2017-10-05 Thu

■ #3083. 「英語のスペリングは大聖堂のようである」 [spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

Simon Horobin 著 Does Spelling Matter? のほぼ最後の部分で,著者は英語のスペリングを長い歴史を誇る大聖堂になぞらえている.原文および,堀田による邦訳『スペリングの英語史』からの該当箇所を引用する.

Our spelling system could be likened to a cathedral church, whose origins lie in the Anglo-Saxon period, but whose structure now includes a Gothic portico added in the Middle Ages, a domed tower added in the Early Modern period, and a gift shop and café introduced in the 1960s. The end result is an awkward mixture of architectural styles which no longer reflects the builders' original plan, nor is it the ideal building for the bishop and his clergy to carry out their diocesan duties. But, in spite of these practical limitations, it would be hard to imagine anyone suggesting that the cathedral be demolished to allow the rebuilding of a more functional and architecturally harmonious modern construction. Quite apart from the practical and financial costs of such a project, the demolition and reconstruction of the cathedral would erase the rich historical record that such a building represents. (249)

われわれのスペリング体系は大聖堂になぞらえることができる.アングロサクソン時代に起源をもち,中世に継ぎ足されたゴシック様式の柱廊玄関の構造をもち,初期近代期にドーム状の塔が建て増しされ,1960年代にギフトショップとカフェが導入された大聖堂だ.結果としてできたものは,もはや建築家の当初の計画を反映していないぎこちない混合体であり,主教や聖職者が教区の業務を行なうのに理想的な建物でもない.しかし,このような実用上の制限はあるにせよ,取り壊してもっと機能的で建築学上調和の取れた現代的な構造にするための建て直しを許可すべきだと提案する人がいるとは想像しがたいだろう.そのような計画にかかる実際的で財政的なコストのことはまったく別にしても,大聖堂の取り壊しと建て直しによって,こうした建物が体現する豊かな歴史の記録が消されてしまう. (276--77)

この箇所を初めて読んだとき,著者 Simon Horobin 氏のなかに,イギリス(文献学)一流の保守的伝統をまざまざと見せつけられた思いがした.著者は英語史・中世英語英文学の研究者であるから,歴史を重視する立場にあるだろうことは当然予想されるところだが,実際その立場は読者が誤解し得ないほどに明白である.スペリング改革の可能性を否定する著者の考え方もここから発しているし,現行のスペリング体系を積極的に維持する著者の態度も同様である.

一方で,「#3081. 日本の英語学習者のための『スペリングの英語史』の読み方」 ([2017-10-03-1]) でも評したように,著者は「複数の正書法」 (orthographies) の可能性を見据えているようにも思われる.つまり,著者は,現代にふさわしい柔軟なスペリングのあり方を模索してもいるのだ.あくまで伝統を保ちながら,変異と多様性を取り込み,徐々に変化を進めていく.まさにイギリス流保守本流の考え方そのものである.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-10-04 Wed

■ #3082. "spelling bee" の起源と発達 [spelling][ame][history][webster][word_play][spelling_bee]

Simon Horobin 著 Does Spelling Matter? (堀田による邦訳『スペリングの英語史』も参照)で,いろいろな形で取り上げられているが,アメリカでは伝統的にスペリング競技会 "spelling bee" が人気である.

スペリング競技会の起こりはエリザベス朝のイングランドにあるが,注目される行事へと発展したのは,独立後のアメリカにおいてであった.Webster のスペリング教本 "Blue-Backed Speller" のヒットに支えられ,アメリカの国民的イベントへと成長した.Webster の伝記を著した Kendall (106--07) が,スペリング競技会の歴史について次のように述べている.

Webster's speller also gave rise to America's first national pastime, the spelling bee. Before there was baseball or college football or even horse racing, there was the spectator sport that Webster put on the map. Though "the spelling match" first became a popular community event shortly after Webster's textbook became a runaway best seller, its origins date back to the classroom in Elizabethan England. In his speller, The English Schoole-Maister, published in 1596, the British pedagogue Edmund Coote described a method of "how the teacher shall direct his schollers to oppose one another" in spelling competitions. A century and a half later, in his essay, "Idea of the English School," Benjamin Franklin wrote of putting "two of those [scholars] nearest equal in their spelling" and "let[ting] these strive for victory each propounding ten words every day to the other to be spelt." Webster's speller transformed these "wars of words" from classroom skirmishes into community events. By 1800, evening "spelldowns" in New England were common. As one early twentieth-century historian has observed:

The spelling-bee was not a mere drill to impress certain facts upon the plastic memory of youth. It was also one of the recreations of adult life, if recreation be the right word for what was taken so seriously by every one. [We had t]he spectacle of a school trustee standing with a blue-backed Webster open in his hand while gray-haired men and women, one row being captained by the schoolmaster and the other team by the minister, spelled each other down.

綴字と発音の乖離がみられる英単語のスペリング競技会で勝つためには,並外れた暗記力と語源的な知識が試される.ある意味で,英語らしいイベントといえるだろう.

・ Kendall, Joshua. The Forgotten Founding Father. New York: Berkeley, 2012.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-10-03 Tue

■ #3081. 日本の英語学習者のための『スペリングの英語史』の読み方 [notice][toc][spelling][hel][review]

拙訳『スペリングの英語史』について,もちろん好きなように読んでいただけば,それだけで嬉しいわけでして,実におせっかいな記事のタイトルなのですが,原著 Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013. の日本人読者の1人として,また英語の学習者・研究者の1人として,次のようなことを考えながら読み,訳してきたということを文章に残しておきたいと思いました.ポイントは3点あります.

1つ目は,本書が日本の英語学習者にスペリング学習に際しての知識を与えてくれるということです.とはいうものの,著者は意外なことに,序章の最後で,本書はスペリング学習に役立つ実用書ではないことを示唆しています.そのような目的で本書を手に取った読者がいたとすれば,おそらく幻滅するだろうと.確かに,本書で英語のスペリングの波乱の歴史を知ってしまうと,むしろなぜ現在のスペリングがこれほど無秩序であり,少数の規則で説明しきれないのかがよくわかってしまいます.言語的には英語のスペリングのすべてを説明づけられるような少数の規則はないといってよく,それに気づいた読者は,英語のスペリングを学習する上での絶対的な便法はやはりないのか,と悲観的に結論づけざるをえないかのようです.

しかし,著者は(そして訳者も)英語のスペリングがそこまで無秩序で不規則だとは考えていません.おそらく,スペリングの規則というものがあるとすれば,スペリングの歴史全体がその規則であるという立場をとっています.現在のスペリングだけを観察して,そこから何らかの規則を抽出しようとしても,たちどころに例外や不規則が現われてしまい,むしろ最初から個別に扱ったほうがよかった,という結果になりがちです.しかし,スペリングの歴史をたどってみると,確かに無数の込み入った事情はあったけれども,その事情のひとつひとつは多くの場合納得して理解できるものだとわかります.余計な文字をスペリングに挿入したルネサンスの衒学者の気持ちも説明されればわかりますし,ノア・ウェブスターがスペリング改革を提案した理由も,アメリカ独立の時代背景を考慮すれば腑に落ちます.このような個々の歴史的な事情を指して「規則」とは通常呼びませんが,「e の前の音節の母音字は長い発音で読む」のような無機質な規則に比べれば,ずっと人間的で有機的な「規則」と言えないでしょうか.このような歴史に起因する「規則」は必然的に雑多ではありますが,それにより現在のスペリングの大多数が説明できるのです.歴史を学ぶことは遠回りのようでいて,しばしば最も納得のゆく方法です.本書では,便法としての規則は必ずしも得られなくとも,納得のゆく説明は得られます.説得力,それが本書のもつ最大の価値です.

また,歴史こそが規則であるという著者のスタンスは,著者のスペリング改革に対する懐疑的で批判的な立場とも符合します.完全に表音的なスペリングへ改革してしまうと,スペリングの表面から歴史という規則の痕跡が消し去られてしまうからです.

本書が日本の読者にとってもつもう1つの意義は,英語の書記体系を鑑として,私たちの母語である日本語の書記体系について再考を促してくれる点にあります.読者は本書を読みながら,英語のスペリングと比較対照させつつ日本語の書記体系にも思いを馳せるでしょう.日本語は珍しく唯一絶対の正書法がない言語といわれます(cf. 「#2392. 厳しい正書法の英語と緩い正書法の日本語」 ([2015-11-14-1]),「#2409. 漢字平仮名交じり文の自由さと複雑さ」 ([2015-12-01-1])).ニャーニャー鳴く動物を表記せよと言われれば,「猫」「ネコ」「ねこ」「neko」のいずれも可能です.もちろん用いる文字種が指定されれば1つの書き方に定まりますが,原則としてどの文字種を用いるかは書き手に委ねられています.書き手のその時の気分によって,求められている文章の格式によって,想定される読み手が誰かによって,あるいはまったくのランダムで,自由に書き分けることが許されます.ここには,書き手の選択の自由があり,正書法上の「遊び」があります.

本書の第4章で触れられるように,1100年から1500年の英語,中英語では同じ単語でも書き手個人ごとに異なるスペリングがあり,さらに個人においても複数の異綴りを用いるのが普通でした.ここにも「遊び」があったのです.日本語と中英語では「遊び」の質も量も異なり,一概に比較できませんが,書き手に選択の自由が与えられていることは共通しています.正確に発音を表わすことが重要な場合,単語の意味が同定できさえすればよい場合,書き手が気分を伝えたい場合,読み手に対して気遣いする場合など,様々なシーンで,書き手は書き方を選ぶことができます.文字は言葉の発音や意味などを伝える手段であると同時に,使用者が自らの気分やアイデンティティを伝える手段でもあります.確かに唯一絶対の正書法は,広域にわたる公共のコミュニケーションのためには是非とも必要でしょう.しかし,公表を前提としない個人的な買い物リストのメモ書きや,字数制限のあるツイッターの文章を含めたあらゆる書き言葉の機会において,常に唯一絶対の正書法に従わなければならないとすれば,いかにも息苦しいし,書き手の個性を消し去ることにならないでしょうか.

後期古英語の標準的なスペリング体系のもとではそれほど許されなかった「遊び」が,中英語期にはいきいきと展開しましたが,続く近代英語期には再び制限を加えられていきました.このような歴史を学ぶことは,いまだ「遊び」を保持している日本語書記体系の現在と未来を考え,議論する上で貴重な洞察を与えてくれます.英語のスペリング改革史においてほとんどの提案が失敗に終わったという事実も,日本語の書記体系の行く末を考える上で示唆的です.逆に日本語の立場から英語をみると,日本語は1つのモデルケースということになるかもしれません.というのは,著者は英語について「1つの正書法」 (the orthography) ではなく「複数の正書法」 (orthographies) の可能性を探っている節があるからです,

本書の3つ目の意義は,文字にも歴史があるという当たり前の事実を再認識させてくれる点にあります.本書は,現在ある文字や言葉は,それがたどってきた歴史の産物であるという事実を改めて教えてくれます.文字という小さな単位を入り口に,言葉の歴史という広い世界へと案内してくれる書だと思います.英語に関する読み物にとどまっておらず,言葉に関する教養の詰まった本となっています.この点は,一般読者だけではなく,言葉を専門とする言語学者や英語学者に対しても力説しておきたいポイントです.

20世紀の言語研究では,歴史的視点が欠如していました.また,音声を重視するあまり,文字が軽んじられてきました.つまり,スペリングの歴史という話題は,20世紀の主流派の言語研究において,最も軽視されてきたテーマの1つといってよいでしょう.本書を通じて,一般読者と専門の言語学者が,文字の言語学および歴史的な視点をもった言語学のおもしろさと価値を再認識してくれることに期待したいと思います.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-10-02 Mon

■ #3080. 『スペリングの英語史』の章ごとの概要 [notice][toc][spelling][hel]

昨日の記事「#3079. 拙訳『スペリングの英語史』が出版されました」 ([2017-10-01-1]) で拙訳書の目次を挙げた.今回は章ごとの概要を示しつつ,『スペリングの英語史』のガイドとしたい.事実上,英語スペリング史の概略となっている.

1. 「序章」.正書法(正しいスペリング)を巡る近年の議論を参照しながら,多くの人が当然視する唯一絶対のスペリングは本当に必要なのかという問題提起がなされる.たとえば,元アメリカ合衆国副大統領ダン・クウェールの potato 事件に象徴されるように,スペリングを1文字間違えるだけで社会的制裁が加えられるような現代の風潮は異常ではないかと.このような問題の背景には,英語のスペリングが無秩序で不規則であるという世間一般の評価がある.有意義な議論のためには,英語のスペリングの歴史を知っておくことが重要である.

2. 「種々の書記体系」.人類の文字の起源から説き起こし,世界各地の書記体系を紹介しつつ,文字と意味あるいは文字と発音の関係について理論的に考察する.中世ヨーロッパの文字理論を援用し,またベル考案の視話法や『指輪物語』の架空の文字に言及しながら,英語表記に用いられているローマン・アルファベットが原則として表音的な性質をもちつつも,必ずしも理想的な表音文字としては機能していないことを指摘し,英語のスペリング体系が発音との間にギャップを示す「深い正書法」であると説く.最後に,スペリングが言語において最も規制の対象となりやすい側面であることを指摘しつつ,標準的なスペリング体系のもつ社会的役割を論じる.

3. 「起源」.6世紀末に英語にローマン・アルファベットがもたらされる以前からアングロサクソン世界で用いられていた,もう1つのアルファベット体系,ルーン文字が紹介される.最古の英文は,実にルーン文字で書かれていたのである.やがてローマン・アルファベットがルーン文字に取って代わったが,文字の種類や書体は現在われわれが見慣れているものと若干異なっていた.古英語アルファベットの示す文字と発音の関係は,それに先立つラテン文字,エトルリア文字,ギリシア文字などから受け継いだものと,古英語での改変を反映したものの混合であり,古英語のスペリングもすでに複雑ではあったものの,後期古英語にはウェストサクソン方言を基盤とした標準的なスペリング体系が整えられていった.古英語のスペリングの実例が,聖書や『ベーオウルフ』からの引用により示される.

4. 「侵略と改正」.1066年のノルマン征服により後期古英語の標準語が崩壊し,続く中英語期には多種多様な方言スペリングが花咲いた.これにより,through や such のような単語は,写字生の方言によってきわめて多様に(約500通りにも)綴られることになった.また,中英語期には,フランス語の習慣の影響を受けて書体やスペリングに少なからぬ改変が加えられた.初期中英語には,標準的なスペリングらしきものが芽生えた証拠もあるが,それらは特定の個人や集団に限定されており,真の標準とはなりえなかった.しかし,後期中英語になると現代に連なる標準的なスペリングの原型が徐々に現れだした.このような自由奔放で変異に満ちた中英語のスペリングは,唯一絶対のスペリングを当然視する現代のスペリング観に真っ向から対立するものである.

5. 「ルネサンスと改革」.初期近代英語期は,異綴りが減少し,標準的なスペリング体系が形成されていく時代である.人々がスペリングの問題を意識するようになり,特にスペリング改革者,教育関係者,印刷業者が各々の思惑のもとにスペリングのあり方を論じ,実践した.ルネサンスの衒学者たちは,ラテン語の語源を反映するスペリングを好み,たとえば doubt のスペリングに b を挿入し保存すること主張した.理想主義的な理論家たちは,文字と発音の関係が緊密であるべきことを説き,新たな文字や記号を導入する過激なスペリング改革を提案した.もっと穏健な論者たちは,従来から行なわれてきたスペリングの慣習を,必ずしも合理的でなくとも許容し,定着させようと努力した.結果的に,穏健派のリチャード・マルカスターの提案が後世のスペリングに影響を与えることとなった.

6. 「スペリングの固定化」.18世紀は,スペリングをはじめ英語を固定化することに腐心した時代だった.スウィフトによる英語アカデミー設立の試みは失敗したものの,1755年にはジョンソンが後世に多大な影響を及ぼすことになる『英語辞典』を世に送り出し,標準的なスペリングを事実上確定させた.しかし,スウィフトやジョンソンも,印刷された公の文書においてこそ標準的なスペリングを用いていたものの,私信などの手書き文書においては非標準的なスペリングも用いており,個人のなかでもいまだ異綴りが見られた.続けて,19世紀後半から20世紀前半にかけての『オックスフォード英語辞典』 (OED) の編者マレーやブラッドリーのスペリングに対する姿勢が概説され,20世紀の「カット・スペリング」「規則化英語」「ショー・アルファベット」「初等教育アルファベット」といったスペリング改革案やスペリング教育法の試みが批判的に紹介される.

7. 「アメリカ式スペリング」.ノア・ウェブスターによるスペリング改革の奮闘が叙述される.この英語史上稀なスペリング改革の成功の背景には,提案内容が colour を color に変えるなど穏健なものであったこと,スペリング本が商業的に成功したこと,そして新生アメリカに対する国民の愛国心がおおいに関与していたことが指摘される.そのほか,アメリカにおけるスペリング競技会の人気振りやトウェインのスペリング観に言及するとともに,アメリカの単純化スペリング委員会の検討したスペリング改革案について,規範的発音を前提とする誤った言語観に基づいているとして批判を加えている.

8. 「スペリングの現在と未来」.近年の携帯メールにみられる省略スペリングの話題が取り上げられる.著者は,省略スペリングの使用者が使い分けをわきまえていることを示す調査結果や,中世にも同様の省略スペリングが常用されていた事実を挙げながら,省略スペリングが多くの人が心配しているように教育水準が下がっている証拠ともならなければ,規範的なスペリングがないがしろにされている証拠ともならないと反論する.綴り間違いに不寛容な態度を示す現代の風潮を批判し,英語のスペリングは英語がたどってきた豊かな歴史の証人であり,今あるがままに保存し尊重すべきであると述べて本書を結ぶ.

以上,現代英語のスペリングが壮大な歴史の上に成り立っていることがわかるだろう.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-10-01 Sun

■ #3079. 拙訳『スペリングの英語史』が出版されました [notice][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][history][hel_education][toc][link]

9月20日付で,拙訳『スペリングの英語史』が早川書房より出版されました.原著は本ブログで何度も参照・引用している Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013. です.本ブログを読まれている方,そして英語スペリングの諸問題に関心をもっているすべての方に,おもしろく読んでもらえる内容です.

|

| サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.302頁.ISBN: 978-4152097040.定価2700円(税別). |

「本書をただのスペリングの本だと思ったら大間違いである.ここには,英語史,英文学をはじめ,英語の教養がぎっしりと詰まっている」との推薦文を,東大の斎藤兆史先生より寄せていただきました.また,本書の帯に「オックスフォード大学英語学教授による,スペリングの謎に切り込む名解説」という売り文句がありますが,訳者も英語のスペリングに関する読ませる本としては最高のものであると確信しています(もう1冊の読ませるスペリング本として,Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012. も薦めます).

本書には,このスペリングやあのスペリングの背景にこんな歴史的な事件が関与していたのか,と驚くエピソードが満載です.例えば・・・

・ 合衆国副大統領の政治生命の懸かった,potato のスペリングをめぐる醜聞

・ 『指輪物語』のトールキンは,独自のアルファベット体系を考案し,それで日記をつけていた

・ 最古の英文はローマ字ではなくルーン文字で書かれていた

・ 中英語期には such の異なるスペリングが500種類もあった

・ ルネサンス期のラテン語かぶれの知識人が,doubt の <b> のような妙なスペリングの癖を生み出した

・ シェイクスピア『リア王』で語られる,英語における <z> の文字の冷遇

・ Smith さんか,Smythe さんか,はたまた Psmith さんか --- 名前のスペリングへのこだわり

・ みずからの遺産を理想的なアルファベット考案の賞金にあてた劇作家バーナード・ショー

・ ウェブスターがアメリカ式スペリングの改革に成功したのは,独立の愛国心とベストセラー『スペリング教本』の商業的成功ゆえ

・ 電子メールに溢れる省略スペリングは,英語の堕落の現われか,言語的創造力のたまものか

本書の目次は,以下の通りとなっています.

日本版への序文

図一覧

発音記号

1 序章

2 種々の書記体系

3 起源

4 侵略と改正

5 ルネサンスと改革

6 スペリングの固定化

7 アメリカ式スペリング

8 スペリングの現在と未来

読書案内

参考文献

訳者あとがき

語句索引

原著の著者ついて,簡単に紹介しておきます.サイモン・ホロビン氏はオックスフォード大学モードリン・カレッジ・フェローの英語学教授です.英語史・中世英語英文学を専門としており,以下のような主要著書を世に送り出してきました.まさに気鋭の英語史研究者です.

・ Horobin, Simon and Jeremy Smith. An Introduction to Middle English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2002.

・ Horobin, Simon. The Language of the Chaucer Tradition. Cambridge: Brewer, 2003.

・ Horobin, Simon. Chaucer's Language. 1st ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. 2nd ed. 2012.

・ Horobin, Simon. Studying the History of Early English. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009.

・ Horobin, Simon. How English Became English: A Short History of a Global Language. Oxford: OUP, 2016.

また,最近はあまり更新されていないようですが,著者は2012年から Spelling Trouble という英語のスペリングの話題を提供するブログで,いくつかの記事を書いています.

ちなみに個人的なことをいえば,訳者はグラスゴー大学に留学し2005年に博士号を取得しましたが,当時,著者はグラスゴー大学で教鞭を執っており,訳者の学位審査官の1人でもありました.あのときもお世話になり,このたびもお世話になり,という経緯です.さらに,2年前の2014年12月には,本書にインスピレーションを受けて開催したシンポジウムに著者を招き,英語のスペリングについて一緒に議論する機会をもつことができました(cf. 「#2053. 日本中世英語英文学会第30回大会のシンポジウム "Does Spelling Matter in Pre-Standardised Middle English?" を終えて」 ([2014-12-10-1])).

間違いなく英語のスペリングがよく分かるようになります.『スペリングの英語史』を是非ご一読ください.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ サイモン・ホロビン(著),堀田 隆一(訳) 『スペリングの英語史』 早川書房,2017年.

2017-09-21 Thu

■ #3069. 連載第9回「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」 [spelling][y][spelling_pronunciation_gap][minim][cawdrey][mulcaster][link][rensai][sobokunagimon][three-letter_rule]

昨日9月20日付けで,英語史連載企画「現代英語を英語史の視点から考える」の第9回の記事「なぜ try が tried となり,die が dying となるのか?」が公開されました.

本ブログでも綴字(と発音の乖離)の話題は様々に取りあげてきましたが,今回は標題の疑問を掲げつつ,言うなれば <y> の歴史とでもいうべきものになりました.書き残したことも多く,<y> の略史というべきものにとどまっていますが,とりわけ各時代における <i> との共存・競合の物語が読みどころです.ということは,部分的に <i> の略史ともなっているということです.標題の素朴な疑問を解消しつつ,英語の綴字の歴史のさらなる深みへと誘います.

本文の第3節で "minim avoidance" と呼ばれる中英語期の特異な綴字習慣を紹介していますが,これは英語の綴字に広範な影響を及ぼしており,本ブログでも以下の記事で触れてきました.連載記事を読んでから以下のそれぞれに目を通すと,おそらくいっそう興味をもたれることと思います.

・ 「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1])

・ 「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1])

・ 「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1])

・ 「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1])

・ 「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1])

・ 「#2740. word のたどった音変化」 ([2016-10-27-1])

・ 「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1])

・ 「#3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか?」 ([2017-08-20-1])

第4節では,リチャード・マルカスターの綴字提案とロバート・コードリーの英英辞書に触れました.1600年前後に活躍したこの2人の教育者については,「#441. Richard Mulcaster」 ([2010-07-12-1]) と「#603. 最初の英英辞書 A Table Alphabeticall (1)」 ([2010-12-21-1]) を始め,mulcaster と cawdrey の各記事もご参照ください.

最後に,第5節で「3文字」規則に触れましたが,こちらに関しては「#2235. 3文字規則」 ([2015-06-10-1]),「#2437. 3文字規則に屈したイギリス英語の <axe>」 ([2015-12-29-1]) の記事を読むことにより理解が深まると思います.

2017-09-02 Sat

■ #3050. rhubarb の綴字の運命 [spelling][etymological_respelling]

日本ではお目にかからないが,西洋で rhubarb /ˈruːbɑːb/ (ルバーブ)と呼ばれる食用植物がある.フキに似ているが,葉が赤みを帯びており,酸味を伴うためにジャムやソースの材料となる.

今回の話題は,この rhubarb の綴字が rubarb へ変化してきているらしいということだ.この語は,フランス語 reubarbe が中英語期に rubarbe として借用されたもので,当時は <rh> の綴字はなかった.もともとはラテン語,さらにはギリシア語に遡り,そこでは <rh> の綴字も見られたので,英語は近代期にそれを参照して rhubarb と綴りなおした(現代フランス語でも rhubarbe の綴字である).つまり,典型的な語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の例である.

このように,英語では rhubarb が標準的な綴字として定まったわけだが,近年,元に戻るかのような <h> を削除した rubarb が現われてきているという.Crystal (220--21) が,この綴字の変化に注目している.

I have been following the fate of the h in rhubarb in the Google database over the past few years. In 2006 there were just a few hundred instances of rubarb; in 2008 a few thousand; in 2010 there were 91,000; at the beginning of 2011 this had increased to 657,000, and by the end of the year it had passed a million. The ratios are the interesting thing: those 91,000 instances of rubarb in 2010 compared to 3,210,000 instances of rhubarb --- a ratio of 1:35. The following year, 657,000 rubarbs compared to 13 million rhubarbs --- a ratio of 1:20. And later that year rubarb passed the million mark. If it carries on like this, rubarb will overtake rhubarb as the commonest online spelling in the next five years. And where the online orthographic world goes in one decade, I suspect the offline world will go in the next.

rubarb の新綴字は「綴字間違い」にすぎないという向きもあるだろう.確かにスタートとしてはそうだったかもしれない.しかし,もしこの「綴字間違い」が進行し,オンラインで本来の rhubarb を抜く事態となったとすれば,もはや「綴字間違い」ではなく,少なくとも異綴字とみなされるようになるのではないか.私の手持ちの辞書では rubarb は,見出しはおろか異綴字としてすら掲載されておらず,現在「非標準」であることは疑いえないが,今後 r(h)ubarb にどのような運命が待ち構えているのか,気長に待っていきたい.

・ Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012.

2017-08-26 Sat

■ #3043. 後期近代英語期の識字率 [literacy][demography][spelling][lexicology]

過去の社会の識字率を得ることは一般に難しいが,後期近代英語期の英語社会について,ある程度分かっていることがある.以下にメモしておこう.

まず,Fairman (265) は,19世紀初期の状況として次の事実を指摘している.

1) In some parts of England 70% of the population could not write . . . . For them English was only sound, and not also marks on paper.

2) Of the one-third to 40% who could write, less than 5% could produce texts near enough to schooled English --- that is, to the type of English taught formally --- to have a chance of being printed.

Simon (160) は,19世紀中の識字率の激増,特に女性の値の増加について触れている.

The nineteenth century witnessed a huge increase in literacy, especially in the second half of the century. In 1850 30 per cent of men and 45 per cent of women were unable to sign their own names; by 1900 that figure had shrunk to just 1 per cent for both sexes.

上のような識字率と関連させて,Tieken-Boon van Ostade (45--46) がこの時代の綴字教育について論じている.貧しさゆえに就学期間が短く,中途半端な綴字教育しか受けられなかった子供たちは,せいぜい単音節語を綴れるにすぎなかっただろう.このことは,本来語はおよそ綴れるが,ほぼ多音節語からなるラテン語やフランス語からの借用語は綴れないことを意味する.文体レベルの高い借用語を自由に扱えないようでは社会的には無教養とみなされるのだから,彼らは書き言葉における「制限コード」 (restricted code) に甘んじざるをえなかったと表現してもよいだろう.

識字率,綴字教育,音節数,本来語と借用語,制限コード.これらは言語と社会の接点を示すキーワードである.

・ Fairman, Tony. "Letters of the English Labouring Classes and the English Language, 1800--34." Insights into Late Modern English. 2nd ed. Ed. Marina Dossena and Charles Jones. Bern: Peter Lang, 2007. 265--82.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-08-20 Sun

■ #3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか? [spelling][vowel][spelling][minim][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の綴字で feet, greet, meet, see, weed など <ee> は頻出するし,foot, look, mood, stood, took のように <oo> も普通に見られる.それに比べて,aardvark, bazaar, naan のような <aa> は稀だし,日常語彙で <ii>, <uu> もほとんど見られないといっていよい.長母音を表わすのに母音字を重ねるというのは,きわめて自然で普遍的な発想だと思われるが,なぜこのような偏った分布になっているのだろうか.

古英語では,短母音とそれを伸ばした長母音を区別して標示するのに特別は方法はなかった."God" と "good" に対応する語はともに god と綴られたし,witan は短い i で発音されれば "to know" の意味の語,長い i で発音されれば "to look" の意味の語となった.しかし,中英語になると,このような母音の長短の区別をつけようと,いくつかの方法が編み出された.それらの方法はおよそ現代英語に残っており,<ae>, <ei>, <eo>, <ie>, <oe> のように異なる複数の母音字を組み合わせるものもあれば,<a .. e>, <i .. e>, <u .. e> など遠隔的に組み合わせる方法もあったし,より直観的に,同じ母音字を重ねる <aa>, <ee>, <ii>, <oo>, <uu> などもあった.単語により,あるいはその単語のもっている発音により相当に込み入った事情があるなかで,徐々に典型的な綴り方が絞られていったが,同じ母音字を重ねる方式に関しては,<ee>, <oo> だけが残った.いったいなぜだろうか.

<ee> と <oo> が保持されやすい特殊な事情があったというよりは,むしろ <aa>, <ii>, <uu> が採用されにくい理由があったと考えるほうが妥当である.というのは上に述べたように,母音字を重ねるという方式はしごく自然と考えられ,それが採用されない理由を探るほうが容易に思われるからだ.

<ii> と <uu> が避けられたのは説明しやすい.中世においては,これらの綴字はいずれも点の付かない縦棒 (minim) のみで構成されており,それぞれ <ıı>, <ıııı> と綴られた.このように複数の縦棒が並列すると,意図されているのがどの文字(の組み合わせ)なのかが読み手にとって分かりにくくなるからだ.例えば,<ıııı> という綴字を見せられても,意図されているのが <iiii>, <ini>, <im>, <mi>, <nn>, <nu>, <un>, <wi> 等のいずれを表わすかは文脈を参照しなければわからない.関連して,「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]),「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]),「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]),「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1]),「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]),「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1]) を参照されたい.

<aa> については,なぜこれが採用されなかったのかの説明は難しい.初期中英語には,<aa> で綴られる単語もいくつかあったが,後世に伝わらなかった.Crystal (46) は,"aa never survived, probably because the 'silent' e spelling had more quickly established itself as the norm, as in name, tale, etc." と考えているが,もうそうだとしてももっと説得力のある説明が欲しいところだ.

結局,特に差し障りがなく自然なまま生き残ったのが <ee>, <oo> ということだ.関連して,「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1]) および「#2887. 連載第3回「なぜ英語は母音を表記するのが苦手なのか?」」 ([2017-03-23-1]) を参照

・ Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012.

2017-08-20 Sun

■ #3037. <ee>, <oo> はあるのに <aa>, <ii>, <uu> はないのはなぜか? [spelling][vowel][spelling][minim][sobokunagimon]

現代英語の綴字で feet, greet, meet, see, weed など <ee> は頻出するし,foot, look, mood, stood, took のように <oo> も普通に見られる.それに比べて,aardvark, bazaar, naan のような <aa> は稀だし,日常語彙で <ii>, <uu> もほとんど見られないといっていよい.長母音を表わすのに母音字を重ねるというのは,きわめて自然で普遍的な発想だと思われるが,なぜこのような偏った分布になっているのだろうか.

古英語では,短母音とそれを伸ばした長母音を区別して標示するのに特別は方法はなかった."God" と "good" に対応する語はともに god と綴られたし,witan は短い i で発音されれば "to know" の意味の語,長い i で発音されれば "to look" の意味の語となった.しかし,中英語になると,このような母音の長短の区別をつけようと,いくつかの方法が編み出された.それらの方法はおよそ現代英語に残っており,<ae>, <ei>, <eo>, <ie>, <oe> のように異なる複数の母音字を組み合わせるものもあれば,<a .. e>, <i .. e>, <u .. e> など遠隔的に組み合わせる方法もあったし,より直観的に,同じ母音字を重ねる <aa>, <ee>, <ii>, <oo>, <uu> などもあった.単語により,あるいはその単語のもっている発音により相当に込み入った事情があるなかで,徐々に典型的な綴り方が絞られていったが,同じ母音字を重ねる方式に関しては,<ee>, <oo> だけが残った.いったいなぜだろうか.

<ee> と <oo> が保持されやすい特殊な事情があったというよりは,むしろ <aa>, <ii>, <uu> が採用されにくい理由があったと考えるほうが妥当である.というのは上に述べたように,母音字を重ねるという方式はしごく自然と考えられ,それが採用されない理由を探るほうが容易に思われるからだ.

<ii> と <uu> が避けられたのは説明しやすい.中世においては,これらの綴字はいずれも点の付かない縦棒 (minim) のみで構成されており,それぞれ <ıı>, <ıııı> と綴られた.このように複数の縦棒が並列すると,意図されているのがどの文字(の組み合わせ)なのかが読み手にとって分かりにくくなるからだ.例えば,<ıııı> という綴字を見せられても,意図されているのが <iiii>, <ini>, <im>, <mi>, <nn>, <nu>, <un>, <wi> 等のいずれを表わすかは文脈を参照しなければわからない.関連して,「#91. なぜ一人称単数代名詞 I は大文字で書くか」 ([2009-07-27-1]),「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]),「#870. diacritical mark」 ([2011-09-14-1]),「#1094. <o> の綴字で /u/ の母音を表わす例」 ([2012-04-25-1]),「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]),「#2450. 中英語における <u> の <o> による代用」 ([2016-01-11-1]) を参照されたい.

<aa> については,なぜこれが採用されなかったのかの説明は難しい.初期中英語には,<aa> で綴られる単語もいくつかあったが,後世に伝わらなかった.Crystal (46) は,"aa never survived, probably because the 'silent' e spelling had more quickly established itself as the norm, as in name, tale, etc." と考えているが,もうそうだとしてももっと説得力のある説明が欲しいところだ.

結局,特に差し障りがなく自然なまま生き残ったのが <ee>, <oo> ということだ.関連して,「#2092. アルファベットは母音を直接表わすのが苦手」 ([2015-01-18-1]) および「#2887. 連載第3回「なぜ英語は母音を表記するのが苦手なのか?」」 ([2017-03-23-1]) を参照

・ Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Singular Story of English Spelling. London: Profile Books, 2012.

2017-08-05 Sat

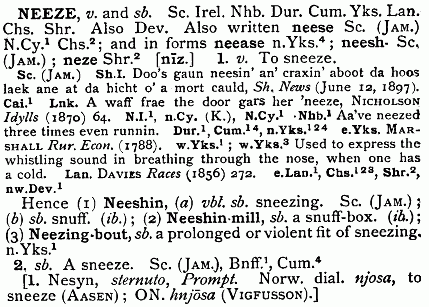

■ #3022. sneeze の語源 (2) [spelling][onomatopoeia][edd][etymology]

「#1152. sneeze の語源」 ([2012-06-22-1]) を巡る議論に関連して,追加的に話題を提供したい.Horobin (60) は,この問題について次のように評している.

. . . Old English had a number of words that began with the consonant cluster <fn>, pronounced with initial /fn/. This combination is no longer found at the beginning of any Modern English word. What has happened to these words? In the case of the verb fneosan, the initial /f/ ceased to be pronounced in the Middle English period, giving an alternative spelling nese, alongside fnese. Because it was no longer pronounced, the <f> began to be confused with the long-s of medieval handwriting and this gave rise to the modern form sneeze, which ultimately replaced fnese entirely. The OED suggests that sneeze may have replaced fnese because of its 'phonetic appropriateness', that is to say, because it was felt to resemble the sound of sneezing more closely. This is a tempting theory, but one that is hard to substantiate.

また,現代でも諸方言には,語頭に摩擦子音のみられない neese や neeze の形態が残っていることに注意したい.EDD Online の NEEZE, v. sb. によれば,以下の通り neese, neease, neesh-, neze などの異綴字が確認される.

long <s> については,「#584. long <s> と graphemics」 ([2010-12-02-1]),「#1732. Shakespeare の綴り方 (2)」 ([2014-01-23-1]),「#2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s>」 ([2017-07-11-1]) を参照.

・ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter? Oxford: OUP, 2013.

2017-07-30 Sun

■ #3016. colonel の綴字と発音 [spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap][dissimilation][silent_letter][folk_etymology][l][r]

(陸軍)大佐を意味する colonel は,この綴字で /ˈkəːnəl/ と発音される.別の単語 kernel (核心)と同じ発音である.l が黙字 (silent_letter) であるばかりか,その前後の母音字も,発音との対応があるのかないのかわからないほどに不規則である.これはなぜだろうか.

この単語の英語での初出は1548年のことであり,そのときの綴字は coronell だった.l ではなく r が現われていたのである.これは対応するフランス語からの借用語で,そちらで coronnel, coronel, couronnel などと綴られていたものが,およそそのまま英語に入ってきたことになる.このフランス単語自体はイタリア語からの借用で,イタリア語では colonnello, colonello のように綴られていた.つまり,イタリア語からフランス語へ渡ったときに,最初の流音が元来の l から r へすり替えられたのである.これはロマンス諸語ではよくある異化 (dissimilation) の作用の結果である (cf. Sp. coronel) .語中に l 音が2度現われることを嫌っての音変化だ(英語に関する類例は「#72. /r/ と /l/ は間違えて当然!?」 ([2009-07-09-1]),「#1597. star と stella」 ([2013-09-10-1]),「#1614. 英語 title に対してフランス語 titre であるのはなぜか?」 ([2013-09-27-1]) を参照).

さらに語源を遡ればラテン語 columnam (円柱)に行き着き,「兵士たちの柱(リーダー)」ほどの意味で用いられるようになった.フランス語で変化した coronnel の綴字についていえば,民間語源 (folk_etymology) により corona, couronne "crown" と関係づけられて保たれた.しかし,フランス語でも16世紀後半には l が綴字に戻され,colonnel として現在に至る.

英語では,当初の綴字に基づき l ではなく r をもつ発音がその後も用いられ続けたが,綴字に関しては早くも16世紀後半に元来の綴字を参照して l が戻されることになった.フランス語における l の復活も同時に参照したものと思われる.18世紀前半までは古い coronel も存続していたが,徐々に消えていき現在の colonel が唯一の綴字となった.発音は古いものに据えおかれ,綴字だけが変化したがゆえに,現在にまで続く綴字と発音のギャップが生じてしまったというわけだ.

しかし,実際の経緯は,上の段落で述べたほど単純ではなかったようだ.綴字に l が戻されたのに呼応して発音でも l が戻されたと確認される例はあり,/ˌkɔləˈnɛl/ などの発音が19世紀初めまで用いられていたという.発音される音節数についても通時的に変化がみられ,本来は3音節語だったが17世紀半ばより2音節語として発音される例が現われ,19世紀の入り口までにはそれが一般化しつつあった.

<colonel> = /ˈkəːnəl/ は,綴字と発音の関係が複雑な歴史を経て,結果的に不規則に固まってきた数々の事例の1つである.

2017-07-12 Wed

■ #2998. 18世紀まで印刷と手書きの綴字は異なる世界にあった [spelling][orthography][writing][printing][lmode][johnson]

昨日の記事「#2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s>」 ([2017-07-11-1]) の最後に触れたように,十分に現代英語に近いと感じられる18世紀でも(そして部分的に19世紀ですら),印刷と手書きは,文字や綴字の規範に関して,2つの異なる世界を構成していたといってよい.換言すれば,2つの正書法が存在していた(しかも,各々は現代的な意味での水も漏らさぬ強固な規範というわけではなかった).印刷はおよそ「公」であり,手書きは「私」であるから,正書法は公私で使い分けるべき二重基準となっていたのである.

この差異が最も印象的に見られるのは,Johnson の辞書での綴字と,Johnson の私的書簡での綴字である.例えば,Johnson は辞書での綴字とは異なり,書簡では companiable, enervaiting, Fryday, obviateing, occurences, peny, pouns, stiched, chappel, diner, dos (= does) 等の綴字を書いている (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 42) .このような状況は他の作家についても同様に見られることから,Johnson が綴り下手だったとか,自己矛盾を起こしているなどという結論にはならない.むしろ,公的な印刷と私的な手書きとで異なる綴字の基準があり,それが当然視されていた,ということである.

このような状況は,現代の我々にとっては理解しにくいかもしれないが,当時の綴字教育の現状を考えてみれば自然のことである.後期近代英語期には綴字の教科書は多く出版されたが,それは子供たちに印刷されたテキストを読めるようにするための教科書であり,子供たちが自ら綴字を書くことを訓練する教科書ではなかった.印刷テキストの綴字は,印刷業者によって慣習的に定められた正書法が反映されており,子供たちはその体系的な綴字を「読む」訓練こそ受けたが,「書く」訓練は特に受けていなかった.そのような子供たちが手書きで書簡を認める段には,当然ながら印刷テキストに表わされている正書法に則って綴ることはできない.しかし,だからといって単語をまったく綴れないということにはならないし,書簡の受け手に誤解されることもほとんどないだろう.

そして,この状況は,綴字を学んでいる子供たちのみならず,文字を読み書きする大人たちにも一般に当てはまった.印刷と手書きの対立は,公私の対立のみならず,綴字を読む能力と書く能力の対立でもあったのだ.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-07-11 Tue

■ #2997. 1800年を境に印刷から消えた long <s> [spelling][graphemics][grammatology][alphabet][printing][lmode][writing][orthography]

18世紀の印刷本のテキストを読んでいると,中世から続く <s> の異字体 (allograph) である <<ʃ>> がいまだ頻繁に現われることに気づく.この字体は "long <s>" と呼ばれており,現代までに廃れてしまったものの,英語史の長きにわたって活躍してきた異字体だった.Tieken-Boon van Ostade (40) に引かれている ECCO からの例文により,<<ʃ>> の使われ方を見てみよう.

. . . WHEREIN / THE CHAPTERS are ʃumm'd up in Contents; the Sacred Text inʃerted at large, in Paragraphs, or Verʃes; and each Paragraph, or Verʃe, reduc'd to its proper Heads; the Senʃe given, and largely illuʃtrated, / WITH / Practical Remarks and Obʃervations

見てわかる通り,すべての <s> が <<ʃ>> で印刷されているわけではない.基本的には語頭か語中の <s> が <<ʃ>> で印刷され,語末では通常の <<s>> しか現われない.また,語頭でも大文字の場合には <<S>> が用いられる.ほかに,Idleneʃs や Busineʃs のように,<ss> の環境では1文字目が long <s> となる.

しかし,この long <s> もやがて廃用に帰することとなった.印刷においては18世紀末に消えていったことが指摘されている.

Long <s> disappeared as a printing device towards the end of the eighteenth century, and its presence or absence is today used by antiquarians to date books that lack a publication date as dating from either before or after 1800. (Tieken-Boon van Ostade 40)

注意すべきは,1800年を境に long <s> が消えたのは印刷という媒体においてであり,手書き (handwriting) においては,もうしばらく long <s> が使用され続けたということである.「#584. long <s> と graphemics」 ([2010-12-02-1]) で触れたように,手書きでは1850年代まで使われ続けた.印刷と手書きとで使用分布が異なっていたことは long <s> に限らず,他の異字体や異綴字にも当てはまる.現代の感覚では,印刷にせよ手書きにせよ,1つの共通した正書法があると考えるのが当然だが,少なくとも1800年頃までは,そのような感覚は稀薄だったとみなすべきである.

long <s> について,「#1152. sneeze の語源」 ([2012-06-22-1]),「#1732. Shakespeare の綴り方 (2)」 ([2014-01-23-1]) も参照されたい.

・ Tieken-Boon van Ostade, Ingrid. An Introduction to Late Modern English. Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 2009.

2017-05-18 Thu

■ #2943. 英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由は「見栄」と「惰性」? [notice][spelling][spelling_pronunciation_gap][etymological_respelling][link]

先日,「英語の発音と綴字の乖離」の問題について,DMM英会話ブログさんにインタビューしていただき,記事にしてもらいました.昨日その記事がアップロードされたので,今日はそれを紹介がてら,関連する hellog 記事へのリンクを張っておきます.記事のタイトルは,ずばり「圧倒的腹落ち感!英語の発音と綴りが一致しない理由を専門家に聞きに行ったら,犯人は中世から近代にかけての「見栄」と「惰性」だった.」です.こちらからどうぞ.

最大限に分かりやすい解説を目指し,話しをとことんまで簡略化しました.簡略化するあまり,細かな点では不正確,あるいは言葉足らずなところもあると思いますが,多くの英語学習者の方々に関心をもたれる話題に対して,英語史の観点からどのように迫れるのか,英語史的な見方の入り口を垣間見てもらえるように,との思いからです.趣旨を汲み取ってもらえればと思います.かる?く,ゆる?く読んで「腹落ち感」を味わってください.

さて,本ブログでは「英語の発音と綴字の乖離」問題について,spelling_pronunciation_gap の多くの記事で論じてきました.今回のインタビュー記事では,debt になぜ発音しない <b> があるのか,といった語源的綴字 (etymological_respelling) の話題を主として取り上げました.インタビュー中に言及のある具体的な事例との関係では,特に以下の記事をご覧ください.

・ debt の <b> の謎:「#116. 語源かぶれの綴り字 --- etymological respelling」 ([2009-08-21-1])

・ 中英語の through の綴字に見られる混乱:「#53. 後期中英語期の through の綴りは515通り」 ([2009-06-20-1])

・ 15世紀の through の綴字の収束:「#193. 15世紀 Chancery Standard の through の異綴りは14通り」 ([2009-11-06-1])

・ 発音と綴字が別々に走っていた件:「#2292. 綴字と発音はロープでつながれた2艘のボート」 ([2015-08-06-1])

・ 不規則性・不合理性を保つことに意味がある!?:「#1482. なぜ go の過去形が went になるか (2)」 ([2013-05-18-1])

1時間ほどのインタビューで上手に話し尽くせるようなテーマではありませんでしたが,読者のみなさんがこの問題に,また英語史という分野に関心を抱く機会となれば,私としては目的達成です.

2017-04-18 Tue

■ #2913. 漢字は Chinese character ではなく Chinese spelling と呼ぶべき? [grammatology][kanji][alphabet][word][writing][spelling]

高島 (43) による漢字論を読んでいて,漢字という表語文字の一つひとつは,英語などでいうところの綴字に相当するという点で,Chinese character ではなく Chinese spelling と呼ぶ方が適切である,という目の覚めるような指摘にうならされた.

漢字というのは,その一つ一つの字が,日本語の「い」とか「ろ」とか,あるいは英語の a とか b とかの字に相当するのではない.漢字の一つ一つの字は,英語の一つ一つの「つづり」(スペリング)に相当するのである.「日」は sun もしくは day に,「月」は moon もしくは month に相当する.英語の一つ一つの単語がそれぞれ独自のつづりを持つように,漢語の一つ一つの単語はそれぞれ独自の文字を持つのである.であるからして,漢字のことを英語で Chinese characters (シナ語の文字)と言うけれど,むしろ Chinese spellings (シナ語のつづり)と考えたほうがよい.

ときどき,英語のアルファベットはたったの二十六字で,それで何でも書けるのに,漢字は何千もあるからむずかしい,と言う人があるが,こういうことを言う人はかならずバカである.漢字の「日」は sun や day にあたる.「月」は moon や month にあたる.この sun だの moon だののつづりは,やはり一つ一つおぼえるほかない.知れきったことである.漢語で通常もちいられる字は三千から五千くらいである.英語でも通常もちいられる単語の数は三千から五千くらいである.おなじくらいなのである.それで一つ一つの漢字があらわしているのは一つの意味を持つ一つの音節であり,「日」にせよ「月」にせよその音は一つだけなのだから,むしろ英語のスペリングよりやさしいかもしれない.

確かに,この見解は多くの点で優れている.アルファベットの <a>, <b>, <c> 等の各文字は,漢字でいえば言偏や草冠やしんにょう等の部首(あるいはそれより小さな部品や一画)に相当し,それらが適切な方法で組み合わされることによって,初めてその言語の使用者にとって最も基本的で有意味な単位と感じられる「語」となる.「語」という単位にまでもっていくための部品統合の手続きを「綴り」と呼ぶとすれば,確かに <sun> も <sunshine> も <日> も <陽> もいずれも「綴り」である.アルファベットにしても漢字にしても,当面の目標は「語」という単位を表わすことである点で共通しているのだから,概念や用語も統一することが可能である.

文字の最重要の機能の1つが表語機能 (logographic function) であることは,すでに本ブログの多くの箇所で述べてきたが(例えば,以下の記事を参照),英語の綴字と漢字が機能的な観点から同一視できるという高島の発想は,改めて文字表記の表語性の原則をサポートしてくれるもののように思われる.

・ 「#284. 英語の綴字と漢字の共通点」 ([2010-02-05-1])

・ 「#285. 英語の綴字と漢字の共通点 (2)」 ([2010-02-06-1])

・ 「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1])

・ 「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1])

・ 「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1])

・ 「#2344. 表意文字,表語文字,表音文字」 ([2015-09-27-1])

・ 「#2389. 文字体系の起源と発達 (1)」 ([2015-11-11-1])

・ 「#2429. アルファベットの卓越性という言説」 ([2015-12-21-1])

・ 高島 俊男 『漢字と日本人』 文藝春秋社,2001年.

2017-03-27 Mon

■ #2891. フランス語 bleu に対して英語 blue なのはなぜか [yod-dropping][vowel][spelling][french][mulcaster][sobokunagimon]

3月17日付の掲示板で,フランス語の bleu という綴字に対して,英語では blue となっているのはなぜか,という質問が寄せられた.e と u の転換がどのように起こったか,という疑問である.

これには少々ややこしい歴史的経緯がある.古フランス語の bleu が中英語期にこの綴字で英語に借用され,後に2字の位置が交替して blue となった,という直線的な説明で済むものではないようだ.以下,発音と綴字を分けて歴史を追ってみよう.

まず,発音から.問題の母音の中英語での発音は [iʊ] に近かったと想定されるが,これが初期近代英語にかけて強勢推移により上昇2重母音 [juː] となり,さらに現代にかけて yod-dropping が生じて [uː] となった(「#1727. /ju:/ の起源」 ([2014-01-18-1]),「#841. yod-dropping」 ([2011-08-16-1]),「#1562. 韻律音韻論からみる yod-dropping」 ([2013-08-06-1]) を参照).

次に,ややこしい綴字の事情について.まず,この語は中英語では,当然ながら借用元のフランス語での綴字にならって bleu と綴られていた.しかし,実際のところ,<blew>, <blewe> などの異綴字として現われていることも多かった(MED bleu (adj.) を参照.関連して,「#2227. なぜ <u> で終わる単語がないのか」 ([2015-06-02-1]) も参照)).一方,現代的な blue という綴字として現われることは,中英語期中はもとより17世紀まで稀だった.Jespersen (101) が,この点に少し触れている.

In blue /iu/ is from F eu; in ME generally spelt bleu or blew; the spelling blue is "hardly known in 16th--17th c.; it became common under French influence (?) only after 1700" (NED)

引用にもある通り,中英語では bleu と並んで blew の綴字もごく一般的だった.実際,[iʊ] の発音に対しては,フランス借用語のみならず本来語であっても,<ew> で綴られることが多かった.例えば vertew (< OF vertu), clew (< OE cleowen), trew (< OE trēowe), Tewisday (< OE Tīwesdæȝ) のごとくである.

しかし,初期近代英語期にかけて,同じ [iʊ] の発音に対して <ue> というライバル綴字が現われてきた.この綴字自体はフランス語やラテン語に由来するものだったが,いったんはやり出すと,語源にかかわらず多くの単語に適用されるようになった.つまり,同じ [iʊ] に対して,より古くて英語らしい <ew> と,より新しくてフランス語風味の <ue> が競合するようになったのである.その結果,近代英語では argue/argew, dew/due, screw/skrue, sue/sew, virtue/virtew などの揺れが多く見られた(各ペアにおいて前者が現代の標準的綴字).そして,blue/blew もそのような揺れを示すペアの1つだったのである.

このような揺れが,後にいずれの方向で解消したのかは単語によって異なっており,およそ恣意的であるとしか言いようがない.初期近代英語期に <ew> を贔屓する Mulcaster のような論者もいたが,それが一般に適用される規則として発展することはなかったのである.現代の正書法において blew ではなく blue であること,eschue ではなく eschew であることは,きれいに説明することはできない.

さて,もともとの疑問に戻ってみよう.当初の問題意識としては,現代のフランス語と英語を比べる限り,<eu> と <ue> が文字転換したように見えただろう.しかし,歴史的には,<eu> の文字がひっくり返って <ue> となったわけではない.<eu> と関連していたとは思われるが中英語期に独自に発達したとみなすべき英語的な <ew> と,初期近代英語期にかけて勢力を伸ばしてきた外来の <ue> との対立が,blue という単語に関する限り,たまたま後者の方向で解消し,標準化して現代に至る,ということである.

以上,Upward and Davidson (61--62, 113, 161, 163, 166) を参照した.

・ Jespersen, Otto. A Modern English Grammar on Historical Principles. Part 1. Sounds and Spellings. 1954. London: Routledge, 2007.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

2017-03-15 Wed

■ #2879. comfort の m の由来 [suffix][spelling]

昨日の記事「#2878. comfort の m の発音」 ([2017-03-14-1]) に引き続き,掲示板で寄せられた質問について.ラテン語接頭辞 com- は,後続する形態素の先頭が f の場合には,通常 con- に変化するはずではないか,という問題である.確かに conference, confident, configuration, confine 等々,ほとんどのケースで con- となっている.しかし,comfort(table) は例外となり,その他の例外も comfort に関連する語か,comfit (糖果),comfiture (糖果),comfrey (コンフリー,ムラサキ科ヒレハリソウ属の多年草)くらいのもので,非常に稀である.

改めて接頭辞の語源について整理しておこう.原型たる com- はラテン語で "with, together" を意味する語 cum が接頭辞として用いられるようになったもので,ラテン語から直接,またフランス語から間接的に英語に入った.具体的な語のなかでは,末尾の m は音声上の同化により様々な現れ方を示す.通常は,b, p, m などの前では com- がそのまま現れるが,l の前では col- として,r の前では cor- として,母音および h, gn, w の前では co- として現れ,それ以外の場合には con- となる.しかし,例外は多く,comfort もその1つである.

Upward and Davidson (142) は,この辺りのことを以下のように解説しているが,comfort や comfit については単に例外的と指摘しているのみで,その原因については述べていない.

Before B and P, OFr normally wrote CUM-: cumbatre 'to combat', cumpagnie 'company'. Although this was later altered back to the Lat COM- spelling, Eng retained the pronunciation related to CUM-, whence the /ʌ/ vowel of comfort, company, compass, etc.

In comfort and comfit, the CON- was altered in Eng to COM-: comfort < OFr cunforter < Lat confortare 'to strengthen'; comfit < ME confyt < OFr confit.

さらに,comfort について Barnhart の語源辞典に当たってみると,古フランス語からの借用に関連してややこしい事情があるようで,綴字に関しても当初は con- だったが,後に英語側で com- へと変化したという指摘がある.

Probably before 1200 cunfort a feeling of consolation, in Ancrene Riwle; later confort (about 1200 and about 1280); borrowed probably through Anglo-French from Old French cunfort, confort, from earlier noun use derived from the stem of Latin cōnfortāre strengthen. Apparently the noun and verb were borrowed separately in English, though the noun replaced earlier Old English frōfor; however, it is possible that the later verb is from the noun. The phonetic change of con- to com- before f took place in English.

Skeat の語源辞典でも,やはり英語において con- から com- へ変化したという事実しか記載されていない.

Though the verb is the original of the sb., the latter seems to have been earlier introduced into English. The ME. verb is conforten, later comforten, by the change of n to m before f. It is used by Chaucer, Troil. and Cress. iv. 722, v. 234, 1395. [The sb. confort is in Chaucer, Prol. 775, 7788 (A 773, 776); but occurs much earlier. It is spelt cunfort in Ol Eng. Homilies, ed. Morris, i. 185; kunfort in Ancren Riwle, p. 14.]

中英語での異綴字の分布や古フランス語での綴字を詳しく調査してみない限り,comfort の m の「なぜ?」には,これ以上迫ることはできなさそうである.

なお,comfit の綴字については,『シップリー英語語源辞典』の confectionery の項に,意味的に comfort と緩やかに関連づけられたのではないかとの指摘がある.

・ Upward, Christopher and George Davidson. The History of English Spelling. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011.

・ Barnhart, Robert K. and Sol Steimetz, eds. The Barnhart Dictionary of Etymology. Bronxville, NY: The H. W. Wilson, 1988.

・ ジョーゼフ T. シップリー 著,梅田 修・眞方 忠道・穴吹 章子 訳 『シップリー英語語源辞典』 大修館,2009年.

2017-01-29 Sun

■ #2834. wimmin と herstory [political_correctness][pronunciation_spelling][spelling][pronunciation][spelling_pronunciation_gap]

標題の最初の語は woman の複数形 women を表わす PC 的な綴字である.従来の標準的な綴字では,woman/women が man/men からの派生であり,したがって副次的であるという含意を伴うために,それを改善すべくフェミニストが表音的な綴字を作り出したという経緯があった.現在でも主要な英和辞典には見出し語として挙がっているが,ほとんどの英英辞典では見出しが立てられていない.落ちぶれた一時限りの流行語,という扱いなのだろう.今では,歴史的な価値しか残っていない.

同様に,history に対する herstory も,PC 史ではことのほかよく知られている.「フェミニストの観点からの歴史,女性の歴史」を指すが,やはり現在の英英辞典では扱われていない.

Hughes (183) が,これらの語の歴史に関して解説を加えている.両語とも,すっかりこけにされてしまったものである.

Wimmin . . . attracted a lot of publicity in 1982--3 before going through the phases of satire and obsolescence prior to fading away. A similar feminist coinage was herstory, briefly institutionalized in the acronym "WITCH --- Women Inspired to Commit Herstory," in Robin Morgan's Sisterhood is Powerful (1970, p. 551). Jane Mills made this telling observation in her compendium Womanwords: "The rewriting or respeaking of history as herstory --- coined by some feminists in the 1970s --- is guaranteed to annoy most men, many women and almost all linguists" (1989, p. 118). Although the currency of herstory has declined, Elaine Showalter showed further creativity in her study Hystories: Hysterical Epidemics and the Modern Media (1997).

wimmin について,PC 史の観点からは,上の引用に述べられているほかに言うべきことはないが,綴字の問題と関連して,もう少し議論を続けてみたい.この綴字改革(あるいは綴字操作?)の背景にある考え方は,冒頭に述べたように,<women> という綴字は否応なしに <men> を連想させてしまう.視覚的に韻を踏んでいる (eye rhyme) からである.両語の形態・意味的なつながりは,無視し得ないほどに明白である.

ところが,発音は別の話だ.発音としては,むしろ /mɛn/ と /ˈwɪmɪn/ で韻を踏まない.つまり,発音を忠実に標記するような綴字に変えれば,両語の関係を見えにくくすることができる,ということになる.発音と綴字の乖離 (spelling_pronunciation_gap) は英語における悪名高い特徴だが,<wimmin> はまさにその特徴を逆手に取った pronunciation_spelling の技法の成果なのである.

現代英語の綴字体系の基本方針が,表音性 (phonography) というよりも表形態素性 (morphography) にあることは,「#1332. 中英語と近代英語の綴字体系の本質的な差」 ([2012-12-19-1]),「#1386. 近代英語以降に確立してきた標準綴字体系の特徴」 ([2013-02-11-1]),「#2043. 英語綴字の表「形態素」性」 ([2014-11-30-1]) などで見てきた通りである.端的にいえば,綴字は音より意味を表わすほうに重点を置くという方針だ.<wimmin> への綴字改革は,その裏をかいて,men との意味の連想を断つのに,その対立項としての表音重視をもってする,という戦略をとったことになる.綴字の担いうる表音機能と表形態素機能という文字論上の対立を,PC という社会言語学的な目的のために利用した例といえるだろう.綴字の政治利用の1形態と言ってもよい.PC がいかなる言語的な素材を戦略的に用いてきたか,その類型論を考える際に,<wimmin> はおもしろい例を提供してくれている.

women の発音と綴字を巡る話題については,「#223. woman の発音と綴字」 ([2009-12-06-1]),「#224. women の発音と綴字 (2)」 ([2009-12-07-1]),「#246. 男性着は「メンズ」だが,女性着は?」 ([2009-12-29-1]),「#247. 「ウィメンズ」と female」 ([2009-12-30-1]) も参照.

・ Hughes, Geoffrey. Political Correctness: A History of Semantics and Culture. Malden, ML: Wiley Blackwell, 2010.

2016-12-23 Fri

■ #2797. floccinaucinihilipilification [spelling][word_formation][latin][neo-latin][lexicology][phonaesthesia][sound_symbolism]

最長の英単語について,「#63. 塵肺症は英語で最も重い病気?」 ([2009-06-30-1]),「#391. antidisestablishmentarianism 「反国教会廃止主義」」 ([2010-05-23-1]),「#392. antidisestablishmentarianism にみる英語のロマンス語化」 ([2010-05-24-1]) の記事で論じてきた.もう1つ,おどけた表現として用いられる標題の単語 floccinaucinihilipilification を知った.『ランダムハウス英語辞典』では「英語で最も長い単語の例として引き合いに出される」とある.

OED の定義によると,"humorous. The action or habit of estimating as worthless." とある.「無価値とみなすこと,軽視癖」の意である.

語源・形態的に解説すると,ラテン語 floccus は「羊毛のふさ」,naucum は「取るに足りないもの」,nihil は「無」,pilus は「一本の毛」を意味し,これらの「つまらないもの」の束に,他動詞を作る facere を付加して,それをさらに名詞化した語である.ラテン語の語形成規則に則って正しく作られている語だが,あくまで英語の内部での造語であるという点では,一種の英製羅語である(関連して「#1493. 和製英語ならぬ英製羅語」 ([2013-05-29-1]) も参照).

OED によると,初出は1741年.以下に,2つほど例文を引用しよう.

1741 W. Shenstone Let. xxii, in Wks. (1777) III. 49, I loved him for nothing so much as his flocci-nauci-nihili-pili-fication of money.

1829 Scott Jrnl. 18 Mar. (1946) 39 They must be taken with an air of contempt, a floccipaucinihilipilification [sic, here and in two other places] of all that can gratify the outward man.

なお,発音は /ˌflɒksɪnɔːsɪˌnɪhɪlɪˌpɪlɪfɪˈkeɪʃən/ となっている.12音節,27音素からなる長大な1単語である.12の母音音素のうち,8個までが前舌後母音 /ɪ/ であるということは,「#242. phonaesthesia と 遠近大小」 ([2009-12-25-1]) で論じた phonaesthesia を思い起こさせる.小さいもの,すなわち無価値なものは,音象徴の観点からは前舌後母音と相性がよい,ということかもしれない.

Powered by WinChalow1.0rc4 based on chalow