2025-11-18 Tue

■ #6049. タスマン海をまたいでアチコチ移動する等語線 [dialectology][dialect][isogloss][new_zealand_english][australian_english][variety][geography][dialect_continuum]

ニュージーランド英語とオーストラリア英語の関係については,通時的に共時的にも様々な議論があり,考察すべき問題が多い.特にニュージーランド英語のほうは,オーストラリア英語にどれほど依存しているのか,あるいはむしろ独立しているのかという論点において,アイデンティティ問題と関わってくるので,議論が熱くなりやすいのだろう.両国の間に横たわるタスマン海 (the Tasman Sea) は,両サイドの英語変種を結びつけている橋のか,あるいは隔てている壁なのか.

この議論と関連して,興味深い事実がある.通常,海や川や山などの自然の障壁は人々の往来を阻みやすいため,そこが言語境界や方言境界となることが多い.とりわけ単語・語法の分布で考えるならば,等語線 (isogloss) が自然の障壁を越えていくことはあまりない,と言ってよい.タスマン海のような地理的に明らかに大きな断絶は,オーストラリア英語とニュージーランド英語を隔てる自然の障壁となるはずだ.

ところが,おもしろいことに,個々の単語・語法によって様相は異なるものの,両変種においては等語線が自然の障壁を越えている例がある.ニュージーランド側から見れば,等語線が国内にはなくタスマン海を西に渡ったオーストラリア側にある,という奇妙な現象が起こっている.

Bauer の挙げている例を見てみよう (413) .

Interestingly enough, some of the isoglosses distinguishing New Zealand English regional dialects cross the Tasman into Australia. Turner . . . comments that the construction boy of O'Brien is also found in Newcastle, New South Wales. Crib is also found meaning 'lunch' in Australia. Small red-skinned sausages are called cheerios in New Zealand, as they are in Queensland, but not elsewhere in Australia . . . . Polony, mentioned above as an Auckland word, is also found in Western Australia . . . . Slater, which is a widespread New Zealand English word, though originally from the South Island, is also found in New South Wales . . . . Blood nose 'nose bleed' is normal in New Zealand, but restricted to Victoria and South Australia in Australia . . . . New Zealand can thus be seen as part of a larger Australasian dialect area in more ways than just sharing vocabulary with Australia.

ちなみに引用内にある polony は「香辛料をたっぷりきかせた豚肉の燻製ソーセージ」,slater は「フナムシ,ワラジムシ」を意味する.食物や動物などの日常語は一般に方言差が出やすく,その点で上記の例も方言学の一般的な傾向を示しているといえるだけに,等語線が海を飛び越えている様が興味深い.

・ Bauer L. "English in New Zealand." The Cambridge History of the English Language. Vol. 5. Ed. Burchfield R. Cambridge: CUP, 1994. 382--429.

2020-08-06 Thu

■ #4119. isogloss ならぬ heterogloss [isogloss][dialectology][dialect][me_dialect][variety][terminology][dialect_continuum]

方言学 (dialectology) では,ある言語項の異形 (variants) の分布を地図上にプロットしてみせる視覚的表現がしばしば利用される.異形がぶつかり合うところは,いわば方言境界をなし,地図上には境界線らしきものが描き出される.この線は,等高線,等圧線,等温線になぞらえて等語線 (isogloss) と呼ばれる.

例えば,言語史上有名の等語線の1つとして「#1506. The Rhenish fan」 ([2013-06-11-1]) で示したドイツ語の maken と maxen に関するものを挙げよう.その方言地図を一目見れば分かる通り,第2次子音推移 (sgcs) を経た南部と経ていない北部がきれいに分割されるような等語線が,東西に一本引かれている.

しかし,「等語線」は一見すると分かりやすい概念・用語だが,実はかなりのくせ者である.1つには,どの単語に注目するかにより等語線の引き方が異なってくるからだ.「#1532. 波状理論,語彙拡散,含意尺度 (1)」 ([2013-07-07-1]) の表で示したとおり,上記の第2次子音推移に関する等語線は,maken/maxen を例にとれば先の地図上の線となるが,ik/ich を例にとればまた別の場所に線が引かれることになる.「#1505. オランダ語方言における "mouse"-line と "house"-line」 ([2013-06-10-1]) の例も同様である.どの単語の等語線を重視すべきかという問題については,「#1317. 重要な等語線の選び方」 ([2012-12-04-1]) で論じたように,ある程度の指標はあるとはいえ,最終的には方言学者の恣意的な判断に任されることになる.

もう1つは,特定の単語に注目した場合ですら,やはりきれいな1本線を地図上に引けるとは限らないことである.例えば,maken は先の等語線の南部ではまったく観察されないかといえば,そうではない.等語線のわずかに南側では用いられているだろう.同じように maxen も等語線のわずかに北側では用いられているはずである.地図上では幅のない1本線で描かれているとしても,その境界は現実の地理においては幅をもった帯として存在しているはずである.つまり,境界線というよりは境界領域といったほうがよい.幅がどれだけ広いか狭いかは別として,その境界領域では両異形が用いられている.

maken と maxen の使用分布を区分する1つの等語線という見方は,ある種の理想化された方言境界を示すものにすぎない.現実には make の南限を示す線と maxen の北限を示す線の,合わせて2本の線があり,両者に挟まれた帯の存在を念頭におかなければならない.換言すれば,この帯をいくぶん太く塗りつぶして1本の線のように見せたのが等語線ということだ.方言学者は,各異形の南限や北限を示す各々の線のことを,"isogloss" と対比させる意味で "heterogloss" と呼んでいる.これについて,中英語方言学の権威 Williamson (489) の説明に耳を傾けてみよう.

An isogloss is a cartographic construct, intended to show the geographical boundary between the distributions of two linguistic features. But the isogloss is problematic: it often distorts what typically happens when the bounds of two distributions meet, by sanitizing or idealizing the co-occurrence of the bounds. There is rarely a clear-cut line between the distributions of features. Rather, they may often overlap, so that there are areas when both forms are used to a greater or lesser extent in neighboring communities or used by the members of one community and understood by those of another. Where the boundaries of features meet, we find zones of transition. It is these zones of transition, shifting across space, which define the dialect continuum.

. . . . An isogloss makes assumptions about what is or is not there. . . . I have resorted to a variant of the isogloss --- the "heterogloss". A heterogloss is a line which attempts to demarcate the bounds of the distribution of a single feature. Where the bounds of the distributions of two features meet, there will be two boundary lines --- one for each feature. Heteroglosses allow us to see where there are overlaps between the distributions.

引用にもある通り,方言連続体 (dialect_continuum) の現実を理解する上でも,"heterogloss" という概念・用語の導入は重要である.関連して「#4114. 方言(特に中英語の方言)をどうとらえるか」 ([2020-08-01-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Williamson, Keith. "Middle English: Dialects." Chapter 31 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 480--505.

2020-08-01 Sat

■ #4114. 方言(特に中英語の方言)をどうとらえるか [me_dialect][dialectology][dialect][variety][geography][isogloss][sociolinguistics][dialect_continuum]

方言 (dialect) をどうみるかという問題は,(社会)言語学の古典的なテーマである.この問題には,言語と方言の区別という側面もあれば,方言どうしの区分という側面もある(cf. 「#4031. 「言語か方言か」の記事セット」 ([2020-05-10-1]),「#1501. 方言連続体か方言地域か」 ([2013-06-06-1])).そもそも方言とは言語学的にいかに定義できるのか,という本質的な問いもある.

英語史研究では中英語方言 (me_dialect) が広く深く調査されてきたが,現在この分野の権威の1人といってよい Williamson (481) が,(中英語)方言とは何かという核心的な問題に言及している.議論の出発点となりそうな洞察に富む指摘が多いので,いくつか引用しておこう.

The most significant and paradoxical finding of dialect geography has been the non-existence of dialects, the objects which it purports to study. A "dialect" is a construct: a reification of some assemblage of linguistic features, defined according to criteria established by the dialectologist. These criteria may be linguistic, extra-linguistic, or some combination of these two kinds.

A (Middle English) dialect can be considered to be some assemblage of diatopically coherent linguistic features which co-occur over all or part of their geographical distributions and so delineate an area within the dialect continuum. Adding or taking away a feature from the assemblage is likely to alter the shape of this area: addition might reduce the area's size, subtraction, increase it. Any text which contains that assemblage of features can be considered as having its provenance within that area.

Linguistic variation across space exists because languages undergo change as a natural consequence of use and transmission from generation to generation of speakers. A linguistic change takes place in a community and subsequently becomes disseminated through time and across space as the next generation of speakers and neighboring communities adopt the change. A "dialect continuum" emerges from the language contacts of speakers in neighboring communities as they share some features, but not others. A continuum is thus made up of a set of overlapping distributions of linguistic features with varied geographical extents --- some extensive, some local. A continuum is not static and is constantly shifting more or less rapidly through time.

特に2つめと3つめの引用は,方言連続体 (dialect_continuum) の精確な定義となっている.この方言観は「#1502. 波状理論ならぬ種子拡散理論」 ([2013-06-07-1]) とも通じるだろう.

・ Williamson, Keith. "Middle English: Dialects." Chapter 31 of English Historical Linguistics: An International Handbook. 2 vols. Ed. Alexander Bergs and Laurel J. Brinton. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 2012. 480--505.

2013-11-11 Mon

■ #1659. マケドニア語の社会言語学 [linguistic_area][map][slavic][history][dialect_continuum][sociolinguistics][ethnic_group]

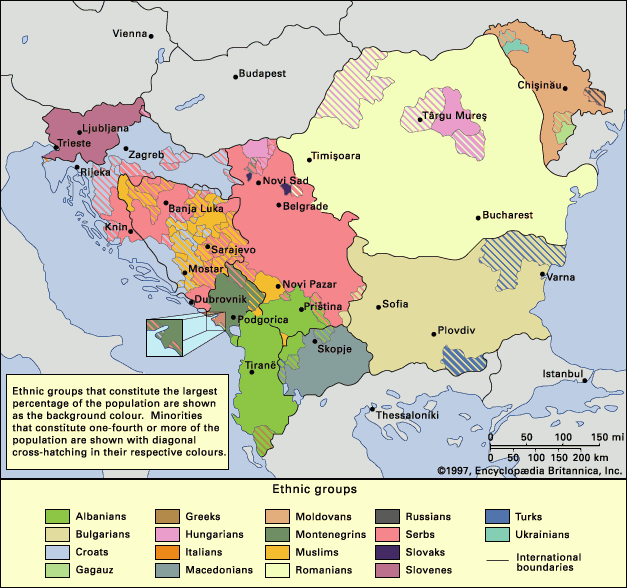

バルカン諸国 (the Balkans) における民族・宗教・言語の分布が複雑なことはよく知られている.バルカン半島は,「#1314. 言語圏」 ([2012-12-01-1]) を形成しており,「#1374. ヨーロッパ各国は多言語使用国である」 ([2013-01-30-1]) の好例となっており,「#1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian」 ([2013-10-19-1]) という社会言語学的な問題を提供しているなどの事情により,社会言語学上,有名にして重要な地域となっている.以下,Encylopædia Britannica 1997 より同地域の民族分布図を以下に掲載する.言語分布図については,今回の話題に関するところとして Ethnologue より Greece and The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia と,「#1469. バルト=スラブ語派(印欧語族)」 ([2013-05-05-1]) で言及した Distribution of the Slavic languages in Europe を挙げておこう.

マケドニア共和国 (The Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia) は,人口約200万を擁するバルカン半島中南部の内陸国である.国民の2/3以上がマケドニア語 (Macedonian) を用いており,公用語となっているが,国内で最大の少数民族であるアルバニア人によりアルバニア語 (Albanian) も話されている(人口統計等は Ethnologue より Macedonia を参照されたい).マケドニア語は South Slavic 語群の言語で,Serbian や Bulgarian と方言連続体を形成している.後述するように,マケドニア語は,この南スラヴの方言連続体と,従属の歴史ゆえに,現在に至るまで言語の autonomy の問題に苦しめられている.

マケドニア人とこの土地の歴史は古い.Alexander the Great (356--23 BC) を輩出した古代マケドニア王国は西は Gibraltar から東は Punjab までの広大な帝国を支配した.古代マケドニア語 (Ancient Macedonian) は南スラヴ系の現代マケドニア語 (Macedonian) とはまったく系統が異なり,またギリシア語とも区別されると言われるが,ギリシア人は古代マケドニア語をギリシア語の1方言とみなしてきた経緯がある.ギリシアはギリシア語の autonomy に対する古代マケドニア語の heteronomy という主従関係を政治的に利用して,マケドニアを自らに従属するものとみなしてきたのである.ギリシア北部には歴史的に Makedhonia を名乗る州もあり,マケドニアにとっては南に隣接するギリシアから大きな政治的圧力を感じながら,国を運営していることになる.実際,ギリシアはマケドニア共和国の独立を,主権侵害とみなしている.

さて,紀元後の話しに移る.マケドニアは6世紀にビザンティン帝国の一部であったが,550--630年の間に,この地にカルパチア山脈の北からスラヴ民族が侵入した.以来,マケドニアの支配的な言語はギリシア語とスラヴ語の間で交替したが,15世紀末にはオスマン帝国の一部に組み込まれた.1912--13年のバルカン戦争ではセルビア人の支配下に入り,1944年にはユーゴスラヴィア共和国へ統合された.この従属の歴史の過程で,マケドニアで話されていた南スラヴ語は,セルビア人にとってはセルビア語の1方言とみなされ,ブルガリア人にとってはブルガリア語の1方言とみなされ,自らの言語的な autonomy を獲得する機会をもつことができなかった.現在でも,セルビア人やブルガリア人はマケドニア語の自立性を,すなわちその存在を認めていない.マケドニアにおいては,政治的従属の歴史は言語的従属の歴史だったといってよい.

このように複雑な歴史をたどってきたにもかかわらず,マケドニアという呼称が土地名,国名,民族名,言語名に共通に用いられていることが問題を見えにくくしている.古代マケドニア語(民族)と現代マケドニア語(民族)は指示対象が異なるというのもややこしい.周辺の3国は,この混乱を利用してマケドニアへの政治的圧力をかけてきたのであり,マケドニア語は,その後ろ盾となるはずの独立国家が成立した後となっても,いまだ不安定な立場に立たされている.autonomy 獲得に向けての道のりは険しい.

以上,Romain (15--17) を参照して執筆した.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2013-10-19 Sat

■ #1636. Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian [sociolinguistics][map][dialect][language_or_dialect][dialect_continuum]

3年前の夏に,ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ (Bosnia and Herzegovina) とクロアチア (Croatia) を旅した.内戦の爪痕の残るサラエボ (Sarajevo) の市街を歩き,洗練された都ザグレブ (Zagreb) を散策し,「アドリア海の真珠」と呼ばれる世界遺産に指定された風光明媚な要塞都市ドゥブロブニク (Dubrovnik) で水浴した.しかし,観光客にとっては平和に見えるこの地域は,現在に至るまで歴史的に争いの絶えない,文字通り世界の火薬庫であり続けてきた.とりわけ1990年代初頭の内乱と続く旧ユーゴスラヴィア解体以来,皮肉にも,この地域は Language is a dialect with an army and a navy. の謂いを最もよく体現する,社会言語学において最も有名な地域の1つとなっている.

1918年に建国した旧ユーゴは当初から多民族・多言語国家だった.北東部のハンガリー語や南西部のアルバニア語を含む少数言語が多く存在したが,主として話されていたのはいずれも南スラブ語群(「#1469. バルト=スラブ語派(印欧語族)」の記事[2013-05-05-1]を参照)の成員であり,互いに方言連続体 (dialect_continuum) を構成していた.マケドニア語方言とスロヴェニア語方言を除き,これら南スラヴ系の方言群は,主要な2民族の名前をとって公式には Serbo-Croatian とひとくくりに呼ばれた.

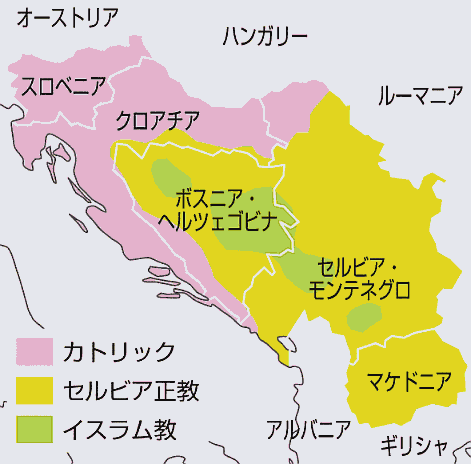

南スラブ民族の団結を目指したこの国は,主として民族と宗教の観点から大きく3派に分れていた.西のクロアチア (Croatia) はカトリック教徒で,表記にラテン文字を用い,経済的にも比較的豊かである.東のセルビア (Serbia) はギリシャ聖教徒であり,キリル文字を用い,政治的には最も優位である(「#1546. 言語の分布と宗教の分布」 ([2013-07-21-1]) を参照).中部のボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナはイスラム教徒が多く,独自の文化をもっている(最新ではないが,この地域の宗教の分布を示す地図を以下に掲げる).このように社会的背景は異なるものの,3者はいずれも同じ Serbo-Croatian を話していた.文法と発音について大きく異なるところがなく,語彙の選択においてそれぞれに好みがあるが,完全に相互理解が可能である.外部から眺めれば,1つの言語とみて差し支えない.

しかし,1990年代初頭に,セルビア人の政治的優勢と専制を嫌って,他の民族が次々と独立ののろしを上げた.1991年に Slovenia と Croatia と Macedonia が,1992年に Bosnia and Herzegovina が独立を宣言した.セルビアとモンテネグロによる新ユーゴスラヴィアは2006年にモンテネグロ (Montenegro) の独立をもって終焉し,さらに2008年にセルビアからコソボ (Kosovo) が独立するという込み入った分裂過程を経ている.

現在のこの地域の言語事情,とりわけ言語名を巡る状況も同様に複雑である.旧ユーゴが解体した以上,旧ユーゴの公式の言語名である Serbia-Croatian を用いることはできない.当然,セルビア人は Serbian と呼びたいだろうし,クロアチア人は Croatian と呼びたいだろう.一方,これらと事実上同じ言語を話すボスニア人にとっては,その言語を Serbia-Croatian, Serbian, Croatian のいずれの名称で指すこともためらわれる.そこで,Bosnian という呼称が新たに生まれることになる.つまり,旧ユーゴ分裂という政治的な過程により,言語学的には1つとみなされてよい(実際に1つとみなされていた)言語が,名称上3つの異なる言語 (Serbian, Croatian, Bosnian) へと分かれたのである.まさに,Language is a dialect with an army and a navy である.

政治的に分離してからは,セルビアとクロアチアは「#1545. "lexical cleansing"」 ([2013-07-20-1]) の政策に従い,互いに相手の言語を想起させる語彙を新聞や教科書から排除するという言語計画を進めてきた.両者はまたトルコ系語彙の排除も進めているが,ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナではむしろトルコ系語彙を好んで使うようになっている.

以上,Trudgill (46--48) および Wardhaugh (27--28) を参照して執筆した.

・ Trudgill, Peter. Sociolinguistics: An Introduction to Language and Society. 4th ed. London: Penguin, 2000.

・ Wardhaugh, Ronald. An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 6th ed. Malden: Blackwell, 2010.

2013-06-27 Thu

■ #1522. autonomy と heteronomy [sociolinguistics][dialect][variety][terminology][language_or_dialect][dialect_continuum]

言語学および社会言語学の古典的な問題の1つに,言語 (language) と方言 (dialect) の境界という問題がある.この境界を言語学的に定めることは,多くの場合,きわめて難しい([2013-06-05-1]の記事「#1500. 方言連続体」を参照).この区別をあえてつけなくて済むように "a linguistic variety" (言語変種)という便利な術語が存在するのだが,社会言語学的にあえて概念上の区別をつけたいこともある.その場合,日常用語として実感の伴った「言語」と「方言」という用語を黙って使い続けてしまうという方法もあるが,それでは学問的にあえて区別をつけたいという主張が薄まってしまうきらいがある.

そこで便利なのが,標題の autonomy と heteronomy という一対の概念だ.autonomous な変種とは,内からは諸変種のなかでもとりわけ権威ある変種としてみなされ,外からは独立した言語として,すなわち配下の諸変種を束ねあげた要の変種を指す.一方,heteronomous な変種とは,内からも外からも独立した言語としての地位を付されず,上位にある autonomous な変種に従属する変種を指す.比喩的にいえば,autonomy とは円の中心であり,円の全体でもあるという性質,heteronomy とはその円の中心以外にあって,中心を指向する性質と表現できる.

この対概念をよりよく理解できるように,Trudgill の用語集からの説明を示そう.

autonomy A term, associated with the work of the Norwegian-American linguist Einar Haugen, which means independence and is thus the opposite of heteronomy. Autonomy is a characteristic of a variety of a language that has been subject to standardisation and codification, and is therefore regarded as having an independent existence. An autonomous variety is one whose speakers and writers are not socially, culturally or educationally dependent on any other variety of that language, and is normally the variety which is used in writing in the community in question. Standard English is a dialect which has the characteristic of autonomy, whereas Cockney does not have this feature. (12)

heteronomy A term associated with the work of the Norwegian-American linguist Einar Haugen. Dependence --- the opposite of autonomy. Heteronomy is a characteristic of a variety of a language that has not been subject to standardisation, and which is not regarded as having an existence independent of a corresponding autonomous standard. A heteronomous variety is typically a nonstandard variety whose speakers and writers are socially, culturally and educationally dependent on an autonomous variety of the same language, and who look to the standard autonomous variety as the one which naturally corresponds to their vernacular. (58)

日常用語としての「言語」と「方言」が指示するものの性質をそれぞれ autonomy vs heteronomy として抽出し,その性質を形容詞 autonomous vs heteronomous として記述できるようにしたのが,この新しい概念と用語の利点だろう.言語と方言の区別,標準変種と非標準変種の区別という問題を,社会的な独立と依存という観点からとらえ直した点が評価される.関連して,Romain (14--15) の解説も有用.

・ Trudgill, Peter. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: OUP, 2003.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

2013-06-06 Thu

■ #1501. 方言連続体か方言地域か [dialect_continuum][geography][dialect]

昨日の記事「#1500 方言連続体」 ([2013-06-05-1]) で,方言連続体 (dialect continuum) と方言地域 (dialect area) の関係を巡る理論的な問題に触れた.その際に Heeringa and Nerbonne に言及したが,彼らは計量的な手法でこの問題に迫ろうとした.Heeringa and Nerbonne は,西ゲルマン方言連続体の一部をなすオランダ北東岸に沿った27の村々を対象に20世紀に行なわれた方言調査(Reeks nederlands(ch)e dialectatlassen (RND) comp. Blancquaert and Peé (1925--82)) のデータに基づいて,125を超える語彙項目の音韻変異に注目し,計量分析を施した (dialectometry) .音韻変異の幅を測定する方法としては,"Levenshtein distance" が採用されている.

分析の詳細は割愛するが,結論としては地理的な距離と音韻変異の幅の間に強い相関関係があることが示された.

There is a strong correlation between the phonological distance and the logarithm of geographic distance (.9), accounting for 81% of the variation in pronunciation. (396)

ただし,強い相関関係があるとはいっても,完全な相関関係ではない以上,すべての隣村どうしが同じようにスムーズな連続体をなすわけではなく,多少のでこぼこがある.つまり,隣り合う2つの村の間にある程度の断絶が認められるケースがあり,その場合,想像上の断絶線の両側には異なる方言地域が広がっていると考えることもできるわけである.

. . . we see that phonological distances can mostly be explained by geographic distance. This justifies the continuum perspective. In those cases where a dialect distance between successive points is significantly higher than would be expected on the basis of geographic distances, we may encounter a dialect border. This justifies the area perspective. (387)

方言連続体と方言地域とは理論的に相容れない概念のように思われるかもしれないが,いずれの概念も言語的な差分は前提としているのである.その差分を限りなく小さいものとみれば連続性を語れるし,比較的大きいものとみれば断絶を,すなわち方言地域を語れることになる.つまるところ見方の問題であり,程度の問題ということなのかもしれない.Heeringa and Nerbonne の結論も,この理論的問題がとらえ方の問題であることを指摘している.

. . . the dialect landscape . . . may be described as a continuum with varying slope or, alternatively, as a continuum with unsharp borders between dialect areas. (399)

・ Heeringa, Wilbert and John Nerbonne. "Dialect Areas and Dialect Continua." Language Variation and Change 13 (2001): 375--400.

2013-06-05 Wed

■ #1500. 方言連続体 [dialect_continuum][dialect][geography][isogloss][map][terminology][language_or_dialect]

方言どうしの境界線(あるいは時に言語どうしの境界線)は,必ずしも明確に引けるとは限らない.否,多くの場合,方言線は多かれ少なかれ恣意的である.「#1317. 重要な等語線の選び方」 ([2012-12-04-1]) で述べたように,等語線 isogloss が太い束をなすところに境界線が引かれるとするのが一般的ではあるが,絶対的な基準はないといってよい.

ある旅行者が地理的に連続体をなすA村からZ村へと歩いてゆく旅を想像すると,A村の言語とB村の言語とは僅少な差しかなく,B村とC村,C村とD村も同様だろう.旅行者は,各々の言語的な差異にはほとんど気付かずに歩いて行き,ついにZ村に達する.ところが,客観的にA村とZ村の言語を比べると,明らかに大きな差異があるのである.村から村への言語差はデジタルではなくアナログであり,旅行者が体験したのは方言連続体 (dialect continuum) にほかならない.世界各地に方言連続体が存在するが,ヨーロッパだけを見ても複数の方言連続体が見られる.以下は,Romain (12) の図を参考にして作った方言連続体の地図である.

この地図は,例えばイタリア南端からフランス北部のカレーまで,あるいはアムステルダムからウィーンまで,方言連続体を旅することができるということを意味する.

方言連続体を示す地域の限界は,波線で示された国境線と一致することもあれば一致していないこともある.これは,隣り合う2つの村が国境を挟んでいるからといって,必ずしも大きく異なる言語を用いているというわけではないということを示すと同時に,場合によっては同一国内の隣り合う2つの村でも言語の断絶があり得るということを示す.

方言連続体に関しては,理論的な問題がある.A, B, C, . . . Zの村々が方言連続体を構成していると想定した場合,それぞれの村の内部では一様な言語が行なわれていると考えてよいのだろうか.あるいは,村の西端と中央と東端とではミクロな方言連続体が存在しているのだろうか.もしA村とB村がそれぞれ言語的に一様だと仮定するならば,A村は1つの方言地域 (dialect area) を構成し,B村はもう1つの方言地域を構成するということになり,A村の方言とB村の方言の間には連続体ではなく小さいながらも断絶が想定されるということにならないだろうか.方言連続体という概念と方言地域という概念はどのように関連しているのだろうか.この理論的問題は,Chambers and Trudgill の問題として,Heeringa and Nerbonne によって取り上げられている.

Chambers and Trudgill (1998) introduced an interesting puzzle, one that is related to whether dialects should be viewed as organized by areas or via a geographic continuum. They observed that a traveller walking in a straight line notices successive small changes from village to village, but seldom, if ever, observes large differences. This sounds like a justification of the continuum view . . . . (376)

いかに方言連続体が生じるか,なぜ方言が存在するのかという問題については,「#1303. なぜ方言が存在するのか --- 波状モデルによる説明」 ([2012-11-20-1]) の記事も参照.

・ Romain, Suzanne. Language in Society: An Introduction to Sociolinguistics. 2nd ed. Oxford: OUP, 2000.

・ Heeringa, Wilbert and John Nerbonne. "Dialect Areas and Dialect Continua." Language Variation and Change 13 (2001): 375--400.

・ Chambers, J. K. and Peter Trudgill. Dialectology. 2nd ed. Cambridge: CUP, 1998.

2012-11-20 Tue

■ #1303. なぜ方言が存在するのか --- 波状モデルによる説明 [dialect][family_tree][wave_theory][geography][isogloss][dialect_continuum][sobokunagimon]

昨日の記事「#1302. なぜ方言が存在するのか --- 系統樹モデルによる説明」 ([2012-11-19-1]) に引き続き,なぜ方言が存在するのか,なぜ方言が生まれるのかという素朴な疑問に迫る.昨日述べた系統樹モデル (family_tree) による説明の欠陥を補いうるのが,波状モデル (wave_theory) だ.

Bloomfield (317) の記述を借りて,波状モデルによる方言分化の説明としよう.

Different linguistic changes may spread, like waves, over a speech-area, and each change may be carried out over a part of the area that does not coincide with the part covered by an earlier change. The result of successive waves will be a network of isoglosses . . . . Adjacent districts will resemble each other most; in whatever direction one travels, differences will increase with distance, as one crosses more and more isogloss-lines. This, indeed, is the picture presented by the local dialects in the areas we can observe.

ここで前提とされているのは,(1) 言語変化(言語的革新)が次々と生じ,波状に拡散することと,(2) 個々の言語変化によって波の到達範囲が異なることだ.この2点により,方言地理のカンバスには,複雑に入り組んだ等語線 (isogloss) が引かれることになる.任意の2地点をとると,互いに近ければ近いほど,過去の言語変化を多く共有しているので,全体として言語的な共通点が多く,近い方言を話すことになる.逆に遠ければ遠いほど,歴史的に共有してきた言語変化は少ないので,全体として違いの大きい方言を話すことになる.後者のケースでは,時間が経てば経つほど,言語的な共通点が少なくなり,最終的には互いに通じない異なる言語へと分化してゆく.

このように,波状モデルは,時間軸に沿った分岐と独自変化よりも,地理的な距離に基づく類似と相違という点を強調する.方言の分化を説明するのにより優れたモデルとされているが,系統樹モデルに基づく比較言語学も相当の成功を収めてきたのは事実であり,両モデルを相補い合うものとしてとらえるのが妥当だろう.いずれのモデルにおいても,言語変化の普遍性,遍在性が前提とされていることは銘記しておきたい.

Bloomfield (317--18) は上の引用に続けて,波状モデルによる方言分化について,より突っ込んだ理論的な視点から解説を与えている.こちらも引用しておこう.

Now, let us suppose that among a series of adjacent dialects, which, to consider only one dimension, we shall designate as A, B, C, D, E, F, G, . . . X, one dialect, say F, gains a political, commercial, or other predominance of some sort, so that its neighbors in either direction, first E and G, then D and H, and then even C and I, J, K, give up their peculiarities and in time come to speak only the central dialect F. When this has happened, F borders on B and L, dialects from which it differs sharply enough to produce clear-cut language boundaries; yet the resemblance between F and B will be greater than that between F and A, and, similarly, among L, M, N, . . . X, the dialects nearest to F will show a greater resemblance to F, in spite of the clearly marked boundary, than will the more distant dialects. The presentation of these factors became known as the wave-theory, in contradistinction to the older family-tree theory of linguistic relationship. Today we view the wave process and the splitting process merely as two types --- perhaps the principal types --- of historical processes that lead to linguistic differentiation.

・ Bloomfield, Leonard. Language. 1933. Chicago and London: U of Chicago P, 1984.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow