2013-05-27 Mon

■ #1491. diglossia と borrowing の関係 [diglossia][borrowing][loan_word][register][synonym]

「#1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia」 ([2013-05-25-1]) で借用(語)について話題にしたときに,英語における illumination ? light や purchase ? buy にみられる語彙階層は,diglossia における社会言語学的な上下関係が,借用 (borrowing) という手段を通じて,語彙体系における register の上下関係へ内化したものであると指摘した.

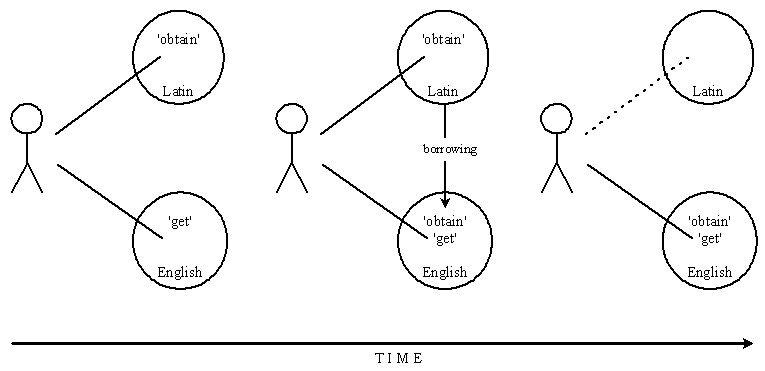

diglossia と borrowing の関係を探ることは社会言語学と理論言語学の接点を探るということにつながり,大きな研究テーマとなりうるが,この点について Hudson (56--57) が示唆的な見解を示している.Hudson は,英語本来語である get (正確には[2009-10-13-1]の記事「#169. get と give はなぜ /g/ 音をもっているのか」で示したように古ノルド語起源というべき)とラテン語に由来する obtain を取り上げ,中世イングランドの英羅語 diglossia 時代の社会的な上下関係が,借用という過程を通じて,英語語彙内の register の上下関係へ投影された例としてこれを捉えた.後に diglossia が解消されるにおよび,obtain がラテン語由来であるとの話者の記憶が薄まり,かつての diglossia に存在した上下関係の痕跡が,歴史的な脈絡を失いながら,register の上下関係として語彙体系のなかへ定着した.これを,Hudson (57) の図を参考にしながら,次のようにまとめてみた.

第1段階では,obtain と get の使い分けは,diglossia として明確に区別される2言語間における使い分けにほかならない.第2段階では,ラテン語から英語へ obtain が借用され,obtain と get の使い分けは英語内部での register による使い分けとなる.この段階では,obtain のラテン語との結びつきもいまだ感じられている.第3段階では,diglossia が解消され,obtain のラテン語との結びつきも忘れ去られている.obtain と get の使い分けは,純粋な register の差として英語語彙の内部に定着したのである.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

2013-05-26 Sun

■ #1490. diglossia は標準変種と方言の関係とは異なる [diglossia]

過去4日間にわたって取り上げてきた diglossia は,最大限に拡大解釈すれば,標準変種というものをもつ多くの言語共同体にあてはまることになる.標準変種が上位におかれ,そうでない各種方言が下位におかれ,両変種が社会的な状況に応じて,多かれ少なかれ明確に使い分けられるからだ.

しかし,ここまで拡大解釈してしまうと,言語共同体のタイポロジーを構築しようとして diglossia を提示した Ferguson の意図がまるで汲み取られないことになる.Ferguson (329) は,ある言語共同体における2変種が,以下に挙げるような domain ごとに明確に使い分けられているとき,典型的に diglossia が存在しているとみなしたのである.

| H | L | |

| Sermon in church or mosque | x | |

| Instructions to servants, waiters, workmen, clerks | x | |

| Personal letter | x | |

| Speech in parliament, political speech | x | |

| University lecture | x | |

| Conversation with family, friends, colleagues | x | |

| News broadcast | x | |

| Radio "soap opera" | x | |

| Newspaper editorial, news story, caption on picture | x | |

| Caption on political cartoon | x | |

| Poetry | x | |

| Folk literature | x |

diglossia の社会では,適切な domain で適切な変種を使わないと,話者は恥をかく,あるいは場合によっては危険にさらされることすらある.

一方で,現在のイギリスや日本などにおいてはどうか.確かに標準変種と方言変種の使い分けがあるにはあるし,適切な domain で適切な変種を使わないと恥をかく場面もあろう.しかし,両変種の差が比較的大きい話者と比較的小さい話者がいるという点が,Ferguson の挙げる典型的な diglossia 社会とは異なっている.Ferguson 自身のことばを借りれば,次の通りである.

. . . diglossia differs from the more widespread standard-with-dialects in that no segment of the speech community in diglossia regularly uses H as a medium of ordinary conversation, and any attempt to do so is felt to be either pedantic and artificial (Arabic, Greek) or else in some sense disloyal to the community (Swiss German, Creole). In the more usual standard-with-dialects situation the standard is often similar to the variety of a certain region or social group (e.g. Tehran Persian, Calcutta Bengali) which is used in ordinary conversation more or less naturally by members of the group and as a superposed variety by others. (336--37)

Ferguson の diglossia では,日常会話に上位変種を用いることはないし,用いる人はいない.現在のイギリスや日本では,日常会話に標準変種を用いることはあるし,用いる人はいる.この違いである.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Diglossia." Word 15 (1959): 325--40.

2013-05-25 Sat

■ #1489. Ferguson の diglossia 論文と中世イングランドの triglossia [diglossia][latin][french][me][loan_word][borrowing][lexicology]

過去3日間の記事 ([2013-05-22-1], [2013-05-23-1], [2013-05-24-1]) で,Ferguson の提唱した diglossia を取り上げてきた.diglossia という社会言語学的状況の定義と評価について多くの論争が繰り広げられてきたが,その議論は全体として,中世イングランドのダイナミックな言語状況を考える上で,数々の重要な観点を与えてくれたのではないか.

前の記事で触れた通り,Ferguson 自身はその画期的な論文で diglossia を同一言語の2変種の併用状況と狭く定義した.異なる2言語については扱わないと,以下のように明記している.

. . . no attempt is made in this paper to examine the analogous situation where two distinct (related or unrelated) languages are used side by side throughout a speech community, each with a clearly defined role. (325, fn. 2)

しかし,2言語(あるいはそれ以上の言語)の間にも "the analogous situation" は確かに見られ,Ferguson の論点の多くは当てはまる.ここで念頭に置いているのは,もちろん,中世イングランドにおける英語,フランス語,ラテン語の triglossia である.以下では,Ferguson の diglossia 論文に依拠して中世イングランドの triglossia を理解しようとする際に考慮すべき2つの点を指摘したい.1つは「#1486. diglossia に対する批判」 ([2013-05-23-1]) でも触れた diglossia の静と動を巡る問題,もう1つは,高位変種 (H) から低位変種 (L) へ流れ込む借用語の問題である.

Ferguson は,原則として diglossia を静的な,安定した状況ととらえた.

It might be supposed that diglossia is highly unstable, tending to change into a more stable language situation. This is not so. Diglossia typically persists at least several centuries, and evidence in some cases seems to show that it can last well over a thousand years. (332)

この静的な認識が後に批判のもととなったのだが,Ferguson が diglossia がどのように生じ,どのように解体されうるかという動的な側面を完全に無視していたわけではないことは指摘しておく必要がある.

Diglossia is likely to come into being when the following three conditions hold in a given speech community: (1) There is a sizable body of literature in a language closely related to (or even identical with) the natural language of the community, and this literature embodies, whether as source (e.g. divine revelation) or reinforcement, some of the fundamental values of the community. (2) Literacy in the community is limited to a small elite. (3) A suitable period of time, on the order of several centuries, passes from the establishment of (1) and (2). (338)

Diglossia seems to be accepted and not regarded as a "problem" by the community in which it is in force, until certain trends appear in the community. These include trends toward (a) more widespread literacy (whether for economic, ideological or other reasons), (b) broader communication among different regional and social segments of the community (e.g. for economic, administrative, military, or ideological reasons), (c) desire for a full-fledged standard "national" language as an attribute of autonomy or of sovereignty. (338)

. . . we must remind ourselves that the situation may remain stable for long periods of time. But if the trends mentioned above do appear and become strong, change may take place. (339)

上の第1の引用の3点は,中世イングランドにおいて,いかにラテン語やフランス語が英語より上位の変種として定着したかという triglossia の生成過程についての説明と解することができる.一方,第2の引用の3点は,中英語後期にかけて,(ラテン語は別として)英語とフランス語の diglossia が徐々に解体してゆく過程と条件に言及していると読める.

次に,中英語における借用語の問題との関連では,Ferguson 論文から示唆的な引用を2つ挙げよう.

. . . a striking feature of diglossia is the existence of many paired items, one H one L, referring to fairly common concepts frequently used in both H and L, where the range of meaning of the two items is roughly the same, and the use of one or the other immediately stamps the utterance or written sequence as H or L. (334)

. . . the formal-informal dimension in languages like English is a continuum in which the boundary between the two items in different pairs may not come at the same point, e.g. illumination, purchase, and children are not fully parallel in their formal-informal range of use. (334)

2つの引用を合わせて読むと,借用(語)に関する興味深い問題が生じる.diglossia の理論によれば,上位変種(フランス語)と下位変種(英語)は,社会的には潮の目のように明確に区別される.これは,原則として,潮の目を連続した一本の線として引くことができるということである.ところが,diglossia という社会言語学的状況が語彙借用という手段を経由して英語語彙のなかに内化されると,illumination ? light や purchase ? buy などの register における上下関係は確かに持ち越されこそするが,その潮の目の高低は個々の対立ペアによって異なる.英仏対立ペアをなす語彙の全体を横に並べたとき,register の上下関係を表わす潮の目の線は,社会的 diglossia の潮の目ほど明確に一本の線をなすわけではないだろう.このことは,diglossia が monoglossia へと解体してゆくとき,diglossia に存在した社会的な上下関係が,monoglossia の語彙の中にもっぱら比喩的に内化・残存するということを意味するのではないか.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Diglossia." Word 15 (1959): 325--40.

2013-05-24 Fri

■ #1488. -glossia のダイナミズム [diglossia][elf]

過去2日間の記事「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1]) と「#1487. diglossia に対する批判」 ([2013-05-23-1]) で,diglossia を巡る問題に言及した.特に昨日の記事では通時的な視点からの批判を紹介したが,通時的な視点は,中英語期のイングランドにおける diglossia とその後の diglossia の解消,さらには近代英語期以降の新たな社会言語学的状況の発展というダイナミズムを理解する上では不可欠である.ひいては,現代社会におけるリンガ・フランカとしての英語 (ELF) の役割を評価する際にも,diglossia のダイナミックな理解は多いに参考になる.

Crystal (128) の次の1節は,社会言語学で静的なものとして提案された diglossia を,英語史の動的な枠組みのなかに持ち込んだ見事な応用例と評価する.

The linguistic situation of Anglo-Norman England is, from a sociolinguistic point of view, very familiar. It is a situation of triglossia --- in which three languages have carved out for themselves different social functions, with one being a 'low-level' language, and the others being used for different 'high-level' purposes. A modern example is Tunisia, where French, Classical Arabic, and Colloquial Arabic evolved different social roles --- French as the language of (former) colonial administration, Classical Arabic primarily for religious expression, and Colloquial Arabic for everyday purposes. Eventually England would become a diglossic community, as French died out, leaving a 'two-language' situation, with Latin maintained as the medium of education and the Church . . . and English as the everyday language. And later still, the country would become monoglossic --- or monolingual, as it is usually expressed. But monolingualism is an unusual state, and in the twenty-first century there are clear signs of the reappearance of diglossia in English as it spreads around the world . . . .

ノルマン・コンクェスト以降,21世紀に至る英語の歴史を,-glossia という観点から略述すれば,(1) 英語が下位変種である triglossia,(2) 英語が下位変種である diglossia,(3) monoglossia,(4) 英語が上位変種である diglossia へと変遷してきたことになる.

「安定」「持続」には程度問題があるとはいうものの,diglossia の定義にそのような表現を含めることには,確かに違和感が残る.

・ Crystal, David. The Stories of English. London: Penguin, 2005.

2013-05-23 Thu

■ #1487. diglossia に対する批判 [diglossia]

昨日の記事「#1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer」 ([2013-05-22-1]) で,diglossia について解説した.diglossia は古今東西に広く観察され,稀な現象ではないこともあり,その概念と用語は学界で大成功を収めるに至った.

しかし,Ferguson の提案した diglossia は,次第に拡大解釈を招くようになった.昨日も述べた通り,本来の diglossia は1言語の2変種の間にみられる上下関係を指すものだったが,Fishman (Sociolinguistics 75) は異なる2言語の間にみられる上限関係をも diglossia とみなした.これにより,例えばパラグアイにおける Spanish と Guaraní のように系統的には無関係の言語どうしの関係も,diglossia の範疇に含められた.また,中世イングランドにおける Norman French と English の関係も diglossia として言及できるようになった.diglossia の概念の拡大は,この辺りまでであれば,いまだ有用性を保っているように思われる.

ところが,diglossia は,2変種あるいは3変種の併用状況を指すにとどまらず,10言語併用や20言語併用といったほとんど無意味な細分化の餌食となっていった.すべての言語共同体には各種の方言 (dialects) や使用域 (registers) があり,これらをも変種 (varieties) とみなすのであれば,どの共同体も多かれ少なかれ diglossic ということになってしまう.Ferguson は言語共同体の類型論のために diglossia という概念を提案したのだが,その意図が汲み取られずに,概念が無意味なまでに拡大されてしまった.イギリスやアメリカのように複数の社会方言の併用状況が問題となっているのであれば,diglossia というのは大げさであり,"social-dialectia" ほどでよいのではないか (Hudson 51) .

diglossia に関するもう1つの問題は,Ferguson にせよ Fishman にせよ,diglossia を静的な言語状況としてしかとらえていない点にある.なぜそのような言語状況が生じたのかという,動的,通時的な次元の考察が抜け落ちている.昨日示した Ferguson の定義には "a relatively stable language situation" とあるし,Fishman ("Prefatory Note" 3) では,"an enduring societal arrangement, extending at least beyond a three generation period" とあり,持続的,安定的な社会言語学的状況が前提とされている.しかし,昨日も中世イングランドについてみたように diglossia は破られうるものである.どのように diglossia の状況が起こり,どのように持続し,どのように解消されるのかという通時的な視点がない限り,しばしば旧植民地において上位変種を占めているヨーロッパ宗主国の言語と,現地の下位変種の言語との上下関係が固定的なものであり,解消されないものであるというイデオロギーが助長されかねない.つまり,diglossia を「安定的」と表現することは,すでにある種のイデオロギーが前提とされているのではないかということになる.少なくとも,diglossia を解消しようと運動している社会改革者にとって,diglossia の定義の中に「安定」や「持続」という表現が盛り込まれるのは我慢ならないことだろう.カルヴェ (68) は次のように述べている.

このように,ダイグロシアという概念が成功を収めたことは,それが世に問われた歴史上の時代によって説明されるような印象を受ける.アフリカ諸国の独立期に,数多くの国が複雑な言語状況に直面していた.一方では多言語状況,そして他方では旧宗主国の言語の公的側面における優位支配である.こうした状況に理論的枠組みを与えるうえで,ダイグロシアは,正常で安定したものとして紹介される傾向にあり,それがみずから呈する言語紛争をもみ消して,状況が何も変わらないということをある意味で正当化する傾向にあった(実際,植民地支配を脱した国のほとんどにおいて起こったことであった).このような学問とイデオロギーとの関係は,稀なることではない.

・ Fishman, J. Sociolinguistics: A Brief Introduction. Rowley: Newbury House, 1971.

・ Fishman, J. "Prefatory Note." Languages in Contact and Conflict, XI. Ed. P. H. Nelde. Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1980.

・ Hudson, R. A. Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1996.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ(著),萩尾 生(訳) 『社会言語学』 白水社,2002年.

2013-05-22 Wed

■ #1486. diglossia を破った Chaucer [sociolinguistics][bilingualism][me][terminology][chaucer][reestablishment_of_english][diglossia]

「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」 ([2011-02-17-1]) で,初期中英語のイングランドにおける言語状況を diglossia として言及した.上層の書き言葉にラテン語やフランス語が,下層の話し言葉に英語が用いられるという,言語の使い分けが明確な言語状況である.3言語が関わっているので triglossia と呼ぶのが正確かもしれない.

diglossia という概念と用語を最初に導入したのは,社会言語学者 Ferguson である.Ferguson (336) による定義を引用しよう.

DIGLOSSIA is a relatively stable language situation in which, in addition to the primary dialects of the language (which may include a standard or regional standards), there is a very divergent, highly codified (often grammatically more complex) superposed variety, the vehicle of a large and respected body of written literature, either of an earlier period or in another speech community, which is learned largely by formal education and is used for most written and formal spoken purposes but is not used by any sector of the community for ordinary conversation.

定義にあるとおり,Ferguson は diglossia を1言語の2変種からなる上下関係と位置づけていた.例として,古典アラビア語と方言アラビア語,標準ドイツ語とスイス・ドイツ語,純粋ギリシア語と民衆ギリシア語 ([2013-04-20-1]の記事「#1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族)」を参照),フランス語とハイチ・クレオール語の4例を挙げた.

diglossia の概念は成功を収めた.後に,1言語の2変種からなる上下関係にとどまらず,異なる2言語からなる上下関係をも含む diglossia の拡大モデルが Fishman によって示されると,あわせて広く受け入れられるようになった.初期中英語のイングランドにおける diglossia は,この拡大版 diglossia の例ということになる.

さて,典型的な diglossia 状況においては,説教,講義,演説,メディア,文学において上位変種 (high variety) が用いられ,労働者や召使いへの指示出し,家庭での会話,民衆的なラジオ番組,風刺漫画,民俗文学において下位変種 (low variety) が用いられるとされる.もし話者がこの使い分けを守らず,ふさわしくない状況でふさわしくない変種を用いると,そこには違和感のみならず,場合によっては危険すら生じうる.中世イングランドにおいてこの危険をあえて冒した急先鋒が,Chaucer だった.下位変種である英語で,従来は上位変種の領分だった文学を書いたのである.Wardhaugh (86) は,Chaucer の diglossia 破りについて次のように述べている.

You do not use an H variety in circumstances calling for an L variety, e.g., for addressing a servant; nor do you usually use an L variety when an H is called for, e.g., for writing a 'serious' work of literature. You may indeed do the latter, but it may be a risky endeavor; it is the kind of thing that Chaucer did for the English of his day, and it requires a certain willingness, on the part of both the writer and others, to break away from a diglossic situation by extending the L variety into functions normally associated only with the H. For about three centuries after the Norman Conquest of 1066, English and Norman French coexisted in England in a diglossic situation with Norman French the H variety and English the L. However, gradually the L variety assumed more and more functions associated with the H so that by Chaucer's time it had become possible to use the L variety for a major literary work.

正確には Chaucer が独力で diglossia を破ったというよりは,Chaucer の時代までに,diglossia が破られうるまでに英語が市民権を回復しつつあったと理解するのが妥当だろう.

なお,diglossia に関しては,1960--90年にかけて3000件もの論文や著書が著わされたというから学界としては画期的な概念だったといえるだろう(カルヴェ,p. 31).

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

・ Ferguson, C. A. "Diglossia." Word 15 (1959): 325--40.

・ ルイ=ジャン・カルヴェ(著),西山 教行(訳) 『言語政策とは何か』 白水社,2000年.

2013-04-20 Sat

■ #1454. ギリシャ語派(印欧語族) [indo-european][family_tree][hellenic][greek][map][indo-european_sub-family][diglossia][koine]

「#1447. インド語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-13-1]) と「#1452. イラン語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-04-18-1]) に続き,印欧語族の語派を紹介するシリーズの第3弾.今回は Baugh and Cable (26--27) を参照して,ギリシャ語派(Hellenic)を紹介する.

ギリシャ語派は,たいていの印欧語系統図では語派レベルの Hellenic 以下に Greek とあるのみで,より細かくは分岐していないことから,比較的孤立した語派であるといえる.歴史時代の曙より,エーゲ海地方は人種と言語のるつぼだった.レムノス島,キプロス島,クレタ島,ギリシャ本土,小アジアからは,印欧語族の碑文や非印欧語族の碑文が混在して見つかっており,複雑な多民族,多言語社会を形作っていたようだ.

紀元前2000年を過ぎた辺りから,このるつぼの中へ,ギリシャ語派の言語の担い手が北から侵入した.この侵入は何度かの波によって徐々に進み,各段階で異なる方言がもたらされたために,ギリシャ本土,エーゲ海の島々,小アジアの沿岸などで諸方言が細かく分布する結果となった.最古の文学上の傑作は,盲目詩人 Homer による紀元前8世紀頃と推定される Illiad と Odyssey である.ギリシャ語には5つの主要方言群が区別される.(1) Ionic 方言は,重要な下位方言である Attic を含むほか,小アジアやエーゲ海の島々に分布した.(2) Aeolic 方言は,北部と北東部に分布,(3) Arcadian-Cyprian 方言は,ペロポネソスとキプロス島に分布した.(4) Doric 方言は,後にペロポネソスの Arcadian を置き換えた.(5) Northwest 方言は,北中部と北西部に分布した.

このうちとりわけ重要なのは Attic 方言である.Attic はアテネの方言として栄え,建築,彫刻,科学,哲学,文学の言語として Pericles (495--29 B.C.) に用いられたほか,Æschulus, Euripides, Sophocles といった悲劇作家,喜劇作家 Aristophanes,歴史家 Herodotus, Thucydides, 雄弁家 Demosthenes,哲学者 Plato, Aristotle によっても用いられた.この威信ある Attic は,4世紀以降,ギリシャ語諸方言の上に君臨する koiné として隆盛を極め,Alexander 大王 (336--23 B.C.) の征服により同方言は小アジア,シリア,メソポタミア,エジプトにおいても国際共通語として根付いた(koiné については,[2013-02-16-1]の記事「#1391. lingua franca (4)」を参照).新約聖書の言語として,また東ローマ帝国のビザンチン文学の言語としても重要である.

現代のギリシャ語諸方言は,上記 koiné の方言化したものである.現在,ギリシャ語は,自然発達した通俗体 (demotic or Romaic) と古代ギリシャ語に範を取った文語体 (Katharevusa) のどちらを公用とするかを巡る社会言語学的な問題を抱えている.

古代ギリシャ語は,英語にも直接,間接に多くの借用語を提供してきた言語であり,現在でも neo-classical compounds (とりわけ科学の分野)や接頭辞,接尾辞を供給し続けている重要な言語である.greek の各記事を参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2012-08-12 Sun

■ #1203. 中世イングランドにおける英仏語の使い分けの社会化 [french][me][norman_conquest][bilingualism][sociolinguistics][diglossia]

ノルマン・コンクェスト以後,イングランドにおける言語状況が英仏語の2言語使用 (bilingualism) となったことは,英語史において主要な話題である(今回はラテン語使用については触れない).だが,英語のみの単一言語使用 (monolingualism) だったところに,突如としてフランス語使用の慣習が入り込んだということはどういうことだろうか.多言語使用という状況にあまり馴染みのない者にとっては,想像するのは難しいかもしれない.英語史の授業でこの辺りの話題を出すと,さぞかし社会が混乱したのではないかという反応が聞かれる.何しろ海峡の向こうから異民族が異言語を引き下げて統治しにくるのだから,大事件のように思われるのも当然だ.

私自身,2言語使用に関する想像力が乏しいので,当時のイングランドの言語事情を具体的に思い浮かべるのに困難を感じる.しかし,民族との関わりよりも,社会階級の関わりにおいて言語をとらえると,中世イングランドにおける英仏語の関係をよりよく理解できるように思われる.

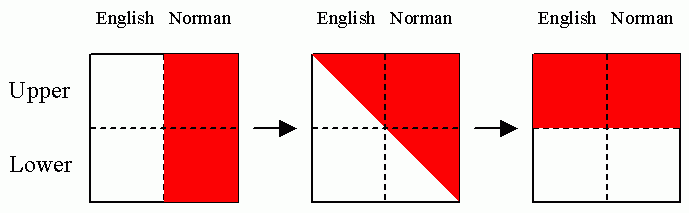

ノルマン・コンクェストの時点とその直後の時代には,「征服者たるノルマン人=フランス語」 vs 「被征服者たるイングランド人=英語」という対立の構図があったことは間違いない.ここでは,民族と言語が分かちがたく結びついている.しかし,征服から数世代を経て両民族の混血や交流が進むにつれ,英仏言語使用を区別する軸が,民族や出身地という軸から,社会階層という軸へと移ってきた.12世紀を通じて,イングランドの言語状況は,徐々に「上流階級=フランス語」 vs 「下流階級=英語」という対立の構図へと移行していったのである.移行の様子を(極度に)単純化して図示すれば,次のようになるだろう(赤がフランス語使用を表わす).

混血や交流が生じたとはいえ,12世紀でも「ノルマン系=上流階級」「イングランド系=下流階級」という図式がおよそ当てはまるのは事実である.しかし,英仏語の使い分けの軸が,民族や出身地を示す「系」から,階層としての「上下」に移った,あるいは「社会化」したと考えると,理解しやすい.この点について,Baugh and Cable (114--15) を引用しよう.

For 200 years after the Norman Conquest, French remained the language of ordinary intercourse among the upper classes in England. At first those who spoke French were those of Norman origin, but soon through intermarriage and association with the ruling class numerous people of English extraction must have found it to their advantage to learn the new language, and before long the distinction between those who spoke French and those who spoke English was not ethnic but largely social. The language of the masses remained English, and it is reasonable to assume that a French soldier settled on a manor with a few hundred English peasants would soon learn the language of the people among whom his lot was cast.

Baugh and Cable は外面史に定評のある英語史だが,とりわけノルマン・コンクェスト以後の中英語の社会言語学的状況に関して,記述に力が入っている.

関連して,[2011-02-17-1]の記事「#661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉」も参照.

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 5th ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

2011-02-17 Thu

■ #661. 12世紀後期イングランド人の話し言葉と書き言葉 [anglo-norman][writing][bilingualism][reestablishment_of_english][diglossia]

ノルマン征服によりイングランドの公用語が Old English から Norman French に切り替わった.イングランド内で後者は Anglo-French として発達し,Latin とともにイングランドの主要な書き言葉となった.ノルマン征服後の2世紀ほど,英語は書き言葉として皆無というわけではなかったが,ほとんどが古英語の伝統を引きずった文献の写しであり,当時の生きた中英語が文字として表わされていたわけではない.中英語の話し言葉を映し出す書き言葉としての中英語が本格的に現われてくるには,12世紀後半を待たなければならなかった.それまでは,イングランドの第1の書き言葉といえば英語ではなく,Anglo-French や Latin だったのである.

一方,ノルマン征服後のイングランドの話し言葉といえば,変わらず英語だった.フランス人である王侯貴族やその関係者は征服後しばらくはフランス語を母語として保持していたと考えられるし,イングランド人でも上流階級と接する機会のある人々は少なからずフランス語を第2言語として習得していただろう.しかし,イングランドの第1の話し言葉といえば英語に違いなかった ( see [2010-11-25-1] ) .

このように,ノルマン征服後しばらくの間は,イングランドにおける主要な話し言葉と書き言葉とは食い違っていた.12世紀後期において,イングランド人の書き手は普段は英語を話していながら,書くときには Anglo-French を用いるという切り替え術を身につけていたことになる.逆に言えば,12世紀後期までには,Anglo-French の書き手であっても主要な話し言葉は英語だった公算が大きい.Lass and Laing (3) を引用する.

By the early Middle English period, four generations after the Conquest, the high prestige languages in the written/spoken diglossia (though distantly cognate) were 'foreign': normally second and third languages, formally taught and learned. By the late 12th century it is virtually certain --- except in the case of scribes from continuingly bilingual families (and we do not have the information that would allow us to identify them) --- that none of the English scribes writing French were native speakers of French (though some may of course have been coordinate bilinguals). It is certain that none were native speakers of Latin, since after the genesis of the Romance vernaculars in the early centuries of this era it is most unlikely that there were any.

当時のイングランドの状況を日本の架空の状況に喩えてみれば,普段は日本語で話していながら,書くときには漢文を用いる(ただし中国語での会話は必ずしも得意ではないかもしれない)というような状況だろう.

12世紀後期イングランドにおける話し言葉と書き言葉の diglossia 「2言語変種使い分け」あるいは bilingualism については,Lass and Laing (p.3, fn. 3) に多くの参考文献が挙げられている.

・ Lass, Roger and Margaret Laing. "Interpreting Middle English." Chapter 2 of "A Linguistic Atlas of Early Middle English: Introduction.'' Available online at http://www.lel.ed.ac.uk/ihd/laeme1/pdf/Introchap2.pdf .

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow