2024-02-09 Fri

■ #5401. 文法上の性について60分間の対談精読実況生中継をお届けしました [bchel][gender][oe][noun][category][voicy][heldio][notice][hel_education]

去る2月6日(火)午後4時半より Voicy heldio にて「#983. B&Cの第42節「文法性」の対談精読実況生中継 with 金田拓さんと小河舜さん」を生放送でお届けしました.Baugh and Cable による英語史の古典的名著 A History of the English Language (第6版)を原書で精読するシリーズの一環です.今回は特別ゲストとして金田拓さん(帝京科学大学)と小河舜さん(フェリス女学院大学ほか)をお招きして,対談精読実況生中継としてお届けしました.上記は,昨日の通常配信でアーカイヴとして公開したものです.60分間の長丁場ですが,ぜひお時間のあるときにお聴きください.

2月5日(月)には,この hellog 上でも予告編となる記事「#5397. 文法上の「性」を考える --- Baugh and Cable の英語史より」 ([2024-02-05-1]) を公開しました.そちらの記事では今回注目した第42節 "Grammatical Gender" の原文を掲載していますので,それを眺めながらお聴きいただければと思います.そこからは,英語史における性 (gender) の話題に注目した重要な記事へのリンクも張っています.

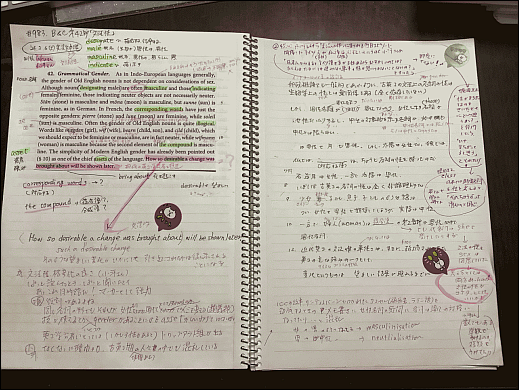

早々に配信を聴いてくださったコアリスナーの umisio さんが,まとめノートを作ってこちらのページで公開されています.ぜひ予習・復習のおともにご参照ください.

heldio で B&C の英語史を精読するシリーズのバックナンバー一覧は「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) でまとめています.全264節ある本の第42節にようやくたどり着いたところですので,まだまだ序盤戦です.皆さんには後追いでかまいませんので,このオンライン精読シリーズにご参加いただければ.まずは以下のテキストを入手してください!

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2024-02-05 Mon

■ #5397. 文法上の「性」を考える --- Baugh and Cable の英語史より [bchel][gender][oe][noun][category][voicy][heldio][notice][hel_education][link]

昨年7月より週1,2回のペースで Baugh and Cable の英語史の古典的名著 A History of the English Language (第6版)を原書で精読する Voicy 「英語の語源が身につくラジオ」 (heldio) でのシリーズ企画を進めています.1回200円の有料配信となっていますが第1チャプターに関してはいつでも試聴可です.またときどきテキストも公開しながら無料の一般配信も行なっています.これまでのバックナンバーは「#5291. heldio の「英語史の古典的名著 Baugh and Cable を読む」シリーズが順調に進んでいます」 ([2023-10-22-1]) にまとめてありますので,ご確認ください.

今までに41節をカバーしてきました.目下,古英語を扱う第3章に入っています.次回取り上げる第42節 "Grammatical Gender" は,古英語の名詞に確認される文法上の「性」,すなわち文法性 (gender) に着目します.以下に同節のテキストを掲載しておきます(できれば本書を入手していただくのがベストです).

42. Grammatical Gender. As in Indo-European languages generally, the gender of Old English nouns is not dependent on considerations of sex. Although nouns designating males are often masculine, and those indicating females feminine, those indicating neuter objects are not necessarily neuter. Stān (stone) is masculine, and mōna (moon) is masculine, but sunne (sun) is feminine, as in German. In French, the corresponding words have just the opposite genders: pierre (stone) and lune (moon) are feminine, while soleil (sun) is masculine. Often the gender of Old English nouns is quite illogical. Words like mægden (girl), wīf (wife), bearn (child, son), and cild (child), which we should expect to be feminine or masculine, are in fact neuter, while wīfmann (woman) is masculine because the second element of the compound is masculine. The simplicity of Modern English gender has already been pointed out as one of the chief assets of the language. How so desirable a change was brought about will be shown later.

文法性に関する話題は hellog でも gender のタグを付した多くの記事で取り上げてきました.そのなかから特に重要な記事へのリンクを以下に張っておきます.

・ 「#25. 古英語の名詞屈折(1)」 ([2009-05-23-1])

・ 「#26. 古英語の名詞屈折(2)」 ([2009-05-24-1])

・ 「#28. 古英語に自然性はなかったか?」 ([2009-05-26-1])

・ 「#487. 主な印欧諸語の文法性」 ([2010-08-27-1])

・ 「#1135. 印欧祖語の文法性の起源」 ([2012-06-05-1])

・ 「#2853. 言語における性と人間の分類フェチ」 ([2017-02-17-1])

・ 「#3293. 古英語の名詞の性の例」 ([2018-05-03-1])

・ 「#4039. 言語における性とはフェチである」 ([2020-05-18-1])

・ 「#4040. 「言語に反映されている人間の分類フェチ」の記事セット」 ([2020-05-19-1])

・ 「#4182. 「言語と性」のテーマの広さ」 ([2020-10-08-1])

・ Baugh, Albert C. and Thomas Cable. A History of the English Language. 6th ed. London: Routledge, 2013.

2023-03-20 Mon

■ #5075. 談話標識の言語的特徴 [discourse_marker][pragmatics][prototype][category]

昨日の記事「#5074. 英語の談話標識,43種」 ([2023-03-19-1]) で紹介した松尾ほか編著の『英語談話標識用法辞典』の補遺では,談話標識 (discourse_marker) についての充実した解説が与えられている.特に「談話標識についての基本的な考え方」の記事は有用である.

談話標識は品詞よりも一段高いレベルのカテゴリーであり,かつそのカテゴリーはプロトタイプ (prototype) として解釈されるべきものである,という説明から始まる.談話標識そのものがあるというよりも,談話標識的な用法がある,という捉え方に近い.その後に「談話標識の一般的特徴」と題するコラムが続く (333--34) .とてもよくまとまっているので,ここに引用しておきたい.

談話標識に共通する最も一般的な特徴は,「話し手の何らかの発話意図を合図する談話機能を備えている」ことである.ただし,「談話」 (discourse) は広義にとらえて,談話標識が現れる前後の文脈や,テクストとして具現化される文脈のみならず発話状況 (utterance situation) 全体を含むものとする.さらに,その発話状況に参与する話し手・聞き手の知識やコミュニケーションの諸要素が談話標識の機能に関与する.以下,いくつかの観点から談話標識の特徴をまとめる.

【語彙的・音韻的特徴】

(a) 一語からなるものが多いが,句レベル,節レベルのものも含まれる.

(b) 伝統的な単一の語類には集約できない.

(c) ポーズを伴い,独立した音調群を形成することが多い.

(d) 談話機能に応じ,さまざまな音調を伴う.

【統語的特徴】

(a) 文頭に現れることが多いが,文中,文尾に生じるものもある.

(b) 命題の構成要素の外側に生じる,あるいは統語構造にゆるやかに付加されて生じる.

(c) 選択的である.

(d) 複数の談話標識が共起することがある.

(e) 単独で用いられることがある.

【意味的特徴】

(a) それ自体で,文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味をほとんど,あるいは全く持たないものが多い.

(b) 文の真偽値に関わる概念的意味を持つ場合にも,文字通りの意味を表さ場合が多い.

【機能的特徴】

多機能的で,いくつかの談話レベルで機能するものが多い.

【社会的・文体的特徴】

(a) 書き言葉より話し言葉で用いられる場合が多い.

(b) くだけた文体で用いられるものが多い.

(c) 地域的要因,性別,年齢,社会階層,場面などによる特徴がある.

様々な角度から分析することのできる奥の深いカテゴリーであることが分かるだろう.昨日の記事 ([2023-03-19-1]) の43種の談話標識を思い浮かべながら,これらの特徴を確認されたい.

・ 松尾 文子・廣瀬 浩三・西川 眞由美(編著) 『英語談話標識用法辞典 43の基本ディスコース・マーカー』 研究社,2015年.

2022-12-17 Sat

■ #4982. 名詞と代名詞は異なる品詞か否か? [pos][noun][pronoun][category][sobokunagimon][prototype]

名詞 (noun) と代名詞 (pronoun) は2つの異なる品詞とみなすべきか,あるいは後者は前者の一部ととらえるべきか.品詞分類はなかなか厳密にはいかないのが常であり,見方によってはいずれも「正しい」という結論になることが多い.昨今は明確に白黒をつけるというよりは,プロトタイプ (prototype) としてファジーに捉えておくのがよい,という見解が多くなっているのかもしれない.しかし,最終的にはケリをつけないと気持ちが悪いと思うのも人間の性であり,やっかいなテーマだ.

Aarts が両陣営の議論をまとめているので引用する.

[ 名詞と代名詞は異なるカテゴリーとみなすべきである (Aarts, p. 25) ]

・ Pronouns show nominative and accusative case distinctions (she/her, we/us, etc.); common nouns do not.

・ Pronouns show person and gender distinctions; common nouns do not.

・ Pronouns do not have regular inflectional plurals in Standard English.

・ Pronouns are more constrained than common nouns in taking dependents.

・ Noun phrases with common or proper nouns as head can have independent reference, i.e. they can uniquely pick out an individual or entity in the discourse context, whereas the reference of pronouns must be established contextually.

[ 名詞と代名詞は同一のカテゴリーとみなすべきである (Aarts, p. 26) ]

・ Although common nouns indeed do not have nominative and accusative case inflections they do have genitive inflections, as in the doctor's garden, the mayor's expenses, etc., so having case inflections is not a property that is exclusive to pronouns.

・ Indisputably, only pronouns show person and arguably also gender distinctions, but this is not a sufficient reason to assign them to a different word class. After all, among the verbs in English we distinguish between transitive and intransitive verbs, but we would not want to establish two distinct word classes of 'transitive verbs' and 'intransitive verbs'. Instead, it would make more sense to have two subcategories of one and the same word class. If we follow this reasoning we would say that pronouns form a subcategory of nouns that show person and gender distinctions.

・ It's not entirely true that pronouns do not have regular inflectional plurals in Standard English, because the pronoun one can be pluralized, as in Which ones did you buy? Another consideration here is that there are regional varieties of English that pluralize pronouns (for example, Tyneside English has youse as the plural of you, which is used to address more than one person . . . . And we also have I vs. we, mine vs. ours, etc.

・ Pronouns do seem to be more constrained in taking dependents. We cannot say e.g. *The she left early or *Crazy they/them jumped off the wall. However, dependents are not excluded altogether. We can say, for example, I'm not the me that I used to be. or Stupid me; I forgot to take a coat. As for PP dependents: some pronouns can be followed by prepositional phrases in the same way as nouns can. Compare: The shop on the corner and one of the students.

・ Although it's true that noun phrases headed by common or proper nouns can have independent reference, while pronouns cannot, this is a semantic difference between nouns and pronouns, not a grammatical one.

この討論を経た後,さて,皆さんは異なるカテゴリー派,あるいは同一カテゴリー派のいずれでしょうか?

・ Aarts, Bas. "Syntactic Argumentation." Chapter 2 of The Oxford Handbook of English Grammar. Ed. Bas Aarts, Jill Bowie and Gergana Popova. Oxford: OUP, 2020. 21--39.

2022-10-25 Tue

■ #4929. mood と modality [mood][modality][category][terminology][subjunctive][auxiliary_verb][inflection]

標題の術語 mood と modality はよく混同される.『新英和大辞典』によると mood は「(動詞の)法,叙法《その表す動作状態に対する話者の心的態度を示す動詞の語形変化》」,modality は「法性,法範疇《願望・命令・謙遜など種々の心的態度を一定の統語構造によって表現すること」とある.両者の区別について,Bybee (165--66) が "Mood and modality" と題する節で丁寧に解説しているので,それを引用しよう.

The working definition of mood used in the survey is that mood is a marker on the verb that signals how the speaker chooses to put the proposition into the discourse context. The main function of this definition is to distinguish mood from tense and aspect, and to group together the well-known moods, indicative, imperative, subjunctive and so on. It was intentionally formulated to be general enough to cover both markers of illocutionary force, such as imperative, and markers of the degree of commitment of the speaker to the truth of the proposition, such as dubitative. What all these markers of the mood category have in common is that they signal what the speaker is doing with the proposition, and they have the whole proposition in their scope. Included under this definition are epistemic modalities, i.e. those that signal the degree of commitment the speaker has to the truth of the proposition. These are usually said to range from certainty to probability to possibility.

Excluded, however, are the other "modalities", such as the deontic modalities of permission and obligation, because they describe certain conditions on the agent with regard to the main predication. Some of the English modal auxiliaries have both an epistemic and a deontic reading. The following two examples illustrate the deontic functions of obligation and permission respectively:

Sally must be more polite to her mother.

The students may use the library at any time.

The epistemic functions of these same auxiliaries can be seen by putting them in a sentence without an agentive subject:

It must be raining.

It may be raining.

Now the auxiliaries signal the speaker's degree of commitment to the proposition "it is raining". Along with deontic modalities, markers of ability, desire and intention are excluded from the definition of mood since they express conditions pertaining to the agent that are in effect with respect to the main predication. I will refer to obligation, permission, ability, desire and intention as "agent-oriented" modalities.

The hypothesis implicit in the working definition of mood as an inflectional category is that markers of modalities that designate conditions on the agent of the sentence will not often occur as inflections on verbs, while markers that designate the role the speaker wants the proposition to play in the discourse will often occur as inflections. This hypothesis was overwhelmingly supported by the languages in the sample. Hundreds of inflectional markers that fit the definition of mood were found to occur in the languages of the sample. In fact, such markers are the most common type of inflection on verbs. However, inflectional markers of obligation, permission, ability or intention are extremely rare in the sample, and occur only under specific conditions.

mood は主として形態論(および付随して意味論)的カテゴリーで命題志向,modality は主として意味論的カテゴリーで命題志向のこともあれば行為者志向のこともある,ととらえてよさそうだ.意味論の観点からいえば,前者は後者に包摂されることになる.Bybee (169) による要約は次の通り.

The cross-linguistic data suggest, then, the following uses of the terms modality and mood. Modality designates a conceptual domain which may take various types of linguistic expression, while mood designates the inflectional expression of a subdivision of this semantic domain. Since there is much cross-linguistic consistency concerning which modalities are expressed inflectionally, mood can refer both to the form of expression, and to a conceptual domain.

・ Bybee, Joan. Morphology: A Study of the Relation between Meaning and Form. John Benjamins, Amsterdam/Philadelphia, 1985.

2022-10-17 Mon

■ #4921. Murray の英文法の9品詞論 [pos][lowth][prescriptive_grammar][history_of_linguistics][category]

一昨日の記事「#4919. Lowth の英文法の9品詞論」 ([2022-10-15-1]) を受けて,今回は Lindley Murray (1745--1826) の品詞論について.Murray といえば,「#2592. Lindley Murray, English Grammar」 ([2016-06-01-1]) でも取り上げた通り,Lowth などを下敷きにしつつ,18世紀規範英文法を集大成した「英文法の父」である.

1795年に English Grammar, adapted to the different classes of learners; With an Appendix, containing Rules and Observations for Promoting Perspicuity in Speaking and Writing を出版するや爆発的な人気を誇り,その売り上げは1850年までに150万部以上を記録したという.斎藤 (42) によると,English Grammar は「日本最初の本格的な英文法書」となる渋川敬直による『英文鑑(えいぶんかがみ)』 (1840--41) の底本ともなった.

Murray の英文法は Lowth などを引き継ぎ,9品詞論が基本となっている.斎藤 (45) より区分を示そう.

(1) 冠詞 (Article): Definite/Indefinite

(2) 名詞 (Substantive or Noun): Common/Proper

数 (Number): Singular/Plural

格 (Case): Nominative/Possessive/Objective

性 (Gender): Masculine/Feminine/Neuter

(3) 形容詞 (Adjective)

比較 (Comparison): Positive/Comparative/Superlative

(4) 代名詞 (Pronoun): Personal※1/Relative※2/Adjective※3

※1 人称 (Person): First/Second/Third

※2 Interrogative は,Relative pronoun の一部

※3 Adjective: Possessive/Distributive/Demonstrative/Indefinite

(5) 動詞 (Verb): Active (Transitive)/Passive/Neuter (Intransitive)

法 (Mood or Mode):

Indicative/Imperative/Potential/Subjunctive/Infinitive

時制 (Tense):

Present/Past (Imperfect)/Perfect(現在完了のこと)/Pluperfect(過去完了のこと)/First future(単純未来形のこと)/Second future(未来完了のこと)

分詞 (Participle),助動詞 (Auxiliary or helping Verbs)

能動態・受動態 (Active voice/Passive voice)

規則・不規則・欠如動詞 (Regular/Irregular/Defective)

(6) 副詞 (Adverb):

Number/Order/Place/Time/Quantity/Manner or quality/Doubt/Affirmation/Negation/Interrogation/Comparison

(7) 前置詞 (Preposition)

(8) 接続詞 (Conjunction): Copulative/Disjunctive

(9) 間投詞 (interjection)

同じ9品詞論でも Lowth の区分との間に若干の差異がある.例えば名詞の格のカテゴリーについて,Murray は Lowth の Nominative/Possessive に加えて Objective も含めている.また,分詞について Lowth は法のカテゴリーに含めているが,Murray は動詞の1形式とみている.

全体として Murray の9品詞論は,現代的な英文法観にまた一歩近づいているということができるだろう.

・ 斎藤 浩一 『日本の「英文法」ができるまで』 研究社,2022年.

2022-10-15 Sat

■ #4919. Lowth の英文法の9品詞論 [pos][lowth][prescriptive_grammar][history_of_linguistics][category]

最も著名な18世紀の規範文法家 Robert Lowth (1710--87) とその著書 A Short Introduction to English Grammar (1762) について,hellog では「#2583. Robert Lowth, Short Introduction to English Grammar」 ([2016-05-23-1]) や lowth の各記事で取り上げてきた.昨日の記事「#4918. William Bullokar の8品詞論」 ([2022-10-14-1]) を受けて,Lowth の品詞論を確認しておこう.Lowth は9品詞を掲げている.以下,斎藤 (26--27) より.

(1) 冠詞 (Article): Definite/Indefinite

(2) 名詞 (Substantive, or Noun): Common/Proper

数 (Number): Singular/Plural

格 (Case): Nominative/Possessive

性 (Gender): Masculine/Feminine/Neuter

(3) 代名詞 (Pronoun):

Personal/Relative/Interrogative/Definitive/Distributive/Reciprocal

※ 人称 (Person): First/Second/Third

(4) 形容詞 (Adjective), (5) 副詞 (Adverb)

比較 (Comparison): Positive/Comparative/Superlative

(6) 動詞 (Verb): Active (Transitive)/Passive/Neuter (Intransitive)

法 (Mode): Indicative/Imperative/Subjunctive/Infinitive/Participle

時制 (Tense):

Present/Past/Future

Present Imperfect/Present Perfect/Past Imperfect

Past Perfect/Future Imperfect/Future Perfect

※ 'Imperfect' は,現代の「進行形」に相当

助動詞 (Auxiliary),規則・不規則動詞 (Regular/Irregular)

欠如動詞 (Defective)

(7) 前置詞 (Preposition)

(8) 接続詞 (Conjunction): Copulative/Disjunctive

(9) 間投詞 (interjection)

Bullokar の8品詞論と比べて Lowth の9品詞論について注目すべき点は,冠詞 (Article) が加えられていること,名詞から形容詞が分化し区別されるようになっていること,分詞が動詞の配下の1区分として格下げされていることである.斎藤 (27) も述べている通り「全体として見れば,現代のわれわれにとりなじみ深い概念の多くが成立していることも事実であり,これこそ16世紀以来続いた試行錯誤の一応の到達点だった」と理解することができる.

・ 斎藤 浩一 『日本の「英文法」ができるまで』 研究社,2022年.

2022-09-06 Tue

■ #4880. 「定動詞」「非定動詞」という用語はややこしい [category][verb][finiteness][article][terminology][agreement][tense][number][person][mood][adjective]

英語の動詞 (verb) に関するカテゴリーの1つに定性 (finiteness) というものがある.動詞の定形 (finite form) とは,I go to school. She goes to school. He went to school. のような動詞 go の「定まった」現われを指す.一方,動詞の非定形 (nonfinite form) とは,I'm going to school. Going to school is fun. She wants to go to school. He made me go to school. のような動詞 go の「定まっていない」現われを指す.

「定性」という用語がややこしい.例えば,(to) go という不定詞は変わることのない一定の形なのだから,こちらこそ「定」ではないかと思われるかもしれないが,名実ともに「不定」と言われるのだ.一方,goes や went は動詞 go が変化(へんげ)したものとして,いかにも「非定」らしくみえるが,むしろこれらこそが「定」なのである.

この分かりにくさは finiteness を「定性」と訳したところにある.finite の原義は「定的」というよりも「明確に限定された」であり,nonfinite は「非定的」というよりも「明確に限定されていない」である.例えば He ( ) to school yesterday. という文において括弧に go の適切な形を入れる場合,文法と意味の観点から went の形にするのがふさわしい.ふさわしいというよりは,文脈によってそれ以外の形は許されないという点で「明確に限定された」現われなのである.

別の考え方としては,動詞にはまず GO や GOING のような抽象的,イデア的な形があり,それが実際の文脈においては go, goes, went などの具体的な形として顕現するのだ,ととらえてもよい.端的にいえば finite は「具体的」で,infinite は「抽象的」ということだ.

言語学的にもう少し丁寧にいえば,動詞の定性とは,動詞が数・時制・人称・法に応じて1つの特定の形に絞り込まれているか否かという基準のことである.Crystal (224) の説明を引用しよう.

The forms of the verb . . . , and the phrases they are part of, are usually classified into two broad types, based on the kind of contrast in meaning they express. The notion of finiteness is the traditional way of classifying the differences. This term suggests that verbs can be 'limited' in some way, and this is in fact what happens when different kinds of endings are used.

・ The finite forms are those which limit the verb to a particular number, tense, person, or mood. For example, when the -s form is used, the verb is limited to the third person singular of the present tense, as in goes and runs. If there is a series of verbs in the verb phrase, the finite verb is always the first, as in I was being asked.

・ The nonfinite forms do not limit the verb in this way. For example, when the -ing form is used, the verb can be referring to any number, tense, person, or mood:

I'm leaving (first person, singular, present)

They're leaving (third person, plural, present)

He was leaving (third person, singular, past)

We might be leaving tomorrow (first person, plural, future, tentative)

As these examples show, a nonfinite form of the verb stays the same in a clause, regardless of the grammatical variation taking place alongside it.

なお,英語には冠詞にも定・不定という区別があるし,古英語には形容詞にも定・不定の区別があった.これらのカテゴリーに付けられたラベルは "finiteness" ではなく "definiteness" である.この界隈の用語は誤解を招きやすいので要注意である.

・ Crystal, D. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language. 3rd ed. CUP, 2018.

2022-07-22 Fri

■ #4834. 比較級・最上級の歴史 [comparison][category][adjective][adverb][youtube][notice][link][grammaticalisation]

一昨日,YouTube 「井上逸兵・堀田隆一英語学言語学チャンネル」の第42弾が公開されました.「英語の比較級・最上級はなぜ多様なのか?」と題して,英語の比較級・最上級の形式の歴史についてお話ししています.

英語を含む印欧諸語では日本語と異なり,形容詞や副詞に比較級 (comparative degree) や最上級 (superlative degree) といった「級」の文法カテゴリーがあります.比較・最上の概念が文法化 (grammaticalisation) されているのです.そのため英語では比較に関する語法や構文が様々に発達しています.

形式に注目しても,例えば比較級は -er 語尾を付けるもの,more を前置するもの,better や worse のように補充法 (suppletion) に訴えるものなど,種類が豊富です.

このように「級」については英語史・英語学的に論点が多いこともあり,hellog その他でもしばしば関連する話題に触れてきました.以下はこの問題に関心をもった方へのお薦め記事・放送です.より広く記事を読みたい方は comparison の記事群をどうぞ.

[ hellog 記事 ]

・ 「#3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について」 ([2019-10-27-1])

・ 「#3843. なぜ形容詞・副詞の「原級」が "positive degree" と呼ばれるのか?」 ([2019-11-04-1])

・ 「#3844. 比較級の4用法」 ([2019-11-05-1])

・ 「#4616. 形容詞の原級と比較級を巡る意味論」 ([2021-12-16-1])

・ 「#403. 流れに逆らっている比較級形成の歴史」 ([2010-06-04-1])

・ 「#2346. more, most を用いた句比較の発達」 ([2015-09-29-1])

・ 「#2347. 句比較の発達におけるフランス語,ラテン語の影響について」 ([2015-09-30-1])

・ 「#3032. 屈折比較と句比較の競合の略史」 ([2017-08-15-1])

・ 「#3349. 後期近代英語期における形容詞比較の屈折形 vs 迂言形の決定要因」 ([2018-06-28-1])

・ 「#3617. -er/-est か more/most か? --- 比較級・最上級の作り方」 ([2019-03-23-1])

・ 「#3618. Johnson による比較級・最上級の作り方の規則」 ([2019-03-24-1])

・ 「#4234. なぜ比較級には -er をつけるものと more をつけるものとがあるのですか? --- hellog ラジオ版」 ([2020-11-29-1])

・ 「#4442. 2音節の形容詞の比較級は -er か more か」 ([2021-06-25-1])

・ 「#4495. 『中高生の基礎英語 in English』の連載第6回「なぜ形容詞の比較級には -er と more があるの?」」 ([2021-08-17-1])

[ heldio & hellog-radio (← heldio の前身) ]

・ hellog-radio 「#46. なぜ比較級には -er をつけるものと more をつけるものとがあるのですか?」

・ heldio 「#97. unhappyの比較級に -er がつくのは反則?」

2022-02-07 Mon

■ #4669. he と she を区別しない世界英語の変種 [world_englishes][new_englishes][gender][category][variety][personal_pronoun][substratum_theory]

現代の世界英語 (world_englishes) の多様性を前提とすれば,標題のような特性をもつ英語変種があったとしても驚かないだろう.3人称単数代名詞の使用において形態的に男女の区別をつけない変種,つまり標準英語のように he と she (および it)の区別を明確につけない変種があるのである.

例えば,東アフリカ英語やマレーシア英語では,しばしば指示対象にかかわらず,いずれの3人称単数代名詞も用いられ得るという.Mesthrie and Bhatt (55--56) より,関係する箇所を引用する.

Gender has proved --- despite its minor role in English --- susceptible to variation in New Englishes. Some varieties use gender in pronouns differently. Platt, Weber and Ho . . . report that in some New Englishes where the background languages do not make a distinction between he, she and it, pronouns 'are often used indiscriminately'. They offer the following examples:

41. My husband who was in England, she was by then my fiancé. (East Africa)

42. My mother, he live in kampong. (Malaysia)

Since Bantu languages do not make sex-based distinction with pronouns, and the spoken forms of the Chinese languages of Singapore and Malaysia do not differentiate gender in 3rd person pronouns . . . , substrate influences may well be at work here.

標準英語のみを知っている者にとって,これは驚くべき現象のように思われるかもしれない.しかし,英語史を研究している者にとっては,まったく驚くべきことではない.中英語では,方言にもよるが,しばしば he という3人称単数の代名詞形態が男性をも女性をも指示し得るからである.さらにひどい(!)場合には,(性を問わない)複数人称代名詞も同じ he で表わされたりする.中英語の場合には,意味論的な性の区別の消失ではなく,あくまで形態的な合一という原因により区別がつかなくなったということであり,上記の東アフリカ英語やマレーシア英語のケースとは事情が異なるのだが,「現代の World Englishes は広し」と叫ぶ前に「歴史的な英語諸変種もまた広し」と叫んでおきたい.

・ Mesthrie, Rajend and Rakesh M. Bhatt. World Englishes: The Study of New Linguistic Varieties. Cambridge: CUP, 2008.

2022-01-24 Mon

■ #4655. 動詞の「相」って何ですか? [aspect][tense][category][sobokunagimon][verb][terminology][perfect][progressive]

多くの言語には,時間 (time) に関連する概念を標示する機能があります.まず,日本語にも英語にもあって分かりやすいのは時制 (tense) という範疇 (category) ですね.過去,現在,未来という時間軸上のポイントを示すアレです.

もう1つ,よく聞くのが相 (aspect) です.aspect という英単語は「局面,側面,様態,視座,相」ほどを意味し,いずれで訳してもよさそうですが,最も分かりにくい「相」が定訳となっているので困ります.難しそうなほうが学術用語としてありがたがられるという目論見だったのでしょうかね.あまり感心できませんが,定着してしまったものを無視するわけにもいきませんので,今回は「相」で通します.

さて,aspect や「相」について参考書を調べてみると,様々な定義や解説が挙げられていますが,互いに主旨は大きく異なりません.

動詞に関する文法範疇の一つで,動詞の表わす動作・状態の様相のとらえ方およびそれを示す文法形式をいう.(『新英語学辞典』, p. 96)

The grammatical category (expressed in verb forms) that refers to a way of looking at the time of a situation: for example, its duration, repetition, completion. Aspect contrasts with tense, the category that refers to the time of the situation with respect to some other time: for example, the moment of speaking or writing. There are two aspects in English: the progressive aspect ('We are eating lunch') and the perfect aspect ('We have eaten lunch'). (McArthur 86)

A grammatical category concerned with the relationship between the action, state or process denoted by a verb, and various temporal meanings, such as duration and level of completion. There are two aspects in English: the progressive and the perfect. (Pearce 18)

半年ほど前のことですが,オンライン授業の最中に,学生よりズバリ「相」って何ですかという質問がチャットで寄せられました.そのときに次の即席の回答をしたことを思い出しましたので,こちらに再現します.授業中ということもあり,その場での分かりやすさを重視し,カジュアルで私的な解説にはなっていますが,かえって分かりやすいかもしれません.

相が時制とどう違うか,という内容の問題でしょうかね? そうするとけっこう難しいのですが,よく言われるのは「相」は動詞の表わす動作の内部時間の問題,「時制」は動詞の表わす動作の外部時間の問題とか言われます.

例えば jump 「跳ぶ」の外部時間は分かりやすくて「跳んだ」「跳ぶ」「跳ぶだろう」ですね.内部時間というのは,「跳ぶ」と一言でいっても,脚の筋肉を緊張させて跳び始めようかなという段階(=相)もあれば,実際跳び始めてるよという段階(=相)もあるし,跳んでいて空中にいる最中の段階(=相)もあれば,跳び終わって着時寸前の段階(=相)もあれば,跳び終わっちゃった段階(=相)もあるというように,今の例では少なくとも5段階くらいあるわけです.スローモーションの画像のどこで止めようかという話しです.この細かい段階を表わすのが「相」です.時間が関わってくる点では共通していますが,「時制」とは別次元の時間の捉え方ですよね.

言語における「相」の概念の一部のみをつかんだ取り急ぎの解説にすぎませんが,参考になれば.

もう少し本格的には「#2747. Reichenbach の時制・相の理論」 ([2016-11-03-1]) も参照.

・ 大塚 高信,中島 文雄(監修) 『新英語学辞典』 研究社,1982年.

・ McArthur, Tom, ed. The Oxford Companion to the English Language. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

・ Pearce, Michael. The Routledge Dictionary of English Language Studies. Abingdon: Routledge, 2007.

2022-01-22 Sat

■ #4653. 可算名詞と不可算名詞の区別は近代英語期にかけて生じた [noun][countability][semantics][sobokunagimon][article][hc][category]

先日「#4649. 可算名詞と不可算名詞の区別はいつ生まれたのか?」 ([2022-01-18-1]) の記事を投稿したところ,読者の方より関連する論文がある,ということで教えていただきました.私の寡聞にして存じあげなかった Toyota 論文です.たいへんありがたいことです.早速読んでみました.

論文の主旨は非常に明快です.Toyota (118) の冒頭より,論文を要約している文章を引用します.

Our main question is about how the distinction between mass and count nouns evolved. Earlier English surprisingly has a relatively poor counting system, the distinction between count and mass nouns not being clear. This poor distinction in earlier English has developed into a new systems of considering certain referents as mass nouns, and these referents came to be counted differently from those considered as count nouns. There are various changes involved in this development, and it is possible that factors like language contact caused the change. This view is challenged, asking whether other possibilities, such as a change in human cognition and the world-view of speakers, also affected this development.

同論文によれば,古英語から初期中英語までは,可算性 (countability) に関する区別は明確にはなかったということです(その種のようなものはあったのですが).これは,可算性の区別をつけていなかったと考えられる印欧祖語の特徴の継承・残存と考えてよさそうです.

ところが,後期中英語から,とりわけ初期近代英語期にかけて,突如として現代に通じる可算性の区別がつけられるようになってきました.背景には,すでに可算性の区別を獲得していたラテン語やフランス語からの影響が考えられますが,それだけでは比較的短い期間内に明確な区別が生じた事実を十分には説明できません.そこで,言語接触により触発された可能性は認めつつも,内発的に英語における「世界観」(弱めにいえば「名詞の分節基準」ほどでしょうか)が変化したのではないか,と Toyota は提言しています.

Helsinki Corpus による経験的な調査として注目に値します.仮説として立てられた「世界観」の変化を実証するにはクリアしなければならない問題がまだ多くあるように思いましたが,それでも,たいへん理解しやすい野心的な試みとして読むことができました.私も,俄然この問題に関心が湧いてきました.

・ Toyota, Junichi. "When the Mass Was Counted: English as Classifier and Non-Classifier Language." SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 6.1 (2009): 118--30. Available online at http://www.skase.sk/Volumes/JTL13/pdf_doc/07.pdf .

2022-01-18 Tue

■ #4649. 可算名詞と不可算名詞の区別はいつ生まれたのか? [noun][countability][semantics][sobokunagimon][article][category]

名詞の可算性 (countability) は現代英語における重要な問題だが,本ブログでまともに扱ったことがなかったことに気づいた.「#4335. 名詞の下位分類」 ([2021-03-10-1]),「#4214. 強意複数 (1)」 ([2020-11-09-1]),「#4215. 強意複数 (2)」 ([2020-11-10-1]),「#2808. Jackendoff の概念意味論」 ([2017-01-03-1]) 辺りで間接的に触れてきた程度である.私自身,この問題について歴史的に向き合ったことがなかったということもある.

日本語母語話者として英語を学んできて,なぜこの単語は不可算名詞なのか,と疑問を抱いたことは一度や二度ではない.次に挙げる単語は,そのまま数えられそうでいて英語では数えられということになっており,強引に数えたい場合にはいちいち単位を表わす可算名詞を用いた表現にパラフレーズしなければならない.例えば Quirk et al. (§5.9)によると次の通り.

| NONCOUNT NOUN | COUNT EQUIVALENT |

| This is important information | a piece/bit/word of information |

| Have you any news? | a piece/a bit/an item of good news |

| a lot of abuse | a term/word of abuse |

| some good advice | a piece/word of good advice |

| warm applause | a round of applause |

| How's business? | a piece/bit of business |

| There is evidence that . . . | a piece of evidence |

| expensive furniture | a piece/an article/a suite of furniture |

| The interest is only 5 percent. | a (low) rate of interest |

| What (bad/good) luck! | a piece of (bad/good) luck |

英語史の観点からの興味は,可算名詞と不可算名詞の区別がいつ頃生まれたのかということである.意味論的には,名詞の可算性の区別そのものは古英語期にもあったのだろうか.あくまで形式的にいえば,名詞の可算性が顕在化するのは,主として不定冠詞の用法が発達してからのことだろう.不定冠詞が厳密にいつ確立したかは議論のあるところだが,「#2144. 冠詞の発達と機能範疇の創発」 ([2015-03-11-1]) で見たように中英語期以降であることは認めてよいだろう.それ以降は,不定冠詞が付くことができれば可算名詞であり,付くことができなければ不可算名詞であると判定し得るので,調査のしようがあるように思われる.では,上記の単語はその当初から不可算名詞だったのだろうか.そして,単位(可算)名詞を伴う表現もその当初からあったのだろうか.あるいは,可算・不可算の区別自体が,それ以降,徐々に発達してきたものなのだろうか.

名詞の可算性の顕在化は,主に付随する不定冠詞の有無によって判定し得ると述べたが,それ以外の形式的な判定基準もあるかもしれない.例えば「#2697. few と a few の意味の差」 ([2016-09-14-1]),「#3051. 「less + 複数名詞」はダメ?」 ([2017-09-03-1]),「#3052. そのような用法は昔からあった,だから何?」 ([2017-09-04-1]),「#2035. 可算名詞は he,不可算名詞は it で受けるイングランド南西方言」 ([2014-11-22-1]) で取り上げたような議論も関連してくるのではないか.

本格的に調べたことがないので,現時点で私に言えることはないが,少しずつ追いかけてみようと思う.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

2021-09-29 Wed

■ #4538. 固有名の地位 [onomastics][toponymy][personal_name][semantics][noun][category][linguistics][semiotics][sign]

あまりにおもしろそうで,手を出してしまったら身を滅ぼすことになるかもしれないという分野がありますね.私にとって,それは固有名詞学 (onomastics) です.端的にいえば人名や地名の話題です.泥沼にはまり込むことが必至なので必死で避けているのですが,数年に一度,必ずゼミ生がテーマに選ぶのです.たいへん困ります.困ってしまうほど,私にとって磁力が強いのです.

固有名詞の問題,要するに「名前」の問題ほど,言語学において周辺的な素振りをしていながら,実は本質的な問題はありません.言葉は名前に始まり名前に終わる可能性があるからです (cf. 「#1184. 固有名詞化 (1)」 ([2012-07-24-1]),「#1185. 固有名詞化 (2)」 ([2012-07-25-1]) で触れた "Onymic Reference Default Principle" (ORDP)).

そもそも固有名詞というのは,言語の一部なのかそうでないのか,というところからして問題になるのが悩ましいですね.タモリさんではありませんが,私が「パリ,リヨン,マルセーユ,ブルゴーニュ」と上手なフランス語の発音で言えたとしても,フランス語がよく話せるということになりません.そもそも地名はフランス語なのかどうなのかという問題があるからです (cf. 「#2979. Chibanian はラテン語?」 ([2017-06-23-1])).

英語史のハンドブックに,Coates による固有名詞学に関する章がありました.その冒頭の「固有名の地位」と題する1節より,最初の段落を引用します (312) .

The status of proper names

Names is a technical term for a subset of the nominal expressions of a language which are used for referring ('identifying or selecting in context') and, in some cases, for addressing a partner in communication. Nominal expressions are in general headed by nouns. According to one of the most ancient distinctions in linguistics, nouns may be common or proper, which has something to do with whether they denote a class or an individual (e.g. queen vs Victoria), where individual means a single-member set of any sort, not just a person. Much discussion has taken place about how this distinction should be refined to be both accurate and useful, for instance by addressing the obvious difficulty that a typical proper noun denoting persons may denote many separate individuals who bear it, and that common nouns may refer to individuals by being constructed into phrases (the queen). I will leave the concept [賊proper], applied to nouns, for intuitive or educated recognition before returning to discussion of the inclusive concept of proper names directly. Proper nouns have no inherent semantic content, even when they are homonymous with lexical words (Daisy, Wells), and many, perhaps all, cultures recognise nouns whose sole function is to be proper (Sarah, Ipswich). Typically they have a unique intended referent in a context of utterance. Proper names are the class of such proper nouns included in the class of all expressions which have the properties of being devoid of sense and being used with the intention of achieving unique reference in context. Onomastics is the study of proper names, and concentrates on proper nouns; I shall confine the main subject-matter of this chapter to the institutionalised proper nouns associated with English and, in accordance with ordinary usage, I shall call them proper names or just names. Readers should note that strictly speaking these are a subset of proper names, and from time to time other members of the larger set will be discussed. There is some evidence from aphasiology and cognitive neuropsychology that institutionalised proper nouns --- especially personal names --- form a psychologically real class . . . .

これだけでおもしろそうと感じた方は,仲間かもしれません.ぜひ章全体を読んでみてください.

・ Coates, Richard. "Names." Chapter 6 of A History of the English Language. Ed. Richard Hogg and David Denison. Cambridge: CUP, 2006. 312--51.

2021-09-14 Tue

■ #4523. 時制 --- 屈折語尾の衰退をくぐりぬけて生き残った動詞のカテゴリー [inflection][conjugation][ilame][verb][noun][category][tense][mood][person]

古英語期(以前)に始まり中英語期をかけてほぼ完遂した屈折語尾の衰退は,英語形態論における史上最大の出来事だったといってよい.これにより英語の言語としての類型がひっくり返ってしまったといっても過言ではない.とりわけ名詞,動詞,形容詞の形態論は大規模な再編成を余儀なくされ,各品詞と結びついていた文法カテゴリー (category) も大幅に組み替えられることになった.

名詞についていえば,古英語では性 (gender),数 (number),格 (case) の3カテゴリーの三位一体というべき形態論が機能していたが,中英語ではおよそ性と格のカテゴリーが弱化・消失にさらされ,数が優勢となって今に至る.

動詞については,古英語では人称 (person),数 (number),法 (mood),時制 (tense) が機能的だったが,屈折語尾の衰退の荒波に洗われ,時制以外のカテゴリーの効き具合が弱まった.一応すべてのカテゴリーが現代まで生き延びているとはいえ,結果的に優位を獲得したのは時制である.

Lass (161) は,近現代英語の動詞のカテゴリーを形態的な区別という観点から整理し,次のように図式化した.

TENSE ─┬─ pres. ── MOOD ─┬─ ind. ── NUM. ─┬─ sing. ── PERS. ─┬┬─ 1, 2 -0

│ │ │ ││

│ │ │ └── 3 ── -s

│ │ │ │

│ │ └─ pl. ─────┬──┘

│ │ │

│ └── subj./imp. ─────────────┘

│

│

└─ past ────────────────────────────────────── -d

動詞の定形を決定する最重要カテゴリーとして時制が君臨し,過去形においては法すらも区別されない形態論となっている.Lass (159--61) に古英語,後期中英語,初期近代英語の対応する樹形図もある.比較すると形態論の再編成がよく分かる.

・ Lass, Roger. "Phonology and Morphology." 1476--1776. Vol. 3 of The Cambridge History of the English Language. Ed. Roger Lass. Cambridge: CUP, 1999. 56--186.

2021-06-19 Sat

■ #4436. 形容詞のプロトタイプ [comparison][adjective][adverb][category][prototype][pos][comparison]

品詞 (part of speech = pos) というものは,最もよく知られている文法範疇 (category) の1つである.たいていの言語学用語なり英文法用語なりは,文法範疇につけられたラベルである.主語,時制,数,格,比較,(不)可算,否定などの用語が出てきたら,文法範疇について語っているのだと考えてよい.

英語の形容詞(および副詞)という品詞について考える場合,比較 (comparison) という文法範疇が話題の1つとなる.日本語などでは「比較」を文法範疇として特別扱いする慣習はなく,せいぜい格助詞「より」の用法の1つとして論じられる程度だが,印欧語族においては言語体系に深く埋め込まれた文法範疇として,特別視されることになっている.私はいまだにこの感覚がつかめていないのだが,英語学において比較という文法範疇が通時的にも共時的にも重要視されてきたことは確かである.

比較はまずもって形容詞(および副詞)の文法範疇ということだが,ある語が形容詞であるからといって,必ずしもこの範疇が関与するわけではない.本当に形容詞らしい形容詞は比較の範疇に適合するが,さほど形容詞らしくない形容詞は比較とは相容れない.逆に見れば,ある形容詞を取り上げたとき,比較の範疇に適合するかどうかで,形容詞らしい形容詞か,そうでもない形容詞かが判明する.これは,とりもなおさず形容詞に関するプロトタイプ (prototype) の問題である.

Crystal (92) が,形容詞のプロトタイプについて分かりやすい説明を与えてくれている.

The movement from a central core of stable grammatical behaviour to a more irregular periphery has been called gradience. Adjectives display this phenomenon very clearly. Five main criteria are usually used to identify the central class of English adjectives:

(A) they occur after forms of to be, e.g. he's sad;

(B) they occur after articles and before nouns, e.g. the big car;

(C) they occur after very, e.g. very nice;

(D) they occur in the comparative or superlative form e.g. sadder/saddest, more/most impressive; and

(E) they occur before -ly to form adverbs, e.g. quickly.

We can now use these criteria to test how much like an adjective a word is. In the matrix below, candidate words are listed on the left, and the five criteria are along the top. If a word meets a criterion, it is given a +; sad, for example, is clearly an adjective (he's sad, the sad girl, very sad, sadder/saddest, sadly). If a word fails the criterion, it is given a - (as in the case of want, which is nothing like an adjective: *he's want, *the want girl, *very want, *wanter/wantest, *wantly).

A B C D E happy + + + + + old + + + + - top + + + - - two + + - - - asleep + - - - - want - - - - -

The pattern in the diagram is of course wholly artificial because it depends on the way in which the criteria are placed in sequence; but it does help to show the gradual nature of the changes as one moves away from the central class, represented by happy. Some adjectives, it seems, are more adjective-like than others.

形容詞という文法範疇について,特にその比較という文法範疇については,以下の記事を参照.

・ 「#3533. 名詞 -- 形容詞 -- 動詞の連続性と範疇化」 ([2018-12-29-1])

・ 「#3835. 形容詞などの「比較」や「級」という範疇について」 ([2019-10-27-1])

・ 「#3843. なぜ形容詞・副詞の「原級」が "positive degree" と呼ばれるのか?」 ([2019-11-04-1])

・ 「#3844. 比較級の4用法」 ([2019-11-05-1])

・ Crystal, David. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language. Cambridge: CUP, 1995. 2nd ed. 2003. 3rd ed. 2019.

2021-02-14 Sun

■ #4311. 格とは何か? [case][terminology][inflection][category][noun][grammar][sobokunagimon][semantic_role]

格 (case) は,人類言語に普遍的といってよい文法カテゴリーである.系統の異なる言語どうしの間にも,格については似たような現象や分布が繰り返し観察されることから,それは言語体系の中枢にあるものに違いない.

学校英文法でも主格,目的格,所有格などの用語がすぐに出てくるほどで,多くの学習者になじみ深いものではあるが,そもそも格とは何なのか.これに明確に答えることは難しい.ずばり Case というタイトルの著書の冒頭で Blake (1) が与えている定義・解説を引用したい.

Case is a system of marking dependent nouns for the type of relationship they bear to their heads. Traditionally the term refers to inflectional marking, and, typically, case marks the relationship of a noun to a verb at the clause level or of a noun to a preposition, postposition or another noun at the phrase level.

この文脈では,節の主要部は動詞ということになり,句の主要部は前置詞,後置詞,あるいは別の名詞ということになる.平たくいえば,広く文法的に支配する・されるの関係にあるとき,支配される側に立つ名詞が,格の標示を受けるという解釈になる(ただし支配する側が格の標示を受けるも稀なケースもある).

引用中で指摘されているように,伝統的にいえば格といえば屈折による標示,つまり形態的な手段を指してきたのだが,現代の諸理論においては一致や文法関係といった統語的な手段,あるいは意味役割といった意味論的な手段を指すという見解もあり得るので,議論は簡単ではない.

確かに普段の言語学の議論のなかで用いられる「格」という用語の指すものは,ときに体系としての格 (case system) であり,ときに格語尾などの格標示 (case marker) であり,ときに格形 (case form) だったりする.さらに,形態論というよりは統語意味論的なニュアンスを帯びて「副詞的対格」などのように用いられる場合もある.私としては,形態論を意識している場合には "case" (格)という用語を用い,統語意味論を意識している場合には "grammatical relation" (文法関係)という用語を用いるのがよいと考えている.後者は,Blake (3) の提案に従った用語である.後者には "case relation" という類似表現もあるのだが,Blake は区別している.

It is also necessary to make a further distinction between the cases and the case relations or grammatical relations they express. These terms refer to purely syntactic relations such as subject, direct object and indirect object, each of which encompasses more than one semantic role, and they also refer directly to semantic roles such as source and location, where these are not subsumed by a syntactic relation and where these are separable according to some formal criteria. Of the two competing terms, case relations and grammatical relations, the latter will be adopted in the present text as the term for the set of widely accepted relations that includes subject, object and indirect object and the term case relations will be confined to the theory-particular relations posited in certain frameworks such as Localist Case Grammar . . . and Lexicase . . . .

・ Blake, Barry J. Case. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 2001.

2021-01-20 Wed

■ #4286. 双数と中動相をいっぺんに理解できる「対話の作法」 [dual][middle_voice][number][voice][dual][category][greek]

現代英語の学習者にとって馴染みのない文法カテゴリー (category) の成員を紹介したい.数のカテゴリーにおける双数 (両数とも;dual number) と態のカテゴリーにおける中動相 (中動態とも;middle_voice) だ.

いずれも古い印欧諸語に見られるもので,実際,古英語にも人称代名詞には双数がみられたし (cf. 「#180. 古英語の人称代名詞の非対称性」 ([2009-10-24-1])),すでに形骸化してはいたが中動相を受け継ぐ hātan "be called" なる動詞もあった.現代英語ではその伝統は形式的には完全に失われてしまっているが,機能的にいえば対応するものはある.双数には you two, a pair of . . ., a couple などの表現が対応するし,中動相には受動態構文や再帰動詞構文などが対応する.

英語からは形式的に失われてしまった,この双数と中動相の両方をフル活用している言語が,古代ギリシア語である.哲学者の神崎繁が,各々について,また互いの接点についてとても分かりやすく啓発的なエッセイ「対話の作法」を書いている (46--47) .

日本語は,名詞の「単数」と「複数」の区別が明確でないので,英語を学ぶ時,不定冠詞の a をつけるのかつけないのか,語尾に s をつけるのかつけないのか,迷うことになるが,ギリシャ語には,「単数」と「複数」のあいだに,さらに「双数」というのがある.要するに,二つでひと組のものをまとめた表現で,それに合わせて動詞の変化も別にある.目も手も足もそれぞれ二つなので,それらを一組だと考えれば,同じ扱いとなる.

同じく,動詞の能動態・受動態はわかりやすいが(日本語のギリシャ語教育では,どういうわけかそれを相と呼ぶ),「中動相」というのは,純粋に能動とも受動とも言えないもので,たとえば自分の体を洗うとき,はたして自分は洗っているのか,洗われているのか――そういう場合に,「中動相」が使われる.

実はこの「双数」と「中動相」が重なっているものがある.それは「対話」である.対話は,二人の人間が行うものであり,複数の人間のあいだで行われるにしても,その都度,結局二人ずつで行われる.そして,「対話する」という動詞は,「彼ら二人は対話している(ディアレゲストン)」のように,まさに「双数・中動相」で用いられる.つまり,単に「話す」のではなく,同時に「話される」という双方向的な活動なのである.

最近「党首討論」なるものがあるが,あれはお互い一方的に「話す」だけで,「話される」方はすっかり抜け落ちていたような気がする.さて,みなさんは,対話してますか?

うーん,耳が痛い.大学の授業もオンラインでコミュニケーションが一方通行となる傾向が増しており,ディアレゲストンできていない気がする.

以上,双数と中動相がいっぺんに理解できる好例でした.

・ 神崎 繁 「対話の作法」『人生のレシピ 哲学の扉の向こう』 岩波書店,2020年.46--47頁.

2020-11-10 Tue

■ #4215. 強意複数 (2) [plural][intensive_plural][semantics][number][category][noun][terminology][countability][poetry][latin][rhetoric]

昨日の記事 ([2020-11-09-1]) に引き続き強意複数 (intensive_plural) の話題について.この用語は Quirk et al. などには取り上げられておらず,どうやら日本の学校文法で格別に言及されるもののようで,たいていその典拠は Kruisinga 辺りのようだ.それを参照している荒木・安井(編)の辞典より,同項を引用する (739--40) .昨日の記事の趣旨を繰り返すことになるが,あしからず.

intensive plural (強意複数(形)) 意味を強調するために用いられる複数形のこと.質量語 (mass word) に見られる複数形で,複数形の個物という意味は含まず,散文よりも詩に多く見られる.抽象物を表す名詞の場合は程度の強いことを表し,具象物を表す名詞の場合は広がり・集積・連続などを表す: the sands of Sahara---[Kruisinga, Handbook] / the waters of the Nile---[Ibid.] / The moon was already in the heavens.---[Zandvoort, 19757] (月はすでに空で輝いていた) / I have my doubts.---[Ibid.] (私は疑念を抱いている) / I have fears that I may cease to be Before my pen has glean'd my teeming brain---J. Keats (私のペンがあふれんばかりの思いを拾い集めてしまう前に死んでしまうのではないかと恐れている) / pure and clear As are the frosty skies---A Tennyson (凍てついた空のように清澄な) / Mrs. Payson's face broke into smiles of pleasure.---M. Schorer (ペイソン夫人は急に喜色満面となった) / To think is to be full of sorrow And leaden-eyed despairs---J. Keats (考えることは悲しみと活気のない目をした絶望で満たされること) / His hopes to see his own And pace the sacred old familiar fields, Not yet had perished---A. Tennyson (家族に会い,なつかしい故郷の神聖な土地を踏もうという彼の望みはまだ消え去っていなかった) / All the air is blind With rosy foam and pelting blossom and mists of driving vermeil-rain.---G. M. Hopkins (一面の大気が,ばら色の泡と激しく舞い落ちる花と篠つく朱色の雨のもやで眼もくらむほどになる) / The cry that streams out into the indifferent spaces, And never stops or slackens---W. H. Auden (冷淡な空間に流れ出ていって,絶えもしないゆるみもしない泣き声).

同様に,石橋(編)の辞典より,Latinism の項から関連する部分 (477) を引用する.

(3) 抽象名詞を複数形で用いる表現法

いわゆる強意複数 (Intensive Plural) の一種であるが,とくにラテン語の表現法を模倣した16世紀後半の作家の文章に多く見られ,その影響で後代でも文語的ないし詩的用法として維持されている.たとえば,つぎの例に見られるような hopes, fears は,Virgil (70--19 B.C.) や Ovid (43 B.C.--A.D. 17?) に見られるラテン語の amōrēs [L amor love の複数形], metūs [L metus fear の複数形] にならったものとみなされる.Like a young Squire, in loues and lusty-hed His wanton dayes that ever loosely led, . . . (恋と戯れに浮き身をやつし放蕩に夜も日もない若い従者のような…)---E. Spenser, Faerie Qveene I. ii. 3 / I will go further then I meant, to plucke all feares out of you. (予定以上のことをして,あなたの心配をきれいにぬぐい去って上げよう)---Sh, Meas. for M. IV. ii. 206--7 / My hopes do shape him for the Governor. (どうやらその人はおん大将と見える)---Id, Oth. II. i. 55.

ほほう,ラテン語のレトリックとは! それがルネサンス・イングランドで流行し,その余韻が近現代英語に伝わるという流れ.急に呑み込めた気がする.

・ Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech, and Jan Svartvik. A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language. London: Longman, 1985.

・ Kruisinga, E A Handbook of Present-Day English. 4 vols. Groningen, Noordhoff, 1909--11.

・ 荒木 一雄,安井 稔(編) 『現代英文法辞典』 三省堂,1992年.

・ 石橋 幸太郎(編) 『現代英語学辞典』 成美堂,1973年.

2020-11-09 Mon

■ #4214. 強意複数 (1) [plural][intensive_plural][semantics][number][category][noun][terminology][countability]

英語(やその他の言語)における名詞の複数形 (plural) とは何か,さらに一般的に言語における数 (number) という文法カテゴリー (category) とは何か,というのが私の研究におけるライフワークの1つである.その観点から,不思議でおもしろいなと思っているのが標題の強意複数 (intensive_plural) という現象だ.以下,『徹底例解ロイヤル英文法』より.

まず,通常は -s 複数形をとらないはずの抽象概念を表わす名詞(=デフォルトで不可算名詞)が,強意を伴って強引に複数形を取るというケースがある.この場合,意味的には「程度」の強さを表わすといってよい.

・ It is a thousand pities that you don't know it.

・ She was rooted to the spot with terrors.

このような例は,本来の不可算名詞が臨時的に可算名詞化し,それを複数化して強意を示すという事態が,ある程度慣習化したものと考えられる.可算/不可算の区別や単複の区別をもたない日本語の言語観からは想像もできない,ある種の修辞的な「技」である.心理状態を表わす名詞の類例として despairs, doubts, ecstasies, fears, hopes, rages などがある.

一方,上記とは異なり,多かれ少なかれ具体的なモノを指示する名詞ではあるが,通常は不可算名詞として扱われるものが,「連続」「広がり」「集積」という広義における強意を示すために -s を取るというケースがある.

・ We had gray skies throughout our vacation.

・ They walked on across the burning sands of the desert.

・ Where are the snows of last year?

ほかにも,気象現象に関連するものが多く,clouds, fogs, heavens, mists, rains, waters などの例がみられる.

「強意複数」 (intensive plural) というもったいぶった名称がつけられているが,thanks (ありがとう),acknowledgements (謝辞),millions of people (何百万もの人々)など,身近な英語表現にもいくらでもありそうだ.英語における名詞の可算/不可算の区別というのも,絶対的なものではないと考えさせる事例である.

・ 綿貫 陽(改訂・著);宮川幸久, 須貝猛敏, 高松尚弘(共著) 『徹底例解ロイヤル英文法』 旺文社,2000年.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow