2021-02-16 Tue

■ #4313. 呼格,主格,対格の関係について一考 [greetings][interjection][formula][syntax][exclamation][pragmatics][syncretism][latin][case]

昨日の記事「#4312. 「呼格」を認めるか否か」 ([2021-02-15-1]) で話題にしたように,呼格 (vocative) は,伝統的な印欧語比較言語学では1つの独立した格として認められてきた.しかし,ラテン語などの古典語ですら,第2活用の -us で終わる単数にのみ独立した呼格形が認められるにすぎず,それ以外では形態的に主格に融合 (syncretism) している.「呼格」というよりも「主格の呼びかけ用法」と考えたほうがスッキリするというのも事実である.

このように呼格が形態的に主格に融合してきたことを認める一方で,語用的機能の観点から「呼びかけ」と近い関係にあるとおぼしき「感嘆」 (exclamation) においては,むしろ対格に由来する形態を用いることが多いという印欧諸語の特徴に関心を抱いている.Poor me! や Lucky you! のような表現である.

細江 (157--58) より,統語的に何らかの省略が関わる7つの感嘆文の例を挙げたい.各文の名詞句は形式的には通格というべきだが,機能的にしいていうならば,主格だろうか対格だろうか.続けて,細江の解説も引用する.

How unlike their Belgic sires of old!---Goldsmith.

Wonderful civility this!---Charlotte Brontë.

A lively lad that!---Lord Lytton.

A theatrical people, the French?---Galsworthy.

Strange institution, the English club.---Albington.

This wish I have, then ten times happy me!---Shakespeare.

この最後の me は元来文の主語であるべきものを表わすものであるが,一人称単数の代名詞は感動文では主格の代わりに対格を用いることがあるので,これには種々の理由があるらしい(§130参照)が,ラテン語の語法をまねたことも一原因であったと見られる.たとえば,

Me miserable!---Milton, Paradise Lost, IV. 73.

は全くラテン語の Me miserum! (Ovid, Heroides, V. 149) と一致する.

引用最後のラテン語 me miserum と関連して,Blake の格に関する理論解説書より "ungoverned case" と題する1節も引用しておこう (9) .

In case languages one sometimes encounters phrases in an oblique case used as interjections, i.e. apart from sentence constructions. Mel'cuk (1986: 46) gives a Russian example Aristokratov na fonar! 'Aristocrats on the street-lamps!' where Aristokratov is accusative. One would guess that some expressions of this type have developed from governed expressions, but that the governor has been lost. A standard Latin example is mē miserum (1SG.ACC miserable.ACC) 'Oh, unhappy me!' As the translation illustrates, English uses the oblique form of pronouns in exclamations, and outside constructions generally.

さらに議論を挨拶のような決り文句にも引っかけていきたい.「#4284. 決り文句はほとんど無冠詞」 ([2021-01-18-1]) でみたように,挨拶の多くは,歴史的には主語と動詞が省略され,対格の名詞句からなっているのだ.

語用的機能の観点で関連するとおぼしき呼びかけ,感嘆,挨拶という類似グループが一方であり,歴史形態的に区別される呼格,主格,対格という相対するグループが他方である.この辺りの関係が複雑にして,おもしろい.

・ 細江 逸記 『英文法汎論』3版 泰文堂,1926年.

・ Blake, Barry J. Case. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2021-01-18 Mon

■ #4284. 決り文句はほとんど無冠詞 [greetings][interjection][formula][syntax][article][exclamation][pragmatics][christmas]

正式な I wish you a merry Christmas! という挨拶を省略すると Merry Christmas! となり,I wish you a good morning. を省略すると Good morning! となる.身近すぎて気に留めることもないかもしれないが,挨拶のような決り文句 (formula) を名詞句へ省略する場合には,冠詞を切り落とすことが多い.前置詞句などを伴うケースで A merry Christmas to you! のように冠詞が残ることもあり,水を漏らさぬルールではないものの,決り文句性が高ければ高いほど冠詞まで含めて省略されるようだ.感嘆句的な Charming couple!, Dirty place!, Excellent meal!, Poor thing!, Good idea!, Lovely evening! とも通じ合うし,その他 Cigarette?, Good flight?, Next slide? などの疑問句にも通じる冠詞の省略といえる.代表的な決り文句を,Quirk et al (§11.54) より一覧しよう.

GREETINGS: Good morning, Good afternoon, Good evening <all formal>; Hello; Hi <familiar>

FAREWELLS: Goodbye, Good night, All the best <informal>, Cheers, Cheerio <BrE, familiar>, See you <familiar>, Bye(-bye) <familiar>, So long <familiar>

INTRODUCTIONS: How do you do? <formal>, How are you?, Glad to meet you, Hi <familiar>

REACTION SIGNALS:

(a) assent, agreement: Yes, Yeah /je/; All right, OK <informal>, Certainly, Absolutely, Right, Exactly, Quite <BrE>, Sure <esp AmE>

(b) denial, disagreement: No, Certainly not, Definitely not, Not at all, Not likely

THANKS: Thank you (very much), Thanks (very much), Many thanks, Ta <BrE slang>, Thanks a lot, Cheers <familiar BrE>

TOASTS: Good health <formal>, Your good health <formal>, Cheers <familiar>, Here's to you, Here's to the future, Here's to your new job

SEASONAL GREETINGS: Merry Christmas, Happy New Year, Happy Birthday, Many happy returns (of your birthday), Happy Anniversary

ALARM CALLS: Help! Fire!

WARNINGS: Mind, (Be) careful!, Watch out!, Watch it! <familiar>

APOLOGIES: (I'm) sorry, (I beg your) pardon <formal>, My mistake

RESPONSES TO APOLOGIES: That's OK <informal>, Don't mention it, Not matter <formal>, Never mind, No hard feelings <informal>

CONGRATULATIONS: Congratulations, Well done, Right on <AmE slang>

EXPRESSIONS OF ANGER OR DISMISSAL (familiar; graded in order from expressions of dismissal to taboo curses): Beat it <esp AmE>, Get lost, Blast you <BrE>, Damn you, Go to hell, Bugger off <BrE>, Fuck off, Fuck you

EXPLETIVES (familiar; likewise graded in order of increasing strength): My Gosh, (By) Golly, (Good) Heavens, Doggone (it) <AmE>, Darn (it), Heck, Blast (it) <BrE>, Good Lord, (Good) God, Christ Almighty, Oh hell, Damn (it), Bugger (it) <esp BrE>, Shit, Fuck (it)

MISCELLANEOUS EXCLAMATIONS: Shame <familiar>, Encore, Hear, hear, Over my dead body <familiar>, Nothing doing <informal>, Big deal <familiar, ironic>, Oh dear, Goal, Checkmate

決り文句の多くは何らかの統語的省略を経たものであり,それだけでも不規則と言い得るが,加えて様々な統語的制約が課されるという特徴もある.例えば,過去形にすることはできない,主語を別の人称に変えることはできない,間接疑問に埋め込むことができない等々の性質をもつものが多い.ただし,決り文句性というのも程度問題で,(A) happy new year! のように,不定冠詞の有無などに関して variation を残すものもあるだろうと考えている.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2011-02-28 Mon

■ #672. 構造主義的にみる中英語ロマンス [literature][romance][formula]

[2011-02-26-1], [2011-02-27-1]の記事で参照した Wittig は,中英語ロマンスの formula を機能的な単位として位置づけた研究者である.Wittig の議論には構造主義の視点が色濃く反映されており,それは特に次の2点において見られる.

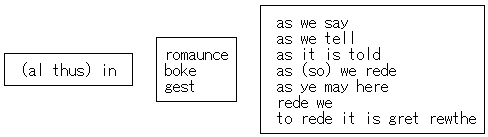

1つは,formula を "a kind of mental template, in the mind of the poet, a pattern-making device which generates a series of derivative forms" (Wittig 29) とみなしている点である.この考えによると,formula とは統合関係 ( syntagm ) を表わす「型」のことであり,そこに選択関係 ( paradigm ) にある交替可能な語句群から1つを選んで流し込んでゆくことによってある表現が実現されるとする.例えば al thus in boke as as we rede という決まり文句は,以下の「型」の各スロットに適当な語句を選択して当てはめていった結果であると考える.

もう1つすぐれて構造主義的なのは,上記のような統語レベルの型を "syntagmeme" と名付けてロマンスの構造をなす最小単位と位置づけたあとで,「交替可能な選択肢の中からの選択」という考え方をより大きな単位へと拡張してゆく点である.例えば,ロマンスには「主人公の父の死」という場面がある.この場面を構成するのは「悪者による殺害の企み」「父の登場」「敵の挑戦」「敵との戦い」「死」という一連の出来事であり,それぞれの出来事の単位は "motifeme" と呼ばれる.各 motifeme には様々な variation が用意されており,また motifeme 間の順番は決まっている.型に流し込むかのように場面が構成されてゆく.次に,「主人公の父の死」という場面それ自体がより大きな構成単位 "type-scene" となり,「主人公の追放」というもう1つの type-scene と合わさって,さらに大きな構成単位 "type-episode" となる.いずれの規模の単位においても「交替可能な選択肢の中からの選択」という同一原則が適用されており,小さい単位の積み重ねにより最終的な物語が構成されるという意味で,きわめて構造主義的な考え方といえる.

Wittig は,"Dame," he said のような単純な formula の分析から始め,より大きな単位へと分析へと積み上げてゆき,結論として中英語ロマンスに共通する2対の type-episode 連鎖を突き止めた."love-marriage" 連鎖と "separation-restoration" 連鎖である.Wittig (177) は,中英語ロマンスの形式上の定義はこの2対の連鎖が組み合わさっているということであると言い切る.

中英語ロマンスでは,love と marriage の間に必ず困難が伴い,separation (追放によるアイデンティティの喪失)と restoration (その回復)にも苦難が付随する.2対の連鎖こそが中英語ロマンスの主要な "generating forces" であり,深層構造から,鋳型へ内容物を注入しつつ,表層構造を産出してゆく原動力なのである.

最後に,Wittig の議論は壮大な speculation へと及ぶ.中英語ロマンスの聴衆の関心の根底に love-marriage と separation-restoration があったと仮定すると,それはなぜなのか.その答えの1つとして,love-marriage が象徴する女系家族制と separation-restoration が象徴する男系家族制との融和が,かれらの大きな関心事だったからではないか.

formula の言語的分析から中世イングランドの家族観へと展開する Wittig の議論を読んで,構造主義というのは,小さな部品を1つの原理で組み合わせて大きな機械を作りあげることなのかと学んだ.

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

2011-02-27 Sun

■ #671. 中英語ロマンスにおける formula の機能 [literature][romance][auchinleck][formula]

昨日の記事[2011-02-26-1]で,中英語ロマンスの言語において formula がいかに大きな割合で用いられているかを見た.ロマンスに formula が多用される背景には,いくつかの説明が提案されている.1つは,有名な The Auchinleck Manuscript のロマンス群に関連して特に言われていることで,ロンドンの写本製作所が「売れ筋本」を大量生産するために,formula を機械的に多用したという "a theory of bookshop composition and extensive textual borrowing" である (Wittig 13) .もう1つは,ロマンスは,吟遊詩人が口頭で聴衆へ伝えるという意図で作成されたものであり,語りの効果と暗唱のために繰り返しが多くなるのは自然だとする "the oral-transmission theory" である (Wittig 14) .

しかし,Wittig は上の2つの説明では説得力がないと主張する.ロマンスが中世イングランドの聴衆に受けたのは,分かりきった物語の筋や予測可能な formula を何度も聞かされることにより,物語が描く社会の現状を確認し,是認し,安心感を得ることができたからではないか.ロマンスの語り手と聞き手はともに社会の秩序に対する信頼感をもっており,ロマンスを受容することによって,その秩序を保守することに賛意を表明しているのではないか.したがって,社会が変革すればロマンスというジャンル自体も変容を迫られるか衰退することになる.ロマンスの言語は,語り手と聞き手のスタンスの言語 "a language of stance" (Wittig 46) である.Wittig のこの主張が要約された一節を引く.

If the language does not serve to carry information, what then is its primary function? In addition to carrying a minimal amount of narrative information, the language carries at least one other level of social meaning as well. That is, it carries the additional messages which are encoded within the semiology of social gestures, the language of social ritual: leave-takings, greetings, meals and banquets, marriages and knightings and tournaments. Each one of the highly ritualized events to which the formulas themselves refer is also a kind of formulaic language, a complex system of significations which is as thoroughly understood and articulated in its own culture as that culture's natural language and which is indeed a language even though it may not be a verbal one. In the romances the language of the verse refers much of the time to this second-order system, and its message-bearing function is then doubled. The language of these narratives functions not only as a medium of narrative, but as a powerful social force which supports, reinforces, and perpetuates the social beliefs and customs held by the culture, perhaps long past their normal time of decline. (Wittig 45)

上で触れた The Auckinleck Manuscript については以下のサイトが有用である.

・ The Auchinleck Manuscript : National Library of Scotland

・ Auchinleck MS Home Page

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

2011-02-26 Sat

■ #670. 中英語ロマンスにおける formula の割合 [literature][romance][statistics][formula]

中世ロマンスの言語上の大きな特徴の1つに,formula の多用がある.stock phrase とも言われ「決まり文句,常套句」を指す.formula の定義には,表現の幅を限定したきわめて狭いものから,語彙や統語のレベルでの型に適合していればよいとする広いものまであるが,多くの formula 研究は Milman Parry の次の定義から出発している.

A formula is "a group of words which is regularly employed under the same metrical conditions to express a given essential idea." (qtd in Wittig, p. 15 as from "Studies in the Epic Technique of Oral Verse-Making. I: Homer and Homeric Style." Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 41 (1930). page 80.)

formula の具体例を挙げればきりがないが,"'Dame,' he said", "that hendi knight", "feyre and free" などの短いものから,"He was a bolde man and a stowt", "And he were neuer so blythe of mode", "For to make the lady glade / That was bothe gentyll and small" などの長いものまで様々である.Wittig によれば,中英語の韻文ロマンス25作品から Parry の条件を厳密に満たす formula を含む行を抜き出したところ,以下のような結果が得られた.

| POEM | LENGTH | VERSE TYPE | FORMULA RATE |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lai le freine | 340 lines | couplet | 10% |

| Sir Landeval | 500 | couplet | 11 |

| Sir Launfal | 1044 | tail-rhyme | 16 |

| King Horn | 1644 | couplet | 18 |

| Sir Degare | 1076 | couplet | 21 |

| Havelok | 2822 | couplet | 21 |

| Sir Isumbras | 804 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Sir Amadace | 864 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Sir Perceval | 2288 | tail-rhyme | 22 |

| Horn Child | 1138 | tail-rhyme | 24 |

| Roswall and Lillian | 885 | couplet | 25 |

| Ocatvian (southern) | 1962 | tail-rhyme | 25 |

| Sir Triamour | 1719 | tail-rhyme | 25 |

| Earl of Toulous | 1224 | tail-rhyme | 26 |

| Ywain and Gawayn | 4032 | couplet | 27 |

| Sir Eglamour | 1377 | tail-rhyme | 29 |

| Squyr of Lowe Degre | 1131 | couplet | 30 |

| Lebeaus Desconus | 2131 | tail-rhyme | 30 |

| Sir Torrent | 2669 | tail-rhyme | 31 |

| Bevis of Hampton | 4332 | couplet | 34 |

| Eger and Grime | 1474 | couplet | 35 |

| Sir Degrevant | 1920 | tail-rhyme | 38 |

| Octavian (northern) | 1731 | tail-rhyme | 39 |

| Floris and Blancheflur | 1083 | couplet | 41 |

| Emare | 1030 | tail-rhyme | 42 |

平均をとると,各テキストを構成する行数の26.56%が formula を含んでいることになる.couplet では平均が24.82%,tail-rhyme では27.93%だが,大差はない.また,テキストの長さと formula 行の割合には強い相関はない.Wittig の研究では,Arthur,Troy,Alexander ものなどの "cycle" は含まれていない.参照テキストを限定し,定義を厳密にし,あくまで低めに抑えられた数え上げなので,定義を緩くすれば相当に数値が上がるはずだという.

ロマンスのテキストの約1/4が formula から成っているとすると,聴衆にとって次にどのような文言が現われるかは予測可能ということになる.また,ロマンスは物語としての筋もおよそ決まっているので,聴衆にとって「新情報」を得る機会は非常に少ないと考えられる.では,そのようなロマンスが中世に大流行したのはなぜか.聴衆はロマンスに何を期待していたのだろうか.

・ Wittig, Susan. Stylistic and Narrative Structures in the Middle English Romances. Austin and London: U of Texas P, 1978.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow