英語史における借用語の最たる話題として,中英語期におけるフランス語彙の著しい流入が挙げられる.この話題に関しては,語彙統計の観点からだけでも,「#117. フランス借用語の年代別分布」 ([2009-08-22-1]) を始めとして,french loan_word statistics のいくつかの記事で取り上げてきた.しかし,語彙統計ということでいえば,近代英語期のラテン借用語を核とする語彙増加のほうが記録的である.

[2009-08-19-1]の記事「#114. 初期近代英語の借用語の起源と割合」で言及したが,Görlach は初期近代英語の語彙の著しい増大を次のように評価し,説明している.

The EModE period (especially 1530--1660) exhibits the fastest growth of the vocabulary in the history of the English language, in absolute figures as well as in proportion to the total. (136)

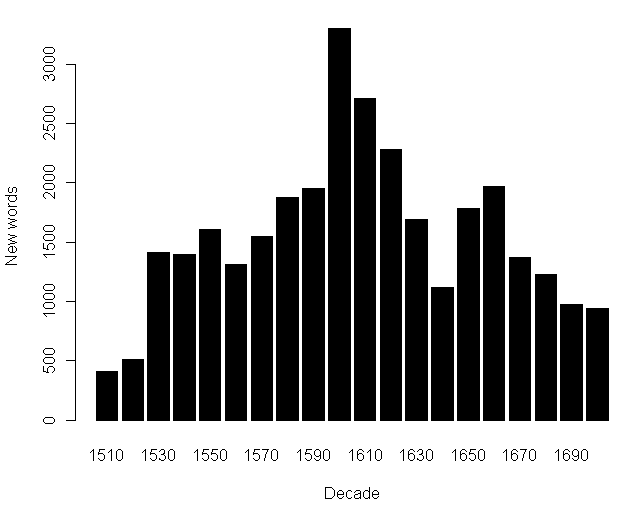

. . . the general tendencies of development are quite obvious: an extremely rapid increase in new words especially between 1570 and 1630 was followed by a low during the Restoration and Augustan periods (in particular 1680--1780). The sixteenth-century increase was caused by two factors: the objective need to express new ideas in English (mainly in fields that had been reserved to, or dominated by, Latin) and, especially from 1570, the subjective desire to enrich the rhetorical potential of the vernacular. / Since there were no dictionaries or academics to curb the number of new words, an atmosphere favouring linguistic experiments led to redundant production, often on the basis of competing derivation patterns. This proliferation was not cut back until the late seventeenth/eighteenth centuries, as a consequence of natural selection or a s a result of grammarians' or lexicographers' prescriptivism. (137--38)

Görlach は,A Chronological English Dictionary に基づいて,次のような語彙統計も与えている (137) .これを図示してみよう.

| Decade | 1510 | 1520 | 1530 | 1540 | 1550 | 1560 | 1570 | 1580 | 1590 | 1600 | 1610 | 1620 | 1630 | 1640 | 1650 | 1660 | 1670 | 1680 | 1690 | 1700 |

| New words | 409 | 508 | 1415 | 1400 | 1609 | 1310 | 1548 | 1876 | 1951 | 3300 | 2710 | 2281 | 1688 | 1122 | 1786 | 1973 | 1370 | 1228 | 974 | 943 |

近代英語期のラテン借用について関連する話題は,「#203. 1500--1900年における英語語彙の増加」 ([2009-11-16-1]) や emode loan_word lexicology の各記事を参照.

・ Görlach, Manfred. Introduction to Early Modern English. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

・ Finkenstaedt, T., E. Leisi, and D. Wolff, eds. A Chronological English Dictionary. Heidelberg: Winter, 1970.