力なのである.

最後に,Wittig の議論は壮大な speculation へと及ぶ.中英語ロマンスの聴衆の関心の根底に love-marriage と separation-restoration があったと仮定すると,それはなぜなのか.その答えの1つとして,love-marriage が象徴する女系家族制と separation-restoration が象徴する男系家族制との融和が,かれらの大きな関心事だったからではないか.

formula の言語的分析から中世イングランドの家族観へと展開する Wittig の議論を読んで,構造主義というのは,小さな部品を1つの原理で組み合わせて大きな機械を作りあげることなのかと学んだ.

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

2011-02-27 Sun

■ #671. 中英語ロマンスにおける formula の機能 [literature][romance][auchinleck][formula]

昨日の記事[2011-02-26-1]で,中英語ロマンスの言語において formula がいかに大きな割合で用いられているかを見た.ロマンスに formula が多用される背景には,いくつかの説明が提案されている.1つは,有名な The Auchinleck Manuscript のロマンス群に関連して特に言われていることで,ロンドンの写本製作所が「売れ筋本」を大量生産するために,formula を機械的に多用したという "a theory of bookshop composition and extensive textual borrowing" である (Wittig 13) .もう1つは,ロマンスは,吟遊詩人が口頭で聴衆へ伝えるという意図で作成されたものであり,語りの効果と暗唱のために繰り返しが多くなるのは自然だとする "the oral-transmission theory" である (Wittig 14) .

しかし,Wittig は上の2つの説明では説得力がないと主張する.ロマンスが中世イングランドの聴衆に受けたのは,分かりきった物語の筋や予測可能な formula を何度も聞かされることにより,物語が描く社会の現状を確認し,是認し,安心感を得ることができたからではないか.ロマンスの語り手と聞き手はともに社会の秩序に対する信頼感をもっており,ロマンスを受容することによって,その秩序を保守することに賛意を表明しているのではないか.したがって,社会が変革すればロマンスというジャンル自体も変容を迫られるか衰退することになる.ロマンスの言語は,語り手と聞き手のスタンスの言語 "a language of stance" (Wittig 46) である.Wittig のこの主張が要約された一節を引く.

If the language does not serve to carry information, what then is its primary function? In addition to carrying a minimal amount of narrative information, the language carries at least one other level of social meaning as well. That is, it carries the additional messages which are encoded within the semiology of social gestures, the language of social ritual: leave-takings, greetings, meals and banquets, marriages and knightings and tournaments. Each one of the highly ritualized events to which the formulas themselves refer is also a kind of formulaic language, a complex system of significations which is as thoroughly understood and articulated in its own culture as that culture's natural language and which is indeed a language even though it may not be a verbal one. In the romances the language of the verse refers much of the time to this second-order system, and its message-bearing function is then doubled. The language of these narratives functions not only as a medium of narrative, but as a powerful social force which supports, reinforces, and perpetuates the social beliefs and customs held by the culture, perhaps long past their normal time of decline. (Wittig 45)

上で触れた The Auckinleck Manuscript については以下のサイトが有用である.

・ The Auchinleck Manuscript : National Library of Scotland

・ Auchinleck MS Home Page

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

2011-02-26 Sat

■ #670. 中英語ロマンスにおける formula の割合 [literature][romance][statistics][formula]

中世ロマンスの言語上の大きな特徴の1つに,formula の多用がある.stock phrase とも言われ「決まり文句,常套句」を指す.formula の定義には,表現の幅を限定したきわめて狭いものから,語彙や統語のレベルでの型に適合していればよいとする広いものまであるが,多くの formula 研究は Milman Parry の次の定義から出発している.

A formula is "a group of words which is regularly employed under the same metrical conditions to express a given essential idea." (qtd in Wittig, p. 15 as from "Studies in the Epic Technique of Oral Verse-Making. I: Homer and Homeric Style." Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 41 (1930). page 80.)

formula の具体例を挙げればきりがないが,"'Dame,' he said", "that hendi knight", "feyre and free" などの短いものから,"He was a bolde man and a stowt", "And he were neuer so blythe of mode", "For to make the lady glade / That was bothe gentyll and small" などの長いものまで様々である.Wittig によれば,中英語の韻文ロマンス25作品から Parry の条件を厳密に満たす formula を含む行を抜き出したところ,以下のような結果が得られた.

| POEM | LENGTH | VERSE TYPE | FORMULA RATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lai le freine | 340 lines | couplet | 10% |

| Sir Landeval | 500 | couplet | 11 |

| Sir Launfal | 1044 | tail-rhyme | 16 |

| King Horn | 1644 | couplet | 18 |

| Sir Degare | 1076 | couplet | 21 |

| Havelok | 2822 | couplet | 21 |

| Sir Isumbras | 804 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Sir Amadace | 864 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Sir Perceval | 2288 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Horn Child | 1138 | tail-rhyme | 24 |

| Roswall and Lillian | 885 | couplet | 25 |

| Ocatvian (southern) | 1962 | tail-rhyme | 25 |

| Sir Triamour | 1719 | tail-rhyme | 25 |

| Earl of Toulous | 1224 | tail-rhyme | 26 |

| Ywain and Gawayn | 4032 | couplet | 27 |

| Sir Eglamour | 1377 | tail-rhyme | 29 |

| Squyr of Lowe Degre | 1131 | couplet | 30 |

| Lebeaus Desconus | 2131 | tail-rhyme | 30 |

| Sir Torrent | 2669 | tail-rhyme | 31 |

| Bevis of Hampton | 4332 | couplet | 34 |

| Eger and Grime | 1474 | couplet | 35 |

| Sir Degrevant | 1920 | tail-rhyme | 38 |

| Octavian (northern) | 1731 | tail-rhyme | 39 |

| Floris and Blancheflur | 1083 | couplet | 41 |

| Emare | 1030 | tail-rhyme | 42 |

平均をとると,各テキストを構成する行数の26.56%が formula を含んでいることになる.couplet では平均が24.82%,tail-rhyme では27.93%だが,大差はない.また,テキストの長さと formula 行の割合には強い相関はない.Wittig の研究では,Arthur,Troy,Alexander ものなどの "cycle" は含まれていない.参照テキストを限定し,定義を厳密にし,あくまで低めに抑えられた数え上げなので,定義を緩くすれば相当に数値が上がるはずだという.

ロマンスのテキストの約1/4が formula から成っているとすると,聴衆にとって次にどのような文言が現われるかは予測可能ということになる.また,ロマンスは物語としての筋もおよそ決まっているので,聴衆にとって「新情報」を得る機会は非常に少ないと考えられる.では,そのようなロマンスが中世に大流行したのはなぜか.聴衆はロマンスに何を期待していたのだろうか.

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

2011-02-15 Tue

■ #659. 中英語 Romaunce の意味変化とジャンルとしての発展 [literature][romance][semantic_change]

[2010-11-06-1]の記事で romance という語の語源と romance という文学ジャンルの発生との関係を見た.ジャンルとしての romance は12世紀後半のフランスに始まり,英文学では13世紀終わりになってようやく現われた.フランスでもイギリスでも romans あるいは romaunce は,ジャンルとして成長するにつれ,多義的になっていった.逆にいえば語義の発展の仕方を見ることで,ジャンルとしてどのように発展していったかも分かるということである.

まずフランスではどのように捉えられたか.[2010-11-06-1]の記事で見たとおり,romans は文字通りには「ロマンス語」を原義とした.具体的にはラテン語に対する土着語 ( vernacular language ) としての古フランス語 ( Old French ) を指す.フランスの書き手たちは,Statius の Thebaid, Virgil の Aeneid, Benoît de Sainte-Maure のトロイ陥落,Wace のブリテン史など,主にラテン語で伝えられた古代の物語 ( romans d'antiquité ) を,ラテン語を解さない人々にも理解できるように romans (土着のフランス語)で書き直した.ここから,romans は「フランス語で書かれた物語」を意味するようになった.この初期の romans の書き手たちは,後にジャンルとしてのロマンスと結びつけられる種々の特徴を特に意図していたわけではなかったが,情事,登場人物の心理,奇妙で不思議な出来事といった主題に光を当てる独創性を示していたのは確かである.romans の語義がある特徴をもった物語の主題を指すようになるのは12世紀の終わり,ロマンスのジャンルを明確に切り開いた Chrétien de Troyes 辺りからと考えられる.口承法と詩形の観点からも,歌われる chançon ではなく語られる物語として,武勲詩の節 laisse ではなく8音節詩行 ( octosyllabic ) として,romans は独自性を帯びてくるようになる.こうして,フランス語の romans は,「フランス語」,「フランス語で書かれた物語」,「内容的にある特徴をもった物語」,「形式的にある特徴をもった物語」へと意味を発展させ,文学ジャンルを表わす一般呼称として徐々に定着していった.

意味変化の用語で整理すると,「言語」から「その言語で書かれたもの」への換喩 ( metonymy ) と,「その言語で書かれたもの」から「内容的にある特徴をもった物語」への意味の特殊化 ( specialisation ) が生じていることになる.

次に,イギリスにおける romaunce の語義の発展はどうだったろうか.フランスの romans 作品は,Anglo-Norman という媒体を通じて早くからイギリスにもたらされていたが,英語という媒体に乗せられるのは13世紀も終わり頃のことである.ほぼすべてがフランス語からの翻訳であったので,英語 romaunce は当初は「フランス語で書かれた物語」を広く指す意味として出発した.しかし,時間をおかずに,媒体言語ではなく主題に注目する新たな語義も派生した.媒体言語が英語であっても,ある人物に焦点を当てた物語は広く romaunce と呼ばれるようになった.ある人物の人生が描かれる際に,しばしば幻想的な脚色や色事が付加されたが,説教文学はその点を取り上げて romaunce を世俗的なものとして非難した.興味深いことに,説教文学が自らを romaunce と対立させたその観点こそが romaunce という文学を後に特徴づけることになったのである.中世(そして現代)におけるロマンス文学の世俗的な人気を考えると,皮肉なことである.こうして,英語の romaunce は「フランス語で書かれた物語」,「ある人物に焦点を当てた物語」,「内容的にある特徴をもった物語」へと語義を発展させていった.ここでも,意味の特殊化 ( specialisation ) が生じている.

・ Strohm, Paul. "The Origin and Meaning of Middle English Romaunce." Genre 10.1 (1977): 1--28.

2010-11-06 Sat

■ #558. Romance [literature][romance][etymology]

日本語で「ロマンス」といって一般的に想起されるのは恋愛物語だろう.文学のジャンルとしてのロマンスは,中世以来様々な発展を遂げながら現代にまで強い影響力を及ぼしている.一方で,比較言語学の分野で「ロマンス」といえば,インドヨーロッパ語族のイタリック語派の主要な諸言語を含むロマンス語派のことを指す.具体的には,ラテン語とそこから派生したフランス語,スペイン語,ポルトガル語,イタリア語,プロバンス語,レト=ロマンシュ語,ルーマニア語,カタルニア語などの総称である.では,「ロマンス」のこの2つの語義は関連しているのだろうか.

答えは Yes .深く関連している.英語 romance は古フランス語 romanz からの借用語で,後者は俗ラテン語 *Rōmānicē 「ロマンス語で」,さらにラテン語 Rōmānicus 「ローマの」に遡るとされる.古フランス語では,この語はラテン語に対してラテン語から発達した土着語であるフランス語を指す表現として用いられた.この土着のフランス語 ( = Romance ) で書かれた土着の文学は騎士道,恋愛,冒険,空想,超自然を主題とした緩やかなまとまりを示しており,新しい文学ジャンルを発達させることになった.こうして「ロマンス」は,ラテン語から派生した土着語を指すとともに,同時にそれで書かれた中世の独特な文学を指すことになった.

文学ジャンルとしてのロマンスは12世紀半ばにフランスで生まれたが,英語に入ってきたのは1世紀以上も遅れてのことである.この遅れは,ノルマン征服によってイングランドにおける英語の社会的地位が下落し,書き言葉としての英語が再び復活するまでにしばらく時間がかかったことによる.イングランドでは英語より先にラテン語,フランス語,アングロ・ノルマン語によるロマンス作品が生まれており,後にこれら先発の作品を翻訳するという形で英語のロマンスが登場してきた.こうして13世紀後半から15世紀にかけて英語のロマンス作品が広く著わされることとなったが,ロマンスの流行は近代に入って衰退する.しかし,ロマンスはジャンルとして廃れることはなく脈々と現在にまで受け継がれている.18世紀にはゴシック・ロマンスという形で復活を果たしたし,20世紀以降の J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, J. K. Rowling などの作品に代表されるファンタジーの要素はロマンスの型を現在に伝えている.

ロマンスの定義は難しい.慣用的な表現形式や騎士道,冒険,空想といった主題の点で共通要素をもった作品の集合体とみることはできるが,その具体的な現われは国・地域や時代とともに実に多岐にわたる.この多様性,柔軟性,個別性こそがロマンス人気の息の長さを説明しているように思われる.Chism (57) が,ロマンスの特性についての Cooper の言及を紹介している.

Helen Cooper suggests that romance is best conceived as a family, branching and evolving in different directions, rather than as manifestations or "clones of a single Platonic idea," and this family metaphor is useful because it stresses the genre's existence in time.

ロマンスは,ジャンルとして常に進化し枝葉を展開してきたからこそ,時代を超えて読者を惹きつけるのだろう.

・ Chism, Christine. "Romance." Chapter 4 of The Cambridge Companion to Medieval English Literature 1100-1500. Ed. Larry Scanlon. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 57--69.

2010-10-21 Thu

■ #542. 文学,言語学,文献学 [philology][pragmatics][linguistics][literature]

文学 ( literature ) と言語学 ( linguistics ) のあいだの距離が開いてきたということは,すでに言われるようになって久しい.また,文献学 ( philology ) が20世紀後半より衰退してきていることも,随所で聞かれる.この2点は,広く世界的にも英語の領域に限っても等しく認められるのではないか.もちろん両者は互いに深く関係している.

Fitzmaurice (267--70) がこの状況を簡潔に記しているので,まとめておきたい.

(1) 20世紀後半より,言語学は文学テクストを不自然な言葉として避けるようになった.

(2) 一方で文学は理論的な方法論を追究し,言葉そのものへの関心からは離れる傾向にあった.例えば現在の英文学の主流に新歴史主義 ( new historicism ) があるが,その基礎は英語史の知見にあるというよりは人類学の発展にある.

(3) 言語学は,逸話よりも数値を重視する方向で進んできた.

(4) 一方で文学は,数値よりも逸話を重視する方向で進んできた.

このように文学と言語学が両極化の道を歩んできたことは,当然その間に位置づけられる文献学の衰退にもつながってくる.文学と言語学の方法論をバランスよく取り入れた文献学的な研究というものが一つの目指すべき理想なのだろうが,それが難しくなってきている.もっとも,この10年くらいは上記の認識が各所で危惧をもって表明されるようになり,文学と言語学を近づけ,文献学に新たな息を吹き込むような新たな試みが出始めてきている.近年の歴史語用論 ( historical pragmatics ) の盛り上がりも,その新たな試みの一つの現われと考えられるだろう.

・ Fitzmaurice, James. "Historical Linguistics, Literary Interpretation, and the Romances of Margaret Cavendish." Methods in Historical Pragmatics. Ed. Susan Fitzmaurice and Irma Taavitsainen. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2007. 267--84.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow