2026-02-01 Sun

■ #6124. 「すべての文字は黙字である」 --- silent letter という用語を使うべきか [silent_letter][terminology][spelling][orthography][metaphor][conceptual_metaphor][medium][writing]

本ブログでは doubt の <b> や sign の <g> などを話題にするときに黙字 (silent_letter) という用語を当たり前のように使ってきた.分かりやすく便利な用語である.しかし,これは不適格かつ不正確な用語であるとして,使用しない綴字論者もいる.

この用語のどこに問題があるのかを探っていきたいと思うのだが,まずは Carney の "2.6.5 Auxiliary, inert and empty letters" と題する節の冒頭を引くところから始めたい (40) .

All letters are 'silent', but some are more silent than others

Opinions are sharply divided on whether to allow the use of 'silent letters' in a description of English orthography so as to cater for spellings such as the <b> in debt, doubt. If we are to find our way in this controversy, we clearly need to clarify our terminology. The term 'silent letters' is an extension of a metaphor commonly used in the teaching of reading, where letters are often supposed to 'speak' to the reader. When a simple vowel letter, as the <a> in latent has its long value /eɪ/, 'the vowel says its name'. A commonly-used classroom rule for reading vowel digraphs, such as <oa>, <ea>, is: 'when two vowels go walking, it's the first that does the talking' --- a comment on the greater phonetic transparency of the first element in a complex graphic unit. But, as Albrow (1972: 11) pints out, all letters are silent: 'the sounds are not written and the symbols are not sounded; the two media are presented as parallel to each other'. He suggests the term 'dummy letters' for letters with no direct phonetic counterpart but, as far as possible, tries to do without them in his analysis.

Albrow の言い分は「文字は発声しない,ゆえにすべての文字は定義上黙字だ」ということだろう.これはある種のジョークのようにも聞こえるが,この「文字は発声する」という概念メタファーが,表音文字であるアルファベットという文字種を使う者の心に深く刻み込まれていることを理解しておくことは,実は極めて重要である.というのは,文字や綴字の議論をするに当たっては,発音と文字,話し言葉と書き言葉が,原則として異なるメディアであることを強く認識しておく必要があるからだ.両メディアは,言語使用者が様々な方法で互いに連絡させ合おうとしているのは事実だ.しかし,それは本質的に異なる2つのメディアを関わらせようという営みなのであり,常にうまく行くわけではない.むしろ,対応関係がうまく行かないのが当然だという立場からスタートしてみるほうが有益かもしれないのだ.

silent letter という用語については,今後も考え続けていく.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Albrow, K.H. The English Writing System: Notes toward a Description. London: Longman, 1972.

2026-01-31 Sat

■ #6123. salmon の第1母音 [vowel][spelling_pronunciation_gap][l][silent_letter][mond]

先日の記事「#6118. salmon の l はなぜ発音されないのですか? --- mond の質問」 ([2026-01-26-1]) で,salmon の発音と綴字の関係について取り上げた.この単語は英米両変種ともに /ˈsæmən/ と発音され,l が黙字となるのもさることながら,残された母音が /æ/ であることも不思議である.

Carney (249) によると,「#5924. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Carney にみられる「伝統的な」見解」 ([2025-07-16-1]) で引用した1段落の後に,次のような段落が続く.

The string <al> is found as a spelling of /ɑː/ (half, calm, etc.) and of /ɔː/ (talk, walk, etc.) in some very common words. It is also a nonce spelling of /æ/ in salmon. The <l> in palm can only be considered an inert representation of /l/ (as both 'part of hand' and 'tree'): cf. palmary, palmic, palmiferous.

引用に挙げられている half やその他 calf なども,米音としては /hæf/, /kæf/ となり salmon と平行的だが,英音としては /hɑːf/, /kɑːf/ となる.salmon は英米ともに /æ/ を示す点でユニークな例ということになる.

salmon の /æ/ の由来については議論があり,中英語の短母音 ă から発したと考えられれば素直なのだが,長母音 [a:] の可能性も完全には否定できないようだ.MED の見出しでは,実際 sāmŏun が第1の綴字として掲げられている.Dobson (Vol. 2, §62) に次のようにある.

Salmon (ME sa(w)mon, &c.), which retains [æ] in PresE, has ME ă in Coles (who gives the 'phonetic spelling' sam-mun) followed by Young; so probably Strong, whose spelling is samon (but this may perhaps mean ME ā). It is not clear what Cooper's pronunciation was; he includes the word in a list of those which have silent l and fails to mark it with a dagger (thereby showing that it has not got [ɒ:] < ME au), but it is not certain that it has ME ă (as is probable) rather than [a:] < ME au (which is the probable pronunciation of the other words which are left unmarked). WSC-RS includes salmon in a list of words in which al is pronounced au, but this list is merely an unintelligent copy of Cooper's and it is doubtful whether we should assume from it that salmon had [ɒ:].

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2026-01-27 Tue

■ #6119. falcon の l は発音されるかされないか [sobokunagimon][notice][l][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][emode][renaissance][french][latin][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eebo][pronunciation]

昨日の記事「#6118. salmon の l はなぜ発音されないのですか? --- mond の質問」 ([2026-01-26-1]) では,salmon (鮭)の黙字 l の背景にある語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の問題を取り上げました.今回は,その関連で,よく似た経緯をたどりながらも現代では異なる結果となっている falcon (ハヤブサ)について話しをしましょう.

falcon も salmon と同様,ラテン語 (falcōnem) に由来し,古フランス語 (faucon) の諸形態を経て中英語に入ってきました.したがって,当初は英語でも l の文字も発音もありませんでした.ところが,16世紀にラテン語綴字を参照して <l> の綴字が人為的に挿入されました.ここまでは salmon とまったく同じ道筋です.

しかし,現代英語の標準的な発音において,salmon の <l> が黙字であるのに対し,falcon の l は /ˈfælkən/ や /ˈfɔːlkən/ のように,綴字通りに /l/ と発音されるのが普通です.これは,綴字の発音が引力となって発音そのものを変化させた事例となります.

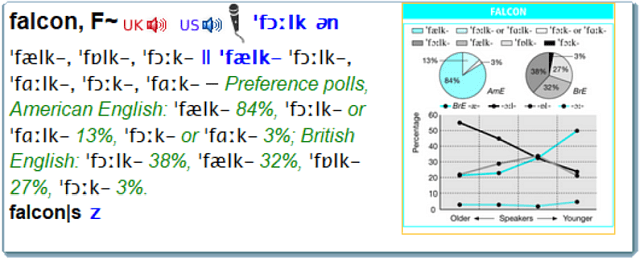

ところが,事態はそう単純ではありません.現代の発音実態を詳しく調べてみると,興味深い事実が浮かび上がってきます.LPD3 に掲載されている,英米の一般話者を対象とした Preference Poll の結果を見てみましょう.

圧倒的多数が /l/ を発音していますが,英米ともに3%ほどの話者は,現在でも /l/ を響かせない /ˈfɔːkən/ などの古いタイプの発音を使用していることが確認されます.この場合の <l> は黙字となります.さらに興味深いのは,CEPD17 の記述です.この辞書には,特定のコミュニティにおける慣用についての注釈があります.

Note: /ˈfɔː-/ is the usual British pronunciation among people who practise the sport of falconry, with /ˈfɔː-/ and /ˈfɔːl-/ most usual among them in the US.

鷹匠の間では,イギリスでは /l/ を発音しない形が普通であり,アメリカでもその傾向が見られるというのです.専門家の間では,数世紀前の伝統的な発音が「業界用語」のように化石化して残っているというのは興味深い現象です.

では,歴史的に見てこの <l> の綴字はいつ頃定着したのでしょうか.Hotta and Iyeiri では,EEBO corpus (Early English Books Online) を用いて,初期近代英語期における falcon の綴字変異を詳細に調査しました.その調査によれば,単数形・複数形を含めて,以下のような37通りもの異形が確認されました (147) .<l> の有無に注目してご覧ください.

falcon, falcons, faulcon, faucon, fawcons, faucons, fawcon, faulcons, falkon, falcone, faukon, faulcone, faukons, falkons, faulcones, faulkon, faulkons, falcones, faulken, fawlcon, fawkon, faucoun, fauken, fawcoun, fawken, falken, fawkons, fawlkon, falcoun, faucone, faulcens, faulkens, faulkone, fawcones, fawkone, fawlcons, fawlkons

まさに百花繚乱の様相ですが,時系列で分析すると明確な傾向が見えてきます.論文では次のようにまとめています (152) .

FALCON is one of the most helpful items for us in that it occurs frequently enough both in non-etymological spellings without <l> and etymological spellings with <l>. The critical point in time for the item was apparently the middle of the sixteenth century. Until the 1550s and 1560s, the non-etymological type (e.g., <faucon> and <fawcon>) was by far the more common form, whereas in the following decades the etymological type (e.g., <faulcon> and <falcon>) displaced its non-etymological counterpart so quickly that it would be the only spelling in effect at the end of the century.

つまり,16世紀半ば(1550年代~1560年代)が転換点でした.それまでは faucon のような伝統的な綴字が優勢でしたが,その後,急速に falcon などの語源的綴字が取って代わり,世紀末にはほぼ完全に置き換わったのです.

salmon と falcon.同じ時期に同じような動機で l が挿入されながら,一方は黙字となり,他方は(専門家を除けば,ほぼ)発音されるようになった.英語の歴史は,こうした予測不可能な個々の単語のドラマに満ちています.

falcon について触れている他の記事もご参照ください.

・ 「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1])

・ 「#488. 発音の揺れを示す語の一覧」 ([2010-08-28-1])

・ 「#2099. fault の l」 ([2015-01-25-1])

・ 「#5981. 苅部恒徳(編著)『英語固有名詞語源小辞典』(研究社,2011年)」 ([2025-09-11-1])

・ Wells, J C. ed. Longman Pronunciation Dictionary. 3rd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education, 2008.

・ Roach, Peter, James Hartman, and Jane Setter, eds. Cambridge English Pronouncing Dictionary. 17th ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2006.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi and Iyeiri Yoko. "The Taking Off and Catching On of Etymological Spellings in Early Modern English: Evidence from the EEBO Corpus." Chapter 8 of English Historical Linguistics: Historical English in Contact. Ed. Bettelou Los, Chris Cummins, Lisa Gotthard, Alpo Honkapohja, and Benjamin Molineaux. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2022. 143--63.

2026-01-26 Mon

■ #6118. salmon の l はなぜ発音されないのですか? --- mond の質問 [mond][sobokunagimon][notice][l][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][emode][renaissance][french][latin][spelling_pronunciation_gap][eebo][pronunciation]

salmon はつづりに l があるのに l を発音しないことからして,16~17世紀あたりのつづりと発音の混乱が影響している臭いがします.salmonの発音と表記の歴史について教えてください.

知識共有プラットフォーム mond にて,上記の質問をいただきました.日常的な英単語に潜む綴字と発音の乖離 (spelling_pronunciation_gap) に関する疑問です.

結論から言えば,質問者さんの推察は当たっています.salmon の l は,いわゆる語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の典型例であり,英国ルネサンス期の学者たちの古典回帰への憧れが具現化したものです.

hellog でもたびたび取り上げてきましたが,英語の語彙の多くはフランス語を経由して入ってきました.ラテン語の salmō (acc. salmōnem) は,古フランス語で l が脱落し saumon などの形になりました.中英語期にこの単語が借用されたとき,当然ながら英語でも l は綴られず,発音もされませんでした.当時の文献を見れば,samon や samoun といった綴字が一般的だったのです.

ところが,16世紀を中心とする初期近代英語期に入ると,ラテン語やギリシア語の素養を持つ知識人たちが,英語の綴字も由緒正しいラテン語の形に戻すべきだ,と考え始めました.彼らはフランス語化して「訛った」綴字を嫌い,語源であるラテン語の形を参照して,人為的に文字を挿入したのです.

debt や doubt の b,receipt の p,そして salmon の l などは,すべてこの時代の産物です.これらの源的綴字は,現代英語に多くの黙字 (silent_letter) を残すことになりました.

しかし,ここで英語史のおもしろい(そして厄介な)問題が生じます.綴字が変わったとして,発音はどうなるのか,という問題です.綴字に引きずられて発音も変化した単語(fault や assault など)もあれば,綴字だけが変わり発音は古いまま取り残された単語(debt や doubt など)もあります.salmon は後者のグループに属しますが,この綴字と発音のねじれた対応関係が定着したのは,いつ頃のことだったのでしょうか.

回答では,EEBO corpus (Early English Books Online) のコーパスデータを駆使して,salmon の綴字に l が定着していく具体的な時期(10年刻みの推移)をグラフで示しました.調査の結果,1530年代から1590年代にかけてが変化の中心期だったことが分かりました.1590年代以降,現代の対応関係が確立したといってよいでしょう.

回答では,1635年の文献に見られる,あるダジャレの例も紹介しています.また,話のオチとして「鮭」そのものではありませんが,この単語に関連するある細菌(食中毒の原因として有名なアレです)の名前についても触れています.

なぜ salmon は l を発音しないままなのか.その背後にある歴史ドラマと具体的なデータについては,ぜひ以下のリンク先の回答をご覧ください.

・ Hotta, Ryuichi and Iyeiri Yoko. "The Taking Off and Catching On of Etymological Spellings in Early Modern English: Evidence from the EEBO Corpus." Chapter 8 of English Historical Linguistics: Historical English in Contact. Ed. Bettelou Los, Chris Cummins, Lisa Gotthard, Alpo Honkapohja, and Benjamin Molineaux. Amsterdam: Benjamins, 2022. 143--63.

2025-07-18 Fri

■ #5926. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Dobson による言及 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode][orthoepy]

[2025-07-15-1], [2025-07-16-1], [2025-07-17-1]に続いての話題.初期近代英語期の正音学者の批判的分析といえば,まず最初に当たるべきは Dobson である.案の定 could の <l> についてある程度の紙幅を割いてしっかりと記述がなされている.Dobson (Vol. 2, §4) を引用する.

Could: the orthoepists record four main pronunciations, [kʌuld], [ku:ld], [kʊd], and [kʌd]. The l of the written form is due to the analogy of would and should, and it is clear that pronunciation was similarly affected. The transcriptions of Smith, Hart, Bullokar, Gil, and Robinson show only forms with [l], and Hodges gives a form with [l] beside one without it. Tonkis says that could is 'contracted' to cou'd, from which it would appear that the [l] was pronounced in more formal speech. Brown in his 'phonetically spelt' list writes coold beside cud) for could, and the 'homophone' lists from Hodges onwards put could by cool'd. Poole's rhymes show that he pronounced [l]. Tonkis gives the first evidence of the form without [l]; he is followed by Hodges, Wallis, Hunt, Cooper, and Brown. The evidence of other orthoepists is of uncertain significance.

一昨日,Shakespearean 学者2名にこの件について伺う機会があったのだが,could の /l/ ありの発音があったことには驚かれていた.上記の Dobson の記述によると,初期近代英語期のある時期には,むしろ /l/ の響く発音のほうが一般的だったとすら解釈できることになる.この時代の発音の実態の割り出すのは難しいが,ひとまずは Dobson の卓越した文献学的洞察に依拠して理解しておこう.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2025-07-17 Thu

■ #5925. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Jespersen による言及 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode][orthoepy]

[2025-07-15-1], [2025-07-16-1]に続いての話題.could の <l> は /l/ として発音されたことがあるかという問題に迫っている.Jespersen (§10.453) によると,初期近代英語期には発音されたとする記述がある.具体的には,正音学者 Hart と Gill に,その記述があるという.

10.453. /l/ has also been lost in a few generally weak-stressed verbal forms should, weak [ʃəd], now stressed [ˈʃud] would [wəd, ˈwud] . could [kəd, ˈkud]. The latter verb owes its l, which was pronounced in early ModE, to the other verbs. H 1569 [= Hart, Orthographie] has /kuld, ʃuld, (w)uld/, G 1621 [= A Gill, Logonomia] /???ku-ld, shu-d, wu-d/.

該当する時代がちょうど Shakespeare の辺りなので,Crystal の Shakespeare 発音辞典を参照してみると,次のように /l/ が実現されないものとされるものの2通りの発音が並記されている.

could / ~est v

=, kʊld / -st

複数の先行研究,また同時代の記述にも記されているということで,少なくとも could の <l> が発音されるケースがあったことは認めてよいだろう.引き続き,どのようなレジスターで発音されることが多かったのかなど,問うべき事項は残っている.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Crystal, David. The Oxford Dictionary of Original Shakespearean Pronunciation. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

2025-07-16 Wed

■ #5924. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- Carney にみられる「伝統的な」見解 [silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][etymological_respelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode]

昨日の記事「#5922. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- 『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述をめぐって」 ([2025-07-15-1]) に引き続き,could の <l> の話題.Carney (249) によると,この <l> が /l/ と発音されたことはないと断言されている.断言であるから,昨日の記事で示した OED が間接的に取っている立場とは完全に異なることになる.

<l> is an empty letter in the three function words could, should and would. In should and would the original /l/ of ME sholde, wolde was lost in early Modern English, and could, which never had an /l/, acquired its current spelling by analogy. So, this group of modals came to have a uniform spelling.

これはある意味で「伝統的な」見解といえるのかもしれない.しかし,which never had an /l/ という言い方は強い.この強い表現は,何らかの根拠があってのことなのだろうか.それは不明である.

doubt の <b> が発音されたことは一度もないという,どこから出たともいえない類いの言説と同様に,語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の事例では,必ずしも盤石な根拠なしに,このような強い表現がなされることがあるのかもしれない.とすれば,「伝統」というよりは「神話」に近いかもしれない.

ちなみに,英語綴字史を著わしている Scragg (58) や Upward and Davidson (186) にも当たってみたが,could の <l> の挿入についての記述はあるが,その発音については触れられていない.

私自身も深く考えずに「伝統的」の表現を使ってきたものの,これはこれでけっこう怪しいのかもしれないな,と思う次第である.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2025-07-15 Tue

■ #5923. could の <l> は発音されたか? --- 『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述をめぐって [hee][silent_letter][analogy][auxiliary_verb][sobokunagimon][etymological_respelling][orthoepy][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling_pronunciation][emode]

『英語語源ハンドブック』の記述について,質問をいただきました.ハンドブックの can/could 項目に次のようにあります.

can という語形は古英語期の直説法1・3人称現在単数形 can に由来.3人称単数過去形は cuðe で,これに基づく coud(e) のような l の入らない語形もかなり遅い時期まで記録されている.一方,現在標準となっている could という綴りは,should や would との類推により l が加えられてできたもので,中英語期末期以降使われている.語源的裏付けのない l は綴りに加えられたものの,発音には影響を与えなかった.

一方,質問者に指摘によると,OED の can の語源欄に,次のような記述があるとのことです.

Past tense forms with -l- . . . appear in the second half of the 15th cent. by analogy with should and would, prompted by an increasingly frequent loss of -l- in those words . . . . The -l- in could (as well as in should and would) is always recorded as pronounced by 16th-cent. orthoepists, reflecting the variant preferred in more formal use, and gradually disappears from pronunciation over the course of the 17th cent.

この記述に従えば,could の <l> は would, should からの類推により挿入された後に,文字通りに /l/ としても発音されたことがあったと解釈できます.つまり,挿入された <l> が,かつても現代標準英語のように無音だったと,すなわち黙字 (silent_letter) だったと断じることはできないのではないかということです.

基本的には,質問者のご指摘の通りだと考えます.ただし,考慮すべき点が2点ありますので,ここに記しておきたいと思います.(1) は英語史上の事実関係をめぐる議論,(2) はハンドブックの記述の妥当性をめぐる議論です.

(1) OED の記述が先行研究を反映しているという前提で,could の <l> が16世紀には必ず発音されていたものとして正音学者により記録されているという点については,ひとまず認めておきます(後に裏取りは必要ですが).ただし,そうだとしても,正音学者の各々が,当時の発音をどこまで「正しく」記述しているかについて綿密な裏取りが必要となります.正音学者は多かれ少なかれ規範主義者でもあったので,実際の発音を明らかにしているのか,あるいはあるべき発音を明らかにしているのかの判断が難しいケースがあります.おそらく記述通りに could の <l> が /l/ と発音された事実はあったと予想されますが,本当なのか,あるいは本当だとしたらどのような条件化でそうだったのか等の確認と調査が必要となります.

(2) ハンドブック内の「語源的裏付けのない l は〔中略〕発音には影響を与えなかった」という記述についてですが,これは could の <l> に関する伝統的な解釈を受け継いだものといってよいと思います.この伝統的な解釈には,質問者が OED を参照して確認された (1) の専門的な見解は入っていないと予想されるので,これがハンドブックの記述にも反映されていないというのが実態でしょう.その点では「発音には影響を与えなかった」とするのはミスリーディングなのかもしれません.ただし,ここでの記述を「発音に影響を与えたことは(歴史上一度も)なかった」という厳密な意味に解釈するのではなく,「結果として,現代標準英語の発音の成立に影響を与えることにはならなかった」という結果論としての意味であれば,矛盾なく理解できます.

同じ問題を,語源的綴字の (etymological_respelling) の典型例である doubt の <b> で考えてみましょう.これに関して「<b> は発音には影響を与えなかった」と記述することは妥当でしょうか? まず,結果論的な解釈を採用するのであれば,これで妥当です.しかし,厳密な解釈を採用しようと思えば,まず doubt の <b> が本当に歴史上一度も発音されたことがないのかどうかを確かめる必要があります.私は,この <b> は事実上発音されたことはないだろうと踏んではいますが,「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) でみたように Shakespeare が劇中であえて <b> を発音させている例を前にして,これを <b> ≡ /b/ の真正かつ妥当な用例として挙げてよいのか迷います./b/ の存在証明はかなり難しいですし,不在証明も簡単ではありません.

このように厳密に議論し始めると,いずれの語源的綴字の事例においても,挿入された文字が「発音には影響を与えなかった」と表現することは不可能になりそうです.であれば,この表現を避けておいたほうがよい,あるいは別の正確な表現を用いるべきだという考え方もありますが,『英語語源ハンドブック』のレベルの本において,より正確に,例えば「結果として,現代標準英語の発音の成立に影響を与えることにはならなかった」という記述を事例ごとに繰り返すのもくどい気がします.重要なのは,上で議論してきた事象の複雑性を理解しておくことだろうと思います.

以上,考えているところを述べました.記述の正確性と単純化のバランスを取ることは常に重要ですが,バランスの傾斜は,話題となっているのがどのような性格の本なのかに依存するものであり,それに応じて記述が成功しているかどうかが評価されるべきものだと考えています.この観点から,評価はいかがでしょうか?

いずれにせよ,(1) について何段階かの裏取りをする必要があることには違いありませんので,質問者のご指摘に感謝いたします.

・ 唐澤 一友・小塚 良孝・堀田 隆一(著),福田 一貴・小河 舜(校閲協力) 『英語語源ハンドブック』 研究社,2025年.

2024-12-12 Thu

■ #5708. 2重字 <gh> の起源 --- <ch>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> と考え合わせて [grapheme][graphotactics][orthography][spelling][gh][digraph][h][consonant][silent_letter][diacritical_mark][grapheme][yogh]

昨日の記事「#5707. 2重字 <gh> の起源」 ([2024-12-11-1]) に続き,<gh> がいかにして出現したかについて.英語綴字史の古典を著わした Scragg (46--47) に,次のくだりがある.

The use of <h> as a diacritic in <ch> and <sh>, indicating that <c> and <s> have a pronunciation different from that normally expected of those consonantsa, was not new to English when <ch> was introduced from French, for <th> had earlier been used alongside <þ> (cf. footnotes to pp. 2b and 17). Both <ch> in French and <th> in English derive from Latin orthography, use of <h> as a diacritic in Latin being made possible by the disappearance of the sounds represented by <h> from the language in the late classical period. As a result of the establishment in English of diacritic <h> in <ch> and <th>, other consonant groups were formed on the same pattern. The grapheme <gh> has already been discussed (p. 23c). <wh> has a rather different history, for it began in Old English as an initial consonantal combination <hw> corresponding to /xw/. Assimilation of the group to a single voiceless consonant /ʍ/ had taken place by the late Old English period, and Middle English scribes, associating the sequence <hw> for the single phoneme with the use of <h> as a fricative marker in other graphemes, reversed the graphs to <wh>.

English scribes' incorporation into their spelling system of the grapheme <ch>, and the 'consequential' changes which resulted in the creation of <sh> and <wh>, were made possible by their knowledge of Anglo-Norman conventions.

この引用文のなかに同著内への参照が何カ所があるが,そちらを参照すると重要な記述がみつかったので,引用者による注記符号に対応させるかたちで以下に参照先の解説文を掲載する.

a I.e. <h> as a fricative marker, allowing for the fact that <sh> is historically a simplification of <sch>. (fn. 2 to p. 46)

b Latin <th> had always been recognised as an alternative to thorn by English writers; even before the Norman Conquest, foreign names were spelt with either: Elizabeth or Elizabeþ, Thomas or þomas. (fn. 2 to p. 2)

c <ȝ> was also used in Middle English for the two allophones of /j/ which occurred after a vowel: [ç] and [x]. These two sounds gave scribes considerable difficulty in Middle English; among the many graphemes representing them are the Anglo-Norman <s>, the Old English <h>, the new grapheme <ȝ>, and the last two combined as <ȝh>. In the fifteenth century, when the distinction between <ȝ> and <g> became blurred, this combination was written <gh>, and this is the sequence which has survived in a great many words in which [ç] and [x] were once heard, or still are in northern dialects, e.g. high, ought, night, bough. (fn. 2 to p. 23)

以上より,今回の話題に関連する重要な点を箇条書きすると,次の通り.

(1) <th> は古英語期にも用いられることがあった

(2) 2重字 <ch> と <th> はおおもとはラテン語正書法に由来する

(3) <h> が発音区別符(号) (diacritical_mark) として用いられるようになったのは,古典期後のラテン語で h が無音化し,<h> が解放されたから

(4) 2文字目に <h> をもつ既存の2重字のパターンが,アングロノルマン語の綴字慣習を知っていた英語写字生の手により,他へも拡大した

(5) 2文字目に <h> をもつ2重字は,(h が本来的に摩擦音なので)摩擦音を示す

<gh> を含む2重字の起源と発達が徐々に見えてきた.

・ Scragg, D. G. A History of English Spelling. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1974.

2024-12-11 Wed

■ #5707. 2重字 <gh> の起源 [graphotactics][orthography][spelling][gh][digraph][h][anglo-norman][scribe][yogh][consonant][silent_letter][diacritical_mark][grapheme][yogh]

2重字 (digraph) の <gh> については,本ブログでも gh の各記事で話題にしてきた.この2重字 <gh> については,それが表わす音価とともに,英語史上でもいろいろな論点がある.そのなかでも注目したい問題の1つに起源の問題がある.古英語では,中英語以降に典型的に <gh> が用いられる多くのケースで,<h> の1文字が使われていた.中英語になると,この環境における <h> の使用は徐々に衰退していき,代わって <gh> や <ȝ> (= yogh) が台頭してくることになる.<gh> はいったいどこから来たのだろうか.

Upward and Davidson (182) によると,2重語 <gh> はアングロノルマン写字生によってもたらされた新機軸であるという.

. . . ANorm scribes frequently replaced the OE H with GH: OE niht, ME night; OE brohte, ME broughte 'brought'. (The letter ȝ was also used: niȝt, brouȝte.) The GH represented /x/, which was pronounced [ç] after a front vowel and [x] after a back vowel, as in ME night and broughte respectively (and as also in Modern German). Although, under the influence of Chancery and the printers, this digraph has continued to be written from the ME period to the present day, the sound it represented/represents has undergone many changes.

アングロノルマン語の綴字には <ch>, <sh>, <th>, <wh> など2文字目に <h> をもつ2重字の使用が確認される.これらすべてが現代英語で見慣れているほど多く用いられていたわけではないものの,2重字 <gh> もこれらの仲間だった (cf.Anglo-Norman Dictionary) .アングロノルマン語を書き慣れた写字生や,その影響を受けた英語の写字生が,英語を書く際にも <gh> を持ち込んだということになる.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2024-07-13 Sat

■ #5556. kh の綴字をもつ単語とその外来性 [spelling][loan_word][digraph][h][digraph][silent_letter][orthography]

昨日の記事「#5555. kh の綴字」 ([2024-07-12-1]) に引き続き,2重字 (digraph) の <kh> について.Upward and Davidson (257) にまとまった記述があるので引用する.

KH

The KH spelling reflects an aspirated consonant (somewhat like [k] + [h]) or a fricative (like [x] as in Scottish loch) in the source or carrier languages, all from the Middle East or Indian subcontinent. In English, there is no difference in pronunciation between KH and K.

・ In initial position: khaki (< Hindi); khamsin 'hot wind' (< Arabic); khan (spelt caan when first borrowed in the 15th century; < a Turkic language)

- Khazi, a slang word for 'toilet' dating from the 19th century, is not, despite its spelling, of eastern origin, but probably derives from Italian or Spanish casa 'house'. It has various spellings in English (kazi, kharzie, karsey, etc.).

・ In medial position: astrakhan 'fabric' (< Russian place-name); bakhshish 'tip or bribe' (a spelling baksheesh --- see under 'K'); burkha (a spelling of burka/burqa --- see under 'K'); gymkhana (< Urdu gend-khana, altered by influence of gymnastics); kolkhoz 'collective farm in USSR' (< Russian).

・ In final position: ankh 'emblem of life' (< Egyptian 'nh); lakh '100,000' (also lac; < Hindi and Hindustani); rukh 'mythical bird' (another spelling of roc, which is the more common spelling in English; < Arabic rokh, rukhkh, Persian rukh); sheikh (< Arabic shaikh).

ほぼすべての単語が中東,インドア大陸,ロシアの諸言語に由来し,その原語の風味を保持するために,本来的には英語に馴染みのない <kh> という綴字が用いられているのだろう.書き言葉の綴字には,話し言葉の発音では標示し得ない,単語の由来を示唆する機能が部分的であれ備わっているという点が重要である.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2024-07-12 Fri

■ #5555. kh の綴字 [spelling][loan_word][digraph][h][khelf][acronym][digraph][silent_letter][orthography]

khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)では『英語史新聞』を発行するなど,英語史を振興する「hel活」 (helkatsu) を様々に展開しています.

khelf という呼称は "Keio History of the English Language Forum" の頭字語 (acronym) で,私自身の造語なのですが,日本語発音では「ケルフ」,英語発音では /kɛlf/ となるのだろうと思います.khelf の <kh> の綴字連続が見慣れないという声が寄せられましたので,英語の綴字における 2重字 (digraph) について本記事で取り上げます.

<kh> は,英語においては決して頻度の高い文字の組み合わせではありませんが,khaki (カーキ色),khan (カーン,ハーン,汗),Khmer (クメール人),Khoisan (コイサン語族),Sikh (シク教徒)などに見られ,いずれの単語でも <kh> ≡ /k/ の対応関係を示します.ただし,すべて借用語や固有名であり,英語正書法に完全に同化しているかといえば怪しいところです.Carney (221) では,<kh> に言及しつつ astrakhan (アストラカン織), gymkhana (野外競技会), khaki, khan, khedive (エジプト副王)が挙げられています.

Carney (328) では,<h> を2文字目としてもつ,子音を表わす他の2重字とともに <kh> が扱われています.関連箇所を引用しましょう.

The clusters <ch>, <ph>, <sh>, <th>, <wh>, are treated as spelling units. So are the clusters <gh>, <kh>, <rh>, but there is a difference. In the first group, the <h> has the natural function of indicating the features 'voiceless and fricative' in representing [ʧ], [f], [ʃ], [ʍ]; <th> represents only 'fricative' for both voiceless [θ] and voiced [ð]. In the group <gh>, <kh>, <rh>, the <h> is empty and arbitrary; there is some marking, however: <rh> is §Greek, <kh> is exotic.

<kh> の <h> は音声的には動機づけのない黙字 (silent_letter) といってしかるべきだが,最後に触れられているとおり,その単語が "exotic" であることを標示する機能は有しているようだ.khelf もユニークで魅惑的という意味での "exotic" な活動を目指したい.

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

2023-10-17 Tue

■ #5286. 千葉慶友会で「英語はこんなにおもしろい」をお話ししてきました [notice][voicy][heldio][keiyukai][senbonknock][sobokunagimon][silent_letter][complementation][gerund][infinitive][impersonal_verb]

先週末の10月14日(土)の午後,船橋の某所で開催された千葉慶友会の講演会にて「英語学習に役立つ英語史 --- 英語はこんなにおもしろい」をお話ししました.事前の準備から当日のハイブリッド開催の運営,そして講演会後の懇親会のアレンジまで,スタッフの皆さんにはたいへんお世話になり,感謝しております.ありがとうございました.とりわけ懇親会では千葉慶友会内外からの参加者の皆さんと直接お話しすることができ,実に楽しい時間でした.

90分ほどの講演の後,その場で続けて Voicy heldio の生放送をお送りしました.前もって運営スタッフの方々と打ち合わせしていた企画なのですが,事前に参加予定者より「英語に関する素朴な疑問」を寄せていただき,当日の投げ込み質問も合わせて,私が英語史の観点から回答していくのを heldio でライヴ配信しようというものです.

そちらの様子は,昨日 heldio のアーカイヴにて「#868. 千葉慶友会での「素朴な疑問」コーナー --- 2023年10月14日の生放送」として配信していますので,お時間のあるときにお聴きください(1時間弱の長尺となっています).

6件ほどの素朴な疑問にお答えしました.以下に分秒を挙げておきますので,聴く際にご利用ください.

(1) 02:25 --- 外国語からカタカナに音訳するときに何かルールはありますか.この質問をする理由は,例えば本によって「フロベール」だったり「フローベール」だったりすることがあるからです.また,カタカナを英語らしく発音するコツはありますか.

(2) 14:43 --- 英語の「パラフレーズ」の歴史的遷移について,なにか参考資料をご存知でしたら教えていただければ嬉しいです.Academic Writing を勉強している途中で興味を持ちました.

(3) 21:34 --- 英単語には island など読まない文字があるのはなぜですか?

(4) 30:43 --- 世界における言語の多様性の問題,および諸言語は今後どのように展開(分岐か収束か)していくのかという問題

(5) 39:05 --- 動詞によって目的語に -ing をとるか to 不定詞をとるかが決まっているのはなぜですか?

(6) 44:05 --- なぜ英語には無生物主語構文があるのですか?

時間内に取り上げられたのは6件のみですが,他にも多くの疑問をいただいていましたので,いずれ hellog/heldio で取り上げたいと思います.

実は慶友会の講演と絡めての Voicy heldio ライブの千本ノックは初めてではありません.同様の雰囲気をさらに味わいたい方は,3ヶ月半ほど前の「#5179. アメリカ文学慶友会での千本ノック収録を公開しました」 ([2023-07-02-1]) もご訪問ください.

2023-04-01 Sat

■ #5087. 「英語史クイズ with まさにゃん」 in Voicy heldio とクイズ問題の関連記事 [masanyan][helquiz][link][silent_letter][etymological_respelling][kenning][oe][metonymy][metaphor][gender][german][capitalisation][punctuation][trademark][alliteration][sound_symbolism][goshosan][voicy][heldio]

新年度の始まりの日です.学びの意欲が沸き立つこの時期,皆さんもますます英語史の学びに力を入れていただければと思います.私も「hel活」に力を入れていきます.

実はすでに新年度の「hel活」は始まっています.昨日と今日とで年度をまたいではいますが,Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ (heldio)」にて「英語史クイズ」 (helquiz) の様子を配信中です.出題者は khelf(慶應英語史フォーラム)会長のまさにゃん (masanyan),そして回答者はリスナー代表(?)の五所万実さん(目白大学; goshosan)と私です.ワイワイガヤガヤと賑やかにやっています.

・ 「#669. 英語史クイズ with まさにゃん」

・ 「#670. 英語史クイズ with まさにゃん(続編)」

実際,コメント欄を覗いてみると分かる通り,昨日中より反響をたくさんいただいています.お聴きの方々には,おおいに楽しんでいただいているようです.出演者のお二人にもコメントに参戦していただいており,場外でもおしゃべりが続いている状況です.こんなふうに英語史を楽しく学べる機会はあまりないと思いますので,ぜひ hellog 読者の皆さんにも聴いて参加いただければと思います.

以下,出題されたクイズに関連する話題を扱った hellog 記事へのリンクを張っておきます.クイズから始めて,ぜひ深い学びへ!

[ 黙字 (silent_letter) と語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) ]

・ 「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1])

・ 「#192. etymological respelling (2)」 ([2009-11-05-1])

・ 「#1187. etymological respelling の具体例」 ([2012-07-27-1])

・ 「#580. island --- なぜこの綴字と発音か」 ([2010-11-28-1])

・ 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1])

[ 古英語のケニング (kenning) ]

・ 「#472. kenning」 ([2010-08-12-1])

・ 「#2677. Beowulf にみられる「王」を表わす数々の類義語」 ([2016-08-25-1])

・ 「#2678. Beowulf から kenning の例を追加」 ([2016-08-26-1])

・ 「#1148. 古英語の豊かな語形成力」 ([2012-06-18-1])

・ 「#3818. 古英語における「自明の複合語」」 ([2019-10-10-1])

[ 文法性 (grammatical gender) ]

・ 「#4039. 言語における性とはフェチである」 ([2020-05-18-1])

・ 「#3647. 船や国名を受ける she は古英語にあった文法性の名残ですか?」 ([2019-04-22-1])

・ 「#4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ」 ([2020-10-08-1])

[ 大文字化 (capitalisation) ]

・ 「#583. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった」 ([2010-12-01-1])

・ 「#1844. ドイツ語式の名詞語頭の大文字使用は英語にもあった (2)」 ([2014-05-15-1])

・ 「#1310. 現代英語の大文字使用の慣例」 ([2012-11-27-1])

・ 「#2540. 視覚の大文字化と意味の大文字化」 ([2016-04-10-1])

[ 頭韻 (alliteration) ]

・ 「#943. 頭韻の歴史と役割」 ([2011-11-26-1])

・ 「#953. 頭韻を踏む2項イディオム」 ([2011-12-06-1])

・ 「#970. Money makes the mare to go.」 ([2011-12-23-1])

・ 「#2676. 古英詩の頭韻」 ([2016-08-24-1])

2022-11-14 Mon

■ #4949. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第21回「「マジック e」って何?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][final_e][spelling][vowel][terminology][silent_letter][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

本日は『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の12月号の発売日です.連載「歴史で謎解き 英語のソボクな疑問」の第21回では「「マジック e」って何?」という疑問を取り上げています.

綴字上 mate と mat は語末に <e> があるかないかの違いだけですが,発音はそれぞれ /meɪt/, /mæt/ と母音が大きく異なります.母音が異なるのであれば,綴字では <a> の部分に差異が現われてしかるべきですが,実際には <a> の部分は変わらず,むしろ語尾の <e> の有無がポイントとなっているわけです.しかも,その <e> それ自体は無音というメチャクチャぶりのシステムです.多くの英語学習者が,学び始めの頃に一度はなぜ?と感じたことのある話題なのではないでしょうか.

一見するとメチャクチャのようですが,類例は多く挙げられます.Pete/pet, bite/bit, note/not, cute/cut などの母音を比較してみてください.ここには何らかの仕組みがありそうです.少し考えてみると,語末の <e> の有無がキューとなり,先行する母音の音価が定まるという仕組みになっています.いわば魔法のような「遠隔操作」が行なわれているわけで,ここから magic e の呼称が生まれました.

今回の連載記事では,なぜ magic e という間接的で厄介な仕組みが存在するのか,いかにしてこの仕組みが歴史の過程で生まれてきたのかを易しく解説します.本ブログでもたびたび取り上げてきた話題ではありますが,連載記事では限りなくシンプルに説明しています.ぜひ雑誌を手に取ってみてください.

関連して以下の hellog 記事を参照.

・ 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])

・ 「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1])

・ 「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1])

・ 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸」 ([2020-02-23-1])

・ 「#4883. magic e という呼称」 ([2022-09-09-1])

2022-10-22 Sat

■ #4926. yacht の <ch> [dutch][loan_word][silent_letter][consonant][spelling_pronunciation][metathesis][phoneme][grapheme][spelling_pronunciation_gap][spelling][consonant][phonology][orthography][digraph][eebo]

学生から <ch> が黙字 (silent_letter) となる珍しい英単語が4つあるということを教えてもらった(貴重な情報をありがとう!).drachm /dræm/, fuchsia /ˈfjuːʃə/, schism /sɪzm/, yacht /jɑt/ である.典拠は「#2518. 子音字の黙字」 ([2016-03-19-1]) で取り上げた磯部 (7) である.

今回は4語のうち yacht に注目してみたい.この語は16世紀のオランダ語 jaght(e) を借用したもので,OED によると初例は以下の文である(cf. 「#4444. オランダ借用語の絶頂期は15世紀」 ([2021-06-27-1])).初例で t の子音字がみられないのが気になるところではある.

a1584 S. Borough in R. Hakluyt Princ. Navigations (1589) ii. 330 A barke which was of Dronton, and three or foure Norway yeaghes, belonging to Northbarne.

英語での初期の綴字(おそらく発音も)は,原語の gh の発音をどのようにして取り込むかに揺れがあったらしく,様々だったようだ.OED の解説によると,

Owing to the presence in the Dutch word of the unfamiliar guttural spirant denoted by g(h), the English spellings have been various and erratic; how far they represent varieties of pronunciation it is difficult to say. That a pronunciation /jɔtʃ/ or /jatʃ/, denoted by yatch, once existed seems to be indicated by the plural yatches; it may have been suggested by catch, ketch.

<t> と <ch> が反転した yatch とその複数形の綴字を EEBO で検索してみると,1670年代から1690年代までに50例ほど上がってきた.ちなみに,このような綴字の反転は中英語では珍しくなく,とりわけ "guttural spirant" が関わる場合にはよく見られたので,ある意味ではその癖が初期近代英語期にまではみ出してきた,とみることもできるかもしれない.

yatch の発音と綴字については,Dobson (371) が次のように言及している.

Yawt or yatch 'yacht' are two variant pronunciations which are well evidenced by OED; the former is due to the identification of the Dutch spirant [χ] with ME [χ], of which traces still remained when yacht was adopted in the sixteenth century, so that it was accommodated to the model of, for example, fraught and developed with it, while OED suggests that the latter is due to analogy with catch and ketch---it is certainly due to some sort of corrupt spelling-pronunciation, in the attempt to accommodate the word to native models.

<t> と <ch> の綴字上の反転と,それに続く綴字発音 (spelling_pronunciation) の結果生み出された yacht の妙な異形ということになる.

・ 磯部 薫 「Silent Consonant Letter の分析―特に英語史の観点から見た場合を中心として―」『福岡大学人文論叢』第5巻第1号, 1973年.117--45頁.

・ Dobson, E. J. English Pronunciation 1500--1700. 2nd ed. 2 vols. Oxford: OUP, 1968.

2022-09-09 Fri

■ #4883. magic e という呼称 [oed][final_e][spelling][vowel][terminology][mulcaster][walker][silent_letter][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

take, meme, fine, pope, cute などの語末の -e は,それ自体は発音されないが,先行する母音を「長音」で読ませる合図として機能する.このような用法の e は magic e (マジック e)と呼ばれる.魔法のように他の母音の発音を遠隔操作してしまうからだろう.英語教育・学習上の用語としてよく知られている.

magic e の働きや歴史の詳細は hellog より以下の記事を参照されたい.

・ 「#1289. magic <e>」 ([2012-11-06-1])

・ 「#979. 現代英語の綴字 <e> の役割」 ([2012-01-01-1])

・ 「#1827. magic <e> とは無関係の <-ve>」 ([2014-04-28-1])

・ 「#1344. final -e の歴史」 ([2012-12-31-1])

・ 「#2377. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (1)」 ([2015-10-30-1])

・ 「#2378. 先行する長母音を表わす <e> の先駆け (2)」 ([2015-10-31-1])

・ 「#3954. 母音の長短を書き分けようとした中英語の新機軸」 ([2020-02-23-1])

今回は magic e という呼称そのものに焦点を当てたい.OED の magic, adj. (and int.) のもとに追い込み見出しが立てられている.

magic e n. (also with capital initials) (chiefly in primary school literacy teaching) a silent e at the end of a word or morpheme following a consonant, which lengthens the preceding vowel and consequently appears to transform its sound; as the e in hope, lute, casework, etc.

Cf. silent adj. 3c.

1918 Primary Educ. Mar. 183/2 Let us see how the a will sound after magic e is fastened on mat. (Write mate on board. Pronounce.) You see what trick he did. He changed short a into long a.

2005 L. Wendon & L. Holt Letterland: Adv. Teacher's Guide (2009) ii. 58 It was recommended that children play-act the Magic e's function in tap and tape.

初出は100年ほど前の教育学雑誌となっている.19世紀や18世紀には遡らない,比較的新しめの表現ではないかと予想していたが,当たったようだ.

上記で Cf. として挙げられている silent, adj. and n. を参照してみると,3c の項に "silent e" に関する記述があった.

c. Of a letter: written but not pronounced. Cf. mute adj. 4b, magic e n. at magic adj. Compounds.

Sometimes designating a letter whose absence would have no impact on the pronunciation of the word, as b in doubt, and sometimes designating a letter that has a diacritic function, as final e indicating the length of the vowel of a preceding syllable, as in mute or fate.

1582 R. Mulcaster 1st Pt. Elementarie xvii. 113 Som vse the same silent e, after r, in the end, as lettre, cedre, childre, and such, where methink it were better to be the flat e, before r, as letter, ceder, childer.

1775 J. Walker Dict. Eng. Lang. sig. 4Ov Persuade, whose final E is silent, and serves only to lengthen the sound of the A in the last syllable.

1881 E. B. Tylor Anthropol. vii. 179 The now silent letters are relics of sounds which used to be really heard in Anglo-Saxon.

2017 Hispania 100 286 The letter 'h' is silent in Spanish and is often omitted by those who are not familiar with the spelling of a word.

magic e は "silent e" と同値ではない.前者は後者の特殊事例である.上の引用で Mulcaster からの初例は magic e のことを述べているわけではないことに注意が必要である.一方,2つ目の Walker からの例は,確かに magic e のことを述べている.

さらに mute, adj. and n.3 の 4b の項を覗いてみると "mute e" という呼び方もあると分かる.これは "silent e" と同値である.この呼称の初例は次の通りで,そこでは実質的に magic e のことを述べている.

1840 Proc. Philol. Soc. 3 6 It gradually was established..that when a mute e followed a single consonant the preceding vowel was a long one.

2021-09-15 Wed

■ #4524. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第7回「なぜ know や high には発音されない文字があるの?」 [notice][sobokunagimon][rensai][silent_letter][spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][link]

NHKラジオ講座「中高生の基礎英語 in English」の10月号のテキストが発売となりました.連載している「英語のソボクな疑問」も第7回となっています.今回の話題は「なぜ know や high には発音されない文字があるの?」です.

英語には綴字では書かれているのに発音されない文字というのがありますね.これは黙字 (silent_letter) と呼ばれ,英語に関する素朴な疑問の定番といってよい話題です.歴史的な由来としてはいろいろなパターンがあるのですが,最も多いのが,かつてはその文字がきちんと発音されていたというパターンです.昔の英語では,know は「クノウ」,high は「ヒーヒ」などとすべて文字通りに発音されていたのが,後に発音の変化により問題の音が消えてしまったというケースが多いのです.その一方で綴字は古いままに据え置かれ,現在までゾンビのように生き残っているというわけです.要するに,綴字が発音の変化に追いついていかなかったという悲劇ですね.

今回の話題と関連して,以下の記事を発展編として読んでみてください.英語の綴字には,本当に黙字が多いです.

・ 「#4164. なぜ know の綴字には発音されない k があるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-09-20-1])

・ 「#122. /kn/ で始まる単語」 ([2009-08-27-1])

・ 「#1095. acknowledge では <kn> が /kn/ として発音される」 ([2012-04-26-1])

・ 「#3675. kn から k が脱落する音変化の過程」 ([2019-05-20-1])

・ 「#1290. 黙字と黙字をもたらした音韻消失等の一覧」 ([2012-11-07-1])

・ 「#210. 綴字と発音の乖離をだしにした詩」 ([2009-11-23-1])

・ 「#1195. <gh> = /f/ の対応」 ([2012-08-04-1])

・ 「#2085. <ough> の音価」 ([2015-01-11-1])

・ 「#2590. <gh> を含む単語についての統計」 ([2016-05-30-1])

・ 「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1])

2021-09-06 Mon

■ #4515. <gn> の発音 [phonetics][consonant][spelling][phoneme][nasal][etymological_respelling][analogy][silent_letter]

英語の綴字 <gn> について,語頭に現われるケースについては <kn> との関係から「#3675. kn から k が脱落する音変化の過程」 ([2019-05-20-1]) の記事で簡単に触れた.16--17世紀に [gn] > [n] の過程が生じたということだった.では,語頭ではなく語中や語末に <gn> の綴字をもつ,主にフランス語・ラテン語由来の語について,綴字と発音の関係に関していかなる対応があるだろうか.Carney (247, 325) を参照してみよう.

まず <gn(e)> が語末にくる例を挙げてみよう.arraign, assign, benign, campaign, champagne, cologne, deign, design, ensign, impugn, malign, reign, resign, sign などが挙がってくる.これらの語においては <g> は黙字として機能しており,結果として <gn(e)> ≡ /n/ の関係となっている.ちなみに foreign と sovereign は非歴史的な綴字で,勘違いを含んだ語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) あるいは類推 (analogy) の産物とされる.

ただし,上記の単語群の派生語においては <g> と <n> の間に音節境界が生じ,発音上 /g/ と/n/ が別々に発音されることが多い.assignation, benignant, designate, malignant, regnant, resignation, signature, significant, signify の通り.

上記の単語群のソースとなる言語はたいていフランス語である.フランス語では <gn> は硬口蓋鼻音 [ɲ] に対応するが,英語では [ɲ] は独立した音素ではないため,英語に取り込まれる際には,近似する歯茎鼻音 [n] で代用された.[ɲ] に近い音として英語には [nj] もあり得るのだが,音素配列的に語末には現われ得ない規則なので,結果的に [n] に終着したことになる.なお,語末でなければ /nj/ で取り込まれたケースもある.例えば,cognac, lorgnette, mignonette, vignette などである.イタリア語からの Bologna, Campagna も同様.poignant については,/nj/ のほか /n/ の発音もある.

綴字について妙なことが起こったのは,フランス語 ligne に由来する line である.本来であればフランス語 signe が英語に取り込まれて <sign> ≡ /saɪn/ として定着したように,ligne も英語では <lign> ≡ /laɪn/ ほどで定着していたはずと想像される.だが,後者については英語的な綴字規則に則って <line> と綴り替えられて現在に至る.これに接頭辞をつけた動詞形にあっては <align> が普通の綴字(ただし aline もないではない)であるし,別に sign/assign というペアも見られるだけに,<line> はなんとも妙である.

line/align という語幹を共有する語の綴字上のチグハグは,ほかにも deign/disdain や feign/feint に見られる (Upward and Davidson 140) .

・ Carney, Edward. A Survey of English Spelling. Abingdon: Routledge, 1994.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2021-07-28 Wed

■ #4475. Love's Labour's Lost より語源的綴字の議論のくだり [shakespeare][mulcaster][etymological_respelling][popular_passage][inkhorn_term][latin][loan_word][spelling_pronunciation][silent_letter][orthography]

なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか,というのは英語の綴字に関する素朴な疑問の定番である.これまでも多くの記事で取り上げてきたが,主要なものをいくつか挙げておこう.

・ 「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1])

・ 「#3333. なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない b があるのか?」 ([2018-06-12-1])

・ 「#3227. 講座「スペリングでたどる英語の歴史」の第4回「doubt の <b>--- 近代英語のスペリング」」 ([2018-02-26-1])

・ 「圧倒的腹落ち感!英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由を専門家に聞きに行ったら,犯人は中世から近代にかけての「見栄」と「惰性」だった.」(DMM英会話ブログさんによるインタビュー)

doubt の <b> の問題については,16世紀末からの有名な言及がある.Shakespeare による初期の喜劇 Love's Labour's Lost のなかで,登場人物の1人,衒学者の Holofernes (一説には実在の Richard Mulcaster をモデルとしたとされる)が <b> を発音すべきだと主張するくだりがある.この喜劇は1593--94年に書かれたとされるが,当時まさに世の中で inkhorn_term を巡る論争が繰り広げられていたのだった(cf. 「#1408. インク壺語論争」 ([2013-03-05-1])).この時代背景を念頭に Holofernes の台詞を読むと,味わいが変わってくる.その核心部分は「#1943. Holofernes --- 語源的綴字の礼賛者」 ([2014-08-22-1]) で引用したが,もう少し長めに,かつ1623年の第1フォリオから改めて引用したい(Smith 版の pp. 195--96 より).

Actus Quartus.

Enter the Pedant, Curate and Dull.

Ped. Satis quid sufficit.

Cur. I praise God for you sir, your reasons at dinner haue beene sharpe & sententious: pleasant without scurrillity, witty without affection, audacious without impudency, learned without opinion, and strange without heresie: I did conuerse this quondam day with a companion of the Kings, who is intituled, nominated, or called, Dom Adriano de Armatha.

Ped. Noui hominum tanquam te, His humour is lofty, his discourse peremptorie: his tongue filed, his eye ambitious, his gate maiesticall, and his generall behauiour vaine, ridiculous, and thrasonical. He is too picked, too spruce, to affected, too odde, as it were, too peregrinat, as I may call it.

Cur. A most singular and choise Epithat,

Draw out his Table-booke,

Ped. He draweth out the thred of his verbositie, finer than the staple of his argument. I abhor such phnaticall phantasims, such insociable and poynt deuise companions, such rackers of ortagriphie, as to speake dout fine, when he should say doubt; det, when he shold pronounce debt; d e b t, not det: he clepeth a Calf, Caufe: halfe, hawfe; neighbour vocatur nebour; neigh abreuiated ne: this is abhominable, which he would call abhominable: it insinuateth me of infamie: ne inteligis domine, to make franticke, lunaticke?

Cur. Laus deo, bene intelligo.

Ped. Bome boon for boon prescian, a little scratched, 'twill serue.

第1フォリオそのものからの引用なので,読むのは難しいかもしれないが,全体として Holofernes (= Ped.) の衒学振りが,ラテン語使用(というよりも乱用)からもよく伝わるだろう.当時実際になされていた論争をデフォルメして描いたものと思われるが,それから400年以上たった現在もなお「なぜ doubt の綴字には発音しない <b> があるのか?」という素朴な疑問の形で議論され続けているというのは,なんとも息の長い話題である.

・ Smith, Jeremy J. Essentials of Early English. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2005.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow